Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live seminar. Download supplemental course materials here.

Brian Fligor: I am pleased to introduce Frank Wartinger today. Frank is a former 4th year extern in my program at Boston Children’s Hospital and the Musician’s Hearing Program. Frank is now a pediatric audiologist at All Children’s Hospital in Tampa, Florida. He is also a clinical instructor at the University of South Florida. Before completing his Au.D. at Salus University, Frank received his Bachelor’s in Music and Studio Production degree from Purchase Conservatory of Music. He shares his love for audio engineering and music with the musicians and children he serves. Frank plays a variety of musical instruments including the banjo and the melodica.

This is the second presentation in the AudiologyOnline Noise-Induced Hearing Loss webinar series for 2013. You can find my first presentation in the AudiologyOnline course library. Today, Dr. Wartinger will present on Tinnitus Assessment in Young Musicians. The other courses in the series this year are by Dr. Chris Spankovich who will present Food for Thought: Nutrition and Noise, and by Dr. Colleen LePrell who will give a talk called, Otoprotective Agents for Prevention of Acquired Hearing Loss in Humans. With that, I am going to turn this over to Dr. Wartinger.

Frank Wartinger: Thank you, Brian.

As Brian indicated, our topic today is the assessment of tinnitus in young musicians. By young musicians, I'm referring to people who are under 18 years of age and participate in music. Music encompasses a wide range of activities including school bands, marching band, garage bands, school choirs, and music listening. Noise-induced hearing loss and music-induced hearing loss can originate from both music that you play and also music that you listen to and enjoy in your down time. I'm going to be talking about young people generally over the age or 10, as that is the age that we see them begin to engage heavily in music in school, as well as the age we are able to obtain reliable responses to questions about tinnitus.

Why Talk about Youth?

Tinnitus in children is highly under-reported, and with that, it is poorly understood. There are very few research papers describing tinnitus in children, and part of that probably comes from the fact that few children actively complain about tinnitus. Children are at a very high risk for intense and sustained noise exposure with iPods, but we can also talk about school activities, extracurricular activities, inability to wear correct hearing protection or wearing poorly fitting ear plugs and head sets for concerts. There are some very interesting medical-legal issues that we are going to talk about pertaining to minors. There is limited education out there for children. There are some great programs, such as The Dangerous Decibels, but it needs to be more widespread and presented in early education. There are some psychosocial aspects we will be talking about as well as the “invincible youth” syndrome. That is the turn-it-up-until-your-ears-bleed syndrome.

Why Talk about Musicians?

Musicians have their own culture, their own way of life, their own customs, their own lifestyle, and their own language. When you open your clinic to treat musicians, you need to make it musician-friendly, just like you need to make it child-friendly if you are opening up your clinic to children. Musician-friendly means you are not offering them 7:00 am appointments; you offer them 7:00 pm appointments. You are driving to their tour bus. One musician to another, the highest compliment you can receive is that a person has a good ear. It is very similar to a chef having a good palate or a quarterback having a good arm. Having a good ear means that you can hear and listen well. You can recognize fine detail, and you have great acuity of your ears. There is so much emphasis on this ability to have a good ear that having a bad ear would end someone’s career, or at least that is the thinking is behind many people’s fear of approaching audiology, especially musicians. “If someone finds out that my hearing is not good or I have this ringing in my ear, no one will want me to mix their next album.”

Obviously musicians run a very high risk for noise exposure, and they work in an unregulated industry. This does not mean that we want NIOSH going to every single concert and telling everyone who works and attends that they need to adhere to NIOSH standards. However, we do need a lot more education. Music enjoyment does not have to be reckless. It can be responsible, but unregulated.

Before we launch into tinnitus, I want to mention that what we are talking about is not widely perceived as “cool.” As adults, our ability to understand what is “cool” or “hip” is very limited. If you Google cool ear plugs, you will find all kinds of things, some which have nothing to do with ear plugs. My favorite image was of a dangling earring with a foam earplug attached to the bottom, so the earplug would always be ready on the earring. They are patent pending, come to find out.

Why Do I Care about Tinnitus in Young Musicians?

I come at this question from different perspectives. First, as an audiologist, our role is to evaluate and to treat the patient. Tinnitus is part of the patient; so we are treating that person for everything that is affected by the tinnitus as well, whether it is their emotional state or their listening ability. The second part of being an audiologist for people with noise exposure is hearing conservation. From an audiologist’s perspective, hearing conservation means that we want to protect the hearing that is there, limit further damage, and mitigate the problems before they get worse.

From a musician’s standpoint, hearing conservation means something completed different. They may say things such as, “I want to keep my good ear as a musician. Ear training is something I have to do. Exposing myself to music every day is something I have to do. How do I keep my good hearing? Does that mean I should wear ear plugs when I mow the lawn so I can play drums for an hour without ear plugs?” This is different for everyone. We have to go step by step.

