Editor's note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Selecting and Fitting Devices for Tinnitus Management, presented by Jennifer Martin, AuD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, learners will be able to:

- Define the role of sound therapy as part of the tinnitus/sound intolerance management plan.

- Explain when each type of device (hearing aid, sound generator, combination unit) would be used as part of the management plan for patients with tinnitus and sound intolerance.

- Describe the differences between fitting hearing aids for hearing loss (prosthetic) and fitting hearing aids for tinnitus and sound intolerance management (therapeutic).

Introduction

When discussing tinnitus management, it becomes evident that its nature is multifaceted. Firstly, there is the educational and counseling aspect, which offers us the opportunity to engage in meaningful conversations and provide in-depth explanations. Secondly, stress reduction and relaxation play a vital role since tinnitus patients frequently endure depression, anxiety, and other related challenges that necessitate careful attention. Lastly, the crucial aspect of therapeutic sound will be our primary focus today.

Therapeutic Sound

It's worth noting that the literature contains numerous definitions of therapeutic sound, leading to various ways of describing it. Here, I will present a few examples to demonstrate the diverse perspectives. However, despite the differences, the underlying concept remains consistent: therapeutic sound is believed to have an impact on tinnitus in some manner.

Whether it pertains to the perception of tinnitus or the individual's reaction to it, we will delve further into that aspect shortly. However, what stands out to me the most is the extensive scope of this field. In essence, our objective is to utilize sound, be it amplified through a hearing aid, transmitted through headphones, or delivered via hearing aids that offer both amplification and additional sound. Our ultimate goal is to achieve habituation, not only in regard to the perception of tinnitus but, in my view, more importantly, to the emotional response associated with tinnitus. I am hesitant to confine sound therapy to specific devices or methods. I often emphasize to my students that it encompasses a vast range of approaches, forming a broad umbrella that accommodates numerous therapeutic techniques and tools.

Today, we're discussing the use of sound, which falls under a broad category, and we'll be following similar guidelines regardless of the specific method chosen. The important thing is to stick with these guidelines, allowing flexibility in the approach. There are various methods to deliver sound. We can use speakers, headphones, pillows with speakers, and ear-level devices. Each approach has its own advantages and may be chosen based on individual preferences and needs. A lot of that choice depends on if there's hearing loss or not. To keep everything simple, today, we're going to focus on ear-level devices and how we can program those a bit differently for tinnitus and for sound intolerance.

Therapeutic Sound Guidelines

Okay, guidelines. I used to call these rules, and then I thought, eh, that's a little too strict. There aren't any hard-set rules. They're more like guidelines that help me guide my patients through the process. These guidelines are specific to my practice, and I don't believe they are universally applicable. Every professional may have their own approach. These guidelines provide a framework of thinking so that instead of everything being so nebulous, we can choose a sound that suits the patient. But what does that mean?

Well, I have three guidelines that I follow. Firstly, the sound we use shouldn't be bothersome to the patient. After all, they are already dealing with a bothersome sound – their tinnitus. So, the therapy sound should not add to their discomfort. Interestingly, I used to use the word "pleasant" to describe the sound, suggesting that it should be pleasant for the patient.

I don't use the term "pleasant" anymore because I've come to realize that many of the sounds we use are neutral, like the sound of an air conditioner. It may not be particularly lovely or joyful, but it's a neutral background sound that can still help with tinnitus. So now, I've changed that guideline to focus solely on the sound not being bothersome to the patient.

The next guideline is that the sound shouldn't interfere with communication or concentration, regardless of the situation or activity at hand. This flexibility allows us to choose different sounds for different occasions. For instance, if a patient is cooking, they may prefer to have music playing, but if they are working on a lecture, music could prove too distracting. So, the sound choice can be tailored to the specific context and need.

