Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Explain the benefits of in-app surveys.

- Identify the relationship between sleep behavior and tinnitus.

- Explain the importance of including sleep behavior in their tinnitus management battery.

Introduction

Every day, many of us wake up to the awakening sound of an alarm clock, hoping we feel refreshed and energetic after a good night’s sleep, but this is not always the case. It is generally recommended that adults get 7 or more hours of sleep per night for the best overall health and well-being (Watson et al, 2015). Unfortunately, 50 to 70 million adults in the US have a sleep disorder, with insomnia being the most common (American Sleep Association, 2018). For many people suffering from tinnitus, sleep is a major concern. They are left wishing they slept better through the night, and could get more sleep. In fact, it has been reported that 54% of people with tinnitus also have some type of sleep disorder (Fioretti et al, 2013).

What is Sleep?

A lot has been learned about the importance of sleep over the past few decades, and we are beginning to better understand how sleep and tinnitus perception are related. Sleep used to be viewed as being a more passive, dormant part of our lives. But decades of research have led us to our more current understanding that sleep is in fact very active and dynamic, and is crucial for daily functioning and overall physical and mental health. Sleep is dynamic because there is constant neural activity that produces neurotransmitters that influence when we are awake, falling asleep and in deep sleep states. Neurons located in different regions of the brain can ‘switch off’ signals that keep us awake, and allow us to fall into sleep.

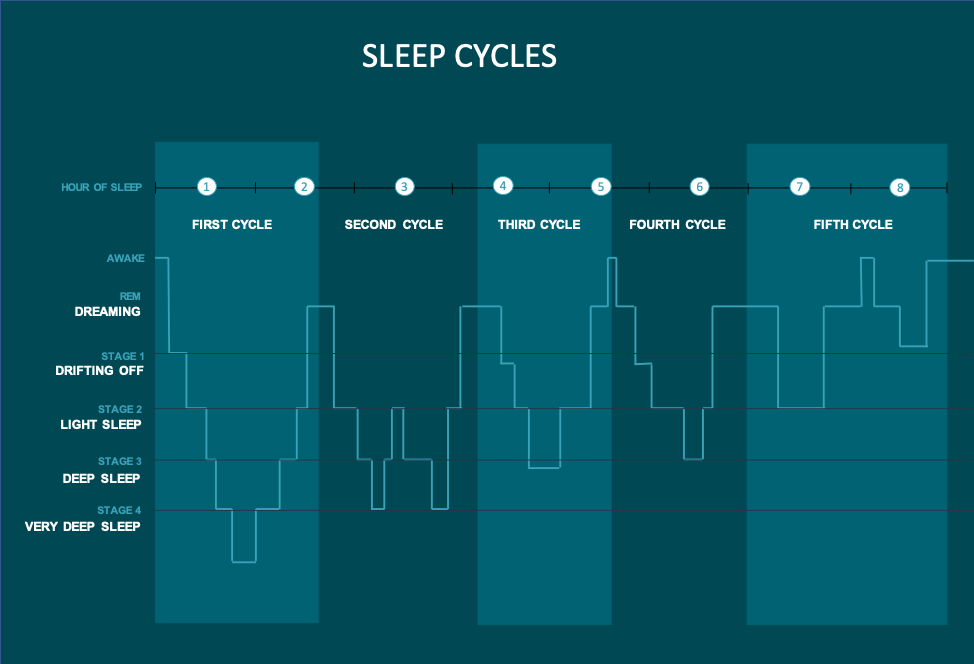

While sleeping, we typically go through five sleep stages. The stages are 1, 2, 3, 4 and Rapid Eye Movement (REM). The stages advance in a cycle, starting with 1 and finishing with REM sleep, then starting again with stage 1. On average, a sleep cycle takes 90-120 minutes, and people spend almost 50 percent of their total sleep time in stage 2, about 20 percent in REM and the remaining 30 percent in the other stages (Ogilvie, 2001).

Figure 1. Difficulties falling asleep due to tinnitus can interfere with the natural progression through the sleep cycles.

