Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Therapeutic Techniques to Build Alliance with Complex Patients and Their Families.

Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Present specific strategies for improving communication with patients.

- Discuss the potential impact of multicultural factors on the patient and provider experience.

- Review specific case examples to highlight these techniques.

Introduction

I am very excited to discuss therapeutic strategies to build an alliance with complex patients and their families. This is an issue that I find vital to our profession and is one that is near and dear to me. We will discuss different techniques and strategies that I have been trying to use and figure out how we might be able to apply them in your context. We will talk about general skills that can be used for any patient that comes into your office. Then we will cover the importance of considering diversity within healthcare, as it ties into thinking about the entire person and their family and engaging patients in behavior change. When we are talking about working with complex families, we are discussing this idea of behavior change. How do I get this family or patient to engage in a different pattern of behavior than they are currently doing? Then we will have some role-play or case examples to try and bring it to life. I want this course to feel concrete and applicable.

My Background

I completed my Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology at the University of Miami. My specialization is in Pediatric Psychology. The vast majority of my training has been done in a hospital setting with pediatric patients. Not only specific to hearing loss, but other things such as in-patient consultations, cranial facial patients, cardiac admissions, diabetes, cancer, pretty much any pediatric medical illness. After that, I did my residency and fellowship at Nemours/AI duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Delaware. During that time, I started to emphasize a focus on working with children who were deaf and hard of hearing within our audiology ENT clinics and the cleft palate cranial facial clinic. Currently, I am still in that role at Nemours. My specialization is cranial facial cleft palate, audiology, ENT, and working on integrating psychology services into our clinics for all of our families.

I also am a person with a hearing loss. I was born with severe to profound hearing loss, Connexin 26. I was diagnosed at four months of age and was bilaterally aided at five months of age. I wore hearing aids for the majority of my life and was implanted on my right side at 28. I share that information because, in creating this presentation, I'm not only drawing on my professional experience and training but also over 30 years of experience as a patient in the healthcare system. That includes being in large hospital settings, university training clinics, and small private practice. I've had the opportunity as a patient to experience a lot of different environments within audiology.

General Skills That Can Be Used with All Patients

Normalizing

The very first thing I wanted to discuss was normalizing. Take a second, pause to think about how often do you purposefully normalize information that your patients are giving you. I aim to normalize a minimum of four to five times in the course of a session, which might be 45 minutes. When you have a patient who is coming into your room for an audiology visit or checkup, they're often thinking about these issues that sometimes feel unique or specific to them. They don't interact with a lot of other people who have hearing loss, typically. Thus, it may be an uncomfortable topic to talk about. Sometimes patients may be feeling anxious or nervous in discussing their experiences. If any of you have ever gone to a medical specialist for your health, think about that feeling of walking into the waiting room and waiting to meet the doctor. You are nervous, wondering what they are going to say. You don't know what the course of treatment is going to be, and it's an anxiety-inducing process. In those moments, using normalization can be helpful. Normalizing is one of the most powerful tools you can use. Patients are often wondering if their problems are unique to them. Normalizing results in disclosing anxiety/discomfort for further discussion. Examples of normalization include:

- "A lot of children will say.."

- "Many others frequently tell me"

- "Given your level of hearing loss, I would expect it to be…"

- "This is very common among others with hearing loss"

I would challenge you, as providers, to think about how often do you make an effortful and purposeful point to normalize with my patients? Think about how often you are purposefully and effortfully normalizing what your patients are sharing with you, to make them feel comfortable and to build an alliance in the room.

