Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live webinar. Download supplemental course materials.

Dr. James Hall: I have a policy that I have maintained for the past 40 years: I do not talk about topics that I am not involved with clinically. You will not hear me talk about vestibular assessment, complicated hearing aid fittings or cochlear implant programming. Today I am going to talk about tinnitus, because for the last 15 years or more I have specialized in this area.

In the late 1990s, the research on tinnitus was starting to develop, and up to that point, we did not know much about the mechanisms of tinnitus or, consequently, how to treat it. Now, we have explanations for tinnitus that arises in the auditory system, and we have several evidence-based treatment options. Over these last 15 to 16 years, my knowledge has continued to grow, and that has benefited my patients.

Every audiologist with an understanding of anatomy and physiology and who can perform basic hearing tests, even recent Au.D. students and sometimes fourth-year externs, can help most tinnitus patients. Not only can they help them, but they can usually get the patient to the point where they are not bothered by tinnitus anymore. There are going to be about 10 to 15% of patients who need more help, and these patients can be referred to a tinnitus expert. Every one of you can help tinnitus patients, no matter how distressed they are. Do not be discouraged by that. You have to maintain a positive, upbeat attitude, exude confidence, and you have to give the patient hope. If you can give the patient hope, and if they are convinced that you can help them, 99 times out of 100, you are going to help them. With that little pep talk, we are going to move right on to the list of topics.

I am going to start out with the definition of tinnitus, which will also include information on where tinnitus arises in the auditory system and why some people are bothered by tinnitus and others are not. Then I will cover the audiological assessment of tinnitus, with emphasis the audiologist’s role. The audiologist is not seeing a patient with tinnitus all by him or herself. Physicians, primarily otolaryngologists, are almost always involved. You will see that the test battery you use to evaluate most of your everyday patients, with a few modifications, can easily be adapted to patients complaining of tinnitus. Then we will talk about general management strategies that are very effective. Once the diagnosis has been made and you have verified that the tinnitus is a symptom of aging or noise-induced hearing loss, not a pathology of disease, then management very often involves counseling. I do not mean to imply that management is simple, but “general” in the sense that it does not require special devices, and it is not expensive. The general management of a typical tinnitus patient in my clinic would cost the patient about $50, aside from the actual assessment cost, which is almost always covered by insurance. These patients very often have run up bills of tens of thousands of dollars getting various assessments including MRI and vestibular tests, and still have not had any treatment for their tinnitus. Most third-party payers are more than happy to pay for the diagnosis and assessment of tinnitus, with the assumption that it will lead to a cure.

Then we are going to go beyond the general management strategies to specific treatment options. Do not feel that if you do not identify yourself as a tinnitus expert that you cannot implement these options; you certainly can. As Catherine mentioned, hearing aids are incredibly valuable in managing tinnitus. We also use combination devices, which incorporate not only amplification circuits, but also other circuits with special sounds or various types of noise. I like to use the word sound rather than noise, because noise has a negative connotation.

We have ambitious agenda today. This is a topic wherein my normal lecture is a couple of hours long or given over one-and-a-half days. This is just an overview of a topic that is broad in scope.

Tinnitus

There is no standard definition of tinnitus, but a well-accepted definition is that tinnitus is a phantom auditory perception. Let’s break down that sentence. “Phantom” means that it is not related to an external stimulus; that term is borrowed from medicine, where someone has had an arm or leg amputated, but they report that they can still feel their fingers or toes. There is neural representation for the sensory experiences that they have related the lost limb. The same is true for tinnitus. The patient has a neural representation, or activity in the brain that is related to sound, and that is why they are hearing the tinnitus. It is auditory, obviously, and it is a perception.

Some patients feel they are alone or unbelievable when they make claims about tinnitus. I start out by counseling my patients, “Based on everything you have said, I am convinced that you hear these sounds. You are perceiving them and hearing them just like you are hearing my voice. If we could do a brain scan right here my office, we could show that your brain is being activated even when there is no sound present.” This concept of a phantom auditory perception does not mean it is in their imagination; these are real perceptions. There is plenty of evidence to prove that tinnitus does exist and the activity shows up in brain scans.

This next item is critical. I will tell everyone this, including referring physicians. Tinnitus is a symptom, not a disease. There are no treatments for a symptom. There are treatments for the diseases, which give rise to symptoms. We have to remember this.

There are two important messages here. One is to first treat the disease. If a patient has Meniere’s disease and tinnitus or an acoustic neuroma and tinnitus, let's deal with the original problem. Even if a patient has sinusitis and congestion or allergies with tinnitus that is always worse at those times, let’s treat the original disease or disorder. Having said that, close to 90% of all patients with tinnitus do not have an active disease or pathology. I stress that point to patients. Most people have damage to the outer or inner hair cells. It is not a concern from a medical point of view. Keep in mind we cannot, technically, treat tinnitus. We have to treat the disease. When there is no disease, then we try to reduce the impact of tinnitus on quality of life.

