This is an edited transcript of an Oticon Medical webinar on AudiologyOnline.

Learning Objectives

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the impact of unilateral hearing loss on the pediatric patient.

- Describe the delays that are often associated with unilateral hearing loss.

- Describe the different treatment options for the pediatric patient with unilateral hearing loss.

- Explain how the technology of the Ponto system can help a child with unilateral hearing loss.

Introduction and Overview

Melissa Tumblin: Welcome and thank you for attending this presentation on how to overcome the struggles of pediatric hearing loss. My name is Melissa Tumblin, and I'm the founder of Ear Community, a non-profit organization.

My daughter, Ally, was born with microtia and atresia of her right ear. She is now seven years old. At times, it feels as if we have been on a roller coaster trying to grasp what it means to have hearing loss in one ear, and how to help Ally feel comfortable with her hearing loss. During Ally's first year of life, we were not provided much information about her hearing loss. Like many other families in the same situation, we struggled to obtain information about unilateral hearing loss – information that would have been critical from the very beginning. In fact, we didn't even realize that we were under-educated about her hearing loss until she was 11 months old, when I was online and stumbled across information about the potential benefits of a bone-anchored hearing system. I learned that she may be at risk for potential delays in her speech, language and communication, and that there were helpful services available that could help her for free, if she qualified.

Through Ear Community, I have spoken with many families who have experienced the same challenges. In addition, we struggle with trying to figure out where to fit in as a family with a child who has hearing loss, but is not completely deaf. We have come to realize that unilateral hearing loss can often be downplayed or overlooked both at home and in school settings. We are sharing our struggles and our successes, in the hopes of helping other families on their journey.

Unilateral Hearing Loss

Having unilateral hearing loss is like having an invisible disability. Although the person can still hear, communicate and respond in many situations, they are often missing out on much of what is said, especially in dynamic listening situations. People with unilateral hearing loss may have to work extra hard to figure out what they have missed in conversation. There may be a delay in their response time, as they are continually trying to make sense of what was just said. This can be exhausting, as their brain is compensating to fill in the blanks of conversations.

With children, it can be difficult for them to hear clearly in a classroom environment. Classrooms can be noisy, and sound can come from all directions. People with unilateral hearing loss may have trouble in noise, especially when noise is directed toward the better ear. They also have trouble with localization. A unilateral hearing loss can be detrimental to children as they are building their vocabulary skills during the critical years of development.

As the parent of a child with UHL, you are often told things like, “Your child still has one good ear, and that is good enough,” or “Your child has one hearing ear, so he or she can still hear.” These are all responses I have received from doctors, ENTs and some audiologists following the birth of my daughter. While these statements may offer relief in the beginning, they can later cause confusion or be misleading. For example, while I was relieved to find out that my daughter wasn't deaf and could still hear, I was under the impression that my daughter's hearing ear would somehow compensate for the ear that had hearing loss. I thought she was still able to hear everything just fine, but through one ear instead of two. In doing some research, I discovered that this was not the case.

Sininger & Cone-Wesson (2004) studied the way the right and left ears as well as the brain process sound. They found that the left and right ears do not work in exactly the same way. We used to think that it didn't matter which ear was impaired in a person with hearing loss. This study shows that it actually may have profound implications for speech and language development. I didn't realize how much of an impact unilateral hearing loss could have on a child. I went from thinking that my daughter was hearing at least 50% of everything in her hearing loss ear, to now realizing that maybe she'd be hearing less than 50% of everything, because of how our ears work independently.

As most of your know, hearing loss means more than a lack of volume; it isn’t that people with hearing loss simply need sounds to be louder. For example, I did not know that someone with unilateral hearing loss can struggle with localization – the ability to detect the direction where sounds are coming from. My daughter cannot detect a whisper, or know the direction someone is coming from when she hears approaching footsteps. She cannot discern where someone's voice is coming from when they are yelling for her. This raises a major safety concern, for example, when she is trying to cross a busy street. Frequently, when she hears a car approaching, she looks in the opposite direction.

I also was unaware that my child could potentially have delays in her speech, vocabulary and communication skills because of hearing in only one ear. After observing these delays in my own child, it became obvious to me that the impact of UHL is often misunderstood.

At first, it can be difficult to ascertain if your child is struggling with UHL, because not all children develop the same. Also, it is challenging for very young children to communicate what they are experiencing, because they do not yet possess language skills. In my experience, it has been valuable to listen to older children's experiences of what it is like to have unilateral hearing loss, because they can verbalize it effectively.

