Learning Objectives

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the current regulations related to hearing aids and how these impact potential over-the-counter versions of devices.

- Discuss the pros and cons of an OTC model of hearing aid access.

- Describe the data that supports what an audiologist contributes to the hearing aid fitting process.

Introduction

I'm probably no more of an expert on the topic of over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids than you are. In this presentation, I'm going to review the events that have occurred to bring us to this point with OTC hearing aids, and look at some data so that we can further discuss this issue. In my position as the Director of the Au.D program at the University of Pittsburgh, and Director of Audiology for the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, I think about how over-the-counter hearing aids and other devices will impact our clinical activities. I see patients every week and most of my work is focused in amplification. I work with all of the hearing aid manufacturers in the industry in some capacity, whether that is using their products in the clinic, conducting research, or lecturing. I was not on the committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine that looked at accessibility and affordability of hearing health care in adults, but I was a reviewer of the report from that committee. That report was one of the many factors that I'll discuss today that had an impact on the movement toward over-the-counter hearing aids. I will try and be clear in today's presentation in terms of what is evidence-based or fact, and what is my opinion.

Given the title of this talk, the first question you might ask yourself is, opportunity or disaster for whom? Am I focused on the audiologist, or the person with hearing loss? We need to consider both the audiologist and the person with hearing loss when we consider the topic of OTC hearing aids. At the end of the day, we have to focus on the person with hearing loss, but as audiologists our profession plays a very important role in consumers' success with amplification so we have to consider the effect on us as well.

Background

It is helpful to review events leading up to the current status of OTC hearing aids. I've organized a timeline beginning with 2009.

2009: NIDCD Working Group

I think the first clear statement that pushed towards this over-the-counter hearing aid discussion was a meeting of the National Institute for Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), which is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In August 2009, the NIDCD convened a meeting called, Working Group on Accessible and Affordable Hearing Health Care for Adults with Mild to Moderate Hearing Loss. The stated purpose of this group included the following: "To develop a research agenda to increase the accessibility and affordability of hearing health care for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss, including accessible and low cost hearing aids." The NIH is stating that something has to be done to increase accessibility and make hearing aids more affordable to people with mild to moderate hearing loss, in order to drive research or other activity toward this end.

2009: FDA Guidance on Hearing Aids and PSAPs

Also in 2009, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), began talking about personal sound amplification products (PSAPs). PSAPs are different from over-the-counter hearing aids. Back in 2009, no one was talking about OTC hearing aids yet, but, there was a lot of discussion around PSAPs. The FDA started to look at their regulations related to hearing aids to see if and how they might apply to PSAPs. They decided that PSAPs didn't fit in with their hearing aid regulations. As such, they made it their goal to define through labeling the difference between a hearing aid and a PSAP. A hearing aid is a wearable sound-amplifying device that is intended to compensate for impaired hearing. The PSAP, on the other hand, is intended for someone who is not hearing impaired; it is not meant to compensate for impaired hearing. It is suited for someone with normal hearing who would like to amplify sounds in specific situations (e.g., recreational activities). Many people with hearing loss can go online and get PSAPs, which do provide amplification and can help them in certain environments. It was determined that PSAPs would not be regulated by the FDA, and that traditional hearing aids would continue to be regulated the way they had always been.

2013: FDA Draft Guidance

A few years later in 2013, the FDA set forth new guidelines for PSAP advertising, including a list of things that PSAPs are not intended to do. Their aim was to achieve more clarity, especially in terms of labeling and differentiating medical devices from electronic products. The FDA stated that PSAPs are not intended to address listening situations that are typically associated with and indicative of hearing loss, such as:

- Difficulty hearing a person nearby

- Difficulty hearing in a crowded room

- Difficulty understanding movie dialogue in a theater

- Difficulty hearing on the phone

- Difficulty hearing in noise

- Cannot be considered an over-the-counter substitute for a hearing aid

These guidelines were met with much frustration from the people who make PSAPs, because they felt that they couldn't label their devices accurately if they were being restricted from making any of these claims. One of the items listed was that PSAPs are not intended to address difficulty hearing in noise. However, there are a variety of PSAPs on the market that include applications where you can use your phone as a microphone, and those that involve using an offset microphone that might allow a person to hear better in noise. Yet, the FDA guidelines are saying that you can't make that kind of claim. This continues to be a source of frustration for people who are trying to label these devices appropriately.

2015: PCAST

In 2015, the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) came out with a document many of you may have seen. They compiled a list of issues that people involved in the hearing aid industry should be thinking about. One item that they put into writing is that the FDA should approve a distinct class of hearing aids for over-the-counter (OTC) sale, without current requirements for consultation with a professional. They didn't go into too much detail about what this would be, or what it would look like. Essentially, PCAST challenged the FDA to create this new class of hearing aids, with the belief that it would open up some affordability issues, accessibility issues and be something that consumers could pursue. Officially, this was the first time that over-the-counter hearing aids were addressed, although within the industry, we've talked about it for years.