Another thing you'll notice is that the volume of the sound affects both of the previous aspects, which is why we emphasize using a low-level sound. Many patients may initially find a sound bothersome, such as rainfall, but by simply reducing the volume, it often becomes more tolerable. Similarly, if the sound interferes with communication, lowering the volume can resolve the issue. Setting a low-level volume is always the first step.

Moreover, a crucial aspect is that we use the sound to reduce the brain's ability to focus or zone in on the tinnitus. This approach is significant in our sound therapy process.

That doesn't necessarily imply that we need to completely mask the tinnitus or make it softer. The objective is to find a sound that distracts the patient's focus from the tinnitus. It can take various forms and doesn't always involve directly affecting the perception of the tinnitus.

So, these are the general guidelines we follow, whether we're using amplified sound or imported sounds. The approach remains consistent throughout.

Purposes

Let's discuss the purpose of these different sounds before we dive into the devices and the programming aspect. Jim Henry and his colleagues at the Portland VA have developed a program called Progressive Tinnitus Management. This program is great for clinicians just starting in tinnitus It's easy for them to understand and do, and all the information is online for free. We want to use sound to provide a sense of relief just from the stress. It's not even doing anything to the perception of the tinnitus, just listening to that sound makes the patient feel better. That's what they would call a soothing sound. If we are offering a passive diversion from the tinnitus, it's physically interfering with the ability to perceive the tinnitus, but just in a passive way. That's what they would call a background sound. Then, an active diversion where you're actively engaging the brain away from the tinnitus would be what they would call an interesting sound, okay?

Types of Sound

Within each of those categories, there are different types of sounds you can use. There are environmental sounds, whether naturally in the environment or you're playing a recorded sound of an environmental sound. There's music, of course, and there's speech. Within each of those categories, we have different options. This just gives us lots of flexibility. For example, let's say ocean, right? For a particular person, the ocean could be considered a soothing sound because they find it comfortable and relaxing, and just listening to it makes life better. I's an environmental sound, so that could be a combination for them.

For other people, let's say an interesting sound might be a podcast. That would be speech, which helps divert their attention from their tinnitus. Now, music is an interesting one because I find that it depends on if you're just a normal person like me or you're a musician. Musicians are special, and they don't view music as a soothing sound. They don't view music as a background sound. It is an interesting sound. It is active and something that they are analyzing all the time. Whereas for me, it's just sort of there in the background. You have to think about not just your own categories for these sounds but how your patient might interpret these different types of therapeutic sounds.

Ear-level devices

Then, we have lots of ways of delivering them, right? We have what I'll call sound generators, we have hearing aids, and we have combination units. I'm going to explain all of these here.

Sound generators. Sound generators are ear-level devices that often look like a hearing aid, but they have no amplification. Some have multiple sound options, and some are programmable. They come in a variety of styles, and they tend to, at least in the United States, be less expensive than hearing aids. Now, I used these a lot when I was at the clinic I worked for in Portland, Oregon, but when I moved to Singapore, the government didn't use these medically. They don't allow the import of these.

So suddenly, I had to figure out, okay, so if I have a patient who wants just to deliver sound, but they want something portable. This was before we had so many great wireless options I often would have to use hearing aids as just a sound delivery system. Sound generators are not available everywhere, but they certainly can be, so that can be one option.

Hearing aids. Hearing aids, of course, we're all familiar with, and we know that we can use them in a variety of ways. We can use just the amplifier to bring up the sounds that they need, and we also have a lot of wireless options for sound streaming and all kinds of things.

Combination units. When I was first starting, we had units called combination units. It was a combination of a hearing aid amplifier and a sound generator, and it usually looked like a BTE. You could do just the amplification or sound generator, or you could do both. In that way, it was brilliant. The difficulty was that you had to choose, am I going to fit a hearing aid only or am I going to fit a combination unit? The hearing aids didn't have streaming capabilities, so they were just hearing aids. The combination units had very outdated amplifiers, so they usually were not the best technology for hearing loss. Now, these days, we all know that most hearing aids will have built-in sounds and be able to stream in sounds for tinnitus. We don't have this conundrum anymore, necessarily of choosing one or the other. We can fit a hearing aid knowing it has all these additional capabilities. In this article, when I mention a combination unit, keep in mind I'm talking about using a hearing aid in the capacity of having access to both the amplifier and the additional sound for sound therapy.

