Verbal communication, along with opposable thumbs, separates humans from the rest of the animal kingdom. When communication is compromised due to the loss of hearing, which is a common problem associated with the aging process, individuals often seek the care and guidance of professionals. Audiologists (and hearing instruments specialists) are uniquely equipped to help individuals suffering from the effects of hearing impairment by offering customizable hearing aids fittings as well as expert care and support. These offerings, which are usually comprised of the labor-intensive process of tailoring a pair of devices to the impaired auditory system, plus patient counseling and guidance in the process of overcoming the effects of diminished communication as individuals age, has significant value.

Additionally, because this comprehensive set of offerings has intrinsic value and its price is largely determined by market forces and next-best alternatives, such as over-the-counter personal sound amplification products, surgically implantable devices or the patient deciding to do nothing, it must be priced carefully.

Since effective communication relies on hearing, shouldn’t the professionals who provide improved hearing to millions of individuals be compensated accordingly? Just as verbal communication and opposable thumbs separate humans from other animals, unique services offered by audiologists separate the profession from other competitors, and must, therefore, be priced appropriately. This article will examine how practitioners can unlock value in their offerings to individuals suffering from the long-term effects of hearing loss using a value-based pricing strategy.

Confessions of an Over-discounter

Allow me to share my story as it relates to hearing aid pricing. There was a time early in my career when I thought lowering the price on the hearing aids I dispensed would lead to more sales. In order to gain agreement from patients I found myself lowering the price on a specific technology tier or advising the patient to downgrade to a less expensive technology, rather than defend the value of my recommendation. As I have come to learn, hearing aids and their associated services exist in a largely inelastic market, where lowering the price does not translate into greater volumes of business. After reading further, I hope you do not repeat many of my mistakes.

Your journey to better understanding how pricing and value affect the dispensing of hearing aids can start with some late night television viewing. To appreciate how price strategy and communication of price to consumers affects buying habits, spend some time watching the Home Shopping Network. Like many viewers, you may become mesmerized by all the fantastic deals that are just a phone call away. After all, who can’t use one of those gadgets that cooks your entire meal in three minutes? It might seem crass, but audiologists can learn a thing or two about how they price their products by watching these infomercials. The legendary Ron Popeil of Ronco was the master of anchoring a high price point, demonstrating all of the cool features of a product, reframing the product at a lower price to create a “wow” effect, and then restating an offer with value-added extras at a lower price. Even though audiology is a medically-oriented profession, we oftentimes have to ask people to pay large sums of money out-of-pocket for something they do not want. As you will learn in this article, even though we offer a service, Ron Popeil offers beneficial insights about how to communicate price and value.

Effectively Communicating Price and Value

Before getting into the specifics of value-based pricing strategy, let’s spend some time analyzing the communication methods of Ron Popeil and the Home Shopping Network. What exactly is it that Ron Popeil of Ronco has done to put items such as rotisserie ovens, the pocket fisherman and food dehydrators in millions of homes around the country? The simple answer is effective communication about value and price. Specifically, there are three pricing tactics pioneered by Popeil and mastered by infomercial producers for decades: framing, anchoring, and default bias. These tactics can be readily applied to the communication of price and value as they relate to hearing aids and their associated services. Regardless of the pricing strategy you use in your practice (as you will learn, there are three possible strategies), practitioners would be wise to adopt Popeil’s communication methods when discussing price and value with patients.

Framing

The context in which a price is communicated to a customer affects how much the customer may be willing to pay for something. When Popeil mentions alternatives to his product that are available at higher price points, this is an example of framing. In the hearing aid market, audiologists could frame their offerings by demonstrating key features relative to potential alternatives that cost considerably more. For example, once the likely long-term consequences of doing nothing about hearing loss is shared with the patient, it helps frame the benefits of a pair of professionally-fitted hearing aids.

Another example of framing is the use of bundling (or unbundling) your offerings. When many of the key technology and service features are itemized and a dollar value is assigned to each, it frames your offering much differently than if you were to simply list one price in a bundled format. Research has shown that unbundling results in many patients willing to pay more for the same offering (Amlani & Taylor, 2012). The tactics of bundling and unbundling price is important to audiologists and will receive more attention later in this article.

Anchoring

Consumers typically have a good idea of the price of products and services that they purchase on a routine basis. For items you buy regularly (e.g., turkey on Thanksgiving, a new laptop computer, a gallon of milk, a tank of gasoline for your car) you expect to pay a certain amount. The price you expect to pay for a product or service is an anchor. Price anchors are mainly determined by your experience buying a particular product, and they can change based on the season, time of day or even economic conditions. For example, if you see a low price for an iPad in a newspaper coupon with an expiration date for tomorrow, you may make a special trip to the Apple store to buy it now – even if you do not really need a new iPad.

