Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Social Determinants of Health and Audiology, presented by Laura Coco, PhD, AuD, CCC-A.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Define social determinants of health in healthcare and their relevance to audiology.

- Describe the importance of screening for social determinants of health in hearing healthcare.

- Identify methods for identifying and assessing individual social risk factors in hearing healthcare settings.

Outline

This class serves as an introduction to the social determinants of health. I understand that many of you might already have some knowledge in this area; however, this session aims to establish a foundational framework, providing a clear definition and baseline understanding of the topic. I hope that it won’t be too basic for anyone. Like many of you, I did not receive formal education on this subject during my AuD program, so I am approaching this with the assumption that you may be in a similar position.

Today’s outline includes a brief personal introduction, followed by a definition of social determinants of health and their relevance in audiology. I will also discuss identifying and addressing unmet social needs before exploring future directions and potential developments in this area. Finally, I will summarize the key points.

Brief Personal Introduction

Let me introduce myself and explain why I’m interested in the social determinants of health and how this topic influences my work as an audiologist and researcher. I am a CODA—a child of a deaf adult. My dad was born with hearing loss, which progressed to profound deafness as he grew older. This deeply shaped my perspective and has been a guiding influence in both my practice as an audiologist and my research. Sign language was my first language, so I always begin talks by acknowledging that I am a CODA. This identity informs my understanding of social determinants of health and is my primary inspiration for becoming an audiologist.

My journey toward audiology began when I volunteered at a clinic in southern Mexico, even before I started my clinical audiology training. It was there that I encountered, up close, the significant challenges and barriers faced by rural, underserved, and low-income patients seeking hearing healthcare. When I returned to the United States and began graduate school, I realized that many of the same barriers exist here, albeit sometimes to a lesser degree. Recognizing these shared obstacles, I began to develop solutions and strategies to improve access to care.

One of the key solutions I focus on is telehealth. During my AuD program at the University of Texas, I was involved in a telehealth initiative that was part of a research program but also served clinical patients. We provided remote hearing aid services to these patients while fitting hearing aids for patients in San Antonio, bridging the gap for those who struggled to find local care. Telehealth remains a strategy I rely on today to address access barriers.

After completing my AuD program, I pursued a PhD at the University of Arizona, where my mentor specialized in community-engaged care. We collaborated with community health workers who delivered a hearing health education program and essential services in communities lacking local audiologists. My dissertation combined these two approaches—telehealth and community health worker partnerships—to address access barriers more effectively.

I am now an assistant professor at San Diego State University, where one of my key projects focuses on preventing hearing loss among farmworkers in rural areas. Two of my graduate students and I held a health fair for farmworkers at night. We had lanterns that were necessary because it was pitch dark and freezing cold, but this was the only time these workers could receive health services. Meeting participants where they are—literally and figuratively—is crucial to overcoming barriers to care.

What Determines a Person's Health Outcomes?

Now, let's move on to the basics—the nuts and bolts—of social determinants of health. Our health outcomes are influenced by a wide range of factors, not just by biological aspects and the treatment we receive in healthcare settings but also by non-medical factors.

To illustrate this, let’s start with an example. Imagine two patients with the same chronic condition, such as diabetes. Adam has access to comprehensive medical care. He lives in a safe neighborhood, has a steady income, and enjoys strong social support from family and neighbors. He can afford nutritious food, has time for regular exercise, and effectively manages his stress.

In contrast, Dan also has diabetes but faces very different circumstances. He lives in a low-income area with limited healthcare facilities. His neighborhood is unsafe, making outdoor exercise difficult. He struggles to afford healthy food and often relies on less nutritious options. Financial instability and a lack of social support add significant stress, which further exacerbates his condition.

Here, we have two individuals with the same chronic condition—diabetes—who might receive identical medical treatment. However, Dan experiences poorer outcomes, more frequent hospitalizations, and worsening health. This example highlights how environmental and social conditions can significantly impact health outcomes.

When considering the factors influencing a person’s health outcomes, research shows that it goes far beyond biology and the treatment provided in a healthcare setting. It’s estimated that 40% of health outcomes are determined by an individual’s socioeconomic factors, while 10% can be attributed to their physical environment—such as the conditions in which they live. Additionally, 30% is influenced by health behaviors, like smoking, exercise, and diet. Surprisingly, medical care accounts for only 20% of health outcomes, encompassing interactions within healthcare settings.

This is important to remember when patients enter our clinic, as we often assume that their outcomes are entirely within our control. The next two examples highlight different patient scenarios in an audiology clinic.

First, we have Alice. She is well-resourced with a high-paying job and excellent health insurance coverage. Alice can afford premium hearing aids and has the financial means to attend regular follow-ups with an audiologist. She lives in a quiet suburban area with minimal environmental noise exposure, and her workplace has implemented noise reduction measures. Alice can purchase and prepare healthy meals, exercises daily, and doesn’t smoke. While these factors might seem unrelated to audiology, they are significant, reducing potential risk factors for hearing loss. Additionally, Alice has access to high-quality medical care and receives timely treatment and follow-up care.

