Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Describe the different components and descriptions of the FDA OTC hearing aid regulation.

- Describe some fitting issues that could work against successful OTC hearing aid use and benefit.

- Review some research that suggests that consumers might be able to fit themselves okay with OTC products.

- Describe how the HCP could implement sales and service of OTC hearing aid products.

Introduction

It was no secret to anyone that the talk of the hearing aid world in 2022 was the introduction of over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids. The buzz ranged from hearing aid companies hustling to develop products and marketing strategies, hearing care professionals (HCPs) wondering if their livelihood would be challenged, to consumers questioning if these new “bargain” products were for them. This all led to a flood of articles and comments on the topic from the manufacturers, professional organizations, the lay press, and audiology internet sites, not all of which was totally accurate. And of course, the “buzz” continued in 2023, as OTC hearing aids were mentioned by President Biden in his State of the Union address on February 7th.

In this Research QuickTakes Volume 5, we’ll provide some background regarding the underlying concept of OTC hearing aids, the basic technology, some initial concerns, the general fitting process, some tips for the hearing care professional (HCP), and how this new category might fit into the offerings of a typical hearing aid dispensing practice.

V5.1: All About the New Product Category

With all the press concerning the introduction of OTC hearing aids, one would think that this new category was suddenly thrown upon us. As reviewed by Powers (2022), this is far from the case:

- Serious discussions regarding the need for access and affordability of hearing aids for the general public began back in 2009 at an NIH conference.

- The topic later was picked up by the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, and then by the National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM). In 2016, the latter group issued a set of 12 recommendations concerning the OTC product.

- The NASEM recommendations led to the introduction of the over-the-counter hearing aid act by Senators Grassley and Warren in 2016. It was passed and signed into law by President Trump in 2017, requiring the FDA to have guidelines in place by August 2020. The pandemic, however, caused a delay.

- In October 2021 the FDA released the draft regulations with a 60-day comment period. Over 1000 comments were submitted.

- After five years of waiting, the 200-page document was finally filed on August 16, 2022, at 8:45 am (EDT), and went into effect on October 17, 2022.

New Hearing Aid Categories

In the document, the FDA described two different new types of OTC products. Both categories will have the same set of required device performance standards; electroacoustic test data according to ANSI/CTA-2051:2017. What we’ll call the “basic” pre-set OTC is defined as: air-conduction hearing aid for mild-to-moderate hearing loss that includes tools, tests, or software to allow the user to control or customize the device. These products have minimal user controls, and many do not have Bluetooth streaming or rechargeability. For example, The Sony OTC product in this category selects a pre-set gain curve based on the consumer’s responses to various chirps, delivered through the accompanying app. With the app, the patient has the basic controls of volume (~10 dB) and a ~15 dB range of treble control.

The second category of OTC products is similar, but includes more patient-controlled adjustments, and accordingly is labeled “self-fitting OTC.” It further is defined as: integrates user input with a self-fitting strategy, that enables users to independently derive and customize their hearing aid fittings and settings. Early models reveal that these products likely will also have Bluetooth streaming and rechargeability. It is required that this more advanced self-fitting products have FDA pre-market approval documentation, referred to as 510(k), a procedure that often requires clinical efficacy research. While the landscape changes rapidly, at this writing it appears that at least 5 or 6 manufactures already have gone through the 510(k) process with their self-fitting OTC products, with probably several more by the time you read this. We expect that these products will have a higher price tag than their basic OTC counterparts.

To help avoid confusion, the FDA assigned a new prefix to what we have simply called “hearing aids” in the past—in the FDA-world they are now called prescription hearing aids, and as always, only can be dispensed by a licensed professional. The term “prescription” has the potential to cause confusion among consumers and licensure boards, something we’ll address later.

Other Related Products

A category that still is around is the Personal Sound Amplification Product, commonly referred to by the acronym PSAP (pronounced “Pee-Sap”). The FDA defines these devices as sound amplifiers, used to increase sounds in certain environments for non-hearing-impaired consumers (e.g., used for hunting, bird watching, listening to a lecture with a distant speaker, etc.). They are not intended to compensate for hearing impairment, are not medical devices, and therefore are not subject to the FDA’s medical device requirements. Anyone who listens to television commercials, visits eBay, or surfs the internet of course knows that many of these PSAPs are being advertised and sold as hearing aids. Will some of the higher-end PSAPs move over into the OTC category? Maybe.

Another related category which has become a market presence in recent years are “hearables,” which are a sub-set of what we call “wearables,” which are defined as body-worn computers (Kemp, 2022; Hunn, 2014). Hearables have many forms and function, but a typical example related to our current OTC topic would be wireless earbuds that potentially can provide listening assistance in difficult speech-in-noise situations. You could call a hearable a PSAP, and they certainly are available over-the-counter. The hierarchy of current products is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Hierarchy of hearing aid related products following the 2022 FDA ruling.

Direct-To-Consumer

Finally, to add to the confusion, one more term related to hearing aids that has been used in recent years is Direct-To-Consumer (DTC). This, however, is a delivery model, not a product. Consider that today we have DTC hearables, PSAPs, and OTCs. If we stretch the definition a little, we could say that we even have DTC prescription hearing aids, as there are companies that mail prescription hearing aids to the consumer, which are then fitted remotely by a licensed professional. And, you can buy a prescription aid directly from eBay, though not the way it is supposed to work. We suspect that as the OTC market grows, we’ll hear less about DTCs, although the terminology gets confusing, at least in the early stages, as most OTCs will be DTCs (i.e., purchased online rather than in stores).

Intended Candidates for OTC Products

To some extent, OTC hearing aid candidacy is determined by the output restraints of these products, set by the FDA. The maximum output levels (peak 2-cc coupler) are 111 dB SPL for linear processing and 117 dB SPL for devices with input compression. There is no restriction for gain, although indirectly this will be controlled by the maximum output. Also, our guess is that gain often indirectly will be controlled by feedback—that is, maximum gain probably will not be possible. This is because, for the most part, we will have OTC hearing aid users with less-than-ideal ear coupling, and in many cases, using a product with a feedback reduction system (if any) of poorer quality than what we have become accustomed to in modern hearing aids (which often allows for an additional 15-20 dB gain when activated). The regulations do allow the manufacturer to provide a physical volume control on the device or a user control via an app.

The regulations state that the intended candidates are individuals with self-perceived mild-to-moderate hearing loss and who are over 18 years of age. Of course, as the name suggests, these products are sold “over-the-counter,” meaning that someone with a profound hearing loss could buy them, someone with normal hearing could buy them, and a parent could buy them for their one-year-old hearing-impaired toddler—something that, according to audiology social media pages, already has been reported as happening.

Also, note the key wording of self-perceived hearing loss—in the spirit of accessibility and affordably, no hearing test is required. We suspect that for most of the basic OTCs, the app will have some rudimentary “listening task,” the gain of the product will be determined from the results of this measure, and a pre-set (likely conservative) algorithm will be employed. The self-fitting products of course have a “back-up” strategy, assuming that consumers are good at fitting themselves—a topic we’ll discuss in the next section of this paper.

OTC Products and Distribution

At this early stage it is difficult to predict what products will be available and who will be the manufacturers. This is particularly true for the basic-OTC product, which does not require a pre-market 501(k) filing. We suspect that some products known today as “DTC PSAPs,” will move over to the OTC channel. They of course would have to meet the FDA electroacoustic requirements. If there is no policing of these products, however, many will simply skip the FDA requirements and “live on” in the DTC world.