Anchoring is one reason why sales work so well. Based on previous buying experience, customers know they are receiving a “good deal” when a special low sale price is spotted in a newspaper ad or coupon. The challenge associated with respect to anchoring in the hearing aid market is that the average consumer is not very familiar with the time and expertise usually required to successfully fit hearing aids. When a dispensing practice runs advertising using low price points to drive traffic, an unintended consequence is anchoring a low price point in the mind of the prospective buyer. Once a price has been anchored in the mind of the customer it is difficult to change it.

Popeil is remarkably effective at anchoring a relatively high price for a product, demonstrating all the features and benefits of his product compared to the anchor, and then offering his product at a lower price. Audiologists would be prudent to anchor a high price, such as a deeply inserted device (e.g., Lyric) and then discuss features and benefits of their offering relative to the higher priced anchor.

Default Bias

Consumers generally take a path of least resistance when making purchases; some might call this laziness or inertia. Default bias is the term used to describe this path. When an obstacle - even one as simple as checking a box to become eligible for a service or upgrade - is placed in front of a customer, they oftentimes do not voluntarily opt to buy it. An example of the role that default bias plays in markets is that of organ donations. States that changed their organ donation system from one in which individuals had to opt into the organ donation program by checking a box on their driver’s license renewal to one in which they were are automatically enrolled in the program saw the number of organ donation volunteers more than double. Another, perhaps less morbid example of default bias is 401k retirement plans. Typically, employers make 401k retirement plans something their employees can opt into. When this is the default option upwards of 50% of employees do nothing and, therefore, opt out of the voluntary retirement plan. However, when the employer makes automatic enrollment the default option, very few employees voluntarily opt out of the program.

Popeil makes it easy for customers to make buying decisions by effectively using default bias. By bundling several smaller items into an offering, Ronco uses default bias to enhance the value of their offerings. The lesson for audiologists with respect to default bias is that items that are necessary for the success of the patient need to be included in the price. Later in this article the use of itemized bundling will be covered, which is an example of default bias.

Overarching Questions about Price and Value

Let’s continue our discussion of price and value by asking ourselves a couple of critical, overarching questions that will help set the stage for pricing strategy. These questions should be on the top of your mind when implementing your pricing strategy because the exact answer is highly dependent on your market, the competition and how you differentiate your practice. Your thoughtful responses to these three overarching questions will help you determine your “go-to-market” pricing strategy.

- How do patients in your market benefit from your “product?” The word product is in quotation marks here because it represents both the devices and the service you deliver to ensure that the devices are optimized to the patient’s needs and expectations. A large part of your "product" is your brand or reputation.

- How is your “product” different than the competitor’s next-best alternative? Next-best alternatives not only include those of competitors, but also devices sold on the Internet, apps downloaded to smartphones, and surgically-implanted devices.

- Does your clinic look and feel like a place where someone would willingly spend more than $5,000? Customers intuitively know that high price is a signal for high quality. Therefore, everything about your office needs to exude quality if you want to charge high prices.

Your responses to these questions require a deep dive into the values and mission of your practice. No two practices will answer them in the same way, and your answers will form the foundation for a value-based pricing strategy in your clinic. Of course, you can expect the answers to the first two questions to be related to the devices you offer your patients, typically tiered along levels of technology varying by certain key features. In addition to the ubiquitous hearing aid device, there are several other attributes that patients are willing to pay for. These include personalized service, prompt attention, expert guidance, peace of mind as a result of improved communication, ease of use, simplicity and professional experience. Your task is to first construct a list of attributes that are unique to your practice relative to next-best alternatives.

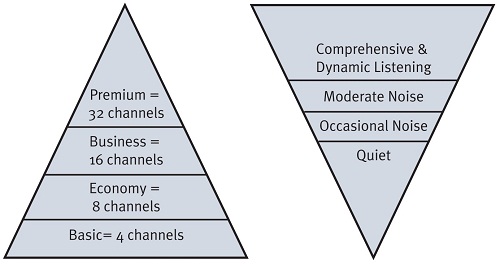

Currently, most differentiation across practices and tiering of value is done almost exclusively with the device itself. Since the beginning of the digital signal processing era nearly 20 years ago, differentiation has been based on number of channels of wide dynamic range compression (WDRC). Not only is differentiation across technology based on channels lacking sufficient evidence (no more than 8 to 16 are needed to optimize audibility and sound quality), it ignores several other attributes that patients may value. Figure 1 contrasts two different ways of thinking about product value. The pyramid on the left represents the traditional tiering of technology using channels of WDRC, while the pyramid on the right depicts a more comprehensive method, incorporating other attributes that hearing-impaired customers and their families are more likely to value, such as listening in ever-changing, dynamic environments.

Figure 1. Using a customer-attribute tier (right) rather than a traditional channel-based tier (left) requires audiologists to broaden their thinking about how customers approach the market for hearing services.