On the other hand, consider another patient, Debbie, who comes in the next day. Debbie works a low-income job at a factory and lacks health insurance. She has accumulated significant debt from medical bills after a recent accident and relies on public transportation, which can delay her follow-up visits. Most of her paycheck goes toward rent. Debbie has smoked cigarettes for the past 30 years and doesn’t have a regular primary care provider, only seeking medical care during emergencies.

Like the previous example of the diabetes patients, even if we provide the same treatment, recommendations, and care to Alice and Debbie, their outcomes will likely differ due to the disparities in their social and environmental circumstances.

Definition of Social Determinants of Health (SDOH)

Let’s define social determinants of health. Simply put, they are the environmental and lifestyle factors that influence health. For a more comprehensive definition, according to Healthy People 2030, social determinants of health are "the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks." These determinants are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources and are influenced by factors like institutional bias, discrimination, racism, and more. Understanding social determinants of health is crucial for addressing health disparities and promoting health equity.

Five Key Areas of SDOH

Social determinants of health can be categorized into five key areas or "buckets." These are healthcare, including access and quality; neighborhood and the built environment; social and community context; education, including access and quality; and economic stability. Each of these areas includes specific factors that influence health outcomes. Let’s begin by delving into each area, starting with healthcare.

Healthcare

Healthcare encompasses several important factors, starting with insurance coverage, which ensures access to necessary medical services. Another key factor is health literacy, defined as the ability to understand and use health information effectively. Transportation to healthcare facilities and services is also crucial for accessing care. Provider availability is another consideration—are there enough healthcare providers and specialists in your area? Additionally, patient-provider linguistic and cultural congruence is essential. This refers to how well the provider’s language and cultural understanding align with the patient’s needs, which can significantly impact the quality of care.

Neighborhood and Built Environment

Next, the neighborhood and built environment encompass several factors. These include the safety and quality of housing, access to reliable transportation, and water and air quality, which are crucial for reducing health risks. Other important aspects are crime rates, the availability of parks and playgrounds, and the overall walkability of the area.

Social and Community Context

Social and community context includes factors like social integration and community involvement, which contribute to a sense of belonging. Support systems, such as the availability of friends, family, and community support, are also critical. Additionally, this area covers community engagement, experiences of discrimination and stress, and broader issues like racism and stigma.

Education

Education is a critical determinant involving literacy and language skills, early childhood education, vocational training, and higher education opportunities.

Economic Stability

Finally, economic stability factors include employment status, stable jobs with fair wages, income levels to meet basic needs, expenses and debts, medical bills, and financial support.

SDOH and Layers of Determinants

Social determinants of health are powerful predictors of health and healthcare inequities, shaping disparities and outcomes across different populations. By understanding the multiple layers of these determinants, we can better address and mitigate health inequities. This understanding also equips researchers and clinicians to plan and implement interventions targeting various influence levels.

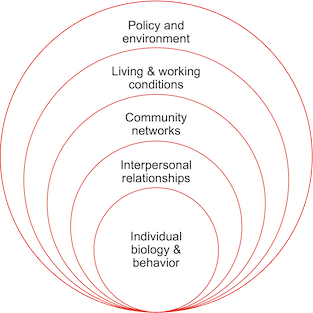

Figure 1 shows a socioecological model some of you may be familiar with. This model provides a framework for understanding the multilevel, multifaceted, and interactive effects of personal and environmental factors on behavior and health outcomes. The model illustrates multiple levels of influence, starting with the individual at the base and progressing upward to include policy, environmental, and societal factors.

Figure 1. Layers of determinants.

These layers interact and complement the social determinants of health, providing a deeper understanding of how the environment influences health outcomes. We can consider how personal characteristics and behaviors impact health at the individual level. For example, in an audiology context, this includes biological factors, personal knowledge, and attitudes—such as awareness of hearing loss, knowledge about hearing aids, and personal health behaviors related to hearing care.

Moving up one level, we examine interpersonal relationships, including family and friend dynamics, the support and encouragement individuals receive, and the influence of peers and social norms. For instance, family support and social acceptance of hearing aids can play a significant role in whether someone seeks help or uses hearing aids.

At the community level, the focus shifts to relationships among organizations, institutions, and informal networks. This includes community programs to improve health, shared beliefs and norms regarding hearing loss and hearing aid use, and available resources and hearing aid providers within the community.

One level higher is the living and working conditions layer, which covers workplace safety regulations that protect against noise-induced hearing loss, economic stability affecting the ability to afford hearing aids, and environmental noise levels in both work and home settings that can impact hearing health.

