Learning Objectives

- After this course learners will be able to list several speech-in-noise tests that can be used in the clinic.

- After this course learners will be able to describe how to score and interpret several speech-in-noise tests.

- After this course learners will be able to describe how to use the results of speech-in-noise tests for patient counseling.

Introduction

Let's start off today’s course by comparing what we do in audiology to the field of optometry. Optometry has some similarities relative to audiology, and some dissimilarities, which I want to focus on for now. If someone walks into an optometrist’s office with the complaint of trouble seeing at a distance, the optometrist would have the person read the Snellen eye chart at a distance of twenty feet. Makes sense, right?

What if the patient’s main problem was reading magazines and newspapers? If you’re over the age of 40, you may be starting to have trouble reading from that distance and know exactly what I mean. In this case, the optometrist would have the patient read off a card with different sizes of print at arm's length. This also makes sense. What if the complaint were having trouble differentiating colors? The optometrist would then conduct a standardized test of color differentiation. There are ten different cards that they use for this standardized test. It’s all pretty clear—you do a test related to the complaint.

Now, let's take the typical patient who comes in to an audiologist's office with the complaint of having trouble understanding speech in background noise. If the person is a potential new hearing aid user, that will likely be the complaint in 90% or more of the cases. What does the average audiologist do? Well, most will assess speech understanding in quiet. Isn’t it a bit strange that people walk in with one problem and we do a test for something totally different?

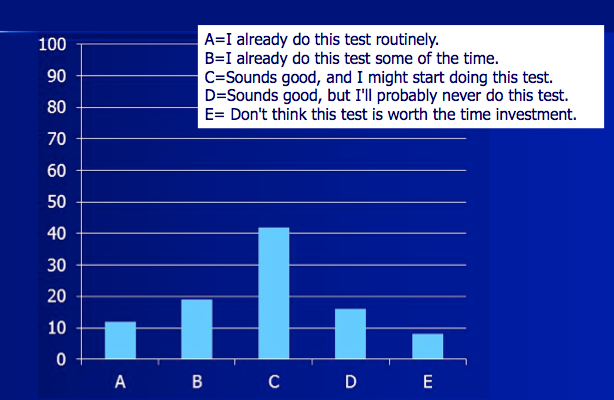

In 2010, I conducted a survey at two audiology professional meetings, of 107 audiologists who routinely fit hearing aids. The purpose of the survey was to look at audiologists’ use of speech-in-noise testing in their clinical practice. This survey was given after I had conducted a talk on different speech-in-noise tests, so everyone who took the survey was familiar with the speech-in-noise tests that were listed in the survey.

We asked about use of the QUICK-SIN (Killion, Niquette, Gudmundsen, Revit, & Banerjee, 2004) and other popular speech-in-noise tests. Keep in mind that people tend to exaggerate on these kind of surveys; they may say they're doing things more often than really true. The most commonly used test was the QuickSIN, but only 10% of audiologists reported doing this test routinely (Figure 1). Twenty percent reported doing the test some of the time. About 40% reported that “I might start doing the test”. The rest indicated that they will “Probably never do the test” nor did they think that conducting the QUICK-SIN was “worth the investment”.

Figure 1. Survey regarding use of the QuickSIN (n = 107 audiologists who routinely fit hearing aids).

Audiology Today Article

Last year, there was an article in Audiology Today, written by George Lindley on this same topic (Lindley, 2015). The article was entitled, They Say “I Can't Hear in Noise,” We Say, “Say the Word Base.” George indicated that in his practice, he gives the QuickSIN to everyone. He gives three reasons for this. First, he suggested you could do the test unaided at a conversational level to get a general idea of how the patient is performing in the real world. He suggested that you could then do the unaided QuickSIN at a loud level under earphones, which is the recommended method for presenting the test. This way you’re maximizing audibility to see how well the patient could possibly do. Then, he suggested doing the test aided at an average speech level. He suggested doing a manufacturer’s first fit on a pair of high quality hearing aids, fitting the person with these hearing aids just to get an idea of how they might do if they were aided. He cited the Walden and Walden (2004) research that found a 1.7 dB benefit in the aided condition, as compared to the loud unaided condition under earphones—in other words, aided should be equal to or slightly better than the best earphone score.

He also did a small clinical study, where he tested 48 patients in his clinic who were being considered for hearing aid fittings. He used the aided testing approach just described, at an average speech level. He found that 40% had normal or near normal performance in noise, while the rest had mild (33%), moderate (22%), and severe (4%) impairments relative to their performance in background noise. In other words, about 60% were not performing normally with speech understanding in background noise. He then did a regression analysis and found that factors such as age, their word recognition score in quiet, and their hearing loss only accounted for about 54% of the variance of the QuickSIN score. In other words, his point in this article was that the QuickSIN performance can’t be predicted very well using other factors. He concluded that you could use the QuickSIN for patient counseling, to help decide the level of technology to fit them with, and whether the person may need assistive devices, such as remote microphones.

