Introduction

The purpose of this article is to examine some of the practical issues involved in working with clients with severe to profound hearing loss acquired early in life following normal language acquisition. This group of clients represents a relatively small percentage of most clinicians’ caseloads, but their needs are more complex and may demand higher levels of innovative ‘outside-the-box’ solutions. This article draws on my unique personal and professional experiences. I suffered a severe-to-profound hearing loss during a near-fatal attack of Meningitis at the age of eight. Driven by years of social and educational frustration, I undertook studies in psychology, rehabilitation, audiology, and eventually settled in private practice as a hearing rehabilitation specialist and owner of two hearing aid clinics. Here I will review eight key strategies for clinicians developed from my personal and professional experiences. My hope is that other professionals faced with helping clients from this high-needs group might have a few more tips and tools to enhance their clients’ journeys towards optimal communication function.

Preamble 1: Restoring hearing is not the same thing as restoring communication function

If we assume that the purpose of hearing rehabilitation is to help clients optimize their communication function, then it is important to recognize that restoring communication function is not the same thing as restoring ability to hear (Weir, 2009). People with normal hearing can exhibit poor communication function even though they can hear perfectly well. Effective communication function depends on a balanced mix of effective listening and responding skills (receptive and expressive communication abilities) and is therefore a primary skill or tool in the quest for successful social engagement. Any impedance to the frequency, quantity, or quality of interpersonal communication can have a significant impact on the quality and stability of social engagement. If left untreated long enough, it can also have a damaging impact on mental health. Whether caused by a hearing loss, speech impediment, language barrier, anti-social behavior, over-reliance on digital versus face-to-face interpersonal interaction, or a destructive personal communication habit, the result is a damaging impact on the ability to engage socially with other people in mutually satisfying, relationship-healthy ways. Consequently, remedial audiological or rehabilitative intervention strategies that focus solely on optimizing receptive hearing ability, without considering a client’s expressive communication abilities, will generally fall short of optimizing communication function, even though they may succeed in optimizing hearing ability. Most audiology researchers focus somewhat narrowly on restoring damaged hearing, as if doing so will automatically enable clients to re-engage socially. Of course, for people with mild to moderate hearing loss, this assumption may be at least partially true. When the loss is in the severe to profound category, and also long-standing, the collateral damage to inter-personal communication skills, personality, self-image and ability to correctly interpret social norms can be significant. In these cases, much more individually-designed remedial action may be needed to assist clients to optimize their communication function skills as tools to re-establish healthy social engagement. The need for professional expertise outside the traditional realm of audiology becomes painfully evident when trying to assist people with severe to profound hearing loss acquired post-lingually. Unfortunately, patients with these levels of hearing loss frustratingly discover, all too frequently, that most audiology professionals are only equipped to deal with the restoration of hearing. This approach is only one paradigm in the overall picture of communication dysfunction.

Preamble 2: Identity and needs overlaps with the pre-lingually deaf

Most people with acquired severe to profound hearing losses identify themselves as part of the mainstream normal-hearing community, rather than as part of the deaf signing community, although their levels of hearing loss more closely align with the deaf signing community. However, audiology or rehabilitation professionals attempting to help this special needs client group need to be aware that there are many overlaps with the communicative behaviors and needs of those with pre-lingual profound deafness that should be taken into account when designing rehabilitation plans. This article attempts to address some of those needs.

Preamble 3: Unique professional skill set needed to address special needs of this client group

If one need stands out above all others in this discussion, it is a need for the involvement of professional counsellors or psychologists trained in the study of didactic analysis, verbal communication, and effective speaking strategies, who will undertake additional studies into the effects of severe hearing loss on functional communication skills. Ultimately, these professionals would be best suited to research and develop effective remedial strategies and professional tool kits (in cooperation with audiologists) to help professionals and families to address these neglected needs.

Features and Strategies

What follows is a series of common features of this client group and some helpful strategies developed based upon my personal and professional experience with post-lingual severe hearing loss.

Reliance Upon Vision as a Key Communication Conduit

Both clients who are pre-lingually deaf and those who are post-lingually severely hearing impaired are vitally dependent upon a clear view of the speaker's face and lips during conversation. Audibility across the full speech spectrum with this degree of loss is usually impossible even with amplification. Therefore, visual information from facial expressions and body language are a far more critical conduit of information than for people with lesser levels of hearing loss.

