Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live seminar. Download supplemental course materials.

Dr. Lisa Christensen: Today’s course is Understanding Atresia, Microtia, and the Baha System. The topics we will cover today are atresia versus microtia, softbands, the bone-anchored hearing system (Baha) implant, and the expectations and considerations from a family’s perspective.

Terminology

Microtia

First, I would like to review the difference between microtia and atresia. Even as audiologists, we sometimes use the terms loosely, so it's important to define the terminology. Microtia refers to the spectrum of deformities of the external ear. It is typically categorized into four different grades. Grade 1 is a slightly smaller ear with the majority of the structure still present. Grade 2 has a little more deficiency of the ear structure. Grade 3, is absence of an external ear, with a peanut-like vestige, for lack of a better term. Grade 4, also known as anotia, is the total absence of the external ear. Images of these grades can be found at www.microtiaearsurgery.com

Regarding microtia, there are several different modes of treatment. With microtia, we are mainly dealing with cosmetics of the outer ear. Prosthetics work best with anotia, but we are going to look at some cases later where that can be achieved by other means. There are traditional prosthetics that are glued on. If you Google prosthetics for faces, you will find nose prosthetics, ear prosthetics, and others. There is also VistaFix that instead of being glued on, attaches similarly to the Baha implant.

There is also surgical reconstruction for microtia. On average, this consists of three to four surgeries, and there are two widely accepted techniques. The first is a rib graft technique that was started back in the 1920s. It uses your body’s own biological tissue, specifically rib cartilage and skin. There are two different rib graft techniques: the Brent technique and the Nagata technique. The Brent technique typically uses three stages (surgeries), and sometimes four. The Nagata technique usually uses two stages, but this will vary depending on each individual.

MEDPOR reconstruction uses synthetic material for reconstruction. They begin reconstruction in children at younger ages. The usual age requirement is between 5 and 8 years of age, primarily because of the growth of the child. This is the same age requirement for VistaFix. It is usually the same as the Baha criteria: the guideline from the FDA is about 5 years old. Many of these criteria depend on the growth of the child, which is why you see similar age requirements for the various procedures.

Atresia

Atresia is the absence or closure of the external auditory canal. You will sometimes hear it called aural atresia, meaning ear atresia. Congenital aural atresia occurs in approximately 1 in 10,000 to 20,000 live births. Unilateral atresia is more common. Males are more affected than females, and interestingly, the right ear is more commonly affected in unilateral cases. There are also several syndromes associated with atresia. The most common syndrome that comes to mind is Treacher-Collins. There are others such as Goldenhar, Crouzon, Mobius, Klippel-Feil, Fanconi, DiGeorge, VATER, CHARGE and Pierre Robin. All of these syndromes are associated with the risk of aural atresia.

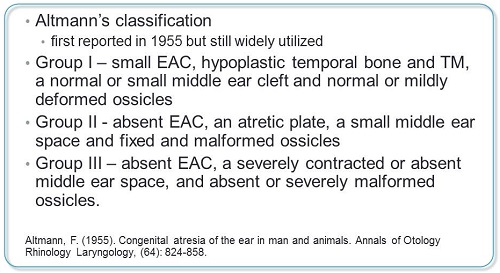

Atresia also has four different classifications. The first classification, Altmann’s classification, dates back to 1955, and it is still widely used. Many surgeons will tell you the atresia is Group I, II, or III (Figure 1). If you look through the classifications, you will see that Group I has a small external auditory canal. In Groups II and III, there are absent external auditory canals. Each group has a varying degree of closure or severity, and each one goes farther back into the middle ear.

Figure 1. Atresia classification.

The other common classification for atresia that has been used since 1992 is by a score system from 1 to 10. This is usually based on the findings of high-resolution CT scans. These high-resolution CT scans have changed the way that atresia is modified and repaired, as they can look into the ear, and decide, based upon those findings, what they think their chances are of a good repair and good hearing at the end. The interesting thing about this classification system is that it establishes a score of 1 to 10 based on different factors (Jahrsdoerfer, 1992). For example, the presence of a stapes will receive two points. If you have a stapes, you are probably going to have a better atresia repair.