A few months later, there was a letter to the editor in the Nov/Dec 2015 issue of Audiology Today from John Tecca about Lindley's article. The points made by Tecca were that the QuickSIN really may not be representative of every day function, and it may not effectively predict real-world satisfaction with hearing aids. He went on to state that there really is little evidence which concludes that clinical tests of speech-in-noise are a good predictor of how people will do in the real world. He also didn't think it was a great idea to test people with hearing aids that were not fitted precisely (i.e. Lindley’s approach of using the manufacturer’s First Fit) just to obtain a QuickSIN score. He added, that there are so many factors that go into the decision of what technology should be fitted, that maybe it's really not worth your time to do a QuickSIN test. Basically, he was questioning George's thoughts about why we should even do speech-in-noise testing. He made some good points, and questioned not only Lindley’s recommendations, but what we have heard for years from leading experts regarding the clinical use of speech-in-noise testing (for review see Wilson and McArdle, 2008).

To help make this all even more fun reading, Lindley then replied to Tecca. He pointed out that he isn’t really doing the speech-in-noise testing to predict how the patient would perform in the real world; he is simply doing the testing to see how they compared to people with normal hearing. He also pointed out that much of what is listed in best practice statements is only supported by minimal research evidence, and that some things we do because we believe it is the right thing based on our clinical knowledge and experience. There may be some studies that say, yes, it's a good thing, but indeed, there may be not as much evidence as we would like for some of the things we do in practice.

I encourage you to read the article as well as the Tecca and Lindley responses. I tend to side with George on that controversy, although, I think John Tecca made some good points.

WIN Test

One of the things that convinced me about the importance of speech-in-noise testing was the work by Richard Wilson, which I'd like to review with you. Richard developed the WIN (Words-in-Noise) test (Wilson, Carnell, & Cleghorn, 2007). It's an excellent test that hasn't gained the popularity it deserves. Let me give you just a little background.

The test material is the NU-6 list, using a female talker. It’s on a CD widely distributed throughout the VA. Richard Wilson was a researcher with the VA for many years. The background noise is multitalker babble. The test consists of five words at seven different babble levels, going from 0 to 24 dB in 4 dB increments. The score is the SRT-50 or the point where people are getting 50% correct.

General interpretation guidelines for the WIN are as follows:

- Normal: </= 6 dB

- Mild: 6.8 – 10.0

- Moderate: 10.8 – 14.8

- Severe: 15.6 – 19.6

- Profound: >20 dB

I’ve already mentioned the QuickSIN—Wilson conducted two different studies comparing the WIN to the QuickSIN, and found that the results are pretty similar between the two tests.

Here is what I consider to be the most important about all this. We know that most audiologists do not do speech-in-noise testing and tend to use monosyllables in quiet. Wilson (2011) did a study comparing the results of the WIN to NU-6 testing in quiet, using a very impressive sample size of hearing impaired individuals—3,430 subjects! What he found:

- That 70% of patients had NU-6 performance in quiet that was good or excellent, but only 6.9% of these same patients had normal scores on the WIN. In other words, if you looked at a patient’s score of 92% on monosyllables in quiet and thought to yourself, "Ah, this guy's doing 92% - that's excellent", the probability of that person doing well in background noise is very unlikely.

- Only 6% of the 3,430 patients had normal performance for the WIN. Of those who were normal on the WIN, 98.5% were normal for words in quiet. Therefore, the WIN is very good at predicting who is going to do well in quiet.

- Finally, of the over 3,000 patients who had abnormal performance on the WIN, 46% of them had scores on NU-6 of 92% or better, going back to our first point.

If you only had time for one of these tests, what would provide the most information? It seems to me that the test you would want to do is the WIN because it is very highly predictive of the NU-6, but the NU-6 doesn't predict how people do in background noise. Interestingly enough, in clinics everywhere, people do just the opposite. They do a test that has no predictive value – monosyllables in quiet - rather than a test that does have predictive value. Although speech-in-quiet testing and speech-in-noise testing are similar, they’re really looking at two different things. If you're fitting hearing aids, I think it's important to know how your patients are going to perform in background noise.

Six Reasons for Speech-in-Noise Testing

In case you are not yet convinced to start doing speech-in-noise testing routinely in your practice, let me give you six reasons why I think you would want to add this testing to your clinical protocol.

Reason #1: To Address the Patient’s Complaints

As in the optometrist example, speech-in-noise testing is a way to show the patient that, yes, I understand your problem and, therefore, I'm going to do a test related to why you came to see me in the first place. It helps to foster the professional-patient relationship; it shows that you are listening and you understand their reason for the visit.

Reason #2: Results from Speech-in-Noise Testing Will Help you Select the Best Technology

When the QuickSIN was first introduced, I think Mead Killion suggested that it might help determine who really needs directional technology and who doesn't. Today, most everyone is fitted with directional technology, and even basic instruments usually have directional technology, so this logic doesn’t really apply anymore. It will, however, help you to address some other special needs, such as the need for remote microphones. It also may help you make decisions for a unilateral versus a bilateral fitting, or what ear to fit when the patient only wants to purchase one hearing aid. Perhaps, it may even help you decide when to fit a BiCROS if you see that the score is so bad in one ear that the patient may not obtain much benefit if that ear were aided. I believe the results will help with technology decisions such as these, as I will show you with a few case studies later in the presentation.

Reason #3: To Establish a Baseline for Measuring Aided Benefit

By doing a baseline QuickSIN measure, you can later determine the benefits of hearing aids, and demonstrate to the patient that hearing aids indeed work in background noise.

Reason #4: To Monitor Performance Over Time, Such as Year Over Year

When you've conducted a very reliable, controlled test you can then monitor changes over time. Remember, as we just discussed with the WIN test, these tests do not correlate with speech-in-quiet tests. If you monitor a person over time by their speech recognition in quiet, you may not know if their speech recognition in noise performance is going down.