2016: FDA Meeting

In 2016, the FDA predictably responded to the PCAST document with a meeting. The key speakers at this meeting were the usual suspects from the hearing instrument industry (e.g., HIA, ASHA, AAA, etc.). Mainly, they asserted views that were in opposition to OTC hearing aids. Some people questioned the need for a distinct FDA sub-category for over-the-counter hearing aids. They speculated that if PSAP manufacturers were allowed to label their products appropriately, and had some electronic industry oversight, would that serve the same purpose as OTC hearing aids? Whether it would have or not, ultimately that's not the path people have gone down at this point.

2016: NASEM (IOM)

In 2016, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM, also known as The Institute of Medicine, or IOM) came out with their overarching report. If you want to read the report in further detail, there is a PDF that you can download. For the purposes of today's presentation, I want to draw your attention to a couple of their recommendations. First, they proposed removing the requirement that an adult needs medical clearance before obtaining a hearing aid. Removing that requirement is part of clearing the pathway to an over-the-counter type mechanism to obtain amplification. To be clear, the FDA has not removed the requirement, however they did announce that they will not be enforcing that requirement. The requirement stays on the books. Usually that's done so they can have a year or so and see what happens. If for any reason they feel like there are adverse events, they can simply put the requirement back in place because they've never really taken it away. Or, they can remove it officially. Right now, they haven't removed it; they simply aren't enforcing it.

Next, NASEM went on to address over-the-counter hearing aids. Similar to PCAST, NASEM advocated that the FDA should create a new category of OTC hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss, so that it can be regulated by the FDA. OTC hearing aids are going to look very different from traditional hearing aids, in terms of the regulations, the standards and the target demographic. At this point, none of that is defined. However, it is important to note that the intent of NASEM's report was to strongly encourage the FDA to pursue this new OTC category.

Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act of 2016

Elizabeth Warren, a Democratic senator from Massachusetts, and Chuck Grassley, a Republican senator from Iowa, worked together on a bipartisan bill, the Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act of 2016. Their bill was submitted to the legislature in December of 2016. Their proposed legislation was an attempt to put the PCAST and NASEM recommendations into action and be made into law, as a way to force the FDA's hand. The congressional session ended before any action could be taken on that bill. During that same timeframe, in December of 2016, the FDA announced a change in medical clearance rules. They stated that they would not enforce the requirement that adults 18 and older receive a medical evaluation or sign a waiver prior to purchasing hearing aids. This was a clear move paving the way for OTC hearing aids. Furthermore, in that same document, the FDA announced that they're committed to considering creating a category of over-the-counter hearing aids.

Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act of 2017

In 2017, the same senators and many of their colleagues in both the senate and the house reintroduced the bill, which was renamed the Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act of 2017. To make their case that the bill should move forward, Warren and Grassley published an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association in March of 2017 (an uncommon forum for a politician). Once again, their assertion was that these recommendations from PCAST and NASEM should be put into action. Currently, that's where we are now, with this bill in front of the senate and the house. If this legislation is passed (which at the time of this webinar, it has not), the bill states that the FDA would have to look at methods to assure OTC hearing aid safety and efficacy, to define the output limits on these devices, and to oversee the labeling. Most recently in these hearings, there has been a lot of focus on what the labeling would look like and how these sales would be permitted. That is all work that still needs to be done.

When the bill was resubmitted in 2017, they removed some original language from the 2016 version. First, they took out the language which asked the FDA to remove the draft guidelines about the PSAPs, and what the PSAPs could not claim to do. They also removed language charging CMS to consider reimbursement for audiology services (those that are more related to hearing aids and amplification). Clearly, they were trying to streamline this bill and not bring in other pieces that might slow down the approval process.

Not to be left out, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) held a workshop in April 2017. As the purpose of the FTC is to protect consumers, their workshop focused on examining competition, innovation and consumer protection issues raised by hearing health and technology, specifically hearing aids.

Position Statements on OTC Hearing Aids: ASHA, ADA, AAA and AAO-HNS

In February 2017, ASHA put forth their position statement on policy related to OTC hearing aids. One of the things they stated is that OTC hearing aids are not a cure-all. This may be a great idea and a pathway that helps some people, but there are a large number of people who need more complicated services for whom OTC devices would not be appropriate. ASHA's stance is that there are still a lot of issues at hand, and they want to ensure that insurance coverage of hearing aids is not undermined. They don't want programs to go away because some legislator decided that the problem is fixed, and now these other programs aren't necessary.

Next, the Academy of Doctors of Audiology (ADA) came out in support of the OTC Hearing Aid Act of 2017. They also asked for the draft guidance to be removed (which of course, it wasn't). The American Academy of Audiology (AAA) also came out with a statement, which was neither for or against OTC hearing aids. Their stance was more to say if you're heading down this path, there are some important items to include in any move toward OTC. They specifically emphasized the negative consequences of underfitting. When audiologists use first-fit strategy without evidence-based measurements, the consequence of that is generally underfitting (this is a problem whether a device is over-the-counter or not).

The American Academy of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) also stated their position of what they would want to require with regard to OTC hearing aids. First, they would recommend a medical evaluation followed by a standardized hearing test before someone could purchase this device. However, if this bill indeed passes, requiring a medical evaluation and hearing test takes away the accessibility and affordability component of OTC hearing aids. They also wanted some requirements related to standardized packaging and labeling, which is actively being worked on. Finally, they wanted a structured mechanism for at least five years of data collection as a way to monitor results and determine if any bad effects do occur. Currently, the language in the bill is worded such that they're suggesting two years of data collection to follow up with OTC hearing aid users.

