This text-based course is a transcript of a live seminar. Please download supplemental course materials.

Gus Mueller: Welcome to the Vanderbilt Audiology's Journal Club. We are finishing up our third year; this is our 16th recorded Journal Club. At our club meetings, we discuss articles that are relatively recent, focus on a specific topic, and are pertinent to audiology clinical practice. We invite you to check out all the journal club courses in the AudiologyOnline library.

Before we turn things over to our presenter, Dr. Gary Jacobson, we have a few special features that are part of all our journal club sessions, What They are Reading at Vandy and of course, Gus’ Pick of the Month. These features enables us to cover a few additional articles of interest. This month, however, we're combining these two features into one, and the topic works well with Dr. Jacobson’s discussion of self-report measures in the assessment of dizziness and vertigo.

What They’re Reading (and Writing) at Vandy

My colleague here at Vanderbilt, Todd Ricketts, and Ruth Bentler of the University of Iowa and I are working on a book related to hearing aid fittings, and one of the chapters in this book has to do with pre-fitting self-assessment inventories. These are paper and pencil or computerized inventories that you would give to a patient before the hearing aid fitting. I thought since Gary’s topic today relates to questionnaires, that I would give you a glimpse into seven good questionnaires that you might want to try out with your hearing aid patients.

I think you are already familiar with some of them, but others might be new to you. My purpose today is to simply alert you to what is available. If something strikes your fancy, you certainly can check it out further, or start using it if you want.

HHIE/HHIA

One of the questionnaires that has been around as long as any is the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE; Ventry & Weinstein, 1982) or the Adult (HHIA; Newman, Weinstein, Jacobson & Hug, 1990). Age 65 is the cutoff between the Adult and Elderly versions, and you will see one or two different questions, but basically the scales are pretty similar. The goal of the questionnaire is to measure the degree of handicap for emotional and social issues related to having a hearing loss. In general, we are trying to answer the question, “How much does the hearing loss bother this person?”

APHAB

The next questionnaire is the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) developed by Robyn Cox and colleagues. When you conduct a pre-fitting APHAB, what you are looking at is the percent of problems that the patient has for different listening situations involving understanding in quiet, in background noise and in reverberation. It also looks at how much the patient is bothered by loud environmental sounds, referred to as the “aversiveness scale.” So on the surface, perhaps, some of you might think that the HHIE and the APHAB are looking at the same thing, but they are not. Consider that a person could have problems understanding in many different situations, yet it does not cause a social or emotional handicap for them. On the hand, some people have little understanding problems (good APHAB), but feel handicapped by this mild impairment (poor HHIE score).

Two other self-assessment scales that are, again, somewhat similar are the Expected Consequences of Hearing Aid Ownership (ECHO; Cox & Alexander, 2000) and the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI; Dillon, James, & Ginis, 1997). The ECHO helps to examine expectations in four different areas using 15 questions. One area is positive effect, meaning, what does the patient expect are the benefits of using hearing aids? Do they think they are going to be able to understand 100 percent of speech in noise once they start using amplification? Other areas of the ECHO are service and cost, the patient’s expectations about negative features and personal image. Does the patient think the hearing aids whistle? Does the patient think they will make them look older?” You can look at these expectations and use the scores to help guide you in your pre-fitting counseling.

Similar to this, but not the same, is the COSI. Many of you have used the COSI as a measurement of hearing aid benefit, but it is also possible to use the COSI for patient expectations. You work with the patient to identify three to five specific listening goals or communication needs—these should be selected by the patient.. These can then be used to measure patient expectations related to these specific goals. You might say, “I’d like to see your expectations. Tell me how you believe you will be performing a month or so after you have been using hearing aids.” Then the patients rate their expectations. These should be very specific areas that you can focus on, and, depending on what the patient says, you may want to do pre-fitting counseling. If your patient thinks that he is going to go to the neighborhood pub and understand 100 percent of what is being said with his new hearing aids, then you might want to talk to him about realistic expectations before you send him out the door with the hearing aids.

Two more scales that we believe are certainly worth trying are the Hearing Aid Selection Profile (HASP; Jacobson, Newman, Fabry, & Sandridge, 2001) and the Characteristics of Amplification Tool (COAT; Sandridge & Newman, 2006). Dr. Jacobson was instrumental in developing the HASP. It examines eight different factors related to the use of hearing aids, such as motivation, expectations, cost, et cetera. But it also looks at the patient’s needs and their lifestyle, and it gives you an idea of how your patient compares to the average listener. Conveniently, this is all computer scored for you. Where else can you get the link for the form and the scoring but at AudiologyOnline? (Jacobson, 2012; https://www.audiologyonline.com/ask-the-experts/hasp-self-assessment-inventory-13).

Similar to the HASP is a shortened version called the COAT. This only has nine questions, but it gets at similar things as the HASP. Some people believe the HASP was a little too long to administer. The article about the use of the COAT was published, again, right here at AudiologyOnline (Sandridge & Newman, 2006; https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/improving-efficiency-and-accountability-hearing-995).

Finally, a test that Catherine Palmer and I developed almost 15 years ago is called the Profile of Aided Loudness (PAL; Mueller & Palmer, 1998). We realized that a large part of fitting hearing aids and subsequent success was providing normal loudness perceptions. Our goal was to see if we could come up with a scale that the patient could complete, which would give us an idea about real-world loudness perceptions and how satisfied patients are. In this case, you would want to look at the unaided results, because you are going to need those to compare to the aided results to see if loudness perceptions are more appropriate.