A score of 8 out of 10 is an 80% chance for restoration of hearing to normal or near-normal levels. They define that as speech recognition thresholds between 15 and 25 dB. Cases with a score of 5 or less are generally not considered for surgical intervention. Those patients end up with other prosthetic devices, hearing aids, or other things that they need as the atresia cannot be repaired.

Atresia Repair

When you look at atresia repair, there are a few things to consider. First is candidacy. There are usually facial nerve complications. We have to look at hearing outcomes. Children with Treacher-Collins syndrome are notorious for having a facial nerve that is not in line as it should be. When going in to repair the atresia, you can also have facial paralysis as a result and complication of the surgery. Therefore, using the high-resolution CT scans allow the surgeons to look for the facial nerve course to be sure that they are not in danger of hitting it during surgery and causing long-term paralysis. There is also the patency of the repair. How long is it going to stay there?

The age of the patient is probably one of the biggest factors. Age is what families worry about and when it is going to happen. High-resolution CT scan has impacted the atresia repair because you can determine the condition of the ossicles, the presence or absence of round and oval windows, the course of the facial nerve, and any kind of air and ventilation of the middle ear and the mastoid. Those things are important when they go in to see if this is going to be an atresia repair that will restore the majority of hearing.

As with any surgical procedure, there is also a risk of complications during atresia repair. Some of those include facial nerve injury, which can be temporary, but in most cases it is permanent if it is completely resected in surgery. There is a tympanic membrane lateralization where the eardrum does not stay like it should; it falls down. One of the biggest things that I have seen is the re-stenosis of the canal. I will tell you that it is more of a global problem when you look at atresia repair. I have a daughter who is nine years who had choanal atresia, which is closure of a nasal passage. She had multiple surgeries in the beginning to keep that passage open. It is not something that is common to the ears. In her case, it was common to a nose, and as her surgeon described to us, re-stenosis is another concern as she ages and grows, just like it is with children with the atresia repair on their ears.

There is also a degree and risk of ossicular refixation. When the ossicles have been repaired to move and perform as they were intended, over time, sometimes those bones stiffen up again and the hearing loss returns. In extreme cases, there is a chance of sensorineural hearing loss developing when there is an issue surgically. There is also the chance of canal cholesteatomas. When there is so much skin and debris that sticks in the canal, it can cause a cholesteatoma, which has to be surgically removed.

As audiologists, we are generally concerned about the percentage of cases that have successful outcomes. If you have done some research on this, you know that that is going to vary greatly. A study from Tollefson (2006) looked at 14 specialized centers; they defined “specialized” as seeing a large population of children and adults with atresia. This study included 595 total patients, and 48% of those patients initially after surgery had less than or equal to 30 dB of gain back in air conduction. I think 30 dB is a lot of gain to give back to a child when we have lost an ear, but what about a child with a 60 dB loss? This still leaves them with a mild hearing loss with the need for FM systems or soundfield systems and modifications. That is an important consideration when surgically fixing an ear, especially when we work with children.

There was another study by Lambert in 1998 that I like better. The majority of the research, as is pointed out in this article, cites hearing results that are attained soon after surgical repair. The biggest thing with this report is that stability is the key. As audiologists, stability is what we consider important, because we want to know what is not going to be okay six weeks after surgery and what is going to be okay, especially for a small child who is still learning and in school. We want to make sure that the hearing is going to stay good and that the child will not be back in surgery every six months reopening a canal. This is more of a focus on the long-term.

Lambert (1998) found that 60% of the cases had hearing levels of 25 dB or better, and 70% of the cases he received were 30 dB or better, but that was early post-operative. The important thing on this study is that those results diminished from 60% to 46% and from 70% to 50% with longer follow-up. A decent percentage of the people compared in this study started to have hearing loss again over time. Nearly one-third of those cases required revision surgery for re-stenosis of the external auditory canal or lateralized tympanic membranes.