The Fundamentals of Supply and Demand

Before getting into the details of value-based pricing strategy, it is helpful to understand how the economic laws of supply and demand affect price. A simple example of how changes in supply and demand affect price can be found on a rainy day in New York City. Imagine you are attempting to walk from Times Square to Greenwich Village. As it begins to rain, you realize you do not have enough money for a taxi and you do not have time to navigate the gnarly New York City subway system. Since your only choice is to walk without getting soaked, you spot the nearest street vendor with umbrellas for sale. As you approach his stand, you notice that he has raised the price of his umbrellas by $5 from the price you noted earlier in the day when the sun was still shining. Since you do not want to get wet, his doubling of the umbrella price to $10 still seems like a pretty good deal and you reluctantly buy one.

To fully appreciate the laws of supply and demand and their relationship to price, let’s examine this scenario in two different ways. In the first scenario, let’s say that the umbrella industry has lobbied the government to effectively restrict the number of licensed vendors who are able to sell umbrellas. The result of their lobbying efforts is that there are a limited number of vendors selling umbrellas (one vendor every 15 city blocks). This government action keeps the supply of umbrellas artificially low and, thus, the price relatively high. Restricting the number of vendors effectively keeps the competitors at bay, but it does not make all the rain-soaked customers very happy, as they either put up with paying the higher umbrella prices or seek out alternatives, such as using an old newspaper to cover their heads or a more expensive raincoat that is cumbersome to pack and use when rain starts to pour.

Now, let’s look at umbrella usage in a free market system where the high prices of umbrellas on a rainy day create incentives for entrepreneurs to enter the market and offer umbrellas at lower prices. In the free market system, high prices are a signal to entrepreneurs that profits can be made by offering a next-best alternative at a lower price. Entrepreneurs who fail to compete with lower prices or a higher-quality alternative that is priced higher are likely to be driven out of business. Of course, the customer ultimately wins in the free market scenario because he has a range of choices as he walks through Manhattan on that rainy day. He can buy a really cheap umbrella that lasts for one day or one that is of much higher quality for more money that will last a lifetime. The free market system represents greater choices for customers as well as increased opportunities for entrepreneurs to creatively address the needs of customers with unique product and service offerings. Value-based pricing strategies represent a method of unlocking these opportunities for both customers and entrepreneurs who serve the market. As you will read shortly, this holds true in the market for hearing aids and associated services.

The economists Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok of George Mason University have coined the phrase “price is a signal wrapped in an incentive” to describe how pricing works in the real world (Cowen & Tabarrok, 2011). In the umbrella scenario, price is a signal to customers and entrepreneurs alike. In a free market system, price signals to entrepreneurs that profit opportunities exist, and for customers it signals a choice of various products. In addition to sending a signal, prices create incentives for customers to buy. As you will learn, a value-based pricing strategy is predicated on your ability to recognize what various segments of your market find appealing about your offering, and creating incentives for those customers to purchase from you.

In many ways, your role as service provider is to make price irrelevant to the patient. This involves your ability to transform the quality of the patient’s life through the customization of medical devices. The prices you charge for this transformation is your signal to the market. The engaging clinical experience you provide individuals to make this transformation is the incentive for patients to do business with you.

Pricing Strategies (Think Like an Accountant or a Customer?)

Any low volume, high margin business like hearing aid dispensing requires careful attention to how retail prices are signaled to the market. Traditionally, most practices use either a simple mark-up or margin-based pricing strategy. Both of these strategies require you to think like an accountant. The simpler of the two is a mark-up strategy. With a simple mark-up strategy, the manager applies a multiplier to the wholesale cost to obtain the retail cost. For example, if your mark-up is 100%, the wholesale cost is multiplied by two (x2) to get the retail price. In a purely mark-up based strategy, the wholesale cost is “marked up” without regard to breakeven point or gross profit requirements.

A margin-based pricing strategy is slightly more sophisticated, however, as more attention is paid to keeping the whole cost-of-goods of all products in alignment with the cost of running the business. In a purely margin-based pricing strategy, the manager determines the cost-of-goods required to maintain a specific gross profit that is needed to maintain a sustainable business.

A margin-based pricing strategy is dependent on the practice manager doing some break-even cost evaluations to ensure that they are charging enough to cover costs and make a marginal profit so they can stay in business. Both the margin-based and simple mark-up strategies lack a detailed analysis on what attributes are desired by different segments of the market, and how prices can be presented to unlock that value across various customer segments. This is what a value-based strategy brings to the table.

