Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Define tinnitus and describe the main causes.

- Name at least four tinnitus assessment tools and describe their purpose in tinnitus management.

- Describe the difference between tinnitus treatment and tinnitus management.

Introduction

Before we begin, please note that this course is not designed to discuss clinical protocols for tinnitus. Rather, it is intended to be a general overview of tinnitus with a broad array of details for a practitioner who may be interested in getting started with the management of tinnitus patients. We're going to start with some basics to help spark interest in the overall topic of tinnitus. In Part I, we will cover the definition, epidemiology, causes, demographics and pathophysiology of tinnitus. In Part II, we will review an interesting study related to activities that affect those who suffer with tinnitus. In Part III, we'll look at tinnitus assessment, management with sound therapy, and we'll finish up with a few case studies.

Why Talk About Tinnitus?

Tinnitus management is becoming more readily available in today's clinical hearing aid practices. Hearing care professionals should be prepared and up-to-date on the current tinnitus technology. In addition, sound generator options built directly into hearing aids are becoming more common. For example, Sonic now provides a hearing device with a sound generator in our latest hearing aid, called Tinnitus SoundSupport.

Tinnitus affects a wide array of people. Notable historical figures who suffered from tinnitus include Ludwig von Beethoven, Charles Darwin, Michelangelo and Vincent van Gogh. Additionally, the following celebrities also have tinnitus: Alex Trebek, Barbra Streisand, David Letterman and Liza Minelli. From past to present, as well as looking into the future, tinnitus remains a universal condition. It can strike anyone, anywhere, at any time. As a hearing care professional, are you prepared to treat patients with tinnitus?

Part I: Tinnitus Overview

Definition

Tinnitus, or ringing in the ears, is a sensation of hearing ringing, buzzing, hissing, chirping, whistling or other sounds. In rare cases, the sound beats in sync with your heart, which is also known as pulsatile tinnitus. Tinnitus itself can be intermittent or it can be continuous and it can vary in loudness. It is often worse when background noise is low. A patient may be most aware of it at night when trying to fall asleep, or if they are in a quiet room. It is important to note that tinnitus itself is not a disease. Rather, tinnitus is a symptom of an auditory disorder.

Classification

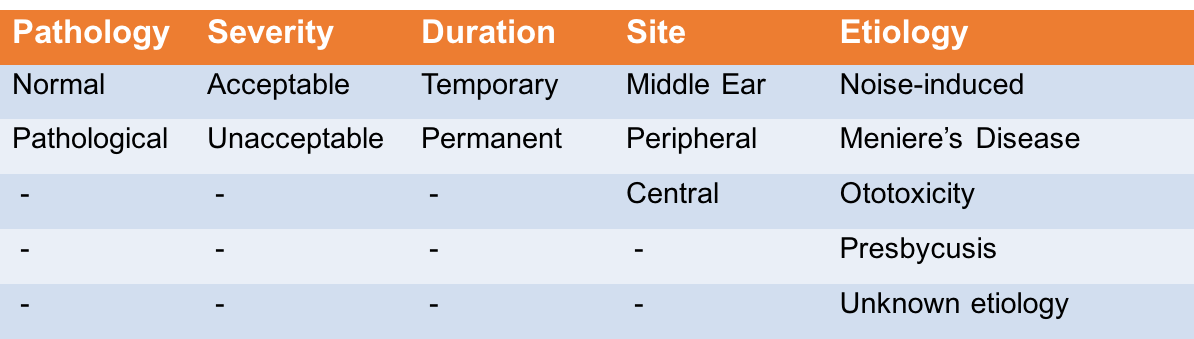

In order to help patients manage their tinnitus, we have to know how to classify it. Tinnitus is not black and white. It cannot be classified with a single category of being either "present" or "absent". Dauman and Tyler (1992) devised a tinnitus classification system (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Tinnitus classification system.

When taking a case history from a new patient, it's helpful to keep five categories in mind.

- Pathology: Normal tinnitus is experienced by nearly everyone at some point, lasting less than five minutes and less than once a week. Pathological tinnitus lasts longer than five minutes, occurs more than once a week, and is often accompanied by hearing loss.