I also want to introduce a concept that I take very seriously, which is music conservation, not hearing conservation. Whenever I see a child who says they play the guitar, I want that child to not stop playing the guitar because of hearing. I want that child to go on and play the guitar and write music, and enjoy music throughout their entire life. That is music conservation. If that person’s hearing or tinnitus gets in the way of their ability to play music and to make music or have a professional career with music, we are losing music in the world, and that is a sad thing. Music conservation also applies to professionals. We want them to continue doing the wonderful work that they do.

I also come at it this topic from a third perspective, which is that I, personally, have tinnitus. My tinnitus has been with me since my early teens. I want to help us care for these patients with tinnitus. I have a lot of empathy for the patients I see with tinnitus. I feel like my approach with a tinnitus patient might be a little bit different had I not experiences tinnitus and had an appreciation of what they are going through. We also need to educate the music community about what tinnitus is, what tinnitus is not, and what can be done to prevent ever having this kind of a concern.

Case Study

I am going to start with a case study. Spoiler Alert! I am talking about myself here. A 14-year-old male comes into your clinic presenting with tinnitus. They describe a temporary tinnitus following noise exposure for about the last year or so. At present, it is a constant high-pitch ringing and also a hissing. It gets worse whenever they are in their rock band practice, whenever they play shows, or during any kind of musical activity, including playing piano quietly in the house. It is starting to interfere with their regular sleep schedule. This is the reason why this patient contacted you in the first place. This is the reason why this 14-year-old boy went to their parents and said, “Mom and Dad, I need to go to the doctor because I have a problem.” That is a powerful thing for any teenager to admit. Once sleep becomes affected by an ailment, it is usually a clinical issue and something that needs to be addressed immediately. Sleep for a child does not only affect the child; it affects the whole house. This patient is concerned that he is losing his hearing completely. He currently does recording at home and wants nothing more than to pursue a career in music. If he loses his hearing, there is no more dream of a music career.

At his first audiology visit, a hearing test is performed that reveals hearing within normal limits. The audiologist recommends musician’s ear plugs. He takes ear impressions and if says if there are any problems with the impressions, he should come back to the clinic. Other than that, he will mail the ear plugs to the patient’s home. I do not mean to be judgmental of this initial visit, because this initial visit obviously directed me to where I am now, which is audiology. However, I do need to point out a few things for constructive criticism.

First, there was no questionnaire, no discussion, and no conversation regarding the distress. This is a chronic problem related to music and exposure, and it is affecting sleep. There are some serious concerns here about losing hearing. That was not discussed. If it was discussed, it was while the impression material was in my ears. Perhaps it was discussed with my parents. When you are working with a patient, do not try to discuss something while the impression material is in their ears. You will not be able to get a whole lot done that way.

The second point is the term “within normal limits” is something some audiologists say quite often referring to hearing or other measurements. Within normal limits sounds like you are saying “average” or “okay.” Within normal limits or average hearing is not a sufficient type of hearing for a person who is planning on becoming a musician for their career. This kind of person wants their ears to be pristine; they do not want average ears. It would be like telling someone who wants to be a track star that their running is within normal limits and they are doing an average job.

To give you a little perspective on this, at this point I am 14 years old doing recording on a four-track tape deck, bouncing tracks between each other to multi-track. When the audiologist tested my hearing, he said, “Your hearing is fine between this point and this point, which is between 250 and 8000 Hz. It is all within plus and minus 15 dB from 0”. That is about half of the sound range that this 14-year-old knows in Hz. This 14-year-old is used to listening to 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz, and to tell him that about half of the range is within 15 dB of normal is not really enough to be a professional musician. That is a huge amount to be up or down in the recording in the music standpoint. If you raise 3000 Hz up by 3 or 4 dB on the guitar, you go from sounding like you have a Stratocaster to sounding like you have a Telecaster. That is an important difference for a musician. It is not appreciated by most audiologists, especially when we describe threshold responses to a patient.

Music conservation does not start with an ear plug in the ear, especially if you are a musician. There are so many things that you can do before that. If you are going to be fitting a musician with ear plugs, I recommend that you do not mail the ear plugs home. You should be doing some kind of fitting and verification of those attenuators to make sure that they are as flat or acceptable as possible.

It is important to understand that a young child is not a small adult. Although a child or young adult may not have the words to describe what they want to say, they do understand what you are saying to their parents. They want to be involved in that decision-making process.

Tinnitus

Tinnitus is a perceived sound not attributed to an external stimuli. It has been described as a phantom auditory perception (Jasterboff, 1990), which I think is a fantastic term. It relates tinnitus to phantom limb syndrome and also to chronic pain, which are very useful concepts. Tinnitus is a common symptom, but it is rarely clinically significant. Almost everyone in the world has experienced tinnitus or constant noise in their ears at some point, but only a small fraction of Americans, approximately 20 million, are bothered by this. This is small compared to the whole population. Tinnitus is in the brain, not in the ear, even if it started in the ear.