Reason #5: To Assist with Counseling

Now, you have a test that can help you discuss with the patient how they might do in various situations. It will very easily explain why they're having trouble in certain listening situations and you have that information in front of you. If you do aided testing, which is yet another use of these tests, you now will be able to give them realistic expectations for different types of listening situatioins.

Reason #6: To Help Patients Make a Decision

Speech-in-noise testing can help patients who are not sure whether or not hearing aids are going to help them. You can sit them in the sound field and do a very quick unaided versus aided speech-in-noise test. The results can give them the confidence that yes, hearing aids really do work and, in fact, they just did better in background noise during this testing, which is the very problem that they reported when they came in. In this case, you should use a relatively soft input level to demonstrate the benefits of audibility. If you use a louder presentation level, and they have only a mild-to-moderate hearing loss, there may not be any difference, aided or unaided.

And a bonus reason: MarkeTrak VIII revealed that when you do speech testing as part of the hearing aid fitting, patient satisfaction and patient loyalty improve. We are not really sure why, as that wasn't specifically asked as part of the survey. It could simply be that the act of doing speech testing gives the patient confidence that the hearing aids are working. Or, knowing the patient’s speech understanding in background prompted the dispensing audiologist to be a better counselor.

Considerations for Choosing a Test

If you're now convinced that you might start doing speech-in-noise testing routinely, you have to decide which test to use. There are probably 10 different tests available, and I'm going to talk about five of them today.

Here is your easiest decision of what not to do, which unfortunately some people are doing. Do not take the NU-6 list or the W-22s and then add in some background noise. That doesn't work, it's not reliable, and you will have few or no norms. There are much, much better ways to do this testing, so do not use this approach.

Here is what you want to consider. You want an approach that's well researched; one that has peer-reviewed articles behind it showing what the norms are, what the critical differences are, and so on. You want a test that is reliable, meaning it has good test, retest reliability. You want a test that is good at separating normal from abnormal, because that's why you're doing the test in the first place. You want a test that can be used with a wide range of patients. You don't want it to be too easy or too hard. Most of you are busy, so you also want a test that's easy to administer and score, so that there is minimal time investment. I know that some of you work in a busy ENT practice, and sometimes you may only have a half an hour to see a patient. There are good speech-in-noise tests that only take 5 minutes to administer, but I still hear professionals say, “Do I really have time to add this extra 5 minutes?” In most clinics, you can find 5 minutes, but you want something that only takes 5 minutes, not something that may take 20 minutes.

Five Choices for Speech-in-Noise Tests

Most tests use an adaptive signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), while some used a fixed SNR. An adaptive signal-to-noise ratio means that you test at different signal-to-noise ratios and the score you end up with is an SNR. If the score was 4 dB, this means that at a +4 dB SNR, the person got 50% correct. I will discuss more about adaptive versus fixed SNR later.

Here are five reasonable choices: the Hearing-in-Noise Test (HINT; Nillson, Soli, & Sullivan, 1994), the QuickSIN, the BKB-SIN (Etymotic Research, 2005), and the WIN, all of which use an adaptive SNR; and the Connected Speech Test (CST; Cox, Alexander, & Gilmore, 1987), which uses a fixed SNR.

The HINT is very popular among researchers, but not popular at all among clinicians. The QuickSIN, which we talked about earlier, is the most popular speech-in-noise test among clinicians. The BKB-SIN has been around now for almost 10 years, although I don't see it being used a lot. The reliability is as good as, and may be better, than the QuickSIN. The vocabulary in the sentences is easier than the QuickSIN, and it has been normed down to about the age of 5 or 6. If you had to pick one for the pediatric population, it would be the BKB-SIN.

The Connected Speech Test (CST) from Robyn Cox uses a fixed SNR, as I mentioned. When you do a fixed SNR, then you score in percent correct. You can take a test like the QuickSIN and also score it in percent correct, it just isn't the standardized way of doing it. I will go into that later.

Sentences v. Words

The other question you have to ask is do I use sentences or words? Rachel McArdle and Richard Wilson (2008) wrote a good review article on selecting speech-in-noise tests. In that article, they discussed the following advantages of using sentences. They indicated that sentences have better face validity; they are similar to what the patient experiences in everyday listening. They are probably a better approximation of how a person understands conversational speech, as monosyllables have a lack of lexical, semantic and syntactic redundancies. Sentences provide context which helps with guessing the individual words, which is what we often do when we are listening in noise.

McArdle and Wilson, however, also discussed the advantages of using single words. The syntax and structure of a sentence will sometimes pretty much give away the answer. You are not really testing speech understanding in noise if they can predict the words. For example, a sentence on the HINT is, “The fire was very ...”. You could likely figure out that the last word is “hot”, as could most of your patients. They don't really have to hear the word “hot” or understand it; they could get that item right simply by filling in the blank from the contextual cues.

Wilson and McArdle also point out that sentences are going to involve a little more working memory, and so older patients might have more trouble with a sentence test. They believed that these reasons were strong enough to only use single syllable words. Most of the tests, however, do use sentences, although you score them for individual words. The exception is the HINT, where you have to get the entire sentence correct to count the test item as correct.