The Three Types of Pricing Strategies

o Simple Mark-up: Multiply the invoice cost by a set amount (e.g., x3)

o Margin-based: Involve your accountant before multiplying the invoice cost

o Value-based: Involve your customers and find out what they value in your offerings

Value-based Pricing Strategy

The key to understanding value-based pricing is thinking like a customer. Since all of us buy things just about every day, it should not be too difficult. The attributes of the products and services we buy largely determine their value. This forms the basis for value-based pricing. Characteristics such as price, convenience, performance and simplicity determine how much customers are willing to pay for something. The more we value a certain attribute (and the harder it is to find reasonable next-best alternatives) the more we are willing to pay for it. Value-based pricing is used to sell multiple offerings at multiple prices by identifying the key attributes customers are willing to pay more or less for. According to Mohammed (2010), value-based pricing can be used to signal quality in your marketplace when this five-step process is orchestrated:

- Identifying target customers

- Identifying their next-best alternatives

- Determining your offerings’ differences

- Calculating your offerings’ value based on its differentiation

- Making sure your pricing is competitive

A quick example might help you better understand value-based pricing strategy using this 5-step process. Let’s say that you have a 1973 Porsche convertible. It is a relatively rare car in mint condition. Mohammed’s (2010) 5 steps can be used to determine your asking price. First, you might spend some time carefully identifying your target market. After doing so, you make the decision to advertise on websites that cater to men over the age of 50 because you believe this segment of the population finds vintage cars appealing and would have the discretionary income to buy one. Second, you would evaluate the next-best alternatives on the market. In this example, next-best alternatives might include new sports cars and other similar vintage sports coupes listed on Craig’s List. Third, you would determine the attributes of the car that are unusual, rare or highly valued by certain segments of your market. In the case of the Porsche, this would be that it is a convertible and it is a hard-to-find red color. Because these attributes are rare, you will be able to charge more for them. Fourth, you would calculate the asking price based on these differences relative to the results of steps two and three. Maybe you have found that people are willing to pay an extra 25% for vintage convertible roadsters. This allows you to price the car at a higher price with the confidence that there is a pool of interested buyers ready to hand you a certified bank check. Finally, after you have established a price for the car, you do some double checking to make sure your price is in line with comparable cars that are on the market. For example, if your preliminary price is several hundred dollars higher than the next highest price, you may consider dropping your asking price slightly.

Notice that a true value-based pricing strategy, like the example above, is not a simple mark-up of the wholesale price or based on a margin percent. Rather, a value-based strategy in its purest form relies on the seller to carefully calibrate the needs of the market and the attributes of the product to determine the asking price. The 5-step value-based pricing strategy above works well for selling one product in relatively high demand, but can the strategy be effectively employed with hearing aids? When following some reality-based guidelines with a few modifications, value-based pricing can be used to establish retail prices in your clinic. Of course, you are not selling a vintage sports coupe, but by pricing your expertise and services accordingly, you can successfully differentiate your offerings.

Before we tackle a value-based pricing strategy for an audiology practice, however, let’s spend time reviewing some of the nuances of the hearing aid dispensing business that make it different than selling a vintage Porsche. The hearing aid dispensing market is unique for a number of reasons, and each must be taken into consideration when adapting a value-based pricing strategy.

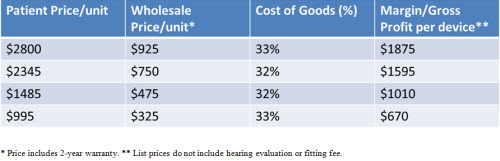

First, because they are a relatively small number of buyers for hearing aid services compared to other products, practitioners must maintain relatively high margins in order to make a profit and stay in business. Brady (2010) uses a concept called the “Rule of Thirds” to calculate the cost-of-goods (COG) and gross profit needed to cover expenses and make a before-tax profit. Using Brady’s rule, the cost-of-goods needs to be around 30% to 35% of the retail cost of the offering to each patient. Maintaining this COG range requires practitioners to be strong negotiators with their vendor partners and to thoroughly evaluate the retail price charged to patients.

Next, lowering prices does not increase total volume of hearing aid sales. Amlani (2009) indicated that lowering the retail price does not have an appreciable effect on demand. This suggests that the hearing aid market is relatively inelastic, as hearing aid demand does not change for prices between $500 to $3000 per unit. As the provocative title of Amlani’s 2009 article suggests, practitioners are not immoral when they raise their prices. Thus, they must look for ways to build value into their offerings, while maintaining a high average selling price.

Third, MarkeTrak survey data (Kochkin, 2007) indicates that approximately one-third of hearing aid purchases are reimbursed or covered by third-party payers. Depending on the patient’s specific medical plan, 100% of the costs are covered or partially covered. Partial coverage of hearing aids represents a partial incentive, as the patient is required to pay the difference out-of-pocket if he or she wants to upgrade.

