Introduction

The prevalence of tinnitus is significantly higher among hearing-impaired persons than in the normal-hearing population. Surveys (Seidman, Standring, & Dornhoffer, 2010; Davies, & El Refaie, 2000) have revealed that while 10-15% of the adult population as a whole suffers from tinnitus, as many as 70-85% of the hearing impaired population report tinnitus (Henry, Dennis, & Schechter, 2005).

Moreover, tinnitus has been found to have many of the same negative effects as hearing loss. For example, tinnitus often has a negative impact on a person’s physical and emotional well-being, causing increased stress levels, concentration problems, sleeping problems and reduced ability to hear. These in turn may have a negative effect on the person’s social life, personal relationships, and ability to work (Henry, et al., 2005; Kochkin, & Tyler, 2008).

Unfortunately, awareness of the possibilities of improving the symptoms of tinnitus via amplification appears to be very low among people with hearing impairment. In a recent large-scale study on tinnitus in the United States (Kochkin, 2007), 39% (more than nine million) of the self-acknowledged hearing impaired participants reported tinnitus to be the main reason why they did not purchase and use hearing aids.

The reasons for this low adoption rate are not known. One speculation could be that with milder hearing losses, tinnitus may create more problems in daily life than hearing loss, which is the lesser issue. Moreover, many people may be unaware that hearing aids can reduce the effect of tinnitus (Kochkin, 2007), and some may also fear that hearing aid use may in fact worsen their tinnitus.

Whatever the reasons, the low adoption rates among hearing aid candidates with tinnitus is worrisome, since the combination of tinnitus and untreated hearing loss may diminish people’s quality of life further than each condition separately. In addition, several well-documented tinnitus therapies, some of which involve hearing aids, are currently available.

A Novel Approach to Enticing People with Hearing Loss to Seek Treatment

The stigma associated with tinnitus has not been investigated to the same extent as the stigma associated with hearing loss. However, according to anecdotal reports, considerably less stigma is associated with tinnitus than with hearing loss. Thus, emphasizing the possibilities of achieving relief from the symptoms of tinnitus through hearing aid use may be an effective approach to motivating hearing impaired non-users of hearing aids to seek professional help.

This hypothesis was recently tested in a “free trial” advertising campaign in Switzerland. The campaign focused on the possibilities of achieving relief from the symptoms of tinnitus through hearing aid use rather than reducing hearing problems. The campaign offered a free trial of Widex CLEAR hearing aids with the Zen fractal tone feature to people with hearing impairment who were also suffering from tinnitus. The aim was twofold: to increase awareness of the possibilities of alleviating the effects of tinnitus by means of the Zen feature and/or amplification, and to entice potential hearing aid users to seek treatment for their hearing loss.

Using Sound Stimulation in Tinnitus Therapy

While the precise nature and causes of tinnitus are not yet fully understood, it is generally accepted that tinnitus involves increased neural activity, interpreted as sound by the brain, in the absence of acoustic stimulation (Seidman, et al., 2010; Searchfield, Kaur, & Martin, 2010; Sweetow, & Sabes, 2010). Numerous studies have shown that amplification can in itself alleviate the effects of tinnitus (Kochkin & Tyler, 2008; Searchfield, et al., 2010; Bo, & Ambrosetti, 2007). Precisely how is unknown, but it may be that tinnitus is aggravated by silence, as the brain tries to compensate for the neural stimulation it is being deprived of due to the hearing loss. Amplification increases neural activity and may thus succeed in reducing the brain’s compensatory activity. Another potentially important factor is that the amplification of background noise may partially mask tinnitus, or at least reduce the degree of contrast with silence (Sweetow & Henderson, 2010a).

There is no universally effective tinnitus treatment, but a number of treatment methods have been demonstrated to alleviate the negative effects of tinnitus. Current widely-used treatment methods typically include a counseling component combined with sound stimulation involving amplification, noise or music (Sweetow & Henderson, 2010a). The latter may contribute to reducing the negative effect of tinnitus by inducing a sense of relief from stress caused by tinnitus, or by diverting the person’s attention away from the tinnitus (Searchfield, et al., 2010).