What we are talking about today is bothersome tinnitus, not the kind of tinnitus that most everyone has every now and then. I have a high-pitched, ringing type of tinnitus with a complex sound. I can hear it distinctly when I concentrate on it and think consciously about it – which tends to happen when I am lecturing about tinnitus or counseling a patient with tinnitus. Earlier today, I did not notice it, and later today I will not notice it. This is the typical type of tinnitus people have, but we do not see those patients too often. Bothersome tinnitus affects quality of life. It is subjective because we cannot hear it. We cannot do any diagnostic test that proves that it is there or confirms what it sounds like. It is called subjective tinnitus because it is only perceived by the patient.

The phantom auditory perception, or subjective tinnitus, is very different from a somatosound. The word somatosound means a sound produced by the body. For example, somatosounds could be clicking sounds due to a temporomandibular joint that is out of line or the contraction of the tensor tympani muscle, or a swoosh-swoosh sound due to blood flow through an enlarged jugular vein. Those are actual sounds produced by the body that a person hears, as opposed to a phantom sound. Any patient experiencing something that resembles a somatosound must be evaluated immediately by a physician, preferably an otologist.

Types of Tinnitus

There are almost as many types of tinnitus as there are people who perceive tinnitus. We cannot know what a person is hearing. They have to come up with descriptions that represent a sound as closely as possible, but they are never an accurate description of the tinnitus. If someone said, “What does a rose smell like?” how would you describe that? There is no way to capture exactly what a sensory experience is all about because it is a perception. This is the same with tinnitus. The most common types, based on 119 patients I interviewed at Vanderbilt University when we had just opened a tinnitus center, are ringing, crickets, high-pitched tones, humming and hissing. Any of these sounds might be described by a patient; however, none of this information has any diagnostic or prognostic significance. In other words, one type of tinnitus is not worse than the other, although patients will be convinced of that. That is one misconception you need to clear up right away.

One type of sound does means that they have any particular disorder or disease. They are going to receive to a complete diagnostic assessment, and likely not have anything that needs immediate medical treatment. We are going to focus on not perceiving the tinnitus. We are not going to be worried about what type of tinnitus patients have. The type of sound does not contribute to the patient's diagnosis in any consistent way, nor is it related to how well or poorly they will do with treatment.

Tinnitus is a serious problem for 13 to15% of Americans who seek medical attention for their tinnitus. Of this group, about 2 million find the tinnitus debilitating, having a very negative impact on their quality of life. What one question would you want to pose to a patient to find out if the tinnitus was debilitating? I would ask, “Mr. Johnson, are these sounds that you are hearing in your head bothering you at night, keeping you from falling asleep or interrupting your sleep?” If Mr. Johnson says, “Yes. That is exactly what they are doing,” then you know that this person has a problem and that the tinnitus is debilitating. You need to help them. I am not saying people who are not having problems sleeping are not bothered by tinnitus, but sleep disorders are closely linked with tinnitus, and that is a problem we have to solve. Be aware that in some populations, such as the Veteran’s Administration (VA), the incidence of tinnitus is going to be much higher than the general population.

Non-helpful Advice from Physicians

Physicians never get a class in tinnitus. Having been at medical schools all my career, I know that medical students barely get an hour of lecture time on the subject. Aside from otolaryngologists, most physicians do not know much about tinnitus, which is a shame because it is a common problem. As a result, they give patients poor advice. These are five common things that patients have reported hearing from physicians: there’s nothing wrong with you; you have normal hearing; there’s nothing we can do for you; avoid being around noise; and you’ll just have to live with it. You need to start neutralizing statements that the patient might have heard from a physician, without being too critical of their family doctor.

The statement, “There is nothing wrong with you,” does not make any sense. Why would a person take a day off from work and spend money out of their own pocket to see a doctor if there was nothing wrong with them? They are not paying the doctor a social visit.

“You have normal hearing” means, “I am talking to you and you seem to be understanding what I am saying.” That never means they had a completely normal audiologic assessment including otoacoustic emissions (OAEs). In fact, almost every patient you meet with tinnitus will have a cochlear problem that is detected by OAEs and very often the audiogram. You have clarify and say to the patient, “Dr. Jones meant you do not need a hearing aid,” or “Dr. Jones meant that he did not need to do any medical treatment for hearing loss, but you do, in fact, have a problem with your ears, which is where the tinnitus is coming from.” The news that a patient has something wrong with their ears is comforting to most patients.

