Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Describe evolution of the audiological test battery.

- Define what is meant by "standard of care", "evidence-based practice" and "value added test".

- List advantages of specific test procedures in assessing auditory functions.

Historical Perspective on Diagnostic Audiology

We can learn a lot by looking at the history of our current diagnostic test battery. The earliest research that led to our current test battery goes back to the 1700s and 1800s. It started with discoveries and descriptions of the anatomy of the auditory system, and also with people like the German physicist Helmholtz, who was among the first people to study sound.

We'll start our discussion of the scientific foundations of audiology toward the end of the first half of the last century, in the 1940s and 1950s. Most of the people conducting this research at that time were born in the late 1800s to early 1900s. There's an interesting parallel here. The grandfathers of audiology (they were mostly men at that time) were born at the same time that my biological grandfathers were born; one was born 1895, and the other was born 1899. So, many of us audiologists were growing up at the same time that the profession of audiology was 'growing up', if you will.

A well-known psycho-acoustician in that era was S.S. Stevens. He developed a lab at Harvard University called the Psychoacoustics Laboratory. It was the leading research laboratory for hearing during the 1940s and 1950s. Many of the people who worked in that lab, starting out perhaps as graduate assistants or junior researchers, went on to become leaders in the field of hearing science. One of those people was Georg von Bekesy, who was from Hungary. He's truly one of the our audiology grandparents. He was not an audiologist; he was a hearing scientist, and he mainly focused on cochlear function, cochlear anatomy, and cochlear mechanics. One of his most notable accomplishments was being awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1961. For a short time in his career he worked at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, where the Nobel Prize is awarded. von Bekesy made many contributions, but most audiologists know his name because of an audiometer that he had specifically built for his purposes, now known as the Bekesy audiometer. von Bekesy laid the groundwork for much of what we now are including in our diagnostic test battery.

Another big name from that era was Harvey Fletcher; he was also born in the late 1800s. He made many contributions to our field through his work on speech perception. Much of his research was done when he was employed at the Bell Telephone Laboratories in New Jersey. We would not have many of the speech materials that we have today if it weren't for Harvey Fletcher.

Another person of that era who made a significant contribution to our field is Hallowell Davis. We think of his work mainly in terms of auditory evoked responses, but he was a first-class hearing scientist in general. In addition to discovering the auditory late response, and conducting research on all of the auditory evoked responses, he wrote some text books that influenced generations of audiologists. In the 1950s, he authored one of the very first textbooks focusing exclusively on hearing. His book Hearing and Deafness, written with a colleague, Richard Silverman, was used by my generation of audiology students. In the early 1970s, that was virtually the text book to use for learning about hearing in introduction audiology courses, and I still have that text book. Hallowell Davis was certainly one of our audiology grandparents, who helped to develop the procedures that we now use.

Ira Hirsch was at the psycho-acoustical laboratory and a close colleague of Hallowell Davis. He was born a little bit later and died not that long ago. He wrote one of the very first books on how to measure hearing, and so a lot of the procedures that we now use were first described in his text book. We could call him one of our audiology grandparents as well.

Another person born in the early 1900s who had a great influence on audiology and the procedures we use is Robert Galambos. He also died relatively recently. Many audiologists my age knew him, and he knew many of the older audiologists that we were learning from as we were students.

World War II and Audiology

As you probably know, audiology itself started in World War II. During World War II, there were hundreds of thousands of men and women who had noise-induced hearing loss. Physicians, surgeons, otolaryngologists were telling them, "There's nothing we can do for you. We can't operate, we can't give you medicine. You're just going to have to somehow deal with your hearing loss." This was a major problem. In the United States, the military recognized this, so they assigned several people to try to rehabilitate these soldiers and sailors, marines, and airmen, to help them communicate more effectively. After the war, these individuals had to go back to jobs, and resume their normal lives. There really was no profession to turn to, at that point, to manage the hearing loss. The people who were conducting the initial hearing tests ere not audiologists as there was no profession of audiology during that era. They were mostly people who had something to do with hearing or speech, and they'd been assigned this task of providing services to this huge group of people.