This evidence for the beneficial effects of sound stimulation in terms of producing relaxation and attention diversion was the primary motivation behind the development of the Widex Zen feature. This feature utilizes a special hearing aid program capable of generating soothing tones and chimes as well as broadband noise. The program can be used to provide the sound stimulation element in the various forms of tinnitus management that rely on a combination of sound therapy and counseling.

Several studies have found a beneficial effect of the Zen feature when used in tinnitus therapy (Searchfield, et al., 2010; Kuk, Peeters, & Lau, 2010; Sweetow, & Henderson, 2010b ). For example, Sweetow and Sabes (2010) reported that 93% of the tinnitus patients in their trial experienced a reduction in tinnitus annoyance in one of the amplified conditions (i.e., with or without fractal tones or broadband noise) compared to the unaided condition. Furthermore, 69% of these participants experienced a lesser degree of tinnitus annoyance when listening to fractal tones vs. listening in the amplified condition alone.

Factors Known to Influence Hearing Aid Adoption Rates

There may be many reasons why many hearing aid candidates with tinnitus remain untreated. However, studies have looked at non-use of hearing aids in the general hearing-impaired population.

Several studies (Kochkin, 2007; Jenstad, & Moon, 2011; Kochkin, 2000) examining the reasons for hearing aid non-use among people with acknowledged hearing loss have revealed attitudinal factors such as self-perceived lack of severity of hearing loss, negative expectations towards hearing aids, and stigma, to be common barriers to hearing aid adoption. For example, in a recent large-scale MarkeTrak study by Kochkin et al. (2011), 69% of the non-adopters with acknowledged hearing loss reported that they thought their hearing loss was too mild to warrant the use of hearing aids. Sixty-eight percent also reported that negative expectations regarding the benefits and handling of hearing aids had influenced their decision not to buy hearing aids, and 39% reported stigma to be a reason. Thus, many people with diagnosed and acknowledged hearing loss may still require additional enticement to seek out a hearing aid solution.

Another important factor in hearing aid adoption in the hearing impaired population in general is first experience with hearing aid use. In Kochkin et al.’s MarkeTrak VII study (2007), 12% of the total non-adopter population reported a negative experience with a past trial to be one of the reasons for their decision not to purchase hearing aids. The proportion increased to 20% when they examined the subgroup with a severe degree of hearing loss. Poor benefit, amplification of background noise, feedback, discomfort and poor sound quality were among the most common complaints in the latter group. Similar findings were obtained in the MarkeTrak V (Kochkin, 2000) study, which is a large-scale investigation of the reasons why some hearing aids are not worn or used after purchase. No need for help, poor benefit, background noise/noisy situations, poor sound quality, feedback problems, and difficulty with volume control adjustments were among the top reasons given by people for not using their hearing aids.

On the basis of a literature review, Kochkin et al. (2011) listed a set of criteria that are particularly important for the success of hearing aid use with tinnitus patients. These include best practice procedures during the fitting process, design aspects, and professional service, specifically:

- Real-ear measurement verification of hearing aids

- Objective benefit measurement

- Customer satisfaction measurement

- Loudness discomfort measurement

- Hearing aid fit and comfort

- Sound quality

- Attributes of the hearing care professional

The first challenge in providing benefit or success with hearing aids for tinnitus patients, however, is persuading them to seek professional help. Then, these factors may be considered in the hearing aid selection, manufacturing, fitting and follow up processes.