After revision surgeries, he found that hearing levels of 25 dB or less were achieved in 50% of the cases, and the levels of 30 dB or less were achieved in nearly two-thirds of cases. An interesting part of this study was that of patients with an exceptional result in the primary surgery (hearing thresholds of 10 to 20 dB), 83% maintained that outcome over a longer period of time. The ones that did well in the beginning continued to do well with the fewest problems, but the ones who were marginal in the beginning, who were barely getting the 30 dB of gain, were the ones who seemed to have progressive problems.

Baha System

We have looked at microtia, microtia repair, atresia and atresia repair. Now let’s talk about out third option, which is using the Baha system. For those of you who work with Baha, you know that this device and osseointegrated devices have been used to treat conductive and mixed hearing loss since 1977. Bone-anchored hearing systems work by direct bone conduction. Sound is conducted through the bones of the skull, bypassing the outer and middle ear where the microtia and atresia would occur, directly stimulating the cochlea. It has three parts: the internal titanium implant, the external attachment or abutment, and a detachable sound processor. Figure 2 is an example of the Baha implant where you can see all three pieces. The part that looks like a screw is the internal implant. The abutment sticks through the skin, and the sound processor is attached to the abutment behind the ear.

Figure 2. Baha osseointegrated system, with internal implant, abutment, and sound processor (on outside of head).

The Baha is typically worn as either a softband (Figure 3) or an implantable device. The softbands have no age restrictions. We can put a softband on an infant just as soon as we know there is a hearing loss. They are typically used for bilateral conductive losses. They can also be used with a conductive hearing loss in the case of unilateral atresia. You can get a unilateral or a bilateral softband. The benefit is that we can get these children hearing well with a softband early on.

Figure 3. The Baha softband, shown in a bilateral option.

The FDA has some recommendations, as they do with many things in audiology and health care. They recommend that this be implanted at five years of age or older. We talked before about how atresia repairs and microtia repairs are typically done around five to eight years of age, depending on who does the surgery, what different type of surgical repair is needed, and which one is done. That pulls into the different children and what the age ranges could be. This is the same with the softband. It can be a bilateral or unilateral implant.

Softband Results

We have looked at the results with atresia repair and microtia repair, but now we want to look at what happens with the softband. I would like to talk about a study in which I participated several years ago (Nicholson, Christensen, Dornhoffer, Martin, & Smith-Olinde, 2011). We looked at the charts of Baha patients in a retrospective study of infants and children from about 2002 to 2006. We found 20 infants and children that met inclusion criteria. The average age was about five years. There was one 16-year-old, and people always ask me about that. This was a child that had many surgeries and chose to not have the Baha implanted out of not wanting another surgery. Typically we have a bilateral, symmetrical conductive hearing loss. There were many syndromic statuses that we talked about earlier, including Treacher-Collins, Pierre Robin, and CHARGE. However, we looked for symmetric conductive loss for this study. These children were fit unilaterally on a softband.

The children’s threshold averages were around 60 dB at 500 and 1000 Hz to 55 dB at 2000 and 40000 Hz. We tested 500 to 4000 Hz, assuming that we would assess the audibility of most of the speech spectrum for patients. The average functional gain was about 40 dB in the low frequencies to 35 dB in the higher frequencies. In aided soundfield, we were seeing about 20 dB thresholds for all frequencies. We feel that was very good data to have.

There was good functional gain for these children, which was encouraging, especially when we evaluate young children who need to be seen early for speech and language. Another quick note on the softband is that when we do fit the softband as early as possible, we are following the early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) guidelines that pediatric audiologists strive to get with rescreens by one month, the diagnosis by three months, and the intervention by six months. We all strive for those, but we have to look through and decide how best to achieve those for some of these children.