“There is nothing we can do for you” is an ignorant and irresponsible response to a patient’s complaint. Take every opportunity you have to educate family doctors, whether you are in a VA setting, hospital setting or in a community practice. Educate family physicians and general physicians about tinnitus. All you need to tell them is that we do know a lot about it, and there is a great deal of research on tinnitus. We know where it comes from and how to treat it. Ask physicians to refer these patients to us.

“Avoid being around noises.” This statement is usually directed toward to a male who has been exposing his ears and has a noise-induced hearing loss. The doctor means, “Stop damaging your ears.” The patient usually says, “Ok, so if I go to quiet places, maybe this tinnitus will disappear.” That, however, is the worst thing to do. One of our general management strategies is to remind patients to always be around soft, pleasant, consistent sound. Avoid quiet places.

“You will have to learn to live with it” is one of the most negative things you can say to a patient who is troubled by tinnitus and has not been able to learn to live with it. That is why they came to you in the first place.

Patient Complaints and Characteristics

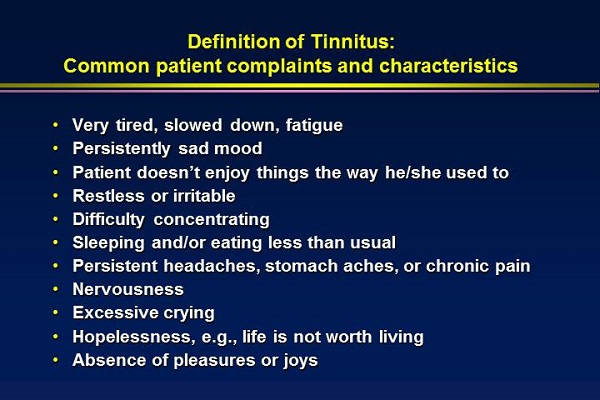

Tinnitus has incredible psychosocial ramifications. It affects a person's general health and how they feel about themselves. Figure 1 lists common patient complaints; some people have all of these characteristics, and certainly every patient has at least some of them. You will see grown men crying in your office. You will see people who would have always been upbeat with a positive attitude exude a sense of hopelessness. They do not want to live life anymore. Their spouse will tell you that the patient is not the same person they married. They are irritable, grumpy, and shouting at the children to be quiet or go away. These psychosocial problems are very serious.

Figure 1. Common complaints and characteristics of tinnitus patients. (Click on image for larger view)

Amazingly, you can immediately diminish these issues if you address the impact of tinnitus on quality of life. I will often get the patient to realize that I know what they are going through by saying, “Mr. Johnson, I bet you have had significant problems concentrating at work or reading, and Mrs. Johnson is probably a little tired of the way you are snapping at her. You are probably frustrated with yourself.” They will say, “How did you know?” When you begin to empathize with a patient, they begin to trust you and they will agree to do whatever you recommend.

Jack Vernon (1922-2010) focused much of his research attention on tinnitus and brought it out of the shadows. He was one of the co-founders of the American Tinnitus Association. He began to develop theories about tinnitus that have since been proven. He dedicated much of his work to helping people understand the serious impact that tinnitus has on daily life and that tinnitus patients are underserved.

Anatomy and Physiology

You need to understand the mechanism of tinnitus to manage patients with tinnitus. You need to be able answer questions with confidence. Understanding the mechanisms of tinnitus will develop your confidence in managing patients.

The origin of tinnitus is almost always in the cochlea. This is well-researched in both animals and humans. When the cochlea is damaged, that is called peripheral deafferentation. The connection between the inner hair cells and the auditory nerve fibers has been disrupted, resulting in a loss of input to the auditory system. Interestingly, the auditory system reacts by releasing excessive amounts of excitatory neurotransmitters to overcome the reduction in stimulation of the cochlea due to cochlear damage. This over-excitation of the nervous system begins to become entrenched, ingrained, and represented in certain areas of the brain, resulting in a person hearing sound when there is not a sound. The auditory nerve must be involved because it is connecting the cochlea to the brain. In patients with tinnitus, you will often see a disruption of the normal resting potential in the eighth nerve.

The middle ear does not cause tinnitus, but I have seen dozens of patients who clearly attribute the perception of tinnitus to a history of clinical findings within the middle ear. For example, let’s say you are flying and everything is fine. When you are descending, you cannot clear your ears when you land. You may even have a cold or allergies on top of that. The next thing you know, you hear tinnitus. However, as your ears begin to pop and clear, the tinnitus goes away. You are basically hearing a sound that is always there, but there is less external sound from the environment to mask out the tinnitus of which you are normally unaware. The cochlea is almost always the origin of tinnitus. I will present some guidelines for how we, as audiologists, evaluate tinnitus.