So those are seven different pre-fitting self-assessments I think you might want to try out. They probably will not change the technology that you are going to fit, but they certainly make you a much better counselor. And as you all know, that oftentimes is half the battle when you are fitting hearing aids.

Well, let’s move on to our headliner for the day. Dr. Gary Jacobson is Professor and Director of the Division of Audiology at Vanderbilt. He is in charge of the clinical services for the Vanderbilt Audiology Clinic and Co-Director of the Vestibular Lab. Gary is also very actively involved with our Ph.D. and Au.D. students and is the go-to guy for a host of different things. Dr. Jacobson has also recently taken on the role as the editor of the Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, which is a huge job. Thanks for your willingness to assume such an important job for our profession. So, with that, Gary, over to you..

Gary Jacobson: Thank you for the opportunity to contribute again. This time, I decided to stay away from discussing how to do tests and how to interpret test results, and thought instead that I would talk about useful paper-pencil measures that we use in our clinic and the sort of information that these test can provide. What we try to teach our students to do in the clinic is to be a step ahead of where they are at in the test battery, so that they can begin to predict what the result of the next test is going to be based on the previous test. In our laboratories, we usually begin with bedside tests, and we use these to create hypotheses for what we expect to see when we do quantitative testing.

In addition to bedside tests like the head-shake test and the head impulse test, we also administer a standardized case history, a screening instrument for anxiety and depression, and then a measure of dizziness disability handicap in hopes of identifying chronic subjective dizziness, which is an anxiety-based dizziness for the most part. The paper-pencil scales that I am going to be talking about briefly today include The Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI; Jacobson & Newman, 1990), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983), Structured Interview for Migrainous Vertigo, referred to as a (SIM-V; Furman, Marcus, & Balaban, 2003), and then an “expert” structured case history. The first three are fully formed and ready to be used and the last is still being developed.

So by way of background, the DHI is designed to be an income and outcome instrument. You can certainly develop your own questionnaires and outcome measures, but in order to be useful in a test/retest basis, they need to be standardized, and it takes a bit of time and energy to do that. There are general outcome measures or quality of life measures, and then there are more disorder or modality-specific outcome measures, like the HHIE, the DHI, and the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI; Newman, Jacobson, & Spitzer, 1996).

Why do we want to administer some of these scales? First, they provide evidence to patients and third-party payers that what we do diagnostically is useful. If we do therapeutic types of activities, it shows that what we are doing actually results in improvement in a person’s quality of life. Another reason is that they provide unique information that you cannot estimate from quantitative tasks. We can take ten people with unilateral weaknesses on caloric testing and they potentially will have ten different levels of disability handicap. The last reason is that the information from these measures is sometimes diagnostic. They can help you narrow down the possibilities of what you are going to suggest be added to the differential diagnosis for that patient.

When it comes to measuring dizziness disability, there are some disability/handicap measures that have been developed. Craig Newman and I developed the DHI in 1990. Yardley and Putnam (1992) developed the Vertigo Handicap Questionnaire, which is very similar to the DHI. Neil Shepard and his colleagues (1993) then developed something called the Subjective Disability Scale/Post-Therapy Symptom Score. Other measures that you can use in your clinic include the Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale (Powell, & Myers, 1995), the UCLA Dizziness Questionnaire (UCLA-DQ), and the Vestibular Disorders Activities of Daily Living (VADL) Scale (Cohen, & Kimball, 2000).

Dizziness Handicap Inventory

I want to isolate the DHI for a moment. For those of you who are unfamiliar with it, it is a 25-question scale. If you have experience with the HHIE or HHIA, the platform is very similar, partially because some of the same people that developed the DHI also developed the HHIA, the THI and some other outcome measures. It is designed to measure the impact the dizziness and unsteadiness has on a patient’s quality of life. The word dizziness is not used in the questions, however.

For example, one question says, “Does looking up increase your problem?” We use the word problem or your problem so that the device can be useful for patients who are dizzy and not vertiginous, or unsteady as well. A yes, as with the HHIE, is scored 4 points, sometimes 2, and a no gets 0 points. With 25 items, the maximum self-report handicap is 100 and the minimum is 0.

It originally had three subscales: functional, emotional, and physical. Initially, we placed items in the DHI into these subscales empirically; but later on, other investigators tested statistically whether the items that we had placed in these three subscales actually belonged there, and found that we had made assumptions that probably were not statistically supported. So the recommendation is that the DHI total score is really what you should be spending your time looking at, not the subscales.

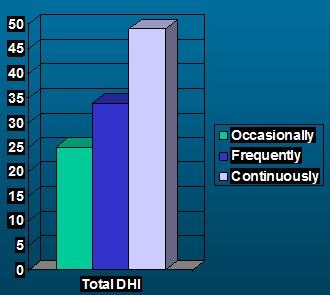

The DHI is psychometrically strong. It has a test-retest reliability of 0.97. We know from that work that you have to have a net change of plus or minus 18 points or more for the change to be significant at the 0.5 level. It has various types of validity. In Figure 1, we were just looking at frequency of dizzy spells and the effects on the total score of the DHI. You can see that as the frequency of spells increase, so does self-report handicap as noted by the DHI score.

Figure 1. Score of DHI as a function of frequency of dizzy spells.

We have taken large datasets and created interquartile ranges that we then use to classify total scores on the DHI as representing no, mild, moderate, and severe self-report handicap. It has also been translated into 18 different languages.