In Stage 1, we drift in and out of sleep, can have sudden muscle contractions and can be awakened easily. As we progress into the light sleep of stage 2, our eye movement stops and our brain waves start to slow down as we begin to fall into ‘deep sleep’. Stage 3 and stage 4 are prime ‘deep sleep’ stages, where the brain is almost solely producing slow, long burst brain waves, called delta waves. The delta band is a frequency band associated with brain synchronization, restorative sleep and sleep depth. It has been shown that reducing delta wave activity can lead to generalized discomfort, drowsiness, fatigue, mood swings, attention and memory disruptions, and daytime pain, which can be exacerbated by tinnitus (Lenz et al, 1999). Impaired attention and memory have also been reported in tinnitus. These disrupt effects may be a result of poor sleep behavior in combination with tinnitus, rather than produced by the tinnitus itself (Delb et al, 1999; Rossiter et al, 2006; Stevens et al, 2007).

Deep sleep is important for the release of human growth hormone, cell maintenance and the ability to process new information. In fact, increasing slow wave sleep has been shown to increase memory consolidation (Marshall et al, 2006). When bothersome tinnitus is compounded by poor sleep quality, people may lack the physical and mental health necessary to properly cope with their tinnitus. This in turn can negatively affect their ability to process and retrieve information and/or perform routine daily functions.

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, the last stage of the sleep cycle, increases our heart and breathing rates, puts our bodies into a temporarily paralyzed state, and we lose our ability to thermo-regulate, which is why some people can wake up very hot or cold from a deep sleep. As the night progresses, REM sleep intervals increase in length, while deep sleep intervals decrease.

A good night’s rest is important for performing everyday tasks and functions, as well as overall well-being. Sleep deprivation can lead to multiple behavioral deficiencies that affect’s one behavior throughout the day. For many people with tinnitus, they struggle with the early stages of sleep, resulting in difficulties falling asleep, and ultimately failing to reach the restorative deep sleep and REM stages. These disruptions in sleep quality can compound the effects they may already be experiencing from the tinnitus.

Tinnitus and Sleep

Multiple studies have shown that more than 50% of those suffering from tinnitus, experience either poor sleep quality, or have an actual sleep disorder (Fioretti et al, 2013; Koning, 2019). In fact, almost every tinnitus questionnaire, such as the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI), Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire (THQ), and others, ask at least one question having to do with tinnitus and its effects on sleep behavior. Additionally, insomnia and sleep disturbances have been shown to have greater influence on people who rate their tinnitus as being more severe, and annoying (Fioretti et al, 2013; Alster et al, 1993). It also appears that the actual level, or loudness, of the tinnitus plays a role in sleep behavior. Koning (2019) showed that sleep quality can be improved by reducing the perceived intensity of the tinnitus. Although there appears to be a strong link between tinnitus perception and sleep behavior, the cause and effect of the relationship are still not fully understood.

Crönlein et al (2007) looked at this more closely, by studying two groups of patients with insomnia, one group with tinnitus and one group without tinnitus. They found no difference between the groups on sustained attention tasks, subjective daytime tiredness, and depression rating scores. Although no difference was found between the two groups, insomnia and sleep disturbances clearly showed a negative impact on performing daily activities and tasks for both groups. Although it is difficult to decipher if sleep disruptions lead to increased tinnitus perception, or vice versa, it is clear that sleep disturbances can further negatively impact one’s quality of life, in addition to the tinnitus. This should be considered when addressing your tinnitus patients, and if they present with sleep disturbances, sleep therapy should be considered as part of a comprehensive tinnitus management program.

Sleep Behavior Recommendations

Although many people with tinnitus report having difficulty sleeping, very few actually seek a formal sleep evaluation (Alster et al, 1993). This could be for a variety of reasons. First, sleep evaluation is not part of most formal tinnitus management protocols, and with so few Hearing Care Professionals offering tinnitus management services to begin with, even fewer consider recommending a sleep evaluation. In addition, formal sleep evaluations are typically not designed with tinnitus in mind. Often it is up to the Hearing Care Professional to bridge the two together and make the recommendation for their patient.

Regardless of whether a sleep evaluation has been done, there are many tips for achieving better sleep, and with daily practice, these can help many people sleep more comfortably and undisturbed through the night.

Eating and Drinking:

- Avoid or minimize alcohol just prior to bedtime

- Avoid heavy meals just prior to bedtime

- Avoid caffeine or nicotine-based products prior to bedtime

Relaxing:

- It is not recommended to exercise before bedtime

- Use relaxation techniques, like breathing exercises or imagery prior to bedtime

- Listen to sounds that are relaxing and soothing

Sleep Behavior

- Avoid long naps during the day

- Create a sleep routine

- Go to bed at the same time each day

- Get up in the morning at the same time

Sleep Environment:

- Keep the room a constant, comfortably cool temperature

- Minimize light stimulation when going to sleep

- Play constant low-level sound throughout the night (for example, white noise or ocean waves sounds)

Using low level sound that is similar in frequency to delta waves (e.g. ocean wave-like rhythms) has been shown to help increase delta wave activity (Gartenburg, 2018). In addition to selecting sounds similar in spectral content to delta waves, sounds should also be selected based on what the individual finds most acceptable and helpful. Using irritating or unwelcomed sounds can have the reverse effect, and prohibit falling asleep.

