Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Vanderbilt Audiology Journal Club: Cognition and Self-Efficacy, presented by Todd Ricketts, PhD; Erin Margaret Picou, AuD, PhD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- List new key journal articles on the topic of hearing aids that have implications for audiology clinical practice.

- Describe the purpose, methods, and results of new key journal articles on hearing aids that have implications for audiology practice.

- Explain some clinical takeaway points from new key journal articles on hearing aids.

Introduction

We are going to review the hearing aid research articles that have been published in the last year. We read all of the hearing aid-related papers in the last year. We then chose the papers that addressed two separate but related themes of self-efficacy and cognition.

The Relationship Between Hearing Loss Self-Management and Hearing Aid Benefit and Satisfaction (Convery, Keidser, Hickson, & Meyer, 2019)

This first paper was written by a group out of Australia. It was published in 2019 in the American Journal of Audiology.

What They Asked

The question they asked in the paper was, “Is there a relationship between self-reported hearing loss self-management and hearing aid benefit and satisfaction – among a group of experienced bilateral hearing aid users?”

A Little Background

The ability to self-manage a chronic condition like hearing loss is a factor that influences a person’s experience with that condition. The definition of self-management is “the knowledge and skills that are used to manage the effects of a chronic condition on all aspects of daily life.” Here are some skills that apply to self-management:

- Use and management of prescribed interventions.

- Maintaining physical and emotional well-being.

- Monitoring for and responding to changes in condition severity and functional status.

- Seeking out information, resources, and support.

- Taking an active role in clinical decision making.

When we think about hearing healthcare, some of those skills apply, and some do not. However, self-management in hearing healthcare can be about three things. The first is knowing about one’s condition. This includes the factors that caused the hearing loss. The second one is knowing about treatment options and management strategies. This refers to the options that are available for the degree, type, and configuration of the hearing loss. It is essential to also consider how an individual interacts with their environment to optimize their hearing abilities. The third one is managing the social and emotional effects of the condition during everyday life. This refers to how well an individual is coping with their hearing loss on an emotional and social level.

Why It Matters

In general, we know that self-management is linked to treatment outcomes. Here are some affected factors:

- Glycemic control and blood pressure.

- Day-to-day demands of chronic condition.

- Self-reported health distress.

- Greater feelings of empowerment, hopefulness, and motivation.

- Better self-reported general health.

If this is true, the authors of the paper wanted to know if self-management of hearing loss is related to outcomes with hearing aids.

What They Did

The authors evaluated the relationship between self-management and hearing aid benefit and satisfaction. They did this by using the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit. This is a 24-item questionnaire in which respondents rate the degree of difficulty they experience during everyday listening situations. It has four subscales, and the questions are related to the ease of communication, the difficulty of listening with background noise, reverberation, and the degree to which sounds are aversive. To measure hearing aid satisfaction, the authors used the Satisfaction with Amplification in Daily Life. This is a 15-item questionnaire that also has four subscales. They relate to the positive effects of the hearing aid, service and cost, negative features, and personal image. To evaluate self-management, they used a questionnaire paired with an interview. The respondent rates their ability to self-manage their hearing loss. An interviewer then follows up on each item with some questions and rates the respondent’s ability to self-manage. During this process, they used the Partners in Health Scale and the Cue and Response questionnaire.

When the authors completed factor analysis, they found that the Partners in Health Scale questions lumped into three main domains, which are knowledge, actions, and psychological behaviors. Knowledge refers to how well somebody knows their hearing loss and the appropriate treatments there are for that hearing loss. For example, a person would rate how much they know about their hearing loss, and a follow-up question in the Cue and Response would be, “What do you know about your hearing loss?”

With actions, this includes attending appointments, adhering to recommendations and treatments, self-management in the decision-making process with the clinician, and monitoring and addressing changes. For example, a rating could be about attending appointments as asked by a hearing healthcare professional. An interview cue would then be, “Is there anything that prevents you from attending appointments?”

The third domain is psychosocial behaviors. This refers to how well somebody is coping with emotional well-being and social participation. On the Partners in Health Scale, an example could be, “I manage the effect of my hearing loss and how I feel.” The interviewer would then follow up with, “Does your hearing loss ever get you down?” Higher scores would be indicative of better coping and more self-management with hearing loss.

