Learning Outcomes

After this course, learners will be able to:

- Describe potential problems experienced by hearing aid users with care and maintenance of hearing aids.

- List reasons why considering ease of use of hearing aids is important.

- Describe why formative testing is useful and list results from formative tests described in this study.

Introduction

My grandmother was fit with hearing aids when she was in her 60’s, and she wore hearing aids successfully for over 30 years; in her 90s, she stopped wearing her hearing aids because she was no longer able to change the batteries and caregivers at the nursing home, where she lived the last years of her life, could not help with this task. It is not unusual that nursing home staff are untrained in the care and maintenance of hearing aids. Cohen-Mansfield and Taylor (2004) found that about half of the nursing home staff in their study, had no training in the care of hearing aids. Hearing aids require care to function properly and caring for hearing aids requires some knowledge. Examples of necessary knowledge include how to change wax filters, identifying the correct batteries, as well as removing and inserting batteries. The lack of nursing home staff trained to help residents with hearing aids means many residents are missing out on hearing. For my grandmother this meant missing out on conversation and going from being an outgoing person to withdrawing from interactions.

If my grandmother had gotten help maintaining her hearing aids and changing her batteries - or better yet, had rechargeable hearing aids that were easier to maintain - she might have been able to continue participating more actively at the nursing home. Studies indicate that easy handling matters more as we age (Meister et al., 2002). This is not surprising as handling hearing aids, both to change batteries and to troubleshoot problems, requires visual acuity and adequate dexterity (Solheim, 2017). Ease of use can make the difference between a successful and unsuccessful hearing aid user; it can also increase the hours of use (Solheim, 2017). Ease of use includes battery changes, placing aids in ears, and care and maintenance. McCormack and Fortnum (2013) reported that difficulty with battery change ranged from 4-62% in the studies included in their scoping review. The large range of reported difficulty is related to the inclusion criteria of each study’s participants. The study with the 62% rate of difficulty with battery changes was conducted in a nursing home (Cohen-Mansfield & Taylor, 2004). This study also found that 42% of participants had difficulty placing hearing aids in their ears.

It is reasonable that hearing aid design is based on universal design, meaning accommodating the diverse needs and abilities of users. It is, to some extent true that universal design is used in the hearing aid industry; however other interests such as bringing a new technology to the market first or making a hearing aid as small as possible, may trump universal design. In the design process of the first rechargeable custom hearing aid from GN Hearing, Custom by ReSound, universal design guided decisions from start to finish. Cooling (2022) describes the charger as “well thought out” and that you can “see the influence of some pretty sharp thinking here.” The charger is indeed well thought out, but rather than relying only on “sharp thinking” this well thought out design resulted from a process of iterative testing with users to ensure universal design. As Cooling puts it, it is “easy to use for anyone” even “with dexterity issues”. This paper describes the journey of creating a custom charger using universal design principles.

Getting to Know the Hassles of Hearing Aids

An initial step in designing the charging system for the new custom hearing aids was to interview current hearing aid users to better understand their needs, strategies for managing their hearing aids, and struggles with maintaining their hearing aids. Insights gained from the interviews were used to identify ways that the charger system might reduce hassles experienced by hearing aid users, preferably without creating new ones.

One memorable interview was with an older person with low vision in addition to hearing loss. Her vision loss meant she could not see the color markers on her hearing aids that tell the user which is right, and which is left. To be sure that she did not mix up her right and left hearing aids she created labels that showed her where to place each hearing aid in the case when she took them off, as shown in Figure 1. A potential benefit of a charger in addition to not needing to change and manage batteries, could be providing right and left orientation.

Figure 1. An interview participant with vision impairment showed her method for keeping track of right and left hearing aids when she was not wearing them. “V” stands for “venstre” and “H” for “højre”; left and right in Danish.

Initial Prototype Testing

The Hardware Design group at GN Hearing created four prototype chargers, shown in Figure 2. These prototypes were tested by eight current hearing aid users. This may seem like very few participants to make design decisions; however, informative studies that focus on finding usability problems, small sample sizes with targeted users may be used to get an idea of what works and does not work before testing again. In these small studies, it is essential that participants are representative of the users and include people expected to have problems with the designs tested (Francik, 2015).