Sounds while sleeping can be delivered through a variety of media. The most common are playing sounds through sleep buds, sleep pillows and/or external speakers, such as Bluetooth™ speakers. Many users even report using the speakers directly from their mobile devices, such as their smartphone or tablet. There are advantages and disadvantages of each medium.

For example, playing sound through sleep buds/ear buds, much like hearing aids can create physical discomfort while sleeping, and/or restrict the ability to hear environmental sounds due to the ear occlusion of the buds. For some, this trade-off may be worth it if it helps reduce their tinnitus and helps them fall asleep more easily. This is why it is important to consider multiple factors when recommending the correct device for better sleep behavior. In the next section we will discuss results from a ReSound Relief in-app survey, which gave us greater insight into how users of the app incorporate it into their sleep behavior.

ReSound Relief In-App Survey and Analytics

To better understand the sleep behaviors of ReSound Relief users, and how these users interact with the ReSound Relief app in regards to sleep behavior, an in-app survey was conducted. In-app surveys offer users a chance to provide voluntary and anonymous information over a defined period of time. In-app surveys also allow us to ask specific questions to a targeted audience, enabling us to better understand users’ behaviors and preferences.

Over an eight-week period, 3458 unique responders provided feedback to seven in-app survey questions pertaining to ReSound Relief and sleep behavior.

- Aside from tinnitus management, what is your primary purpose for using ReSound Relief?

- Do you have trouble falling asleep?

- What time do you normally go to bed?

- When do you use the timer feature in ReSound Relief?

- How does ReSound Relief compare to other things you’ve tried for better sleep?

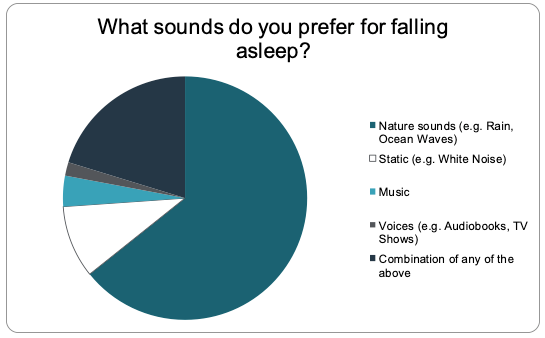

- What sounds do you prefer for falling asleep?

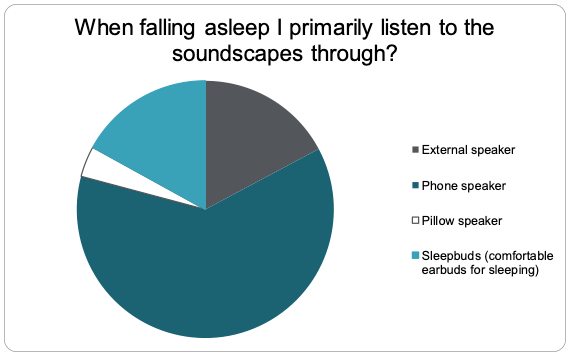

- When falling asleep, I primarily listen to soundscapes through?

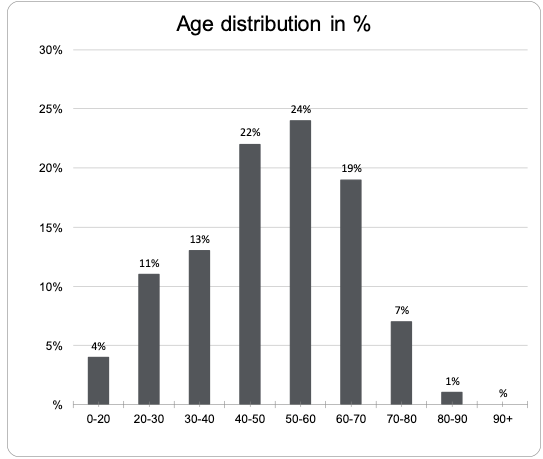

Of the survey responders, 51.4% were men, 45% women and 3.5% preferred not to say. 50% of users were under the age of 50, and 74% of users were under the age of 60. We also saw a 6% increase in younger responders (ages 20-40 years), compared to a previous survey in 2018 (Figure 2). The age distribution was in agreement with the age distribution of 470 tinnitus patients at a tertiary care clinic in Seoul, Korea (Swiahb, 2016). This suggests that a mobile app interaction, to collect user information, does not introduce an age-dependent selection bias that significantly skews towards a younger population, as might be presumed by using a modern mobile app-based survey.