Types of Noise

There are many choices for background noise stimuli, including speech-shaped noise, which is used with the HINT; and multitalker babble, which is used with the CST and the WIN and provides a real-world component. This would be what you might hear if you were at a cocktail party or a noisy restaurant. A somewhat unique noise signal, four-talker babble, is used for the QuickSIN and the BKB-SIN. Because there's only four talkers in this noise, when you are at the +5 dB or 0 dB SNR, you actually can start picking up words from the four-talker babble.

When we're using noise as a masking signal, there's something called informational masking. This means, that not only is the noise energy itself doing the masking, but there is information in the masking that can have an effect on the listener. This is the case with four-talker babble. Informational masking could be good or bad, depending on what you are looking for in the testing. When you're conducting the QuickSIN, there are times when the patient will start trying to repeat back the words from the background talkers rather than the words in the target speech signal. You of course wouldn’t have this problem with a babble noise. Is this a bad thing? The fact is, when they're out at a restaurant or a party, they could be experiencing that very same thing, so you could argue that that gives the test more real-world face validity.

Adaptive versus Fixed SNR

Let's talk for a moment about using an adaptive versus fixed SNR. Here is a summary from a book chapter that I co-wrote with Todd Ricketts and Ruth Bentler (Mueller, Ricketts, & Bentler, 2013).

Advantages of using and adaptive SNR:

- You avoid a floor or ceiling effect (the patient scoring nearly all correct or all incorrect) because you will find the place where the person scores 50% correct.

- You can find the 50% correct point quickly and reliably – as compared to using a lengthy word list and scoring it in percent correct.

- Because the 50% point is at the steepest part of the person's articulation function, you can find significant differences, either between hearing aids or between the right and left ears of a patient. This is why the HINT is so popular with researchers; they could probably find a significant 1 dB difference between technology if the have enough subjects. However, if you're doing a word recognition test scored in percent correct, it may not turn out to be significant because you won’t be at that sweet spot of the articulation function.

Advantages of a fixed SNR:

- With a fixed SNR, you can simulate all kinds of different listening situations, which you easily can do with a test such as the CST. You can vary the SNR and make it really easy or very difficult.

- It's much easier to deliver the results to the patient (and to third parties) because you are explaining percent correct rather than a dB level in SNR. It's easier for the patient to understand their performance, particularly if you're doing unaided versus aided testing. For example, let’s say you do unaided testing and they score 30%. Then, you put a pair of hearing aids on them, repeat the testing, and they score 80%. The patient knows that they did a lot better, and you can tell them that they did 50% better. Compare that to a test in SNR, where you are always looking for the 50% correct point. The patient always thinks they're not doing very well as they are only getting half right. They don't really understand that the purpose of the test is that they're only going to get about half correct. Telling the patient that his SNR is 5 dB better is not very meaningful.

- Another advantage of a fixed SNR test is that the administration and scoring often is easier than an adaptive speech test. Some of the adaptive speech tests, like the HINT, for example, are a little tricky to administer if you don't have it computerized, sometimes having to use both hands simulataneiously!

Presentation Level

Finally, you need to decide on a presentation level. The way I see it, you really have three choices: a relative high level (the patient’s “Loud, But Okay” level), the level of average speech, and a softer than average speech level. Different levels for different questions that may need answering.

Generally these tests are conducted under earphones for ear-specific results. In this case, you would choose a high presentation level if you want to maximize audibility. Usually, this would be around 70 to 80 dB HL. Another method is to conduct the testing just below the LDL or UCL; the “Loud, but OK” level on the Cox 7 Point Loudness Scale. In general, it’s the same philosophy as when selecting a presentation level for word recognition testing in quiet—see Hornsby and Mueller, 2013.

The level of average speech, depending on how your system is calibrated, would be roughly 50 dB HL, or maybe a little lower. You would use this presentation level if you want to obtain some notion of how this person is performing with average-level speech, although remember, it’s probably a stretch to assume it represents how they do in the “real world”.

Another option would be to use a softer presentation level (e.g., around 35-40 dB HL) You may want to use a softer level such as this to demonstrate the impact that audibility has on understanding speech in background noise. For example, if the patient has the complaint of not being able to understand his grandchildren, soft-spoken wife, or other soft speech. By testing at a soft level, you can see how he is performing and validate his complaint. A softer presentation level can also highlight the benefit of amplification when used for unaided versus aided testing—this is the level where aided benefit will be the greatest.

The QuickSIN: A Reasonable Choice for Clinicians

I don’t have time to go through examples with all of the five tests I mentioned earlier. As I mentioned, the QuickSIN does seem to be one most commonly used by audiologists, so we’ll talk about that today. The QuickSIN is available from both Etymotic (see reference list) and Auditec of St. Louis. It also has

One of the great things about the QuickSIN is that the signal-to-noise ratios are pre-recorded on the CD. That means you don't have to worry about setting up your two-channel audiometer with speech in one channel, and noise in the second channel, and calibrating or syncing the two channels.

Each list is comprised of six sentences. There's only one sentence at each level. It starts at +25 SNR, which is basically listening in quiet. With each sentence, the four-talker babble background noise becomes 5 dB louder, until the final sentence is presented at 0 dB SNR.