Where is the Bill Now?

[Editor's note: The "Where is the Bill Now?" section of this text course was updated in December 2017 to reflect the change in legislation since this course was originally recorded in July 2017.]

This bill was attached to another bill known as the "must-pass" Medical Device User Fee and Modernization Act (MDUFA), FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017. This bill was passed in August 2017.

In order to pass a bill, it needs to go through many committees. Along the way, they mark it up and change some language. Many legislators were worried about how many things were attached to this FDA Reauthorization Act. One solution to speed things along is to take items off the bill, or to water things down a bit. For instance, at one point Representative McKinley added an amendment stating that there needed to be a test performed by a licensed hearing care professional. That amendment was withdrawn. At the end of the day, if you're going to have an over-the-counter option, you're not going to be able to require that kind of testing. Other concerns raised were preventing OTC hearing aids from being restricted at the state level. Labeling requirements has been another hot topic, as well as reporting any adverse events that occur.

Now that the bill has passed, the FDA has three years to specify this new category in terms of technical requirements, and rules for labeling and marketing devices that will fall into this category. So today, over-the-counter hearing aids do not exist. They cannot be marketed legally. I think that it's easy to confuse OTC hearing aids with Internet/online sales of hearing aids. In some states, Internet hearing aid sales are legal, and people can buy hearing aids over the Internet. However, that is very different from an over-the-counter hearing aid, which currently does not exist.

Even though the category of OTC devices has yet to be created, there have been many press headlines expressing a wide variety of viewpoints. For example:

Hearing Aids at the Mall? Congress Could Make It Happen

Scientifically Rigorous Study Shows Older Adults Benefit from Hearing Aids; Support for OTC Devices

6 Reasons Why You Should Never Buy Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids

Hearing Aid Makers Have Differing Takes on OTC Sales Option

Additionally, audiology professionals have varied reactions about this topic. On one end of the spectrum, some people believe that OTC hearing aids will bring about the end of audiology, or the end of their career, and they feel this is a disaster. Others are more resigned, with the view that OTC sales are going to force our hand and we're going to have to think about unbundling. Some feel that we should embrace this change, and that they are up for the challenge.

The Hill is a newsletter used for the Senate and the House of Representatives. It is read by many members of congress and their staff. They have published several opinion editorials (op-eds) about over-the-counter hearing aids. There have been consumer op-eds of the viewpoint that OTC hearing aids would be a good thing. Some professionals who work with geriatric populations have stated that these products would make a difference for patients. At least two otolaryngologists have responded in this forum; one was very much in favor of OTC hearing aids, and the other stated they could be frightening, from a medical perspective.

Surprisingly, the Gun Lobby also expressed their opinion about OTC hearing aids. The attitude of audiologists tends to be that OTC hearing aids is a deregulation. The thought being that the FDA regulates hearing aids a certain way and if OTC hearing aids become available they will represent a deregulation. On the contrary, it will actually be a new regulation since OTC hearing aids would be a new category for the FDA. The Gun Lobby is opposed to more regulation. Their stance is that PSAPs already exist, and can be purchased right now at the hunting store over-the-counter, and they are not regulated. In their opinion, this is just going to add on regulation, and probably increase the price.

Looking at the Data

We have very little data on OTC hearing aids because there are no OTC hearing aids marketed yet. That being said, it's probably reasonable to pull data from the direct-to-consumer studies (i.e., consumers buying devices from the Internet or directly from a store). I looked at the direct-to-consumer studies listed in the course handout.

There were a range of findings from these studies. The biggest finding is there are a wide range of direct to consumer devices. You have devices with quite good sound quality and an acceptable bandwidth. The least expensive devices had the worst sound quality. Some devices have mid-frequency gain only. Some people stated that the physical fit wasn't comfortable, or they didn't like how it looked, that it was too visible. Typically, the direct to consumer hearing aids are worn for fewer hours, although this may be related to the belief of consumers that they have a milder issue with their hearing.

Humes et al. (2017)

One study that has received a lot of attention this year came out of Larry Humes's lab in March of 2017, and was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). It was published in the American Journal of Audiology, and titled, "The Effects of Service-Delivery Model and Purchase Price on Hearing-Aid Outcomes in Older Adults: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial" (Humes et al., 2017). When it first came out, this study received a lot of press, although it was subject to a wide variety of interpretations. In Science Daily, they claimed that the study was, "The first ever placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of hearing aid outcomes" showing that "older adults benefit from hearing aid use." While there have been lots of studies that have shown older adults benefit from hearing aid use, it is true that there haven't been any that have been placebo controlled. HealthDay News stated that, "Solid evidence about the value of hearing aids has been lacking -- until now." That's kind of a tough one to swallow because there have been quite a lot of well-done studies to demonstrate the benefit of hearing aids, including one out of the VA, as well as a more recent study out of Robyn Cox's lab. United Press International (UPI) interpreted the study, indicating that "Seniors with hearing aids benefit most with proper fit, instruction." Conversely, the NIH offered their interpretation, asserting that the "Model approach for over-the-counter hearing aids suggest benefits similar to full service purchase." Let's all look at it together and you can form your own opinion.