Free-Trial Campaign in Switzerland

To create awareness of the possibilities of achieving relief from the symptoms of tinnitus through amplification and/or the Zen feature, a free-trial campaign was recently launched in Switzerland by an independent chain of clinics. The campaign offered a free trial of Widex CLEAR hearing aids with the Zen feature for a period of four weeks to hearing-impaired people with tinnitus. Participants were given the option of purchasing the devices after the trial. Advertisements were placed in local newspapers inviting people to participate in a free trial of the Widex CLEAR hearing aids. The response was excellent. Participating clinics reported receiving 50% more patient contacts than usual over a period of three months. There was also considerable interest from people with tinnitus with normal hearing, even though the advertisements specifically stated that prospective candidates must have a hearing loss to be included in the trial.

Subjects

Of the roughly 200 hearing-impaired persons included in the trial, 50% did not own hearing aids. Given the low hearing aid adoption rates among hearing-impaired persons with tinnitus in the US reported by the Better Hearing Institute (Khalfa, Bella, Roy, Peretz, & Lupien, 2003), the fact that such a large proportion of the hearing-impaired tinnitus sufferers in the trial was perhaps not surprising. Moreover, the vast majority had a relatively mild degree of hearing loss.

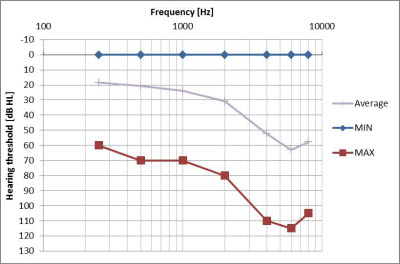

Eighty percent of the non-owners were men and 20% were women. Their ages ranged from 31 to 84 years (mean age: 60 years). The range of hearing losses represented in the trial is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Audiometric range for the participants in the trial (averaged across the left and right ears).

Hearing instruments

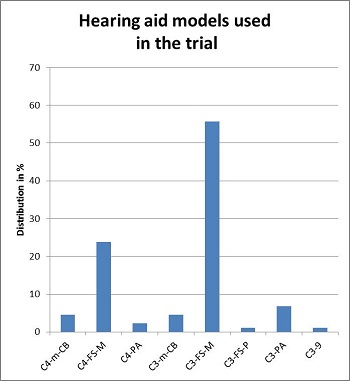

Participants were fitted with wireless CLEAR440 (high-end) or CLEAR330 (mid-range) hearing aids (either the Passion (PA), Fusion (FS), m-CB (m-model with ClearBand), or 9 model) in accordance with their audiometric configurations and personal preferences. The vast majority (80%) were fitted with the CLEAR440 or CLEAR330 Fusion models with an M-receiver (C4-FS-M) or C3-FS- M, which is suitable for people with minimal to moderately-severe hearing loss.

Details of the hearing aids used in the trial are shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Hearing aid models used in the trial. Participants were fitted with the Passion (PA), Fusion (FS), m-CB (m-model with ClearBand), or 9 models in the CLEAR440 (C4) or CLEAR330 (C3) hearing aid series.

One of the unique features of the CLEAR hearing aid family is the availability of the InterEar-Zen program. This is an optional listening program that can provide the wearers with access to randomly-generated fractal music and broadband noise. As mentioned earlier, tinnitus and stress are highly correlated. When stress increases, the perception of tinnitus increases, and when tinnitus increases, stress increases. However, music has been shown to be effective in reducing stress (Khalfa, et al., 2003; Scheufele, 2000). Musical characteristics, such as a relatively slow tempo (60-70 beats per minute), a relatively low pitch, predictability, and lack of emotional content, have been established as having a relaxing, rather than alerting effect (Sweetow, & Henderson, 2010b). Fractal technology (Zen tones) ensures that no sudden changes appear in the tonality or tempo of the music generated in the Zen program. They repeat enough to sound familiar, but vary enough to not be predictable. The tones, which sound somewhat like wind chimes, are thus pleasantly neutral, and incorporate the properties of music that have been proven to be most relaxing. By delivering these sounds in accordance with the individual’s hearing loss and in an inconspicuous manner via high fidelity hearing aids, both hearing loss and stress management can be addressed.