For example, if the first sentence is presented at 75 dB HL, then the background noise would be 50 dB HL. For the next sentence, the background noise would be 55 dB HL, for the next one it would be 60 dB HL, then it would be 65 dB HL, then it would be 70 dB HL, and finally for the sixth sentence it would be 75 dB HL (which is 0 dB SNR). It's a female talker. According to the QuickSIN manual, the recommended presentation level is 70 to 75 dB HL, or if the person has a little more hearing loss, test at a “Loud but OK” level for that person.

It's very easy to administer. I would always use at least two lists (60 key words scored); using two lists is only 12 sentences. This goes very quickly and it's fairly easy to score.

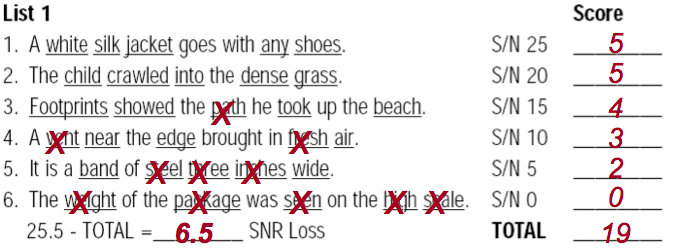

Figure 2 includes one scored list from the QuickSIN. The words that are underlined in each list are the key words. You see I’ve marked a red X on the words that the patient got wrong, and put the total correct for each sentence in the column on the right. There are 5 key words for each sentence. You simply total all the words that the person got correct, which in this case was 19, and subtract that value from 25.5 for the person’s score, which in this case is 6.5 SNR Loss.

Figure 2. QuickSIN sample list of six scored sentences.

You might wonder why we subtract the patient’s total correct from 25.5, when there are actually a total of 30 words. There are two things in play. First, you’re looking for the point that they get 50% correct, which would be 27.5. Secondly, Killion designed the test so that the score is reported in “SNR loss”. Normal hearing people would have a score of 2, in other words, they would miss 2 words out of the 30, so to obtain SNR-Loss, you subtract 2 dB which is how we get to 25.5. If you want to know the SNR-50 (maybe to compare to the HINT or the WIN), you'd have to add 2 dB to it to get the SNR-50 from the SNR-Loss. Most clinicians, however, have gotten used to using SNR-Loss, so that is what we’ll use today.

What does SNR-Loss mean for this patient whose score is 6.5 dB? A person with a score of 6.5 in a speech-in-noise situation either needs to turn the noise down 6.5 dB to hear like a normal hearing person, or he needs the person talking to make their voice louder by 6.5 dB. The guidelines from Killioin suggest that we interpret the QuickSIN socres as follows:

- 0 - 3 dB SNR-Loss Normal

- 4 - 7 dB SNR-Loss Mild

- 8 – 15 dB SNR Loss Moderate

- >15 dB SNR Loss Severe

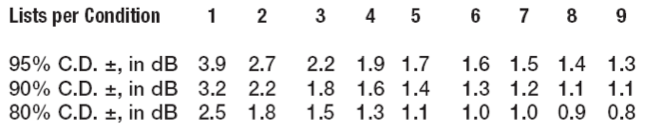

Critical differences are available for the QuickSIN so you can compare the score between the ears, or from a test at one point in time to another, and you will be able to tell if any differences are significant. Let's say that you did a QuickSIN on a patient and found a score of 8 for the right ear and 6 for the left ear using two lists. Are these scores significantly different? You can refer to the critical difference values (that are included in the manual with the test) to find out. If you want to use the 95% confidence level, and you used two lists, you will find from the values in Figure 3 that you need a 2.7 dB difference between the 2 scores before a difference really is a difference. If a person’s SNR loss was 8 in one ear and 6 in the other, you would report those as being the same.

When you do aided testing, these same critical differences can be used to compare aided to unaided, feature “on” vs. feature “off”, or Product A to Product B.

Figure 3. QuickSIN critical differences values.

Another important thing to know is not to use lists 4, 5, 13, and 16. Research has shown that those lists are either too easy or too hard and they don't fit in the critical range for all the other lists (McArdle and Wilson, 2006).

What I often hear from clincical audiologists is that is indeed does sound like a good idea to do speech-in-noise testing, but they aren’t too sure what they would ever do with the results. I thought I would take the QuickSIN test as an example, and pull out some illustrative cases, showing how these results may be helpful for you.

Case #1

Our first case is a young woman, in her early 30s, who reports working in a fairly noisy environment, having trouble understanding at work, and feeling exhausted at the end of the day. She is pretty sure she has a hearing loss. You do pure-tone audiometry and find that there is no hearing loss, in fact, no threshold level is worse than 15 dB. You did your ordered by difficulty NU-6 list and she scored 10 correct on the first 10 ( You can obtain the NU-6 Ordered by Difficulty list from Auditec of St. Louis. All 50 words are ordered by difficulty. There’s a protocol where if a person gets at least 9 out of the first 10 correct, you can stop your testing because you know at the .05 level of confidence that their final score is going to be 96% or better. See Hurley and Sells for more information.

The patient’s score on the NU-6 list tells us she obviously has no problems in quiet. Her QuickSIN score, though, was 5 dB for the right and 6 dB for the left. That's not normal. You now have objective evidence that her complaint is validated, that, indeed, she does have trouble in background noise. Now, what you're going to do about that is another issue, but imagine if you hadn't done the QuickSIN. You might think this woman has other things going on contributing to her problem at work but you wouldn’t suspect it to be a hearing issue.

