From the Desk of Gus Mueller

Dr. James Jerger is in the house! It’s a pretty exciting time at 20Q when our guest author is someone who, through his research, articles and lectures, has led our profession through the myriad of audiologic diagnostic tests for the past 60 years. He has taught us about threshold measures, masking, the SAL, the SISI, loudness measures, Békésy audiometry (including an unexpected dividend), tone decay, PI-PB functions, tympanometry, acoustic reflexes, speech testing for central pathologies and APD, ABR, OAEs, and a host of other tests and procedures. In other words—just about everything we do as clinicians.

Gus Mueller

That impressive list takes us into the 1990s. So what has he been up to lately, you might ask? After a 35-year “career” at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Dr. Jerger joined the faculty of the University of Texas-Dallas in 1997. At this setting, his research has focused on auditory processing disorders in both children and elderly persons. A specific interest over the past several years has been to examine how auditory event related potentials (AERPs) might expand our understanding of the cognitive factors involved in word recognition. This month, he’s joining us at 20Q to provide a review of this emerging area of audiology.

As I mentioned, it’s been Jim Jerger’s firm hand that has led us through the world of diagnostic audiology for decades. Outside of the clinic, he’s also had a strong presence. More than any other individual, he was responsible for the forming of the American Academy of Audiology, was the first president of this organization, and served as Editor-In-Chief of the Academy’s journal, JAAA, for the first 22 years of its existence. Fittingly, the most prestigious award presented by the Academy each year is the Jerger Career Award For Research In Audiology.

Dr. Jerger’s insights in this 20Q article regarding AERPs will certainly provoke thought and capture your attention. But if you’re sitting down with a legend, and you have 20 questions to use, you just might want to ask a few personal questions, too. Our roving Question Man did just that, and I’m sure that you’ll find Dr. Jerger’s responses to those questions equally compelling.

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

June 2014

To browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles, please visit www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Using Auditory Event-Related Potentials for a Better Understanding of Word Recognition

James Jerger

1. We’re here to talk about some of your recent research, but do you mind if I first ask a few personal questions?

No problem. Ask away.

2. I know you did your audiology training at Northwestern University back in the 1950s. That was an exciting time for audiology. Any favorite memories?

Without a doubt it was the weekly combined audiology/otology clinics at the Northwestern University (NU) medical school in downtown Chicago. It was jointly administered by Ray Carhart and George Shambaugh. The latter was chief of otolaryngology at the NU medical school. Five to six patients selected by Dr. Shambaugh from his private practice came to the medical school on Wednesday morning where they were evaluated by 2-3 audiology students, and examined by an ENT resident and by Dr. Shambaugh himself. When all this had been achieved each patient was “staffed” by Shambaugh and Carhart before an audience consisting of audiology students, residents, nurses and a few secretaries. Shambaugh explained to the patient the situation from a medical perspective, then Carhart covered what non-medical interventions were available. This was back in the early 1950s, when the audiologic armamentarium consisted of the pure tone audiogram, threshold for spondee words, and a PB discrimination score. Similarly the otolaryngologist was limited to X-rays of the internal auditory canal. There was only limited vestibular examination, no sophisticated imaging, and, regrettably, an over reliance on primitive tuning fork tests, both with and without masking of the non-test ear. But to me it was a heady time. We saw two amazing individuals virtually creating a new field before our eyes. I was hooked: I wanted to become a part of it.

3. Was there one certain individual from Northwestern who had a significant impact on your development as a professional?

Yes, Professor Helmer Myklebust. He was simply a natural teacher. His course in aphasia covered everything from the role of language in human affairs to the history of brain disorders in man. He was a scholar who inspired love of learning in his students. My own attempts, over the years, at improving the evaluation of hearing disorders were inspired by his systematic approach to the differential diagnosis of deafness in young children. And of course he pioneered the concept of auditory perceptual disorders as distinct from hearing sensitivity loss, stimulating in me a lifelong interest in the disorder.

4. So after leaving Northwestern . . . is there someone who had a significant effect on your career in audiology?

I would have to say Kenneth O. Johnson. I first met Ken when he came to Northwestern in the late 1950s to consult with Ray Carhart about the ASHA. He had recently taken the job of Executive Secretary of ASHA and was touching base with many of the senior people around the country. We met, talked some, and became good friends. For the next two decades I shuttled a good deal between Chicago and Washington, and later between Houston and Washington, usually for National Institutes of Health (NIH) business and ASHA committee meetings. During that period Ken taught me all I needed to know about the business of professions. He knew how to maneuver in the corridors of power and where all the bodies were buried. I learned the complexities of professions and professional organizations, a helpful background for launching the American Academy of Audiology years later.