Benefits of Amplification and Considerations

What are the benefits of amplification when we're dealing with a tinnitus patient? Obviously, if we're improving their ability to hear and just bringing in more sound, we're enriching their sound environment. We're probably going to provide background sounds they haven't been hearing very well. It could be that air conditioner, it could be music in the background, it could be voices. If those additional sounds create a comforting background if all it does is relieve some of the stress of that tinnitus signal, great. That could be one of our goals. It can actually affect the tinnitus loudness as well.

Having that background of sound could cause the tinnitus to not seem like it's poking out so much. So it's not quite so vibrant in the midst of that background sound. We also know that if we are relieving the hearing loss, we're making it easier to hear, then there's less stress. People are less tired at the end of the day. When they're less tired, they're probably going to be able to fight off their tinnitus a little bit better. So, even just giving them good amplification just for the hearing and communication aspect can be very helpful. Then, stimulating the auditory system. We all know that what we don't use, we're going to lose. We want to continue to stimulate the nervous system, continue to keep those connections active, and that's going to be good for the outcome of tinnitus in the long run.

Device Type

When we had to choose between a hearing aid and a combination unit, this was a hard decision that made me nervous. Always be open to trying both to allow patient to decide what works best for them. The worst the hearing gets in the low frequencies, you might need additional sound to create that same thing. Nowadays, we don't have to necessarily worry about that, but we always want to be thinking a few steps ahead. First of all, in our office, trying amplification only, added sound only if they don't have a hearing loss, and then the combination of both and allowing them to determine what they like, but also just keeping in mind the capabilities we want the hearing aid to be able to have down the road. What kinds of onboard sounds does it have? How good is the streaming capability with this particular hearing aid? And then we can just turn off and on those features as we need them.

Device Style

We are in a beautiful age of technology where it's making treating tinnitus easier. Typically, when we look at our device style, we are going to focus on open whenever we can. If I plug my ears, my crickets are much louder, because I'm blocking out the sound from the environment which could be reducing my tinnitus. If I'm going to use a device, my first inclination is I want to keep the ear canals open. Normally, that will be a slim tube BTE, a receiver in the canal, or something like that.

The nice thing is we have domes to determine what's the best combination for that patient. Open, but closed enough to prevent feedback and things like that. If we just can't, if the hearing loss is just too great or we're getting feedback issues, and of course, we're just going to try to do the most open fit that we can, even if we can't call it open. We'll talk in a bit about how that's where feedback control systems come in handy when we're trying to do this.

Monaural vs. Binaural

If I have hearing loss in both ears, but tinnitus in one ear, do I fit for both or do I fit for one? I would say that most people agree these days that fit for hearing loss first. Don't worry about if the tinnitus is only on one side because honestly, the way that our ears and our brain are built, we've got neural connections going straight up, we've got neural connections crossing, we've got a lot of different pathways going on. The more input we can give, the better. If we're creating auditory balance, if we have a more normal function, then we expect to avoid some of the pitfalls that we can sometimes create if we're just amplifying one side. So fit for the hearing loss and then we're going to adjust for the tinnitus if it's only in one ear.

Prosthetic vs. Therapeutic Fitting

Grant Searchfield in New Zealand talked about the prosthetic fitting of hearing aids versus the therapeutic fitting of hearing aids. When we first become audiologists and we're fitting for hearing loss, we're fitting prosthetically. Just like if we were missing a leg, we put on a prosthetic leg, right? So, we're fitting the hearing aid to replace the lost hearing, and that is how we're trained. That is where all of the research and development of hearing aids goes into. They're going to focus on audibility and speech clarity. However, tinnitus often requires us to fit therapeutically where our goals are different. I want the hearing aid to be providing some level of noise for the tinnitus part. That's what we're going to focus on today is the changes that we are making to the programming to allow us to hopefully have a more positive effect on the tinnitus perception. The nice thing is that you can flow fluidly back and forth between prosthetic and therapeutic. If your patient is having more problem with tinnitus, now you can do therapeutic, but as it becomes more of a hearing problem, you can go towards prosthetic. So it's not really a choice between one or the other.