Raymond Carhart was the person who had been selected by the military to really lead this group. He was a captain in the United States Army, and he developed the very first test battery for evaluating hearing. That test battery was reported first in 1946, more than 70 years ago. If you look at the tests in that test battery, they are quite familiar. In fact, I dare say that many audiologists are using only those tests, and none others, as their routine test battery, even today.

To a large extent, we need to rethink our diagnostic test battery, because it's at least 70 years old. Now, I'm not saying that because some technique or procedure is old that it's no longer relevant. I'm a strong proponent of using procedures that are time-tested and proven to be valuable over many years. However, over the past 70 years, a lot of research has produced new procedures that have some advantages in evaluating hearing over some of the older procedures. We're not necessarily going to eliminate the old procedures, but we need to know when to use the newer ones.

After World War II, Raymond Carhart was discharged from the army, and founded the very first program in audiology at Northwestern University. Many of the well-respected leaders in audiology in the early 1950s were Raymond Carhart's students, including James Jerger. James Jerger was a young student at Northwestern University in the late '40s and early '50s, and he picked up where Raymond Carhart left off. He is often referred to as the father of diagnostic audiology. You can read about his career and contributions in his book, A Life in Audiology. I was a student of James Jerger. I'm very interested in seeing us continue to advance the diagnostic audiology test battery, just as my mentor did, and just has Raymond Carhart did before him.

When your test battery is outdated, it may not be as effective or efficient as it could be, and then your diagnosis may not be as accurate. Ultimately, the patient outcome may be poor. So, the stakes are very high for using an updated, modern test battery.

Standard of Care in Audiology: Best Practice is Research-Based Practice

It is important to understand how we can be sure that we are providing the highest standard of care, or at least an adequate standard of care. The concept behind standard of care, as well as underlying the discussion of the test battery, is that we must use research-based procedures. We must do in audiology what has been proven to work. That concept is very nicely summarized in this quote by Leonardo da Vinci. "Those who fall in love with practice without science are like a sailor who steers a ship without a rudder or a compass and who never knows where they'll end up." With research supported procedures and treatment options, we know we're going to achieve the goals that we set out to achieve because research has proven it. If we don't base our procedures on research, we don't know whether the patient will be helped or not or whether the diagnosis will be accurate or not. Standard of care that is based on research and evidence-based practice is based on different types of evidence.

Levels of Evidence

There are levels of evidence that are related to their quality. The first level of evidence, well-designed meta-analysis of randomized control trials, is by far the strongest. If you can say, "I am using this procedure" or "I'm treating the patient in this way because many studies have been published in the peer-reviewed literature that support this technique or this approach," then you're 100% certain it will be effective. It means you're taking the very best studies and then you're looking at the collected group data for all of those studies, so there's almost no chance that you could be wrong in your conclusions.

The lowest level of evidence would be number four - recommendations of committees that consist of experts such as consensus conferences. , where everybody agrees "Well, this technique should be used," or "This technique is effective," or "This treatment option works," or clinical experience, and you can see that there are other categories of evidence from the number four all the way up to 1a.

When you now are providing quality care in audiology it should be evidence-based and the type of evidence that is used to support what you're doing is also very important.

What is the best way to assure that you are providing standard of care? As clinical audiologists, most of us believe we are providing standard of care, and that we're not providing substandard care. Audiology care may mean hearing screening, diagnosing hearing loss, treating a patient's problem such as tinnitus, fitting hearing aids or cochlear implants, or providing vestibular services. The best way to prove that you are providing standard of care is by following clinical practice guidelines. Clinical practice guidelines have been agreed upon the profession and they're all evidence-based or research-based. Clinical practice guidelines are consistent with local, regional, national clinical practice. Very often these guidelines are actually developed by multidisciplinary groups, such as the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. They're almost always approved and endorsed by national professional organizations, like the American Academy of Audiology. They're also consistent with statements of scope of practice. In other words, we're practicing audiology within our scope; we're doing things that we're trained and have experience in doing, and of course we are following ethical practices. One way to define a standard of care, and this is a very typical legal definition, is: The degree of caution that a reasonable person should exercise in a given situation so as to avoid causing injury.