Another unique feature in Widex hearing aids is SmartSpeak. SmartSpeak is a verbal messaging system which aims to make it easier for the users to control their hearing aid through verbal instructions recorded in the user’s native language. For example, SmartSpeak will alert the users when the battery is running low, and inform them of the program mode they are in when they change listening program.

Results

Participants completed a questionnaire on their experiences with the Zen feature and the CLEAR hearing aid at the end of the four-week trial. The results for the Zen feature indicated a high degree of satisfaction with the feature among the hearing aid candidates with tinnitus. Sixty-nine percent enjoyed listening to the Zen tones, and 54% reported the Zen feature to have had a definite effect in terms of helping them to relax. These data will be reported in more detail in a future publication.

The participants also answered a number of questions regarding their experience with the hearing aids during the trial period. The participants replied to a number of questions regarding some of the most influential factors in hearing aid adoption, including hearing aid sound quality, speech perception ability in difficult environments, localization ability, and ease of use.

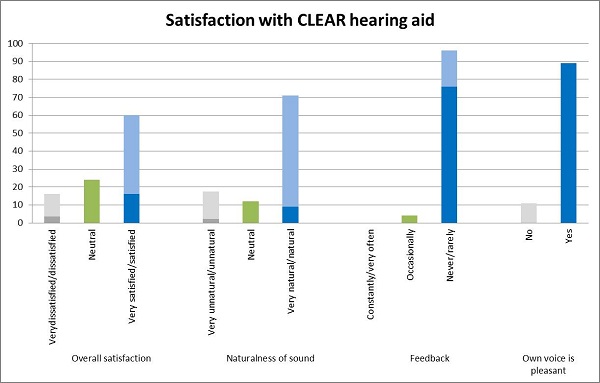

Satisfaction with hearing aid. User satisfaction ratings for the CLEAR hearing aids are shown in Figure 3. The majority of the hearing aid candidates with tinnitus appear to have had a good first experience with the aids, with 84% of the users reported being either satisfied, very satisfied or neutral in terms of overall satisfaction, while only a small proportion of the users (16%) were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the aids.

Satisfaction with sound quality. Data show that the sound quality of the hearing aid can be decisive for whether a hearing aid is accepted or rejected by a first-time user. The participants were asked to evaluate the sound quality of the hearing aid on a number of aspects, including naturalness of sound, occurrence of feedback, and quality of own voice. The vast majority (71%) responded that they perceived the sound quality to be natural or very natural, and that their own voice had a pleasant sound (89%). The users had few problems with feedback. Eighty-six percent reported that feedback occurred rarely or never, while 10% reported occasional occurrences. None of the participants reported very frequent or constant occurrence of feedback.

Figure 3. Hearing aid candidates’ overall satisfaction with the hearing aid, perceived naturalness of sound quality, problems with feedback, and perceived pleasantness of own voice.

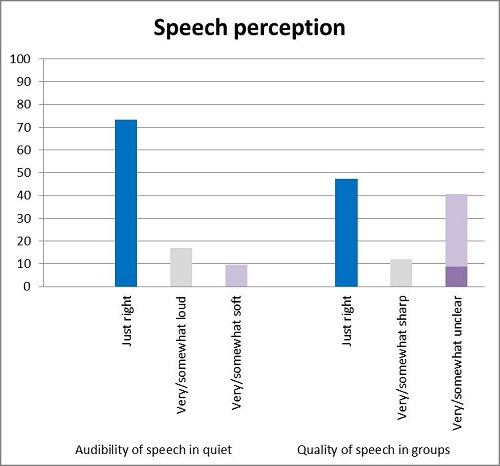

Satisfaction with speech perception. A strong motivation for hearing aid candidates is the desire to achieve better speech perception. The hearing aid candidates were therefore asked to evaluate the CLEAR hearing aid’s effectiveness in a relatively optimal speech perception situation in quiet surroundings, as well as in one of the, for hearing-aid users, most challenging situations, when several people in a crowd are talking at once. Seventy-five percent of the users responded that the audibility of speech was just right in quiet surroundings, while a small minority thought it was either somewhat soft (10%) or somewhat loud (17%). Not unexpectedly, speech perception was more challenging when several people spoke at once. Forty-seven percent of the users reported speech clarity to be just right in that situation.