Method 1. How do we choose which one we're going to use? In general, this is what I've seen. Method 1 would be determining what's the bigger problem. Is this person more bothered by the tinnitus? Are they more bothered by the hearing loss? And then fitting accordingly based on that. If it's the hearing loss, you're going to fit for the hearing loss and the patient's communication needs. Any benefit we get to the tinnitus from doing that, fantastic. That's great, right? But it's the secondary goal. If they tell you that tinnitus is their bigger problem, then we're going to fit more therapeutically. We're going to go primarily for tinnitus relief. Any improved communication they have is now the secondary goal. We can move back and forth between those. There are a lot of ways of determining this. Again, the Progressive Tinnitus Management program has a lovely worksheet called the Tinnitus and Hearing Survey. It has four questions about hearing, four about tinnitus, and one about sound intolerance. You can see based on the score, which is the bigger concern for the patient. The other cool thing is, is that we can have one program that's more suitable for the hearing loss. It can be more prosthetic. You can have another program that is more suitable for the tinnitus. It's more therapeutic. So, you don't have to pigeonhole yourself into one program either. You can be pretty flexible.

Method 2. The second method is what the Progressive Tinnitus Management program talks about, which is just always focusing on hearing loss first. Progressive Tinnitus Management, it's a progressive program. The majority of patients will get some relief from tinnitus with a well-fit hearing aid. If the patient does not experience enough benefit for the tinnitus over time, changes can be made to the programming specific to tinnitus

Acoustic Programming

Here are some considerations for acoustic programming:

- Use feedback reduction for most open fit

- Disable internal noise reduction (expansion)

- Disable environmental noise reduction (ANR)