Reflective Language

The next strategy I want to discuss is reflective language. This is thinking about how am I communicating with my patients or families? Are you actively listening and paying attention to them? I have seen many times with audiologists I've worked with in the past and even for myself, that we see the schedule for the day and feel overwhelmed. You have this whole list of things that we need to do. At times, it's easy for us as providers to not be present in the room. Thus, engaging in some form of reflective language is going to show your patients that you are actively listening to them and hearing the information that they are sharing with you. Examples of reflective language include:

- –"If I understand you correctly…"

- –"It sounds like…"

- –"What I am hearing is…"

- –"I get the sense that…"

- –"It feels as though…"

Every one of these is a way for me to reflect back to the patient the information that they gave me. Ask as few questions as you can and, instead, offer as many reflections as possible. Reflective language is a way to get more information without asking questions. Patients will then provide corrective feedback and information to tell me what I need to know. Either way, I am going to feel confident that I am on the right path in terms of understanding the information they are presenting to me. Or, I'm going to get corrective feedback and get to the right path. In the process of doing that, making them feel like they're heard and understood. It's a straightforward and easy technique, but it would elicit a lot more information from you in more of an open-ended way. Think about when we ask questions. We often use them in an upturn. "What do you want for dinner?" There are ways to take those questions and change them into a downturn. "I'm thinking about dinner." Or, "What do you want to do with the FM system? Do you want to keep using it?" Or, "So the FM system is a challenge for you?" There are ways to use that reflective language and build on that and get more information from them.

Avoid Finger-Wagging

Reactions to Lecturing

When we are experiencing finger-wagging, a typical response is to become defensive and feel closed off. In this instance, patients may justify or explain their current views. They're going to feel misunderstood. When we get into that finger-wagging mode, we are lecturing them in a way that is going to make them defensive, become closed off, and not want to engage.

Resistance. So what do we do with that? In sum, what we are experiencing is resistance. If you find yourself experiencing that resistance, there are ways to address it. Gather more information. If you find yourself doing all of the talking and telling them what they should be doing, stop, and ask them, "What's going through your head? "What are you thinking?" The second they give you that information, I would turn around and say, "Thank you so much for sharing that with me. I appreciate you letting me know." I'm going to encourage them and praise them for doing that. Get some more information and figure out if there's a middle ground that can be had. Maybe we can elicit a discussion between the child and her family about what is going on.

How to Provide Information

I am not saying that we should never give information about the standard of care, or what the best practices are. We absolutely have to do that. I am just encouraging you to be mindful of it and helping them navigate whatever challenges are coming up. Certain ways to provide information includes, asking permission. When we provide information, I love to get permission to increase "buy-in". "Is it okay if I tell you a little bit about some strategies that might be effective for you?" One of two things is going to happen. They're either going to say, "Yes", or they're going to say, "No." If they say, "Yes", then they're pretty much obligated to listen to you. The second someone permits you to give them more information, they're going to be more likely to receive that information. If they say, "No", which I will tell you, in my experience, is relatively rare. They are not in a place where they were ready to receive that information anyways. They were not going to engage in any sort of behavior change. If a patient is already at the point where they're just saying, "I don't even want to hear it", then you are better off preserving that alliance with your patient, saying, "You know what? I appreciate your honesty. Let's touch base next time and talk about more strategies." When we ask permission, what we're doing is making people feel like they are in control of their visit. We are acknowledging that patient as an expert in their own life, in their own experiences and working in tandem with them to figure out how we can best come up with a solution, or give them information and help them move forward.

Go back to the reflective listening statements. All of those phrasings are designed in a way to help that patient feel like they are in control and that they are valued, and they have valuable information to contribute to their visit. Hopefully, as you're thinking about these things, it's getting you thinking about some of those complex families or patients you've dealt with and wondering how you might be able to change those interactions. We don't want to be the finger-wagger. The education in and of itself does not work. So we're going to get into more examples of how to get around that and kind of motivate them a little bit. But know that simply providing information, is not going to elicit change.

Also, a reminder, we're not just treating the ears. It is easy to get caught up in all of the things that we have to do for our day and all the patients we have to get through, all the notes we have to write, all the billing stuff we have to do, all of the documentation we have to submit for molds and such—but pausing and recognizing that you need to be present with your patient, and then treating them and acknowledging them as a whole person and not just a set of ears that we are triaging when they come in the room.