It is important to focus on every physiological aspect that encompasses the auditory system. Make sure the middle ear is clear and that there are not any problems with pressure in the mastoid air cells surrounding the middle ear. Focus on the cochlea by routinely testing OAEs when evaluating patients with tinnitus.

A person is not going to know they have tinnitus unless the brain is activated, and they may not be aware of tinnitus if it is only the brainstem that is activated. Research is clearly showing that the cochlear nucleus can be reorganized, all the way up to the inferior colliculus. That can be documented with very specific brain imaging by MRI. Once the activation reaches the auditory cortex, the person will perceive the sound. There is a release of excessive amounts of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate in the brain, which is what is excessively activating the brain.

We believe the limbic system and the autonomic nervous system are non-traditional auditory regions of the brain that must be involved in people with bothersome tinnitus. There are millions of people with cochlear damage and hearing loss. Some may occasionally hear tinnitus that is not offensive enough for them to make an appointment with a doctor. It is the patients with limbic system or autonomic nervous system involvement who are bothered by the tinnitus. The emotional response to the sound of tinnitus is an activation of the limbic system. That is why patients cry in your office when they are talking about their tinnitus. Music is a great analogy of how the limbic system is tied closely to the auditory system. Music can make you feel happy or sad and bring about deep emotions. Likewise, music can be irritating if it is boring or cacophonous.

The autonomic nervous system is very complex. It controls homeostasis in our body. It also is involved in the fight or flight response to danger. Some sounds can make you very relaxed, and other sounds startle or scare you. Some sounds are danger signals, such as emergency sirens or a dog growling. It is very important for your patient with tinnitus to understand what is going on with them. Their emotional reaction to tinnitus is very natural with physiological underpinnings; it cannot be prevented and should not be perceived as a psychological weakness. Their experience is typical of someone who hears a sound and does not know what it means. In fact, one would be foolish to ignore the sound without exploring what it means. It could be something serious. When patients are informed about the anatomy and physiology of their auditory system, they begin to stop worrying about the tinnitus and they begin to feel less fearful.

There is clear evidence that in some patients the efferent or inhibitory system is not functioning well. We have a cochlea and an afferent auditory system that is overreacting to sound. Perhaps some of the sound therapy that is so effective in tinnitus treatment is helping to develop the efferent function that should have been there all along. My recommendations for publications that address the auditory mechanism can be found in your handout.

Another expert in the field of tinnitus is Pawel Jastreboff. You might have heard him lecture at Audiology NOW or attended one of his intense 3-day workshops. I would recommend a workshop for anybody who wants to develop an expertise in tinnitus management. Jastreboff developed a theory which is now called the Neurophysiological Model of Tinnitus, which is the model I have just explained to you – that there is neural representation to tinnitus along with involvement of the limbic and autonomic nervous systems. The question of why some people hear and react to tinnitus differently evolved into a logical way to approach tinnitus management. Jastreboff, Gray and Gold (1996) developed a formal technique called Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT). I use the concepts and general principles of TRT with every patient I see.

When people start to respond emotionally, we know the limbic system has become involved. The evidence clearly shows activation of the limbic system in people with bothersome tinnitus. When a patient is debilitated by tinnitus, they are responding at the level of the autonomic nervous system. It upsets them. They may have panic attacks, elevated blood pressure, or break out in a sweat. They may avoid certain situations where they are afraid the tinnitus will become activated. We have to sever or minimize the connections within the brain that activate the tinnitus.

Research documents that these parts of the brain are involved. The earliest of articles was published by Lockwood and colleagues in 1998, but researcher after researcher has shown that the Neurophysiological Model of Tinnitus is true.

Audiological Assessment

When assessing a patient with tinnitus, we begin with a brief consultation, a full diagnostic audiological assessment, a tinnitus evaluation, and then counseling in more detail. We decide whether we need to move ahead with hearing aids or combination devices or other forms of treatment. Perhaps we just give the patient some accurate information and no further services are needed.

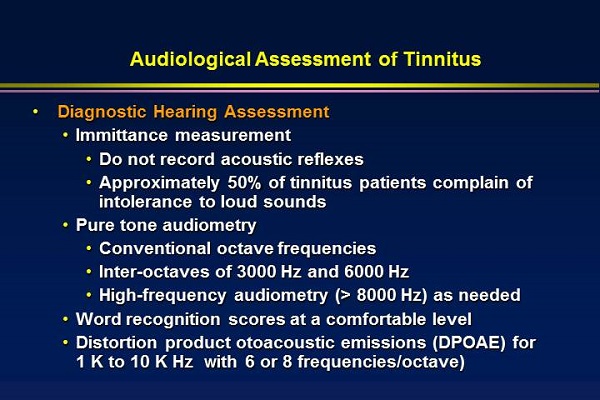

The complete audiological assessment is listed in Figure 2. I always begin with tympanometry, but I do not perform acoustic reflexes, as many of these patients have hyperacusis and are very intolerant of loud sound. There is nothing to be gained by recording acoustic reflexes, and you might aggravate the patient's tinnitus or encourage a lawsuit. Perform pure-tone audiometry, including inter-octave frequencies; you will want to have extended high-frequency capability on one of your audiometers. Every now and then you will run into a patient with high-frequency tinnitus that needs to be evaluated.