Ramachandran and colleagues’ work suggests that these partial incentives do not motivate customers to buy (Ramachandran, Stach, & Becker, 2011). In their study, they evaluated the product level, age of acquisition and degree of hearing loss of three groups: full coverage of hearing aids, partial coverage of hearing aids and out-of-pocket private pay. Their findings showed that full insurance coverage lowered the age of acquisition and attracted patients with milder hearing loss, whereas partial coverage did not. Moreover, their findings indicated that those with partial coverage were less likely to upgrade to higher levels of technology or wear a bilateral hearing aid arrangement relative to both the full coverage and private pay cohorts. This study indicates to practitioners that partial coverage does not incentivize many patients to upgrade by paying the out-of-pocket difference. It also indicates that there is a relatively strong private pay market for mid-level and premium offerings. This suggests that, for many practices, there is a private pay market segment and an insurance-based market segment that each have a different set of expectations.

Fourth, as previously mentioned, how you communicate (or signal) price to the market influences a customer’s willingness to pay for an offering. This concept is known as framing. When features are unbundled and assigned a dollar value, customers are willing to pay more than when the offering components are bundled together and sold as one flat price. Amlani and colleagues (2011) showed three groups of retired adults three different hearing aid advertisements. All groups were shown the same hearing aid, but each of the three ads had a different written message accompanying it. Group 1 was shown an ad with very little information pertaining to features, Group 2 was shown a feature-laden ad, while Group 3 was shown an ad that listed several potential benefits using non-technical terms. The ads shown to Groups 2 and 3 are examples of unbundling or itemizing, as key features and benefits are listed as individual bullet points. Results indicated that patients who were shown the unbundled messages were willing to pay slightly more for the same device. Furthermore, the results indicated that experienced hearing aid users were willing to pay more when technical benefits were unbundled, while inexperienced hearing aid users were willing to pay more when non-technical, service-oriented features were unbundled and assigned an individual dollar value. This research is an example of the effects of framing and its impact on a customer’s willingness to pay. That is, when features and benefits are itemized you are framing them so that the perceived value of various items are increased.

What Attributes do Customers Value the Most?

This section will provide practitioners with a template for implementing a customized version of a value-based pricing strategy for their own clinic. First, let’s briefly examine a topic of relatively recent interest, which is the unbundling of prices.

As a general rule, practitioners in the hearing aid industry have traditionally bundled their offerings to consumers. This means that several features and services are combined (or bundled) and offered to patients at a single price point. For example, the practitioner might bundle the hearing evaluation, hearing aid fitting fee, hearing aid and warranty into one single unit price. The chief advantage of bundling is simplicity. Because patients are given a single price with several benefits wrapped into one flat fee, it is believed that customers are more apt to make a purchasing decision (Tjan, 2010).

Over the past few years, unbundling has gained popularity among practitioners, especially those in private practice. In an unbundling format, many of the key attributes of the offering are itemized and a dollar value is assigned for each of them. For the consumer, unbundling offers them an à la carte selection of product and services offerings. For the practitioner, unbundling has the potential to increase revenue for various clinic procedures that otherwise may have been bundled into the price of the hearing aid itself. Unbundling has likely become a more popular strategy by practitioners because more third party insurers are able to reimburse for various procedures that are completed during the hearing aid selection and fitting process.

Additionally, Sjoblad and Warren (2011) have suggested that unbundling allows practices an opportunity to show the value of various clinical procedures by assigning a dollar value to each of them. Although unbundling represents greater potential revenue opportunities for practice owners, experts suggest that it allows customers an opportunity to negotiate for services that are a necessary component of their comprehensive care (Tjan, 2010). Although no studies have directly compared the revenue generated using an unbundled versus a bundled pricing model, anecdotal evidence suggests that a purely unbundled pricing model leads to greater generation of revenue from testing, but also leads to more haggling over some of the necessary components of long-term patient care. Perhaps a balance is needed between the benefits of unbundling and bundling offerings that benefit the long-term care needs of the patient with the revenue needs of the practice.

In order to balance the needs of patients to receive a high quality service experience with those of a sustainable practice, a hybrid approach to pricing that takes the best elements of both the unbundled and bundled models should be considered. For practices looking to optimize revenue while maintaining high standards of comprehensive patient care, the following 4-step, value-based pricing strategy is proposed.

1. Cost and margin analysis. Using the principles put forth by Coverstone (2012), Brady (2010) and Sjoblad and Warren (2011), practices must carefully evaluate their current cost of goods, fixed and variable costs as well as breakeven points. This requires a detailed analysis of current cost of goods and gross profit for each hearing aid dispensed over the past year. Once current costs and margins are understood, the practice must work to bring the cost of goods to between 30% and 35% across all technology tiers. Figure 2 is an example of how the cost of goods and gross profit look under such a tiered system. Note there are four price points in this simplified tiered approach and the gross profit margin (retail price – cost-of-goods) is known across four tiers.

Figure 2. An example of tiered pricing strategy following analysis of cost-of-goods for a hypothetical practice.