When my daughter was between three and five years old, I began to realize that she was struggling more than other children who had UHL, and more than some children who had hearing loss in both ears. After having my daughter evaluated by her audiologist, a neuropsychologist and a speech therapist, it was determined that in addition to my daughter's UHL, she also had an auditory processing delay and an issue with the processing of information. In other words, she couldn't hear conversations as well when there was background noise or multiple voices talking to her at once. When multiple people are trying to speak to us at once, in the presence of added sounds and background noise, it can be confusing for those of us who do not have hearing loss. For instance, in a restaurant, it can be challenging to hear what people are saying at your table, with all of the competing background sounds (e.g., clanking silverware, loud air conditioner, other conversations). I began to see how Ally could not hear me well in noisy situations (e.g., at the water park, the zoo, or the grocery store). I began to understand how my daughter's hearing loss was affecting her differently than her peers.

Research

In talking with other parents and comparing notes about our childrens’ unilateral hearing loss, it seemed to me that some of my daughter’s peers who had UHL in their left ear were not struggling as much as those who had hearing loss in their right ear. While doing some research on hearing loss, I read about how the right ear responds more to speech, while the left ear is more attuned to music. While my daughter always enjoyed music, she didn't begin speaking until age three. Going back to that earlier study (Sininger & Cone-Wesson, 2004), it was a revelation to me that my daughter's hearing loss in her right ear could contribute to her delay in speech.

In “Unilateral Hearing Loss, How Serious is it?” Dr. Jane Madell explains how hearing loss can impact children differently, depending on which ear has hearing loss. Dr. Madell indicates that hearing loss in the right ear can have more of an impact on speech and language, due to the way the brain is organized. This information helped me understand that children with hearing loss in their right ear could be at a higher risk for speech and language delays, since the left side of the brain is responsible for critical thinking where language skills are interpreted.

As I further researched, I read about how children with UHL may be at risk for struggling more in the classroom. In their article “Unilateral Hearing Loss in Children: Challenges and Opportunities” Oyler and McKay state: “Studies show that even before they enter school, children with unilateral hearing loss are at risk for speech and language delays. Although average age for first words was found to be within the normal limits (12.7 months), the average age for the first two word utterances was found to be significantly delayed in children with unilateral hearing loss.” I could see this happening in my daughter, who was showing signs of delayed speech by the age of three. Based on what our early intervention speech therapist was telling us, this was worrisome for me because my daughter was getting closer to attending preschool. Even though I now knew my daughter may have to work harder because of her hearing loss, I did not realize that she could struggle more with speech and learning because of having UHL.

A recent review article was published by Winiger, Alexander, and Diefendorf (2016). This review analyzed 69 articles and concluded that children with UHL and mild bilateral hearing loss have compromised speech recognition, may have poorer language skills and academic performance, and are more likely to have social, behavioral, and emotional issues.

As I continued my research, I was shocked to find out that 30% of students with unilateral hearing loss repeat a grade level by third grade. Furthermore, I learned that children with UHL were approximately 10 times more likely to fail a grade than their normal hearing peers. Children with a 30 dB hearing loss can miss as much as 25% to 40% of classroom discussion, and those students with a 35 to 40 dB hearing loss can miss as much as half. Much of this research comes from Drs. Fred Bess and Anne Marie Tharpe, as well as others, and references can be found in the course handout.

In order for parents to understand and cope with the child's hearing loss and the impact it can have on their child’s life, the challenges of hearing loss need to be explained from the very beginning. When my daughter was born, we did inquire about a hearing device with our ENT, but we were told that she was not a candidate for a cochlear implant. We thought this was our definitive answer – that she couldn't wear a hearing device. We assumed that she would be all right and manage to adapt because she had one good ear. Nothing was ever mentioned to us about a bone-anchored hearing system, a hearing device that she could have worn on a soft band/headband as early as two months of age to help her hear better. No one told us about early intervention services or that our child could be at risk for having speech and language delays due to having UHL.

The effectiveness with which information about UHL is communicated to parents affects how parents understand their child's hearing loss, and how it can impact their children. Providing information at the very beginning of the journey will enable parents to more successfully advocate for their children.

Parents’ Experiences, Case Examples

Critical information about hearing loss is needed for parents as early as when newborn hearing screenings are conducted. It is wonderful that we have a newborn hearing screening system in place to test for hearing loss, but it only works when the test is conducted correctly and when the results are explained in enough detail. I am frequently told by other parent that their child passed their newborn hearing screening but has hearing loss, or that their child has hearing loss but they were never informed about hearing devices.

In the support group that I run through my organization, several parents shared their experiences with their childrens’ newborn hearing screenings. I have been granted permission to share the following cases.

Nakita (mother of Lyla)

“Lyla was born without an ear canal in her left ear. Even though Lyla initially failed the newborn hearing screening, the staff continued to do the screening until the baby passed; they repeated the test up to three times until Lyla finally passed. While we were not sent to an audiologist or ENT, we eventually met with a pediatrician a week later. The pediatrician not only told us that Lyla may have hearing loss in her left ear, but he was surprised that no one at the hospital referred our family to see an ENT or audiologist for having a closed ear canal alone.”