- Severity: If it is acceptable, it doesn't bother the patient much. If it is unacceptable, it disturbs the patient.

- Duration: Temporary tinnitus lasts a short while, perhaps after attending a loud concert or a noisy event, or even after taking certain medications. Permanent can be either continuous or intermittent over time.

- Site of dysfunction: This may be in the middle ear, or it could be sensorineural.

- Etiology: This classifies the cause of the tinnitus, whether from noise, disease, medication or age.

Epidemiology

According to the American Tinnitus Association, tinnitus is a condition that affects millions of people. In fact, the US Centers for Disease Control estimate that while 50 million Americans experience it, 20 million find it burdensome and two million find it debilitating. In total, that's approximately 15% of the general population. It is important to note that the prevalence of tinnitus increases in the clinic population. That is because tinnitus is a common symptom of patients seeking treatment for ear and/or hearing-related concerns (Spoendlin, 1987).

Another segment of our population greatly affected by tinnitus is service men and women in the US Military. According to 2011 data from the American Tinnitus Association, over 800,000 veterans experience tinnitus. In addition, over 700,000 of our veterans are affected by hearing loss. Those two conditions combined make up more than half of the top service-related disabilities for that particular year.

Causes

Hearing loss is the most common cause of tinnitus. Eggermont (2012) noted that the prevalence of tinnitus increases more so from noise-related hearing loss than from age-related hearing loss. Beyond hearing loss, there are many other causes of tinnitus, both related and unrelated to the ear.

According to the Mayo Clinic, every section of the ear can contribute to tinnitus. Starting with the outer ear, some contributing factors may include wax impaction, or even potentially a foreign body touching the tympanic membrane. Contributing factors associated with the middle ear can include a middle ear infection, eustachian tube dysfunction, vascular changes, otosclerosis, benign tumors and spasms. Lastly, factors relating to the patient's inner ear (and even retrocochlear causes) may include hearing loss, a variety of vestibular conditions, or possibly even an acoustic neuroma or a vestibular schwannoma.

There are numerous other causes of and contributing factors to tinnitus, such as blood vessel disorders, injuries and medications. Depending on the suspected cause, further testing may be required to identify the source and also the best course of treatment. Many of the aforementioned causes warrant diagnosis, treatment, and/or monitoring by a medical doctor.

Demographics

Because tinnitus has no cure, it is important to find out which groups of people are more susceptible to tinnitus than others. We should have a good grasp of all possible risk factors for groups of people, to better understand how it may present in clinic populations, and also to better educate the public.

Researchers examined the relationship between risk factors and also self-reported tinnitus in over 14,000 participants in a nationally represented database (Shargorodsky et al., 2010). Not surprisingly, their analysis confirmed that individuals with hearing loss, persons exposed to loud recreational or occupational noise, and adults between the ages of 60 to 69 are more likely to have frequent (i.e., daily) tinnitus. The study also revealed that non-Hispanic whites, adults with hypertension, former smokers, and those with generalized anxiety disorder were more likely to experience tinnitus than the general population.

According to a review article by tinnitus researcher, Marc Fagelson, he reports that over 50% of tinnitus sufferers have a comorbid psychological injury or illness, such as PTSD, depression, anxiety, OCD or stress (Fagelson, 2014). Clearly, if you treat a diverse population of patients in your clinic, it is to your benefit to have an awareness of these at-risk subgroups, so you can further be alerted to their likelihood of reporting tinnitus.

Pathophysiology

Now, we will review the functional or anatomic changes associated with tinnitus, as compared to a normally working system. For the purposes of this course, we will keep our focus narrow, looking only at hearing loss, and why a loss of hearing sensitivity would cause a phantom sound in the ear.

We need to start this discussion with a simple definition of spontaneous activity in the nervous system. As explained in the Tinnitus Handbook (Tyler, 2000), spontaneous activity refers to "involuntary neural processes that occur within the brain". For example, it can be thought of as background sounds arising from active hair cells in the cochlea, action potentials firing in the auditory nerve, or EEG activity.

