This text course is an edited transcript of a live webinar that took place in August 2013. Download supplemental course materials.

Valerie Lebeaux: I am the Consumer Education and Rehab Manager at Advanced Bionics and will be your host for this course. Today’s presentation is Singing in the Rain: Using Music to Reinforce Listening and Spoken Language in Children with Hearing Loss. As you may have guessed by the title, water is our theme. Advanced Bionics is proud to have the Neptune Sound Processor - the world’s only waterproof sound processor - because it allows all children to be able to sing in the rain.

Our guest today is Christine Barton, an award-winning composer and performer, as well as a board-certified music therapist. In addition to her private practice, Chris is also a music consultant to Advanced Bionics and provides music therapy services to the children of St. Joseph Institute for the Deaf, located in Indianapolis. She primarily works with children with hearing loss and those with autism spectrum disorders. She is the composer and performer of the songs on the TuneUps CD. Chris is also a recipient of the 2009 Most Valuable Product Award by readers of TherapyTimes.com. She recently completed the University of North Carolina’s post graduate certificate in auditory learning in young children. She is a recent addition to the project ASPIRE team, headed by cochlear implant surgeon Dana Suskind at the University of Chicago.

TuneUps is a fun, musical resource. Advanced Bionics offers a variety of free musical resources in the Listening Room (www.TheListeningRoom.com). Chris Barton has been a major contributor to the development of these resources and has also collaborated with Amy Robbins to develop TuneUps. You can find some of the TuneUps activities for free in the Listening Room, and the full musical program is available for purchase. TuneUps seamlessly weaves music with spoken language to promote listening and spoken language development. Before we start, if you would like to learn more about cochlear implants and any other resources that Advanced Bionics provides to support children with hearing loss, you can visit our Web site (www.AdvancedBionics.com) or the Listening Room (www.TheListeningRoom.com) where you can find listening and language activities for children and adults with hearing loss. Log onto the www.HearingJourney.com, join Tools for Schools (www.AdvancedBionics.com/tfs), or contact the Bionic Ear Association at AdvancedBionics.com or (866) 844-HEAR. Now I would like to turn the microphone over to Chris Barton.

Chris Barton: Thank you, Valerie. As I was preparing this webinar, it occurred to me that the good thing about doing a music-based webinar is that you will be comfortable singing along, because no one can hear you!

As was mentioned, this particular webinar is called Singing in the Rain. All of the music experiences, songs, and movement ideas were written at the invitation of Advanced Bionics in honor of the premier of the Neptune immersible sound processor, which happened last year at the AG Bell conference. I was excited and honored to have been a part of that whole celebration.

I will touch on a number of different ideas today. First is the importance of the music and language connection. I will discuss some of the current research that exists on music and children with hearing loss who are engaged in a listening and spoken language approach, some music perception and production issues that children with cochlear implants (CIs) may face, and then I will provide you with several ideas and songs that you can use right away with your children or with your students.

Why Music and Language?

Music and language are the two traits that define us as being human. There must be something very special about them. We know that they share terminology. We can talk about both music and speech in terms of pitch, as well as timbre, which is the unique characteristic that defines a particular sound. Timbre is what allows us to be able to tell the difference between a man’s voice and a woman’s voice, or a flute and a guitar, or even a dog and a cat. Timbre is very critical in being able to discriminate between sounds. Then there is timing, which has to do with rhythm and tempo - how fast or how slow something may be. Jerry Seinfeld used to do funny skits about soft talkers and fast talkers, but timing is obviously involved in music as well.

Intensity refers to volume - how loud or how soft something may be. Speech and music both have melodic contour. We do not want to be monotones in the way that we speak or sing. Many of the processing mechanisms that are used to listen to music or language are engaged at the same time. Early exposure is critical in order to become fluent in both music and speech. This may be new to some of you, but both music and language follow a time-ordered sequence of skills or milestones. Children must go through a sequence of milestones to progress to the next language level, and the same is true of music.

There are differences between music and language as well. Music encompasses a greater spectral range. If you think about a piano, the very lowest notes and the very highest notes on the piano are way outside the spoken language range. Music can tap into all different ends of the spectrum that the human ear can hear. Music can exist without language. There are many wonderful pieces of instrumental music that are very important to us. Language can be altered in music without changing the music. Here is an example. If I were to sing the Hallelujah chorus by Handel, I would sing it, “Hallelujah! Hallelujah! Hallelujah!” I would never say, Hal-le-lu-jah or Ha-lle-lu-jah, but even if you did, it would not change the music. Within the music, we still get the meaning, and the music retains its musicality. We can alter the lyrics without doing any damage to the music itself.