- Low compression knee point

- Omnidirectional microphone setting

- Fitting protocol: DSL I/O v5

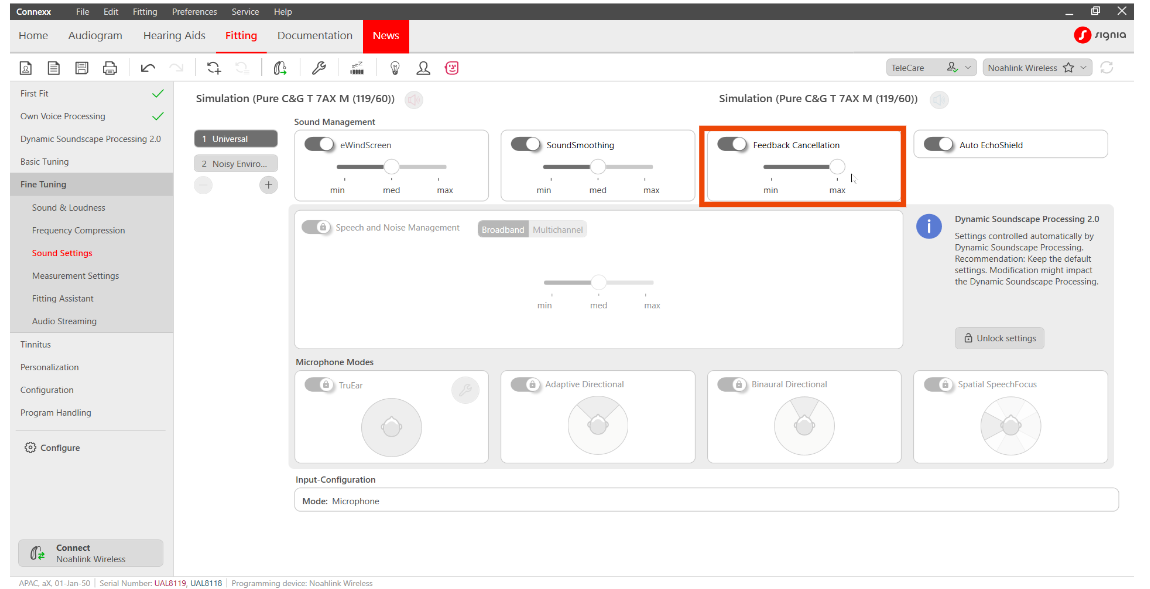

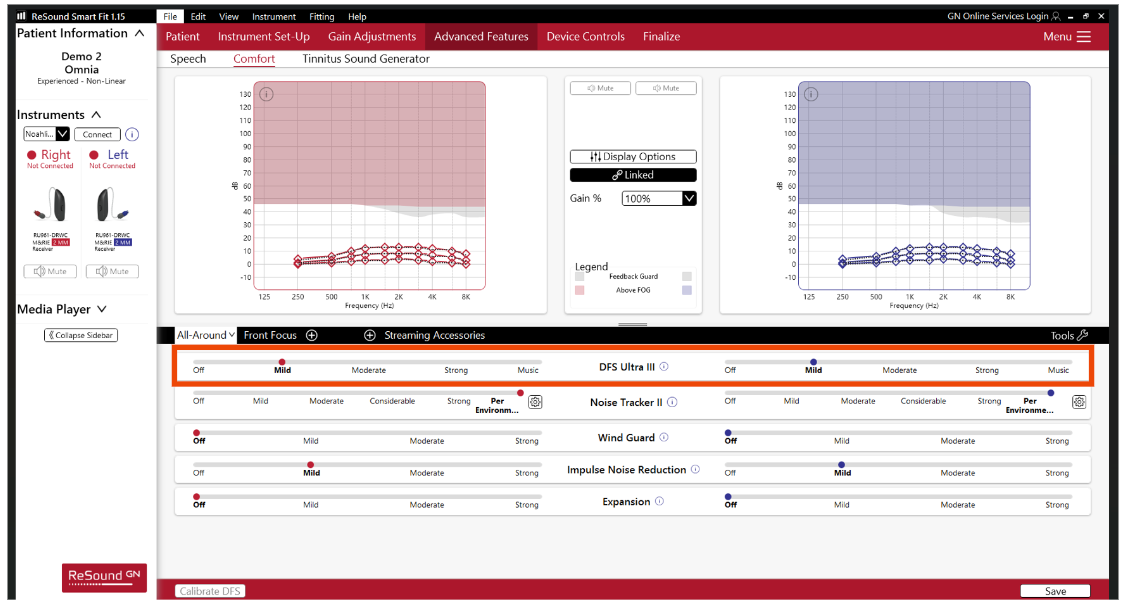

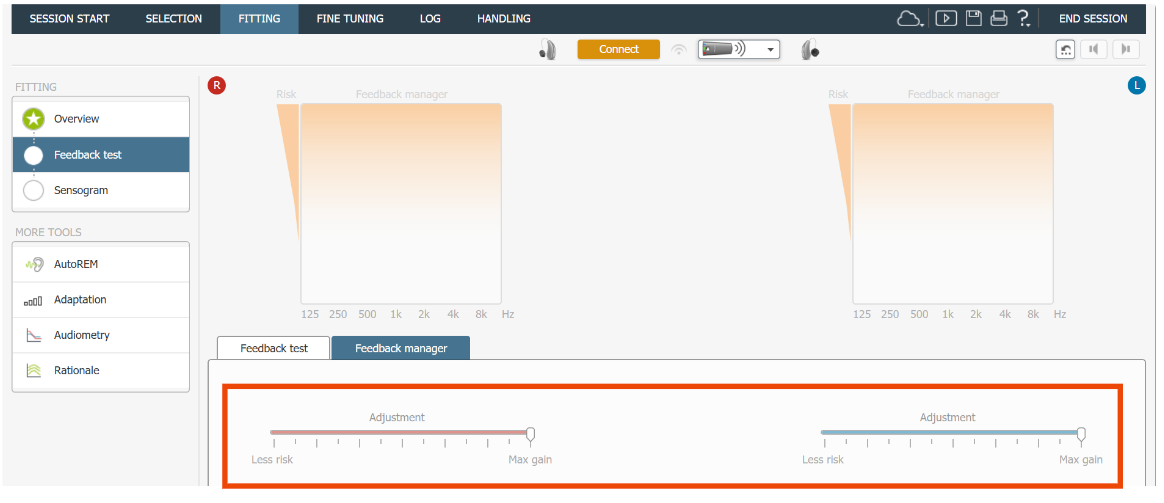

Feedback Reduction

Let's start with feedback reduction. We talked about how with tinnitus, we will almost always try to go as open as possible. This is a tough one for some of my students or new trainees to understand because they're so used to looking at low-frequency hearing. I rely on my feedback system more as I'm trying to keep that ear canal open. Think about the different products that you fit; which are the ones that have the feedback reduction systems that you really like and that you've learned to depend on? Do they have multiple styles of feedback reduction within the same device? You can see that some of Signia's features in certain hearing aids will be an on/off situation. Some are going to have gradations. I'm never implying that when I say, you may need to use more feedback control; you don't have to automatically go in and just crank it all the way up to maximum. If you're not getting feedback, fantastic, that's great. Don't worry about it. But if you are getting feedback, maybe you turn it on a little bit, maybe you activate it fully.

Figure 1. Signia feedback cancellation screen.

Figure 2. ReSound feedback cancellation screen.

![]()

Figure 3. Oticon feedback cancellation screen.

Figure 4. Widex feedback cancellation screen.

Expansion

Expansion was developed to allow hearing aids to have lower compression thresholds or compression knee points but not be so noisy internally. Also, for very soft gain in the environment to not be bothersome. Before we had these great circuits, I remember patients would say, when I'm sitting in my office, and nobody is speaking to me, I hear like low-level sounds. I hear my computer hum like it's super loud, and things like that. They were just getting too much super soft gain, or they could hear the circuit actually working and the noise. Expansion is fantastic when we're trying to make the hearing aid quieter for communication. If we want to create some background sound so that the patient has a built-in sound generator, we might want to turn that down or turn it off