Noise exposure is by far the most common cause of tinnitus. The most common type of tinnitus is transient, spontaneous tinnitus, also known as pings. This is where a high-pitched ringing will come into usually just one ear, and the hearing acuity is dampened in that ear at the same time. This lasts for about 5 to 30 seconds. If you describe that to most people, they will tell you that they have experienced this at one time or another. Most people experience it several times a week. This does not mean anything and is completely normal.

Temporary tinnitus following a temporary threshold shift is very common, especially with noise, concerts, and music. I have a sound clip that includes sound simulations of the most common types of tinnitus.

Here is what you will hear on this clip:

- Ringing. The first sound is one that many people describe as ringing. This is about a 9 kHz tone. If someone describes their tinnitus as a hissing sound, they may be experiencing something similar to this.

- Buzzing. Next, you will hear tinnitus that might be described as a buzzing sound. I believe most people who use the term "buzzing" to describe their tinnitus are referring to multi-tonal ringing with some kind of noise element mixed.

- Noise with multiple pitches. The third sound includes multiple pitches in the noise. If you had to do tinnitus pitch matching, the listener would probably select the highest pitch, but you can hear how it would be very difficult to find a pitch match on a sound containing with so many different elements.

- My tinnitus. The fourth and last sound in this clip is my own tinnitus. It has multiple ringing tones, with different pitches in both ears. It is very high pitched, but with low-pitch rumbles and hisses involved. You can download this sample at https://tinyurl.com/FW-My-Tinnitus. Feel free to use it for your personal use.

The closest I can get when pitch-matching my tinnitus would be about 8000 Hz narrow-band noise right around 10 dB SL. To me, however, it sounds like a freight train. Interestingly, I have almost normal otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) in my right ear, and in my left ear they drop down around 8000 Hz.

While we will not be discussing medically significant tinnitus today, I do want to briefly mention it. If you have a patient with unilateral, pulsatile or low-pitched tinnitus, they should be referred to an ENT or otologist to rule out an underlying medical condition.

Tinnitus Effects

Tinnitus can have major effects on a patient. The biggest one is emotional distress. That is when tinnitus is perceived as a threat to your health, career, or quality of life (Hallam, Jakes, & Hinchcliffe, 1988). It can have effects on your cognition, reduced capacity for voluntary conscious effortful and strategic control (Rossiter, Stevens, & Walker, 2006). It can impair selective and divided attention (Stevens, Walker, Boyer, & Gallagher, 2007), which is extremely important when we are talking about children who are in school. Sleep disturbances can either be a direct response to perception of tinnitus or completely unrelated stress-induced insomnia (Ramkumar & Rangasayee, 2010). Stress-induced insomnia, from some kind of extra stress in your life, may also exacerbate tinnitus. That needs to be explored when you discuss it with a child.

Other music-induced hearing disorders include hyperacusis and misophonia. Hyperacusis pertains to loud or specific-pitched sounds. It is a sensitivity of your ear to physical characteristics of the sound. Misophonia is a sensitivity of your brain to emotional or experiential or contextual issues within the sound, such as, “When that person chews gum, I am ready to go through the roof”. This is commonly concurrent with tinnitus. Exacerbation of tinnitus is a very common reason given when people say that they avoid loud sounds or specific sounds (Jastreboff & Jastreboff, 2002). This can have a huge impact on a musician’s life. For instance, if a guitar player told you that they cannot not stand the sound of their drummer’s ride cymbal, they will stop playing with that drummer.

Another music-induced hearing disorder is called aural distortions. This can be described as an artifact, or an extra distortion of intensity growth. As sounds get louder, they do not grow in an expected and linear way like they used to. It is also called frequency splatter. Aural distortions are typically heard with high inputs and are often unilateral. They probably stem from some kind of over-exposure in the past. These distortions are commonly reported by musician, particularly by mixing engineers who are very in-tune with how each of their ears hears. It may motivate musicians to play with softer situations, switching to an acoustic set-up from their old, loud rock band, or mixing at a quieter level. For a child, this might be relative to saying, “I really do not like playing in wind ensemble anymore, because I sit right in front of the trumpets and that is not fun. I would much rather play chamber music. I would much rather join the choir or maybe drop out of band entirely and do art.” Again, we are talking about music conservation. I do not want that person to drop out of band because of their ears.

Tinnitus in Children

The prevalence of tinnitus increases with age. And while some data exists about tinnitus in young adults, there is very little data published about younger children and teens. There is more research to be done in this area. I believe it is much more common than what we are seeing reported.