Spoken language surrounds most children, whereas music may not. We do not know how many of our children with hearing loss are exposed to music. It would be understandable that parents and caregivers assume that because their child has a profound hearing loss, they will not get anything out of music. As we talk about guiding practice and working on language acquisition, we typically use the milestones of hearing children. The same is true when we talk about music development. We are going to look at how it happens in hearing children and then assume that it is going to be delayed in children with hearing loss. Music may be impacted, even more with some children who have CIs. The idea is that they follow through this progression in order to become fully musical at some point. I am not talking about professional musicians. I am talking about being able to sing a song correctly.

Music Development in Hearing Children

The first musical response that we see in babies is sensorimotor response. You may notice when you sing to a baby or if the baby hears music, the first thing they do is to start kicking the legs and moving the arms as fast as they can. This is one area of which I am always aware when working with young children with CIs. When I see them start to bop along to the music or rock in their chairs, this tells me that the child has discovered that music is something separate from spoken language. You will not get that kind of response when you are just talking with a child. That is one of the first markers that I like to look for.

Normal-hearing children between one and two years are starting to imitate some pitches and even begin to pick up on fragments of familiar songs. Two and three year olds sing while they are at play. This is a very normal part of childhood. They will incorporate what it is that they are doing in their play into these little bits and pieces of songs. Most of them are just made up, but some may have similarities to some familiar songs that they know. Then they attempt to learn the songs with the lyrics and the rhythms. By the time they are four and five years, they should be “beat competent,” which means they can march to a beat. They can pat their hands or their knees. They might be able do some rhythm sticks or something that would match up the beat of a particular piece of music.

Tonal center refers to a child’s ability to sing a song by starting off in a particular key and still end up in the same key. What is truly amazing is that by the time the child heads to kindergarten, he or she should be able to sing a song with the correct pitch, rhythm and lyrics. Guess what? No one has formally taught them that. They have picked it up through exposure and by engaging in the process of singing and listening to other children sing. It is very similar to the way that hearing children pick up language. If they have exposure to it and are engaged in it, they will pick it up almost effortlessly.

Music presents unique challenges for children with CIs. Some studies say that these children can perceive rhythm nearly as well as their hearing peers. Certainly, steady beat is something in which most of them can match and demonstrate competency. The majority, however, are less accurate than their hearing peers in being able to recognize songs. If I were to play the music to a familiar song that a child knows, a child with a CI may have difficulty recognizing the song without the lyrics. It is important to remember that a typical 4-year-old may have difficulty with that, too. There is a developmental hierarchy that needs to be in place. I do have a number of children that have had CIs from an early age who are quite good at recognizing songs; one of their favorite games to play is Name that Tune. I think early implantation and early intervention is critical at this point.

Pitch perception and production can be more of a challenge for CI users. If we think about cochlear implants as being developed to access speech, and we know that music is more complex than speech, then that would make sense. For some, music may not be as enjoyable. But my experience with young children is that it has been very motivating. I have very few children in my groups who could care less about music. Many of them are excited to come and participate. I also think we need to be aware that the majority of the research indicating that music is not enjoyable is completed on adults, particularly post-lingually deafened adults with CIs. Perhaps it is because they have a memory of the way that music “should sound,” and now it is very different. But for our young children who have never heard music except through a CI, perhaps it does not matter as much.

Why Should We Sing?

A handful of studies with individuals who have hearing loss have shown that music training has positive effects in cognitive, linguistic, memory and music perception domains (Abdi, Kahlessi, Khorsandi, & Gholami, 2001; Galvin, Fu, & Nogaki, 2007; Peterson, Mortenson, Gjedde, & Vuust, 2009; Yuba, Itoh, & Kaga, 2007). If you are curious, I encourage you to seek out these articles and read them. I think we should sing with our children who are deaf and hard of hearing. Daniel Ling was one of the pioneers in the spoken language approach at language acquisition in deaf and hard of hearing children. He was a firm believer that music needed to continue to be a very important part of their lives.