In audiology and other health professions, we want to do no harm. We have two goals: to try and help improve the patient's quality of life by helping them use their hearing more effectively, but at the same time, we want to do no harm in our attempts to help them. There are many examples of patients who are worse off after they go to see a health professional, and more than a quarter of a million people in the United States alone die every year due to medical errors. Standard of care is a very important concept and in rethinking our diagnostic test battery, our ultimate goal is to enhance the standard of care that we provide our patients.

Value Added Tests (VATs)

A value added test (VAT) adds value to the diagnosis of a patient. Let's get into the details of what this means. Why would we want to include these VATs in the test battery? As an example, consider a patient who calls your receptionist and reports trouble hearing. Your receptionist schedules an appointment for an audiological evaluation. How are you going to perform that evaluation? Many of you will probably perform the same test battery with every patient. You may use procedures that you've used in the past that you learned about in your graduate program, for which you have equipment in your clinic. Those are not good reasons to use those procedures.

What you really need to be thinking is "What information do I need to acquire to manage this patient?" The answer to that question will be based on their history and perhaps on other evaluations they've had in the past. The tests you conduct may be based on the patient's age, cognitive status, or other factors, but you want to use procedures that are going to contribute to the diagnosis. Whenever you select a procedure to perform in your assessment of a patient, ultimately, the information from that procedure, will lead to a better outcome for the patient.

For example, let's say the patient is 55-years-old, cognitively intact, and is college-educated and employed. The audiogram and OAEs are normal, and you have no other evidence suggesting that they have a peripheral hearing loss. You're about to perform the speech reception threshold test by administering Spondee words and gradually reducing the intensity. Ask yourself what information that test will contribute to the management of the patient, what you will differently based on the test results, and how the results will impact a better outcome for that patient. I would suggest you'd have a hard time defending the time spent on that procedure.

A VAT provides information that you're not getting from other procedures or enables you to acquire information more quickly and efficiently than other procedures. If two procedures give you the same information but one takes five minutes and one takes 30 seconds, you use the quicker test. Another factor is risk. You may have two procedures that both give you the same information, but one is high risk and one is less risk - you should use the procedure that has less risk.

You may be wondering what procedures in audiology pose risk. Here is an example: A six-month-old baby comes in for an evaluation due to concern about hearing. There's hearing loss in the family and the child failed a hearing screening. You have the option of performing some very low risk procedures like OAEs, acoustic reflex measurements with a broadband noise stimulus, and sound field audiometry. You also could perform an ABR, but this child is very active and you would need to perform a sedated ABR under anesthesia. The VAT would be the test that posed less risk, even though the information you get from the tests may be essentially the same.

Another value-added factor is cost. If you've got two procedures, and all else being equal, one is expensive while the other is inexpensive, go with the inexpensive procedure. VATs are those that are more reliable, such as objective tests. Objective tests like OAEs, acoustic reflexes, tympanometry, and ABR, are more reliable and valid in very young children or with patients where cognition is an issue as compared to behavioral tests.

Some tests are very sensitive to specific types of auditory dysfunction. So if we're rethinking our test battery, the ideal test battery will include tests that are very sensitive to the problem that we think the patient might have. If we think the person might have a middle ear disorder and a conductive hearing loss, we want tests that are very sensitive to middle ear dysfunction. If we think the person's problem may be a central auditory problem, we don't want to be only using tests like tympanometry, for example, that evaluate just the ear itself. In this case, we need to focus on tests that evaluate auditory processing.

Sensitivity is important but so is specificity. In any diagnostic assessment, it's ideal if we can use procedures that tell us exactly where in the auditory system the dysfunction is located as that information is almost always necessary to manage the patient.