I have been told many times by families that the hospital continued to conduct the newborn hearing screening until their child passed, as if it was a game that they were trying to get the result of “pass”. I am not sure if this is happening because of the lack of training of the people doing newborn hearing screening (e.g., in some cases maybe they are volunteers), or if they're just not educated enough due to budget cuts within the hospitals. When the very people who are performing these tests are not getting the correct results or aren't able to explain to a family what “referred” means, it's very concerning to me. When my daughter was born, and I was told that she had “referred”, I immediately asked what that meant. The three women that had come into the room with the newborn hearing screening cart told me that they were volunteers and they were not allowed to talk about the results with me because they don't have that kind of training. As they left I was worried about what it means to “refer.” Was my baby deaf? Could she hear? Was something else wrong? Those were the questions that ran through my mind. Later, the pediatrician did explain the results in somewhat more detail. However, we still had to wait two and a half more months to get answers, after finally being able to schedule an appointment with an ENT at our local children's hospital.

Amanda (mother of Noah)

“Noah was born with microtia and atresia of his right ear and he passed his newborn hearing test. Later, when he was a toddler, I realized he was having hearing and speech problems. We didn't find out he had atresia until he was almost five. Because of that newborn hearing screening, I felt that not only did it give a false sense of hope, but it delayed in getting the help he needed.”

Elisabeth (mother of Joshua)

“Joshua referred on his newborn hearing screening. It was explained to me that he had a unilateral hearing loss, but he can still hear well. Josh is now five years old and I have noticed over the years that he doesn’t mimic songs very well and is saying ‘what’ a lot. Even after having his hearing checked over the years, finally for the first time, I was told about a hearing device that could help him. If I hadn’t been told that he could still hear well, I wouldn’t have waited five years to get him the help he needed. No one ever said anything to us about getting him a hearing device.”

All of these children are now aided with a bone-anchored hearing system on a soft band headband and are thriving. It is important to realize how the results of newborn hearing screenings can be misleading, and how they influence parental decisions. Following the screening, it is critical that medical professionals inform families about the options for aiding their child, even if there is just unilateral hearing loss and the child is still under the age of five.

Here are some examples from families who have struggled to obtain information about hearing devices.

Janae (mother of Clark)

“My daughter, Clark, is now 21 months old and has microtia and atresia of her right ear. She does not have a bone-anchored system yet, but we are working on it. It is not ‘standard practice’ with her group of audiologists to treat unilateral loss with a bone-anchored system. We have been told that there is not enough research to support this, but I disagree. We have an appointment with her ENT on Wednesday, so we hope to get closer.”

Jay (father of Eden)

“My daughter, Eden, was born with unilateral hearing loss due to microtia/atresia in September (2010). At our first ENT visit ‘the best’ doctor in Omaha wasn’t going to mention a bone-anchored hearing system until I brought it up. Eden is being fitted for her first bone-anchored hearing system in 2 weeks.”

Casey (Texas)

“Once I found out about a bone-anchored hearing system, I called my hearing center and got a loaner within a month. The audiologists say the earlier the better, and nobody ever even mentioned a hearing device for babies.”

When hearing these stories, it disappoints me to know that not every hearing clinic seems to believe in or is offering the option of a bone-anchored hearing system as treatment for children with UHL, especially during the critical years of development. I don’t understand why the protocol is so inconsistent across hearing clinics. Once a child has a delay, that delay does not correct itself over night. This is why it is so important to be proactive and help a child hear better as early as possible, even when under the age of five. There should be a standard protocol that all clinics are required to follow, so that parents and families have the knowledge about what options (surgical and non-surgical) are available to them at all stages of their child’s development.

In 2013, a supplement to the 2007 position statement of the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing was released, that provides guidelines for establishing strong early intervention systems to meet the needs of children with hearing loss. This supplement states: “Research indicates that there are sensitive periods for the development of auditory skills and spoken language, specifically the first five years of a child's life are critical for development in these areas. To optimize the short time period of a child's life, families and infants with children who are deaf and hard of hearing should require the highest level of provider skills at the very beginning of a child's life.”

Per FDA regulations, a child cannot be implanted with a bone-conduction hearing device under the age of five. However, a younger child can still benefit from the use of a bone-anchored hearing device on a soft band headband. There are also other non-surgical hearing devices which can be worn by children under the age of five (in the ear and behind the ear).

When my daughter’s bone-anchored hearing system was first placed on her head (at 11 months old), I witnessed a dramatic difference. Ally had been a quiet baby since birth; however, when our audiologist switched on the hearing device (an Oticon Medical Ponto Soft Band), it was as if Ally had become a different child. Her eyes lit up, she whipped her head around and smiled when our audiologist whispered her name. I couldn't believe the reaction. Over the next few days, our early intervention therapist had also commented on how it seemed that overnight, Ally had become so engaged in her environment. Over the next weeks and months, Ally had begun babbling and cooing more, and began to make sounds that resembled words.