In another study, we wanted to make a comparison between traditional bone conduction hearing aids and the softband, as well as obtain some implanted data (Christensen, Smith-Olinde, Kimberlain, Richter, & Dornhoffer, 2010). This was done with 10 children. It was a little difficult to find 10 children who have worn traditional bone conduction aids, especially here in Arkansas. We have been using softbands for a long time. It is hard to dig back and find those traditional bone conduction aids. However, we found 10 subjects for this study in 2010. Their ages were 6 months to 18 years of age through the entire study. As with the other softband study, we wanted to get subjects with congenital bilateral conductive losses. We wanted them to be initially fit with a traditional bone conduction aid, then we wanted them fit with a softband. This was a unilateral study, initiated before we started implanting bilaterally.

We looked at unaided and aided soundfield thresholds for the same speech frequencies of 500 to 4000 Hz. The results of the study show the audiometric bone conduction transducer, which is unmasked bone conduction, provided the highest amount of functional gain. The implanted Baha system provided the second highest amount of functional gain. The softband provided the third amount of highest functional gain, and the traditional bone conduction provided the least amount.

The unaided thresholds were approximately between 55 and 60 dB, conductive hearing losses. The implanted Baha was very similar to unmasked bone conduction. The only difference between the implanted Baha and the softband is the skin and the hair that is between the transducer and the implant. We were surprised that the traditional bone conduction hearing aid did not get better results. There have been many questions as to why we think that was not portrayed as well as we thought it would be. I think most of that has to do with the fit of the softband; it fits a little bit better than the previous metal bone conduction headband. Those metal headbands, due to their poor fit on smaller heads, probably did not get worn as much as we would have liked for them to have been.

There are a few statistical things that we found. The implanted Baha had as much gain as the bone conduction transducer. Statistically they were the same. I think that is important for us to recognize. The implanted Baha had more gain at 500 Hz than the Baha attached to a softband. It makes sense that the lower-frequency region transmission was more hindered by the skin and hair for the traditional bone conduction aid.

Treatment Decisions

The ultimate decision maker regarding the treatment decision is the family. There is no rule anywhere that says someone with microtia has to undergo reconstructive surgery. There is no law that says that they cannot live their life with Grade III deformity and move through. We have to always consider that option as we work with families. Audiologists must know all the facts and be current on evidence-based research. As audiologists, we need to know about atresia and atresia repair, including outcomes. We need to know what happens with a microtia repair, and how many surgeries a family might expect. We need to know about Baha softbands. Do they provide the adequate amount of gain that they should? We need to know about the implantable device. Does that provide as much gain as we think these children should have based on what we know about language and listening from an early age? Each family is going to need their audiologist to know so many of these things. It is most often the audiologist, not the surgeon, who gets those calls from parents needing information and facts.

In most cases, one size does not fit all. We cannot take a cookie-cutter approach with all children. When you work with children, it is imperative that families understand the urgency of fitting this amplification. Think back to those EHDI 1-3-6 guidelines.

Unilateral Losses

But what if it is just a unilateral hearing loss? This is a question I get asked all the time, especially from physicians. Many unilateral microtias get overlooked. There is a great study from 2013 that compared a unilateral sensorineural hearing loss to a unilateral atresia for academic performance (Kesser, Krook, & Gray, 2013). This is a great study because we have focused ourselves on all of the problems children with unilateral profound sensorineural hearing have in school for some time now. This study looked back at 40 patients who had unilateral atresia. Unlike their counterparts with sensorineural loss on which we have focused so much, none of those children repeated a grade. However, 65% of those children still needed some sort of resources at school. Almost 13% of them used a hearing aid, and 32.5% used an FM system at school. Forty-seven percent of those children had an individualized education plan (IEP) at school. Moreover, 45% of the children in this study where in speech therapy for just that unilateral atresia.

The conclusions from this study (Kesser, et al., 2013) were that those unilateral conductive atresias have an academic limitation. That hearing loss does affect academic performance, especially in the children they study. However, it is not as a profound impact as the unilateral sensorineural loss. As pediatric audiologists, I would venture to say that they type of hearing loss does not matter to most us, especially to me as a parent. Having that 65% needing help is enough for me to step in and know we have to do this for these children.