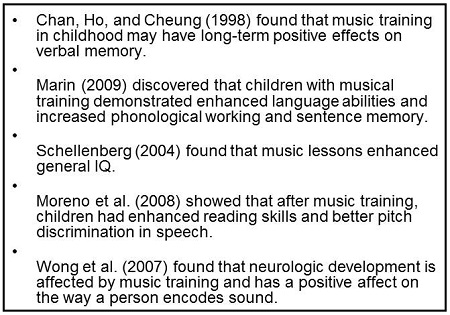

Other music training studies have been done on normal hearing individuals with favorable language and cognition outcomes (Figure 1). We understand much more about how music is processed by the brain and how it can affect other domains that we never imagined would be associated.

Figure 1. Music training studies and outcomes.

The main point I want you to take away from today is that your voice is the most important instrument you can own. You do not have to be a multi-instrumentalist. You do not have to be a major musician in order to utilize music with your child or with your students. I am serious about that. When we engage babies at the very beginning of life, mothers and fathers and caregivers alike use what we call “motherese” or infant-directed speech, or infant-directed singing. It is a sing-song way of speaking to the child. It is different. We do not talk to other adults in motherese, but we do engage babies in this. It engages their attention for one thing, and it conveys the emotional intent that the caregiver is trying to provide the child. Obviously, babies do not yet understand the words, but when you say, “Oh, you are such as sweet baby!” the child can understand the intent of your voice. It is interesting that many nursery songs and many of the first intervals that children sing incorporate this notion of motherese. We even have named it the “mMama interval,” which is a minor third in music terms. It is when the child says “Mama” or “Daddy” or “Mama, where are you?” It is almost a sung in a phrase.

Mother Goose realized that it was important a long time ago when the rhyme was coined, “Rain, rain, go away, come again another day. Little Johnnie wants to play.” If you were using this with your own child, you would substitute their name. Children love to have their names sung to them. It is very special and personal. Another one is, “It’s raining. It’s pouring. The old man is snoring. He bumped his head and went to bed, and couldn’t get up in the morning.” This, again, utilizes the tone and rhythm, “la-la, la-la-laaa.” If Mother Goose were around today, she would probably have to include the “nana-nana-boo-boo, you can’t catch me,” because that is the modern adaptation of the “mama interval.”

Pitter Pat

Now I would like to introduce you to the first song. This is a piece that I wrote for Advanced Bionics, but I use it all the time in therapy. I will play a little bit of it for you first, so you can get a feel for the song, and then I am going to show you some ways that you can adapt this and use it with your own children. This is Pitter Pat.

That gives you an idea of what the Pitter Pat song sounds like. Here is a way that you can use it without playing a keyboard or the drums or the cabasa. You can just sing it. If you have a child in a therapy session or your own child, I would substitute the child’s name first. If your child’s name is Hayley, I might sing, “It rained on Hayley and Hayley got wet. Pitter-patter, pitter-patter, pitter-patter pat.” I want you to sing along with me. This time, we are going to rain on Carolyn. “It rained on Carolyn and Carolyn got wet. Pitter-patter, pitter-patter, pitter-patter pat.” Now let’s have it rain on Brian. “It rained on Brian and Brian got wet. Pitter-patter, pitter-patter, pitter-patter pat.” Let’s have it rain on Jennifer. “It rained on Jennifer and Jennifer got wet. Pitter-patter, pitter-patter, pitter-patter pat.” You can incorporate the names of your family or children at school, and then you can branch out into some other categories, which is good for increasing vocabulary.

For instance, you could do animals. “It rained on the kitty and the kitty got wet,” et cetera. You can do food. “It rained on the pizza and the pizza got wet,” and have the child come up with the food that they want to see get wet. I have one little boy who is entranced with vehicles, so we had to do, “It rained on the truck and the truck got wet. Pitter-patter, pitter-patter, pitter-patter pat.” You can take this in any way and adapt it to whatever vocabulary on which you might be working. It is a fun thing to say, and it is very repetitive and rhythmic. I hope you have some good uses for this particular song. Please let me know if you come up with some great ideas. I would love to hear them.