This study looked to determine the efficacy of hearing aids in older adults using two models: the audiology best practices model, and the alternative OTC model. Since the OTC model does not exist yet, they had to do the best they could. Instead of calling it OTC, they referred to it as CD (Consumer Decides).

Participants were adults between the ages of 53 and 83 years old. They had 154 people with mild to moderate, bilaterally symmetrical sensorineural hearing loss. None of the subjects had any previous hearing aid experience. They used a high-end mini-BTE open-fit hearing aid. All of the participants received hearing aids with the same features (directional microphone, dynamic feedback suppression, noise reduction and four push-button memory used as VC). They divided the participants into three groups:

- Audiology Best Practices (AB) group: In the AB group, there were 53 participants. Their hearing aids were programmed to NAL-NL2 target, based on an audiogram. They only verified the 65-dB mid-range input. They looked at loudness discomfort and then they had a 45-60-minute orientation session.

- Consumer Decides (CD) group: In the CD group, there were 51 participants. They had three different sets of hearing aids they called X, Y, and Z. These were programmed (NAL-NL2) to match the three most common patterns of hearing loss in older adults. They had a push button, so they could use volume. And they had the same basic features as the AB group.

- Placebo (P) group: In the placebo group, there were 50 participants. They used all the same factors as the AB group, except that the hearing aids were set to 0 dB insertion gain for the 65-dB input. Half of these hearing aids had some directionality, half didn't. The directionality probably makes it not quite a placebo condition, because you have some directionality.

Outcome measures were obtained before and after a six-week trial, and following 4-week AB-based trial for CD & P. For participants in the CD and the placebo groups, those who did not want to keep the hearing aid that they had at that point were offered the chance to go into the best practices model to see what would happen.

They conducted the following tests/inventories to obtain unaided baseline measures and outcome measures:

- HHIE: Hearing Handicap Inventory - Elderly

- CST: Connected Speech Test

- PHAPglobal: Profile of Hearing Aid Performance (5 communication subscales)

- PHAPavds: Profile of Hearing Aid Performance (2 distorted/aversiveness subscales)

They concluded that hearing aids are efficacious for older adults, for both the AB and CD delivery models, with the CD model yielding only slightly poorer outcomes than the AB model. At the end of the day, they were feeling pretty good about both those outcomes.

My Thoughts and Interpretations

In this next section, I am offering my personal opinions and interpretations of this study. You may have other interpretations.

Things to Keep in Mind

I don't believe that the CD group mimics a typical OTC model, because 42% of the original participants were rejected from the study. In other words, they were not allowed access to the hearing aids. If you go into a Walmart store to buy an OTC hearing aid, they're not going to reject you. You're going to be able to purchase one.

Additionally, I don't think the AB group mimicked true best practices. Best practice is all about customizing, both acoustically and physically. Acoustically, we certainly would not only match targets for 65 dB SPL and max output. Physically, you would make an ideal solution for the person, which could be a ear molds (which were not used in this study). These were all slim tube to dome fittings.

I find the placebo group to be problematic in that 0 dB gain was for 65. We know that for a lower input level, it would have had gain. There would have been a minimal amount of benefit in that group. It's still a pretty good example of placebo, but it's not a true placebo. Furthermore, these were all people that could have afforded $3600 hearing aids, because that was one of the requirements of this study.

Interesting Data

There are a few pieces of data from this study that I find to be the most interesting.

- In the CD group, 90% of participants tried two to four hearing aids. In the over-the-counter realm, I'm not sure that model would exist, depending upon where consumers purchase their OTC hearing aids.

- Also in the CD group, 20% of the participants needed to come in for extra help to figure out how to use the hearing aids, even after they had the video and handouts. As clinicians, if we offer or support over-the-counter hearing aids, we need to make sure that we've unbundled in a way that we can provide services to people in our clinics, and we can charge for those services.

- When participants in the CD and placebo groups moved to the customized fit, the majority of them ended up keeping their aids. Clearly, it did matter to them to have that customized care.

- The data in the study supports the need for ongoing, routine maintenance appointments. As these people came in as part of the study, they found that microphones were clogged with dirt, and there were a variety of other things impairing the function of the devices. If that's something you do, these data are useful to reinforce that you're doing the right thing.

Important Points

In the CD group, some of the participants who went on with the study ended up keeping their hearing aids once they had the audiologist-driven protocol. Interestingly, 36% of the placebo folks who had very little gain wanted to keep their hearing aids. If you feel like arguing against over-the-counter hearing aids, this would be compelling data because this indicates that people have no idea how to accurately judge adequate amplification.

In the Consumer Driven group, 73% percent of participants picked the wrong aid based on their audio and the three NAL-NL2 choices. Again, this indicates that consumers can't make accurate choices about the hearing aid that is best for them. However, it's interesting that Humes used those three typical configurations and fit to NAL, and those all produced better audibility (as per results from the Speech Intelligibility Index) than manufacturer first fit. If you happen to continue to practice using manufacturer first fit without verification measures and subsequent fine tuning, these people were all better off doing this on their own.