What we are seeing early on, which makes good business sense, is that hearing aid manufacturers are partnering with well-known consumer electronics brands. These include Demant and Phillips, Sonova and Sennheiser, ReSound and Jabra, Nuheara and Hewlitt Packard, and WSAudiology and SONY. Stores that already have announced that they are selling OTC products include Best Buy, Walmart, Sam’s Club, Walgreens, CVS, to name some of the well-known leaders. In Iowa, one can even purchase OTC hearing aids at Hy-Vee grocery stores! Early sales reports, however, suggest that the majority of products from these retail outlets are being sold online, not in the stores themselves. Somewhat ironic, given that “access” was one of the leading factors for establishing the OTC category.

OTC FDA Ruling and State Laws

There are a few issues to consider regarding how the new OTC product category interacts with individual state regulations (Pilch, 2023).

- The FDA rule clearly outlines that states may not restrict or interfere with commercial activity related to the OTC product, which includes: servicing, marketing, sale, dispensing, use, customer support or distribution.

- Under the final rule, the FDA is repealing the requirement for a medical clearance for a prescription hearing aid. States, however, may choose to keep this in place.

- The FDA ruling stated that states that provide for a reasonable warranty or return period for hearing aids would likely promote, rather than restrict or interfere with commercial activity involving the OTC product.

- For prescription hearing aids, state licensure for the sale remains the same, but the FDA ruling states that an individual state cannot require a seller or dispenser of OTC-only hearing aids to have special licensing.

OTCs and the HCP

Even though we had 5-year advance notice that OTC hearing aids were coming, that didn’t deter a flurry of comments on HCP audiology social media when the document officially arrived in October 2022. Comments spanned the whole gamut from “This is the end of our profession” to “This is our time to shine!” Interestingly, the possibility of OTC hearing aids really isn’t anything new, and in fact goes back 20 years. In 2003 audiologist Mead Killion petitioned the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to establish a category of hearing aids that could be sold to adults in drug stores and other retail outlets, rather than being available only through licensed dispensing professionals. Sound familiar? The petition was rejected by the FDA based on the sanctity of the “required” medical evaluation—rather weak grounds given that consumers so routinely would sidestep this procedure by signing a waiver.

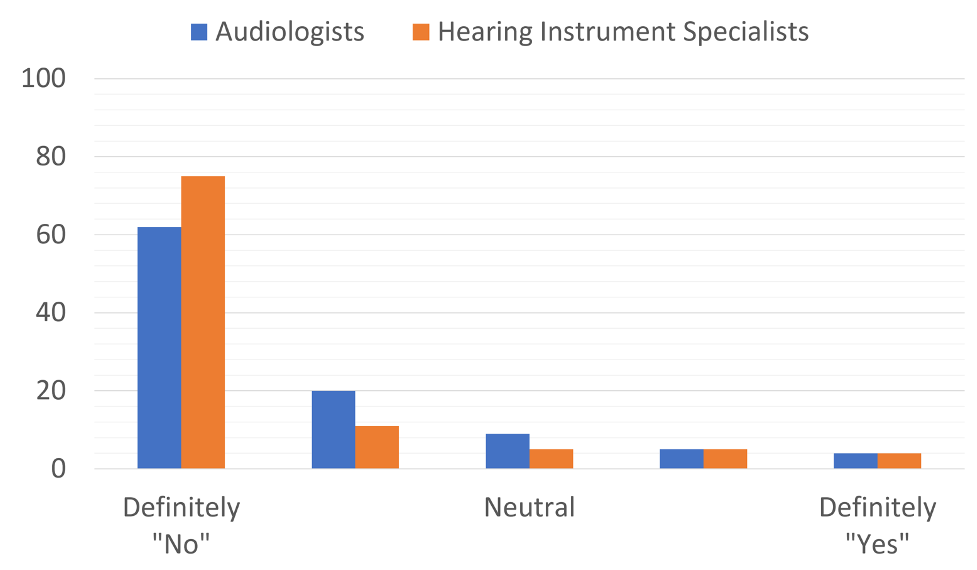

As also true today, the notion of OTC hearing aids generated considerable discussion, prompting The Hearing Journal to include questions on this topic in their 2003 dispenser survey, which generated 753 HCP respondents (75% audiologists) (Kirkwood 2004). We’ll take a glimpse back in time with Figure 2, which shows the results for the question “Should the FDA approve the proposed category of over-the-counter hearing aids for adults?” As clearly shown in Figure 2, HCPs strongly rejected the notion, by an 8 to 1 margin. The leading reasons for opposing the OTC category were:

- Dissatisfaction with OTC hearing aids would discourage people from ever going to a professional for help.

- They would not be of significant benefit to consumers.

- Medical conditions would go undiagnosed.

Figure 2. Response to question posed to HCPs ~20 years ago: Should the FDA approve OTC products?

Fast forward to 2022. The HearingTracker conducted a survey, where HCP respondents (n=730) rated different factors regarding the impact of OTC hearing aids (Bailey, 2022). The four leading concerns were:

- Consumers will struggle to identify and address common problems (like moisture and wax issues).

- Consumers who purchase OTC hearing aids will not be educated on realistic expectations.

- Consumers who purchase OTC hearing aids will not be educated on effective communication strategies.

- Consumers will miss medical red flags and fail to have pathologies diagnosed and treated in a timely manner.

In the same survey, 26% of HCPs stated that they plan to sell OTC devices at their clinics/practices or via their websites; 55% stated that they plan to provide support for patients who have purchased OTC devices elsewhere, with only 19% deciding not to sell or service OTC products. As mentioned earlier, there are some interesting licensure issues related to the OTC document. One of them is related to the term “prescription,” which in state licensure laws is reserved for physicians—the FDA issued a clarification statement on this topic in October, 2022, and it appears the issue has been mostly resolved.

Another issue is that the FDA did not mandate that OTC manufacturers have a return privilege. State licensing requirements for HCPs, however, do require both a return privilege and a trial period, placing HCPs who choose to sell these devices at a disadvantage, compared to other retail outlets. There are also many questions regarding how the OTC product will be viewed by insurance companies. Same as a prescription aid? Or, maybe only pay for OTC products? Or, the patient receives a “bonus” if they buy OTC? Stay tuned.

In Summary

We suspect that as time moves along, several new products will be introduced, the “players” in the OTC channel will be more clearly defined, retail sites will increase, and many of the issues related to OTC hearing aid distribution will be resolved. As survey findings reveal, the majority of HCPs plan to be involved with HCPs for sales and/or service. In the following sections of this Volume of QuickTakes, we’ll look at the projected success of these products, the technology and fitting procedures, and offer some guidelines for those who want to be involved in this new product category.

V5.2: A Good Fitting Without the Help of a Professional?

So, now that these products are available, what’s the probability that they will be of significant benefit for the hard of hearing? Already, OTC hearing aid manufacturers are publishing claims such as “provides a 30% speech understanding improvement in the presence of noise,” and “clinically proven to be substantially equivalent to a professionally fit hearing aid”.

Hearing care professionals (HCPs), however, have expressed concerns regarding these products—many of these surround the issue of the resulting gain and output when an HCP is not involved with the fitting. What if the app-driven hearing test is wrong? What if the automatic “fitting” of the product is poor? Or, what if, with the self-fitting OTCs, consumers are not very good at fitting themselves? It’s reasonable to assume, that if for one reason or another, things do not go well, the consumer might become discouraged regarding amplification in general, and this very probably will delay their decision to try prescription hearing aids and a professional fitting.

For the OTC hearing aid products that currently are available, it appears that there are three slightly different approaches being used to determine the gain and output:

- A rudimentary listening task using an accompanying smartphone app will be performed, and based on these findings the product will select, from pre-set algorithms, the gain and output for a given patient. The patient will have the ability to raise and lower gain, and in some cases, make some changes to the frequency response.