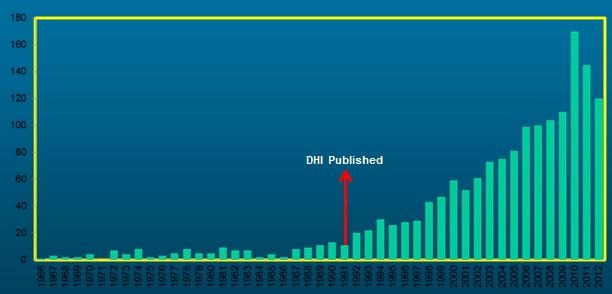

Figure 2 is courtesy of Dr. Erin Piker. This shows how many reports had been published about Dizziness Disability/Handicap in 1991 when the DHI was developed. The time spans from 1966 to 2012. This just goes to show that once questionnaires or intakes are available for people to use, they begin to be used. There has been a steady growth in interest on the impact that dizziness and vertigo have on a patient’s life.

Figure 2. Frequency of report of dizziness disability or handicap from 1996-2012. Reports were noted to rise after the publication of the DHI in 1991.

Aside from obvious clinical applications, what can you do with standardized self-report measures? That takes us to the report from Sue Whitney and her group (2005) at the University of Pittsburgh, Usefulness of the DHI in the Screening for BPPV (benign paroxysmal vertigo). By way of background, BPPV affects an estimated 17-22% of patients seen in a dizziness clinic, and the peak reporting age is in the 60s. It is evoked or provoked with either the Dix-Hallpike or the head-roll test. What Whitney and colleagues proposed was that positive endorsements on the DHE, specifically yes or sometimes, would give you means to increase your level of suspicion that BPPV might exist for that patient. They hypothesized that responses to five items drawn from the total DHI could assist physicians or audiologists in making an accurate diagnosis of BPPV.

The content of these five items were the effect of looking up, difficulty getting into or out of bed, quick head movements, rolling over in bed, and bending over. So they took 5 items out of the 25-item DHI and then created a 5-item and 2-item, in my words, mini-DHIs. The 2-item mini-DHI used the questions relating to difficulty getting into or out of bed and discomfort when rolling over in bed.

They did a retrospective chart review of 373 patients from 1998 to 2003. Twenty-two percent of the group had a diagnosis of BBPV with a positive Dix-Hallpike maneuver. The total scores on the DHI were similar between the BPPV group and the non-BPPV group. The subscale score mean for the BPPV group was 12.5, compared to 10.7 for the non-BPPV group. They computed likelihood ratios and estimated probabilities, based on the responses of patients to the 5-item and the 2-item versions.

They found that patients scoring 20 points on the 5-item mini-DHI had a 35% probability of having BPPV. Those scoring two yes’s on the 2-item questionnaire, for a total of 8 points, had a 4-fold risk of having BPPV. Looking at this, I think you can see that if a patient had completed this DHI before they came to see you and you only looked at the 5 items or 2 items from the total scale, you could estimate how likely it would be that you could demonstrate positive Dix-Hallpike or head-roll tests.

So, what, if any, is the usefulness of the mini-DHI? It is short to administer, it provides a means of hypothesizing what the results will be of other tests like the Dix-Hallpike or head-roll. It could be used as a screening tool for internal medicine or geriatrics, and in so doing, possibly gate the flow of patients going to imaging, specialists or subspecialists.

Structured Interview for Migrainous Vertigo

The second measure I wanted to discuss briefly today is called the Structured Interview for Migrainous Vertigo (SIM-V). Let me start with some background. Migraines are a common problem; an estimated 28 million Americans suffer from migraine headaches. About half experience migraines, but have never been diagnosed; 39% of migraineurs do not seek medical help, and 21% of those diagnosed discontinue medical care because they are unsatisfied with the result. Migraine sufferers have tried, on average, 4.6 different medications before they find an effective treatment.

About 90% of migraineurs have a primary relative with migraine headache. There is a female preponderance during and after adolescence, although migraines can decrease as menopause approaches and estrogen levels decrease. Headache can be scaled using an outcome measure called the Headache Disability Inventory (Jacobson, Ramadan, Aggarwal, & Newman, 1994) that my colleagues and I at Henry Ford Hospital developed in the early ‘90s. This brings us to the paper The Diagnosis of Migrainous Vertigo: Validity of a Structured Interview (Marcus, Kapelewski, Rudy, Jacob, & Furman, 2004) out of the University of Pittsburgh. Joseph Furman is a key player in this group, as is Rolf Jacob. These are neurotologists and otoneurologists at the highest level.

Migraine-associated vertigo, migraine-related vertigo, and migrainous vertigo are all terms that describe systems where migraine and vertigo co-occur. Migraine as the cause of vertigo is believed to occur in 35% of pediatric patients who are dizzy and approximately 6 to 9% of adult patients seen for dizziness.

From quantitative vestibular testing, we know that a number of different abnormalities have been reported for patients believed to have migrainous vertigo, and that includes spontaneous nystagmus, positional nystagmus, abnormal caloric responses, and abnormal posturographic responses. Importantly, Neuhauser and colleagues in 2001 developed criteria to define migrainous vertigo. Diagnosis of migrainous vertigo, according to the study, requires a lifetime diagnosis of migraine, and vestibular symptoms that are intermittent, more than simple dizziness, interfere with daily activities, and are not caused by any identified pathology. Additionally, one or more migraine symptoms must have occurred with episodic vestibular attacks, including migraine headache, photophobia, phonophobia, or migraine aura. Also, there is no hearing loss or neurologic or otologic pathology to explain the balance abnormalities. Using those criteria, they identified migrainous vertigo in 9% of migraine patients. So, roughly, 1 out of 10 migraine patients probably has migrainous vertigo based on that data.