Here is some startling data. Ninety-seven percent of all third-graders in a self-report said that they had some hazardous noise exposure (Blair, Hardegree, & Benson, 1996). Almost all young people in another study (Gilles, De Ridder, Van Hal, Wouters, Klein Punte, et al., 2012) reported tinnitus after loud music exposure, even without other audiologic complaints such as dampening of hearing or pressure in the ears. About four out of five children with tinnitus report sleep difficulties (Kentish, Crocker, & McKenna, 2000). That is probably one of the most commonly reported concerns with tinnitus and children. About 17% of teenagers aged 13 to 19 have some kind of noise sensitivity (Widén & Erlandsson, 2004). About the same number also have a noise-induced threshold shift (Henderson, Testa, & Hartnick, 2011), and the same amount listen to music players at levels exceeding NIOSH standards (Martin, 2008). These studies were all done at different times, so I know that they were not the same teenagers, but it is still interesting how close those numbers are. About 9% of teenagers have some kind of permanent tinnitus (Widén & Erlandsson 2004), and about 10% of those children are bothered by it to the point where they need to address it and talk through it in your clinic.

The prevalence numbers for tinnitus in normal hearing and hearing-impaired children vary greatly, depending on the study. We need to narrow the prevalence down and define clinically significant tinnitus in these cases. Are we asking, “Have you ever heard a noise?” or is it, “Are you bothered by the ringing sounds in your ears?” A prevalence of 6% to 55% is for normal children and 25% to 66% in hearing-impaired children are wide ranges (Nodar & Lezak, 1984; Graham & Butler, 1984; Baguley & McFerran, 1999).

Common concerns for parents is that the tinnitus perception described by their children is a sign of hearing loss, worsening of an established hearing loss or a sign that there is some mental health or catastrophic health concerns. Children do complain less about ailments, and they are much more tolerant. Adults are less so. If we get an ear infection as an adult, we stay home. We complain and eat chicken soup all day. Children with chronic health concerns do not complain about it the way that adults do.

I question how it is that children are reporting less tinnitus than adults. If a child has tinnitus, I would imagine that their cognitive habituation abilities are reduced compared to that of an adult, because they are not able to rationally do biofeedback and understand what it is that they are hearing in order to get rid of it. However, I have wondered if that is offset by neuroplasticity changes and their natural coping methods, whether that is playing, taking an extra teddy bear to bed at night, et cetera.

Assessment

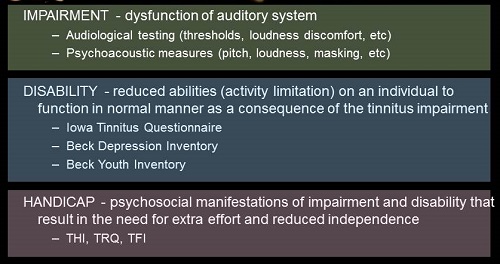

When we assess tinnitus in the clinic, we can look at three different parts of the person: impairment, disability, and handicap (Figure 1). As audiologists, we usually focus on the impairment and sometimes look at handicap. Rarely do we look at the disability. The impairment in this case is the dysfunction of the auditory system. We can do booth testing to find this out. The disability is the reduced ability or activity limitations because of that impairment. For this, we need to look at depression inventories, such as the Beck Youth Inventory, which is an adaptation of the Beck Depression Inventory, and is much more appropriate for children. This reaches a bit outside of our scope and our comfort zone.

Figure 1. Assessment of tinnitus into impairment, disability and handicap.

Back within our scope is handicap, which is the psychosocial manifestations of impairment and disability that result in the need for extra effort and reduced independence. Clinical audiologists are very used to talking with hearing-impaired patients about the handicap of their hearing loss. Tinnitus patients are no different.

The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI; Newman, Jacobson, & Spitzer, 1996), the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ; Wilson, Henry, Bowen, & Haralambous,1991), and the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI) are three tools that I am going to be talking about today. With a little searching, you can find about 30 tinnitus questionnaires out there in English, most of which are likely not used on a global scale. These are just the three that I have seen and used most often in relation to children.

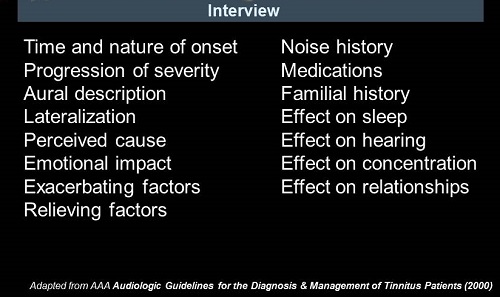

Every patient interaction starts with an interview. We need to know a lot of things about this person’s tinnitus (Figure 2). Even with adults, this is a tough conversation to have because people do not want to talk about the thing that has been bothering them for all this time. Getting down to the bottom of it means that they have to think about and focus on the thing that they are trying to avoid.

Figure 2. Tinnitus interview topics.