- Following the listening test, the patient will have the option to listen to different pre-set algorithms, choose what they prefer. This option will remain available as customers use the hearing aids in the real world, Gain and some frequency response changes also will be available.

- Following the initial listening/hearing test, a pre-set algorithm will be assigned as a starting point. The patient will then be able to self-program from a large range of gain, output and frequency responses, much like an HCP would do with a prescription fitting with an entry-level product.

What these fitting approaches all have in common, is that there is a gain and output starting point, that is determined by the pre-fitting listening test. It’s important to consider how this might impact the final fitting. We probably should start, however, with what we would consider a “good” fitting—that is, what gain and output would we like to see following consumer adjustments?

The Desired Result

There has been considerable talk that when consumers start fitting themselves, the fitting will not be appropriate, which then begs the question . . . what is appropriate? Given the research of the past 30 years or more, it would be difficult to build an evidence-based case against a validated prescriptive method such as the NAL (current version NAL-NL2) or the DSL (current version DSL v5.0) (see Mueller, 2020, and Mueller et al, 2017, for review). The majority of research on this topic has compared the NAL algorithm to a fitting that has less gain than the NAL—often the proprietary fit of various manufactures. In general, these studies have shown that the NAL algorithm results in better laboratory speech recognition, improved outcomes on real-world self-assessment inventories, and has been preferred by the majority of patients (Mueller, 2020).

As mentioned, alternative approaches tend to under-fit, especially for soft inputs. This needs our attention, as research that has studied large samples of self-reported success with hearing aids (Hickson et al, 2014; n=160), indicated that only five factors were significantly associated, and only one of these factors related to the processing of the hearing aids: fit-to-target for soft inputs. Moreover, recent research on brain plasticity and cross-modal organization has revealed that when patients are under-fit from the NAL-NL2 prescriptive targets, desired plasticity is reduced (Sharma, 2021).

There is also the link between the use of hearing aids and cognitive decline (Dawes et al, 2019), and while it hasn’t been studied directly, it is reasonable to assume that the suggested positive “hearing aid effect” only will be present if audibility is adequate. It seems clear, therefore, that the goal of the OTC hearing aid fitting is no different than that of a prescriptive fitting—the result should be gain and that is consistent with validated algorithms.

NAL As The Starting Point

As we mentioned, most of the new OTC hearing aids will have at least some pre-set responses that will be provided to the patient. The patient will then have the option to alter gain, and usually frequency response, to at least some extent. Will the start-up response influence the patient’s final setting of gain and output? We think so.

While using a smart-phone app to self-fit hearing aids is a relatively new concept, self-fitting hearing aids have been employed for 15 or more years via products that were termed “trainable hearing aids.” Using the VC of the hearing aid, or a remote, the patient would make adjustments to gain (and in some cases frequency response) in the real world, the hearing aid would “remember” the changes that were made, and over time new gain parameters were stored. The range of potential changes was relatively large, +/- 16 dB in some studies, and gain was “trained” independently for different input levels (e.g., in theory, a patient could train gain up by 10 dB or more for soft inputs, without changing programmed gain for loud inputs). Regarding the starting point of the training, most studies on this research topic have used the NAL as the initial setting. Some examples include:

- Catherine Palmer (2012) conducted a self-fitting training study with 36 new hearing aids users, all fitted to the NAL-NL1; one group trained for one month, the other for two months. In general, after training, both groups ended up very close (within 1–2 dB) to the NAL-NL1 targets for average inputs. The Speech Intelligibility Index (SII) for soft speech was reduced 2% for one group, and 4% for the group that started training at the initial fitting—more or less consistent with the gain reduction applied in NAL-NL2.

- In a separate study (Mueller et al, 2014), participants (n=20; all bilateral wearers) were individuals who had used their current hearing aids for at least two years, reportedly were satisfied, but had been under-fitted relative to the NAL—an average error of ~10 dB for soft inputs, and ~6 dB for average-level inputs. All participants were re-fitted to the NAL-NL1 prescription and trained in the real world for several weeks. Following training, they did not train down to what they had been using, but rather, only 2–3 dB below NAL-NL1 targets. Again, consistent with the gain changes applied in NAL-NL2.

- Finally, in a trainable study conducted with the initial programming of the NAL-NL2 prescriptive method, participants trained for three weeks, and the results of the training were assessed for six different listening situations (Keidser & Alamudi, 2013). That is, the training was situation specific based on the hearing aid’s classification system; for example, a given participant could train increased gain for music, and decreased gain for speech-in-noise. For all conditions, the participants did tend to train down slightly from the NAL-NL2, but only by an average of 1-2 dB.

These and other studies suggest that if self-fitting starts with a fitting similar to that of the NAL, then the average patient-derived fitting also will be similar to the NAL. But what if the start point isn’t the NAL algorithm?

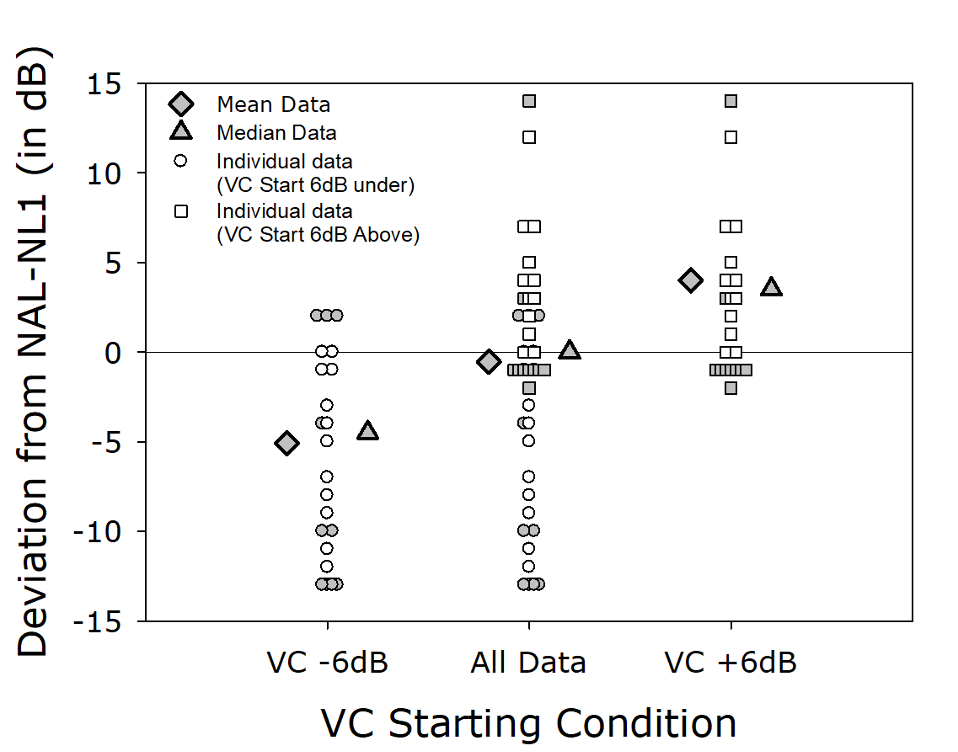

To examine this question, Mueller et al (2008) in a cross-over design, fitted 24 individuals with trainable hearing aids with two different start points: NAL+6 dB and NAL-6 dB. When the participants were fitted to NAL+6 dB, following training the average trained use-gain was NAL+4 dB. When fitted to NAL-6 dB, however, the average trained use-gain was NAL -5 dB (See Figure 3). That is, on average, the same individuals chose to use 9 dB less gain simply because of the reference point of the initial start-up value. This suggests, that if we indeed believe that a “good” fitting is at or near the NAL algorithm, then it would be wise to use initial pre-sets corresponding to these values in the OTC products.