VATs give us a more accurate diagnosis more quickly with less risk, and that information is very useful in managing a patient. That information will contribute to a better outcome for the patient and that's our ultimate goal.

Old vs. New Procedures

As I mentioned earlier, the point of rethinking your test battery is not to simply get rid of old procedures because they're old. The point is to select procedures that are likely to add value to the diagnosis, to patient management, and that will ultimately improve the patient's outcome. In some cases, old procedures that have been around for a long time may actually add value, while in other cases, older procedures may not be useful with a particular patient. Rather than say you should never perform a particular procedure, my point is that you need to take a critical look at each procedure for each given patient. You should not automatically perform a procedure on every patient as part of a protocol whether they need it or not.

What's the downside? Spending time on a procedure that doesn't add value means you might not get the information you need to manage the patient, and if you'd made a different choice, you might have the results needed to manage the patient. Some old procedures almost always add value. It's rare to find a patient where tympanometry doesn't help you rule out a middle ear abnormality or confirm it. Acoustic reflexes are extremely valuable and most audiologists don't use them. OAEs are certainly more recent than some of the other procedures in the original test battery, and they almost always add value. Some traditional test procedures like speech reception threshold, bone conduction, word recognition testing in quiet at 40 dB SL very often don't give you the information you need. There's nothing wrong with performing them, but they take time, cost money, and don't always give you the information that answers your questions about the patient. Sometimes they are not value-added tests.

Examples - A Critical Look at Three Traditional Procedures

SRT. The speech reception threshold (SRT) is an old, trusted procedures that has been around since the late 1940s. In my clinical experience of more than 40 years, I have found that sometimes this test is useless. When I was supervising students, it was difficult to watch a student perform this test, and utilize valuable time with the patient only to find that the results were normal, when I knew from the other test results that the SRT would be normal. One of my students, Emily Roscher, and I did a study that looked at the clinical utility of the SRT. We reviewed 1,000 audiograms and concluded that the SRT in the majority of patients did not contribute to the diagnosis of hearing loss. I know that sounds like heresy, but that was what we found. In young children, speech reception threshold testing is always a good idea. In older adults, particularly when there's some concern about cognitive function and the reliability of the patient's responses is questionable, then speech reception threshold testing is helpful. When you are concerned about the validity of the test results, for example, when you have a patient with a false or exaggerated hearing loss, speech reception threshold testing is valuable. It has no value in persons with normal hearing thresholds and good reliability. In patients with sloping hearing loss who have normal or near normal low frequency hearing, it also has little utility as there will be a greater PTA-SRT discrepancy.

Margolis and Saly (2008) looked at the distribution of hearing loss characteristics in a clinical population. They looked at records for more than 16,000 patients from an academic health center audiology clinic, and found that in more than 53% of the patients with hearing loss, the age was between 20 and 70 years. So if you're in a typical clinic, for over half the patients, the speech reception threshold may very well not be needed. There is usually no question about the validity of the test results and the pure tone average and speech pure tone thresholds will likely give you all the information you need about threshold in those patients.