OTC Hearing Aid Acceptance

What if we embraced over-the-counter hearing aids? If we assume that these products and this OTC pathway will exist, why are we resisting them? Some common reasons why hearing care professionals are slow to accept the OTC movement include the following:

- They are not fitted by an audiologist

- They could be harmful

- They are not purchasing hearing aids

- OTCs are not traditionally programmed for their hearing loss

A different way to approach it would be to accept OTC hearing aids for what they are. There may be some situations where OTC products won't be ideal; however, we can take the stance of emphasizing what audiologists can bring to the table. We can stress why we are a key player in helping clients with both traditional and over-the-counter hearing aids.

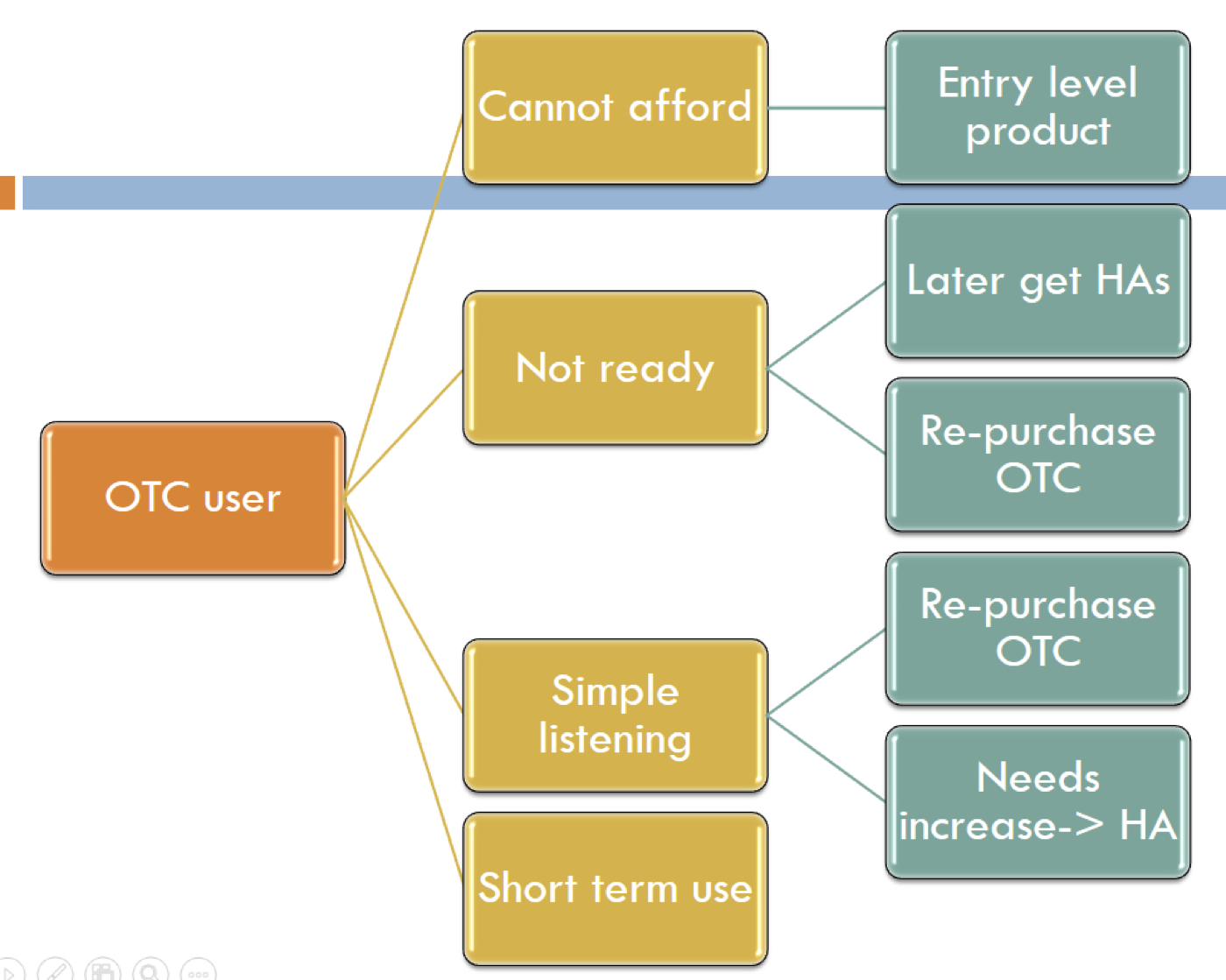

Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the potential path of an OTC user. Some people may not be able to afford the traditional hearing instrument pathway, or they're just not ready for hearing aids. They're the kind of people who acknowledge they have a hearing problem, but they convince themselves that they don't have a $3,000 problem. They believe they have simple listening needs, or there is some kind of short-term use where an OTC product might make better sense.

Figure 1. Potential path of an OTC product user.

Regardless of whether a person chooses the OTC pathway or the traditional hearing aid pathway, as audiologists, we can help people with either scenario. Even if they don't require much from us at the very beginning, we would like to be part of their hearing improvement journey. That way, if they have greater needs in the future, or if they want their devices to be smaller or more custom fit, they're already connected to us. The idea is that when the patient makes the decision to purchase an OTC hearing aid, they are now taking an active role in improving their hearing. It may be that an OTC is the best thing for them at first, because they will take action. Financially, I would certainly rather these people be paying me, rather than making their purchase at Best Buy or Walmart.