Figure 3. Deviation (dB) from the NAL target following training. Using a cross-over design, experienced hearing aid users with trainable hearing aids were given a start-point of either 6 dB above the NAL, or 6 dB below the NAL. Shown on the Figure are the resulting means, medians, and scatter of indidivual trained gain for each participant.

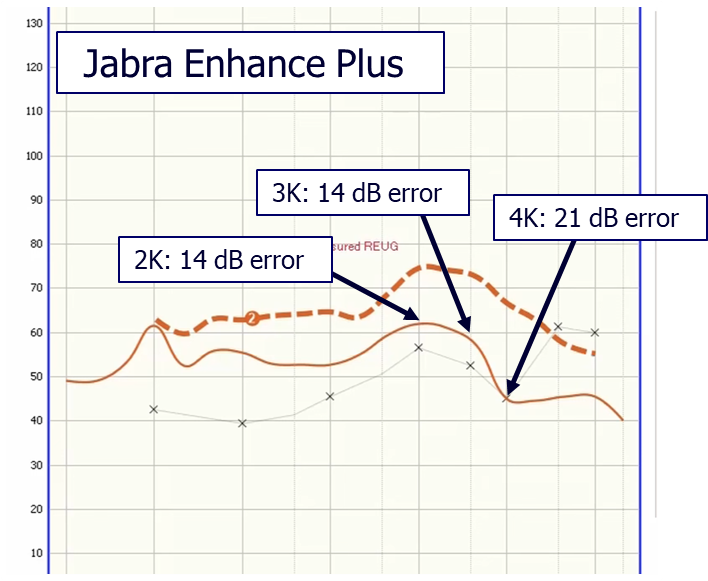

Are OTC pre-sets close to the NAL prescription? If the NAL algorithm is a good ending point (it is), and if we know that if you want to end there (we do), you probably should start close to this fitting rationale. Is that what OTC manufacturers are doing? There has yet to be a systematic study on this topic published, but we do have some anecdotal data from audiologist Cliff Olson (2023a). Shown in Figure 4, is the resulting pre-set real-ear output for the Jabra OTC product (compared to the NAL-NL2 targets) for an individual with a mild-to-moderate hearing loss, who used the app-based testing procedure of the Jabra. Note, that the pre-set gain results in large errors. Unfortunately, this is not unique to the Jabra. Olson showed similar results for the Lexie OTC product (2023b), and also for the Sony (Olson, 2022). Given this extremely poor starting point, how many potential OTC users will just assume that “hearing aids” don’t work, and not ever try to program a better setting?

Figure 4. Pre-set output for the Jabra OTC product following the app-based hearing test for an individual who had a mild-to-moderate hearing loss (see lower x-x tracing on chart for thresholds). Output compared to NAL-NL2 fitting targets, and degree of error noted.

Related Research Findings

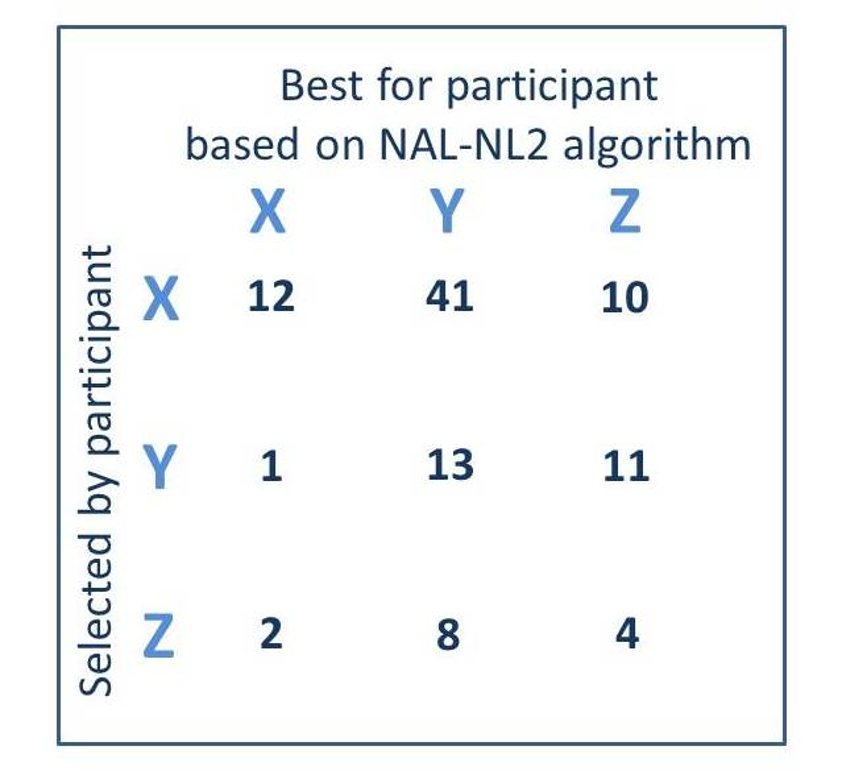

As we’ve discussed, the starting point for a fitting can influence the final gain selected by the patient. This leads us to question if the patient is a good judge of what fitting is best for them? Data from the Humes et al (2017) research can help us answer this. In this large study, participants were divided into three different groups (~50/group): 1) fitted to the NAL by an audiologist, 2) self-fitted by listening to three different pairs of pre-programmed hearing aids, and 3) a placebo group—fitted by audiologists to 0 dB gain.

When audiologists compared the pre-programmed hearing aids to the patient’s audiograms, they selected the hearing aids with the “medium” amount of gain for 61% of the 102 ears—See Figure 5. The patients themselves, however, based on listening tasks using the various pairs of hearing aids, only selected these same products 14% of the time, and rather, usually (62%) selected the pair of hearing aids with the least amount of gain. Across all three hearing aid categories, the audiologists and the patients were only in agreement 28% of the time.

Figure 5. A comparison of the hearing aids (X, Y, or Z) selected by the participants (read horizontally) vs. the hearing aids that would be deemed appropriate based on the NAL-NL2 fitting algorithm (read vertically). Each cell represents the totals (right and left) for the 51 participants fitted bilaterally.

All participants paid for their hearing aids at the beginning of the study, knowing that they could return them for credit at the end. Perhaps not surprising, only 53% of the participants who fitted themselves choose to keep the hearing aids, compared to 81% for those fitted by an audiologist. The most interesting finding of the study was that for the Placebo group, those who wore hearing aids with little or no gain for six weeks, 36% chose to keep their hearing aids!

WDRC Processing

There are research findings from ~20 years ago or more, suggesting that patients prefer gain less than the NAL. It is important to point out, however, that most of these studies were conducted using hearing aids with linear processing. As is commonly known, linear processing tends to make loud sounds too loud, and as a result patients will turn down gain, making it appear as if they prefer less gain than prescribed for average inputs.

Unfortunately, this outcome can still be problem today, as most manufacturer’s proprietary fittings use near-linear processing, even though the products themselves are WDRC capable. For example, Saunders et al (2015) found that on average (5 major manufacturers) the default fitting was ~5-10 dB below NAL targets for soft inputs, but 5-10 dB above NAL targets for loud inputs. Given the research supporting the development of the NAL targets, we would then expect patients with this fitting will turn down gain to make loud inputs “okay” (Mueller, 1999). This points out, that when self-fitting is employed in this new family of OTC hearing aids, it is critical that WDRC processing is used. But will some have linear processing?