At the top level, we find policy and environmental factors, including local, state, and national policies and laws, that influence hearing healthcare. Examples include healthcare policies, insurance coverage and reimbursement for hearing aids, government funding initiatives, and laws like the Americans with Disabilities Act that protect the rights of individuals with hearing loss.

These layers don’t operate in isolation; they interact and shape outcomes and behaviors. For example, a policy change, such as improved insurance coverage for hearing aids, could influence community attitudes, leading to greater acceptance of hearing aids at a community level. This, in turn, could increase interpersonal support from family and friends, ultimately leading to more individuals seeking help for hearing loss.

As you can see, these layers interact dynamically and closely mirror the social determinants of health.

I want to pause here and encourage you to reflect on how the social determinants of health might play out—positively or negatively—at each level of influence. It may be helpful to consider an example from your life, even outside of audiology.

For instance, at the individual level, positive determinants of health might include exercising daily, scheduling an annual dental checkup, or eating nutritious food. Moving up to the community level, your ability to exercise daily could be influenced by factors such as whether your neighborhood has safe sidewalks, public parks within walking distance, or a nearby gym. Do you feel safe and have the resources needed to exercise daily?

If we jump up to the policy level, broader factors come into play, such as whether you can afford a gym membership or earn a fair wage that allows you to meet your basic needs, like rent, while still having time for activities like exercise. This demonstrates how the different levels complement one another and shape our overall health and well-being.

By understanding these concepts personally, we become better equipped to relate to and empathize with patients navigating similar challenges in their own lives.

SDOH and Hearing Care

Social determinants of health significantly impact hearing aid uptake by influencing access to care, awareness, affordability, and social support. These determinants encompass a range of factors, including economic stability, education, social support, and community context. Let’s look at a few examples from the literature that illustrate the impact of social determinants on access to audiology services.

Research has shown that individuals with higher socioeconomic status tend to have better hearing thresholds. Additionally, those with more years of education are more likely to have had a recent hearing test. Studies also reveal that individuals of white race are more likely to report regular hearing aid use. Conversely, rural residents often experience delays in accessing hearing care compared to their urban counterparts. Furthermore, individuals without private insurance are less likely to have hearing aids than those with private insurance. Lastly, individuals with higher socioeconomic status are more likely to be referred for tympanostomy tubes to treat otitis media.

Overall, the literature consistently demonstrates that social determinants of health influence how people become susceptible to, are diagnosed with, and receive care for hearing loss.

We all likely recognize that while hearing loss is common, hearing aid use remains much less common. Among adults over age 70 who are audiometrically eligible for hearing aids, less than a third use them—well below what we’d hope. Hearing aid use is influenced by several factors which, at first glance, may not seem directly related to social determinants of health. However, a closer examination reveals that many of these factors are connected to social determinants.

First, there is the more obvious factor: cost. Cost is a significant barrier to hearing aid uptake and is directly linked to social determinants of health like economic stability and healthcare access. Another factor is self-reported hearing disability. You might wonder how this is related to social determinants of health, but it could be indirectly influenced by health literacy and access to healthcare.

Perceived benefit is another factor associated with low uptake of hearing aids. Some individuals may feel that their self-reported hearing loss isn’t severe enough to warrant hearing aids. This perception can be indirectly connected to social determinants of health through education and health communication. Effective communication from healthcare providers and public health campaigns can shape perceptions of benefit.

Degree of hearing loss is primarily a biological factor, and as a clinical measure, it is less directly influenced by social determinants. However, early detection and management could be influenced by access to healthcare, so there is still a possible association with social determinants.

Stigma is another important factor that could be linked to social determinants via social and community context, cultural beliefs, and social norms of hearing loss. Community and peer attitudes can reduce or heighten the stigma surrounding hearing aid use.

Lastly, age may not initially seem related to social determinants of health, but it can be indirectly linked through healthcare access. Older adults may experience varying levels of access to healthcare, and age can also influence social support networks, affecting hearing aid uptake.

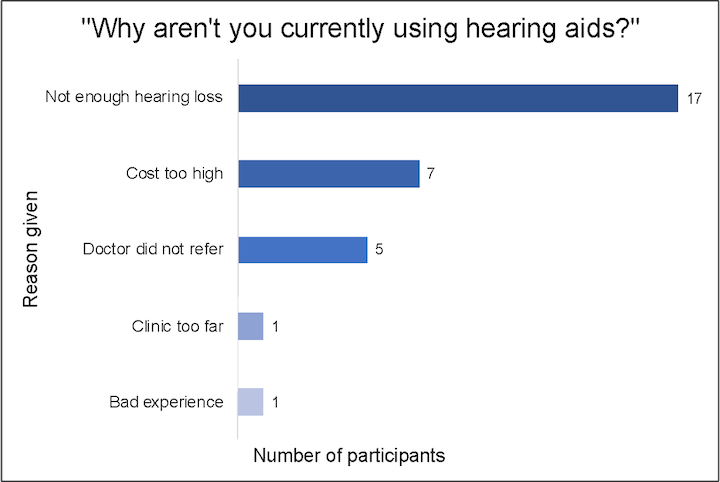

Figure 2. Reasons for not using hearing aids.