It Rained a Mist

If you have access to either a floor drum or a drum that you could set on the table, you can do this next song called It Rained a Mist. You can all sit around the drum, take your fingers and gently wiggle them so they are just touching the drum head. It will sound a little bit like raindrops. If you do it gently, then you can sing over the top of it and the song goes like this. “It rained a mist. It rained a mist. It rained all over the town, town, town. It rained a mist, it rained a mist. It rained all over the town, town, town.” If you have an older child, you can explain what a mist is. That is not a vocabulary word that a lot of young children know, but this is a perfect opportunity to bring that to their attention. You have all been pitter pattering on the drum head.

Now you take your fingernails and swish them around the top of the drum. At the same time, you sing. “The wind did blow. The wind did blow. It blew all over the town, town, town. The wind did blow. The wind did blow. It blew all over the town, town, ____.” I am hoping you filled in that last word. That is a technique that I use with children. I leave off the last word of a familiar song, give them an expectant look, and they will give you something. It might not be the correct word, but they might give you something.

Then everyone starts really pounding on the drum, but not too loud at first. You still want to hear the singing. Sing it with me. “The thunder rolled. The thunder rolled. It rolled all over the town, town, town. The thunder rolled. The thunder rolled. It rolled all over the town, town, town.” I have a drum at St. Joe’s that is called a gathering drum. It is about four feet around. I can put 8 to 10 little children around it. Sometimes we will sit a child right on the drum and they can feel it through their whole being.

I think it is important to experiment with using different character voices and different ranges that we have in our voice. One reason is to help encourage this prosody. We do not want to turn out a bunch of monotone singers or speakers. By practicing using our voices expressively, it gives children awareness of all of the possibilities that they can do with their voices. Some children who have never done that only think that they have access to the voice that they use when they are speaking. In order to sing, we do not use a speaking voice; we use a singing voice. By getting way up high and way down low, children can understand that they have access to those ranges and can use them.

Itsy Bitsy Spider

An idea to incorporate this notion is to use a familiar song like the Itsy Bitsy Spider. I have three different sized spider puppets: small, medium and large. You sing the song in the voice that matches the size of the toy. I would start with the medium puppet, and we would sing it as usual. Then I would introduce the tiny spider and say, “I found a teeny-tiny spider, and we are going to sing it in our teeny-tiny spider voices. Are you ready? Let’s go!” Then I would bring out my very large spider and say, “I found a great big spider in my basement. It was hiding behind my dryer. If we were going to sing like a great big spider, we would sing, ‘The great big spider went up the water sprout.’” Children love this and think this is the funniest thing that they have ever seen.

After you have practiced this a few times singing in high, medium, and very low voices, hide the puppets behind your back and pull them out one at a time. Whatever the size of the spider that you pull out is the voice in which they have to sing. When they get adept at this, you do not even have to use one puppet for the entire song; you can switch it up. You might start with the medium spider, then switch to the teeny-tiny spider, and finish with the great big spider. You go back and forth between those different voices. This gives them practice in utilizing the whole range that they have.

Ken Bruscia is one of the luminaries in the music therapy field. He has done important work to try to get music therapy defined and specific. One of the terms Bruscia (1998) has defined is “referential improvisation.” Improvisation is music that is great in the moment versus music that is already pre-composed, like Twinkle-Twinkle Little Star. It is something that you are going to create in the moment, and the meaning of that particular music or process is formed around an image, story, event or even a feeling. You could choose a theme with which your child has some experience. For instance, if a child heard that Johnny’s birthday was coming, because they have been to birthday parties before and have had birthday parties themselves, they know what that means. They know that there will be children there. They will play games; there will be presents. There will be cake and candles, and they will sing Happy Birthday. They have a schema already. The same thing is true for a rainstorm, vacation, first day of school, et cetera. They know the different components that make up each of those events.

Make a Rainstorm

We are going to make a rainstorm. You could do this using body percussion if you do not have the instruments that I am going to introduce here. You can use your feet to stomp. You can use your hands. You can use fingers to tap to make light little rain. You can make your voices to make the sound of wind blowing. One instrument that I often use when we create a rainstorm is a rainstick. If you turn it over, little beads will fall down through the tube and make the sound of gentle rain. It is a lovely and soothing sound. A floor drum would be a great drum to use for thunder. I also highly recommend a thunder tube. They are available through West Music (www.westmusic.com). The idea is that you have a hollow tube with a very long spring attached. When you wiggle the tube gently, the spring vibrates and it sends a very low sound up through the tube, and it sounds exactly like thunder. The children love it. It is interesting that many of the children that I see, probably because they are very young, are often afraid of loud sounds that they do not control, but if you give them the chance to do the thunder tube or to play a drum or crash a cymbal, they are very enthusiastic. I think it has to do with control.