One way to think about the OTC model is that they are just another category, but a category patients can access through you. Instead of viewing the OTC movement with negative emotions, we can see it as another pathway. We should not predict that OTC hearing aids are going to injure people and that it will be a terrible disaster. On the other hand, it is also inappropriate to view OTC hearing aids as a cure-all for every situation. When you look at all of the people with hearing loss and their varying levels of need, one would expect to be able to choose multiple pathways. Up until now, we've really only had one pathway that has been very constrained. This is a venture into a new pathway, which may open up other pathways in the future. As an audiologist, I would still prefer that all these pathways run through my clinic or be associated with my clinic. Initially, we could work with patients online if there are accessibility issues, but again, you'd already be connected and they could reach out for further assistance, if needed.

About eight years ago, we conducted a study that was intended to predict if people would purchase hearing aids (Palmer et al., 2009). On a scale of one to ten (one being the worst and ten being the best), we asked people to rate their own hearing ability. Those who scored between 1-5 were most likely to pursue amplification (75-100%). People who scored between 6-7 needed more counseling. However, people who rated themselves between 8-10 were the least likely to purchase amplification. This last group perceives themselves as not having much trouble with their hearing. This group could potentially be our OTC users. They may be having some issues, but they aren't ready for traditional hearing aids. These are definitely people who could benefit from audiology assistants as they enter the pathway to hearing improvement. Because there will be no FDA licensure requirements for distributing OTC hearing aids, an audiologist is not required to do a fitting. The audiology assistant would be able to conduct the basic fitting of tubing/dome, instruct the patient on batteries, cleaning, and insertion/removal.

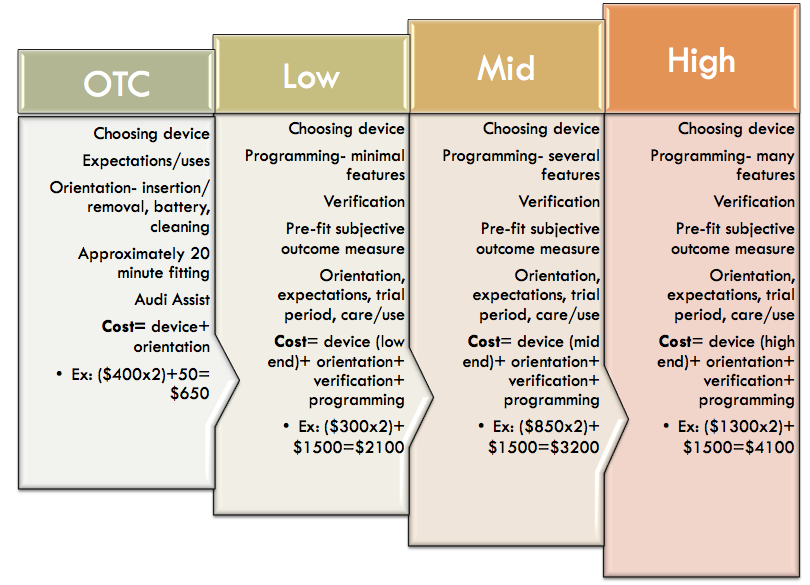

Figure 2 shows some mocked-up figures to provide an idea of how you could unbundle your services in the clinic, if you were to incorporate OTC products. Even if people purchased the products elsewhere, you could still welcome them into your clinic and provide services to them, and they can pay as they go and get the help that they need.

Figure 2. A mock example of how unbundling might work for OTC products in a hearing care practice.

Over the last four months, in our practice, we have been experimenting with a new way of thinking about and talking about levels of hearing aid technology. We use the terms basic, standard, advanced and premium to describe the differing levels of technology in our hearing aids. We have tried to arrange our materials such that these different levels are not presented as a hierarchy. We don't want patients to see these levels and automatically presume that premium must be the best and basic must be the worst. We try to educate our patients that there is no one best hearing aid for all people, but there is going to be a best hearing aid for you. It is up to us as the hearing care professional to do the work we need to do to figure out the patient's hearing requirements.

This approach also aligns with Robyn Cox's data, that show there are not data to support advanced and premium hearing aids. The standard hearing aid is the target. The "non-custom" option is our concept of having our own over-the-counter hearing aid. It is a basic hearing aid that we're selling for just above cost. An audiology assistant can help the patient select the proper tubing length and the proper dome, how to open and close the battery door, and how to use the volume control, which may be all they need. Because we're going to administer a hearing test, we do advise people whether the non-custom option is a good idea for them, based on their hearing loss. If it is a reasonable option given their needs, they can start there. We have instituted a mechanism whereby the patient can later pay the difference between the basic service and move into full service, at which point they can have all the programming and help that they need. This is our concept of how we might eventually wrap OTC products into our practice, where patients could get a device from our clinic that is an actual hearing aid. Then we can, in a sense, unlock it for the customization. It is unlocked in terms of features, but we're going to offer the option of customization including verification and support, etc. We've had a few people take us up on this, and so far, they're doing well. The majority of our patients choose to use our more standard process, however at this point, we are still finetuning this model.