We’ll close out this section with some older research related to patient-preferred gain, but it indeed was conducted using WDRC products, so has relevance to today’s instruments (Cunningham et al, 2001). Two groups of hearing aid users were initially fitted to the NAL, with the gain altered slightly based on loudness judgments. The resulting average REIG for both groups was ~2-4 dB below the NAL-NL1 prescribed gain—similar to what is now NAL-NL2. During the field trial, gain for the treatment group was altered according to the subjects’ request on five monthly post-fitting visits. No gain changes were allowed for the control group. At the end of five months, the resulting average gain for the treatment group for a 65 dB input was only ~5 dB! This was for a group that had mean PTAs of 26 dB at 500 Hz sloping to 58 dB at 4000 Hz, who obviously need considerably more gain than 5 dB.

What Does All This Mean?

The underlying goal of OTC hearing aids is to make amplification for the hearing impaired more accessible and affordable. These goals appear to have been accomplished, but what is the “price-to-pay” when it comes to a fitting that provides appropriate benefit and satisfaction. Is an “okay” $600.00 fitting better than an “excellent” $1200.00 fitting from a licensed professional? There are data to suggest that we certainly should be at least somewhat concerned regarding the ability of patients to fit themselves correctly—this not only involves the tech-savviness of the patient, but also their overall ability to decern what gain and output truly is best for them. Another factor relates to the products’ “automatic” settings that are provided by individual manufacturers—preliminary testing has shown that these pre-sets may be too conservative.

Fortunately, however, there are some research findings that suggests that things might be not as bad as we think, and we’ll be discussing some promising self-fitting findings in the next section.

V5.3: Some Encouraging Self-Fitting Research Findings

To this point, we have talked about some real concerns that patients who choose OTC hearing aids will not be fitted appropriately. But like most topics, there also are some research findings that suggest that maybe things will be better than we think.

Revisiting Earlier Data

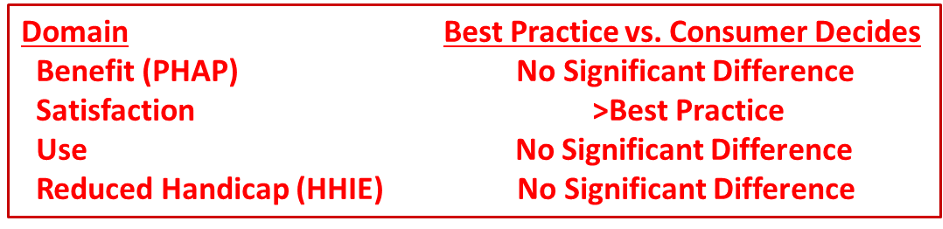

Earlier we discussed some of the findings from the large Humes et al (2017) study which compared “consumer decides” fittings to those fitted according to Best Practice. Specifically, we pointed out that when audiologists compared the pre-programmed hearing aids to the patient’s audiograms, they selected the hearing aids with the “medium” amount of gain for 61% of the 102 ears (See Figure 5). Recall that the patients themselves, however, only selected these products 14% of the time, and rather, usually (62%) selected the product with the least amount of gain. To be more precise, real-ear measures showed that the self-fittings had an aided SII (65 dB input) ~6-7% lower than the best practice fittings. It would seem that reduced audibility would have an effect on real-world benefit and satisfaction, but was that the research findings?

The comparison of the two different fitting approaches for several real-world measures are shown in Figure 6 (Humes et al, 2017). There was greater satisfaction for the features of the hearing aids when they were fitted via best practice, but note that there was no significant differences for benefit, use, or the reduction of the hearing handicap. This could lead one to conclude, that although the self-fitting group choose less audibility, the difference was not great enough to have a significant effect for many real-world domains of hearing aid use. The self-fitting skeptic, however, might say that the self-assessment questionnaires that were used simply are not sensitive enough to detect the differences that were present. This of course is why we are seeing an increased use of Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) in hearing aid research that involves a real-world component (Wu, 2017).

Figure 6. Summary of real-world outcomes for four different domains related to hearing aid use. (From the data of Humes et al, 2017)

We’ll also can go back to some other research that we discussed earlier. Recall that work by Catherine Palmer (2012) showed that when a large group of new users (n=36) were initially fitted to the NAL, after 4 to 8 weeks of training, on average, they remained fitted to the NAL. Our reason for previously reviewing this article was to point out that the NAL algorithm seems to be a good starting point. An interesting finding, however, was that at the conclusion of the study, in a blinded listening task, 2/3 of the participants favored their “trained setting.” We suspect that was because some of the participants preferred more gain than the NAL, and an equal amount preferred less gain than the NAL, and therefore the mean values did not change, but several individuals ended up with a preferred fitting following their field adjustments.

Self-fitting vs. Clinician fit

Another study has compared a group of individuals fitted with the same self-fitting hearing aids (Keidser & Convery, 2018). The participants conducted self-directed threshold measurements leading to a prescribed hearing aid setting, and fine-tuning, without the need for professional support. Participants consisted of 27 experienced and 25 new hearing aid users who completed the self-fitting process—some of the participants required professional assistance, resulting in 38 user-driven and 14 clinician-driven fittings. Following 12 weeks' experience with self-fitting products in the field, outcomes measured included: coupler gain and output, handling and management skills, speech recognition in noise, and self-reported benefit and satisfaction. Irrespective of hearing aid experience, the type of fitting (user- or clinician-driven) had no significant effect on coupler gain, speech recognition scores, or self-reported benefit and satisfaction.

For the participants who already were hearing aid users (n=27), the self-fitting was compared to their personal clinician-fit instruments. Users selected significantly more low-frequency gain when they fitted themselves. The conventionally-fitted hearing aids were rated significantly higher for benefit and satisfaction on some subscales due to negative issues with the physical design and implementation of the self-fit products. The authors concluded that with the right design and support, self-fitting hearing aids may be a viable option to improve the accessibility of hearing health care.

Goldilocks’ Procedure

A group of researchers, headed by Author Boothroyd, has conducted considerable research with the self-fitting of hearing aids over the past few years (Boothroyd & Mackerzie, 2017; Mackerzie et al, 2019; Mackerzie et al, 2020). They refer to their approach as the “Goldilocks’ Method”—getting the fitting “just right.” In general, their findings have revealed that the self-fitting approach can be successful.