Figure 2 presents the results of a study we conducted. The full findings are published in Ear and Hearing if you want to explore them further. These results come from a group of older adults living in southern Arizona along the U.S.-Mexico border. Most participants reported annual incomes of $10,000 or less. All identified as Latino, and the majority were Spanish-speaking. None of them had used hearing aids at the time of the study, which involved fitting them with hearing aids as part of a randomized controlled trial.

At baseline, we asked them why they weren’t currently using hearing aids. The majority responded, "I don’t have enough hearing loss." This aligns with what we discussed previously regarding self-reported disability; they didn’t perceive their hearing loss as significant enough to justify purchasing hearing aids. Other common reasons included the high cost, lack of a doctor’s referral, distance to the clinic, and past negative experiences with providers.

These findings highlight, once again, how access to and use of hearing aids are often tied, directly or indirectly, to social determinants of health.

Barriers in Audiology

Geographic barriers also play a significant role in limiting access to hearing care. According to ASHA, there are an average of only four audiologists for every 100,000 people in the United States, which seems quite low to me. Even more concerning, these audiologists are not evenly or equitably distributed nationwide. Many rural areas and other parts of the U.S. have no audiologists, meaning people in these regions face long drives or may choose not to seek care because there is no representation in their community.

In an article by Pliny, she found that counties with older populations and lower family incomes tend to have fewer audiologists. What’s particularly interesting is that audiologists are often clustered around cities with AuD programs, which makes sense, but these programs are typically located in major cities. As a result, patients in smaller towns may not even be aware that audiologists exist—if they don’t see it, they might not know it’s available. Additionally, Chan et al. found that patients in rural areas experience delays in accessing hearing aid services compared to their urban counterparts.

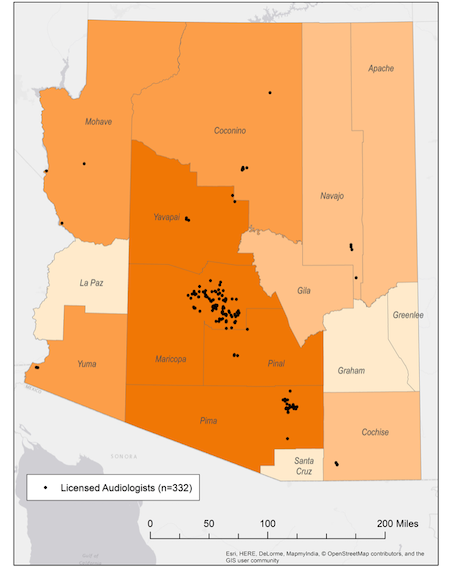

Arizona Case Study

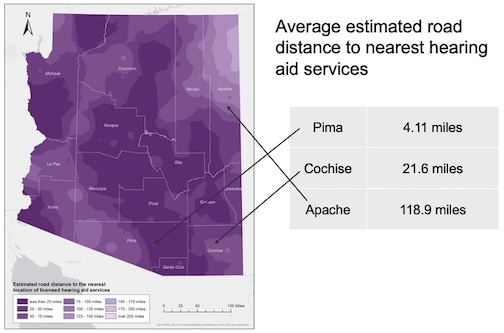

This is a study we conducted in 2018, focusing specifically on Arizona. We mapped out audiology clinic locations with population density as the base layer. In Figure 3, the darker areas represent more densely populated counties, while each black dot represents an audiology practice. As you can see, there’s a large concentration of practices near Phoenix and a smaller cluster around Tucson. However, vast parts of the state have no audiology practice locations. Among Arizona’s 15 counties, six have no audiologists, and the driving distance to the nearest clinic can exceed 100 miles.

Now, imagine a patient living in the northeastern region, like in Apache County, facing a 100-mile drive just to see an audiologist. On top of that, they may be dealing with additional barriers such as cost and stigma, making it understandable why someone might opt out of seeking care altogether.

Figure 3. Map of audiology clinic sites in Arizona.

Figure 4 shows some examples of the average drive times to the nearest audiology services within a few counties. In Pima County, it’s fairly manageable, with an average drive of about 4 miles. In Cochise County, that distance jumps to around 22 miles. But if you’re in Apache County, you’re looking at over 118 miles to reach the nearest audiology clinic.

Figure 4. Estimated road distance to nearest hearing aid services.

Identifying Unmet Social Needs

Identifying unmet social needs is important, and it’s worth distinguishing between the terms "social needs" (or "health-related social needs") and "social determinants of health." Although these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they are not exactly the same. I may use them interchangeably in this course because many screening measures are labeled as "social determinants of health" screenings, but there is a slight difference.