The authors recruited 37 adults who were between the ages of 52 and 83 and have bilateral, longstanding hearing loss. They were all existing behind-the-ear (BTE) hearing aid users. All of them wore their hearing aids for more than four hours a day, and most of them wore it for more than eight hours a day.

What They Found

The authors found that there is no relationship between the knowledge domain of self-management and hearing aid benefit satisfaction. Therefore, it did not matter if somebody knew more about their hearing loss because they were not able to apply that to get more satisfaction from their aids. However, there was a relationship between age and knowledge. People who were older tend to demonstrate lower self-management in the knowledge domain.

In the action domain, they found that self-management scores were positively correlated with satisfaction on the scale of the satisfaction questionnaire. This means that people who had higher self-management abilities had greater satisfaction with the extent to which the hearing aids improved their speech understanding, reduced the need for repetition, and produced a natural sound quality. Being able to take action led to better satisfaction with hearing aids.

Psychosocial well-being was related to hearing aid benefit and satisfaction, accounting for a large amount of the variants in both domains. People who demonstrated better psychosocial well-being management reported less difficulty with background noise and reverberant situations. Additionally, they are more satisfied with the appearance of the aid and the extent to which other people perceived them as capable. This is a direct quote from the article: “...self-management statistically accounted for 18 to 26 percent of the variance in particular aspects of hearing aid benefit and satisfaction suggests that hearing loss self-management is one of the important components of hearing rehabilitation.” Therefore, they are strongly related.

Why Is This Important?

This information is important because it suggests that people who are better able to manage are more likely to succeed in difficult listening situations. It is not just about the hearing aid, but the psychosocial self-management aspect as well. The authors argue that this calls for a greater focus on the psychosocial aspect of hearing loss in patient-centered care. Incorporating patient-centered care could lead to better hearing aid satisfaction and benefit.

Does It Matter Clinically?

This information does matter clinically. We have identified many factors that can lead to hearing aid satisfaction. People who report more difficulties with unaided hearing are more likely to be satisfied. Also, people are more likely to be more satisfied with newer hearing aids when the hearing aid sounds good. However, this study suggests that self-management is a prominent piece of hearing aid satisfaction.

How Do Hearing Aid Owners Acquire Hearing Aid Management Skills? (Bennett, Meyer, & Eikelboom, 2019)

The next study shifts to hearing aid management, but we are still in the domain of self-efficacy. This article was published in 2019 in the “Journal of the American Academy of Audiology.”

What They Asked

Their initial question was, “How do hearing aid owners acquire hearing aid management skills?”

A Little Background

As hearing healthcare providers, we train hearing aid users to handle and maintain their hearing aids. We also know that hearing aid users have difficulty with this. As much as 90 percent of people have trouble managing some aspect of their hearing aids. There are some factors associated with hearing aid handling skills. Information technology-enabled services (ITES) are easier to manipulate than BTEs, and females are more likely to have difficulty. Some mistakes, such as putting a left hearing aid onto a right ear, can affect hearing aid handling skills.

Common clinical practice is a great way to train people on hearing handling skills. This would consist of 45 minutes of training averaged across two to five appointments over the first 30 to 45 days of oral rehabilitation. This occurs in face-to-face appointments and may be supplemented with written or digital materials such as handouts from the manufacturer or clinic.

There are some limitations to this approach. For example, it could be perceived as information dumping. This means that an audiologist is pouring information into the patient. Owners are unable to recall 25 to 65 percent of information only four weeks after they have been fit. There is evidence from 2010 that clinicians had a limited understanding of health literacy, which affects hearing aid handling skills and uptake.

Why It Matters

Hearing aid handling skills are essential for success. If you have trouble managing your hearing aids, you are less likely to use them or benefit from them. We need to help and support our patients in acquiring these handling skills.

What They Did

These authors used concept mapping to identify key themes. In that study, the participants first generate, sort, and rate the importance of the statements. The data analysis then pulls out some key themes. The question was posed to two different groups of participants, hearing aid owners and clinicians. They were asked to answer the question, “How do hearing aid owners learn skills required to use, handle, manage, maintain, and care for their hearing aids?” Those answers were then rated and sorted, and themes were identified.