Strategy - reinforcing visual input and clear speech. All hearing professionals should become fully aware, early in their training, that clear speech and visual input are important for all clients with hearing loss. It can be easy to forget, or to mention in passing during a hearing aid fitting. However, it is critical to practice this behavior in all client interactions by always facing clients and using clear speech, without exaggerated lip movements. Male practitioners should be clean shaven where culturally acceptable, or at least ensure that their complete lips are not obscured in any way by facial hair, especially the corners. It is amazing how many lip-reading cues can be destroyed by this one factor. Also keep hands and objects away from the mouth while speaking.

Use of Sign Language

It is not unusual for post-lingual severely hearing-impaired people to have some degree of fluency in sign language, especially if their hearing loss occurred during childhood. It is possible they have been exposed to it at school or in social activities involving sign language users. There are some notable exceptions to this, namely children who have been educated in strict "oral only" environments where use of sign language was forbidden. Where there is fluency in signing, it is very helpful as a supplementary aid to communicative input in difficult listening environments. Sign fluency is more likely to be rare among late-deafened patients.

Strategy - Keep options open. Fluency with sign language can be helpful when working with profoundly hearing impaired clients who are familiar and comfortable with using it as a supplement to their audition. But it can be a sensitive matter that must be approached with care. As a general rule, although I am fluent with signing, I will not use it unless it becomes obvious that verbal communication isn’t working and then I will first ask, in both sign and speech, (total communication method) if they understand signs and would like me to use it to supplement my speech. A hint that sign language might have been part of their cultural environment can be the presence of a typical “deaf voice” indicating long-standing profound hearing loss. But this isn’t always a reliable indicator. Some deafened people, such as those raised or educated in an “oral only” environment where the use of sign language was forbidden, may have an aversion to its use. There is a complex and heated history behind the “oral vs sign” debate, and it is wise to always respect the client’s preferred communication method. If verbal communication methods simply fail to work and sign language isn’t an option, then the easiest thing to do is to open up a blank Word document on your computer screen and use this to type your questions/statements and have the client answer verbally.

Delays in Educational Development

If the hearing loss has occurred during childhood or very early adulthood, delays in educational development could have occurred due to iniquities in access to classroom presentations and audio-visual materials. This was still very common as recently as 10 to 15 years ago.

It is less common today where equal opportunity or anti-discrimination legislation (among other factors) influence access in educational institutions. The impact of educational delays can be profound for any child. It may produce a deep sense of injustice and resentment and even a fear of further educational or learning experiences. These feelings can translate into a low tolerance for ambiguity in adulthood that in turn, can negatively impact social attitudes and inter-personal communication strategies.

Strategy - recommend vocational guidance. Clients who have suffered educational delays due to their hearing loss may benefit from some specialised vocational guidance assistance. Expressing an interest in the clients’ overall welfare by asking questions about how their hearing loss impacts their family and work life, can trigger a revealing discussion that brings any unmet needs to the surface, particularly in regard to the need for specialised technological assistance beyond hearing aids in the workplace or classroom. Older clients who may have missed out on the benefits of equal opportunity legislation in educational settings, and are interested enough to explore opportunities again, might benefit from a referral to a specialized disability counsellor at a nearby educational facility. Making an initial contact with the counsellor on behalf of the client when appropriate and offering your expertise to help ensure technological interface needs can be met, can be a valuable contribution to your client’s rehabilitation and further education potential.

Delays to Social Development and Effective Communication Skills

When a mild or moderate hearing loss occurs, it is often the impact on relationships and social function that prompts a person to seek professional help. When the loss is in the severe/profound category, particularly if the onset occurred at a young age, the social impacts are far more severe and significant. An inability to fully participate in social functions, especially during the developmental years, can effect personality and social engagement. The resulting social isolation is very similar to the experience of new immigrants, not yet fluent in their host country’s language, who find themselves starved of meaningful communication with all except members of their own cultural language group. Just as inappropriate responses due to language unfamiliarity can result in social exclusion and isolation, so also do inappropriate responses due to mishearing or misunderstanding conversation within one’s own language group. How a severely hearing impaired person responds when they are uncertain what was said or when they experience communication breakdowns, determines to a very large extent how well they manage to integrate in social or work situations. Thus expressive communication skills, rather than degrees of hearing loss, are more significant determinates of an individual’s “communication diet” and social integration (Weir, 2009).