The one thing that we want to understand is that spontaneous activity is a normal occurrence in the auditory nervous system, but we don't hear it because we typically adapt to it. However, if spontaneous activity is a completely normal occurrence in the auditory nervous system, why are we discussing it? The reason is because when something alters typical spontaneous activity (i.e., the baseline state), that is when it may lead to tinnitus.

The following chain of events occurs:

- When outer hair cell (OHC) damage occurs in the cochlea (due to aging or noise exposure), the spontaneous activity in a portion of those auditory nerve fibers is altered.

- Neural changes start to occur.

- Synapses at higher neural levels reorganize and become re-tuned.

- These synapses respond to the edge (border) of the remaining healthy parts of the cochlea.

- The re-tuned neurons continue to fire, even in the absence of sound.

- This produces a pitch similar to the frequencies bordering the hearing loss, close to the frequency of maximum hearing loss.

- Excessive neural noise is heard as tinnitus sound.

This is one explanation as to why high-frequency hearing loss often causes tinnitus that is also high-pitched in nature.

Part II: Study Snapshot

In this next section, we will highlight a study that examined what activities can influence a patient's tinnitus. We have observed that just because a patient has tinnitus (perhaps stemming from a permanent hearing loss), it does not stay consistent 100% of the time. Rather, it can get better or it can get worse on any given day, or it can even fluctuate and change throughout the day. Pan, Tyler, Ji, Coelho, and Gogel (2015) conducted a study to investigate differences between patients that may cause their tinnitus to be better or worse. The purpose of this study was to identify the top activities that influence tinnitus for patients, and also to discover if any trends exist among variables.

Method

Within this study, a total of 258 patients were asked to answer two questions:

- When you have your tinnitus, which of the following makes it worse?

- Which of the following reduces your tinnitus?

These were the top five reasons given as to what makes a patient's tinnitus worse:

- Being in a quiet place (47.7%)

- Emotional or mental stress (36.4%)

- Having just recently been in a noisy situation (36.0%)

- Being in a noisy place (32.2%)

- Lack of sleep (27.1%)

Other things that increased a patient's tinnitus included: shooting guns or rifles; excitement; relaxation; sudden physical activity; alcohol intake; drugs/medicine; coffee and tea consumption; changing head position; different foods; and smoking.

The following top seven reasons were given as to what reduces a patient's tinnitus:

- Nothing makes it better (30.6%)

- Being in a noisy place (22.5%)

- Other (21.7%)

- Relaxation (14.7%)

- Not sure (14.7%)

- When first waking up in the morning (8.9%)

- Being in a quiet place (7.4%)

It's interesting to note that being in a noisy place and being in a quiet place were included on both lists as things that make a patient perceive their tinnitus to be both better and worse.

Results

As a result of this study, researchers found that:

- Things that made tinnitus worse included:

- Being in a quiet place (48%), stress (36%), being in a noisy place (32%), and lack of sleep (27%)

- Almost 6% of patients suggested coffee/tea and 4% said certain foods made their tinnitus worse

- Things that made tinnitus better included:

- Noise (22%)

- Relaxation (15%)

- Trends indicated that:

- For those whose tinnitus is not worse in quiet, it is usually not reduced by noise

- For those whose tinnitus is not worse in noise, it is usually not reduced in quiet

Conclusion

From this study, it was made evident that there is no "one size fits all" approach to treating tinnitus. Each patient presents differently. In fact, there can be big differences within a single patient as their tinnitus fluctuates during daily activities. We will see some examples of this coming up in our case studies.

Part III: Tinnitus Assessment and Management

In this section, we will review the basic concepts related to both topics of measuring and managing tinnitus, and then we will look at three case study examples.

Assessments

Health insurance will reimburse for a tinnitus assessment. The CPT code is 92625 for a binaural exam. However, we don't want the ability to be reimbursed to be the only reason we conduct a tinnitus assessment. Tinnitus assessment truly is an integral part of a tinnitus management plan.