They did this in two sessions. The first session consisted of brainstorming, which was the statement generation. People put out ideas, and the other participants in the group could then expand on the statements and generate their own. The clinicians and the hearing aid owners did not see each other’s statements, but they saw the statements in their group. The hearing aid owners did this in an in-person meeting, and the clinicians did it remotely. During the second session, the participants rate the statements and come up with a theme. They rated them by considering how often they used that mode of learning and how beneficial it was.

What They Found

These authors found six main concepts related to how hearing aid owners acquire hearing aid handling skills:

- Relationship with the clinician

- Clinician as a source of knowledge and support

- Hands-on experience

- Seeking additional information

- Asking support people for help

- External resources

When we think about the relationship with the clinician, an example statement of something in that theme would be, “Having a good relationship with the clinician, especially having open lines of communication to be able to ask for support.” It is about the therapeutic relationship.

The next concept is about the clinician as a source of knowledge. Asking the clinician to provide a simple overview of common hearing aid instructions through a cheat sheet would be an example statement from that domain. Hands-on experience is another important concept. For example, trying new things if they cannot do what the clinician has instructed. This could mean showing the patient different ways to insert the hearing aid. Seeking out additional information was prominent as well. This means repeatedly asking questions until they get an answer that makes sense to them.

The fifth concept is asking for support from other people. Ask partners and family members to attend appointments, or to do it for them. External resources are about accessing information through mediums other than the clinician. These mediums could include newsletters or borrowing books.

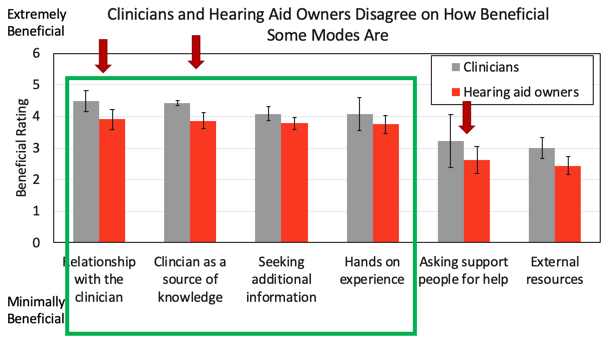

Both groups of participants rated how often they did these things and how useful they were. Out of the six concepts, they were all used similarly. However, it was reported that the relationship with their clinician is used less than the clinicians rated it. As you might imagine, all of those modes of learning were equally useful. Figure 1 shows how useful clinicians and hearing aid owners rated each statement.

Figure 1. Patients were less likely than clinicians to think asking for help (i.e., friends, family) is helpful, the relationship with the clinician was helpful, and the clinician as a source of knowledge was helpful.

Hearing aid owners and clinicians agreed about the relative utility of each domain. However, hearing aid owners also felt that a particular thing was less useful than the clinicians. Those differences were significant and are represented by the red arrows. They are rank-ordered, so the most helpful thing by both groups of participants was the relationship with the clinician. That relationship and using the clinician as a source of knowledge were the most useful ways in acquiring hearing aid handling skills.

In general, the relationship with the clinician, using the clinician as a source of knowledge, seeking additional information, and hands-on experience was deemed useful. On the other hand, asking for support from others and using external resources were rated as less useful by both groups. The authors thought this because the hearing aid owners’ baseline skills are too low. If you do not have many skills in the first place, trial-and-error will not help. We may be able to help increase their trial-and-error techniques by empowering the patients and helping them acquire baseline skills beforehand.

Another concept that came up as not useful was reading pamphlets. This study was conducted in 2015. Around that time, there were other studies that documented the readability of the hearing aid manufacturer and clinic-specific pamphlets. It turns out that those pamphlets were not readable because they were written at high-grade levels. It may be that those pamphlets are more useful now than they were in 2015. However, the authors think that the readability of the pamphlets contributed to the low benefits of the external resources.

Why Is This Important?

This information is important because it gives us insight into how we can help support our patients’ knowledge of hearing aid handling skills. It is our job to help them and support them as we play an important role. It is also clear that we are not the only person who plays a role, and the role of family, friends, and external others was low as of 2015. We could improve that by including spouses or friends in the training. We could also put general training out in the world at large. This way there is a bigger resource network to help our patients acquire these hearing aid handling skills.

Does It Matter Clinically?