Furman and colleagues (2003) took the Neuhauser (2001) criteria, and from it, developed a Structured Interview for Migrainous Vertigo (SIM-V), which is much like a flowchart. The structured interview results in a standardized application of the Neuhauser (2001) criteria. The study objective was to test the reliability of the structured interview, and compare that to the physician assessment that occurs separately.

The structured interview (Furman, et al., 2003) takes you through the Neuhauser (2001) criteria down to the final questions that asks if certain symptoms have occurred at least twice at the same time as the patient was experiencing either episodic balance attacks or increased severity of fluctuating balance symptoms. Those symptoms could be migraine headache, phonophobia, photophobia and migrainous aura, either visual or otherwise. If the patient answers positively or has affirmed each of the seven items, then you get a diagnosis of migrainous vertigo.

Seventeen patients participated in this study. They were evaluated by an otoneurologist for the diagnosis of migraine and a neurootologist for the diagnosis of migrainous vertigo. These patients were evaluated separately by a nurse who used the structured interview; 82% of the subjects also were retested, so that test/retest reliability could be assessed. The authors found that kappa – which you can think of as a correlation coefficient – was 0.75 or 75%, meaning excellent validity. The SIM-V was 71% sensitive and 100% specific for migrainous vertigo, with a test/retest reliability kappa value of 0.75.

The limitation of this study, of course, was the small sample size of 17. Moreover, all of these things depend on the patient being an accurate historian; that is going to be the weak link any time you are trying to do an analysis using case history or self-report data. The patient has to have a certain level of self-awareness. There is a need for a pediatric version if 35% of dizzy kids have a migrainous vertigo. The merits of this study are that it provides a standardized implementation of the Neuhauser (2001) criteria, and it provides a means for creating hypothesis regarding the vertigo.

Vandy Vignette

Mueller: Now it is time for the Vandy Vignette. This is where we present a connection between Vanderbilt and an event or person in audiology. For today’s vignette, we are going to go back in time to about 1974, is that right Gary?

Jacobson: Yes. It was 1974-1975, and I had applied to a number of distinguished universities to try to gain entrance to their Ph.D. programs. One of the universities I applied to was Vanderbilt University. On the wall of my office that I call my wall of shame, I have a couple of letters – one of them from Northwestern University and the other from Vanderbilt University. The Vanderbilt letter is a rejection letter, basically stating, “Nope, not going to let you in.” It’s a bit of irony that I enjoy, now that I am teaching as a professor here, so it’s all good.

Mueller: Interesting the way some things work out in life. And that takes us to your third article.

Jacobson: This one is entitled Effects of Fluvoxamine (Luvox) on Anxiety, Depression, and Subjective Handicaps of Chronic Dizziness Patients with or without Neuro-otologic Diseases (Horii, Uno, Kitahara, Mitani, Masumura, et al., 2007). The investigators start off by saying that there are two problems in the treatment of dizzy patients. First, some dizzy patients demonstrate normal quantitative tasks. They say they are dizzy, but when you finally test them, their tests come out normal. Then some patients show abnormalities on quantitative testing, but they do not respond to anti-vertigo medications. The researchers suggested that dizzy patients without abnormal quantitative tests most likely had some psychological or psychiatric disorder, and dizzy patients who did have positive tests without improvement on anti-vertigo medications also likely had a pre-existing psychological or psychiatric disorder. Furthermore, appropriate treatment of the psychiatric disorder would result in a remission of the dizziness. They suggested that these dizzy patients would have abnormal Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) scores and DHI scores, and that they would improve after taking an antidepressant medication, in this case, a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI).

The hypothesis was that the SSRI would be effective on self-report handicaps and anxiety or depression in neurotology patients by acting on whatever the co-morbid psychiatric disorders were. Horii and colleagues (2007) predicted a positive correlation between scores on the HADS and the DHI.

They started treating 60 subjects but ended up with 41. These were consecutive dizzy patients with or without neuro-otologic diseases, and they used Luvox SSRI as the prescribed treatment. The outcome measure was, in their words, a slightly modified Japanese translation of the DHI. However, it was more than slightly modified; it was completely different. Instead of 25 items, it had 14. Instead of a yes/no/sometimes response, it was a 1 to 5 Likert scale. Instead of a maximum score of 100 points, it had a maximum score of 70 points.

They administered the HADS and the DHI before and after 8 weeks of pharmacotherapy. The therapy for Week 1 was 100 mg of the SSRI per day, and for weeks 2 through 8, they doubled the dosage to 200 mg per day. They administered their version of the DHI and the HADS. The HADS is a 14-item, validated, self-report measure that is designed to identify patients with potentially clinically significant anxiety and/or depression. There is a maximum of 21 points and a minimum of 0 points. The maximum score is 3 per item and there are 7 items per subscale. The investigators used a cutoff value of 12 points; we use a cutoff value of 11 points. They believed the 12-point cutoff yielded 92% sensitivity and 90% specificity for anxiety and depression. This is another measure that patients can fill out and bring back with them to the clinic that you can score very quickly and obtain some idea of whether there might be significant coexisting anxiety and depression. This scale was developed in 1983, so it has been around for a while.

The otoneurological examination included spontaneous nystagmus testing, caloric testing, posturography and pure-tone audiometry. They divided the patients into two groups: group one had neuro-otologic disease and group two had normal neuro-otologic tests.

The baseline HADS depression and anxiety subscale scores for the two groups were pretty close. The anxiety subscale score was a little higher for group two, the group with normal neuro-otologic findings. They found a trend for there to be two subsets of patients: responders and non-responders. Responders demonstrated reductions in self-report of handicap for both dizziness handicap and anxiety and depression. The non-responders had either a non-significant decrease in handicap or HADS scores. The same trends were observed in group two as were in group one.