In an assessment, we are going to characterize and quantify the type of tinnitus that the patient is experiencing. We also will document the condition, which may be necessary for medical legal cases, and it also helps to determine the best way to manage the condition. In addition, assessing tinnitus is reassuring for patients, as some people with chronic tinnitus may exhibit stress, anxiety, insomnia, and other intense emotions related to their condition. The ability to measure or quantify tinnitus will validate not only that the tinnitus is real, but also that there is potential hope to treat a sound that only they can hear (Tyler and Baker, 1983).

A tinnitus assessment begins like any other hearing evaluation. First, you want to perform a complete diagnostic test battery which includes pure tone and speech audiometry. Next, we move on to speech audiometry with speech recognition thresholds and word recognition. Then, we have tympanometry and acoustic reflexes, and as well as otoacoustic emission testing.

Following the routine clinical exam, you can also look at further tests that can be administered with a clinical audiometer, or with other specialized equipment such as the MedRx Tinnometer. This equipment is used to measure the sound, the pitch and the volume of the patient's tinnitus.

Common assessment tests include the following:

- Pitch Matching: Pitch matching is a useful test in identifying the center pitch of a patient's perceived tinnitus. In performing this test, common tinnitus tones or sounds are presented to the patient and the patient then identifies the sound that most closely matches the tone or sound that they hear in their ear. This test is particularly useful in providing a baseline for sound therapy.

- Loudness Matching: Loudness matching ascertains the loudness of the patient's perceived tinnitus. In this test, the patient is presented with two different tones and then they must choose the one that is closest to their tinnitus. The intensity is recorded in dB SL.

- Octave Confusion Test: Tests for octave confusion confirms the octave of the patient's tinnitus. In performing this test, a tone is presented at one octave above and one octave below the selected frequency in an effort to confirm the correct octave. This test is useful, as it is found that patients sometimes confuse the pitch of their tinnitus with a tone one octave above it or below it.

- Minimum Masking Level: To find a patient's minimum masking level, a masking signal is presented in ascending steps until the patient reports that their tinnitus is no longer detectable. This point at which it becomes no longer detectable is then recorded as the minimum masking level.

- Loudness Discomfort Level: Loudness discomfort level is utilized to find the uppermost limit at which a presented sound becomes uncomfortable for the patient. This measurement truly has many clinical uses, but it is especially useful for a patient who may have reduced dynamic range or hyperacusis.

- Residual Inhibition: In the test for residual inhibition, the clinician determines that the patient's perceived tinnitus can be reduced with sound. In the testing, a masking signal is presented to the ear for about 60 seconds, and it reveals if the tinnitus is completely or partially reduced, or in some cases there is no change, or it is increased.

Subjective Questionnaires

The following questionnaires can be used as part of a tinnitus assessment:

- Tinnitus Handicap Inventory

- Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire

- Tinnitus Functional Index

- Tinnitus Severity Index

We know that the severity of a patient's tinnitus does not necessarily correlate with the degree or the type of hearing loss (Perry and Gantz, 2000). We need to get a good feel for the patient's perception of the severity of the tinnitus, because again, we cannot base it purely off of those audiometric tests. For example, we may see a patient with a mild high frequency hearing loss describe their tinnitus as severe. Or, a person with a self-described mild tinnitus may find it more burdensome, compared to someone else who reports a moderate tinnitus. With different tinnitus scales, their purpose is to uncover patient perceptions of their tinnitus, and find out how it impacts their day-to-day functioning. Then we can determine how best to treat and manage it, as well as how to counsel the individual.