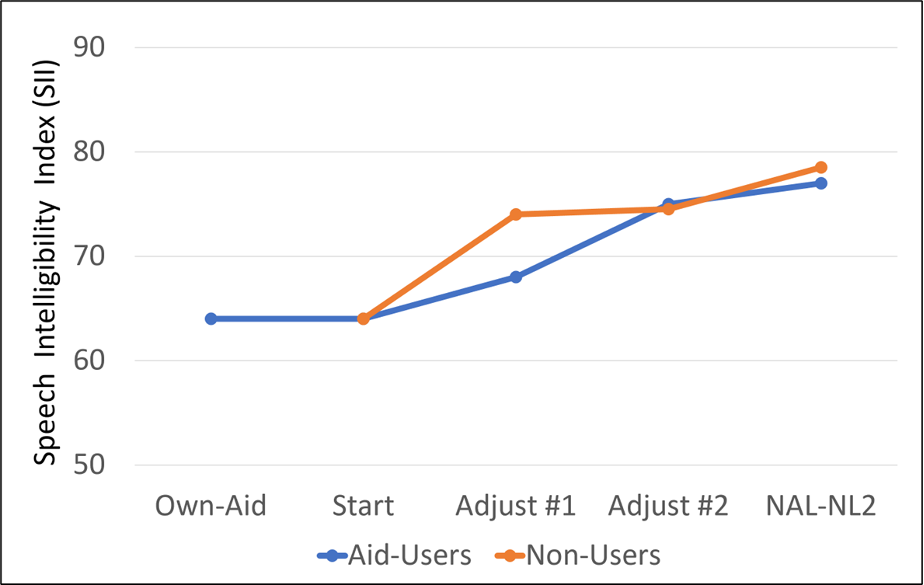

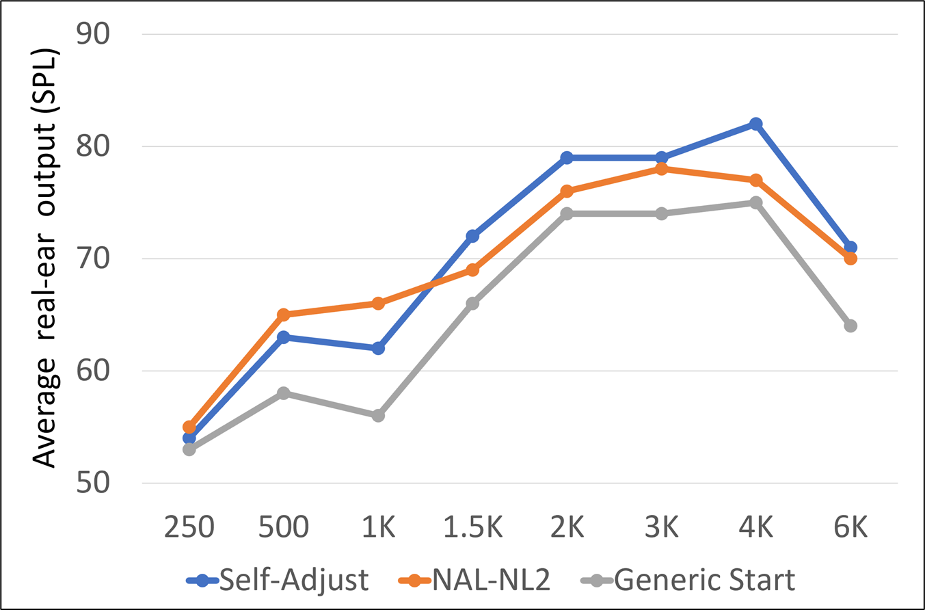

In one of their studies, a group of 26 individuals (13 of which were previous hearing aid users) with mild-to-moderate hearing loss, listened to prerecorded sentences. Starting with a generic level and spectrum, participants adjusted (1) overall level, (2) high-frequency boost, and (3) low-frequency cut. The participants adjusted the hearing aids for two trials and Speech Intelligibility Index (SII) was calculated following the adjustment; the generic starting condition provided outputs and SIIs that were significantly below those prescribed by NAL-NL2.

The SII findings are shown in Figure 7 (Mackerzie et al, 2019). Note that after the second adjustment, the SIIs for both groups were not significantly different from what was achieved with the NAL-NL2 prescription fitting. The authors selected a 60% SII as the target for good speech understanding. With the initial generic fitting, only 17 of the 26 participants (65%) met this SII criterion. The proportion increased to 23 out of 26 (88%) after the final self-adjustment.

Figure 7. Mean SII values for individuals conducting self-fitting compared to the average SII that would be obtain with an NAL-NL2 fitting (adapted from Mackerzie et al, 2019).

In a similar study from this group, using the Goldilocks approach while listening to recorded sentences with a sound-field level of 65 dB SPL (with multi-talker babble; + 6 dB SNR), 24 adults with hearing-aid experience adjusted the level and spectrum of amplified speech to their preference (Mackerzie et al, 2020). All participants started adjustment from the same generic response. A formal speech-perception test was conducted between repeated self-adjustments. The frequency-specific adjustments are shown in Figure 8, which on average were slightly above that of the NAL-NL2 prescription. Phoneme recognition for monosyllabic words was better with the generic starting response than without amplification and improved further after self-adjustment. The authors conclude that their findings support the value of completing more than one self-adjustment, but that their group-mean data did not indicate a need for threshold-based prescription as a starting point for self-adjustment (although, as shown in Figure 2, the generic starting point had a similar pattern to the NAL-NL2, and was only ~5 dB or so below this prescription for most frequencies).

Figure 8. A comparison of the average user-selected hearing aid output to the starting point and the NAL-NL2 algorithm.

The research conducted using the Goldilocks’ approach certainly is encouraging. It is difficult to determine, however, how this will relate to today’s self-fitting OTC products. Unlike the OTC pre-sets, the Goldilocks’ starting point, at least in some studies, was relatively close to the NAL-NL2. Additionally, adjustments were made listening to controlled, structured speech material in a laboratory. Will similar adjustments occur when listeners are self-fitting to random speech in real-world listening situations? And, will self-fitting OTCs have the gain and frequency-spectrum flexibility that was present in these research products?

The Bose Study

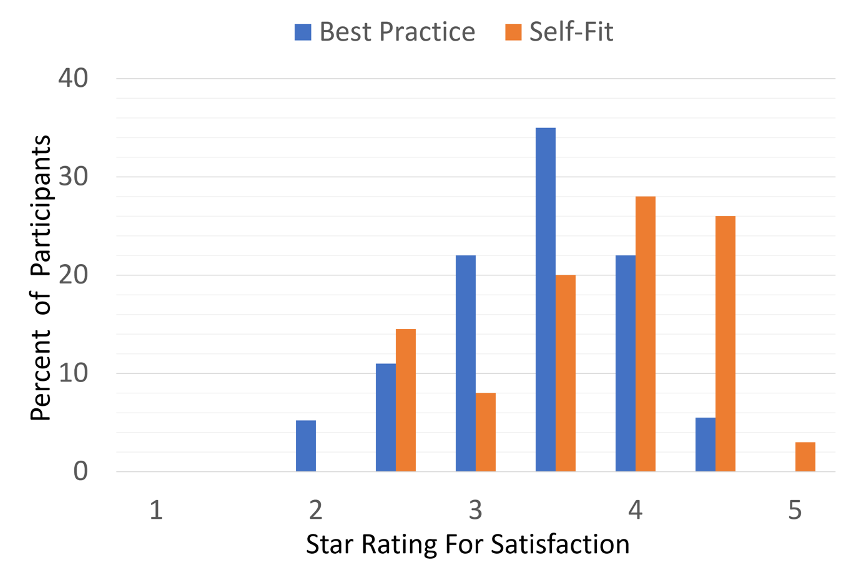

Perhaps the research that relates most directly to this topic is the study by Bose (Sabin et al, 2020), the results of which were then used to obtain FDA approval for a self-fitting product, a version of which is being sold online and in stores today. In this research participants used an interface with the hearing aid that allowed them to select their own gain and compression in each of 12 frequency bands. They were all first fitted using clinical best practices: audiogram, fit to NAL-NL2 target, real-ear verification, and subsequent fine tuning, and importantly, used the hearing aids fitted “correctly” for a week. Then, in their everyday lives over the course of a month, participants either selected their own parameters using this new interface (Self-fitting group; n = 38) or used the parameters selected by the clinician with limited control (Best Practices Group; n = 37).

What made this study unique, was that the initial position of the interface corresponded to 0 dB real-ear insertion gain (REIG) for all participants in the self-fitting group. The starting point of 0 dB REIG eliminates the self-fitting bias of starting at the NAL-NL2 algorithm that we discussed earlier.

For both groups, several measures were collected during the multiweek field use including selected gain values, sound quality assessments, and paired-comparisons between self-fitting and audiologist-selected settings. At the conclusion of the study additional self-assessments outcomes were administered, and also speech recognition-in-noise was conducted. A summary of the findings are as follows:

- A/B comparison. The participants also completed an A/B comparison with the original clinician-fit and their self-fitting. Although 31% of the ratings were “no preference,” when a preference was noted, it nearly always was for the self-fitting, 53% vs only 16% for the clinician fit.