Figure 4. Audibility of speech in quiet situations (left) and clarity of speech when several people talk at once (right).

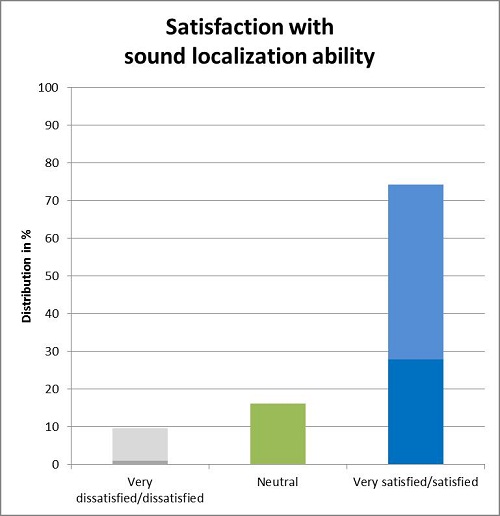

Satisfaction with sound localization ability. User reports on self-perceived sound localization ability were generally positive (Figure 5). The vast majority (74%) were satisfied or very satisfied with their own ability to determine where sound was coming from when wearing the CLEAR hearing aids. Sixteen percent responded that they were neutral, while 10% were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with their own ability to localize a sound source.

Figure 5. Satisfaction with own ability to localize a sound source.

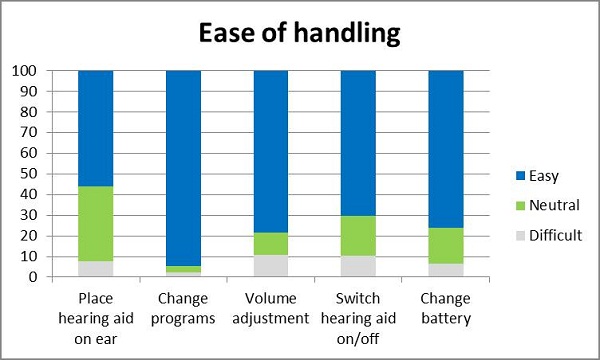

Satisfaction with ease of use. As discussed above, hearing aid candidates often reject hearing aids if the devices are perceived to be difficult to manage. Much effort has therefore been put into designing the CLEAR hearing aids to be user-friendly and straightforward to use. The results from the survey of trial participants (Figure 6) indicate that the hearing aid candidates did indeed find the hearing aids easy to manage. Ninety-five percent reported change of program to be easy, and 79% found it easy to adjust the volume. Change of battery and switching the hearing aids on/off were considered easy by 76% and 70% of the participants, respectively. Placing the hearing aid on the ear was the most challenging activity. Fifty-six percent reported this to be easy, while 37% responded that they were neutral, and 8% replied that they found it difficult.

Figure 6. Perceived ease of the basic activities of placing the hearing aid on the ear, changing listening program, adjusting the volume, switching the hearing aid on/off, and changing the battery.

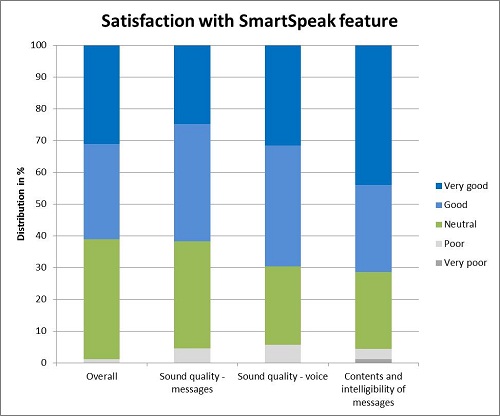

The participants were also asked a number of questions regarding the verbal messages of the SmartSpeak feature. Participants rated their overall satisfaction with the feature, with the sound quality of the messages and the speaker’s voice, and with the contents and intelligibility of the verbal messages. The results are shown in Figure 7. Satisfaction was high on all four parameters: 61%- 71% of the ratings were positive (Good/Very good), 24-38% of the ratings were neutral, while less than 10% were in the negative categories of Poor/Very poor.