Figure 2. Mock-ups of the 4 charger designs that were tested: from left to right bowl, standing, hanging, and sideways.

All eight test participants correctly placed hearing aids in the bowl charger, seven participants correctly placed hearing aids in the standing charger, six participants correctly placed hearing aids in the hanging charger and four participants correctly placed hearing aids in the sideways charger. One user remarked about the sideways charger “it seems like a difficult puzzle.” Hearing aids were removed with ease from all charger prototypes. Participants preferred the bowl placement overall, some of this preference appears to be driven by the comfort of being sure they are doing it right because there is only one possibility presented. Figure 3 below shows participant taking hearing aids out of the bowl charger. The second most preferred charger was the standing charger.

The top two concepts, bowl and standing, were selected for improvement. The following changes were made based on the test results.

Bowl

- Depth reduced

- Shape changed to oval to make hearing aid removal easier.

Standing

- Hearing aid lifted above the charger to make hearing aid removal easier

- Hearing aid rotated 45o to ease placement directly in the ears

Figure 3. Test participant in action testing bowl charger.

Revised Prototype Testing

Revised designs were tested by thirteen participants; four participants had reduced dexterity, and one had severely reduced vision. All participants could correctly place hearing aids in both chargers. Participants were also asked to place hearing aids in their ears. All participants easily placed the hearing aids in his/her ears from the standing charger, eleven easily placed the hearing aids in his/her ears from the bowl charger, one person struggled, and one participant required assistance to place the hearing aids correctly in his ears from the bowl charger.

Test participants were asked about their charger preferences. Eight preferred the standing charger, four preferred the bowl charger and one person did not have a preference. Preference for the standing charger concept was based on three things: ease of removal from charger, ease of orientation for placement in ear and looking more correct/neat in the charger. Six people commented on the charger making it easier to correctly place the hearing aid in their ear. A participant who currently wears ITC hearing aids described the standing charger as an upgrade from his current solution even without the charging capability because it correctly oriented his hearing aids for placement in the ears. Participants who preferred the bowl charger concept based their preference on ease of putting the hearing aids in the charger.

Several participants without dexterity issues speculated about which charger would be easier to use when or if they had poorer dexterity or for someone else with poorer dexterity. In these imagined scenarios, both prototypes were chosen. However, these imagined future selves and their predicted ease of use did not match up well with the results from the people with the greatest dexterity or vision loss problems included in the testing. This highlights the importance of including a diverse test group rather than just guessing how people with different abilities might perform tasks and what they might prefer.

The results surprised the project team, who expected the bowl charger to be the easiest to use. If one only considers correct placement of the hearing aids in the charger, the bowl charger is the easiest to use. However, when the whole solution is considered, the standing charger had the additional advantage of helping users get the hearing aids correctly placed in their ears. Getting the hang of placing hearing aids correctly in the ear takes time for some hearing aid users, and in some cases, they continue to need help with placing the hearing aids in their ears correctly.

Based on these results, the standing charger concept was chosen, despite the extra complexity and cost of designing and manufacturing it. The additional complexity and cost are due to custom-made ‘inserts’ for the hearing aids to be placed in for charging. This decision was made because it was best for users.

Revising and Improving Standing Charger

After the selection of the standing design, the implications of this design choice were considered. One of the considerations was that the custom-made insert had nooks and crannies where ear wax could get stuck. Studies indicate that most hearing aids are contaminated with at least one bacterium, and many have more than one, so cleaning hearing aids and inserts is essential to avoid infection (Sturgulewski, 2006; Ahmad, 2007).

Due to the need for easy cleaning, removable inserts were required. Good design principles also dictated that the inserts should not only be removable, but also that removal and insertion was straightforward. The initial insert design was evaluated with seven participants. Inserts were correctly removed by six participants, four of the participants correctly put the inserts back in the charger without instruction and three required instructions to correctly place the inserts in the charger.

Based on these results, the inserts were updated to include arrows to show where to push to release them, and larger tabs were added to guide users in placing the inserts back in the charger. Nine participants were subsequently tested with these updates. Seven removed the inserts without instruction, and eight put the insert back in the charger without instruction. All were able to replace and remove the inserts on follow-up attempts without instruction.