Figure 2. Audiological assessment of tinnitus. (Click on image for larger view)

Word recognition should be tested at a comfortable level. If they have already had a full audiological assessment, I do not often repeat this testing. I am interested in comfortable loudness scores. Next, I perform OAEs. Different audiologists place different weight on OAEs as part of the tinnitus assessment, but they are critical. That is the best way to document whether or not the delicate outer hair cells are functioning properly. I go out of my way to emphasize the OAEs during counseling and what they mean. If there is damage to the cochlea, you can almost be certain that that is where the tinnitus is generated. Then I show them the DPOAE findings. If their tinnitus is valid, the pitch of the tinnitus will almost always match the frequency region where the DPOAEs are most abnormal.

When you look at the percentage of tinnitus patients with normal findings, you may find patients with normal audiograms, but you almost never find patients with totally normal OAEs. The OAEs will reveal cochlear dysfunction underlying the tinnitus that may not be detected with the audiogram.

There are several audiological tinnitus assessments you can use in your evaluation; we do not have time to go through each one in detail today. The first thing is to find the threshold for broadband noise in each ear; that may be much better than the pure-tone hearing loss. The white noise often reflects their very best hearing somewhere, often in the low frequencies. That finding will be important later when we determine how we are going to treat them with soft, relaxing background sound.

Next, match the pitch of the tinnitus as closely as you can; do not make a big deal about this with the patient. It has very little, if any, diagnostic information. All we want to do is estimate whether it is low frequency, mid frequency, or high frequency.

Then we estimate the loudness of the tinnitus. For example, let’s say the frequency of the tinnitus is 3000 Hz; then we go back and find threshold for 3000 Hz using 2 dB steps. This person’s threshold for 3000 Hz is exactly 30 dB on the audiogram, so I will start down around 28 or 26 dB and gradually increase the intensity, presenting the sound for 5 or 6 seconds. I will say, “Do you hear anything?” They may say, “I think so.” Then I ask, “Is that about the same loudness of the sounds in your ears, or should I go a little higher or a little lower?” Ninety-nine percent of patients, according to recent research, will match the loudness of their tinnitus within 15 dB of their audiogram. It is not uncommon for people to match the loudness of the tinnitus to 1 or 2 dB above the audiogram. This makes me very excited and optimistic for the patient. When I tell them that their tinnitus is soft like a pin drop and that we probably will not have any trouble getting their brain to no longer hear it, sometimes they do not believe me. They say, “But it is so loud. I cannot hear anything else.” I go into an analogy about a drippy faucet to give them the idea that if their brain does not think the sound is interesting or meaningful, it will immediately start ignoring it.

The next step is to determine how much noise is required to mask the tinnitus or break up the neural representation. For this test, I will tell the patient, “You are going to hear some rushing water noise in either ear. Tell me when you are not sure you are hearing the tinnitus anymore.” Very often I will be getting up to sounds of 10 to 15 dB, particularly in a person with fairly good hearing, and they will start saying they are not sure they are hearing the tinnitus anymore. That is amazing, because then I know that minimal exposure every day to soft background sound will probably keep them from hearing their tinnitus. Sometimes putting a low amount of sound into one ear will keep the patient from hearing the tinnitus in the opposite ear. That is a form of central masking, but now we know that that noise is breaking up the neural representation of tinnitus.

Lastly, I do not do loudness discomfort levels (LDLs) on every patient, but I do them on most patients. I always do them if the patient is complaining of loud sounds bothering them or if they report decreased tolerance to sound.

There are guidelines for tinnitus assessment put out by AAA, which can be found on their Web site here. They have assembled a new task force, so we can expect to see updated guidelines sometime in the next year or so. One of the requirements for tinnitus assessment is some type of validated inventory, which I strongly encourage. It could be any inventory that has been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

I like the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (Newman, Jacobson, & Spitzer, 1996) because it is quick, easy for patients and easy for me. There are 25 items. In answer to each question, the patient circles yes, maybe, or no, and then you score it: 4 for yes, 2 for maybe, and 0 for no. Twelve of the items address how the tinnitus affects day-to-day function, eight items address emotional status, and five items are catastrophic subscale items, which address quality of life and debilitation of the tinnitus. A score of 100 is the most undesirable score because it means the impact of tinnitus is overwhelming. A score of zero would mean that there is no tinnitus at all. Most scores are somewhere between 50 and 80. Some people categorize scores as mild, moderate or severe tinnitus. I avoid those classifications as they imply that one category of tinnitus is harder to treat that another or is more likely to be “permanent.” No tinnitus is permanent. I will tell patients that it may be long-standing or chronic. This score helps you determine the management strategy and how you are going to treat the patient and document benefits of treatment.