Figure 2. Age distribution of people who responded to the in-app survey

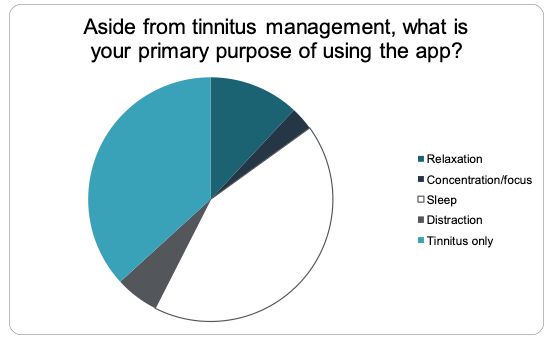

In regards to the primary purposes users engage with Relief, general sleep purposes (42%) were number one, followed by general tinnitus purposes (37%). In addition, 21% of users reported using Relief for purposes related to focus/concentration/distraction, which are all very common themes amongst people struggling with tinnitus. 71% of responders reported having difficulty falling asleep, indicating that many of the Relief app users, not only struggle with getting to sleep, but use Relief to help them achieve that goal (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Primary purposes of using the ReSound Relief app

It was also indicated that 92% of users normally go to bed sometime after 9pm, and 65% of users after 10pm. However, this does not indicate when users actually fall asleep, which is also valuable information that should be considered for future surveys and studies. Although bedtimes vary depending on a variety of factors, such as occupation, location, lifestyle and others, the average bedtime of ReSound Relief users in this study, fall in line with bedtime norms generally seen around the world. Notably, we also found that 93% of users reported using the timer feature in ReSound Relief solely for falling asleep. The timer feature automatically shuts off any audio from the ReSound Relief app according to a specified time by the user.

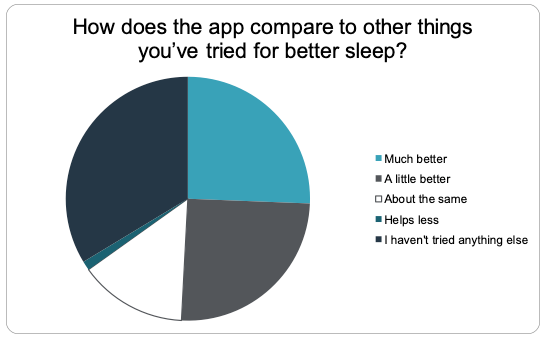

Understanding how ReSound Relief compares to other options users have tried to aid in better sleep behavior is also something we wanted to investigate. 51% of users reported that Relief is better than other tools they have tried, with only 1% saying it ‘helped less’ and 14% reporting it’s ‘about the same.’ Notably, 34% of responders reported they ‘haven’t tried anything else’ (Figure 4). Thus, it appears that for many of the survey responders, ReSound Relief serves as a more beneficial tool to aid in sleep behavior than other options they’ve tried. The fact that approximately one-third of responders have not tried other aids for better sleep supports ReSound Relief as an inexpensive, mobile and easily accessible tool for many people around the world.

Figure 4. Other options for helping sleep

Because sound therapy is an important part of tinnitus management, we also wanted to gather insights as to what sounds users prefer to listen to when they are falling asleep, and what means they use to deliver those sounds.

Nature-based sounds, such as Heavy Rain, Ocean Waves, Waterfall, etc. were preferred by 64% of responders. 10% preferred static sounds, such as white noise, and 4% preferred music-based files, such as Strings, Piano, Wind Chimes, etc. ReSound Relief users also have the ability to mix and layer up to five different soundscapes, if this is their preference. 20% of responders reported using a combination of mixed sounds to fall asleep to (Figure 5). Because sound therapy is not a one size fits all, this type of information from users can lead to app updates that offer more targeted and personalized soundscapes to help with better sleep behavior according to a user’s preference.