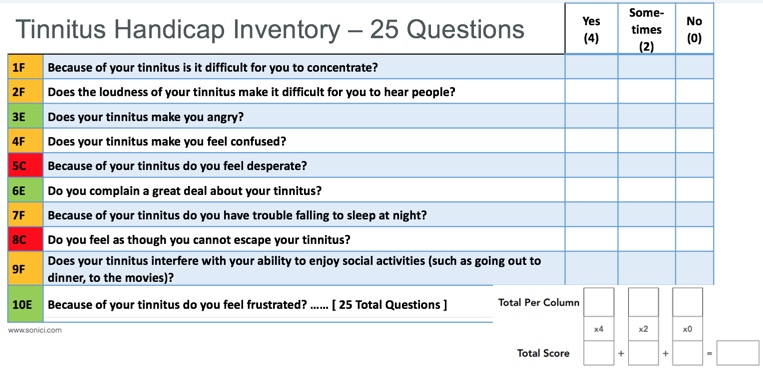

To get an idea of the questions asked on a tinnitus scale, Figure 2 shows the first 10 questions out of 25 total questions on the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI). If the number of the question is followed by an F (shown in orange), it denotes an item on the functional subscale. This subscale is going to help us to determine how well the patient functions during the day with relation to their tinnitus. If a number is followed by an E (shown in green), that denotes an item on an emotional subscale. With this subscale, we are determining how they feel during the day in relation to their tinnitus. If the number is followed by a C (shown in red), this is an item on a catastrophic response scale, to determine if the tinnitus is, perhaps, affecting the patient's mental health. With this inventory, once all the questions are answered, you add up the scores for each column, multiply them by a factor of four, two or zero, and then you get a total score (Newman et al, 1996).

Figure 2. Tinnitus Handicap Inventory sampling of questions.

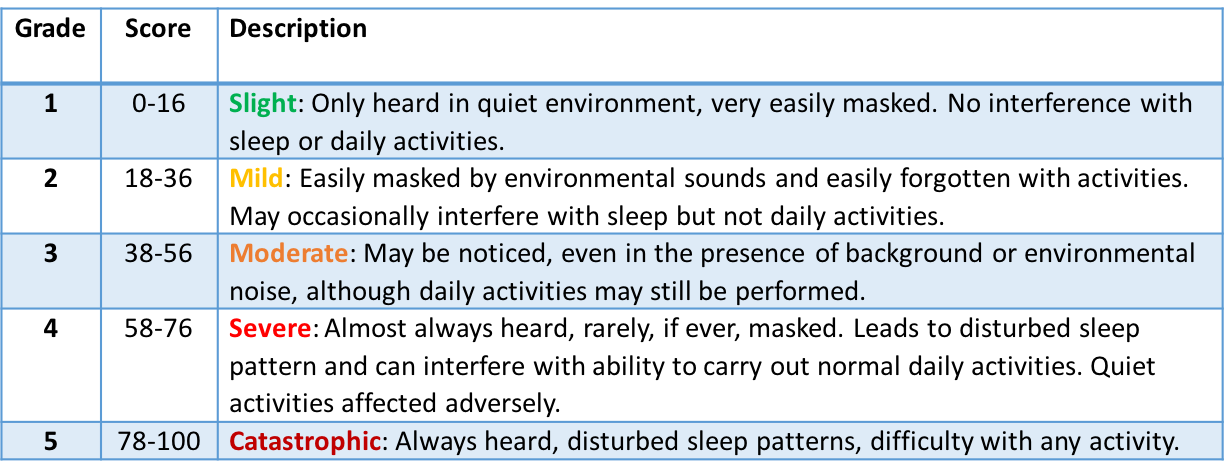

Figure 3 lists the guidelines for grading the severity of tinnitus with the THI scale. A quick glance of the five categories will give an immediate clue as to the health and well-being of the tinnitus patient sitting in front of you. You're definitely going to need a different strategy for someone in category four or five (severe or catastrophic) compared to a patient in category one or two (slight or mild).

Figure 3. THI severity scale.