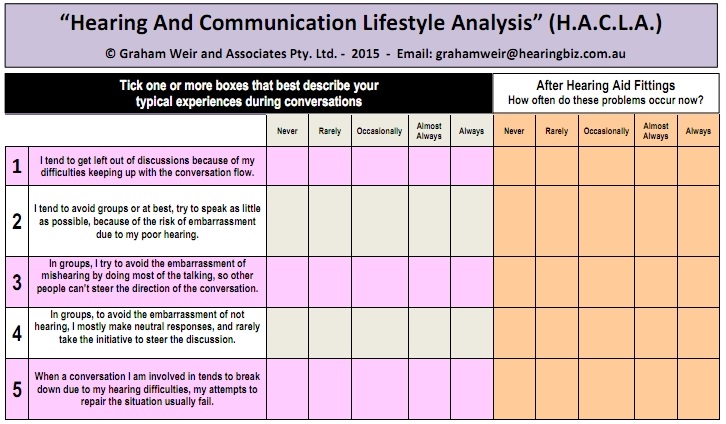

Strategy - remedial communication therapy. Hearing professionals can be instrumental in identifying the need for remedial communication therapy as an adjunct to hearing aid and assistive devices training. To help identify the existence of such needs, this author has devised four questions targeting communication behavior that can be easily integrated into a clinic’s existing intake questionnaire (Figure 1). Designed to be completed before and after hearing aid and rehabilitation services are delivered, changes in responses to each of the five scenarios assist the hearing professional to identify the specific type of unhelpful communication behaviours to be targeted with communication skills training. If a specialist who can teach effective conversational strategies can’t be found, referral to a self-help group may be the best resource. Even if such groups don’t conduct formal courses in effective conversational strategies for hearing-impaired people, their social meetings can be highly effective at modelling compensative communicative behaviours in an understanding and comfortable environment. Helping clients to improve their “communication diet” doesn’t necessarily need to involve formal sessions with a specialized trainer. Informal association with effective and sympathetic role models can sometimes be all that is needed to achieve a satisfactory transfer of communicative skills.

Figure 1. Suggested questionnaire design for identifying potentially destructive, expressive communication behaviors. Question 1 targets the degree of social isolation experienced; Question 2 targets the extent of passive communicative behaviors; Question 3 targets the extent of aggressive communicative behaviors; Question 4 targets the extent of neutral or non-committal behaviors and Question 5 targets the degree of success with the clients’ existing conversational repair strategies.

Environmental Barriers to Communicative Interaction

People with normal hearing or even mild hearing loss can usually communicate satisfactorily in a variety of spatial layouts and acoustic environments, such as restaurants or conferences. without the need to change seating positions in order to see speakers’ faces and minimizing acoustic interference. People with acquired severe/profound hearing losses find these types of settings very difficult to communicate in, even when wearing hearing aids. Multiple strategies such as changing seating positions to see speakers' faces, minimizing acoustic interference, and assistive technology may be needed. For people with a history of using passive compensation strategies, such as bluffing or avoidance, learning new assertive strategies to effectively navigate these difficult and complex listening environments can be difficult.

Strategy - Three-pronged approach. Clinicians must be knowledgeable of how acoustic conditions can degrade speech reception for clients with severe to profound losses. Remedial approaches can be three-pronged: 1) Counsel the client regarding expectations in difficult acoustic conditions. (2) Recommend hearing aids with wireless accessories and educate the client about the potential of these devices to minimize negative experiences in noisy places. Display wireless accessories in your clinic and give clients hands-on experiences with them. 3) Counselling and/or roleplaying may help some client develop the confidence and assertiveness needed to deal with difficult listening scenarios. Include questions about the client’s communication environments in initial intake questionnaires and during the case history to help identify candidates for wireless accessories and counselling.

Media Barriers

We live in an increasingly media-dominated world. Ability to use this technology routinely is critical to employment and social engagement. Conventional telephone use may present an insurmountable barrier to people with severe-profound hearing loss, if aided residual hearing levels remain insufficient to enable error-free telephone communication. The same can be said of intercoms and two-way radios. Even after amplification, severe to profound levels of hearing loss present a degree of residual handicap, and vision and text-based technologies may be required to help individuals achieve optimal restoration of communication function.

Strategy - assistive technologies. Wireless and hard-wired interfaces between hearing aids and a wide variety of other technologies should be the first point of reference for the clinician managing severe hearing loss. These devices help to optimize signal-to-noise ratios and the quality of audio input through hearing aids. For television viewing, it may sometimes be necessary to recommend a combination of wireless hearing-aid interfaces and open or closed captions to maximize comprehension for some clients.