The children came up with the idea to have a rainbow at the end of our rainstorm. I have some little hoops that have five or six different streamers the colors of the rainbow on them. We call them Rainbow Rings. At the end of our rainstorm, then we get out the rainbow rings and we sing a song about the rainbow.

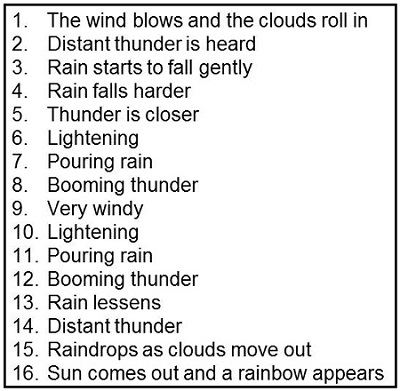

Here is a possible sequence that you could use to create a rainstorm (Figure 2). You would hand out the instruments to the children, and each child would have a part to play. For children who are older and can read, you do not need to say anything; they can just play. However, for younger children, you would narrate the story and have them play their part as their part appears in the sequence. To deepen this experience, I have turned on occasion to the Visualizing and Verbalizing approach that Nanci Bell has created for Lindamood Bell curriculum (www.LindamoodBell.com). It is a wonderful program that helps children create images, and those images then become the basis for their language comprehension and higher levels of thinking. One part of that program that I like use are the structure words (i.e., size, color, number, shape, where, mood, background, when). Once you decide on the topic that you want to improvise, the structure words can help deepen that idea. How big is this particular event or thing, like the rainstorm? What color does it have?

Figure 2. Rainstorm sequence.

A favorite improvisation that I do later in the Fall is taking a trip to a haunted house. All my children love this. If we are using the structure words to help shape how we are going to develop the sequence, we are going to talk about what it is. It is a haunted house. What does it look like? Is it big? Is it small? Are there colors? Is it black or red? What color do you think it is going to be? Is there one house? Are there two houses? What are the shapes of the houses? What do you think you might find when you get to the haunted house? What could be in a haunted house? Then we would develop the sequence. “How are we going to get to the haunted house? We are going to walk through the woods. What would it sound like?” We would make the footsteps. “Would we hear anything when we are in the woods? We might hear some owls. Who has a good owl sound? There could be some thunder. It could be a rainy night. We get to the door. We could knock on the door and we could open the creaky door.” It provides an opportunity to explore sound in a way that if you did not have the structure of this referential improvisation, it may not take shape as this.

Then, after we have developed the whole story and we have practiced and played all the instruments, I typically record it with my older students. There is no narration, but if someone were to listen to it, they could tell it sounds spooky. It sounds like they are going to a haunted house. I call these sound stories.

Tightrope Walking in the Rain

A favorite movement activity is what I call Tightrope Walking in the Rain. I put down a piece of masking tape, perhaps 10 or 12 feet long. If you are outside, you can use sidewalk chalk. I find a piece of instrumental circus music. We talk about what a tightrope is. Some children may have never been to the circus and do not know what a tightrope is. You need to impress upon them that this is something that they would be doing way up high, and they have to be very careful not to fall. I would give them an umbrella, and they hold the umbrella in one hand and balance with the other. We would have them first walk forward, one foot in front of the other, on the tape. Then, perhaps we would have them walk backwards, tiptoe, or sideways. As they become more adept at this, change the tempo of the music, so that sometimes they may need to go across quickly and other times the need to go more slowly. They will match the way that they move across the tightrope in relation to the music that they hear.

My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean

I also use instruments called ocean drums. They are similar to rain sticks in that they have little beads on the inside. They make large ones and smaller ones for toddlers. If I am working one-on-one with a child and a parent, I would have the three of us hold on to the drum and move it as we sing the song My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean, but then I would substitute the name of the child. If I have a group, I would put a child or even two children in the middle of a big blue scarf with the ocean drum. They are responsible for playing the ocean drum, and the other children move the scarf up and down like waves in the ocean as they sing. One of the things I show them early on is that when we sing the verse, they roll the ocean drum very softly and quietly. But when we get to the chorus, if they tip the drum from side to side, it will make a much more succinct sound and go right in time to the music. That gives me the opportunity to note if the children are hearing the differences between the way we sing the verse and the way we sing the chorus.