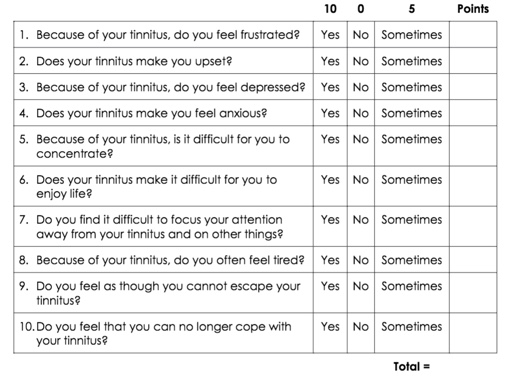

This should give you enough motivation to see that a tinnitus questionnaire is worthwhile to perform on every tinnitus patient. They're easy to do, and perhaps can even be completed while the patient waits in the waiting room before the appointment. The questionnaire can provide a wealth of information before you even start to think about how to formulate your management plan (McCombe et al., 2001). If you're short on time, there's even a screening version of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory, consisting of only 10 questions with much simpler scoring (Figure 4).

Figure 4. THI screening version.

Tinnitus Management vs. Treatment

First, I want to make it clear that the terms "tinnitus treatment" and "tinnitus management" are not interchangeable. We're going to talk about the differences, define these terms, and provide some examples found in each category.

Tinnitus treatment aims to substantially decrease or eliminate the perception of tinnitus. This is achieved through medical, surgical and pharmacological interventions, as well as repetitive magnetic stimulation and neuromodulation. Tinnitus management, on the other hand, aims to improve the way your patient reacts to their tinnitus, through methods such as counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), habituation and tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT), maskers, support groups, stress management and hearing aids/tinnitus instruments.

As we have seen, there are many different causes of tinnitus, and many different treatments for tinnitus. For the purposes of today's webinar, we're only going to focus on the use of hearing aids with tinnitus sound generators as a form of sound therapy. However, it is important to recognize how multi-faceted treatment and management for your tinnitus patient can be. In working with the tinnitus patient, a multidisciplinary team approach is necessary, since one healthcare professional cannot do it all.

Think for a moment about how we use sound during a typical day. We can use music to distract ourselves when we're feeling sad or to relax. We listen to music when we go out socially, or maybe even when working at our desk. We can listen to music with an upbeat tempo to get motivated to exercise. Listening to the radio in the car, whether it be music or a talk show, keeps us company and makes for a better commute. We can also use other noises to distract ourselves, such as the droning sound of a fan when falling asleep. If we want to concentrate, we can also choose to turn off sound or music completely, or to wear earplugs to shut out all sounds, and simply have silence. The point is that there are a variety of ways that we use or do not use sound throughout our day, and we do it almost subconsciously. As we'll find out, the same thing goes for sound therapy with hearing aids, and sound generators within hearing aids.

Management using sound therapy. The American Tinnitus Association refers to sound therapy as "the use of external noise to reduce a patient's reaction to tinnitus". Researcher Marc Fagelson reports that sound therapy can be used in one of three ways to manage tinnitus:

- As a distracting sound, to divert the patient's attention away from their tinnitus.

- As a relaxing sound, to decrease stress or anxiety.

- As a masking sound, to reduce the contrast of the tinnitus in one's listening environment to promote habituation.

Once again, these are often the same ways people without tinnitus use sound in their daily lives. They may want to mask traffic sounds when driving in a car, use sounds to relax after a hard day, or to distract their minds when exercising on a treadmill. As shown in the study that we looked at earlier, different activities in a person's daily life may affect their tinnitus, causing it to improve or worsen. As such, one person may require a few different tinnitus management strategies throughout the course of their day. It's critical to find out how and when a patient's tinnitus changes throughout their day, and to determine whether they want to add more distracting or masking sounds during the day, and perhaps more relaxing sounds in the evening.

Management using hearing aids alone. When fitting a hearing aid to a tinnitus patient, the amplification from the hearing aid in and of itself can provide some masking effects by making ambient noise more audible to the patient. In addition, hearing aids can also assist in distracting a patient from focusing on the tinnitus, by providing other sounds for them to listen to, increasing environmental awareness, and improving their ability to communicate (Vernon and Meikle, 2000). Hearing aids by themselves do provide masking relief for some patients.