As I mentioned earlier, social determinants of health refer to the broader conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age—operating more at a macro level. On the other hand, social needs are more focused on the individual level and can be understood as the results of those broader social determinants. Social needs include housing instability, housing quality, food insecurity, employment, and personal safety.

Next, I’ll discuss what our role as audiologists is and how we can identify these unmet social needs.

One approach is to administer a standardized social determinants of health screening questionnaire. Another key method is to engage in empathetic inquiry and active listening, using patient-centered communication to build trust, understand patient needs, and ensure that patients feel heard and respected.

Screening Tools

Now, we will focus on screening tools that can be integrated into your workflow to identify and address social needs, with referrals to community-based resources. These screening tools may be relevant for you depending on your work setting—whether in a large hospital or a small private practice. It’s ultimately up to you to determine if it’s appropriate to incorporate these tools into your practice. You might even decide to take just one or two questions from these formal tools and integrate them into your routine. My goal is to introduce these resources, highlight their availability and usage in other contexts, and then leave it to you to decide how to proceed.

Responsible screening is essential. This means putting patients at ease, ensuring confidentiality to obtain honest responses, providing information in accessible formats, and maintaining strong relationships with community partners. It also involves training staff—or yourself—to address sensitive topics competently and ensuring that your community partners have the capacity to handle referrals.

Here are a few recommendations for conducting responsible screening. First, conduct a needs assessment, which can vary depending on your context and available resources. A needs assessment could be as simple as researching community statistics, such as income levels, poverty rates, and rurality, and comparing those with the patient population you currently serve. Understanding the demographics of your population will help you identify the relevant community connections to establish and select appropriate questions or formal assessment tools. This preparation occurs even before you begin screening.

Additionally, before screening, it’s crucial to establish relationships with community resources, as you’ll need to know where to refer people when unmet needs are identified. Once those relationships are in place, select a screening instrument—or relevant portions of one—and train your staff to address these topics while ensuring that community partners are equipped to receive referrals.

When conducting screenings, putting patients at ease and ensuring confidentiality is critical. A private area is more appropriate for orally administering a questionnaire, while self-administered questionnaires might be fine in a waiting room. It’s also helpful to preface the conversation by saying something like, "We ask everyone these questions," which can ease concerns about being singled out. Before discussing the survey or results, the provider could engage the patient or family by asking, "Do you have any needs I could help you with today?"

Empathic Inquiry

Empathic inquiry is an approach to social determinants of health screening that emphasizes non-judgmental curiosity and understanding. The Oregon Primary Care Association offers a wealth of information on this topic. Here, I’ll cover the essential elements of empathic inquiry.

This approach helps avoid social desirability bias—where the patient may tell the provider what they think the provider wants to hear rather than being completely honest. Empathic inquiry also fosters a culture of sensitivity and respect, focusing on data collection and genuinely understanding your patients one person at a time. It prioritizes sharing power between the provider and patient, respecting privacy, and being transparent about what data is being collected, why, and what will be done with it afterward. It considers the influence of stigma and biases and avoids confusion. The process always ends with empathy, collaboration, and action planning—ensuring the patient is actively involved in determining the next steps.

Here is a guide for using empathic inquiry:

- Start building trust: Begin by introducing yourself and your role. If you, as the provider, are conducting the screening, introduce yourself accordingly. If a nurse, audiology assistant, or another team member is administering the survey, they should explain their role, the purpose of the screening, and how long it will take. Always ask permission to have this conversation and invite the patient to ask any questions before starting the questionnaire.

- Help create understanding: Use open-ended questions to better understand the patient’s situation. For example, you might ask, "How are things going with making ends meet?" or "Tell me more about what’s going on for you." Engage in reflective listening. If the patient mentions struggling with rent, you could respond, "It sounds like getting help with your rent is a top priority for you." Reflective listening demonstrates that you are truly hearing and understanding their concerns.

- Summarize, action plan, and support: Once you’ve gathered information about their top needs, summarize what you’ve learned and collaborate on an action plan. Offer specific support, like saying, "It sounds like you’ve been working hard to make ends meet." Acknowledge any gaps in available resources and discuss how the team can still use the information provided to support the patient’s health. Ask permission to follow up on their needs. For instance, if food insecurity is challenging, you might say, "What do you already know about food resources available in our community? We can help connect you." The conversation must remain collaborative, prioritizing the patient’s permission and comfort.

Empathic inquiry is an ongoing dialogue that builds trust, shares power, and keeps the patient at the center of care. It’s more than collecting data; it’s about forming a relationship and creating actionable steps together.

Screening Tools for Adult Patients and Pediatrics

There are various screening tools available to assess social determinants of health. The most well-known are the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PREPARE) and the Accountable Health Communities (AHC) screening tool. Both are accessible online for download. One advantage of PRAPARE is that it can be integrated into electronic medical records. It consists of approximately 20 questions, making it a relatively quick assessment. Depending on your practice setting, you may decide to incorporate specific questions from these tools into your workflow.