Psychological Effects of Unilateral Hearing Loss

I would like to touch on some psychological effects and challenges that children with UHL can experience.

Acting Out

Many children with hearing loss in general can have a tendency to act out, especially toward the end of the day. It is important for parents to understand that when children have hearing loss, they can act out without being hyperactive or having a diagnosis of ADHD/ADD. I know many families who have children who act out, but were never told that this is a side-effect of hearing loss. What parents need to know is that children with hearing loss, even UHL, have to strain to hear all day in every situation (in the classroom, in the lunch room, during sports or extracurricular activities, etc.). It is a lot of work for them to stay focused; at some point they just need a break during the day. Although some children with hearing loss may also have been diagnosed with ADHD or ADD, it is important to recognize when acting out is simply acting out, and nothing more.

Fatigue

Children who have UHL can suffer from fatigue. It can become very tiring struggling to hear all day. Their brains are working extra hard to fill in the blanks in conversation. Most of us know how tiring it can be when you're sitting in a conference. Perhaps the presenter isn't speaking very loudly and you're straining to hear them; or maybe the presenter has a heavy accent and your brain is struggling to understand what they are saying. As adults, we can get tired and might need a cup of coffee as a quick pick-me-up. Children, however, don't have the opportunity during school to choose when to take a break to collect themselves and re-energize. Snacks in school could help provide some needed energy, or additional breaks could be written into a child's school plan to help them recoup.

Learning Disabilities and Delays

As we've discussed, hearing loss can impact children in different ways. Some will have learning disabilities and delays associated with their hearing loss that can cause them to struggle more than others. Some children with hearing loss may be impacted by an auditory processing disorder, making it difficult to process spoken language and filter out noise. This can pose a challenge to quickly responding to questions and during conversation. Some children may experience additional challenges related to other disorders or delays that, when combined with hearing loss, may have an adverse effect on their ability to read and write.

Social Shyness

I have spoken to many adults with hearing impairment who were not aided when they were younger, who now say their hearing device has made them more social. When someone has unilateral hearing loss, it can be difficult to engage in conversation when you are not hearing everything. Some children will even avoid conversation because of hearing loss. Some will try and position themselves in places where they can hear better, but still end up struggling because they're not hearing everything. This makes them more inclined to not respond as much to questions or comments or participate in conversations. Some children are shy about participating in sports and games, because they are worried about not being able to hear well enough to participate equally with their peers.

Denial of Hearing Loss

Denial is also very common with children, and also adults, who have hearing loss. Everyone wants to fit in and be accepted. When someone has hearing loss, they may not want others to know. They may feel embarrassed and maybe they feel other people are judging them. They may not want to accept it themselves. Children do not always tell us everything; this includes not telling their teacher that they can’t hear well in the classroom. Often, children opt to keep their hearing loss quiet until they experience a situation that finally causes them to speak up.

Fear

Another emotion that children with UHL experience is fear. They may be afraid of not fitting in because of their hearing loss. They may be afraid to play sports or join in extracurricular activities. There can be a fear if their hearing loss changes, potentially getting worse. Parents can fear for their children’s safety. As I mentioned previously, my daughter struggles with localization (e.g., detecting the direction from which a car is coming). When I enter my daughter’s room in the morning, she cannot hear me if she is sleeping on her hearing ear. I worry about her getting older and attending college or having her own apartment. Will she not be able to hear an intruder or someone else coming in the house? Having unilateral hearing loss can cause fear, not only for the affected person, but for their families and loved ones as well.

The Benefits of Ponto

There are things that can help make life easier for children who have UHL. First, a bone-anchored hearing system can help children with UHL. Earlier, I mentioned how a parent from my support group had said that it was not standard practice with her group of audiologists to treat UHL with a bone-anchored hearing aid. They were told there is not enough research to support aiding unilateral hearing loss.