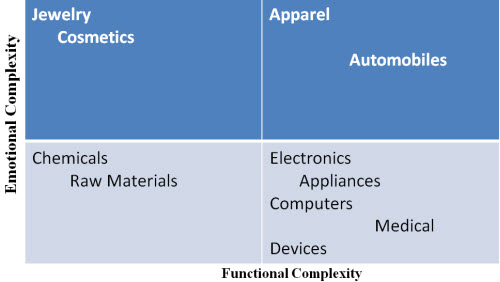

2. Obtain customer feedback. The second step requires that practices use the best available data to construct a simple demand curve. In larger corporations a demand curve is constructed using sophisticated market research analysis in order to evaluate the demand for particular products and features at various price points. Ulwick (2005) charted various products on a 4-quadrant matrix based on emotional and functional complexity. Figure 3 shows that medical devices are rated solidly in the functional complexity category. Ulwick’s work implies that the tiering of hearing aid technology should be based on functional complexity. That is, as the functionality becomes more sophisticated, the price increases. The common practice of tiering hearing aid technology based purely on number of channels does not fully leverage Ulwick’s model.

Figure 3. Functional vs. Emotional Complexity.

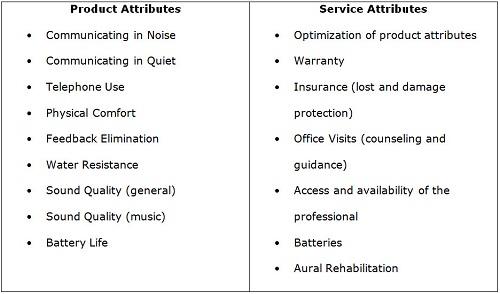

For the typical hearing aid dispensing practice, the type of data needed to construct a demand curve is not readily available. The good news, however, is that practices can rely on simpler methods to prioritize the buying preferences and attributes for which customers are willing to pay. You can begin this process by creating a list of product attributes and service attributes that the average hearing impairment patient desires, like the one shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. A partial list of common audiology/hearing aid attributes. Readers are encouraged to expand this list.

Once you have established a list of attributes, the next task is to prioritize the list. Research can be used to make some data-driven decisions on the rank order of these attributes. Both MarkeTrak VII (Kochkin, 2007) and Bridges and colleagues (2012) indicated that performance in background noise is the primary product attribute sought by hearing aid users. This was followed by improved sound quality, feedback reduction and comfort. Knowledge of the chief attributes sought by hearing aid users can be used in creating your value-based pricing system. Figure 5 illustrates product attributes (designated by listening situations) and the corresponding levels of technology best suited for those situations. As Figure 5 suggests, as you move up the tiers, the attributes that are most important for the buyer increase in technological sophistication. One challenge associated with tiering hearing aid technology is that several of the most valuable features are available at many technology levels. This makes it difficult to tier exclusively on product features.

The tiering of hearing aid prices based on technical attributes is geared mainly toward experienced users of amplification. As Amlani et al. (2011) suggested, inexperienced hearing aid users are likely to value many of the non-technical attributes, such as service and warranty. This represents an opportunity to tier service attributes as well. Performance in background noise, automatic and wireless features, and various levels of warranty and service represent some of the opportunities to tier value at three to four distinct price points.

In addition to the product attributes summarized in Figure 5, there are several other attributes associated with the personal service business model that must be part of any value-based pricing strategy, many of which are listed in Figure 4.

Figure 5. Customer attributes (designated by listening situations) and the corresponding levels of technology best suited for the patient.

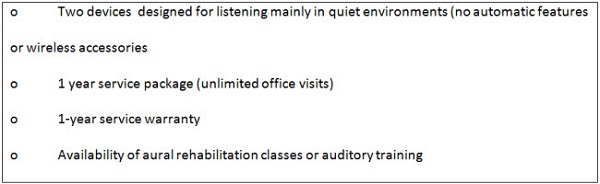

3. Tier attributes at specific price points. Once you have done the preliminary work of evaluating margins and costs and you have obtained some voice-of-customer information about attributes that are most valued, it is time to formalize your go-to-market offerings at three or four tiered prices. For instructional purposes, let’s say our hypothetical practice has decided to create three distinct offerings at three price points - $2,500, $3,500 and $5,000. The first step is to establish your baseline or entry-level offering by asking yourself, “What is the minimum technology and service offering I am willing to provide all of my patients?” For example, your margin and cost analysis indicates that you can profitably provide to the market a $2,500 entry level offer. What features and services do you provide at this price point? Figure 6 shows an example of features and benefits that can be offered at an entry-level price of $2500. Using the concept of default bias we have intentionally packaged a pair of hearing aids plus warranty and service into a one-year program, as most professionals would agree that this is a reasonably good starting point for meeting the objectives of optimizing benefit in relatively quiet listening places.