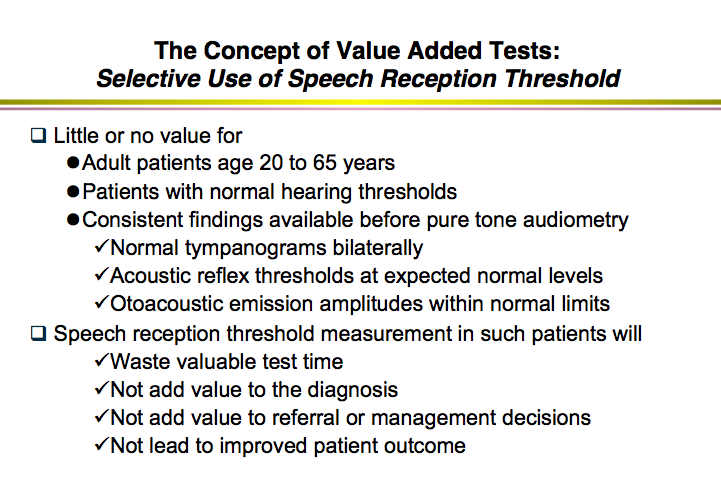

Use the SRT selectively if you want to rethink your diagnostic test battery and include more value-added tests. Don't use it on every patient; use it on the patients where it's likely to provide some value. We've kind of already gone over this information. If the speech reception threshold information is not going to add to the diagnosis or help you manage the patient more effectively, then you're just wasting time and it's not really important to the test battery, so don't do it. A summary of factors to consider when determining whether to conduct SRT testing is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Value added tests: Selective use of SRT testing.

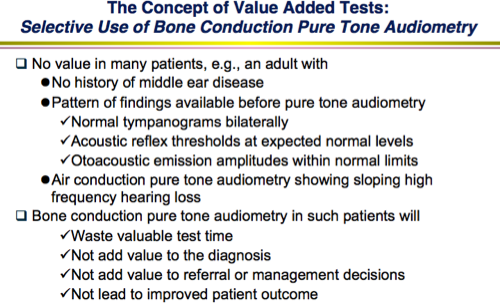

Bone conduction audiometry. The same is true for bone conduction audiometry. Most audiologists always perform air conduction testing, bone conduction testing, and speech audiometry. That same study by Margolis and Saly (2008) looked at records for 27,554 ears and found that in 15% were normal and 45% had a sensorineural loss; this means for the majority of patients there's no conductive component. If there is no history of conductive hearing loss, no abnormality on otoscopic inspection, normal tympanograms, normal OAEs in the low frequencies, and present acoustic reflexes, then there is no possible middle ear problem. Why waste test time on bone conduction testing?

Ask yourself, "When should I do bone conduction testing - when will it add value?" If you find that the patient has no risk factors for middle ear problems and no indication on other key diagnostic procedures (tympanometry, acoustic reflex testing, OAEs, etc.) that there is a middle ear issue, then bone conduction testing won't add value to the diagnosis or management, and won't lead to improved outcome. A summary of factors to consider when determining whether bone conduction pure tone audiometry is a VAT is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Value added tests: Selective use of bone conduction pure tone audiometry.

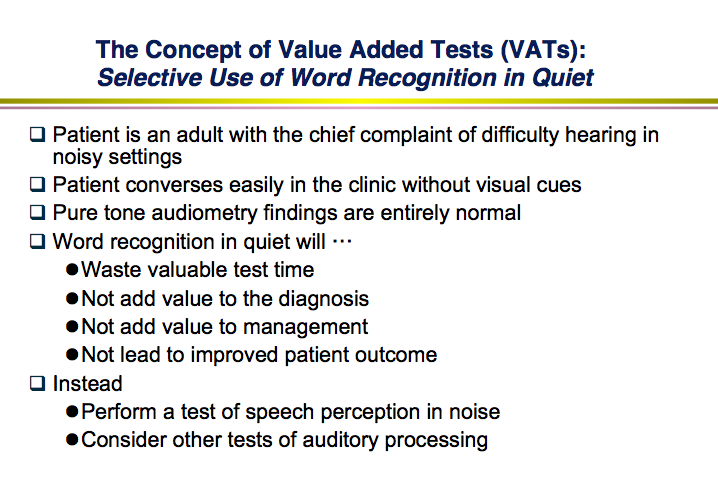

Word recognition testing in quiet. Sometimes work recognition testing is inaccurately referred to as speech discrimination, but it's really not a discrimination task. Word recognition testing is simply recognizing words and it is typically done in quiet. Many patients come into the clinic and report that they have no difficulty hearing in quiet, but they have problem hearing in noisy places such as restaurants. Word recognition testing in quiet will waste valuable test time in that case - it won't contribute to the diagnosis or management, and will not improve the outcome. If you rethink your diagnostic test battery and do not include tests that do not add value, you will have more time to focus on tests on will help you evaluate the patient. In the case of patients who report difficulty hearing in noise, value added tests might include word recognition in noise testing or tests of auditory processing. A summary of factors to consider for selective use of word recognition testing in quiet is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Value added tests: Selective use of word recognition testing in quiet.