Thirty subjects from both groups had high pre-treatment HADS scores of 12 points or greater. There was a post treatment reduction on the HADS score in 67% of the patients from a mean of about 21 to a mean of about 16. The DHI also decreased from a mean of 55 to a mean of 42. The authors reported that, indeed, the HADS and the DHI co-varied. Subjects showing reductions in self-report dizziness handicap also showed decreases in anxiety and depression and vice versa. We know from our own work that was done by Erin Piker that there is a correlation on the order of somewhere between 0.48 and 0.60, between DHI scores and HADS scores.

The reason why we are interested in this is that we know from the work of Staab and Ruckenstein (2003) that there are subgroups of dizzy patients whose anxiety creates or accelerates the problem. They talk about chronic subjective dizziness and there being three types of anxiety-related chronic subjective dizziness for three months or longer. They described an otogenic subgroup, which are patients who have no pre-existing anxiety, have an otogenic event occur, and then get anxious afterwards. The anxiety is then what you are seeing in the clinic. There is a psychogenic group, and these are patients who have pre-existing anxiety or depression, and that drives the chronic dizziness to occur. Then there is an interactive variety, where the patient has a pre-existing psychiatric impairment and they have an otogenic event occur. Then the anxiety accelerates and creates the chronic dizziness.

The current study (Horii, et al., 2007) showed that 70% of groups 1 and 2 showed HADS scores greater than or equal to 12 points. The SSRI produced positive results in a limited number of patients. This suggests that many patients with chronic dizziness may have comorbid psychiatric diseases. We should note, however, that we cannot rule out a placebo effect since this was not a placebo-controlled study. The authors concluded that chronic dizziness in patients without evidence of neuro-otologic impairment should suggest the possibility of a psychiatric disorder, and that these can be identified with screening measures like the HADS. They also concluded that the action of the medication is on both the comorbid anxiety and depression that is either the primary source of dizziness or reaction to the neuro-otologic impairment. For me, it illustrates how the HADS can be used in the clinic to identify subgroups of dizzy patients, to help plan treatment, and then finally after treatment, to measure the effects. In our clinic, all patients are given the DHI and HADS at minimum. There are other questionnaires that we use as well.

Expert Case History

The last item I wanted to address is the use of an “expert” case history. I am sure you have the same problem that I do: case-history taking can be frustrating. We are trying to do an ocular-VEMP (vestibular-evoked myogenic potential), a cervical-VEMP, a VNG (video nystagmography), and a rotary chair test in two hours and still have a few minutes to write a report afterwards. That means the amount of time that you have for case history taking is usually limited. We are trying to obtain a lot of information in a short period of time, digest that information, and then begin to generate hypotheses that we are going to prove or disprove when we do testing.

Unfortunately, patients are patients. They have stories to tell. Sometimes the stories are helpful, sometimes not. In either case, the second hand on the clock is moving, and you are trying to be as efficient as you can with your time. You do not want patients to feel ignored, so you do listen to what they have to say, and you filter as they are talking. The important thing to remember is that the real grandfathers of modern dizziness assessment, Baloh and Honrubia (2001), believe that the case history is the most important part of the dizziness assessment, so keep that going in the back of your mind.

Commodore Award

Mueller: For those of you who are new to sitting in on the Vandy Journal Club, in each session we designate an article for the Commodore Award. This is in reference to Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt who made a very generous donation in 1873, which prompted the founding of Vanderbilt University. He also had his own steamship and his own train. The Vanderbilt sports teams, in fact, are known as the Commodores. So at each Journal Club meeting, our presenter gives the Commodore Award to an article that has particular importance, significance, relevance or is unique is some way.

Jacobson: For the Commodore Aware, I am nominating the work from Zhao, Piccirillo, Spitznagel, Kallogjeri and Goebel (2011). Joel Goebel is the Neurotologist at Washington University who, I think, was the driving force behind this particular project.

Expert Case History, Continued

A number of investigators, including us, have attempted to develop expert case history questionnaires that usually consist of if/then algorithms until a working diagnosis is obtained. It is sort of like a flowchart. If the patient answers yes to this question, they go off on one branch; if they answer no, they go off on a different branch. Unfortunately though, attempts to develop expert questionnaires have been met with differing levels of success. There is a place in the clinic for an expert diagnostic questionnaire, I think, even if it is used to help you before you go in and see the patient to begin to think to yourself what you want to concentrate on when you do the case history.

Also, an expert case history device could be used by primary care providers to assist in the referral process. For example, an expert case history might point that professional to think that the patient might have BPPV. The primary care provider could conceivably do a Hallpike maneuver in the office, determine whether it is positive or negative, and then decide whether to try to manage it or send it to an audiologist for management. Lastly, expert questionnaires can have the potential to help begin to limit the number of possible diagnoses for a patient.

We recognize that dizziness can be caused by vestibular, neurological or cardiological disorders, to name a few. Unfortunately, the diagnosis often becomes the job of the primary care provider or emergency room physicians. We have to realize that patient descriptions can be unclear, inconsistent and sometimes unreliable. The physician must rely on history and a physical exam to determine what the next steps are going to be, and realize that when a correct diagnosis occurs, that there are often efficacious treatments that can help that dizzy patient or vertiginous patient.

The balance center at Washington University in St. Louis has used a clinical questionnaire consisting of about 163 items completed by the patient before their appointment. That 163-item questionnaire was used to identify some groups of items that contributed to the eventual diagnosis of that patient and to determine the power of sets of symptoms to distinguish between different diagnoses of dizziness. This is using information from the case history that has to do with symptoms to help narrow down the possible diagnoses.