Family Discussions

We are going to spend the last portion of our talk today discussing some family cases, because we need to know a different perspective. As audiologists, we tend to focus our concentration on hearing. All we want to do is get devices on these children. We want to start moving full steam ahead. We know the EHDI guidelines. We know what will happen to speech and language development and academics if we do not act quickly and smartly. We get intensely focused in on that.

Our surgeons, otolaryngologists and facial plastics people get concentrated on the surgical solutions. They dive in and are ready. Families are waiting and know they have to wait for a certain period of time, but they are ready for the surgery. I know many cases where the audiologist sees the family, the surgeon sees the family, and the surgeon does not see them again until they are between five and eight years old. The audiologist has to be there to be the gatekeeper.

I thought it would be interesting to sit down and have discussions with three different families. Their children have three different types of hearing loss. The first family that we will talk about has a child with unilateral atresia and microtia. He is currently four years old. The second family has a child with bilateral atresia and is six years old. The third family has an 18-year-old with Goldenhar syndrome and bilateral atresia and microtia.

I had eight main topics that I asked them to discuss with me. I wanted to know about their diagnosis: How did it go? When did they receive it? Did they know before birth? For the four-year-old and six-year-old, was this picked up on an ultrasound prior to birth?

I wanted to know about their treatment options. Where are they currently? What happened? Did they follow all the treatment options that were given to them? Did they find options on their own? Were they happy with what they had chosen?

Then I wanted to know about professionals. As an audiologist, I feel I get most of the calls, where I am sure that surgeons with whom I have worked in the past do not get as many. I wanted to know what professionals they felt guided them through the journey, so we would have an idea of where we were going as professionals and what we needed to do to help them.

Almost a dreaded question, I asked what they searched for on the Internet. What did they find out? Did they like what they found when they Googled things? Did it help them? Did it hurt their opinion?

We talked about initial treatments, what they did first. We talked about what they thought the future held for their children, for their lives, and also early amplifications issues that they had. Then I asked them what their advice was for new parents. I have some very interesting things to share.

Family 1

Let’s start with the first family. This little boy has left-ear microtia and atresia. Thinking back to what we just learned, the right ear is more commonly affected. He has a normal right ear. They went to the ear, nose, throat physician (ENT) first, not audiology. Even though he failed a newborn hearing screening and they could see the microtia, they were still sent to ENT first. They were not even thinking about the hearing part their first trip in.

At this point, the ENT does not have a lot to do. In many cases, the physician will tell them to wait until the child is five years and come back then to look at surgical options. Luckily, they got in with a great otologist who did not let them believe that unilateral hearing loss was no big deal. He discussed the microtia and graded it on the first visit. He talked about surgical procedures and Baha, and he also followed that up with a trip to the audiologist in the same clinic to discuss their portion of it. I do have to say that this is a dream family. This is the kind of family you want to come through your door every day. Their main focus was the whole picture of their child, not just the individual conditions. They had done research. They knew the methods, the upcoming choices to be made, what professionals they needed, and they knew they could not do nothing.

The mom said, “The local ENT was very knowledgeable about atresia, but our son has microtia as well.” She knew that it was a dual condition and that they were interconnected. She knew that they could choose to reconstruct using a rib graft. She knew they could choose the MEDPOR method. They knew where the canaloplasty would fall in. They knew another option would be to do nothing. They were aware of their treatment options in the beginning.

When I asked her about professionals, their main professional was their audiologist. That person was the one there to educate them on amplification. They helped them weigh the benefits and start the process of obtaining a hearing aid. They discussed what age would be appropriate for that hearing aid. I have a little bit of a bias when fitting softbands with these younger children, especially unilateral children. If you have a child who is under six months who is not sitting up by himself and you try to put a softband with the sound processor behind the affected ear, when they are in a car seat or lying on their back during the day, you are going to have a lot of feedback. The processor will pop off. It is not ideal. In a bilateral case, you can change the placement of the processor a little and get it on them a little bit earlier. For the unilateral children, I have a personal preference for those children to be sitting up on their own before we place the processor behind the affected ear.