This information does matter clinically. The authors suggest that we enhance our hearing aid owners acquisition skills by using more diverse methods. Instead of doing face-to-face training and sending them home with a brochure, we could develop personalized training programs, give them the opportunity to learn, and demonstrate practice during those appointments. We could also give support materials that are written at an appropriate grade reading level in order for them to be understandable and digestible. This then empowers the client throughout the hearing aid fitting process.

Specific recommendations from the authors would increase the use of tactile training methods. Have the patients demonstrate for you in the office or remotely that they can do these tasks. Tailor training goals by focusing on specific tasks in the first few weeks and then broadening to the more difficult ones. Supplement the training with these digital and written materials by using easily read materials and targeting them towards the caretaker. Develop a strong therapeutic relationship, as well. The authors recommend unbundling price structures to put a value on the services provided. This way, we do not just put hearing aids on and send them out the door.

Factors Associated With Successful Setup of a Self-Fitting Hearing and the Need for Personalized Support (Convery, Keidser, Hickson, & Meyer, 2019).

This next article looks at self-efficacy. When we think about how our service delivery models are changing, this article addresses the factors that are related to somebody being self-efficacious during the fitting process for hearing aids.

What They Asked

The authors wanted to know if there were personal factors that would help predict whether or not somebody could self-fit a hearing aid. If we could identify these factors or who would need more support, we could then tailor our services based on the individual patient. The authors were interested in a couple of factors of interest, cognitive status, locus of control, hearing aid self-efficacy, and problem-solving skills.

A Little Background

Changes in our hearing healthcare system are here. This includes over-the-counter hearing aids and implementing limited service delivery models. We are also in the middle of a global pandemic, which has changed the ways that we deliver our services. Self-fitting hearing aids or identifying the factors that are related to needing a lower service delivery model can help us. Tailor those services to best meet the needs of your patient in the current environment.

A self-fitting hearing aid is a specific way to look at this, but this is a personal amplification device that is designed to be set up and managed by the user. A hearing aid user would need to select, connect, and adjust the components. For example, the tubing and the domes would do audiometry through the hearing aid. The hearing aid would then apply a prescriptive fitting rationale to the measured threshold, and the user can fine-tune or train the settings.

There are some things that are different about a self-fitting hearing aid from a traditional hearing aid. In a traditional hearing aid, the user could have fine control. As an audiologist, you could prescribe and fit the hearing aid and send them out the door. However, the user is now involved in the selection, the setup, and the audiometry. This is the part that is different. The reasons that the authors were interested in that list of personal factors is because an intact cognitive status, higher self-efficacy, and internal locus of control are associated with successful hearing aid use. Locus of control is the extent to which an individual believes that they can influence the events in their own lives. Additionally, manual dexterity and health literacy are associated with day-to-day hearing aid management tasks.

Why It Matters

This is important because establishing those factors that can facilitate limited service delivery options can help us expand our clinical practices. You want to meet a larger need of people who have hearing loss and have more hands-on time for people who need it. That is going to help us individualize our hearing healthcare, broaden our clinical practice, and reach a broad spectrum of patients.

What They Did

These authors measured patient factors. They considered health locus of control using the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale. This looks at the extent to which somebody believes that the events in their life are the result of a powerful other or chance. They measured hearing aid self-efficacy using the Measure of Audiologic Rehabilitation Self-Efficacy for Hearing Aids. It goes over basic handling skills, advanced hearing aid handling skills, and adjustment hearing aid-related skills. They also did a problem-solving skill test, which is the Twenty Questions subtest of this executive function system test. The participant asks the examiner a series of questions and tries to guess what the answer is based on those 20 questions. They measured the cognitive status using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). They also measured demographic data and hearing thresholds. They then sent the patients home, brought them back, put them in a room, and said, “Here are the tools you need. I want you to self-fit this hearing aid. If you need help, call the center.”

They were instructed to complete this nine-step process:

- Pair hearing aids to a mobile device via Bluetooth.

- Identify the right and left aids.

- Select the correct ear tip size.

- Adjust the length of the tubing.

- Insert the hearing aids into the ear.

- Ensure the fitting app correctly identifies the aids.

- Use the app to perform audiometry.

- Adjust the settings.

- Learn how to clean and care for the aids.