This goes back to our optometrist example. She came in with a certain complaint and I think it's our ethical duty to test for that particular complaint. At least now you can validate her complaint. I don't think you're going to fit somebody with hearing aids who has normal hearing, but there are other strategies. You might do counseling as you would for somebody with central auditory processing disorder (CAPD). In fact, she may have CAPD.

Case #2

This person has a bilateral high frequency loss and really wants the least visible product available--CICs. You may want to fit him with mini-BTEs with bilateral beamforming, because you believe he will be more successful with them in background noise. This is the dilemma - you want to fit him with good directional processing, but he wants tiny “invisible” hearing aids that are not directional. What are you going to do? What if he had a QuickSIN score of 2 dB for the right ear, and 1.5 for the left - would that change your thinking? He has normal understanding in background noise. He understands in background noise like a normal hearing person; all he really needs is audibility. Maybe it would be okay to give him the product that he wants, because once you give him that audibility, he should do okay in background noise. Now, if his QuickSIN scores were 6 to 8 dB bilaterally, I think then I would be pushing much harder for good directional technology. Without the QuickSIN, you wouldn’t have this additional objective information on which to base this decision.

Case #3

The next person is really reluctant to obtain hearing aids, but is getting a lot of pressure from the family, who are frustrated with her inability to understand. It's an older woman and she says, "You know, I don't want to mess with these things—I certainly am not getting one for each ear. I know you told me I should get two, but I'm only going to get one." She seems pretty set in her decision. Her hearing loss is symmetrical and her word recognition is in the mid-80% in both ears. She has a typical, 30 to 70 dB downward sloping hearing loss. You ask about the telephone and she says, "I do fine on the telephone." What ear are you going to fit? What if you knew that her QuickSIN scores were 6 dB for the right ear and 12 dB for the left? Would that help you decide what ear to fit? I'm going for the ear that has the best speech-in-noise recognition. That would make sense to me. In case you’re thinking that putting the hearing aid on the bad ear would perhaps move the SNR-Loss from 12 dB up to something closer to the good ear, it’s unlikely that this will happen. Remember, we did the earphone testing at a high level, so the 12 dB SNR-Loss is not a function of lack of audibility—it’s related to cochlear function (or something more central).

Case #4

This patient is a new hearing aid user who was recently fitted bilaterally. As with most patients, his major complaint is having trouble understanding in background noise. He has a very symmetrical audiogram and symmetrical word recognition scores. His QuickSIN scores, however, are 6 dB for the right and 11 dB for the left. It's not too uncommon that you see asymmetry in the speech-in-noise scores, even when you have symmetry in everything else. He comes in a few weeks after the day of the fitting, and says that he is doing a lot better in most listening conditions . . . but (there is always a but) . . . says he experimented a little, and found that he does better at parties when he's only using his right hearing aid, not both. Well, that seems a little strange because of everything you know about binaural processing, but could it be that that better ear is the ear that he then is favoring in noise? While this complaint is a little unusual, you actually do have some evidence to say, maybe he could be right, because he does do better in background noise with his right ear. It could be that there's actually some detrimental effect when the left ear is added. We normally would expect people to at least do as well as their best ear when aided bilaterally, but there are cases, 5% to 10%, where the bad ear actually does interfere with the good ear. At least now, you're armed with some information to know that this is probably not a story he just made up so he has a good reason to return one of the hearing aids for credit. You actually have some documentation that, yes, indeed, one of the hearing aids could be detrimental in noise. What is you had never conducted the QuickSIN—what would your thoughts be then?

Case #5

This next patient is anxious to obtain hearing aids. He's having trouble understanding at dinner at his two favorite restaurants. You did the COSI, and his highest priority listening conduction is understanding at these restaurants. You've been to these restaurants and you know that during the dinner hour they have about a +8 SNR or so (because of course, like every good audiologist, you measured this with your handy cell phone app). His QuickSIN scores are 7 dB for both ears. You now fit him with good directional technology - bilateral beamforming. How is he going to do out at these restaurants? I would counsel the patient that I think he's going to do considerably better, because that extra advantage that I'm going to give him should push him right into the range where he should be getting at least 60 - 70% of the words correct, enough to follow conversations.

If we can give someone a 3 dB advantage in the real world with good directional technology, in theory, we should be able to take somebody from about getting about half the words correct up to about 80% correct. That's probably the difference between following a conversation and not following a conversation. To some extent, you can predict whether this outcome is possible from their QuickSIN score.

Case #6

Here’s another patient with a similar complaint. He is more of a party animal and hangs out a restaurant with a typical +3 to +5 dB SNR. His QuickSIN scores are 12 dB and 14 dB for the right and left ears. Right away, you know that even with good directional technology, it is very unlikely he is going to understand at these restaurants. Even though that's the number one item on his COSI, when you do your follow up visit he probably isn't going to be very happy when he goes to those restaurants. But, you knew that before you fit him. If it were my patient, I would want to tell him this before he leaves with his new hearing aids and comes back disappointed—establishing realistic expectations is important. Again, this is how you can use the QuickSIN to be a more effective counselor. But what if you hadn’t conducted the QuickSIN?

Case #7

We have an 80-year-old male, a long time hearing aid user, who says his right hearing aid isn't working as well as it used. In taking his history, you learn that he had a mild stroke about six months ago. You compare the test results from today to when he was fitted with his hearing aids two years ago. His hearing levels have not changed, nor has his word recognition, which is around 80% bilaterally. His left QuickSIN scores went from 6 to 7 dB, but in the right ear they went from 6 to 12 dB. Had you not conducted speech-in-noise testing, how would you have known that what he was talking about was his reduction in speech understanding in noise, not a problem with his right hearing aid?