Figure 5. Preferred sounds for helping with sleep

Users also have a variety of products they can use to deliver the sound from the ReSound Relief app while going to sleep. As mentioned earlier, some of these are smartphone speakers, Bluetooth™ speakers and sleep buds. Using a the built-in speaker on a smartphone can significantly degrade the quality of the sound. While a Bluetooth speaker provides better sound quality, it may be intrusive to a sleeping partner’s auditory space while they are trying to sleep. Sleep buds or pillow speakers could be a viable option to provide adequate quality of the sound without disturbing a sleep partner.

From the survey, we found that 62% of responders reported playing sounds directly from their phone speaker. Equal proportions of responders reported using an external speaker (17%) or sleep buds (17%), to deliver the sound, and 4% reported using a pillow speaker. It is unknown from this survey why the majority of responders choose to play sound directly from their phone speaker, but some potential reasons could be convenience and portability. It may also be the case that some responders do not own other devices that can produce the sound. Acquiring more granular data of how different sound delivery methods may or may not benefit a user is something future research should aim to better understand, however the purpose of this survey was to get a general understanding of how users are delivering sound.

Figure 6. Sound delivery methods

Conclusion

Many people battling with their tinnitus, also struggle getting a good night’s sleep, which can result in a lack of focus, energy and degrading overall quality of life. Although it is challenging to untangle if sleep disruptions exacerbate tinnitus perception, or vice versa, it is clear that sleep disturbances can negatively impact one’s overall quality of life, in addition to the tinnitus. Currently, identifying sleep disturbances and recommending sleep evaluations is not commonly practiced in the hearing healthcare industry. Hopefully that will change as we collect more data to better understand the relationship between tinnitus and sleep. In the meantime, there are many helpful tips and exercises available, such as ReSound Relief, for your tinnitus patients who are struggling to get a good night’s sleep.

References

Al-Swiahb, J., & Park, S. N. (2016). Characterization of tinnitus in different age groups: A retrospective review. Noise & Health, 18(83), 214.

Alster, J., Shemesh, Z., Ornan, M., & Attias, J. (1993). Sleep disturbance associated with chronic tinnitus. Biological Psychiatry, 34(1-2), 84-90.

American Sleep Association. (2018). Sleep and sleep disorder statistics. Retrieved from https://www.sleepassociation.org/about-sleep/sleep-statistics/

Crönlein, T., Langguth, B., Geisler, P., & Hajak, G. (2007). Tinnitus and insomnia. Progress in Brain Research, 166, 227-233.

Delb, W., D’Amelio, R., Schonecke, O., & Iro, H. (1999). Are there psychological or audiological parameters determining tinnitus impact? In J. Hazell (Ed.), Proceedings of the 6th International Tinnitus Seminar (pp. 446–451). London: The Tinnitus and Hyperacusis Centre

Fioretti, A. B., Fusetti, M., & Eibenstein, A. (2013). Association between sleep disorders, hyperacusis and tinnitus: evaluation with tinnitus questionnaires. Noise and Health, 15(63), 91.

Gartenberg, D. (2018). The brain benefits of deep sleep – and how to get more of it. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1U2qMRGihGgwebsite

Koning, H. M. (2019). Sleep Disturbances Associated with Tinnitus: Reduce the Maximal Intensity of Tinnitus. The International Tinnitus Journal, 23(1), 64-68.

Lentz, M. J., Landis, C. A., Rothermel, J. Shaver, J. L., & Shaver, J. L. (1999). Effects of selective slow wave sleep disruption on musculoskeletal pain and fatigue in middle aged women. The Journal of Rheumatology,26(7), 1586-1592.

Marshall, L., Helgadóttir, H., Mölle, M., & Born, J. (2006). Boosting slow oscillations during sleep potentiates memory. Nature, 444(7119), 610-613.

Ogilvie, R. D. (2001). The process of falling asleep. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 5(3), 247-270.

Rossiter, S., Stevens, C., & Walker, G. (2006). Tinnitus and its effect on working memory and attention. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 150.

Stevens, C., Walker, G., Boyer, M. and Gallagher, M. (2007). Severe tinnitus and its effect on selective and divided attention. Int J Audiol, 46, 208.

Watson, N. F., Badr, M. S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D. L., Buxton, O. M., Buysse, D., ... & Malhotra, R. K. (2015). Consensus Conference Panel. Joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion. Sleep, 38(8), 1161-83.

Citation

Piskosz, M. (2020). ReSound Relief in-app survey: understanding how people with tinnitus use the app to manage sleep behavior. AudiologyOnline, Article 26808. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com