Patient's Identity

Effects of Hearing Loss in Adults

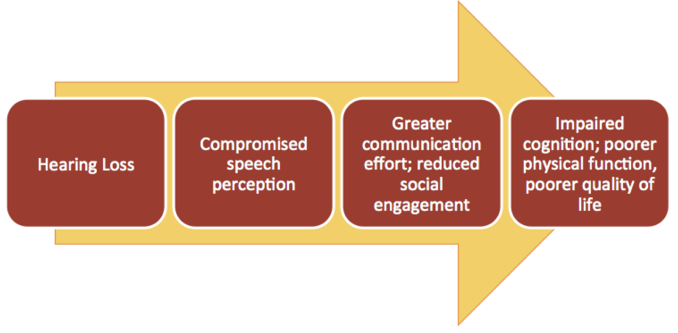

Hearing loss has significant psychological effects across a lifespan (Abrams, 2017). Figure 1 shows a chart highlighting how hearing loss impacts the entire person and cover the whole spectrum. Someone who experiences hearing loss will experience some sort of compromised speech perception, which is going to require a greater communication effort, reduced social engagement, impaired cognition, poor physical functioning, poor quality of life. Something starting from the ears can have this incompetent, long, caring effect across the entire life span.

Figure 1. Effects of hearing loss in adults.