The proliferation of text-based and digital communications such as email and social media present acceptable alternatives to voice based telephony. Captioned telephony (“CAP-TEL”) technology is also advancing but at the time of writing this article, still suffers from significant delay in voice to text conversion. The technology behind real-time video telephony such as Skype and some newer mobiles, is rapidly reaching a point of technical precision good enough to ensure its common usage in all telephone types including mobiles, without the annoying delays in lip and voice synchronization that make lip-reading very difficult, if not impossible. Clinicians need to keep up to date and utilize these technologies to ensure their clients’ communicative function is optimized.

Impoverished Communication Diet

Mental health for anyone, hearing-impaired or not, is significantly impacted by the frequency, quantity and quality of communication interchanges with relationship partners. Lasting and satisfying relationships cannot survive on a diet of superficial communication. Healthy relationships require meaningful and personal interaction on an ongoing basis. Indifference, inappropriate, minimal, or confusing verbal responses, negative non-verbal communication and other signs of lack of focus or interest, are communicative behaviours that create deprivation of communicative nutrition. Relationships thus affected, inevitably cool off and die.

Severe hearing loss directly affects these variables in a similar way to inequality in language proficiency. When messages are confusing or hard to understand, it is difficult to move beyond superficial communication. Even with optimal amplification there is often still a high level of residual handicap. Consequently, development of meaningful relationships, especially in noisy environments, can be very difficult. Uncertainty or confusion surrounding spoken messages and non-verbals can too easily produce inappropriate responses that only serve to slow down, or completely halt, normal relationship progression from a superficial level to a deeper, more meaningful level. Repeated communication failures will sometimes lead to compensatory communication behaviors that may be seen by people with unimpaired hearing as unusual, inappropriate or even aggressive (Weir, 2009).

Strategy - Targeted questioning. The presence of an impoverished communication diet will not always be evident without targeted questioning and careful listening to the patient. The questions in Table 1 can be used to flag a poor communication diet, especially if there is not significant changes post amplification. In this author’s experience, the majority of clients with mild to moderate hearing loss will record positive changes to all five of these targeted questions at post-fitting follow ups. For treatment strategies and rehabilitation for those clients whose communication diet is lacking, refer to Weir (2009).

Real-ear Measurements and Satisfaction

Transitioning to new hearing aids can be especially difficult for experienced users of high power instruments. Severely hearing impaired users with left corner audiograms get most of their audibility from low frequency sounds. If there is no usable hearing above 1000 Hz then typical fitting rationales that attempt to amplify above this point may have no impact except to increase the likelihood of feedback. In some cases, it may be better to turn those channels completely off. Additionally, it is not uncommon for long time hearing aid wearers of high power devices to prefer gain well above real-ear prescription target levels. Programming hearing aid gain to real-ear prescriptive targets (such as NAL-NL2 or NAL-RP) can fail to produce user satisfaction, even with adaptation counselling.

Strategy - be flexible. If a patient with severe hearing loss is reasonably happy with their existing hearing aids, but needs to upgrade to newer improved technology, perform real ear measurements with the existing hearing aids. This provides objective documentation of what the client is 'used to' listening to. If fitting the new instruments to a validated prescriptive method is your long term goal, you may need to adjust the settings in the new instruments gradually over time toward this goal, while balancing initial acceptance. Consider using multiple programs with various frequency responses and noise features (i.e. fixed directional microphones, wind noise reduction, etc.) to help find optimal settings for each client in various listening situations. Access to manual volume adjustment may also be needed for situations where background noise masks speech, as reducing the volume may help to optimize the ability to hear speech in close proximity in those settings.

For most people with severe-profound losses, the degree of residual hearing handicap even with hearing aids remains a significant barrier to communication function. Optimal use of other methodologies must be utilized in the quest to optimize social integration through restoration of communication function. Sometimes, incremental improvement from the use of newer wireless accessories will be the most that can be expected to improve towards the goal of optimizing the patients’ hearing with new hearing aid technology.