Hearing aids with sound generators. Hearing aids with sound generators are another tool that can be used to manage a patient's reaction to their tinnitus. Essentially, these hearing instruments generate a sound that has been proven to either act as a relaxing sound or as a masking sound for the patient. Relaxing sounds include calm sounds that are stable, neutral, rhythmic, and serene. Masking sounds are typically a more broadband or modulated sound, such as white, red or pink sound/noise.

Let's look at the different types of sounds that we can provide for our patients when using tinnitus sound therapy.

- White sound/noise. White noise is the most common sound in tinnitus therapy. White noise is a broadband signal with a flat spectrum and is represented by equal amounts of energy for each given frequency. An example of white noise would include static noise or the /sh/ sound.

- Pink sound/noise. Pink noise is not quite as strong as white noise, but again it's also another broadband signal. However, with pink noise the signal decreases in power by three dB per octave, and may be more tolerable for those patients with a mild to a moderate hearing loss.

- Red sound/noise has yet an even softer sound quality as compared to white or pink. This sound resembles that of a waterfall or the sound of a heavy rainfall. Red noise is also a broadband signal, but it has more energy at lower frequencies than pink noise, and decreases in power by 6 dB per octave.

When looking at tinnitus management and masking sounds that we can provide for the patient, why don't we use just one sound and be done with it? The reason is that a variety of sounds or noises will be beneficial to better address the varying needs of individual patients. Every tinnitus patient that comes into your office may be different. Additionally, even the same tinnitus patient may have different sound requirements throughout their day. For example, we have to consider what works best with their hearing loss configuration. How does that patient's tinnitus change over time? Does a modulated signal work better than an unmodulated or a steadier signal?

Because everyone has different needs, hearing aid manufacturers usually offer a variety of sounds in their tinnitus instruments. We recognize that tinnitus varies, and therefore the sounds that the patient finds beneficial will also vary. For example, Sonic incorporates three nature sounds (Ocean 1, Ocean 2 and Ocean 3) and four different broadband sounds that can be modulated or unmodulated in the Tinnitus SoundSupport programming screen within the EXPRESSfit Pro fitting software. The sound options can also be applied in up to four different programs. Again, it's not a "one and done" approach, where you set it and that's it. There is flexibility in the programming, and also flexibility within the Sonic SoundLink 2 app, where favorites can be created so that your patient can adjust their tinnitus sound support throughout the day. This flexibility is an important factor, because tinnitus is something that the patient may feel that they have absolutely no control over. They may have been told in the past that nothing can be done for their tinnitus. We can provide patients a little bit of power over their tinnitus, allowing them to customize and adjust their settings when they need it.

Case Studies

Case Study 1

Our first case study is a college student who has a mild high frequency sensorineural hearing loss and self-reported mild tinnitus. We targeted three main focus areas of improvement for the patient. She wants to improve her reaction to her tinnitus while she is studying at the library, watching television, and concentrating during weekly exams. In order to achieve this goal, four separate sound therapy programs were set:

- Program one is a general listening program that makes use of the prescribed first target amplification (distracting/amplification alone).

- Program two is set for masking relief during study using modulated pink noise.

- Program three is for watching television (relaxing/nature sound).

- Program four is for concentrating during exams (masking using unmodulated pink noise).

Depending on the patient's feedback, various masking signals were used in an effort to adequately address their individual needs. We did select pink noise because it typically sounds better to those with milder hearing losses, compared to a white noise. We used the modulated versus unmodulated nature sounds, based on the patient's perception during that time and what sounded best for them.

Case Study 2

Next, we have an accountant with a sloping sensorineural hearing loss and moderate tinnitus. For the purposes of selecting the correct settings, we chose three focus areas of improvement. This patient wanted to improve their reaction to their tinnitus while:

- Working at the office

- Reading at night

- Performing a quiet hobby (painting) on the weekends

Again, four separate programs were set:

- Program one is a general listening program which makes use of prescribed amplification to simply provide a distraction for the patient. We are going to amplify external sounds, give them more sound from the environment, perhaps a lot of sounds that were previously missing due to their hearing loss. The amplification alone is going to provide some masking relief.

- Program two was set for masking relief during work (modulated red noise).

- Program three was set specifically for reading at night (relaxing/nature sound).