I asked the mother about what she researched on the Internet. Sometimes we it is challenging when families come in and they have diagnosed their child from the Internet. However, in this case, it turned out very well. She found an online support group that was specific for microtia and atresia. She raved about this group because they are in a town that is not big. With 1 in 10,000 to 20,000 children with atresia, she was not likely to find many other parents locally with whom she could talk. She supported the use of an online group for herself and for other people. She researched top surgeons. They found a conference specific to microtia and atresia, and they went when the child was just nine months old. She says, “We were not naïve that the surgeons were soliciting potential business for themselves, but it was also educational and informative for us as parents.” Even at nine months old, they were ready to go in and see what was offered in the world so they would have a plan for their child.

I asked again about their initial treatments. The only option for him at that point was a softband because of the microtia. I believe he was a Grade III microtia, and there was no opening that we could work with to try a conventional hearing aid. They were provided with a loaner processor while their own processor was ordered. It was an interesting battle with the insurance company for a few months. The audiologist’s advice was to wait until the child was holding his head up. I did fit this child around the age of seven months. We were only one month behind the EHDI guideline. It was a better experience for mother, father, and child, to have that time for him to sit up and to not have a negative experience on the front end with that device.

I asked her about the future. At the time of the interview, her son was four years old, and they have made no definite decisions. She says, “He is just four now, so no final decisions.” They are even more hesitant at this point as he gets closer to the age where surgical intervention is an option. In a phone conversation, she has said that they are more anxious now than they have been before, because the time they have been waiting for is now approaching and decisions need to be made. They are looking at future technology. She mentions, “In the four-and-a-half years since our son was born, the medical community has made great strides with “growing” ears in labs, and we do not want to rush into anything at this time.” They have seen a lot of technology changes just in the four years that they have had their son.

The next step in their process right now is the CT scan. They will determine at that point if a canaloplasty is even an option and if atresia repair is an option. Some of the surgeons here hold off until about five years of age. By this time, the children will have fully developed and will have a better idea of what is inside. So, this family is in a holding pattern. I think that is often the most difficult aspect of the process with families. This is why I like families to be routinely seen by an audiologist. There is probably not a whole lot we need to do every six months with these children, but they do need support, especially when they do not have local groups that they can talk face-to-face with. The local support of an audiologist, who can sit down and go over some of the information, is very helpful. It supports families on a frequent basis so they do not feel lonely or discouraged in that process.

The child wears the softband daily. They are considering foregoing the canaloplasty to implant the Baha at this point. She says, “There are no easy decisions for a family.” When I asked her about early amplification, she said that they were really happy they chose to aid their son. He is used to wearing it now. There are not nearly as many struggles now, yet there are still days when he does not want to put it on. She acknowledges that it is better because they did start early and it is now second nature to him.

The best thing about her interview was the advice that she gave. First and foremost, she says if she had to give advice to any family, she would congratulate them on their baby and tell them that everything will be okay. I think that is very important for so many other families to hear. She says, “There is a grieving process with anything not being as one expects when a child is born.” I like how she says that. She does not say “broken” or “wrong,” just “not as expected.” It was not what they expected when he was born.

She loves the support groups. She feels those have been invaluable to her and her family. She meets locally with their Hands & Voices local chapter. The online groups which are specific to atresia and microtia, but she says that there are no other families involved in Hands & Voices that have children with microtia and atresia. She says, “Get used to questions from strangers. One of the strangest questions she got asked in a store in reference to the Baha on the softband was, “Is that a tracking device?” She has learned to have thicker skin and to educate others on her son’s condition.

Teaching children to be their own advocate is something else with which she has done a great job. Her child knows exactly what he wears and why. He will also give his own explanation when she explains the Baha to a friend. He says, “My ear does not have an opening on that side.” I honestly think that even at four years old, that will bring him closer to keeping this device on and knowing what he needs to do.