Figure 6. Example of baseline “Quiet Listening” package.

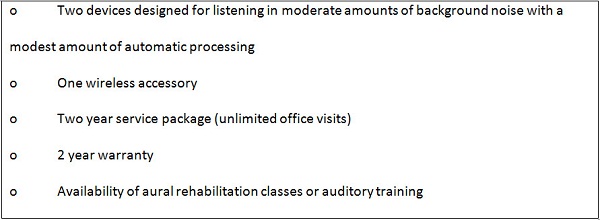

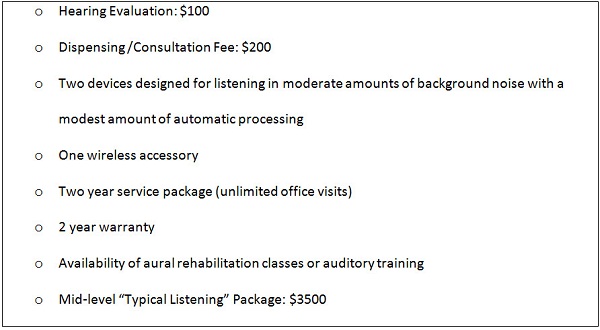

Once you have established your baseline tier or package, the next step is to devise one or two additional tiers that will comprise your mid-level offerings. In the mid-level tiers, the attributes that are typically valued the most by customers, such as more sophisticated technology for hearing in background noise, automatic features and more comprehensive or longer service packages, are built into the offerings. Figure 7 represents an example of a mid-level offering. The critical question that you need to address would be, “Is this offering worth an additional $1000 to the patient?”

Figure 7. Mid-level “Typical Listening” package.

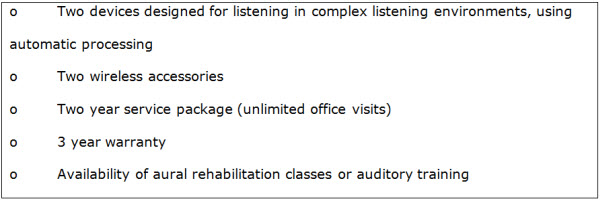

The final step is to create a premium offering at the highest price point. This can be done by adding the attributes valued most by the most demanding customers. Figure 8 is an example of value-added attributes at the premium level. As you create the premium package, the critical issue is ensuring that it has a perceived value to the patient of an additional $1500 relative to the mid-level offering.

Figure 8. Premium “Dynamic Listening” package.

The goal of creating tiers or packages at three or four specific price points is to strike a balance between a relatively limited number of choices to the customers and offering a number of attributes valued the most by customers. This value-based approach is a hybrid that takes the advantages of both a bundled and unbundled strategy. This approach is known as versioning (Mohammed, 2010) because it combines several attributes into three or four packages that customers can choose from.

4. Signal to the market with itemized bundles. The compromise between purely unbundled and bundled offerings is best described as an itemized bundling approach since it attempts to combine advantages from an itemized approach and a bundled approach. In an itemized bundle approach, practitioners are able to unbundle the necessary testing procedures that need to be completed on each patient prior to purchasing hearing aids. These unbundled items would typically have a CPT code associated with them. Unbundling these required procedures shows the value of these essential diagnostic procedures, while bundling all other components of offerings across three or four tiers gives the patient some simple choices (versions) to choose from. Using itemized bundles makes it unlikely that customers will haggle over necessary components of the offering because they have been bundled into the price (Tjan, 2010) and allows you to create offerings that you know will be most effective for treating their hearing loss (default bias). An example of an itemized bundle is shown in Figure 9 for a mid-level offering. Note that the patient is responsible for paying the dispensing and evaluation fee, but the rest of the offering is bundled together. The $100 hearing evaluation fee and the $200 consultation fee could be submitted to a third-party payer for reimbursement or paid by the patient out-of-pocket. The total cost for the itemized bundle shown in Figure 9 is $3800 for this hypothetical practice.

Figure 9. An example of an itemized bundle with three separate fees.

Using itemized bundles, like the example shown in Figure 9, enables practices to strike a balance between value and simplicity. By unbundling the pre-fitting procedures, practices are able to demarcate their value for specific test procedures needed to identify type and degree of hearing loss, while also obtaining reimbursement from third-party payers when possible. At the same time, bundling many of the features required for a successful fitting keeps the number of patient choices at a manageable level, and incentivizes patients to move up to a more sophisticated technology/service package.

In addition to the itemized bundle “versioning” strategy, there are two other value-based pricing strategy tactics outlined by Mohammed (2010) that may have utility in a hearing aid dispensing practice, pick-a-plan and differential pricing. Both can be employed in situations in which one of the itemized bundles is not needed or wanted by the patient.