Case #8

This person just purchased hearing aids a week ago, because he wanted to understand speech better in background noise. He's back today, saying the hearing aids really don't improve things in background noise. His pre-fitting QuickSIN scores were 8 dB for the right and 9 dB for the left. Why are the hearing aids not providing him benefit? You need to find out what background noise he's referring to. It may be that the SNR is 0 dB, which is true of some places.

You could conduct aided bilateral QuickSIN at average speech level in the soundfield (either your test booth or your fitting room should work just fine). All is well if he performs at the pre-fitting level, and, he actually should do slightly better than unaided (earphone results). Or, you could do a soundfield aided bilateral QuickSIN for soft speech. This should help convince the patient that hearing aids really do work in background noise, and the patient will notice this. . It may be that the complaint is simply related to unrealistic expectations.

I think these results can give the patient a shot in the arm regarding their speech understanding in background noise. In this case, I would conduct the QuickSIN at a fairly soft level, around 55 dB SPL. That's not an unreasonable level; it's only about 5 dB below average speech. You can do this in the sound booth, or through remote speakers, or even using your probe-mic speaker. I would use two lists, and in this case, score each SNR-level for the number of words correct (i.e., for two lists, you will have a total of two sentences for each SNR; a total of 10 words for each SNR).

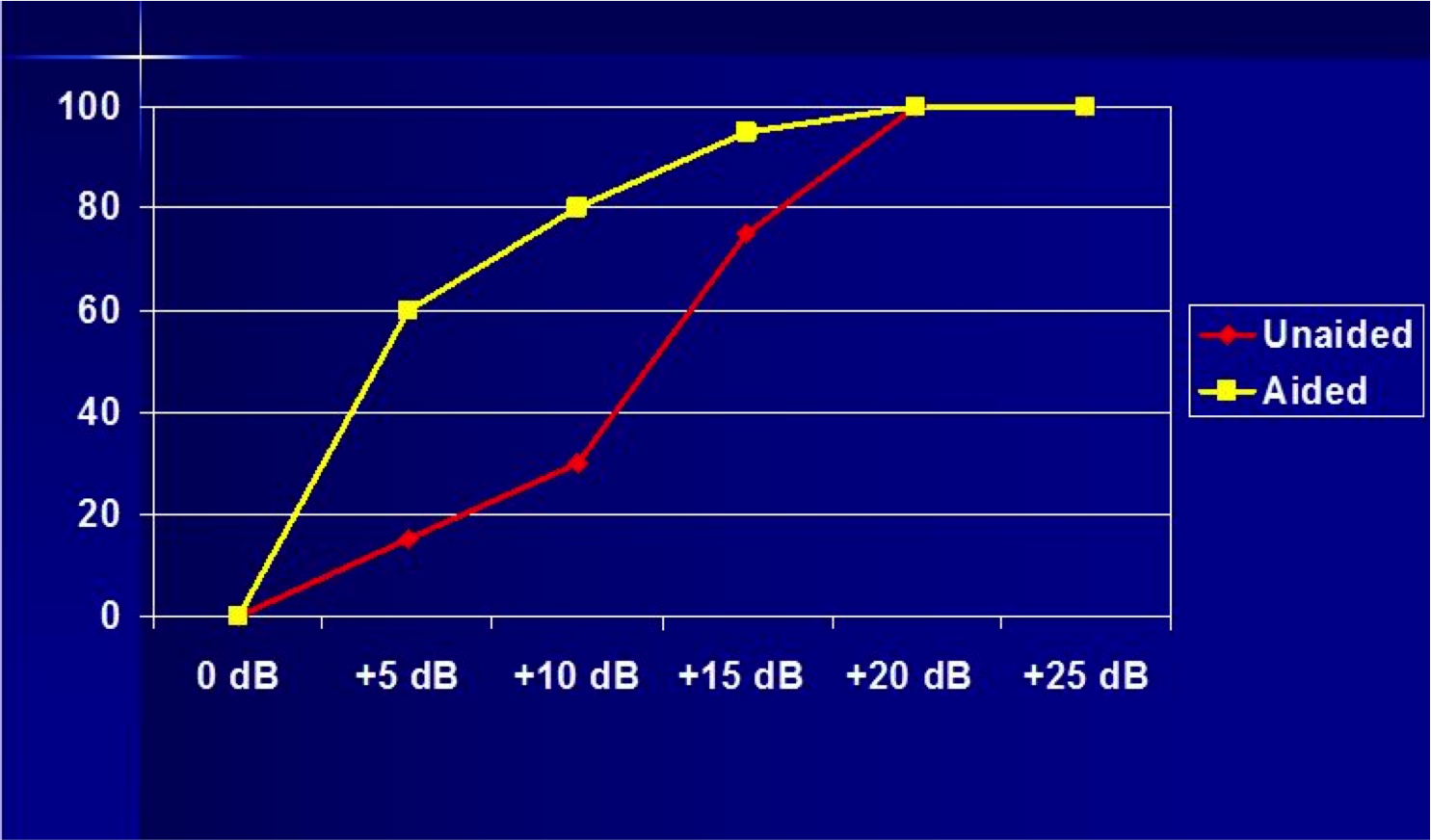

I have an example of a patient showing how this might turn out (Figure 4). I've taken the QuickSIN and scored it percent correct at each SNR level for both unaided and aided.