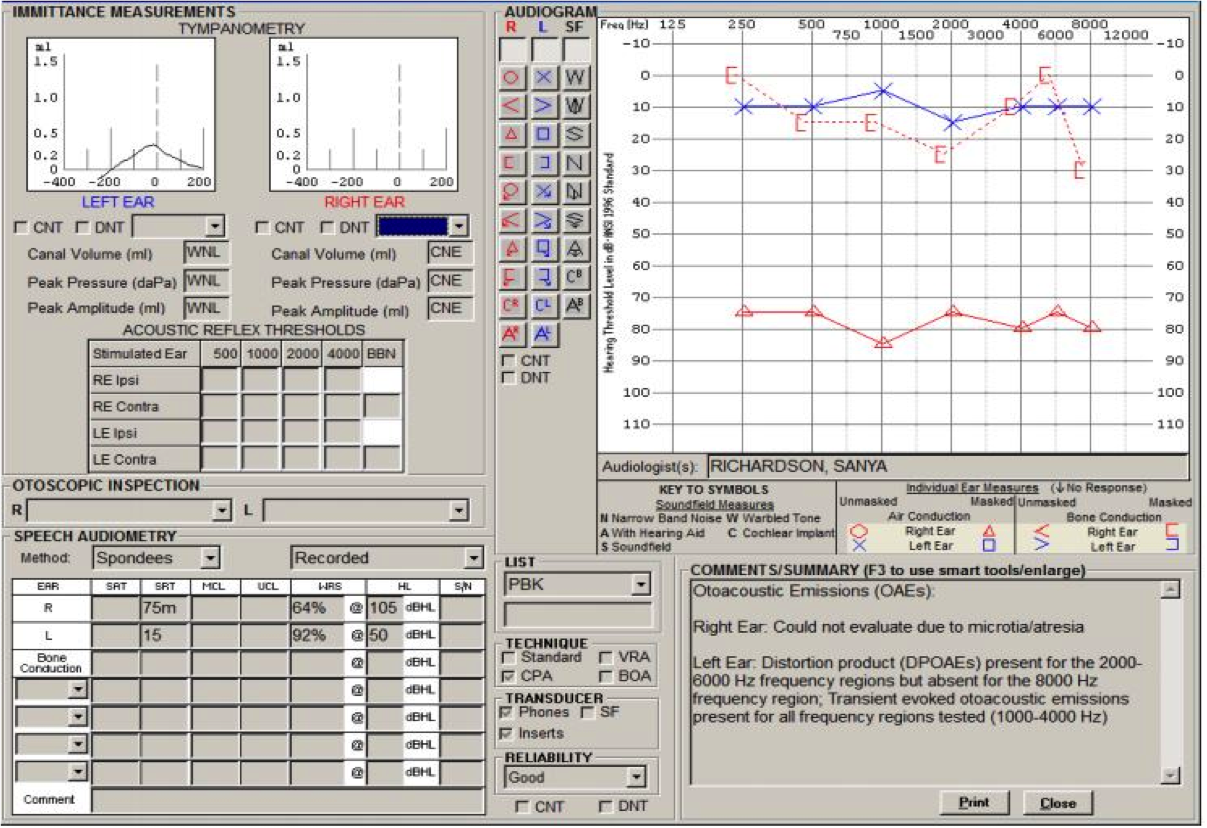

Here is my daughter's latest hearing test (Figure 1). As you can see, she has a severe hearing loss in her right ear; however, when aided with the Oticon Medical Ponto Plus, her hearing is restored within normal hearing range. After reading all of the research that I have found about UHL, about the critical years of development and discovering how a child with right ear hearing loss can be impacted more than someone with left ear hearing loss, it surprises me that others think there's not enough evidence or information to support being able to aid a child who has unilateral hearing loss with a bone-anchored hearing device.

Figure 1. Improvement in hearing with Ponto.

My daughter has been aided with the Oticon Medical Ponto Pro and the Ponto Plus since 11 months of age. She is now seven years old. When Ally was younger playing on the playground, if she wasn't wearing her bone-anchored hearing system, I would call to her and she would not come. She could hear me; however, she would look all over to figure out where my voice was coming from, whereas my other daughter (who does not have a hearing loss) would come directly to me. When Ally is aided with her Ponto, she comes directly to me. This makes me feel that she's safer when wearing her Ponto Plus.

Sometimes hearing loss can be subtle enough in a child that parents do not recognize they're struggling. When Ally began to wear her hearing device, we saw such a dramatic improvement, as compared to when she was unaided. Now that my daughter is seven years old I see how confident she is. She does not appear to be struggling in conversations when she is aided. She has learned how to advocate for herself and her needs (for example, when the device’s battery dies).

By wearing the Ponto Plus, my daughter is given the opportunity to be on par with her peers. In addition to aiding her hearing, the Ponto Plus is also compatible with FM in the classroom, helping her hear everything clearer, even when there is noise. When wearing her Ponto Plus my daughter is able to hear very soft sounds in the 15 to 20 dB hearing range. She also enjoys using the Oticon Medical Streamer to watch movies and play games on her tablet.

Additional Equipment and Services

There are many other products that can make life easier for someone with unilateral hearing loss. FM systems improve the signal-to-noise ratio and are beneficial for children with any type of hearing loss to hear better in noise. They are often used in school settings. The Oticon Medical Ponto Plus is compatible with FM systems, including the Oticon Amigo, to help children at school by being able to clearly hear the teacher’s voice directly in their ears. There is an FM system simulation on YouTube that I recommend watching to understand the benefit of FM systems.