Disable Environmental Noise Reduction

Instead of fine-tuning the internal noise reduction you will want to disable external noise reduction or automatic noise reduction. Sometimes it's speech enhancement, which is noise reduction to enhance speech. We are familiar with these circuits because we are trying to adjust these so that our patients can understand speech and noise better, but we might not want so much noise processing if our goal is more of a therapeutic fitting.

Low Compression Knee Point

This is a tricky one. As much as my students hate learning about compression, we all know it's really important. It can be a tricky thing for new students to understand, but we know that a lower compression knee point is going to give us more soft input gain. Which can be a double-edged sword. To a certain extent, that can help with speech, but at some point for communication purposes, it might bring in too much low-level noise. With tinnitus, because we want to have a noise floor, a lower compression knee point can be helpful. However, not everyone lets you change that. It depends on the manufacturer. This is something that I still talk to people about, but just know that your product may not give you the option of doing this. You may only be able to adjust your compression ratio, not your compression knee point.

Omnidirectional Microphone Setting

Omnidirectional versus directional. We are so used to fitting directionally because, again, we're trying to control noise. We're trying to keep sound that's not important behind us or to the sides from interfering with what we're hearing in the front. In tinnitus, we may not want that, we may want more of a noise floor. Sometimes, you might want to think about if you're in an automatically changing directional mode. Do you want that, or do you want to just freeze it in omnidirectional? Also, some of the directional can get very, very directional. We cutting out too much other sound? That's just something that you can play with a little bit. Again, have different programs. If you feel like for communication, it's better this way, but for tinnitus, it's better this way, you can set different programs for that.