When asking these questions to children (Figure 2), we need to word them completely differently and avoid putting thoughts of negativity into the child’s mind before the answer is given. Steer away from simple yes/no questions that could lead to a circular pattern of answering, such as saying no to everything. Some wordings for children that seem to work well with tinnitus are “Do you ever hear noises or sounds in your ears?” Notice that there is nothing negative in that statement. “What do you call them?” I am not giving them any terminology. I am not asking if they hear ringing, buzzing, hissing, or car alarms in their ear. I want them to tell me what they call them. “What makes them go away?” “What makes them get better?” I am trying to avoid the word worse. “What do you do when you hear them?” I am trying to get to the bottom of what their natural coping strategy might be. “How do the sounds make you feel?” Asking a child how do they feel is a very powerful question. The answer may not come back to you in full sentences. It may come back to you with facial expressions and with reading the parents as well.

For younger children, I ask them to draw a picture of their tinnitus. “What does it look like?” “Is it a big brown monster sitting on top of your house? Or is it this little squiggly noodle that you keep in your pocket?” “Can you tell me how you perceive this?” We are not just dealing with the child; we are dealing with the family. You have to identify the parental worries as well as the child’s. “How is the tinnitus affecting your life at home? How is this tinnitus affecting school work? How is this tinnitus affecting your ability to sleep and the child’s ability to keep you from waking up too early in the morning?”

We then start with a hearing test. For an adult, we do a comprehensive audio, including QuickSIN, loudness discomfort levels (LDLs) and most comfortable loudness levels (MCLs). All of those measures may be more difficult for children, depending on the age. In most cases, a developmentally-appropriate child at 5 years of age is considered an adult from an audiologic testing perception. They are going to raise their hand or tell you when they heard a sound with good accuracy. That said, the QuickSIN may be difficult, even for an early teenager or pre-teen. You may try the BKB-SIN instead, as it uses a lower language level and has norms for children down to age five. LDLs are going to be extremely difficult to get, and you need to have some kind of rapport with a child in order for them to let you approach 100 dB or higher in their ears. Otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) are a great help for the tinnitus patient, because they are a visual representation of auditory impairment even when the audiogram comes back completely normal. This allows you the ability to say, “Look on this graph. This is a problem that may not go away or get worse. We need to address this now. We need to start using some hearing protection and mitigating the sounds that you are hearing in your life.”

Psychoacoustic measures such as pitch matching, loudness matching, minimal masking levels, and residual inhibition, are difficult to perform on adults, much less, children. Treat this like you would do an auditory processing disorder evaluation. Provide several breaks, give lots of reinforcement, and accept that there is some amount of validity question when you are doing this kind of testing with a child.

Questionnaires

I want to talk about the questionnaires that I chose. The TRQ was described as a screening instrument that distinguishes tinnitus sufferers who cope with the problem from those who do not cope well. The second part is something that you will see with all questionnaires. It is a measure of psychological distress before and after treatment. These questionnaires are designed to help show improvement or lack of improvement with certain therapies. There are 26 questions, and it comes in a five-point Likert scale. It is very easy to answer.

I want to point out a couple of things about the TRQ. The first five statements, to which the patient must agree or disagree, are, “My tinnitus has made me unhappy, feel tense, feel irritable, feel angry, cry.” What you are essentially saying is that your tinnitus has made you a normal teenager who is unhappy, tense, irritable, angry, and crying. I do not mean to make fun of teenagers here, but that describes most of the teenagers that you have ever met. Number 18 says, “My tinnitus interfered with my ability to work.” Ability to work means something different to a child than an adult. When we ask a question, the context or the person’s perceptual basis changes what that question means. This question is one I worry about because what you are loading the question by asking, “Is the tinnitus or ringing the reason you are not doing well in school?” “Oh yeah. That is the reason why I cannot pass any of my classes!” I do not want to go back to being a teenager, and I do not want to belittle the teenager, but giving a child an out like that can be a very sensitive subject.

Number 24 of the TRQ says, “My tinnitus has led me to think about suicide.” When we ask this question, whether you are asking an adult or a child, you need to have an appropriate referrals ready. If that person says, “Yes, this makes me think of suicide,” who are we going to call next? Legally, what is our next action? We want to protect that person’s life and we want to make sure that this does not go too far. What is the next game plan?

The legal implications of this answer for a minor are actually a little confusing to me. I had to discuss this with our legal department and the psychologists within All Children’s Hospital. If a teenager answers this question as a 0, or “never,” then great. While they do not think about suicide at the moment, I have just introduced this concept to them. If a person comes in and says 4, that means they think about suicide almost all of the time. We need to walk that person down to the emergency room and put them on watch. We need to have a psychologist come down immediately and tell their parents what is going on. What happens if they say, “My tinnitus has led me to think about suicide a little of the time.” This is a gray area. The legal department told me that the next step would be social services and a psychology evaluation. If you are concerned about the person’s plans to injure themselves, injure someone else, or if they are worried of harm to themselves, we need to discuss this with law enforcement immediately.