- Outcome measures. The self-assessment benefit inventories used in this research were the APHAB and the SSQ12. There was no difference in benefit between the Best Practice and self-fitting groups for either of these measures. There also was no difference in aided speech-in-noise recognition, as measured using the QuickSIN. We need to point out, however, that the QuickSIN was conducted at 60 dB HL—the authors did not state the more important SPL values, but we would assume that they were ~72-75 dB, considerably louder than normally used for aided speech testing. We don’t know, therefore, if the under-fitting of gain for the self-fitting group would have had an impact on speech-in-noise understanding for more common listening situations.

Figure 9. Results of the “Five Star” ratings for those with the Best Practice fitting compared to the Self-Fit group (Sabin et al, 2020).

- A/B comparison. The participants also completed an A/B comparison with the original clinician-fit and their self-fitting. Although 31% of the ratings were “no preference,” when a preference was noted, it nearly always was for the self-fitting, 53% vs 16% for the clinician fit.

- Outcome measures. The self-assessment benefit inventories used in this research were the APHAB and the SSQ12. There was no difference in benefit between the Best Practice and self-fitting groups for either of these measures. There also was no difference in aided speech-in-noise recognition, as measured using the QuickSIN. We need to point out, however, that the QuickSIN was conducted at 60 dB HL—the authors did not state the more important SPL values, but we would assume that they were ~72-75 dB, considerably louder than normally used for aided speech testing. We don’t know, therefore, if the under-fitting of gain for the self-fitting group had an impact on speech-in-noise for more common listening situations.

In general, this study would suggest that if the hearing aids have the right tools to make the necessary adjustments, it’s possible that self-fitting will favorably compare to clinician-fit hearing aids, which was the conclusion of the authors. We have to remember, however, that the individuals who are selected to participate in these studies, often are much different than than the typical patient purchasing OTC products. For example, in the large Humes et al (2017) study, 49% of the 323 patients originally considered eligible to participate were eliminated.

Real-World Long-Term Studies

Given that the OTC product has only been available for a limited time, there are limited data regarding long-term benefit and satisfaction in the real world. One study, that to some extent sheds light on this is from Swanepoel et al, 2023. Technically, it isn’t an OTC study, as data was collected before the OTC category was established, but the DTC product used in the study is similar (or identical) to what is now an OTC product.

These authors compared hearing aid benefit and satisfaction using the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA). There were two groups, those fitted with the DTC product, and individuals who had purchased traditional hearing aids—data collected through the HearingTracker web site. The overall findings on the IOI-HA were no significant difference for overall hearing aid outcomes between the traditional hearing aid users and those using the DTC product. The authors concluded that the DTC/OTC hearing aid outcomes could provide similar satisfaction and benefit as hearing aids fitted through traditional channels.

We need to point out, however, that the DTC/OTC delivery model used in this study is not what is going to happen for most consumers who purchase OTC products. Company policy with the product used in this research, is that as soon as it was ordered, a professional contacted the individual and followed them through the process. The hearing testing was more advanced than with most OTCs, using in situ pure-tone audiometry, and then autofitting to the NAL-NL2. Remote support via video or audio calls was available, wearing goals were established, and rewards were provided based on participation and goal completion. It is reasonable to believe that all this easily could have boosted the IOI-HA ratings.

Health Locus of Control

One interesting area of health-care study which would seem to impact on the success of self-fitting OTC hearing aids is what is termed health locus of control (HLOC). HLOC refers to people's attribution of their own health to personal or environmental factors. Based on the results of self-assessment questionnaires, HLOC often is classified into three different dimensions: internality, powerful others, and chance. A patient’s locus of control is related to their self-efficacy. This is the belief that you can produce the result you want in a specific area—how much control you feel like you have over a situation. People with high self-efficacy for a task will most likely have an internal locus of control for success in that task.

Easy to see why HLOC can relate to self-fitting products. This has been studied to some extent in research that sought to identify factors that are associated with the ability to successfully set up a pair of commercially available self-fitting hearing aids and identify factors that are associated with the need for knowledgeable, personalized support in performing the self-fitting procedure (Convery et al, 2019).

Sixty individuals with hearing loss were provided self-fitting hearing aids. Half of the participants were current users of bilateral hearing aids; the other half had no previous hearing aid experience. The self-fitting procedure required participants to customize the physical fit of the hearing aids, insert the hearing aids into the ear, perform self-directed in situ audiometry, and adjust the resultant settings according to their preference. Forty-one (68%) of the participants achieved a successful self-fitting. Most importantly for our discussion here, of the 41 successful self-fitters, 15 (37%) performed the procedure independently. Those who needed help from an HCP were more likely than those who self-fit independently to have a health locus of control that is externally oriented toward powerful others. Otherwise stated, we can expect those patients with high self-efficacy and an internal locus of control to be the most successful with self-fitting. While in this study, the participants were not selected based on their HLOC, it is probable that many OTC hearing aid customers indeed have an internal HLOC, or they would not have chosen the OTC pathway.

What Does All This Mean?

As we’ve reviewed here, there is some research to suggest that self-fitting products will work okay, if the patients have the right tools. To some extent, we have cherry-picked articles that reached those conclusions. A better way to reach a conclusion of course, is to do a systematic review of all the published articles of interest, and this recently was done on this topic (Almufarrij et al, 2022). In most cases, a systematic review will provide the opportunity to combine the data of many studies, and to allow for an evidence-based decision with a high level of confidence. Unfortunately, in the portion of this review which compared Prescription Fitting to Self Fitting, only two studies were available, and for some comparisons, only one, the Bose study we reviewed above—which we should mention was an industry study specifically designed to showcase the Bose self-fitting system. Hence, it is difficult to draw any meaningful conclusions from this systematic review, and in fact, the authors concluded “the quality of evidence for the outcomes ranged from low to very low.”

Regardless of the success of the self-fitting approach, we know that many patients will purchase these instruments, along with the lower class of OTC products that are not self-fitting. It is reasonable, therefore, to discuss how the average HCP might consider the sales and service of OTC in his or her practice, which is the next section of this Volume of QuickTakes.

V5.4: Practical Issues Surrounding Sales and Service

As we mentioned earlier in this article, a 2022 survey revealed that about 70% of HCPs are planning on either selling OTC products directly, or servicing them for patients who buy them elsewhere (Bailey, 2022). In this final section of this paper, we’ll talk about the practical issues surrounding the fitting and/or servicing of OTC hearing aids in your practice. Let’s start with some general reasons why OTC hearing aids might be good for both the HCP and the consumer.

Affordability

It has been reported, that for some individuals, obtaining a pair of hearing aids is the 3rd most expensive purchase they will make in their lifetime. This probably doesn’t apply to too many people, but the fact is, the cost of pair of hearing aids does exceed the disposal income budget for many. For starters, consider that the (before-tax) median income for a family of two in the U.S. is only around ~$75,000, and much lower in several states. A pair of hearing aids for ~$600.00-$800.00 vs. a pair for ~$4000-$6000 could make a huge difference for many of these families.

Accessibility

For many, especially the poor, the elderly, and those living in rural areas, travel to an HCP office is difficult, sometimes impossible. One of the primary goals of the OTC hearing aid initiative was to make hearing aids more accessible. We already know, that these products will be sold at stores such as Walgreens and CVS. Research has shown that nearly 90% of Americans live within 5 miles of a pharmacy, and about 50 percent of the population lives within 1 mile of one.

Market Penetration

In the past decade, considerable research has emerged revealing the benefits of the use of hearing aids on quality of life. Positive associations have been found between hearing aid use and social isolation, physical activity, depression, balance function and cognitive decline, to name a few. It is reasonable to assume, that if hearing aids are more affordable and more accessible, the percent of hearing-impaired individuals using hearing aids will increase.