Fitting protocol: DSL I/O v5

The last thing we'll talk about is the fitting protocol. There was a really interesting article that Grant Searchfield did, that looked at what was preferred by patients. They fit a bunch of people, and they looked at preferences. What was interesting was most people, the majority of people, preferred an NAL target for communication. If they wanted to focus on speech and speech understanding, they liked the NAL. If they were focusing on tinnitus relief, they preferred the DSL. And those of you who are familiar with these prescription formulas, you can understand why with the differences in gain and things like that.

One thing we can think about, again, if we go back to, what is the primary concern? If the primary concern is hearing loss, then maybe we start with an NAL target and see how that goes. If the primary concern is the tinnitus, maybe we start with a DSL and see how that goes. The beautiful thing is that this is so changeable in the moment. I used to feel like once I committed to a target, I had to stick with it forever whether the patient liked it or not, it's like a marriage or something. Then I realized, hey, it's a click of a button. Now, the only thing we have to keep in mind is that of course, if we're changing our whole fitting strategy, we're going to have to repeat our probe microphone measurements.

I am a big proponent of verifying fittings for tinnitus, just like you would for anything else, because we don't know what's getting into the actual hearing mechanism. We're just kind of making guesses from our computer screens until we verify that with something. Keep in mind, of course, that if you switch that, you will have to rerun your probe microphone. Most companies now offer a whole lot of options for you to choose from. You can pick all kinds of different things.

Most people who see you about this are already very much on edge. There are certain tests they don't want you to do because it's very frightening for them. A lot of times, we may have to deal with this first before we can even get to the tinnitus, but that's kind of our first choice. So our first choice is, are we going to do just a sound generator so that we're going to get them used to more and more sound input over time so that we can increase that dynamic range, basically like physiotherapy for the brain, right? Or do we need to think about hearing aid or hearing aid with additional sound? Okay, so a combination unit.

Considerations: Sound Intolerance

Sound Generator versus Hearing Aid/Combination Unit

First thing is, do they have hearing loss? You may be fine with just a sound generator if they do not. Does the introduction of low-level background sound make it difficult to hear quiet conversation Can the hearing loss be addressed at the same time or does the SI have to be dealt with first? Of course, you can also use headphones and things like that, but we're focusing on ear-level devices today, so sound generators. However, if you begin fitting them and then maybe they're borderline normal, maybe they're at 20-25 dB thresholds, and you put in that sound, and it's great, except that now they're having trouble hearing soft voices. Maybe they do need a little amplification just to overcome the additional kind of hearing loss that's being caused by the sound that you're putting in. Then, can you deal with both at the same time by doing that or do you really have to desensitize the system first and expand that dynamic range before you can even deal with therapeutic sound for the tinnitus?

Occlusion versus Venting

Some things to think about when you're trying to choose devices. We also need to think about this whole occlusion versus venting issue again because it's going to be the exact opposite of tinnitus. Tinnitus, everything is open. I would argue that for sound intolerance, you're usually going to start with complete occlusion, and then you're going to work away from occlusion over time. If we fully occlude the fitting, we achieve a few things. First of all, you do get some passive reduction of those sounds that have been offending the person. Keep in mind that most people with sound intolerance have also developed a level of phonophobia. So if they've been driven crazy by certain sounds for a long enough period of time, they become fearful of those sounds. Starting with a fully occluded fitting allows for maximum passive filtering of unwanted external sound and maximum control over what sound is entering the ear. Amplification and limiting will only be applied if the sound is forced through the microphone and amplifier. A greater sense of control for the patient over what is allowed to enter their ears. Fitting can be made more open as sound intolerance improves. We are going to use the hearing aid circuit or the sound generator to stimulate at the same time that we're plugging, so that's very, very important. If we have an occluded fit, we're going to have control over how that sound is being managed by the amplifier. So we all know that if we can do all the crazy stuff inside the hearing aid we want, but if we fit with an open fit, half of those things aren't even working because a bunch of the sound is getting through to the eardrum through the open ear canal. It's not even going through the circuit. By occluding, we're forcing the sound to go through the microphone, go through the amplifier, and then to the eardrum. If you have set some of these settings we're going to talk about in a moment if you have done all your due diligence on doing that, you're much more guaranteed those things are going to be working if you're using an occluded fit. By doing both of those things, you can encourage the patient that they have control. Yes, we're going to be putting sound into your ears, but you have control. We're blocking out the offensive sounds, and we're heavily controlling the sounds that are getting into your ears. You don't need to worry, we're going to manage that for you.