As a minor, a person under 18 does not have rights to medical record privacy. Their parents have rights to access medical records. As a clinician, we can keep information from the parents if we feel like it is going to help. We can develop great rapport with a 16-year-old behind closed doors with the parent out in the waiting room. They may tell you all kinds of information that they are not going to tell their parents about their noise exposure, or what they are doing as far as listening to excessive noise. However, once they talk about suicide or injuring someone else, we need to let that person know that we have to tell their caregiver this information. You do not want to break rapport or trust with them, but the legal line has been crossed. Again, I am worried about the power of suggestion and the negative ideations that we are causing simply by asking the question.

The next one is the THI. It is a self-report tinnitus handicap measure that can be used in a busy clinical practice to quantify the impact of tinnitus on daily living. There are three subcategories: functional, emotional, and catastrophic. Number 11 on the THI says, “Because of your tinnitus, do you feel you have a terrible disease?” This is a negative ideation that we are talking about. This is part of the catastrophic index. Number 13 says, “Does your tinnitus interfere with your job or household duties?” Let’s say we hand this to a 12-year-old. What is their job? What are their household duties? Their household duties are their chores. Does tinnitus interfere with their ability to do their chores? “Yes, that is why I have not gotten my room clean for the last three months!” You are giving the child a bit of an out there. You have to worry about the answer that comes out of this. Number 15 says, “Because of your tinnitus, is it difficult for you to read?” That 12-year-old may say, “Yes, I am doing terrible in reading, and it is because of my tinnitus. Now can I go home?”

The last one is the TFI. In this questionnaire, they removed all of the catastrophic subscale questions of suicide, despair, and terrible distress. By taking out the negative ideations, you are not putting negativity into the patient before treatment and evaluation. There are 25 questions and 8 subcategories. Every question has a different scale. It is difficult to take as there is a lot of reading, looking, and circling. When I took it, I switched a couple of numbers back and forth by mistake. It is a bit complicated.

The second point I want to make known, again, is that this describes most teenagers. Tinnitus limits your ability to concentrate, to think clearly, and to focus your attention. This described me most days as well. We need to be careful about giving that out to children.

The TFI looks a bit like an SAT test. We are handing this paper over to someone saying, “I need your honest opinion and thoughts to this. There are no right or wrong answers. Here are the instructions. Please read each question below carefully. To answer a question, select one of the numbers that is listed to that question and draw a circle around it like this, and also bubble in your answer sheet completely with your #2 pencil.” I worry that we are promoting this as a quiz or a test and that they are being graded. Number 22 asks, “Does tinnitus cause you difficulty performing your work, home maintenance, school work, or caring for children?” Obviously work means a different thing to a teenager. When you hand this to a child, caring for children means being nice to your friends or holding a baby correctly.

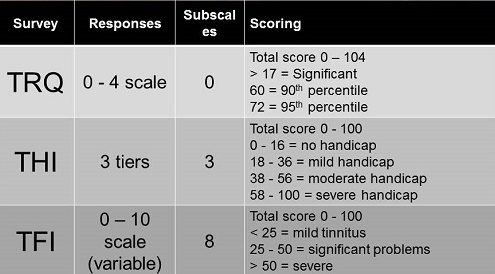

I wanted to summarize all of the tinnitus questionnaires so that you have them for future reference (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Summary of tinnitus questionnaires (TRQ, THI, and TFI) including responses, subscales and scoring.

There are no child or youth-specific questionnaires that have been developed for tinnitus. That said, there are also no musician-specific questionnaires that have been developed for tinnitus. We are dealing with two sub-populations with very specific needs and a very specific perspective on what their ears are and how they work. Normative data may not translate to children or to musicians, for that matter. It is not clear if they have the same needs and the same difference in scores required to demonstrate tinnitus or show a significant improvement. Perhaps for a musician, a significant score on the TRQ is much lower than a significant score for a non-musician. For a child, it may be much higher. I do not know. Due to that, are these valid pre- and post-treatment measures of outcome? I am not sure of that either. A test-taking mentality should not be used. “This is not a quiz. You will not be graded as there are no right or wrong answers.” Even when explaining that, you must take everything with a grain of salt. The answers could be widely variable.

Gilles et al. (2012) put out the Youth Attitude towards Noise Scale (YANS). I thought this was very useful. This was presented directly to university students, and it asked questions about their attitude towards noise, the influence of peers, their ability to manipulate hearing protection, and how those factors played into their use of hearing protection.

As stated previously, when presenting questionnaires to any youth, negative affect is something you have to watch for. This is that child who comes in and when you ask them how their day was at school, they say, “Boring”, or when you ask them how their dinner was, they say, “It sucked.” Everything is a negative, low, one-word answer. This kind of an affect is going to influence the results on all self-reported measures across the board. The way to find out if this person with a score of 100 on the THI has the most severe tinnitus possible in the world or just a negative affect is to give them some more pure measures of negative affect, such as the depression or the youth inventory. That might help explain those outlier tinnitus scores. Either way, when you see high tinnitus scores, whether it is a psychological issue or truly severe tinnitus, you probably should refer that individual to a psychologist.