General Management Strategies

Counseling based on information from the diagnostic tests and other information you have gathered is critical. There is nothing more important when it comes to managing tinnitus patients. Be prepared for any possible question a patient may ask. I had a conversation with a patient that sounded like this: “My family doctor said I am going to lose my hearing because of the tinnitus. If I lose my hearing, I will lose my job. I won’t be able to feed my children and my wife.” I replied, “Hold everything. You are not going to lose your hearing. I have not seen anything in your hearing test results that makes me think you are going to lose your hearing.” Dispel those kinds of myths. Give the patient accurate information. Look them in the eye and give them straight answers.

Rank the tinnitus from 0 to 10, with 10 being “my life is ruined.” Most patients will be between six and eight. Also rank hyperacusis and hearing loss. The patient may think that they cannot hear because of their tinnitus, but in fact, it is because they have a moderate to severe hearing loss. Kindly put things in perspective, and that will help you with treatment decisions. Always give the patient practical information, such as what environments to engage or avoid. When you treat the patient with empathy, compassion and understanding, patients will be so appreciative of you and rave about your services.

Give the patient all the knowledge they can handle. They should not be scanning the Internet looking for answers. Give them the information you want them to have. I will always give them an article that I wrote for the American Tinnitus Association’s journal, Tinnitus Today, as a nice overview of how I treat patients (Hall, 2004). It is upbeat and very easy for patients to understand. Keep brochures from AAA or from the American Tinnitus Association in your counseling room and dispense them to patients. Go through them with patients and their significant others to make sure they read them. The more both partners understand the tinnitus, the better their outcome.

Make sure that the patient has seen a good otologist to rule out the many diseases and disorders, some severe, that can be associated with tinnitus. Review the patient's history, including their medications, but do not make a big deal out of this. Often, drugs that note tinnitus as a side effect are the result of one person mentioning it to the drug company during the clinical trial. The link is often poor between tinnitus and these drugs. If a patient is taking a large dose of aspirin, you can tell them that it can be associated with tinnitus. If a patient is taking Lipitor for cholesterol or maybe Xanax to reduce anxiety due to the tinnitus, you can tell them that those sometimes can cause tinnitus. When possible, we want the patient not to be taking drugs that cause tinnitus. This is more for the family doctor to decide, however; not you.

Specific Management Strategies

The best treatment option is to provide whatever the patient needs, but no more. That is the basic premise behind the tinnitus management strategy developed by James Henry and colleagues at the VA National Center for Rehabilitative Audiology Research (NCRAR) in Portland, Oregon. It is called Progressive Tinnitus Management. Their books on tinnitus and tinnitus management should be added to your library. How to Manage Your Tinnitus is a step-by-step workbook for patients (Henry, Zaugg, Myers, & Kendall, 2010a). They also have a book on Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (Henry, Trune, Robb, & Jastreboff, 2007). They recommend to do whatever it takes to treat the patient, from brief counseling all the way to extended form of treatment like TRT.

Melatonin reduces tinnitus and also enhances restful sleep. I recommend it, but always tell the patient to check with their family doctor to be on the safe side. It is an over-the-counter substance, not a sleeping pill. We all have melatonin in our blood and the research supports using it (Piccirillo, 2007; Neri, et al., 2009). In fact, some patients feel comforted by taking a pill for their tinnitus. It feels like they are doing something positive to help themselves.

Sound enrichment as a management strategy involves using inexpensive sound devices, such as those pictured in Figure 3. These can range from desktop devices to sound pillows, in case the patient complains that the desktop sound system is affecting their spouse.

Figure 3. Sound enrichment devices for the management of tinnitus; desktop sound machine (left) and sound pillow (right). (Click on image for larger view)

Counseling has a measurable effect on tinnitus (Hall & Haynes, 2001). We have already discussed counseling, so, for the sake of time, I will allow you to refer back and read that topic again. Fortunately, in this day and age, we have an array of tinnitus devices that are coupled with hearing aids. You can use one of these devices with a tinnitus component with or without any amplification. If the patient has any degree of hearing loss whatsoever, open-fit hearing aids are great option. The use of amplified sound will minimize tinnitus, coupled with some counseling; that may be all the patient needs. You can also include a sound-generation circuit within the hearing aid. There are many different options available from different hearing aid manufacturers. In fact, many times when you buy a high-end hearing aid, you are getting all the tinnitus features automatically. You can offer the patient a hearing aid to begin with, and then be able to incorporate some of the other programs if tinnitus is still interfering with their daily life.