Figure 4. Best for patient counseling: QuickSIN results plotted on SNR chart for unaided and aided in soundfield (presentation level 55 dB SPL).

Along the bottom, on the x-axis, are the signal-to-noise ratios. If you do two lists that means he has 10 words for each SNR. On the y-axis are the scores on the QuickSIN in percent correct. I usually first plot out the unaided and aided scores, knee-to-knee with the patient, and talk about the differences. For example, you might discuss the results in Figure 4 like this: "When it's really quiet (+20 dB SNR to +25 dB SNR) you're doing okay, even without your hearing aids, if the speech is loud enough. When it's really noisy, like it is at the Blarney Stone at Sunday brunch during football season, where the signal-to-noise ratio is close to 0 dB, you're not doing well with your hearing aids, but nobody else is hearing well in that situation either. Even people with normal hearing are not doing well, so that's okay." Then, you spend most of your time talking about the improvements that the patient is getting with hearing aids at the +5, +10, and +15 dB SNRs. The scores plotted this way becomes a powerful visual representation of the benefit from the hearing aids, and makes it easy to discuss that with the patient. And . . .some evidence that hearing aids really do work in background noise!

Questions and Answers

Do you recommend conducting the QuickSIN on the day of a new hearing aid fitting?

Yes, I would consider the QuickSIN to be a vital part of a new hearing aid fitting, for the reasons I just discussed with Case #8. I guess maybe you’re asking that if you do it at the time of the fitting, is it really necessary to conduct the testing during the pre-fitting testing evaluation. I’d say yes. The QuickSIN only takes about 5 minutes to administer. If I were seeing a patient for a diagnostic evaluation, who I thought was a potential hearing aid patient, I would do the QuickSIN while they were already in the booth with headphones on. Since they are already set up, this will make things go even faster. These results will help you tremendously with your counseling. Now, you could wait until the hearing aid fitting, but I would try to work it into my pre-fitting testing if at all possible.

Historically, when you look at how many people are doing any type of speech-in-noise test, the surveys come back saying probably no more than about 20%, and actually, it’s probably lower than that. I know most audiologists say that they just don't have the time. One could argue that if you have the time to test monosyllables in quiet, why not use that time to do a speech-in-noise test instead? I know there are other reasons people have for not using speech-in-noise tests, but none of them seem like really good reasons to me. Speech-in-noise tests give you so much more information than testing in quiet, which audiologists seem to fond of. Of course, you're only going to do this testing with patients who are potential hearing aid users; you probably wouldn't do it with people who had normal hearing, unless they had a specific complaint of not understanding in background noise.

I encourage you all to jump in and give speech-in-noise testing a try. The QuickSIN is the most popular test being used. You can obtain that from Etymotic, or Auditec of St. Louis, where you obtain your other speech tests. Thank you all for your attention.

References

Bench, J., Kowal, A., & Bamford, J. (1979). The BKB (Bamford-Kowal-Bench) Sentence Lists for partially-hearing children. British Journal of Audiology, 13, 108-112.

Cox, R.M., Alexander, G.C. & Gilmore, C.A. (1987). Development of the connected speech test (CST). Ear and Hearing, 8(S): 119S-126S.

Etymotic Research. (2001). Quick Speech-in-Noise Test [Audio CD]. Elk Grove Village, IL: Author.

Etymotic Research. (2005). BKB-SIN [Audio CD and User Manual Version 1.03]. Elk Grove Village, IL: Author.

Killion, M. C., Niquette, P. A., Gudmundsen, G. I., Revit, L. J., & Banerjee, S. (2004). Development of a quick speech-in-noise test for measuring signal-to-noise ratio loss in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners.The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 116, 2395-2405.

Lindley, G. (2015). They say "I can't hear in noise," we say "Say the word base." Audiology Today, 27(4), 44.

McArdle, R.A., & Wilson, R.H. (2006). Homogeneity of the 18 QuickSIN lists. JAAA, 17(3), 157-67.

McArdle, R., & Wilson, R.H. (2008). Selecting speech tests to measure auditory function. ASHA Leader, 13, 5-6. doi:10.1044/leader.FTR5.13122008.5

Mueller, H.G., Ricketts, T.A., & Benter, R. (2014). Modern hearing aids: Pre-fitting, testing, and selection considerations. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Nilsson, M., Soli, S.D., & Sullivan, J.A. (1994). Development of the Hearing in Noise Test for the measurement of speech reception thresholds in quiet and in noise. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 95(2), 1085-1099.

Walden, T., & Walden, B. (2004). Predicting success with hearing aids in everyday living. JAAA, 15(5), 342-352.

Wilson, R.H., Carnell, C.S., & Cleghorn, A.L. (2007). The Words-in-Noise Test with multitalker babble and speech-spectrum noise maskers. JAAA, 18, 522-529.

Wilson, R.H., & McArdle, R. (2008). Change is in the air – in more ways than one. Hearing Journal, 61(10), 10,12,14-15.

Citation

Mueller, H.G. (2016, September). Signia Expert Series: Speech-in-noise testing for selection and fitting of hearing aids: Worth the effort? AudiologyOnline, Article 18336. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.