The authors judged the degree to which people could do each of these steps. To provide support for the patients, the authors wrote the instructions at a 5.8 grade level. They also provided captioned videos of what they thought would be the hardest steps. They had a telephone available for the clinical assistant in order to monitor the participant’s progress. They can then judge whether or not they successfully completed those tasks. The successful self-fitter accurately completed all steps independently with or without help from that clinical assistant. An unsuccessful self-fitter had unresolved errors. Therefore the hearing aid was never successfully fit, and they were not ready to go out in the world with it.

The participants were 60 adults aged 50 to 85 who had pure tone averages between 25 and 65 dB. Thirty of them were experienced hearing aid users, and the other 30 people had no hearing aid experience. The hearing aid was the Sound World Solutions Companion, a 16-channel instrument with noise reduction, directional microphones, rechargeable, and feedback cancellation.

What They Found

They found that two-thirds of the participants were successful, and one-third were not. Those who were successful were more likely to have a hearing aid experience and to own a mobile device. Of those successful self-fitters, 63 percent sought help from the assistant. Only 15 people were able to self-fit hearing aids without assistance. The people who were more likely to seek help also were more likely to have an external locus of control. This makes sense because an external locus of control means that they think the events that happen to them are the result of outside, so they are more likely to reach out for help. They also found that there was no single step where people got hung up. The errors were evenly distributed across those nine steps, and one participant could not successfully complete any of the tasks. In terms of where and when people needed help, they were often related to aspects regarding Bluetooth.

Why Is This Important?

This is important because it means that a large population may not be able to independently self-fit a hearing aid. There is a large part of the population who is going to need help and may not be able to do it in a remote context. These limited service delivery models would be better suited to people who already have hearing aids and already own mobile phones.

Does It Matter Clinically?

Clinically, this information does matter. Participants represent a biased sample of the population because they were willing to come in and were engaged. The percentage of successful hearing-aid fitters who are in the world might be lower. The study also provides some evidence that we need trained support personnel, even in a limited service delivery model. This is because few of those participants were able to do it both independently and successfully.

The clinical assistants commented that the telephone support aspect was challenging because it was difficult to troubleshoot the problems that they could not see. Participants could not always describe what the problem was and also had difficulty hearing them talk over the phone. The advice from the clinical assistants was to do this with a webcam. That could help them better troubleshoot without having to make an in-person visit.

The Effect of Hearing Aid Use on Cognition in Older Adults: Can We Delay Decline or Even Improve Cognitive Function? (Sarant et al., 2020)

The relationship between hearing loss, hearing aid use, and cognition has been of great interest over the last couple of years. One of the challenges of research is coming up with definitive answers to our questions because it takes a long time. The next two studies address important topics around cognition, hearing loss, and hearing aids. The first study by Julia Sarant and colleagues in Australia looks into how hearing aids interact with cognition.

What They Asked

This study asked different questions: What about potential hearing aid users? For those who have not yet received a hearing aid, is hearing loss related to cognitive impairment in those cases? Can we test and find that hearing loss and cognitive impairment might actually be related? The authors had people use hearing aids and posed a question: after 18 months of hearing aid use, are there changes in cognition in older adults? Does that affect quality of life?

A Little Background

One of the reasons this topic has been of great interest is because we think that there is going to be a large increase in the prevalence of dementia. There are predicted to be 131 million individuals who experience cognitive impairment within 30 years or so. Regarding hearing aids and cognitive impairment, about two-thirds of dementia risk is genetic. However, more recent studies have shown that approximately one-third of the remaining cases may be delayed through modifying some risk factors. Whether we improve education, reduce smoking, or manage diabetes, those have been identified as potential risk factors associated with the beginning of cognitive decline. In particular, hearing loss has been identified as a modifiable risk factor for dementia in older adults. It may account for up to almost 10 percent of the modifiable risk.

One study looks into the relationship between hearing loss and mild cognitive impairments, and dementia seems to be the strongest in those who are aged 45 to 64. This is important because only a few older adults use hearing aids that have hearing loss. We have heard the data that somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 percent or so of adults with hearing loss use hearing aids. Hearing aid use is lowest level in adults with more mild hearing loss and older adults who are younger.

This range is where there seems to be the strongest association between dementia and hearing loss. Other research through the meta-analysis of existing data suggests those who use hearing aids have better cognition than those who remain untreated. It even suggests that there may be a relationship, there is no evidence yet that this relationship is causal. What do we mean by that? What do we mean not causal? If we see a relationship, why would we not think that one causes the other? Why does increased hearing loss not increase the risk for cognitive decline?