5. Thinking back to those early days, is there anyone that you feel has contributed significantly to the profession but has been under-appreciated or unappreciated?

Many names come to mind, but I would have to single out Cordia C. Bunch as the most under-appreciated person in the history of the profession. Bunch was truly the first clinical audiologist. Working in an otologist’s office in St Louis, Bunch used the venerable Western Electric 1-A audiometer to run air-conduction audiograms on thousands of patients during the decades of the 1920s and 1930s. He studied those audiograms, categorized them, theorized about them, then wrote several seminal papers ranging from the damaging effects of noise on hearing to the removal of one brain hemisphere. Shortly before his untimely death in 1942, Bunch accepted a teaching post at Northwestern where he mentored a young speech scientist, Raymond Carhart, on the fundamentals of hearing testing.

6. Most of your career was spent at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, but you’ve now also spent considerable time at the University of Texas at Dallas. Similar experiences?

Not really. The two experiences have been very different. I was in Houston for 35 years, but I have been in Dallas for the past 17 years. At Baylor, I worked in the Department of Otolaryngology/Head & Neck Surgery in the medical school, but at the University of Texas at Dallas (UTD) I have been primarily associated with the Cognition and Neuroscience program in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences. In Houston I was closer to clinical activities. Directing the audiology services in The Methodist Hospital, I met with the audiologists at daily staffings in which we discussed interesting or challenging cases. This provided the patient material for much of the clinical research published during that period. My teaching duties were largely confined to medical students, otolaryngology residents and audiology graduate students. At UTD, however, things took a more academic turn. I have mentored doctoral students in both audiology and neuroscience while pursuing research principally oriented toward auditory event-related potentials and their implications for audiologists.

7. And that’s the topic I’m looking forward to discussing. What has been the general direction of your research at UTD?

Over the years, I have become increasingly concerned that we were not doing a very good job of assessing the successful use of hearing aids and other amplification-based interventions. As hearing aid technology raced ahead with sophisticated digital innovations, we remained mired in the word recognition score. I had long felt that, in our preoccupation with the bottom-up aspects of word recognition, we had neglected the top-down dimension. I was influenced in this direction by the perceptive studies of Arthur Wingfield and his associates at Brandeis University, and by the thought-provoking work of Kathy Pichora-Fuller and Bruce Schneider at the University of Toronto. With the assistance of several excellent graduate students at UTD I set out to explore how electrophysiology, specifically auditory event-related potentials (AERPs), might expand our understanding of the top-down, cognitive factors involved in word recognition and its implications for our clinical evaluations.

8. When you say AERPs, what specifically are you referring to?

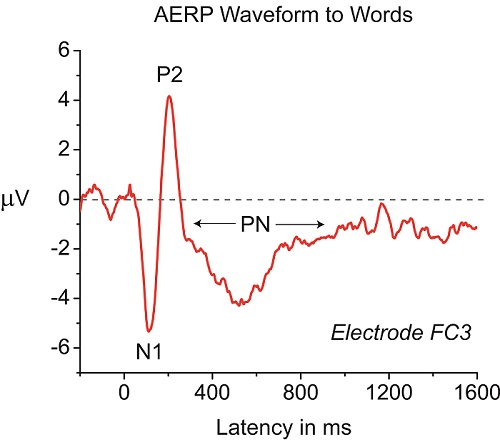

They are evoked, not so much by the auditory events themselves, as for example the auditory brainstem response (ABR), but by listening tasks that require a decision about some events in contrast to other events. For example, suppose that we present the listener with a series of 50 CVC words. Most of the words are chosen at random, but a small percentage, say 15%, are articles of clothing. We instruct the listener to listen to each word and count the number of words that were items of clothing. In AERP parlance the items of clothing are termed “targets” and the other words “non-targets”. Then we separately average the evoked responses to the targets and to the non-targets. The waveform of the non-targets will show three prominent components: the N1, a negative deflection at a latency of about 100 milliseconds (ms); followed by the P2, a positive deflection at about 200 ms; followed by a prolonged negative deflection, the processing negativity or PN, peaking in the 400-500 ms latency range; and returning to baseline 800-1000 ms after word onset. The waveform evoked by the target words will have all three of these components plus a fourth, a slow positive deflection from baseline peaking in the 600-900 ms range, and returning to baseline, termed the “late positive component (LPC).” An example of this is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example of an AERP waveform at electrode FC3 in response to a word. The listening task is repetition of what is heard. Three AERP components, N1, P2, and Processing Negativity (PN), consistently appear.