Allure of disaster is a concept that I want to touch on. This is common with teenagers, and it is the feeling like they want something exciting to happen, even it is bad. They want to be that kid with a cool disease, because, “Maybe, then people would like me.” It is a longing for tragedy. This pertains to heroism and risk taking, which are prevalent in teenagers. The allure of disaster can also promote what I like to call “exaggeration of a hearing problem” or what we would also like to refer to as malingering. If a person comes in saying, “I have this problem and it is causing amazing amounts of discomfort for me, and I need to leave school and have special adaptations to my life because of it,” we have to be cautious of malingering or exaggeration. There is also just the teenager attitude, that “life sucks, school sucks, and I’m bored.”

Conclusions

If I had to give a blue ribbon to one of the tinnitus questionnaires, I would give it to the TFI. It is the most appropriate for children with its questions, in my opinion. Removing the catastrophic questions helps a lot with that, but it is also the most complicated form. Consider going off the form and verbally asking the questions. It may not be useful as a normative calibrated outcome measurement because it was not normed on children. Go off the form and use this as a guided interview.

If using the questionnaires with the catastrophic questions, such as suicide, depression, and despair, be ready with your referrals and know your legal action plan within your facility, department, or clinic, and state that before you get started. That goes for adults as well.

Children are not smaller adults. You are treating a patient who happens to be younger along with a family. You are treating the parents, the friends, the siblings, and extended relatives. Everyone is affected by this.

Hearing conservation for musicians is what we as audiologists should focus on. That starts with education, not with ear plugs. Start with information about the person’s ears and how to protect them. We need to meet the musicians half way and respect their culture. Yes, they may come in unkempt and sleepy, but we need to respect their culture and make our clinic appropriate for them, just like we make our pediatric clinics appropriate for children.

Music conservation for audiologists is the second side of that. Save the musician and save the music is my take-home message. When you work with a patient who says they are a professional musician or they would like to be a professional musician, but their ears are ringing whenever they play guitar, I hope you would be to look at that patient as a whole and say that this person’s livelihood and enjoyment in life stems from their ability to make music. Not only that, the world benefits when this person makes music. If this person stops making music because we cannot help them get the right kind of ear plug and fit that allows them to sing using their in-ear monitors or get relief from their tinnitus, then we lose the future music that person could make. I urge all of you who are working with musicians, teenagers or younger children who are interested in music to try to save the music that that person will make by helping to save that person’s ears. Educate them on how to protect their ears in the future.

Questions and Answers

In regard to teenagers with tinnitus, do you feel that teenagers or children have lower threshold are not being sent them for an MRI with gadolinium enhancement or other things such as blood work? Are they going to be given a fast and furious, shotgun work-up approach?

Twenty percent of adults are bothered by their tinnitus; only half-a-percent of children are bothered by their tinnitus, right? Why is this an issue? They mentioned tinnitus, but they are just a kid. Many practitioners in the medical field approach the complaint as something not to worry about because they are children. It is probably nothing. I completely agree that children get fast work-ups.

Brian Fligor: I think we are more afraid of missing things like tumors or Lyme disease or other auto-immune diseases in a young child or teenager. It makes me think that the work-up with a teenager might be a little more invasive out of the medicolegal fears that the ENT or audiologist might have. Making them go through this whole process might be invasive and a little bit uncomfortable, and in fact, it could make their reaction to the tinnitus even worse. Do you have any comments about that?

Frank Wartinger: I agree. I think we need to focus on the patient, and the tinnitus reaction is almost more important than the symptom itself. Since most people have some degree of tinnitus and ignore it or able to distance their limbic system from the effects, we can gloss over that fairly easily and forget that tinnitus is a physical manifestation that affects the person emotionally.

Are musicians' flat plugs not good for a child?

I think they are great for a child. However, they can be more difficult to make due to a child’s smaller ear canal. Just as with earmolds for children’s hearing aids, these also have to be remade quite often. We are aware that children lose them more often than older patients. These things present some additional challenges. I also would not make them with vinyl. I do not see any problem with fitting them for a child as long as you are aware of these factors.. I think they are great.

When can you ever be alone with a 16-year-old or any pediatric patient? Don’t parents always have to be present?