Thoughts on Cochlear Implant Candidacy

One of the main premises of this article – that the predominant focus on the restoration of hearing needs to expand to include the larger picture of restoration of communication function – applies regardless of the type of amplification. That is, it cannot be assumed that the restoration of hearing, whether via conventional hearing aids, cochlear implants, or other amplification, will automatically lead to a natural restoration of communication function. While in many cases it might, for those with life-long severe-profound hearing loss the learning curve will be steep, to say the least. The brain must not only learn to identify and process new auditory stimuli, but also learn to observe and adopt “new” expressive communication behaviours based on improved auditory input, i.e., what to say, how to say it, and when to say it. I suggest that implant candidacy assessment criteria includes objective measures of potential to learn and adopt revised expressive communication behaviours. Along these lines, I believe that implant rehabilitation programs should be expanded to include classroom and experiential exercises designed to facilitate the development of culturally appropriate listening and responding skills, particularly in relation to group participation. In my experience, a positive, ‘can-do’ personality is a good predictor of adaptability, so a measure of this factor could also be helpful in the rehabilitation process.

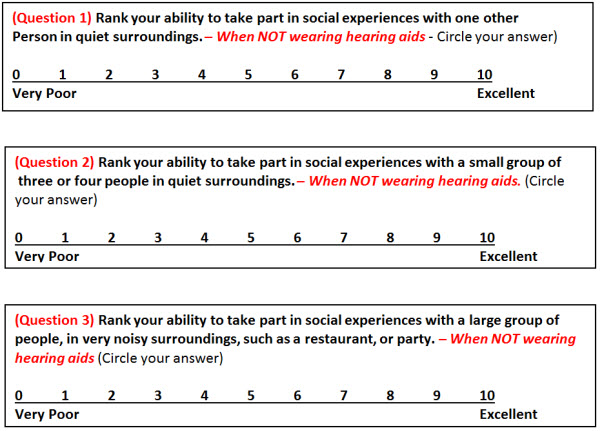

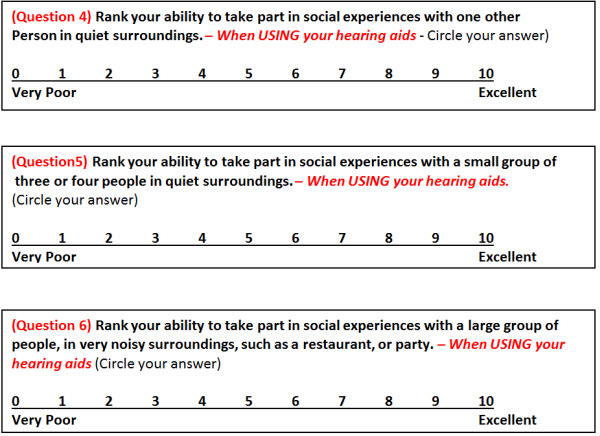

I propose that a measure of social integration performance as self-assessed by the patient be included in cochlear implant candidacy assessment protocols for adults. Social integration performance could be measured in a simple pre-fitting (Figure 2) and post-fitting scale (Figure 3), similar to that used in some of the motivational tools from Ida Institute.

Figure 2. Social Integration Scale: Pre-hearing aid fitting.

Figure 3. Social Integration Scale: Post-hearing aid fitting.

Figure 2 can be included in an initial intake and case history questionnaire. Figure 3 can be used as a post-fitting measure of social integration improvement, and can be used in conjunction with other cochlear implant assessment criteria to help plan appropriate and effective management for hearing aid users with severe-to-profound losses.

The Social Integration Scale is my own creation based on my years of dispensing experience, and my own personal experiences with profound hearing loss. It is not yet a well-researched, peer-reviewed, evidence-based tool, but I believe it is worthy of research study, and welcome contact from interested parties.

Summary

Although the number of clients with post lingual, acquired severe to profound hearing loss is small, these clients have unique and specific needs. These needs will be largely unmet if clinicians approach the aural rehabilitation process the way they do for clients who have lesser degrees of hearing loss. Implementing the strategies in this article will, at the very least, help clients with postlingual severe to profound hearing loss move closer to the goal of optimal communication function. At best, the effects can be lifechanging for these clients, impacting not only communication function, but also social and emotional well being.

The author welcomes comments and questions from readers at gmw@westnet.com.au

References

Weir, G. (2009, August). Communication diet theory: An extended foundation for hearing rehabilitation. AudiologyOnline, Article 877. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

Sockalingham, R., Lundh, P., & Schum, D. (2011, January). Severe to profound hearing loss: What do we know and how do we manage it? Hearing Review. Retrieved from www.hearingreview.com

Cite this Content as:

Weir, G. (2015, January). Severe to profound hearing loss: considerations & strategies from a clinician with hearing impairment. AudiologyOnline, Article 13124. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.