Family 2

The second family has a child with bilateral atresia and no microtia. Currently, he is six years old. This child failed a newborn hearing screening in the hospital, but no one looked in his ears. They knew he failed, but they did not know what to do. At about two weeks old, parents took him to see a physician. The physician looked in his ears and could not see anything. I suspect it was their normal pediatrician and he looked for eardrums to see if there was fluid or debris that would keep him from passing the newborn hearing screening before he referred them to an audiologist. He was not able to visualize a tympanic membrane. By about two months, they got him into the ENT. This was another direct line to the ENT.

They were told that treatment option for his age was a softband as soon as possible. He had very stenotic canals. I think we swayed their opinion to that a little bit by holding the two devices out saying, “This is a traditional behind the ear hearing aid, this is the ear mold, and this is the Baha and softband.” We explained to them how stenotic his ear canals were, even though his outside pinnae looked perfect. We explained the differences in how we were going to keep each device on, and ultimately it was their choice.

I think they felt the Baha was the best option for them at that point because of the difficulty we would potentially have in trying to keep ear molds on. They were told to be fit as soon as possible, and because this was a bilateral conductive case, we treated this softband fitting just like a typical pediatric fitting. We fit him at four months, and we verified this with behavioral observation audiometry. He was not big enough to sit up for visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA), and there is not a way to check real-ear measurements or other verification typically used with an infant under 6 months of age for the Baha softband. We had to use some of those older behavioral techniques to get some information on this child to make sure that this hearing aid was verified before he left wearing it.

They were told early in the process that they would not know if he was a surgical candidate until he was age five. That is not uncommon. Many of these families are left in a holding pattern until a specific point in time. The way it was described to this mother by, most likely, the surgeon was that if he was a surgical candidate, they would find out at age five through a CT scan. If he was a candidate, they would be able to surgically correct his ears then, or as a fall back, he could get a Baha implant. Unlike the mom in the first case who had done more research after she met with the ENT and knew there were more options, this family was not given many options.

There were some differences in how these families were counseled by the ENT at first meeting. When she was asked about which professional she felt guided them, the only thing she had to say was that the ENT and the audiologist worked together to guide them through the process. It is important at this point to remind everyone that it is a team effort. Sometimes it requires more of a team effort than some of us can do, depending on our location or where we are working, but there has to be collaboration between the audiologist and the surgeon. You have to work together and know the family, know what is best for them, and you have to be able to give them all the options as they need them.

When I asked her about the Internet, she said they did lots of searching online in the beginning. I am always hesitant when families get online too much. I had a patient who came in at a couple of weeks old and she had bilateral atresia, but no microtia, with normal looking pinnae for the most part and very mild Treacher-Collins characteristics. When the family came in and I looked at the baby, I knew quickly that it looked like Treacher-Collins, but they did not know that. I grabbed the surgeon to make him say that instead of me. I immediately told them that I knew they were going to go home and look on the Internet, but they needed to look with caution. Their baby had a very mild case. You do not know if the Internet is going to discourage families, or if it is going to move them forward as it did with the first family.

As far as treatment, he had atresia repair. They are pleased with their choice to do that. He is near normal in both ears. He has a soundfield system in his classroom, because he does have a little bit of a high-frequency loss. An important part here is they met with several doctors before they made a decision on a surgeon. They went out of state to have their surgery done. They did not just want to use what was convenient; they wanted to find out what was available. I will say that families really want to see results. They want to see audiological results, especially with microtia repairs; they want to see pictures of before and after. Many families ask to see those from the surgeon they are going to use, not from the ones they find online.

Her advice for other families was also great. She said, “Aid as soon as possible.” Their son has only had some minor articulation issues with very normal language. She advises people to stay on top of the early care with ENT and audiology. She said, “The Baha sound processor will soon be just a part of getting dressed.” When your child gets up, if you have made it a routine, they will get up, put it on, and head out. It was obvious that they were seeing an auditory-verbal therapist because she says, “We wear it all waking hours.” She also says that he asks for it every morning.