Slippery Fish

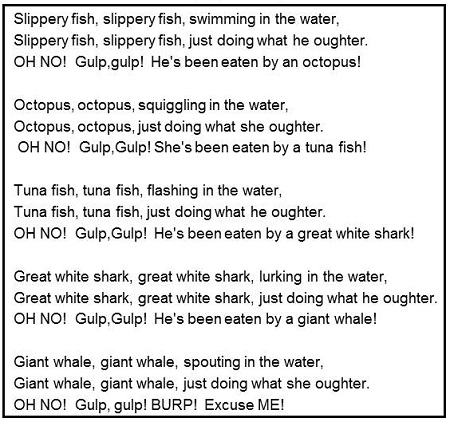

I am going to share Slippery Fish with you (Figure 3), but before I do, I would like to teach you the hand motions. This is a good experience for you, because this is what your children are learning when we talk about the listening and spoken language approach. I am doing this only through audition. You do not get any visual cues here.

Figure 3. Slippery Fish lyrics.

With the first verse, “Slippery fish, slippery fish, swimming in the water,” you are going to put your hands together and you are going to move both hands as if you were a little fish swimming in the water. For the octopus, you are going to lock your thumbs together and wiggle your fingers. If you have your two thumbs locked upward, you have eight fingers or “tentacles” that can wiggle. For the tuna fish, put the base of your palms together and open up your hands. Curl your fingers in so that they look like teeth and you snap them open and shut, open and shut. For the great white shark, put your hands together and stick your thumbs straight up in the air so that they become the fin of the great white shark. Then for the giant whale, open up your hands as large as you can and do big claps. I am going to play the song in its entirety because the best part is at the end. At least that is what the children will tell you. Get your hands ready.

I am hoping that you all were using your hands to sing along with the Slippery Fish song. It is interesting that even the littlest, most inexperienced children can recognize when we come to the “Oh no!” and we put our hands on our heads, and then at “Gulp, Gulp,” we pat our tummy. They all get it, and they anticipate when that is going to happen. Of course, the burp is their favorite part.

Resources

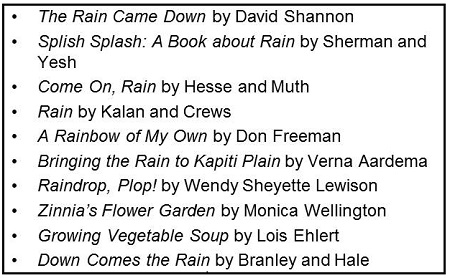

I have provided a few of my favorite books (Figure 4) when it comes to rain, as well as a link to Vanderbilt University’s Children’s Hospital which has a very nice Bringing the Rain to Kapiti Plain video (https://teacherlink.ed.usu.edu/tlresources/units/byrnes-literature/SECurtis.html

https://www.childrenshospital.vanderbilt.org/uploads/documents/bfb_ras_bringing_the_rain_to_kapiti_plain.pdf). It is in a book form.

Other online resources include www.TheListeningRoom.com, www.westmusic.com, and www.lindamoodbell.com. I like West Music because they have a lot of instruments that are appropriate for very young children, yet they sound nice. A lot of times instruments for young children are just toys. They do not have any discriminating or pleasing sound to them at all. I am a firm believer that even though there are instruments provided for young children, they should still have an authentic, musical sound to them.

Figure 4. Resource books for rain activities.

Another resource is the Lindamood Bell Learning Centers (www.LindaMoodBell.com). I encourage you to check out any of the resources included in this presentation. Visit my home page (www.christinebarton.net) as I have a number of songs that I have written and turned into books so the child can watch the book proceed and listen to the song at the same time. They do not have to turn the page; the pages turn all by themselves. Additionally, several research articles pertaining to music and cochlear implants are listed in the References section for your review.

Questions and Answers

When using music with a child who might be more auditorily sensitive, do you have any strategies that we could use to make music fun and enjoyable?