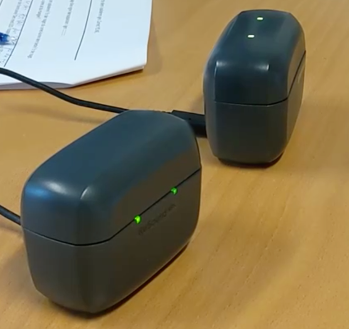

These nine participants were also asked about preferences for two different LED placements that would indicate charging status (see Figure 4). Five participants preferred split-line placement, three did not have a preference, and one preferred on top. Participants preferred split-line because it was easier to see LEDs when placed on a shelf or on a bedside table and because the LEDs can be turned away, for example, from the bed to avoid disturbing lights while sleeping.

LED blink patterns were also tested to ensure the meaning of the blinking was understood. Slow pulsing was understood by all to indicate charging. Just over half of the participants understood solid light to indicate a full battery. None of the participants understood fast blinking to indicate low battery, which it was intended to indicate. Based on these results, the fast-blink LED was eliminated, and the split-line LED placement was selected for the charger.

Figure 4. Examples of charger with LED located in the split-line (left) and on top (right).

Final Thoughts

The Custom by ReSound charger was developed in iterative process, meaning the design was tested many times. Final version is shown below in Figure 5. After each round of testing, the results were reviewed together with the design team and the design was updated to improve ease of use. After design updates were completed, the new design was retested to ensure the updated design worked. Diverse test participants, including people with reduced vision and dexterity, were included at all steps of this iterative process. Participants with reduced vision and dexterity are uniquely qualified to reveal design strengths and flaws and ensure a universal design is achieved. An example of a design strength revealed in testing is that the standing charger helped participants with reduced dexterity correctly place the hearing aids in their ears. The Custom by ReSound charger and hearing aid showcases the power of iterative testing and technological improvement to create a universal design that works well for all users. This charger allows users, like my grandmother, to become and to continue to be successful hearing aid users, even with reductions in vision and dexterity. For people with no visual impairments or dexterity problems this charger makes using hearing aids more hassle-free, which just might increase their wear time too.

Figure 5. Final charger: “Custom by ReSound”.

References

Ahmad, N., Etheridge, C., Farrington, M., & Baguley, D. M. (2007). Prospective study of the microbiological flora of hearing aid moulds and the efficacy of current cleaning techniques. The Journal of Laryngology and Atology, 121(2), 110–113.

Cohen-Mansfield, J., & Taylor, J. W. (2004). Hearing aid use in nursing homes. Part 2: Barriers to effective utilization of hearing AIDS. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 5(5), 289–296.

Cooling, G. (2022, June 30). GN announces launch of New Rechargeable Custom aids. Hearing Aid Know. https://www.hearingaidknow.com/resound-announce-launch-new-rechargeable-custom-hearing-aid

Francik, E. (2015). Five, ten, or twenty-five – How many test participants? Newsletter from Human Factors International. https://www.humanfactors.com/newsletters/how_many_test_participants.asp

McCormack, A., & Fortnum, H. (2013). Why do people fitted with hearing aids not wear them? International Journal of Audiology, 52(5), 360–368.

Meister, H., Lausberg, I., Kiessling, J., Wedel, H. V., & Walger, M. (2002). Identifying the needs of elderly, hearing-impaired persons: the importance and utility of hearing aid attributes. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 259(10), 531–534.

Solheim, J., Gay, C., & Hickson, L. (2018). Older adults' experiences and issues with hearing aids in the first six months after hearing aid fitting. International Journal of Audiology, 57(1), 31–39.

Sturgulewski, S., Bankaitis, A., Klodd, D., & Haberkamp, T. (2006). What's still growing on your patients' hearing aids? The Hearing Journal, 59(9), 45–48.

Citation

Sjolander, M.L. (2023). Universal design makes “custom by resound” a pleasure to fit, charge, and wear. AudiologyOnline, Article 28463. Available at www.audiologyonline.com