Several years ago, I attended a conference where they provided the following scenario to help us understand what it may be like for a child with UHL to hear in a classroom. Imagine an empty and quiet school classroom. The sound level may vary, depending on if the floor is tiled or carpeted, how loud the air conditioner is, or if a window is open in the classroom. Now, add in children making sounds, like rustling paper, chewing gum, sharpening pencils, sliding chairs in and out. Also, take into consideration any other sounds that may be heard outside of the classroom, such as children walking down the hallway. While many of these extraneous sounds may not be occurring at the same time, they all add up; enough to prevent a student from clearly hearing what they need to hear (i.e., the teacher). A bone-anchored hearing system and an FM system used together can help a child hear their very best in the school classroom. Public schools usually will provide an FM system for free for use during school.

There are also many helpful services and informative support groups that can help make life easier when you have a child who has UHL or SSD. Every parent of a deaf or hard of hearing child should be told how an individualized educational plan (e.g., an IFSP, IEP, or 504 plan) can help their child receive the extra assistance necessary in order to thrive in school. Many parents are not aware that they can request an IEP for their child, even throughout their college years. They can develop the IEP to request that school staff wear an FM system, or that the child sit near the front of the classroom, if needed. They can ask to have an ASL interpreter, or to receive speech and occupational therapy services. From birth to age five, each state also has early intervention programs available to assist these children during the early years in receiving the help that they need from therapists and educational resources. Some can even help you obtain free hearing devices through early intervention providers. Support groups or meetings hosted by hearing loss organizations are also a great way to find helpful information and learn about other's experiences. Most of these services are usually free to families, regardless of income.

Helpful Tips and Information

It's not easy trying to keep a bone-anchored hearing system on a young child's head. Initially, children want to pull it off, but it's so important that the parent is persistent in keeping it on. Try to make it fun. When you put the hearing device on, play music, make it exciting. It's always better to have the device on the child's head while the child is in an upright position and not laying down. If you're terrified that your child is going to suck on the hearing device, or smear baby food on it, take it off of them while they're eating, and put it on when they're done. It's always important to remember to stay in control. If your child wants to take the hearing device off, consider setting a timer and say, “All right, but we're going to try it again in 20 minutes.” There are ways to help a child like their hearing device better. Personalize it to whatever the child likes (using stickers, sparkly gems, even yarn). They can even put a hearing device on a doll to make like the child feel like they're not alone.

Most audiologists are familiar with the “speech banana”. This tool alone helped me understand my child's hearing loss. The speech banana is used to describe the area where the sounds of speech appear on an audiogram. When phonemes are plotted out on an audiogram, they take the shape of a banana, therefore audiologists and other professionals refer to that area as the “speech banana.” The frequencies within the speech banana are critically important, because a hearing loss in those frequencies can affect a child's ability to learn spoken language. This very much helped me realize what sounds, pitches and words my daughter may or may not be hearing, because of her unilateral hearing loss.

At Ear Community, we have many other tools and resources. We have a section about surgery that outlines before and after surgical procedures for the implantation of a bone-anchored hearing device. It will show you how well scars heal after the surgery and explain about the healing process. There is a lot of helpful information on all the different types of hearing loss. Perhaps most importantly, for parents who are looking for support and information to take with them to their IEP meetings, we have many articles on unilateral hearing loss.

Considerations for Unilateral Hearing Loss

Mary Humitz, AuD: Sound is one of the most important sources of information for a child, especially during the critical years of development. Hearing speech sounds allows a child to learn to talk, which enables them to have conversations, to express needs and wants, and to ultimately connect with others. Sound matters, and that's why we have the very best technology available in the Ponto system, to protect this important source of information for a child.

Children need access to speech to develop their listening skills, to learn language and math, to listen to music, and to hone their social skills. Obstacles that make it difficult to listen and learn throughout the day include noise, distance, and poor acoustics. Children with normal hearing can struggle for full understanding of what is being said throughout the day; it's certainly apparent that kids with unilateral hearing loss are struggling as well. They need access to the best signal possible to deal with the same complex listening environments that they too must navigate.

Educational Considerations

Imagine that you are nine years old, you're in a science class, and you’re learning about volcanoes. The teacher is presenting new words that you may never have heard before (e.g., lava, eruption, magma, plate tectonics). Classrooms are noisy. Students whisper to each other about their plans during recess. The grounds keeper is cutting the grass, and the noise from the lawn mower is coming in through the window. There are all kinds of other classroom noises like books and chairs clanging. Even with normal hearing, it's difficult to concentrate on what the teacher is saying.

Classroom Listening Conditions

In today's educational environment, the cognitive demands have never been higher across all grades. Children must manage multiple tasks, such as reading and writing; controlling modern technology (e.g., tablets and laptops); attending to the teacher's voice, perhaps while engaging in group conversations with other students. While performing these tasks, they must simultaneously ignore irrelevant speech and extraneous noises, coming from inside and outside the class. Doing all of this places a significant load on their cognitive resources.