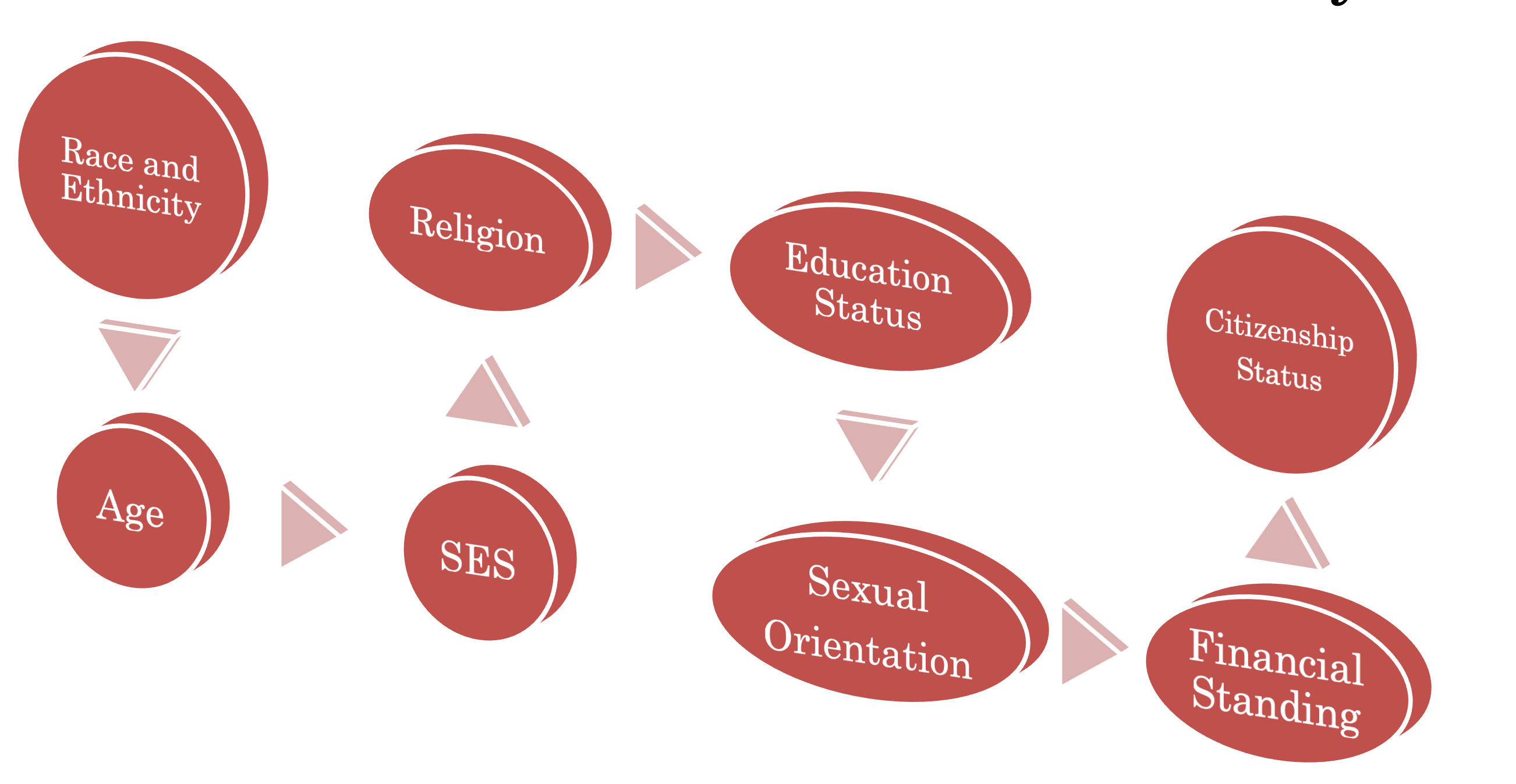

Role of Multicultural Identity

This is an important piece we should be thinking about all of the time. Addressing multicultural identity in an appointment is likely to facilitate a discussion of how the patient’s background and lived experiences are impacting them. Figure 2 shows different areas of multicultural identity that we should be thinking about and reflecting on. There are lots of various factors that come into play. I may be serving a family that is a person of color, or with a complex medical diagnosis, maybe they are a family that doesn't have legal documentation status in the United States or are on some sort of Medicaid or welfare. All of these other things are factors when dealing with patients and families in the room.

Figure 2. Different areas of multicultural identity.

I don't know how often we pause and think about the role of multicultural identity with our patients. If you are experiencing resistance, I would encourage you to think about this component. What multicultural factors might be playing a role? I am going to draw on the clinics that I've worked with, for example. The vast majority of the audiologists that I've engaged with are female, and they are white. That does not match up with the vast majority of patients that we see. In Miami, a large percentage of our patients were Hispanic and Haitian. Even here now in Delaware, a lot of them are African American. We have Asian families that come in as well. There are lots of cultural differences that might be at play. If I don't acknowledge or recognize how some of those things might be influencing the room, then I could miss an opportunity for intervention. Considering citizenship status, for a second. We may be talking to a family or a patient about all of the different resources that are available to them through the state and various private funding agencies. That patient may not be capable of receiving access to those things, if they don't have legal status, here in the U.S. So thinking about how these things play a role and engage with your patients is essential.