That is a good question. Certainly some children are very sensitive to certain sounds. However, as I mentioned earlier, if I introduce a new instrument to a child who has autism and hearing loss, sometimes they are reluctant because I think they have been unpleasantly surprised by unexpected sounds in the past. If I introduce it and show it to them first and then let them play it, which means that they have the control over the volume and how it is going to be played, then I usually do not have a problem with heightened sensitivities. It is one of those situations where you have to use trial and error and figure out which sounds the children gravitate to and which sounds are not appreciated.

A comment we often hear from parents is, “I would love to start music with my child, but where do you start when they are at the very beginning stages of learning to listen?” Do you have any suggestions for our parents?

Yes I do. I think that the Mother Goose rhymes and the finger plays that we used to sing all the time to children are the place to start. At first, I would pair a finger movement with a song, such as Itsy Bitsy Spider, because the child does not have the ability to sing yet. If they start doing the movements along with the singing, then ultimately they have the ability to request the song by just starting with a particular movement. It is a great way for them to communicate their wants. When a parent starts to sing a particular song from the child’s repertoire of three or four finger plays that they know, observe whether or not the child matches the correct movements or finger movements to that piece. If you go to www.TheListeningRoom.com and log into the Infants and Toddlers site, there are various music activities available for you that I have written, prepared, and collected that you can download to use with the itsies: the children and toddlers who have cochlear implants.

Since there are no more questions, let’s close with the song Grandpa Says.

This is a piece that I wrote in honor of my grandfather. I do not have many memories of him, but the one that really stands out was the summer when I was about nine years old. We were visiting my grandparents who lived in Chicago. It was a very hot summer night. Grandpa and I decided we were going to sleep outside on the sleeping porch, which was a very common thing to do before anyone had air conditioning. You would sleep out on the porch because it was too hot to sleep in the house at night. A storm rolled on through and I got scared. I climbed into my grandpa’s lap. He said, “You know, when you hear the thunder it is a good thing because you know you haven’t been struck by lightning.” That is the memory I carry of my Grandpa, and here is the piece that I wrote for him.

References

Abdi, S., Khalessi, M. H., Khorsandi, M., & Gholami, B. (2001). Introducing music as a means of habilitation for children with cochlear implants. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 59, 105-113.

Bruscia, K. E. (1998). Defining music therapy (2nd ed.). Gilsum, NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Chen, J. K., Chuang, A. Y., McMahon, C., Hsieh, J. C., Tung, T., & Li, L. P. (2010). Music training improves pitch perception in prelingually deafened children with cochlear implants. Pediatrics, 125(4), 793–800.

Galvin, J. J., Fu, Q. J., & Nogaki, G. (2007). Melodic contour identification by cochlear implant listeners. Ear and Hearing, 28, 302–319.

Gfeller, K. (2000). Accommodating children who use cochlear implants in music therapy or educational settings. Music Therapy Perspectives, 18, 122–130.

Marin, M. M. (2009). Effects of early musical training on musical and linguistic syntactic abilities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1169, 187-190.

Moreno, S., Marques, C., Santos, A., Santos, M., Castro, S. L., & Besson, M. (2008). Musical training influences linguistic abilities in 8-year-old children: More evidence for brain plasticity. Cerebral Cortex, 19(3), 712-23.

Peterson, B., Mortenson, M. V., Gjedde, A., & Vuust, P. (2009). Reestablishing speech understanding through musical ear training after cochlear implantation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1169, 437–440.

Schellenberg, E. G. (2004). Music lessons enhance IQ. American Psychological Society, 15(8), 511-514.

Stordhal, J. (2002). Song recognition and appraisal: A comparison of children who use cochlear implants and normally hearing children. Journal of Music Therapy, 39(1), 2–19.

Yuba, T., Itoh, T., & Kaga, K. (2007). Unique technological voice method (the YUBA method) shows clear improvement in patients with cochlear implants in singing. Journal of Voice, 23(1), 119–124.

Wong, P. C., Skoe, E., Russo, N. M., Dees, T., & Kraus, N. (2007). Musical experience shapes human brainstem encoding of linguistic pitch patterns. Nature Neuroscience, 10, 420-422.

Cite this content as:

Barton, C. (2014, January). Singing in the rain: using music to reinforce listening and spoken language in children with hearing loss (for professionals). AudiologyOnline, Article 12371. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com