Social determinants of health for children differ from those for adults and include factors like maltreatment, food insecurity, parental substance abuse, and low maternal education. Therefore, the screening tools for children need to be different. One example is the IHELP Pediatric Social History Tool by Kenyon et al, 2007. Assessing social determinants of health in pediatric patients is crucial; research shows that up to 83% of pediatric patients—depending on the setting—experience at least one negative social determinant of health, such as inadequate or unsafe housing or food insecurity.

You may wonder how to integrate this screening into your workflow. Again, the approach will vary depending on your practice setting, but I’ll provide two workflow examples.

Workflow example #1:

Assign the responsibility of screening to a non-clinic staff. In a large hospital setting, you might collaborate with community health workers or patient advocates who can handle this responsibility. This approach has clear advantages, as these professionals often have their own office, may be trained in social work, and may already be connected to community resources. The screening could occur in the patient advocate's office before or after the clinical visit, with the patient advocate administering the screening, responding to identified needs, and discussing the results with the provider. It’s important to share the results with the provider, as they could impact the recommended treatment or expectations for care. If the screening happens after the clinical visit, the results would be reviewed and considered at the next follow-up appointment.

Workflow example #2:

The screening could be conducted in the exam room. In this scenario, an interpreter, audiology assistant, or office staff member could do it while the provider is finishing up with another patient. Before the provider enters, the screening or discussion takes place, and then there’s a brief conversation about how socioeconomic or environmental factors might influence care. Referrals to community resources are made before the patient leaves.

Why should we screen for social determinants of health? Is this within an audiologist’s scope of practice? Understanding social determinants of health allows us as audiologists to provide holistic care that addresses the clinical aspects of hearing health and the broader factors influencing a patient’s overall well-being. Identifying barriers like transportation issues, financial constraints, and lack of social support enables us to connect patients with resources and services that help them overcome these challenges.

Addressing social determinants of health can lead to better health outcomes by ensuring patients can adhere to treatment recommendations, attend follow-up appointments, and use devices like hearing aids or other assistive technologies correctly and consistently. Screening for social determinants also allows us to tailor interventions and recommendations to meet each patient’s unique needs. For example, we might offer telehealth options for those facing transportation challenges or provide educational resources at an appropriate level for patients with low health literacy.

By recognizing and addressing social determinants contributing to health disparities, we can work towards reducing and eliminating inequities in hearing healthcare. The data we collect on social determinants can inform policy and advocacy efforts to improve access to hearing care services.

When patients see that their audiologist understands and cares about their broader life context, it builds trust and encourages greater engagement in their hearing healthcare. This can lead to more effective communication and a stronger patient-provider relationship.

Addressing Unmet Social Needs

How can we address unmet social needs? While addressing the underlying conditions in which people live is often outside our scope, clinicians can still take steps to address the resulting health-related social needs by understanding which needs uniquely impact our patients and referring them to local community services. We can also partner with community leaders and make our own services more accessible. Here, I’ve outlined eight examples of actions we can take:

- Improve Access: Consider offering telehealth options for certain patients, incorporating a mobile clinic, or expanding hours to accommodate those who need early morning or evening appointments.

- Economic Support: Implement a sliding fee scale or collaborate with a patient navigator or social worker to help patients find financial resources to cover the cost of services.

- Education and Empowerment: Enhance health literacy by ensuring the materials you provide are appropriate for your patients' literacy levels. You could also hold community workshops to improve health literacy within your community.

- Build Partnerships: Strengthen referral networks by collaborating with community members and organizations, not just traditional partners like ENTs. Think creatively about who else in your area could be a valuable resource.

- Advocacy and Policy: Advocate for and support policies that help patients access services in the long term. Support and participate in public awareness campaigns.

- Cultural Awareness: Train your staff and yourself to provide culturally responsive care. Tailor your services to be more sensitive to the patient population and reflect your community's demographics, ensuring that your patient population represents the broader community.

- Supportive Environments: Make sure that your clinic is a supportive environment. You could establish community support groups or patient advocacy groups to create spaces for connection and empowerment.

- Identify Social Risk Factors: The key theme of this course is to identify social risk factors so that we can document patient needs and actively work toward addressing them. Gathering this data also helps us better understand where our patients are now, allowing us to tailor interventions and referrals more effectively.

My suggestion is not to tackle all eight of these strategies at once but to focus on one small change you can immediately implement. You might already be doing many of these things, which is fantastic. If so, I encourage you to spread the word and inspire others to act similarly.

Another important consideration is integrating social determinants of health into audiology graduate and undergraduate education programs. As I mentioned earlier, although I attended a fantastic program, I didn’t receive formal education on this topic, likely because it’s not included in AuD competencies. However, I strongly believe understanding these concepts is within our scope of practice. I only received formal training on social determinants of health through my public health education during my PhD.