There are many studies that analyze the relationship between age and performance in adverse listening situations. One study in particular by Bradley and Sato looked at how speech recognition scores vary for different signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) across four different age groups. They looked at speech recognition scores by the age of the subject (ages 6, 9, 12 and adult). The subjects all had normal hearing. For an adult to score 80% correct in a speech recognition test, they need about a +4 SNR. In contrast, for a six-year-old to score that same 80%, they need an SNR of about +11. In other words, it's easier for the adult to score 80% as compared to a child, because an adult’s auditory systems can cope with more noise. Adults have a fuller vocabulary, and our auditory and cognitive processes are more integrated.

Children must learn to integrate multiple acoustic information sources; they need to do a number of things for them to be able to do this. It's a complicated process from detection through to processing. To do this efficiently requires an auditory and cognitive system that's well integrated. In general, young children are not as efficient as adults in detecting, processing and encoding this information. This skill improves with age and cognitive maturation.

Complex Acoustic Conditions

To reiterate, there are additional factors that compromise a child's ability to listen in complex conditions, including: brain immaturity, auditory inexperience, language unfamiliarity, unilateral or minimal hearing loss and cognitive or perceptual load.

There has been considerable research conducted that indicates that because young children have a limited vocabulary and immature language skills, they cannot use context to reconstruct what they may have missed due to hearing loss. The ability to control attention develops later, and is not as developed in the youngest of children. To be a good listener, especially in noise, children need that rich vocabulary. Listening in complex situations is compromised if you're a child that's unfamiliar with the language being spoken. Maybe English isn't the primary language spoken at home, yet the teacher is using English in the classroom. The speaker may have a heavy accent, where it's much harder to concentrate and to follow conversation. If you're a child with UHL, it's going to be much harder to cope in these complex environments. Greater effort is needed to listen in the classroom, or at home or out in the world, when there is a lot going on.

What a child with UHL may perceive as “noisy” is much different than what you and I might consider a noisy situation. You and I may think of a cocktail party, a loud restaurant or a concert as noisy situations. A kindergartner with UHL coloring a picture while the teacher is walking around the classroom may perceive that situation as noisy. The child is following directions from the teacher as the teacher is walking around the room; a child seated nearby is making a lot of noise rustling papers, rummaging through the crayon box. That can be a very noisy situation for a child with hearing loss. Or think of the older student in chemistry class concentrating on the experiment while listening to the teacher. All of a sudden, the careless student in the group drops a beaker on the floor. Or simply being at home when the child is practicing their spelling words, working at the kitchen table; but there's a lot of kitchen noise going on, the TV is on and little brother or sister are running around making noise. Listening in these complex situations takes considerable effort.

Pediatric Considerations

As audiologists, there are a number of considerations to think about when fitting children with amplification. As outlined by AAA Pediatric Amplification Guidelines from 2013, these considerations include the following:

- Children are learning language, and do not have the capacity to “fill in the blanks” for sounds that are not audible.

- Children spend most of their time listening to the speech of other children and women, which has greater high frequency content than that of males.

- Children who use hearing aids must develop the ability to use information acquired while hearing amplified, processed sound.

- Children have more demanding listening environments than adults for understanding speech. Enhancement of audibility is required either through increased level, increased SNR, or improvement of the listening environment.

A primary consideration must be children who wear devices, such as bone-anchored hearing systems. They develop speech and language through the use of these devices and need access to the very best signal processing available.

Ponto Plus Processors

Ponto provides clear access to speech, and its advanced features adapt to various changing environments. Ponto provides a full range of sound, capturing sounds at all levels, from soft sounds to louder sounds, without distortion or becoming too loud. It provides access to speech, even from soft-spoken talkers. A very important feature of Ponto Plus processors is extended bandwidth, which provides access to the full frequency range of speech, especially the important high frequencies. Increased low frequency information helps to provide better loudness sensation and voice quality. On an abutment, Ponto provides 38% wider frequency bandwidth than any other processor.

Ponto processes speech in the smartest way possible. The speech waveform is full of information that the child needs. Unique to Ponto, Speech Guard protects the subtle details of speech to make it easier to recognize and use. Noise management and directionality are also implemented in such a way to protect this vital speech information, while working to defeat the effects of background noise on speech understanding. Ponto is designed to enable sounds to be heard easily, without being muffled or distorted, and without feedback.

Bone Conduction: Direct Drive vs. Skin Drive

There are two approaches to bone conduction. The direct drive approach and the skin drive approach. For a child who is old enough for bone-anchored surgery (over the age of five years), the direct drive approach sends vibrations via direct route to bone (percutaneous). There is no muffling, there's no dampening – just direct sound. There's minimal physical sensation of the device when being worn. Tissue preservation surgery leaves only a small post visible where the processor connects. The Ponto system uses a direct drive approach. The other approach is the skin drive approach, where vibrations are sent through the skin and bone (transcutaneous). With the skin drive approach, there's a reduction in output and bandwidth due to skin attenuation. When wearing the processors with either approach, the direct drive or the skin approach, the processors are both worn externally and may be seen in the hair.