Related to hearing aid use, we know that those with better cognition are more likely to seek hearing treatment. Therefore, there is a bias in the meta-analysis studies because those who use hearing aids are more likely to have higher cognition, to begin with. When we just consider hearing loss and cognition, there is an issue of an underlying causality related to aging. Neuropathic and microvascular changes we see associated with aging increase the risk of both hearing loss and cognitive decline. There may be underlying factors that are increasing risk for both.

Why It Matters

Why does this matter? Cognitive decline has some devastating outcomes. It has a large cost associated with it, and there is increased caregiver burden. Additionally, those with cognitive decline experience a large range of negative consequences, including reduced quality of life. If we could delay onset cognitive decline, we would have a positive impact on individuals and healthcare systems worldwide.

What They Did

This study looked at 99 participants aged 60 to 84 years old. They identified people that had no history or previous diagnosis of cognitive impairment. They are looking at older adults who are in a normal cognitive range. Seventy-one percent of the participants were retired, and 67 percent had postgraduate tertiary education. Comparatively to the population at large is this is a particularly well-educated group of individuals. They were clients of the University of Melbourne Academic Hearing Aid Clinic.

All of the participants completed a preoperative assessment battery. This included audiometry and speech perception testing. Additionally, a variety of cognitive testing was used as well, including health questionnaires, quality of life questionnaires, and life and ease of listening questionnaires.

There were 99 participants. Hearing aids were chosen through a needs discussion with the participants. They were all fit with the NAL-NL2 prescription. There was then a follow-up appointment after 8 months of hearing aid use with 37 participants, using an identical battery that included reported hearing aid use and hearing aid usage logs.

What They Found (Baseline)

Let’s first consider the 99 original patients. What did they find at the baseline? They determine that increased age, less education, and greater hearing loss were all correlated with poor executive function. Specifically, 10 dB of hearing loss was associated with a decrease of about 7.5 percent of executive function relative to the mean score. That is after controlling the other explanatory variables, including age. Every 10 years of increasing age was associated with a decrease of executive function of about 14 percent. Additionally, having a good education was associated with an increase of executive function. However, in terms of its negative impact on executive function, 10 db of hearing loss is approximately equivalent to five years of aging because the effect on executive function was about half as large.

What They Found (Follow-Up)

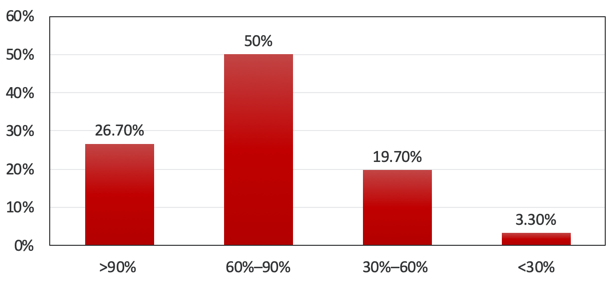

In terms of follow-up, if we want to know the impact of hearing aid use on cognition, we have to know whether the patients actually use the hearing aids. Figure 2 is a visual representing hearing aid use. This is the data that they reported in tabular form from the hearing aids themselves:

Figure 2. Hearing Aid Use (percent of hours awake).

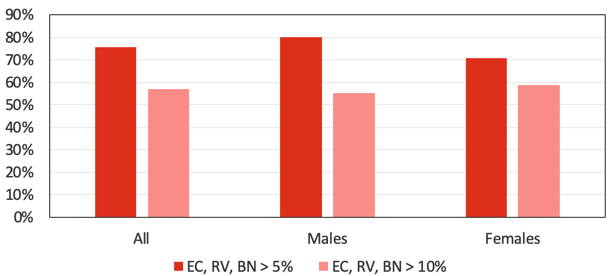

If we add the first two columns together, about 77 percent of individuals used hearing aids for at least 60 percent of waking hours. Given that there are 37 people, the column on the right shows one individual out of the group that uses the hearing aid less than 30 percent of waking hours. Did these individuals benefit from the hearing aids? In the red bars, the individuals that got at least 5 percent benefit in the ease of cognition, reverberation, or background noise of the abbreviated profile of hearing aid benefit (APHAB). The pink bars represent the individuals that got about a 10 percent benefit in at least one of those subcategories. The vast majority of individuals received at least 5 percent of the benefit in some of the subcategories. The majority actually received at least 10 percent benefit. I also want to draw your attention to the concept of males versus females, shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3. APHAB Benefits.