9. Over the years I’ve seen mention of “40-Hz Potentials,” “Missmatch Negativity,” “P300 Responses,” and the “ASSR.” Aren’t they all AERPs? How are they the same or different from what you are describing here?

That is a very important point. No, they are not all AERPs. They are all AEPs (auditory evoked potentials) but in your list only the P300 is actually an AERP. The E in AEP stands for “evoked”, but the ER in AERP stands for “event-related. The difference is fundamental. Virtually any auditory signal will evoke a brain potential. If you present clicks at a very rapid rate (e.g., 20/sec) you will evoke an ABR; if you present those same clicks at a much slower rate (e.g., 1/sec) you will evoke the N1/P2 complex. These evoked potentials (ABR, MLR, MMN, ASSR, N1/P2) tell us about the brain’s response to the onset of a sound and something of the basic properties of the sound. They can all be measured without any active participation of the listener. Indeed they can all be gathered while the listener is asleep. They are, to be sure, extremely useful in many practical applications, especially estimating degree of sensitivity loss in babies, children and other difficult-to-test individuals. But they contribute little to our understanding of how syllables, words, and sentences, the building blocks of speech communication, are processed. Nor are they immediately helpful in understanding the complex interplay among linguistic processes like phonological and semantic analysis and cognitive processes like memory and attention. For this you must study event-related potentials, the brain activity evoked not by the onset of a series of sounds but by requiring the listener to actively participate in a task requiring a decision.

10. Great. That helps. So back to your research—what exactly do these AERP components tell us about word recognition?

Well, quite a bit, actually. The N1 and P2 components are exceedingly interesting and useful, but our attention rapidly focused on the PN and LPC components. The PN reflects the sum of at least four cognitive processes overlapping in time, but reflecting evoked activity over different regions of the head. They include: attention, phonological processing, working memory, and semantic processing. The LPC component reflects the degree of difficulty in making the decision whether or not a target word has been heard. The easier the decision, the earlier and larger the evoked positivity.

11. Sounds intriguing, but how can this information be used by audiologists?

In a number of ways. First, if you set up the listening tasks appropriately you can get separate estimates of the relative magnitudes of the four cognitive components buried in the PN component. Similarly, structuring the listening task permits an estimate, from the LPC, of the relative difficulty of various tasks. Finally, these two components, collectively, reflect an important dimension of real-life auditory experience, listening effort. It is reflected in both the depth and duration of negativity of the PN component and the onset, height, and duration of the positivity of the LPC.

12. Listening effort. Is that something I should be concerned with?

Most definitely. It represents a heretofore largely ignored dimension of real-life auditory communication. Let me give you an example. If you have ever carried out a study comparing two different amplification systems, you may very well have found that while the group as a whole prefers one system over the other, conventional word recognition tests, either in quiet or in competing noise, fail to show a significant group difference. Could such a finding reflect less listening effort for the preferred system in spite of the negative statistical outcome on standardized tests?

Or, consider people that you have fitted with hearing aids. We know that laboratory research using word recognition testing shows little or no benefit for today’s digital noise reduction. Yet, you’ve probably had patients who have reported doing better when fitted with this technology. Could it be that they experienced less listening effort, which allowed them to use other cognitive skills to more effectively communicate?

13. Good point. Have there been studies which have compared AERP findings to the patient’s subjective report of listening effort?

First, there is face validity in the idea that “listening effort “ is proportional to the extent to which the listener must marshal factors of phonological analysis, semantic analysis, attention and working memory in word recognition. A more direct approach would be to have listeners rate their degree of listening effort over a variety of tasks of varying difficulty, then assess the degree of correlation of those ratings with AERP data. And that could certainly be done. Yet designing studies in this area is not without its own problems. We have elected a more direct approach, manipulating the degree of difficulty substantially and comparing concomitant AERP results. For example, we presented the same list of words to listeners under two conditions: in one condition they were instructed to simply repeat the words back; in the other they were instructed to count the number of words that were names of animals. As expected the PN component was more negative in the second condition. And the PN difference was greater in hearing-impaired than in normally hearing listeners.