If you’re an educator, consider teaching your students about social determinants of health through formal instruction or by incorporating them into demonstrations. Preparing future audiologists to address these factors will ultimately lead to more holistic and equitable care.

Advocating for Hearing Health Equity

Audiologists play a significant role in advocacy, which can positively impact healthcare access and quality and influence policies that affect social determinants of health. Here are some examples of how social determinants of health are applied in audiology and how you can contribute to advancing hearing health equity.

Engaging in advocacy at local, state, and federal levels is one critical avenue to support policies that improve access to hearing healthcare. Additionally, ensuring that your services are culturally and linguistically appropriate helps make care more accessible to diverse patient populations. Hiring staff members who reflect the demographics of the community you serve can further enhance your ability to connect with and support your patients. Educating patients about their eligibility for entitlement programs is another valuable way to remove barriers to care, as is collaborating with non-traditional partners who can help address broader social determinants of health. These are just a few examples of how audiologists can actively work to promote hearing health equity through advocacy and community engagement.

Addressing SDOH in Audiology

Here are a few examples from the literature that illustrate how social determinants of health are already being applied in audiology. I’ve included citations so you can explore these studies in more detail. The first study (Matiz et al, 2022) was a retrospective chart review of children with hearing loss whose caregivers were enrolled in a program that integrated community health workers into the medical team to identify social needs. Conducted in a large hospital center, the results showed that 93% of children had multiple social needs. At the three-month follow-up, 70% of families completed referrals, and a significant number obtained hearing aids or cochlear implants compared to baseline. The key takeaway is that integrating community health workers into the care team is an effective way to address social needs and improve follow-up care for children, although this approach may be easier to implement in larger health systems.

Another study (Findlen et al, 2024) involved a retrospective chart review of nearly 1,500 infants referred for diagnostic testing. The researchers examined how social determinants of health affected the time to diagnosis and provided social programs and care coordination to the families. Interestingly, they found no clinically significant differences in diagnostic delays related to social determinants of health factors. This suggests that when social programs and care coordination are in place, the negative impacts of social determinants can be mitigated.

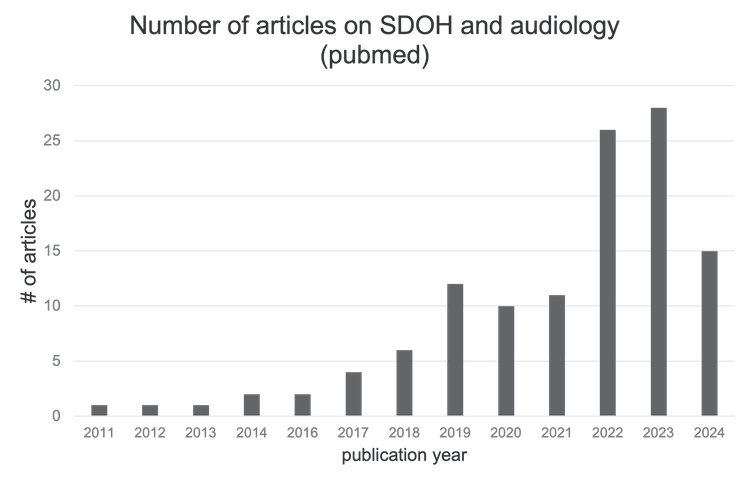

A final study (Nicholson, Rhoades, & Glade, 2022) worth exploring is a data review from the CDC’s Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) screening follow-up survey. It found that delays in diagnosing young children with hearing loss are associated with maternal age, education, and race. To illustrate the growing focus on social determinants of health in audiology, Figure 5 shows the number of related articles published each year. The graph highlights a marked increase in publications in 2022 and 2023, reflecting the increasing attention this topic is receiving. Keep in mind we’re only halfway through 2024, so it will be interesting to see how much more attention this topic receives by the end of the year.

Figure 5. The number of articles on SDOH and audiology.

Future Directions and Needs

As we look forward, I’ll wrap up by discussing future directions and needs. First, there’s a pressing need for more education and training in this area, so I applaud all of you for completing this course—you’re ahead of the curve. You probably already have some knowledge of social determinants of health, and now I hope you’ll continue spreading the word to your students and colleagues.

We also need increased community engagement and outreach, including partnerships with non-traditional allies, as well as interdisciplinary collaboration with community health workers and other community partners. It’s essential to step outside of our usual boundaries and think creatively about who we can work with to better address these issues.

Supportive policies are another key area, and to influence policy effectively, we need data. That’s why it’s crucial to screen for and collect information on social determinants of health. Speaking of policy, payers are beginning to factor in social determinants of health into their payment models. This topic alone could be an hour-long presentation, but briefly, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are shifting toward value-based payment models instead of the traditional fee-for-service models. Value-based care emphasizes quality and outcomes over specific services, making social determinants of health increasingly relevant.