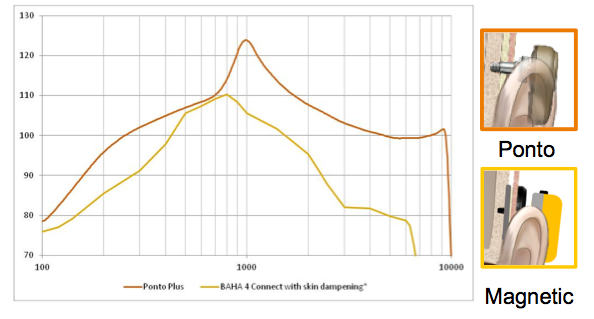

When a bone-anchored device is attached to a soft band headband, and it's compared to a bone-anchored device directly on an abutment, there can be as much as a 10 to 20 dB attenuation of sound in the mid to high frequency range. Figure 2 shows the output of a Ponto Plus device on an abutment (direct drive approach) and the output of a magnet device (skin drive approach). The direct bone conduction on an abutment provides significantly more output than the skin drive approach, both in the lower frequencies and in the mid and high frequency ranges. Remember, increased low frequencies help to provide better loudness sensation and voice quality and the high frequency range is important for speech perception, sound quality and understanding in noise.

Figure 2. Direct drive vs. skin drive approach.

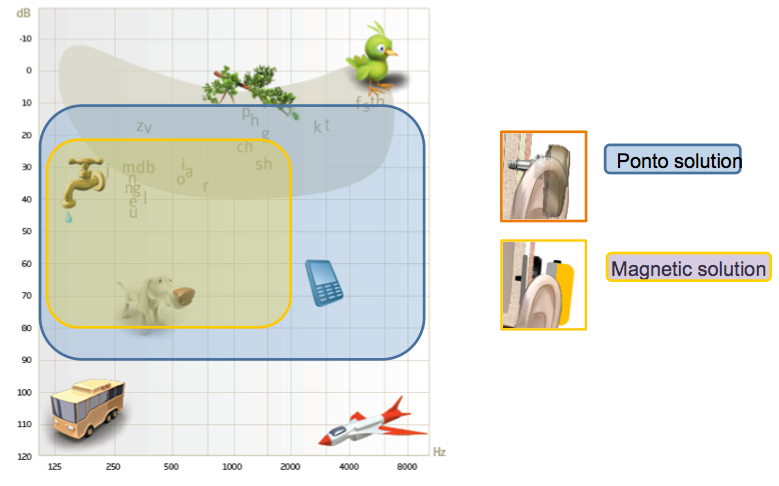

Another way to look at this is using the speech banana (Figure 3). When wearing Ponto on an abutment, what patients can hear is shown in the blue shaded area. A solution that attenuates due to the lack of direct vibrator to bone contact will greatly reduce the child's perception of important speech input, as shown in the yellow. The blue area is the direct drive approach and the yellow is the skin drive approach.

Figure 3. Audiogram with speech banana showing audible range for Ponto solution (blue) versus a magnetic solution (yellow).

Fundamentally, it gets back to why are children wearing the bone-anchored device to begin with? Children need to hear; they need to wear a solution with maximum audibility to develop their speech and language and communication skills, both inside and outside of school. Children need to wear a hearing solution that captures sound at all levels, from soft to loud, without distortion. We believe the soft band is the only choice before the age of surgery. When the child reaches the minimum age of surgery, the best hearing solution is provided through a direct drive approach.

Summary

In closing, children are affected differently by hearing loss. It is critical that parents are educated from the very beginning with information that will help them understand their child’s hearing loss. Every child deserves to receive help as early as possible. As communication skills improve, all areas of a child's life can be positively affected, including school performance, social relationships and self-esteem. As a result, children can achieve a higher level of success. That's what we believe we have the very best technology available in our Ponto system.

References

Joint Committee on Infant Hearing of the American Academy of Pediatrics. (2013). Supplement to the JCIH 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early intervention after confirmation that a child is deaf or hard of hearing. Pediatrics, 131(4), e1324-49. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0008

Sininger, Y.S., & Cone-Wesson, B. (2004, September 10). Asymmetric Cochlear Processing Mimics Hemispheric Specialization. Science, 305(5690), 1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1100646

Winiger, A.M., Alexander, J.M., & Diefendorf, A.O. (2016). Minimal hearing loss: From a failure-based approach to evidence-based practice. American Journal of Audiology, 25, 232-245. doi:10.1044/2016_AJA-15-0060

Citation

Humitz, M., & Tumblin, M. (2016, November). How to overcome the struggles of pediatric hearing loss. AudiologyOnline, Article 18560. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com