Figure 7. Evaluation of the verbal messages of the SmartSpeak feature. Participants rated their satisfaction with the feature overall, with the sound quality of the messages and the speaker’s voice, and with the contents and intelligibility of the messages.

Conclusion

The results from the recent free-trial campaign in Switzerland indicate that emphasizing the tinnitus treatment possibilities of hearing aids may be a novel avenue to persuading hearing-impaired non-owners with tinnitus to seek treatment.

The strong interest from hearing impaired non-owners of hearing aids suggests that tinnitus may be a greater issue than the hearing loss. Thus, focusing on the possibilities of achieving relief from the symptoms of tinnitus rather than the hearing loss may be an effective way to persuade skeptical non-users with hearing loss to try hearing aids.

Furthermore, the results from the user trials with the CLEAR hearing aids suggest that once the non-owners with tinnitus have been persuaded to try hearing aids, the majority are satisfied with the experience.

References

Bo, D. L., & Ambrosetti, U. (2007). Hearing aids for the treatment of tinnitus. Progress in Brain Research, 166, 341-345.

Davies, A., & El Refaie, A. (2000). Epidemiology of tinnitus. In R.S. Tyler (Ed.), Tinnitus Handbook (pp. 1-24). San Diego: Singular Publishing Group.

Henry, J. A., Dennis, K. C., & Schechter, M. A. (2005). General review of tinnitus: Prevalence, mechanisms, effects, and management. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48, 1204-1235.

Jenstad, L., & Moon, J. (2011). Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to hearing aid uptake in older adults. Audiology Research, 1(e25), 91-96.

Khalfa, S., Bella, S. D., Roy, M., Peretz, I., & Lupien, S. J. (2003). Effects of relaxing music on salivary cortisol

level after psychological stress. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 999, 374-376.

Kockhin, S. (2000). MarkeTrak V: “Why my hearing aids are in the drawer”: The consumer’s perspective. The Hearing Journal, 53(2), 34-41.

Kochkin, S. (2007). MarkeTrak VII: Obstacles to adult non-user adoption of hearing aids. The Hearing Journal, 60(4), 24-51.

Kochkin, S., & Tyler, R. (2008). Tinnitus treatment and the effectiveness of hearing aids: Hearing care professional perceptions. Hearing Review, 15(13), 14-18.

Kochkin, S., Tyler, R., & Born, J. (2011). MarkeTrak VIII: The prevalence of tinnitus in the United States and the self-reported efficacy of various treatments. Hearing Review, 18(12), 10-27.

Kuk, F., Peeters, H., Lau, C. (2010). The efficacy of fractal music employed in hearing aids for tinnitus management. Hearing Review, 17(10), 32-42.

Scheufele, P. M. (2000). Effects of progressive relaxation and classical music on measurements of attention, relaxation, and stress responses. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23(2), 207-228.

Searchfield, G. D., Kaur, M., & Martin, W. H. (2010). Hearing aids as an adjunct to counseling: Tinnitus patients who choose amplification do better than those that don’t. International Journal of Audiology, 49(8), 574-579.

Seidman, M. D., Standring, R. T., & Dornhoffer, J. L. (2010). Tinnitus: Current understanding and contemporary management. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology, 18(5), 363-368.

Sweetow, R. W., & Henderson, S. J. (2010a). An overview of common procedures for the management of tinnitus patients. The Hearing Journal, 63(11), 11-15.

Sweetow, R. W., Henderson, S. J. (2010b). Effects of acoustical stimuli delivered through hearing aids on tinnitus.Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 21(7), 461-473.