TRT was developed almost 20 years ago (Jastreboff, Gray, & Gold, 1996) and is an evidence-based treatment option. We are taking advantage of the brain's plasticity to retrain it to no longer hear the tinnitus. The research on this is quite overwhelming and has included subjects from the general population, the military and the VA. Your handout lists numerous studies for your review.

Neuromonics is another evidence-based treatment option. It is not necessary for everyone, but for people who are significantly bothered by tinnitus, especially in the frequency region above 8000 Hz. Most sound devices do not extend to that bandwidth, but the Bang and Olufsen earphones coupled with the Neuromonics device do provide sound output well above 8000 Hz. Neuromonics is also a great system for people where the typical sound therapy intensifies tinnitus or for people who have decreased tolerance to loud sounds.

There is no magic pill for tinnitus. Any tinnitus treatment that you see advertising tablets or drops is not legitimate. If you research those claims, you will find there is no evidence to support them. There is a treatment for tinnitus; it just does not come in the form of tablets.

Summary

Stress to patients that tinnitus is a symptom, not a disease. You have to complete a thorough audiological and medical evaluation and tinnitus assessment. Over 80% of patients who are given counseling, surround themselves by pleasant sound, and take perhaps a little melatonin can receive significant relief from their tinnitus. If the tinnitus persists beyond four to six weeks, then there are very effective evidence-based tinnitus treatment strategies that are available. I stress that to patients at the get-go so they do not give up hope. They know no matter what happens, we will take care of their tinnitus. Remember that all patients with tinnitus should have hope.

Question & Answer

What is the diagnostic significance of unilateral low-frequency tinnitus and bilateral high-frequency tinnitus?

Unilateral low-frequency tinnitus is worrisome. Even without an asymmetry in hearing, it is worrisome. That report immediately makes me think of retrocochlear dysfunction, perhaps a vestibular Schwannoma. Anyone with unilateral tinnitus may not truly have unilateral tinnitus, but it may be, in truth, louder in one ear than the other. It needs to be thoroughly evaluated by an otologist.

Unilateral tinnitus is one of the red flags that the American Academy of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery notes is cause for referral of a patient for an MRI or to an otologist. Medical assessment is necessary. Bilateral high-frequency tinnitus is by far the most common kind. By high-frequency I mean somewhere between 3000 and 6000 Hz. It is almost always linked to a high-frequency sensory hearing loss.

Those are two very different types of tinnitus. The prognosis of unilateral tinnitus is difficult to determine, especially low-frequency tinnitus. There may be a medical treatment for it, or it may go away. For the bilateral high-frequency tinnitus, I would stress to a patient that this is the most common type of tinnitus. We have more experience treating it than any other type tinnitus, and that makes me very optimistic that we will be able help them.

How do you feel about giving the patient a tinnitus therapy volume control where the patient can control the volume of the noise or the therapy signal they are using?

I have no problem with putting the patient in charge with a volume control, but I will emphasize to them that the goal is not to mask the tinnitus entirely. Jastreboff and others have shown if you totally cover the tinnitus, it will still be there when you take the masking away. According to the neurophysiological theory, in order to retrain the brain, you have to get the patient to control the background level of sound so that it mixes in with the tinnitus. The patient should barely hear the tinnitus so that the brain perceives the tinnitus and the other sounds equally. Jastreboff calls this the mixing point. As the patient keeps hearing a consistent sound that has no meaning, they will habituate to it. This is like you habituating to an air conditioner or a clock ticking on the wall. After a while, you do not know there is sound there at all. At that point, the patient will begin to notice that there are times during the day where they are not aware of the tinnitus.

There are some strategies for tinnitus management, including Neuromonics, where it is not bad to let the patient use masking to get rid of the tinnitus for an hour or two. But in terms of long-term strategy, I want to make sure that they are keeping the tinnitus barely perceptible.

I would think that having control of that volume would be useful for those individuals who have tinnitus that fluctuates from day to day or hour to hour, as mine did. Do you agree?

Yes, I do. However, the danger is that some people micromanage their tinnitus. Some people keep a journal; I tell people no more journals and no more focusing on tinnitus minute to minute. You are exactly right, however. The intensity of the tinnitus will shift from time to time and it gives them some control. It gives them confidence that nothing is going to get out of hand, but you have to advise them appropriately. This is the same with sound therapy.

For those hearing care professionals who have never formally treated tinnitus patients, could you give some guidance as to how to choose from one of the many programs?