14. I would think that there would be an aging effect. Is this true?

Yes, there are aging effects on AERPs but they are more complicated than you might at first think. As age increases beyond 60 years, the amplitude of the N1 peak declines slightly and the peak latency increases slightly but the effects are not remarkable. However, hemispheric asymmetry of the N1 peak amplitude favors the left hemisphere in children but declines in young and middle-aged adults, and disappears in elderly persons. It has been reported, moreover, that the P2 latency increases more than the N1 in elderly persons. In contrast, both the PN and LPC components change substantially with age. Amplitude declines and latency increases systematically.

15. Earlier you mentioned that the AERP tells us about attention. Is this also something I should be thinking about?

If you are interested in auditory processing disorders (APD) you had better be interested in attention. There is a growing body of converging evidence that attention plays a major role in this disorder, especially in common assessment tools, such as tests of dichotic listening. It is the case that the PN component of the AERP permits us to evaluate the comparative contributions of attention and other cognitive processes on simple to complex listening tasks. It is a matter of structuring the listening task appropriately.

16. Can you give me an example of such a listening task?

Certainly. Consider the case of a child suspected of APD. Suppose that we present a series of CVC words in which 80% are chosen at random and the remaining 20% are from the category "articles of clothing". We present the words under two conditions: 1.) the child is instructed to ignore all of the words while watching an engaging cartoon on a video monitor; 2.) now the child is instructed to listen to each word and count the number of words that are articles of clothing. In the first condition, the negative PN component of the AERP to non-target words should reflect only minimal semantic processing, and the LPC component to target words should be absent. In the second condition however, the PN component of the AERP to the non-target words should reflect the sum of semantic processing and attentional processing, and the LPC to target words should be robust. Comparison of PN and LPC components under the two conditions will yield an estimate of the relative contributions of semantic processing and attention to non-target words, and the ease or difficulty of the decision-making process for target words.

17. So if a child did poorly on a clinical dichotic speech test, would you also expect to see an abnormal AERP, or isn’t it that simple?

No, it is seldom that simple. For example, if the behavioral test result is due to a genuinely abnormal left-ear deficit in the dichotic processing mode, then that fact should be reflected in a similar asymmetry in PN and LPC amplitudes. But if the poor performance is the result of inadequate control of attention, either on the part of the tester or the child, then that factor will probably be reflected very differently in the inter-aural comparisons. This is precisely why AERPs should be a part of such testing.

18. A practical question—do the manufacturers of ABR systems incorporate equipment features that allow for the measure of these speech-evoked cortical responses?

Since commercially available ABR systems are designed for efficiency in a totally different application, they do not lend themselves easily to AERP applications. The problem is getting the system to present speech stimuli at a comparatively slow rate and synchronizing the onset of the speech stimulus with the onset of an EEG epoch extending over 2-3 seconds. The system that we use, Neuroscan, manufactured by Compumedics, does all of this very nicely because that is what it was designed to do. Other similar systems are also available commercially. In the long run I suspect that one of these commercial systems would be more cost effective than attempting to modify an existing ABR system.

19. Thanks. My twenty questions are almost up, so I’d like to end by asking a couple things about our profession. What advice would you offer to audiology students who may wonder if becoming an audiologist is worth the effort and accumulated debt?

At a time in our economy when the overall jobless rate hovers around 7%, there are not enough trained audiologists to fill all the open positions. Virtually every forecast suggests that the future is very bright indeed for health-care workers in general, and audiologists in particular. As I weigh the cost of advanced education against the long-term payoff, not only financially but in terms of career satisfaction, education always wins.

20. Do you see any serious threats to the future of audiology?

There has been a serious threat to the profession from the day that the ASHA decided it was not unethical to dispense hearing aids. Ken Johnson, longtime executive secretary of ASHA, warned us about it more than 40 years ago. The danger is that we will just replace old-fashioned hearing aid dealers with newly minted hearing aid dealers, called AuDs. And that danger increases with every addition to the current roster of AuD programs. What can we do to prevent it?

- Find some way to limit the number of AuD programs to a quantity that the resources of the profession can sustain at an acceptable level of quality education.

- Strengthen the scientific base of the profession by placing a greater emphasis, in all doctoral programs, on understanding the important role of research and research training in this and any other profession.

- Take positive steps to preserve and increase the number of high-quality PhD training programs.

- Recruit students from psychology and engineering who bring stronger science backgrounds to the profession.

- Take positive steps to breach the wall between clinicians and researchers that exists in too many university programs.

Citation

Jerger, J. (2014, June). 20Q: Using auditoryevent-related potentials for a better understanding of word recognition. AudiologyOnline, Article 12731. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com