The paper I’m reviewing today (Zhao, et al., 2011) was a retrospective review of 619 patients, with a mean age of about 57 years. In a neuro-dizzy clinic, you will typically see that the average age of your patient is about 57 years. It has been that way every place I have ever worked. The 163-item questionnaire took about an hour to complete, with 86 questions specific to dizziness and 77 questions relating to the review of symptoms and overall health complaints. The content areas of the questionnaire included a description of the dizzy spell and what it felt like, symptoms that suggested peripheral vestibular system impairment, symptoms suggesting central vestibular system impairment, auditory complaints and general physical and emotional health questions.

Some questions required yes/no answers while other questions were multiple choice. They narrowed it down to 47 items of the 163-item device that are answered yes/no for the most part. The link where you can find this questionnaire and download it is here: https://links.lww.com/MAO/A45

The final diagnoses for these 600-plus patients were BPPV for almost 27%, migraine-associated dizziness or migrainous vertigo in 16%, Meniere’s disease in 13%, vestibular neuritis in 8% and the rest were other diagnoses in broad classifications. They found that, in patients with BPPV, items that were positively correlated with that diagnosis of BPPV were items that contained statements about dizziness when lying down, position-dependent dizziness, and dizziness lasting several seconds. They found that items positively correlated with migraine-associated dizziness or migrainous vertigo had to do with light sensitivity, menstrual cycles, and the presence of severe recurring headaches.

The diagnosis of Meniere’s disease was positively correlated with auditory symptoms like unilateral hearing loss or unilateral tinnitus. Vestibular neuritis only correlated positively with nausea. They found that this 47-item device had an 80% sensitivity for the diagnoses of BPPV, migraine associated vertigo and Meniere’s disease. There was a 70% sensitivity for the diagnosis of vestibular neuritis. On average, this quantitative questionnaire was successful about 83.7% of the time.

They tried to further narrow the device down to 32 items, but found they could not do that and still maintain the device’s sensitivity. For adult patients, the predictive power of the questionnaire was good. The reason why it was good was that the three diagnoses had unique symptoms that helped differentiate them from other diagnoses.

It was not so sensitive for vestibular neuritis or for the detection of that diagnosis, likely because patients who have vestibular neuritis often have co-existing positional vertigo, so there are actually two diagnoses: vestibular neuritis and BPPV.

The merits of this questionnaire were the ability to render a hypothesis about what the final diagnosis was going to be for these patients, that it could be used in tandem with bedside tests, to begin to generate hypotheses that you then would prove or disapprove in the course of your assessment. It also potentially could be used by other healthcare providers in hopes of gating the flow of patients to specialists and subspecialists.

There are a few problems, however, with the questionnaire. First is that the diagnosis is not always correct, so you cannot look at it and use it as the gold standard. It might be used in an inappropriate manner, and it is critically dependent on the patient being an accurate historian. If the patient does not have good self-awareness or does not describe symptoms well, then the information they volunteer is not going to be that valid. The last thing that the authors suggested was that such a device could be used with computerized administration in the future, so this is something that could be done online.

Vanderbilt University Qualitative Dizziness Questionnaire (qDq)- First Attempt

Our attempt at developing a scale such as this was to take a large number of statements – I think we started with over 60 – and then statistically narrowed it down to 33 statements in 6 subscales. The subscales were migrainous vertigo, positional vertigo, Meniere’s syndrome, superior canal dehiscence, multisensory system impairment and chronic subjective dizziness.

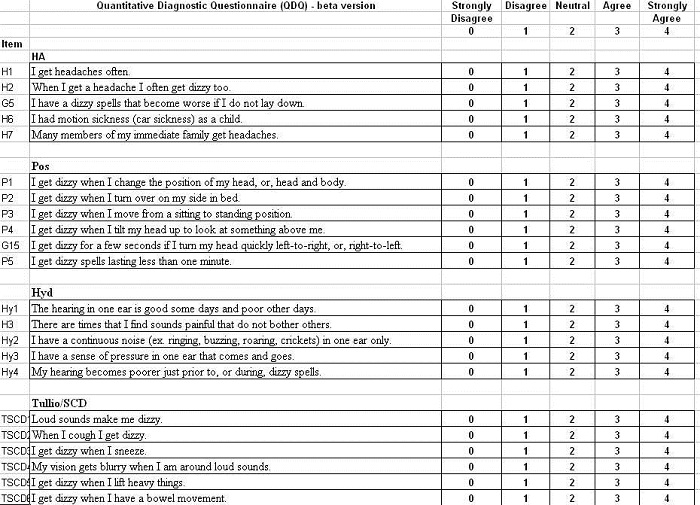

We took questions that comprised a case history and turned them into statements instead of questions. The patient had to then affirm on a scale of 0 to 4, with 0 being strongly disagree and 4 being strongly agree; 2 is a neutral response (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Draft of Vanderbilt University Qualitative Dizziness Questionnaire, which is in development.

Shown in Figure 3 are the items that comprised each of the subscales for headache, or migrainous vertigo, positional vertigo, hydrops, Tullio’s phenomenon and superior canal dehiscence, multisensory system impairment and chronic subjective dizziness. The patient answers each item and then we load the data into an Excel spreadsheet. What we are presented with is a histogram, showing the mean score for the scale – again, 0 to 4 – and then the various subscales along the bottom. At its simplest, the qDq provided a snapshot of what the patient’s primary complaint was, and possibly, their final diagnosis. Our suggestion is that a mean subscale score of 2.5 points or greater represents an endorsement of that subscale.