Family 3

The third family has an 18-year-old daughter with Goldenhar syndrome. She was diagnosed at birth. 18 years ago, the mother did not have the technology of ultrasounds that we can use now. When she was born, she was transported to another hospital with a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) because of facial paralysis and deformed ears. They said they did not know anything about that condition until she was born. This family not given a treatment option for hear hearing. The doctors said when she was older, around age eight, that she would need atresia and microtia repair. They were told there would be two separate surgeons. One would do the facial plastics part on the microtia repair and the otologist would repair the internal part so she could hear.

She saw the audiologist soon after birth. They attempted to fit a behind-the-ear (BTE) hearing aid on one ear that could accommodate an ear mold on. By a year old, they changed to a bone conduction aid because of the difficulty of wearing the BTE. As for professionals, this family was going through the motions and having the surgical repairs and the things that had been started with them early on by the surgeons. It was their audiologist who mentioned the Baha. They did the CT scan earlier when she was old enough to start surgical repair, but they found that it was not promising for atresia repair. The Baha on a softband or the bone conduction aid were her only options.

In talking with them about the microtia repair, the only thing the mom says is that it was a mess. She was a senior in high school. She never wore her hair up because of the way it looked. They were unhappy with it. It took a few more surgeries than what was indicated in the beginning. She ended up having another surgery to remove the new microtia-repaired ears. So basically she had anotia, or no ear, by choice. They put a VistaFix on one side and a Baha implanted on that same side. Because of some jaw issues and facial asymmetry, they could not do any surgical modifications on the other side, as it was too close to her jaw. On that side, they have no aid, but a prosthetic ear that is glued on.

Her advice to families is that they were unhappy with the microtia repair. She has had a lot of pain, a lot of surgery, and a lot of things that she did not enjoy and does not like to talk about now, all to end up with an option that they were not given right in the beginning. You, as an audiologist, know that with her being 18 now, that was not a choice when she was 5. They are happy with what they have now and they feel the Baha has been a great choice. The only issues they have had are a couple of keloids and some skin issues right around the abutment.

Conclusion

You have to know all the options for families. Many times, you may be the only professional that is there on a consistent basis to guide them through the process. Know what surgical techniques are available near you. You may not have an otologist or a facial plastics person to do these things in your area. You may have to find them elsewhere. The family may be Internet savvy and search these options out themselves, but it always helps for us to give them a good way to get going. You need to know your audiological outcomes for each option. Our job as audiologists is to make sure that our patients can hear as best as possible. Do not wait, especially on those unilateral losses. Do not wait for surgical decisions to start your auditory intervention. Start early with the unilateral losses and get them fit as necessary.

References

Altmann, F. (1955). Congenital atresia of the ear in man and animals. Annals of Otology Rhinology Laryngology, 64, 824-858.

Christensen, L., Smith-Olinde, L., Kimberlain, J., Richter, G., & Dornhoffer, J. (2010). Comparison of traditional bone-conduction hearing aids with the Baha system. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 21(4), 267-273. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.21.4.5.

Jahrsdoerfer, R. A., Yeakley, J. W., Aguilar, E. A., Cole, R. R., & Gray, L. C. (1992). Grading system for the selection of patients with congenital aural atresia. American Journal of Otology, 13(1), 6-12.

Nicholson, N. Christensen, L, Dornhoffer, J. Martin, P, Smith-Olinde, L. (2011).Verification of speech spectrum audibility for pediatric Baha Softband users with craionfacial anomalies. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 48(1), 56-65. doi: 10.1597/08-178.

Lambert, P. R. (1998). Congenital aural atresia: stability of surgical results. Laryngoscope, 108, 1801-1805.

Kesser, B. W., Krook, K., & Gray, L. C. (2013). Impact of unilateral conductive hearing loss due to aural atresia on academic performance in children. Laryngoscope, 123(9), 2270-2275. doi: 10.1002/lary.24055.

Tollefson, T. (2006). Advances in the treatment of microtia. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, 14, 412-422.

Cite this content as:

Christensen, L. (2014, July). Understanding atresia, microtia, and the Baha System. AudiologyOnline, Article 12793. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com