Pick-a-Plan

Internet distributors and third-party payers oftentimes enable practitioners to collect a professional fitting fee for their service time. From a value-based price strategy perspective, this represents a pick-a-plan tactic. Although perhaps not as profitable to the business, using a pick-a-plan tactic can attract a different segment of the hearing aid market to your practice that you ordinarily would not see in a personalized service business: the price-conscious shopper. For example, offering a separate “service fee” for patients purchasing hearing aids online is an alternative revenue stream for the practice, and attracts another segment of the market to your practice. A pick-a-plan strategy can also be used for patients desiring a unilateral fitting, as they could be offered one hearing aid at a higher retail cost than if it were packaged as part of a bilateral, itemized bundle.

Differential Pricing

The use of coupons, club memberships and subscriptions are examples of differential pricing tactics (Mohammed, 2010). Differential pricing can be used to bridge the gaps between itemized bundles, discussed previously, and accessories that might be needed by a particular patient. For example, a practice could create an à la carte menu of items such as assistive devices, wireless accessories and sundry items that are offered to patients. If an individual decided to purchase the “Quiet Listening” bundle but really needed an assistive device for television viewing, they could be guided to purchasing something off the à la carte menu. Differential pricing tactics can also be employed for capturing business from the public assistance market. Depending on the funding source, practices can use differential pricing tactics to create incentives to this government-regulated segment of the market by offering very basic digital technology - not offered in any of the itemized bundles - at a low price point.

High Price Signals High Quality

If price is a signal your practice sends to the market, then given the high price points paid out-of-pocket relative to other offerings in the healthcare arena, hearing care professionals are definitely sending a signal of high quality. The essential question is, “Does my practice exude high quality and look like a place where people would be willing to spend more than $5,000?” It is only through the foundation of a culture devoted to continuous improvement, judicious use of clinical best practices and dedication to creating a remarkable patient experience that this will occur. Using a value-based pricing strategy is simply your signal to the market that your practice represents these characteristics. Stated differently, without rigorous clinical standards and personalized, responsive service, implementation of a value-based pricing strategy is a waste of time. By offering itemized bundles across three to four price points that list comprehensive services and technology tiered to the attributes customers most value (primarily performance in background noise and personalized service), practices can signal to a wide segment of the market using itemized bundles. This approach represents the next-best alternative to a slew of direct-to-consumer and run-of-the-mill, mediocre service providers. After you have created your own itemized bundles at carefully considered price points, the next step is to communicate the value to each patient during the pre-fitting consultation. As Ron Popeil says, “Now, wait, there’s more.” For audiologists, his mantra signals an opportunity to differentiate their offerings from numerous low-end competitors.

References

Amlani, A.M., Taylor, B., & Weinberg, T. (2011). Increasing hearing aid adoption rates through value-based advertising and price unbundling. Hearing Review, 18(13), 10-17.

Amlani, A. (2009) It’s not immoral to increase hearing aid prices in an inelastic market. Hearing Review, 16(1), 12-16.

Amlani, A., & Taylor, B. (2012) Three known factors that impede hearing aid adoption rates. Hearing Review,19(5), 28-37.

Brady, G. (2010, October). Pricing for profit: how to set realistic profit margins. AudiologyOnline, Article 847. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com/

Bridges. J.F., Lataille, A.T., Buttorff, C., White, S., and Niparko, J.K. (2012). Consumer preferences for hearing aid attributes: A comparison of rating and conjoint analysis methods. Trends in Amplification, 16(1), 40-48.

Coverstone, J. (2012, March). 20Q: Fee for service in an audiology practice. AudiologyOnline, Article 776. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com/

Cowen, T., & Tabarrok, A. (2011). Modern principles of economics (2nd edition). NY: Loose Leaf Publishing.

Kochkin, S. (2007). MarkeTrak VII: Obstacles to adult non-user adoption of hearing aids. Hearing Journal, 60(4), 24-51.

Mohamamed, R. (2010). The 1% Windfall: How successful companies use price to profit and grow. Harper Business: New York, NY.

Ramachandran, V., Stach, B.A., & Becker, E. (2011). Reducing hearing aid cost does not influence device acquisition for milder hearing loss, but eliminating it does. Hearing Journal, 64(5), 10, 12,14,16-18.

Sjoblad, S., & Warren, B. (2011). Myth busters: Can you unbundle and stay in business? Audiology Today, 23(5)36-45.

Tjan, T. (2010, February 26). The pros and cons of bundled pricing [blog post]. Harvard Business Review Blog. Retrieved from: https://blogs.hbr.org/tjan/2010/02/the-pros-and-cons-of-bundled-p.html

Ulwick, A. (2005). What customers want: Using outcome-driven innovation to create breakthrough products and services. McGraw Hill: New York, NY.

Cite this content as:

Taylor, B. (2013, February). Value-based pricing strategies: How to signal quality in your marketplace. AudiologyOnline, Article #11631. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com/