How do you Differentiate Yourself?

I believe that differentiating ourselves begins with customization, and matching the right level of technology to each patient's needs. Additionally, we can provide the physical coupling of the device to the patient's ear, the importance of which is often minimized. We can use custom ear molds, and not default to domes (which is going to be very much part of over-the-counter type of devices). Audiologists can provide the best acoustic fit, measured in the individual ear canal, because that's currently the fastest, most efficient way to make sure we've given the person audibility, which is the only treatment for hearing loss. We will need to unbundle our pricing, so people can come to us with whatever device they currently have. Ideally, makers of over-the-counter products will include the ability for them to be "unlocked" by an audiologist. In other words, a person could buy OTC hearing aids, but if they decided that wasn't enough, they could come to an audiologist with that device, and the audiologist could use their expertise to fit it and customize it to the patient.

Evidence-Based Practice

Another service we can provide to differentiate ourselves is verification. We can measure the output of a hearing aid in the individual’s ear, and match that output to an evidence-based target. According to data from Robyn Cox's lab (Cox, Johnson, & Xu, 2014), the fitting is the most important part of returning audibility to a patient. If you fit a hearing aid well, whether it's a basic or a premium hearing aid, and if you fit it so the sounds are audible, people will do well. In terms of the basic things people want to be able to do, the fitting is the most important component of returning audibility, regardless of technology level. Best-practice fitting protocols (matching outputs across input and frequency to evidence-based targets) optimize results for every patient, leading to improved speech understanding and quality of life.

Leavitt and Flexer (2012) found a similar result in their study on the importance of audibility in successful amplification of hearing loss. They looked at subjects' word recognition scores in noise obtained on the Quick Speech in Noise Test (QuickSIN) for six pairs of premium hearing aids set to the manufacturer's first fit, as well as with a pair of old analog hearing aids fit and verified to NAL targets. When using first fit, people did not even perform as well as with the old analog hearing aids. When you fit and verify to NAL, you're giving people actual benefits; that's what we bring to the table as audiologists. That's something you can't do over-the-counter, because an OTC model can't account for an individual's ear canal.

Harvey Abrams and colleagues (2012) reported a similar finding. They used the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) to obtain people's preference for "initial" versus "verified prescriptive" fitting. According to APHAB scores for their participants, 15 out of 22 people preferred the verified prescription.

Sergei Kochkin (2014) did some compelling work related to this topic. He compared consumer satisfaction, subjective benefit and quality of life changes associated with traditional and direct-mail hearing aid use. Again, direct mail is not the same as over-the-counter, but it's the closest thing we have. Interestingly, he compared direct-mail to how many kinds of best practices the audiologist brings to the table in any of these fittings. For example, a minimal hearing aid fitting protocol including only one best practice would be only measuring the audiogram. A comprehensive hearing aid fitting protocol would include measuring the audiogram, conducting verification and validation, aural rehabilitation, etc. He sought to find out how direct-mail hearing aids compare to traditionally fit hearing aids. He also looked at the impact of best practices on performance of traditionally fit hearing aids in comparison to direct-mail hearing aids. Kochkin used two MarkeTrak surveys for his data. The first survey was conducted in 2009, and it collected data from 1721 people who had been fit with traditional hearing aids. The second survey from 2013 collected data from 2332 customers of a large direct-mail hearing aid firm.

He found that the traditionally fit hearing aids delivered by the highest level of best practices yielded the most overall consumer success. And, direct-mail hearing aids provided more success than those delivered with a minimal hearing aid fitting protocol that included only a few best practices.

Kochkin, Dennison, & Jackson (2014) looked at users' customer loyalty quotient (CLQ). As audiologists, we want customer loyalty. We want our patients to be recommending our services to their friends, rather than purchasing hearing aids at the store. Kochkin and team looked at a national survey of 3174 hearing aid users to determine the following:

- Consumer satisfaction with their hearing healthcare provider (HHP)

- Consumer loyalty ratings with HHP

- The impact of consumer satisfaction on loyalty

- The relationship between consumer loyalty and best practice

They used a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very dissatisfied; 7 = very satisfied), and asked participants to rate the professional on 7 factors:

- Professionalism

- Knowledge level

- Explained care of hearing aid

- Explained hearing aid expectations

- Quality of service during fitting

- Quality of service post-fitting

- Level of empathy

They found that the more best practices that the professional brought to the table, the more loyal the patient. Consumers realize that when you're providing more services and best practices, that you're bringing something superior to the process. They found that when only a few best practices were used in a fitting, patients fell into a "zone of serious defection". Patients in this zone have a low level of loyalty, and are likely to go to someone else, or maybe go online to purchase devices. They don't feel particularly connected to the professional or that they're getting anything out of the ordinary.

They also looked at the data in terms of the relationship between consumer loyalty and verification/validation. The lowest loyalty quotient was given by those patients who received neither verification nor validation. The highest loyalty quotient was given by people who received both verification and validation.

Summary

To conclude, we are still in the middle of this process, because OTC devices don't exist yet. I would expect we would see hearing aid manufacturers offer these devices in the future now that the bill has passed. As it stands, we don't know what the FDA requirements will be, in terms of limiting output, gain, and those types of things. Another piece of the puzzle to be addressed is how these OTC products and services will be reimbursed. That's an accessibility/affordability issue that is arguably more complicated.