I would be happy to. I take a very direct role with the patient. Jastreboff talks about directive counseling. Patients come to us as professionals, and we have to take it upon ourselves to be very specific and clear. Number one, do not recommend anything for treating tinnitus unless it is evidence-based. If they say, “Dr. Hall, I heard acupuncture and hypnosis might help my tinnitus or hypnosis.” I will say, “You are welcome do the research, but I have already done it. Acupuncture does not consistently help tinnitus. There are no systematic studies in the peer-reviewed literature that show the benefit of acupuncture or hypnosis and low-level laser therapy. The reason I am telling you this is that I do not want you to spend your money on something and get more disappointed that it did not help your tinnitus.” Present the research and review it with them.

There are many other factors to take into consideration. My philosophy is to do the least I need to do. Cost enters into the equation for many patients, and then we also have to consider the impact of tinnitus on quality of life. Some of the treatment options go beyond audiology. If, after six to eight weeks of generic therapy and perhaps some specific therapy like open-fit hearing aids with dedicated programs for tinnitus, the patient is still distressed and still not getting sleep and the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory score is still high, they need to see a licensed psychologist for a technique which is called cognitive behavioral therapy (CBD). I explain that to them. It is one of the most effective treatments for tinnitus. It will get the patient to look at their tinnitus in a different way. You have to tailor the treatment to the patient, but within certain guidelines. Whatever you recommend must be evidence-based.

Have you had any experience with the Serenade device by SoundCure?

I have not used the SoundCure device or approach, but I have researched it. You do not have to be an expert in every technique. You want to have a repertoire of things with which you are comfortable and can use with confidence. I tend to be aggressive in my management approach, but when it comes to utilizing new techniques for tinnitus treatment, I am a bit more conservative. I like to hear someone present about it at a meeting that is not sponsored by the company, and then I like to see a peer-reviewed journal article or two. I might even call a colleague and ask if they have had any experience with the device and their opinion. The short answer to your question is no, but that does not mean I do not think it has value. I do not know enough to comment one way or the other.

Do you find that most psychologists have knowledge about CBT or do you need to search for a psychologist that specializes in this? Also is covered by a third-party payer?

That is a good question. You do have an obligation to know something about the specialist to whom you are referring the patient. You want make sure that specialist is not going to do any harm. Every town will have psychologists; if you research online, you will see CBT cited as one of their areas of expertise, if it is one. I would recommend calling them and explaining what you do and that you work with patients who are bothered by tinnitus. Ask to talk to the psychologist personally about seeing some of your patients. If they have never seen anyone with tinnitus, do not necessarily rule them out. The main thing is that they understand CBT and then they can learn about how that works with tinnitus.

There are also some self-help guides. I have had indigent patients who needed CBT but could not afford or find services. There are online options, or you can purchase some of the self-help books and loan them out to patients so they can work their way through CBT. The Progressive Tinnitus Management book by Jim Henry (2010b) has quite a bit of information on CBT.

References

Hall, J. W. (2004). An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Tinnitus Today, December, 14-16.

Hall, J., & Haynes, D. (2001). Audiologic assessment and consultation of the tinnitus patient. Seminars in Hearing, 22(1), 37.

Henry, J. A., Trune, D. R., Robb, M. J. A., & Jastreboff, P. J. (2007). Tinnitus retraining therapy: patient counseling guide. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T., Myers, P., & Kendall, C. (2010a). How to manage your tinnitus: a step-by-step workbook. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T., Myers, P., & Kendall, C. (2010b). Progressive tinnitus management: clinical handbook for audiologists. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Jastreboff, P. J., Gray, W. C., & Gold, S. L. (1996). Neurophysiological approach to tinnitus patients. American Journal of Otology, 17, 236-240.

Lockwood, A. H., Salvi, R. J., Coad, B. A., Towsley, M. L., Wack, D. S., & Murphy, B. W. (1998). The functional neuroanatomy of tinnitus: Evidence for limbic system links and neural plasticity. Neurology, 50, 114-120.

Neri, G., De Stefano, A., Baffa, C., Kulamarva, G., Di Giovanni, P., et al. (2007). Treatment of central and sensorineural tinnitus with orally administered Melatonin and Sulodexide: personal experience from a randomized controlled study. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica, 29(2), 86-91.

Newman, C. W., Jacobson, G. P., & Spitzer, J. B. (1996). Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery, 122(2), 143-148.

Piccirillo, J. F. (2007). Melatonin. Progress in Brain Research, 166, 331-333.

Cite this content as:

Hall, J. W. (2013, September). Siemens expert series: Evidence-based management of troublesome tinnitus - practical guidelines for the practicing professional. AudiologyOnline, Article 12166. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com