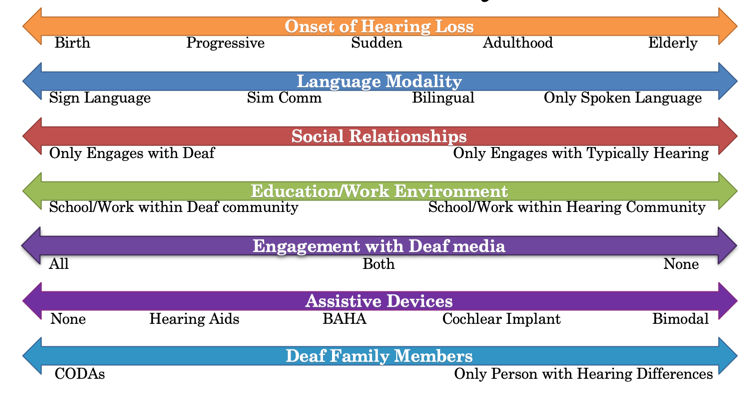

Duality of Deafness & Deaf Identity

Another component we need to consider as clinicians is the duality of deafness. Not every patient you see will identify with the deaf cultural group. Then there are those who don't identify as deaf at all. I think this creates an unfair dichotomy of those who identify as deaf, those who sign, versus those who don't. Figure 3 shows different areas in which deaf identity may play a role for a patient. Thinking about all of these various factors or levels, that a patient experiences when they come into your room. Was it onset progressive? Was it sudden? Was it at birth? Was this acquired in adulthood? What is their language modality? Are they sign? Are they SimCom? Are they bilingual? Are they only spoken language? Do they engage with anybody else who might identify as deaf or hard of hearing? Stay engaged at all with deaf media or deaf culture? What assistant devices do they use? Do they have any deaf family members? These are all different areas in which a person's identity, particularly as it pertains to hearing loss or being deaf, is going to change. How often are you thinking about these factors for your patients and if they are playing a role in the room?

Figure 3. Deaf identity.

Engaging Patients in Behavior Change

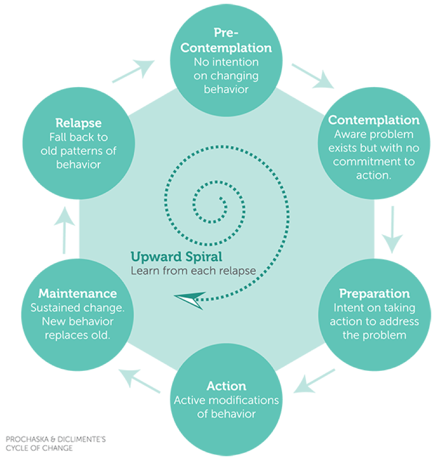

Figure 4 shows the Prochaska and Diclemente's Stages of Change (1983). This is one of the pre-eminent, most popular models of thinking about behavior change in healthcare. This was created and developed specifically within the idea of physical health change, particularly smoking cessation. Prochaska and Diclemente created essentially six different stages of behavior change.

Figure 4. Prochaska and Diclemente's Stages of Change, (1983).

Pre-contemplation. That is, "I am not even remotely thinking about engaging in any sort of behavior change." "The thought of it is not even on my mind." This might be a friend who is complaining about their significant other. "He or she cannot hear anything, and I've been begging them to go and get their hearing checked and possibly get a hearing aid." "They won't even bother to let me schedule an appointment." That would be someone who hasn't even remotely thought about engaging in any sort of behavior change related to their hearing.

Contemplation. You are aware that the problem exists, but there's no commitment to action. In that same example of the significant other, maybe now they recognize that their hearing is causing some problems. This is particularly true when they go out, to say a restaurant or to dinner, or when they're with their family. But they haven't thought through any sort of steps to possibly remedy that. I'm sure many of us audiologists probably had patients who come in, and they're like, "Yeah, my significant other brought me in. "I don't want to be here." Maybe they say it bluntly like that, perhaps they don't.

Preparation. This would be a patient who is now intent on taking action to address a problem, but they haven't taken any steps. "Yeah, I'm going to schedule an audiology appointment." Or, "I'm open to getting hearing aids. We already met with the audiologist, but we haven't submitted the order for them", "or haven't given them the go-ahead to get the devices." So they're thinking about taking action, they want to take action, they're probably going to take action within the next couple weeks, but they haven't done so yet.

Action. "All right, now I'm ready to engage in some behavior change, and I'm actively doing that." "I'm wearing my hearing aids a little bit more." "I'm trying a new FM system." Something to that effect.

Maintenance. "I've engaged in behavior change, and I am now maintaining it and going forward." The patient may have done this behavior change for a year or two now.