In summary, I believe that OTC devices will offer consumers a new pathway; one that absolutely can and should be run through our clinics, whatever form that may take (physical appointments, over the Internet, or via telephone). We need to prepare to offer services to people who may already have an OTC device. Additionally, we need to offer our services at a fee; as such, it is important to make people aware that we are offering something far more than a device. We have to be able to tell our story, in order to differentiate our services so the consumer can see what they will get if they visit a hearing care professional, versus picking up the devices at the corner drug store. We have expertise. We're going to take into account the physical ear canal, the person's lifestyle, in order to create a solution which is quite different from what you could get over-the-counter. Having said that, I think there is still going to be a group of people for whom the over-the-counter products will be just fine, at least for a certain amount of time. In any event, the audiologist will definitely have a part to play in the OTC hearing aid market.

Questions and Answers

Will the consumer be made aware that if they purchase a OTC product, that they must use it at their own risk?

Yes, they will be made aware that it is at their own risk. A big piece of this will be how the product is labeled. We need to be clear that these products are not for children; they are for adults. I like to use the analogy of taking Aspirin. When I have a vicious migraine, I choose to take over-the-counter medicine. Clearly printed on that bottle, it indicates that if your pain doesn't stop in the next 24 hours, you should see a doctor or go to the emergency room. The labeling on over-the-counter hearing aids will have similar warnings.

What about people who suffer from tinnitus? Will they be able to use OTC hearing aids? Have you heard of any tinnitus maskers being included in over-the-counter?

The subject of tinnitus has come up at some of these committee meetings. Specifically, OTC hearing aids are not intended for people suffering from tinnitus. Realistically, however, how would we stop them? When we think about tinnitus in this bigger framework of safety, there are plenty of people living with tinnitus that do absolutely nothing. They're at risk, as well. One way of looking at it is at least if they purchased one of these devices, and if they happened to read the labeling, they would know that if they hear ringing in their ears, that they need to pursue medical care. In some ways, this could get people to do something sooner if they read those risk warnings, as opposed to now when they may do absolutely nothing.

Can you speak to the data from other countries that already have over-the-counter devices?

I don't have good data. There was a paper published out of Italy with information about over-the-counter hearing aids, and they reported information similar to our direct-to-consumer findings. Some people don't like the fit, which is going to be the most obvious thing because it's not a custom fit. Some of these devices are better than others. There is not one answer. I will say that these reports all focus on accessibility and affordability as the main issues. This is something I'll go into more detail in my upcoming talk. When you look at countries that socialize medicine (e.g., the UK where hearing aids are free), they still only have a 40% uptake on hearing aids. Clearly, it's much more than affordability, which is why I like to talk about this as just one more pathway. I think this is a pathway some people will access and it will be beneficial to them. However, to say OTC devices are going to be a cure-all would be wildly inaccurate.

Do you think that manufacturers will label OTC hearing aid products with their names, or private label?

That's a good question. First of all, I think all hearing aid manufacturers will produce OTC hearing aids. As hearing aid manufacturers, it is an additional revenue source. Additionally, they already have good standing products, so why wouldn't they? The labeling question is interesting, one which I have not thought about and I don't know the answer. There could be both advantages and disadvantages to a company being associated with OTC hearing aids.

Even though FDA is not enforcing medical clearance, if it's required by state license law, do we still need to get it?

It's absolutely critical to look at your own state rules, regulations and laws and to follow those. Although the FDA is not enforcing the medical clearance or waiver, if you have a hearing aid registration law or a state license law that requires you to have it, you must follow that. That's a good question and a very important point.

References

Abrams, H.B., Chisholm, T.H., McManus, M., & McArdle, R. (2012). Initial-fit approach versus verified prescription: Comparing self-perceived hearing aid benefit. JAAA, 23(10), 768-78. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.23.10.3.

Cox, R.M., Johnson, J.A., & Xu, J. (2014). Impact of advanced hearing aid technology on speech understanding for older listeners with mild-to-moderate, adult-onset, sensorineural hearing loss. Gerontology, 60(6), 557-68.

Humes, L.E., Rogers, S.E., Quigley, T.M., Main, A.K., Kinney, D.L., & Herring, C. (2017) The effects of service-delivery model and purchase price on hearing-aid outcomes in older adults: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. American Journal of Audiology, 26(1), 53-79.

Kochkin, S. (2014). A comparison of consumer satisfaction, subjective benefit, and quality of life changes associated with traditional and direct-mail hearing aid use. Hearing Review, 21(1), 16-26.

Kochkin, S., Dennison, L., & Jackson, L. (2014). What is your customer loyalty quotient (CLQ)? Hearing Review, 21(9), 16-21.

Leavitt, R.J., & Flexer, C. (2012, December). The importance of audibility in successful amplification of hearing loss. Hearing Review. Available at www.hearingreview.com

Further references are in the course handout.

Citation

Palmer, C. (2018, January). Signia Expert Series: Over-the-counter hearing aids - opportunity or disaster? AudiologyOnline, Article 21066. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com