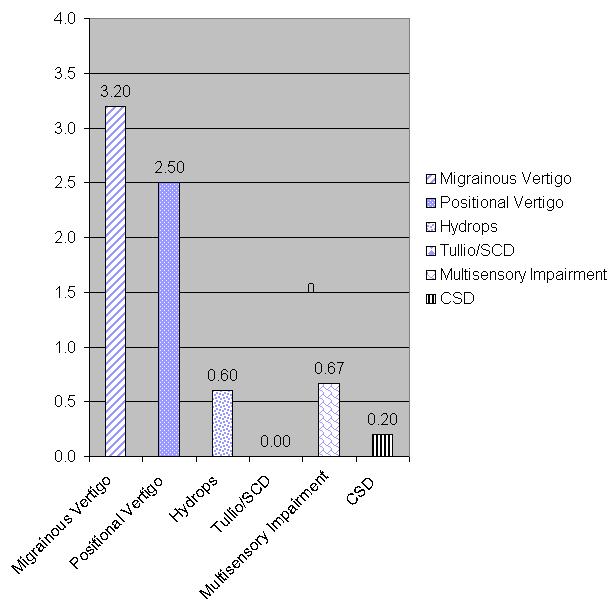

In this case (Figure 4), a patient had a final diagnosis of migrainous vertigo, showing an average score of 3.2. We use 2.5 as sort of an arbitrary cutoff; 2 was neutral, so 2.5 was heading towards a yes. So this person, no surprise, scored highest on the items in the migrainous vertigo subscale, and almost as high in the positional vertigo subscale. We know that patients who have migrainous vertigo also have positional vertigo.

Figure 4. Example of the scores for the different subscales of the qDq. Note that the highest socres are for migrainous vertigo, with positional vertigo also relatively high.

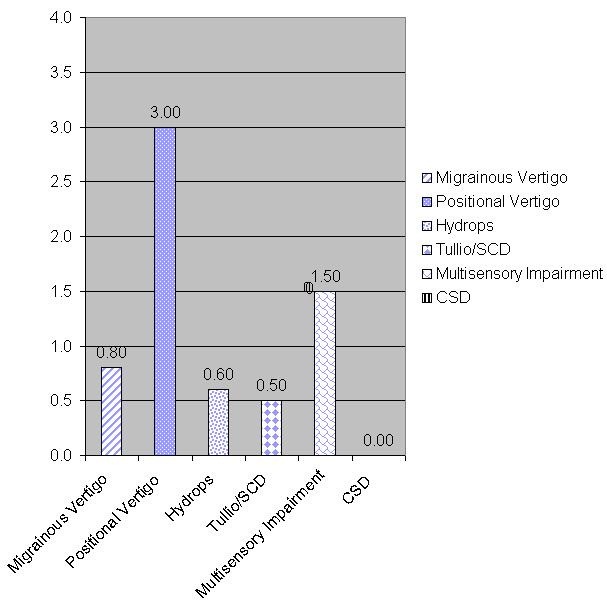

Another example is this patient with a diagnosis of BPPV, who scored an average of 3 points out of 4 on the positional vertigo subscale (Figure 5). Note that scores for the other subscales were quite low.

Figure 5. Patient with BPPV scoring high on the positional vertigo subscale.

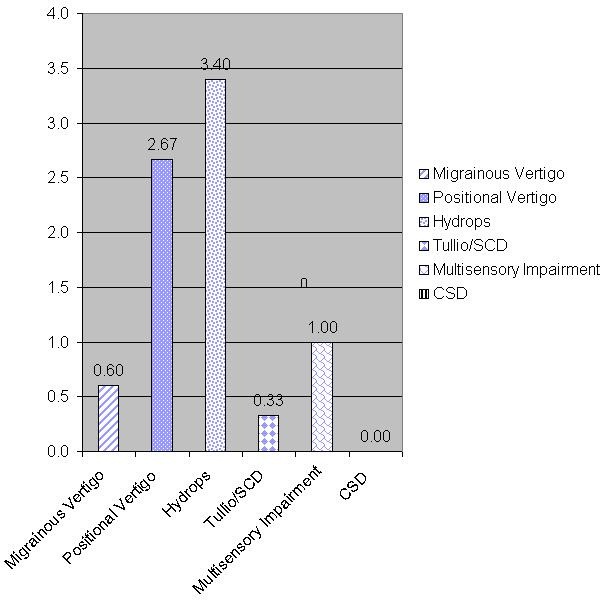

Figure 6 illustrates scores from a patient with Meniere’s disease who showed positive responses on the Meniere’s subscale. Again, it is not surprising that patients who have Meniere’s disease also experience positional vertigo as a function of the disease process. This is a patient (Figure 6) with chronic subjective dizziness who responded highest to those items, and also with positional vertigo. Positional vertigo seems to be something that affects most disorders and diseases. Furthermore, this is a patient with no vestibular system impairment whatsoever.

Figure 6. Scores from a patient diagnosed with Meniere’s disease.

Conclusion

In summary, today we’ve talked about three to four self-assessment measures that are quick to administer and provide the clinician with information that may be useful for the prediction of what will be the final diagnosis of patients with vertigo and dizziness. You can use the Mini-DHI for positional vertigo, the HADS for anxiety-related dizziness, the SIM-V for migrainous vertigo and the expert case history to assist in the final diagnosis of multiple diseases or disorders.

With that, I want to thank AudiologyOnline and Dr. Mueller again for the opportunity to present here, and to thank you for your attention today.

Question & Answer

If you could only do one questionnaire, what would it be?