- Program four is for when they are engaged in their quiet hobby (masking/unmodulated red noise).

Depending upon the patient's feedback, various masking signals were used in an effort to adequately address their needs. Not one single sound modulation is fit for every situation, so we will vary it within the programs. In this example, note that red noise was selected, because this particular patient preferred it over both white and pink noise.

Case Study 3

Our third and final case study involves a computer programmer with severe high frequency sensorineural hearing loss and constant severe tinnitus. This patient desired to focus on improving the reaction to his tinnitus at all times, especially as his stress level changes from morning through the afternoon and then into the evening.

Our computer programmer preferred white noise in all of the sound therapy programs. In this example, the differences in each program truly relate to the modulation rate of the broadband noise.

- In program one, he is going to use an unmodulated or steady masking signal (white noise).

- Switching to program two, he can increase the modulation of the white noise to a moderate, spirited level as he begins his workday, perhaps as his stress levels begin to increase. With spirited modulation, the amplitude of the noise increases and decreases periodically.

- As his day wears on, he can switch to program three to access an even stronger level of modulation (bustling) when his stress levels increase the most.

- Finally, with program four, he drops back down to a mild modulation in the evenings, which is good for trying to wind down at night, perhaps when stress levels are returning back to normal.

Summary and Conclusion

As evidenced throughout the course, there are many factors to consider before setting up a tinnitus management program for a patient. Every case and every patient will be different. It is our responsibility as hearing healthcare professionals to ensure that individual needs are reliably met. Clearly, there are many different ways to treat and to manage the tinnitus, as well as different methods of assessing the tinnitus, in order to ultimately create and finalize a management plan.

If you would like more information on what Sonic has to offer your patients, I invite you to visit our website: www.sonici.com. Tinnitus SoundSupport itself is one of the many new features that's available with the Enchant hearing aids on our latest SoundDNA platform. On our website, you can review our tinnitus SoundSupport web page and then follow the link to our tinnitus SoundSupport technology paper. On the website, we also have a video animation and our Sonic Vimeo video channel as well.

References

Eggermont, J. J. (2012). The neuroscience of tinnitus. Oxford University Press.

Fagelson, M. (2014). Approaches to Tinnitus Management and Treatment. Seminars in hearing, 35(2), 92-104.

Pan, T., Tyler, R. S., Ji, H., Coelho, C., & Gogel, S. A. (2015). Differences among patients that make their tinnitus worse or better. American journal of audiology, 24(4), 469-476.

Perry, B., Gantz, B., & Tyler, R. S. (2000). Tinnitus Handbook.

Shargorodsky, J., Curhan, G. C., & Farwell, W. R. (2010). Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus among US adults. The American journal of medicine, 123(8), 711-718.

Spoendlin, H. (1987). Inner ear pathology and tinnitus. In Proceedings III International Tinnitus Seminar, Muenster, 42-51.

Tyler, R. S. (Ed.). (2000). Tinnitus handbook. San Diego: Singular.

Tyler, R. S., Aran, J. M., & Dauman, R. (1992). Recent advances in tinnitus. American Journal of Audiology, 1(4), 36-44.

Tyler, R. S., & Baker, L. J. (1983). Difficulties experienced by tinnitus sufferers. Journal of Speech and Hearing disorders, 48(2), 150-154

McCombe, A., Baguley, D., Coles, R., McKenna, L., McKinney, C., & Windle‐Taylor, P. (2001). Guidelines for the grading of tinnitus severity: the results of a working group commissioned by the British Association of Otolaryngologists, Head and Neck Surgeons, 1999. Clinical otolaryngology, 26(5), 388-393.

Newman, C. W., Jacobson, G. P., & Spitzer, J. B. (1996). Development of the tinnitus handicap inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 122(2), 143-148.

Vernon, J. A., & Meikle, M. B. (2000). Tinnitus masking. Tinnitus handbook, 313-356.

Citation

Rank, S. (2018, June). Tinnitus tete-a-tete. AudiologyOnline, Article 23316. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com