Programming Modifications

- Low compression knee point + higher than normal compression ratio

- Use hearing aid as amplifier and limiter

- As sound intolerance improves, compression ratios can gradually be reduced

- Reduce maximum power output (MPO)

- Before adjusting the MPO in the HA, you may need to change the LDL value from HL to SPL

Special Considerations

- Each tinnitus patient is unique and requires individualized care

- Program devices to meet the patient’s individual hearing, tinnitus and comfort needs

- Perform probe microphone measurements whenever possible to verify acoustic fit

- Multi-disciplinary care is best

- If you are not a tinnitus specialist, understand when it may be necessary to refer

Each tinnitus patient is unique, and they just require us to be very flexible. I consider those of us who do tinnitus; we're kind of out-of-the-box thinkers. Whenever people look at my fittings, they probably wonder what she is doing with them. We have to make sure that the devices we're fitting are meeting the individual needs for hearing, tinnitus, comfort and the sound intolerance. Probe microphone measurements are important whenever possible. Now obviously, double-checking your MPOs could be a little hard on a sound intolerance patient that may have to come later. As we're adjusting the MPOs inside, we are guessing at that sometimes, but at least measuring your soft gain; hopefully, you can get your moderate gain.

Multidisciplinary care is always best. We can work on all of this with our patients while they're also seeing a psychologist, a psychiatrist, an ENT doctor, or whoever they need to see to be managing some of the other issues as well. I would love more people who focus on hearing aids to know how to fit hearing aids for tinnitus and sound intolerance.

References

Folmer RL, Carroll, JR. (2006) Long-Term Effectiveness of Ear-Level Devices for Tinnitus. Oto Head Neck Surg 134: 132-137.

Henry JA, Zaugg TL, Myers PJ, Kendall CJ. (2010) Progressive Tinnitus Management: Clinical Handbook for Audiologists.

Henry JA, Zaugg TL, Myers PJ, Schechter MA. (2008) Using Therapeutic Sound With Progressive Audiologic Tinnitus Management. Trends in Amplification 12: 188-209.

Hoare DJ, Searchfield GD, Refaie AE, Henry JA. (2014) Sound Therapy for Tinnitus Management: Practicable Options. J Am Acad Audiol 25: 62-75.

McNeil C, Tavora-Vieira D, Alnafjan F, Searchfield GD, Welch D. (2012) Tinnitus pitch, masking, and the effectiveness of hearing aids for tinnitus therapy. Intl j Aud 12: 914-919.

Searchfield GD. (2006) Hearing Aids and Tinnitus. In Tyler RS (Editor), Tinnitus Treatment

Searchfield GD, Kaur M, Martin WH. (2010) Hearing aids as an adjunct to counseling: Tinnitus patients who choose amplification do better than those that don’t. Intl J Aud

Shekhawat GS, Searchfield, GD, Kobayashi K, Stinear CM. (2013) Prescription of hearing-aid ouput for tinnitus relief. Intl J Aud 9: 617-625.

Citation

Martin, J. (2023). Selecting and fitting devices for tinnitus management. AudiologyOnline, Article 28609. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com