Relapse. This would be falling back into that old pattern. It applies differently to different situations. For example, drinking or smoking cessation, you can think about relapse very easily. With hearing loss, it might be something like they were wearing their devices more, and now they're not. Where we run into challenges as providers sometimes is we might have patients that are in the contemplation stage or the preparation stage, but we are talking about engaging them in ways that are over here in the action stage. Maybe a patient comes in, and they're thinking about getting hearing aids for the first time or thinking about a cochlear implant. But we are already talking about the next steps, in terms of action and setting up surgery dates and getting the MRI and all of that. But that patient does not want to move forward, they're not ready. If you are experiencing resistance with a family, one of the things I might ask myself, or yourself is, "Where in this stage of change model is my patient?" If they are not over here in the action phase, or preparation phase, "What can I do to help them move a little further along this spectrum?"

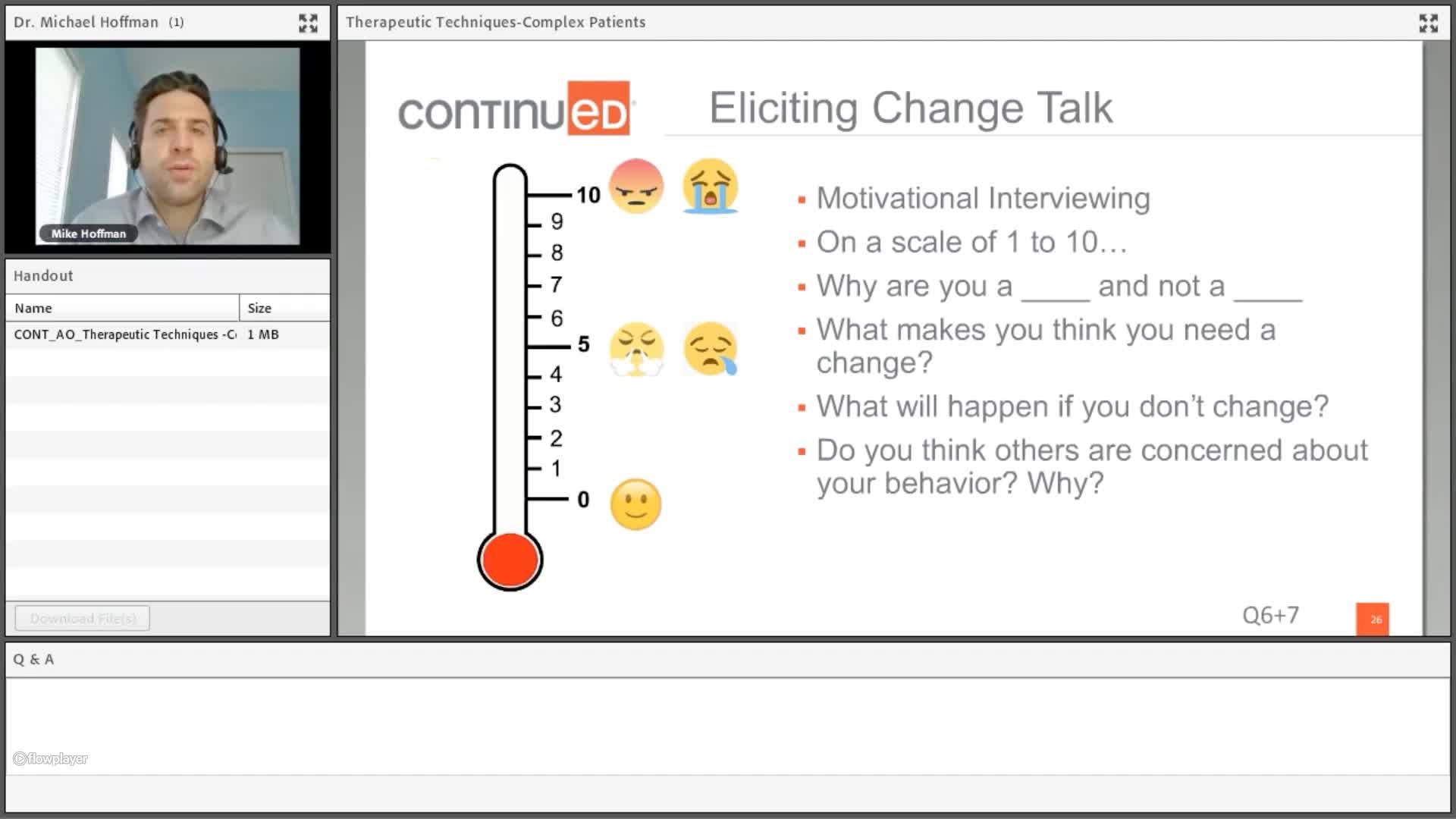

Eliciting Change Talk

Motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing is a process whereby we are acknowledging that there is some sort of ambivalence that is going on within a person, regarding a behavior change. In the case of possibly using hearing aids more frequently, or getting an implant, there is usually some sort of ambivalence that is going on there. Motivational interviewing is a way of increasing that ambivalence to help a person be ready to move on some behavior change. There's a book about motivational interviewing. If you're interested in learning more about that, I would suggest reading it. It is not explicitly written for psychologists. It is written specifically for healthcare providers.

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2012). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford press.

I'm going to walk through this example of what I find to be one of my most challenging types of cases. Hopefully, it will get you thinking a little bit about this. Probably different than conversations you might usually have with a patient.

So a few things I did here. When I asked, "Why are you a two or a three, and not a one?" What that does for a patient, is forces them to explain in their own words, why hearing aids might be helpful for them. We know from health behavior change that people are more likely to engage in a change when they are discussing the reasons that they need to make a change, not hearing it from us as providers who are lecturing at them. I got him to talk a little bit about the reasons why he wasn't a one. Also, I said, "Hey, what can I do to get you to a five or a six?" I was asking, "What do you think you need, what can we do to help you make a change?" All of these things were pulling information and getting data that I can use to adjust either the programming of the hearing device, maybe the FM system, or think about other sources for referrals.