Guidelines for Efficient and Effective Diagnostic Test Batteries

Let's review some guidelines for putting together a test battery that is effective and efficient.

One of the reasons for selecting value added tests is time. I mentioned earlier that if you have two clinical procedures that are equivalent, but one takes 1 minute and one takes 5 minutes, you should use the quicker test. The efficient use of time in a clinic means that you can see more patients and be more productive. Being more efficient may also mean having time to perform additional procedures that will add value, or having more time to counsel the patient. So, saving time often means you can do a better job diagnosing hearing loss. You can perform the tests that answer the questions that are most important for the diagnosis and management of the patient.

This is all tied in to clinical guidelines. In the 1990s, efforts were made throughout healthcare to bring consistency to clinical care in order to improve quality. Just after 2000, the American Academy of Audiology began developing clinical practice guidelines. Today there are many clinical guidelines in audiology - for example, the 2007 Joint Committee on Infant Healthcare (JCIH) Position Statement, the 2009 Clinical Guidelines for Ototoxicity Assessment and Monitoring, and many others. The American Speech Language and Hearing Association has developed guidelines. There are many international guidelines as well; the guidelines for audiology in the US are not the only clinical practice guidelines. In fact, the US does not have guidelines for tympanometry but the procedure is the same everywhere. People use similar equipment, and the goals are the same for using tympanometry in the diagnosis of hearing loss, so why not rely on guidelines from other countries? There is no reason not to do so. Wherever you're located, you can utilize clinical practice guidelines from around the world. There are several guidelines listed in your handout. Effective and efficient test batteries are consistent with clinical practice guidelines. Rethinking your test battery must be done in the context of using evidenced-based procedures that are supported by clinical practice guidelines and follow standard of care.

Modern Diagnostic Audiologic Test Battery - Example

Let's look at an example of an effective and efficient, modern test battery that uses value-added tests, follows standard of care, and uses procedures that are included in accepted clinical practice guidelines. Remember that our goal is to get the most information in the least time. For reasonably cooperative school-age children through adults, you should be able to get all the information needed about the peripheral auditory system and screen their central auditory system in 30 to 45 minutes. The test battery would include otoscopy, followed by objective tests: OAEs and aural immittance measures, including acoustic reflexes in most cases. Behavioral measures also play a role, but they are not the only measures included. The behavioral measures would include pure tone audiometry, using an automated technique when appropriate. Today there are automated audiometers that can test some patients without an audiologist being involved at all; a technician or assistant can give the patient the directions and put the earphones on. This test battery includes bone conduction measurement only as indicated. High frequency audiometry (> 8000 Hz) would be included as indicated, and speech reception threshold testing only as indicated. I would include word recognition testing, starting with the 10 most difficult words first. Using a 25-word list where the first word is the hardest word and the 25th word is the easiest can save more time. If you finish all of this testing in a matter of 20 to 30 minutes, you can spend 10 or 15 minutes evaluating auditory function beyond the ear, by performing speech-in-noise testing, or conducting an auditory processing screening if indicated.

Summary

Audiologic patient care should be evidence-based, compliant with clinical practice guidelines, accurate and efficient. Sit down with your colleagues and ask, "What tests do conduct in our clinic? "Are we using the right procedures with every patient? "Are we using the best procedures?", and, "Are we following accepted clinical guidelines?" Depending on how you answer these questions, you may modify your protocols. Efficiency and effectiveness should always be considered when you're putting together your test battery. The goal is to get the most accurate information as quickly as possible. The test battery should only consist of value added tests. If there are procedures that aren't contributing to the diagnosis or the management of the patient, then you are justified in not using them.

Questions and Answers

References

Citation

Hall, J.W.III. (2017, September). Rethinking your diagnostic audiology battery: Using value-added tests. AudiologyOnline, Article 20463. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com