Jacobson: That is a tough one. Of the ones that I discussed, I would probably go with a DHI, because if you get extremely high scores on the DHI, it is safe to predict that the patient will also have high scores on the HADS as well. The DHI is also so easy for people to complete. I do not get a lot of questions from patients saying, “What does this mean? I do not know how to complete it.” It is usually something that most all patients can do, so I would probably choose that one.

Mueller: Along those same lines, Gary, I know a lot of what you talked about centers around audiologists who are doing balance function testing. However, many audiologists do not do balance function testing in their practice. What do you think they should be doing if a patient reports dizziness? Should they be using one of the questionnaires you’ve described to determine who should be referred? Is that commonly done?

Jacobson: I do not think I would filter patients to be tested or not tested based on the result of an outcome measure. I think if the complaint of dizziness is bad enough to make somebody go see a healthcare professional, it means to me that they probably need to be evaluated. I always put that in the context of someone in my family. If someone in my family came to see me, and I was seeing them for audiometry for a hearing impairment and they mentioned that they were dizzy, would I refer them on if I did not routinely do the testing myself? I would. The complaint alone would be enough for a referral.

Which of the assessment questionnaires for hearing aids would you give or recommend?

Mueller: I guess that was directed to the little review that I did, and so I’ll jump in here. Time is always a concern, but a lot of questionnaires can be conducted before the patient arrives in the clinic, or they could be done in the waiting room with a technician or even a good receptionist or secretary administering them. It doesn’t necessarily have to use up the audiologist’s time.

I guess if you wanted to do something to give you a quick idea of the patient, I might go for something like the COAT, which samples 9 different areas. It would give you a quick review of their expectations, their real-world problems, their cosmetic issues, and it would give you a quick profile that actually might make some determination of what product you would go to in some cases, simply because it hits a lot of different areas. It is sort of like the IOI-HA, which is only 8 questions, but sometimes you need a quick screening test. So that might be a nice one to look at, and then you could follow-up with some of the longer ones. That would be my recommendation.

References

Baloh, R. W. & Honrubia, V. (2001). Clinical Neurophysiology of the Vestibular System. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, H. S., & Kimball, K. T. (2000). Development of the vestibular disorders activities of daily living scale. Archives of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, 126(7), 81-887.

Cox, R. M., & Alexander, G. C. (2000). Expectations about hearing aids and their relationship to fitting outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 11(7), 368-382.

Dillon, H., James, A., & Ginis, J. (1997). Client oriented scale of improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 8(1), 27-43.

Furman, J. M., Marcus, D. A., Balaban, C. D. (2003). Migrainous vertigo: development of a pathogenetic model and structured diagnostic interview. Current Opinion in Neurology, 16(1), 5-13.

Jacobson, G. P. (2012, January 23). HASP self-assessment inventory. Audiology Online, Ask the Expert. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com/ask-the-experts/hasp-self-assessment-inventory-13

Jacobson, G. P., Newman, C. W. (1990). The development of the dizziness handicap inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, 116(4), 424-427.

Jacobson, G. P., Newman, C. W. Fabry, D. A., & Sandridge, S. A. (2001). Development of the three-clinic hearing aid selection profile (HASP). Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 12(3), 128-141.

Jacobson, G. P., Ramadan, N. M., Aggarwal, S. K., & Newman, C. W. (1994). The Henry Ford Hospital headache disability inventory (HDI). Neurology, 44(5), 837-842.

Marcus, D. A., Kapelewski, C, Rudy, T. E., Jacob, R. G., & Furman, J. M. (2004). Diagnosis of migrainous vertigo: validity of a structured interview. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and clinical Research, 10(5), CR197-CR201.

Mueller, H. G., & Palmer, C. V. (1998). The profile of aided loudness: A new “PAL” for ’98. The Hearing Journal, 51(1), 10, 12-19.

Neuhauser, H., Leopold, M., von Brevern, M., Arnold, G., & Lempert, T. (2001). The interrelations of migraine, vertigo, and migrainous vertigo. Neurology, 56(4), 436-431.

Newman, C. W., Jacobson, G. P., & Spitzer, J. B. (1996). Development of the tinnitus handicap inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, 122(2), 143-148.

Newman, C. W., Weinstein, B. E., Jacobson, G. P., & Hug, G. A. (1990). The hearing handicap inventory for adults: psychometric adequacy and audiometric correlates. Ear and Hearing, 11(6), 430-433.

Powell, L. E. & Myers, A. M. (1995). The Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 50A(1), M28-34.

Sandridge, S. A., & Newman, C. W. (2006, March 6). Improving the efficiency and accountability of the hearing aid selection process- use of the COAT. AudiologyOnline, Article 1541. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/improving-efficiency-and-accountability-hearing-995

Staab, J. P., & Ruckenstein, M. J. (2003). Which comes first? Psychogenic dizziness versus otogenic anxiety. Larygnoscope, 113(10), 1714-1718.

Ventry, I. M., & Weinsten, B. E. (1982). The hearing handicap inventory for the elderly: a new tool. Ear and Hearing, 3(3), 128-134.

Whitney, S. L., Marchetti, G. F., & Morris, L. O. (2005). Usefulness of the dizziness handicap inventory in the screening for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otology & Neurotology, 26, 1027-1033.

Yardley, L., & Putman, J. (1992). Quantitative analysis of factors contributing to handicap and distress in vertiginous patients: a questionnaire study. Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences, 17(3), 231-236.

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia, 67(6), 361-370.

Cite this content as:

Jacobson, G. (2013, February). Vanderbilt audiology journal club: Assessing dizziness and vertigo - helpful self-report measures. AudiologyOnline, Article #11567. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com/