Since social determinants play a significant role in patient outcomes, capturing this data can help document their impact. CMS has even started reimbursing some providers for services related to social determinants of health, including screening and community integration, though audiologists are not yet covered. However, there’s potential for this to change in the future. That’s why it’s so important to familiarize ourselves with social determinants of health and screening practices now, so we’re prepared for what’s ahead.

As someone who teaches both undergraduate and graduate students, I’ve noticed a lot of interest in this topic among students. This gives me hope that we’ll see a future where social determinants of health are formally integrated into graduate education. With audiology—and healthcare in general—shifting towards a more patient-centered and holistic approach, social determinants of health naturally fit into that evolving framework. The growing interest among students is a clear indication that there’s a demand for this kind of training, and it’s exciting to think about how this could shape the future of our field.

References

Arnold, M.L., Hyer, K., Small, B.J., et al. (2019). Hearing aid prevalence and factors related to use among older adults from the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg., 145(6),501–508. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0433

Blackwell, D. L., Lucas, J. W., & Clarke, T. C. (2014). Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: national health interview survey, 2012. Vital and health statistics. Series 10, Data from the National Health Survey, (260), 1–161.

Coco, L., Carvajal, S., Navarro, C., Piper, R., & Marrone, N. (2023). Community health workers as patient-site facilitators in adult hearing aid services via synchronous teleaudiology: Feasibility results from the conexiones randomized controlled trial. Ear and hearing, 44(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001281

Coco, L., Titlow, K. S., & Marrone, N. (2018). Geographic distribution of the hearing aid dispensing workforce: A teleaudiology planning assessment for Arizona. American journal of audiology, 27(3S), 462–473. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJA-IMIA3-18-0012

Findlen, U. M., Gerth, H., Zemba, A., Schuller, N., Guerra, G., Vaughan, C., ... & Benedict, J. (2024). Examining barriers to early hearing diagnosis. American journal of audiology, 33(2), 1-10.

Goulios, H., & Patuzzi, R. B. (2008). Audiology education and practice from an international perspective. International journal of audiology, 47(10), 647–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020802203322

Hixon, B., Chan, S., Adkins, M., Shinn, J.B., & Bush, M. (2016). Timing and impact of hearing healthcare in adult cochlear implant recipients: A rural-urban comparison. Otology & neurotology, 37(9). 1320-1324. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001197.

Jenstad, L., & Moon, J. (2011). Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to hearing aid uptake in older adults. Audiology research, 1(1), e25. https://doi.org/10.4081/audiores.2011.e25

Kenyon, C., Sandel, M., Silverstein, M., Shakir, A., Zuckerman, B. (2007). Revisiting the social history for child health. Pediatrics, 120(3):e734-738. PMID: 17766513. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-2495.

Knudsen, L.V., Oberg, M., Nielsen, C., Naylor, G., & Kramer, S.E. (2010). Factors influencing help seeking, hearing aid uptake, hearing aid use and satisfaction with hearing aids: a review of the literature. Trends in amplification, 14(3), 127–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084713810385712

Matiz, L. A., Leong, S., Peretz, P. J., Kuhlmey, M., Bernstein, S. A., Oliver, M. A., ... & Lalwani, A. K. (2022). Integrating community health workers into a community hearing health collaborative to understand the social determinants of health in children with hearing loss. Disability and health journal, 15(1), 101181.

Nicholson, N., Rhoades, E. A., & Glade, R. E. (2022). Analysis of health disparities in the screening and diagnosis of hearing loss: Early hearing detection and intervention hearing screening follow-up survey. American journal of audiology, 31(3), 764-788.

Nieman, C. L., Marrone, N., Szanton, S. L., Thorpe, R. J., Jr, & Lin, F. R. (2016). Racial/Ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in hearing health care among older Americans. Journal of aging and health, 28(1), 68–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315585505

Nieman, C.L., Tunkel, D.E., Boss, E.F. (2016). Do race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status affect why we place ear tubes in children? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 88, 98-103. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.06.029. PMID: 27497394; PMCID: PMC4988399.

Novilla, M.L.B., Goates, M.C., Leffler, T., Novilla, N.K.B., Wu, C.-Y., Dall, A., & Hansen, C. (2023). Integrating social care into healthcare: A review on applying the social determinants of health in clinical settings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public health, 20(19), 6873. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20196873

O'Brien, M., Danis, D. O., 3rd, Gall, E., Woods, K., & Noonan, K. (2024). Social determinants of health and hearing loss in U.S. adults. The Laryngoscope, 134(6), 2848–2856. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.31268

Citation

Coco, L. (2024). Social determinants of health and audiology. AudiologyOnline, Article 29108. Available at https://www.audiologyonline.com