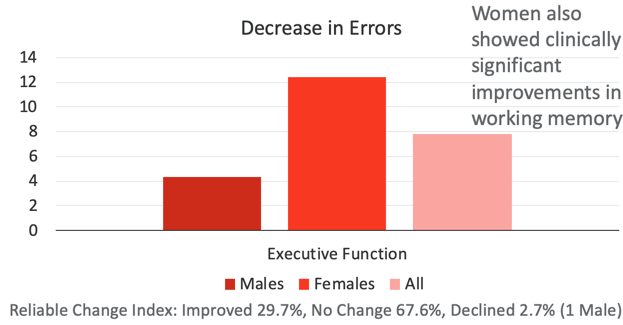

The higher pink bars for females suggests that more females in this study were receiving larger benefits on the APHAB sub-scales. That is greater than 10 percent benefits. One of the most compelling results of this study relates to executive function as a subset of cognition. Figure 4 looks at the decrease in total errors:

Figure 4. The decrease in errors.

There was a significant decrease in errors and a significant increase in executive function when all individuals were considered. This is the first study I am aware of that proves hearing aid use can increase executive function for all. Even though this is a small group, another interesting finding is the male-female difference. This is because the benefit in executive function is larger for females comparatively to the males. Applying a different statistical analysis called the reliable change index, they went through and tried to determine who had clinical improvement versus no change or a decline in executive function. Considering both males and females, about 30 percent of individuals showed clinical improvement and 67.6 percent showed no change. Only one male showed a decrease in executive function over the 18 months of hearing aid use. In addition, women showed clinically significant improvements in working memory that were not seen in men.

Hearing Aid Use Helps?

What do these results tell us? In this group of 37 participants, there was improvement in executive function associated with 18 months of hearing aid use. All but one male showed stable or improved cognitive function. Stable or improved psychomotor function, working memory, visual attention, and visual learning was observed in 73 to 81 percent of participants. It was particularly present with women.

Why Is It Important?

This is important because it is more information that suggests treating hearing loss with hearing aids may delay cognitive decline.

Does It Matter Clinically?

This study does matter clinically, but it is still limited. If the information is found to be true, the impact would be prominent. However, we have to recognize that this is a relatively small sample size. It is not definitive evidence that hearing aids slow cognitive decline. This is because there is no control group to see what happens without 18 months of hearing aid use. Regardless, it is the first evidence that hearing aid use can improve executive function in some older adults.

Other Considerations

This study focused on older adults with no history of cognitive decline. For many of us, we also have interests in whether those with cognitive decline or mild cognitive impairments also might show some of these benefits. Can we not only delay the onset of cognitive decline, but can we also slow the progress of cognitive decline once it begins? That is something of considerable interest.

Experiences of Hearing Aid Use Among Patients With Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia: A qualitative study (Gregory et al., 2020)

We want to know whether those with cognitive decline use hearing aids and experience challenges relative to their use. In this small, qualitative study, the authors were interested in experiences of hearing aid use among patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia.

What They Asked

The authors note that those with dementia are at an elevated risk for experiencing reduced quality of life, increased social isolation, and depression. We have existing data that shows hearing aids can improve those factors for adults with normal cognition. There is a potential for benefit from hearing aids in individuals with dementia that are unrelated to cognitive decline. Their main question was, “what are the barriers to hearing aid use in individuals with mild cognitive impairment?”

A Little Background

Over half of 85-year olds using hearing aids report that their quality of life is either “quite a lot” or “very much” better because of their hearing aids. Hearing loss is more common in people with dementia and it has been identified as a risk factor for dementia development. Perceived hearing handicap, comfort, limited perceived benefit, high cost, and perceived difficulty with hearing aid use have all been previously identified as barriers to hearing aid use in cognitively healthy older adults. As the authors point out, cognitive ability has rarely been studied as a potential barrier. We know from previous research that cognitive status at the time of hearing aid use is associated with that use. This is especially the case with those who have more cognitive decline and are more likely to stop using their hearing aids.