Other questions that I didn't build in here. "Well, why do you think others are concerned about your behavior?" So if a patient tells you, "Oh, I don't know, I just don't want to wear them." Say, "All right, that's fair. Could you tell me, why do you think your mom is so bothered by this? Or why do you think this is so frustrating for your dad?" Again, I'm using that same strategy that I used previously. I'm getting them to talk about reasons why they might want to improve or change their behavior. This is not easy. This is a difficult way of engaging with patients, and it probably feels different from the way that you have done that previously.

New Diagnosis Families

When we have newly diagnosed families, we need to put ourselves in the perspective of that family. We know that many of them are experiencing guilt, or they're mourning that kind of change in the expected trajectory of this child's life course. They just don't know what's going on, and they're not sure how this hearing loss is going to impact the person. It may be that the thought of acknowledging or recognizing this is painful and hurtful for them. What I've experienced from a lot of families are a lot of questions, not only around technical issues and aids and technology but social functioning. Will my child make friends? What will others think about them? Will they ever date? Will they get married? When we have these new diagnosis families, even one who might be In denial, I think it requires a slight shift in thinking. It feels minor, but I think it can go a long way.

Our goal shouldn't be to make them feel better. Instead, our goal should be to make them feel heard. If we think of ourselves as trying to make them feel better, then what we're doing is closing the door for that family to express what they're going through by trying to rush them to a better or happier space. The family may not be there yet. I'm going to normalize and validate those feelings. Many parents often describe to me that this feels like a loss. The things they imagined for their child are changing. I'm going to use reflective language as this communication strategy can be helpful.

Again, you're going to elicit more information this way. What I do want to avoid with new diagnosis families, is specifically targeted information. It's not going to result in more information or engagement. I don't want to ask close-ended questions, where you're just pulling for a yes or no response. I don't want just to bombard the family with my previous professional experience.

Citation

Hoffman, M. (2020). Therapeutic techniques to build alliance with complex patients and their families. AudiologyOnline, Article 27021. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com