Good question. My general rule of thumb is to take the parent back with you so that you avoid any kinds of issue later on. You never know what the child is going to say or what the parent is going to say. That said, you may try to test a 10-year-old in the booth, and that 10-year-old wants mom to sit outside and be in the booth by himself to show that he can do this. There is no legal problem with being in the room with the door closed with a child. You need to be upfront about what is going on beforehand. If you feel like the situation is uncomfortable for any reason, open the door. The reason that I even mentioned that with tinnitus is that when you are talking to a child about something so emotionally distressing as tinnitus, oftentimes they do not want to talk about it with their parents. You might be that stranger that they can finally open up with and explain all the problems they have. You can be there for them. Psychologists do this all the time. They say to the child that it is a closed-door session and whatever they tell them stays with them and does not go to the parent unless they say one of three things, which are that they are planning on injuring themselves, planning on injuring someone else, or someone else is harming them. I hope that does answer the question.

Brian Fligor: The only thing I would add, given my experience at a children’s hospital, is that when in doubt, always have the parent around. If there are any questions about your own hospital’s policy, you should ask your division chief, check with general counsel, and when in doubt, err on the side of caution. Frank’s points are spot on. Some of these conversations are ones where you cannot be helpful if the environment does not allow you to be. Sometimes the parent is the one who is exacerbating the issue, and separating that parent from that situation will be about the only way you can help your patient. Talk to psychologists about how best to manage this and to structure a session that is appropriate, as they are the ones who have had to regularly deal with confidentiality in teenagers.

Would you suggest ultra-high frequency testing as well as ultra-low to make the hearing test more musician-friendly?

I would love it if our hearing tests went from 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz in 1-dB steps. Is that clinically appropriate? Do we have norms for what hearing is supposed to be out past 8000 Hz and what hearing is supposed to be below 125 Hz? That is a tricky point to get into. This might be a similar situation to the person who is distressed by learning that their hearing is only “within normal limits.” Owning up to the limitations of the audio, I think, would provoke the same reaction. Some patients may want to have a broad-spectrum hearing test, but perhaps not mentioning the limitations of what could be possible will save these patients more frustration and worry.

References

Baguley, D. M., & McFerran, D. J. (1999). Tinnitus in childhood. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 49(2), 99-105.

Blair, J. C, Hardegree, D., & Benson, P. V. (1996). Necessity and effectiveness of a hearing conservation program for elementary students. Journal of Educational Audiology, 4, 12-16.

Gilles, A., De Ridder, D., Van Hal, G., Wouters, K., Klein Punte, A., & Van de Heyning, P. (2012). Prevalence of leisure noise-induced tinnitus and the attitude toward noise in university students. Otology & Neurotology, 33(6), 899-906. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31825d640a.

Graham, J. M., & Butler, J. (1984). Tinnitus in children. The Journal of Laryngology and Otology, 9(Suppl.), 236-241.

Hallam, R. S., Jakes, S. C., & Hinchcliffe, R. (1988). Cognitive variables in tinnitus annoyance. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(Pt 3), 213-222.

Henderson, E., Testa, M. A., & Hartnick, C. (2011). Prevalence of noise-induced hearing-threshold shifts and hearing loss among US youths. Pediatrics, 127(1), e39-46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0926.

Jastreboff, M. M., & Jastreboff, P. J. (2002). Decreased sound tolerance and Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT). Australian and New Zealand Journal of Audiology, 24(2), 74-84.

Kentish, R., Crocker, S., & McKenna, L. (2000). Children's experience of tinnitus: A preliminary survey of children presenting to a psychology department. British Journal of Audiology, 34(6), 335–340.

Martin, W. H. (2008). Dangerous Decibels®. Partnership for preventing noise induced hearing loss and tinnitus in children. Seminars in Hearing, 29, 102-110.

Meikle, M. B., Henry, J. A., Griest, S. E., Stewart, B. J., Abrams, H. B., et al. (2012). The tinnitus functional index: development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear and Hearing, 33(2), 153-176. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822f67c0.

Newman, C. W., Jacobson, G. P., & Spitzer, J. B. (1996). Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, 122(2), 143-148.

Nodar, R. H., & Lezak, M. H. W. (1984). Pediatric tinnitus: A thesis revised. The Journal of Laryngology and Otology, 98, 234-235.

Ramkumar, V., & Rangasayee, R. (2010). Studying tinnitus in the ICF framework. International Journal of Audiology, 49(9), 645-650. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2010.484828.

Rossiter, S., Stevens, C., & Walker, G. (2006). Tinnitus and its effects on working memory and attention. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49(1), 150-160.

Stevens, C., Walker, G., Boyer, M., & Gallagher, M. (2007). Severe tinnitus and its effect on selective and divided attention. International Journal of Audiology, 46(5), 208-216.

Widén, S. E., & Erlandsson, S. I. (2004). Self-reported tinnitus and noise sensitivity among adolescents in Sweden. Noise & Health, 7(25), 29-40.

Wilson, P. H., Henry, J., Bowen, M., Haralambous, G. (1991). Tinnitus reaction questionnaire: psychometric properties of a measure of distress associated with tinnitus. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 34(1), 197-201.

Cite this content as:

Wartinger, F. (2014, February). Tinnitus assessment in young musicians. AudiologyOnline, Article 12498. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com