Why It Matters

This matters because individuals with mild cognitive impairment and their caregivers have the potential for multiple benefits if cognitive decline is delayed. Identifying and eliminating any potential barriers may help increase hearing aid use with those who have mild cognitive impairment.

What They Did

There were 10 adults recruited from four memory clinics within one mental healthcare system in the United Kingdom. This was a qualitative research design that included semi-structured interviews. Participants were interviewed in the research facility or in their own homes. Family members were sometimes present at these interviews, but they did not contribute.

What They Found (Themes)

The authors identified four themes:

- Theme #1: There are memory and cognitive barriers to using hearing aids.

- Misplacing hearing aids, forgetting to use them, etc.

- Theme #2: There are device use barriers

- Need help with use/insertion/batteries, too loud in some situations, interfere with glasses

- Theme #3: Hearing aids provide benefits

- “There a help, at least in some places”

- Theme #4: There are barriers related to ambivalence and stigma.

- I am not sure they really help that much.

- People will view me as disabled and there is not as much support (in the general population) for hearing loss as (for example) blindness.

The first theme is the memory and cognitive barriers to hearing aid use. The remaining themes are seen in older adults without cognitive impairments. There are device-use barriers, so they need help with insertion, batteries, they’re too loud, they interfere with glasses. There are barriers related to hearing aid benefits, but most individuals noted that the hearing aids did provide benefits. In this population, they got benefits even though there were barriers. Finally, there were previously reported barriers related to ambivalence and stigma, such as being viewed as disabled.

Conclusions

In conclusion, many of the barriers associated with hearing aid non-use in those with normal cognition were also identified in this study. However, participants in this study viewed memory loss and cognitive impairments as detrimental as well. However, many of them talked about how they overcame these memory-related difficulties. They mentioned reinforcing device benefits, continued perseverance, and the importance of family support.

Does It Matter Clinically?

When we think about this clinically, it is important to understand that those with mild cognitive impairment are going to have additional barriers. Highlighting the potential benefits for the patients and their caregivers and recognizing the importance of caregiver support for success in hearing aid use in this population is crucial.

How Can These Learnings Translate in the COVID-19 Era?

Consider how our worlds have changed in the last three months and how we have been pivoting our clinical services. Think about the results of this study and what they mean for this remote service delivery model. The three articles that I summarized highlight the importance of trained personnel, even in those low service delivery models. Self-management is an important part of hearing aid benefit, so it would be great to help our patients learn to self-manage their hearing loss, especially regarding psychosocial aspects. Self-management of hearing aids is also important with hearing aid satisfaction. We can still help our patients, even in this new world that we find ourselves in. The clinician has a large role, but they are not the only ones. It would be great to involve family members or friends who live with the patient because they then do not have to commute. It is also helpful if you are doing a remote fitting or follow-up, they will be at home.

Finally, the last study highlights the need for assistance and suggests that not everybody is a good candidate for limited service delivery models. It is important to think about tailoring the level of support to the patient. Patients who are existing hearing aid users and have mobile phones would most likely be better off.

References

Bennett, R. J., Meyer, C. J., & Eikelboom, R. H. (2019). How do hearing aid owners acquire hearing aid management skills?. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 30(6), 516-532.

Convery, E., Keidser, G., Hickson, L., & Meyer, C. (2019). The relationship between hearing loss self-management and hearing aid benefit and satisfaction. American journal of audiology, 28(2), 274-284.

Convery, E., Keidser, G., Hickson, L., & Meyer, C. (2019). Factors associated with successful setup of a self-fitting hearing aid and the need for personalized support. Ear and hearing, 40(4), 794-804.

Gregory, S., Billings, J., Wilson, D., Livingston, G., Schilder, A. G., & Costafreda, S. G. (2020). Experiences of hearing aid use among patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease dementia: A qualitative study. SAGE Open Medicine, 8, 2050312120904572.

Sarant, J., Harris, D., Busby, P., Maruff, P., Schembri, A., Lemke, U., & Launer, S. (2020). The Effect of Hearing Aid Use on Cognition in Older Adults: Can We Delay Decline or Even Improve Cognitive Function?. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(1), 254.

Citation

Ricketts, T. & Picou, E. (2020). Vanderbilt audiology journal club: cognition and self-efficacy. AudiologyOnline, Article 27025. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com