Public Awareness

As more players enter the OTC hearing aid market, we know we will be seeing more ads for these products on television, magazines, news sources and social media. Casual shoppers will be seeing shelves and/or racks of hearing aids in stores where hearing aids never appeared before. A lot of exposure. Yes, this advertising might encourage many to purchase the OTC product. But, it also will encourage others to start thinking about their hearing loss, and just maybe, contact a local HCP for a hearing test.

Improved Prescription Hearing Aids

As more and more new players enter into OTC hearing aid arena, it is probable that new and innovative technology will be introduced. Very likely, some of this technology will exceed what is available in prescription products, and we could see prescription hearing aids adopting some of these new features.

More HCPs Following Best Practice

As self-fitting OTC hearing aids become common place, it’s important for HCPs to offer services that go beyond what the patient can do themselves. Let’s take probe-microphone measures as an example, a procedure that has been part of hearing aid fitting guidelines for over 30 years, and easily could be used as part of an OTC fitting process. If an HCP, however, does not conduct these measures, what then do they have to offer to help the patient optimize the fitting?

Unbundling of Product vs. Services

It is historically common for HCPs to use a bundled approach when selling hearing aids. That is, the patient doesn’t know what they are paying for the product itself vs. the services that are provided with the product. While this has proven to work quite well, many argue that it is best for the profession if an unbundled approach is used. This then clearly points out that the patient is not simply buying a widget (which today easily can be price-shopped on the Internet), but that they also are purchasing the necessary services that will serve to make the widget work effectively. Given that many HCPs will be developing a “fee schedule” to handle the services provided to patients who have purchased their OTC hearing aids elsewhere, it’s possible that this same fee schedule would then be applied to prescription hearing aid sales.

Why Include the Sale of OTC Hearing Aids in Your Practice?

As mentioned earlier, at least in early surveys, the majority of HCPs report that they are planning to sell or service OTC products (Bailey, 2022). What are the potential benefits of this approach?

- To retain a product sale, and ultimately the patient, when he or she does not want to commit to traditional hearing aids. The OTC product can serve as a gateway to prescription products.

- For a patient that is tech savvy, wants to pay less, and believes that they do not need follow-up appointments or the services included with the standard hearing aid fitting approach.

- For patients who believe that their hearing loss is not a big enough problem for the purchase and use of traditional hearing aids. The OTC product can assist the patient hearing-aid journey sooner than typical.

- To offer a variety in product price point, for patients who have different budgets, or opinions regarding the cost of hearing care services.

- To have something for all customers that walk through the door. This might include patients with very mild hearing loss, part-time users, and those who only want to use amplification for select listening situations.

- To offer a unique product for those patients who consider the self-fitting process more desirable than the professional fitting, or prefer the unique style of some of the OTC products.

Providing Services for OTC Products

Recent surveys have shown that while only about 25% of HCPs are planning on selling OTC products, 50% or so are considering providing services for the patients who already have purchased OTC instruments, or are planning on doing so. Here is list of some possible services that could be provided:

- Pre-purchase hearing test: Many consumers will not be satisfied with the quality of the “app” hearing test, and prior to purchase, will want to have a “real” hearing test from a professional. Others likely will fail the app test, and the app will likely refer them to a hearing professional.

- Pre-purchase evaluation for candidacy: In addition to the standard audiogram, some consumers might want a professional’s opinion if they are a candidate for OTC (or any hearing aid). Speech-in-noise testing and self-assessment inventories (e.g., HHIE) would be helpful.

- Pre-purchase OTC selection guidance: Many consumers will be overwhelmed with the number of OTC hearing aids that are available, even for the same price point. HCPs offering “OTC purchase consultations” could be a welcome service.

- Orientation and training: Assist the patient with learning how to correctly insert and remove the hearing aids. Assist in operation of app and streaming features.

- Quality control: Conduct electroacoustic 2-cc coupler analysis of the hearing aids to ensure proper function.

- Prescription fitting: Conduct probe-microphone measures and adjust the hearing aids as much as possible to optimize fitting based on validated prescriptive targets.

- Benefit assessment: Conduct unaided and aided speech-in-noise testing to ensure appropriate benefit is present. Findings also can be used for counseling regarding real-world expectations.

- Assist in self-assessment of benefit and satisfaction: Using validated self-assessment inventories (e.g., IOI-HA, HHIE, APHAB) determine if patient is experiencing expected benefit and satisfaction. Results can be used for counseling regarding real-world expectations.

- Rehabilitative audiology: Provide aural rehabilitation services including auditory training options.

HCPs to the Rescue

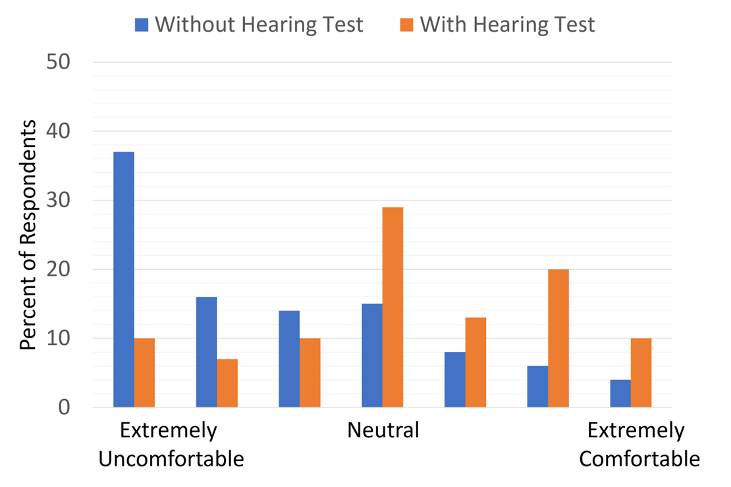

While many OTC hearing aid purchases will be from the shelves or racks in stores, there still will be a large online presence, including the outlets that have the product in their stores. In this regard, a recent study revealed some interesting findings concerning the online purchase of hearing aids (Singh & Dhar, 2023). All respondents were asked to rank the following pathways in order of preference for the purchase of hearing aids: (1) through an HCP (in-person), (2) online that requires a hearing test, or (3) online that does not require a hearing test. Eighty-four percent of respondents (874 of 1037) ranked the in-person pathway as their first choice. Further analysis showed that with every additional year of age, the odds of purchasing hearing aids online decreased by 5%.

The respondents also rated their comfort in purchasing hearing aids online, relating to whether they had a hearing test. The findings are shown in Figure 10. Note that even with a hearing test, a large percentage are uncomfortable, but without a hearing test, this increases to about 2/3 of the respondents, with nearly 40% giving the rating of “extremely uncomfortable.”

Figure 10. Individuals rating their “comfort level” for ordering hearing aids online. Results shown for whether they already have a hearing test. (adapted from Singh & Dhar, 2023).

Recall that earlier, we discussed the findings from the large Humes et al (2017) clinical study, where three groups were fitted with hearing aids: Best Practice, Consumer Decides, and a Placebo group (fitted with hearing aids with 0 dB gain). While in our previous discussion we highlighted some the results that were concerning, there were some positive outcomes from that study, which relate to the service of OTC hearing aids (Humes, 2020).

From the consumer-decides group, 50% indicated at the end of the 6-week trial that they did not want to keep their hearing aids. However, over 90% of these opted for a second 4-week follow-up trial after they were re-fitted using Best Practices. This suggests that perhaps, even when the initial self-fitting is not successful, patients won’t “give-up” on using hearing aids.

A second finding of interest was that initially 33% of those in the Placebo group (0 dB gain—presumably the “worst case” for a self-fit OTC) chose to keep their hearing aids, but when they were re-fitted employing Best Practice and had another 4-week trial, the success rate went to 92%. This points out the value of the HCP (assuming Best Practice is followed), even when the initial OTC fitting is very poor.

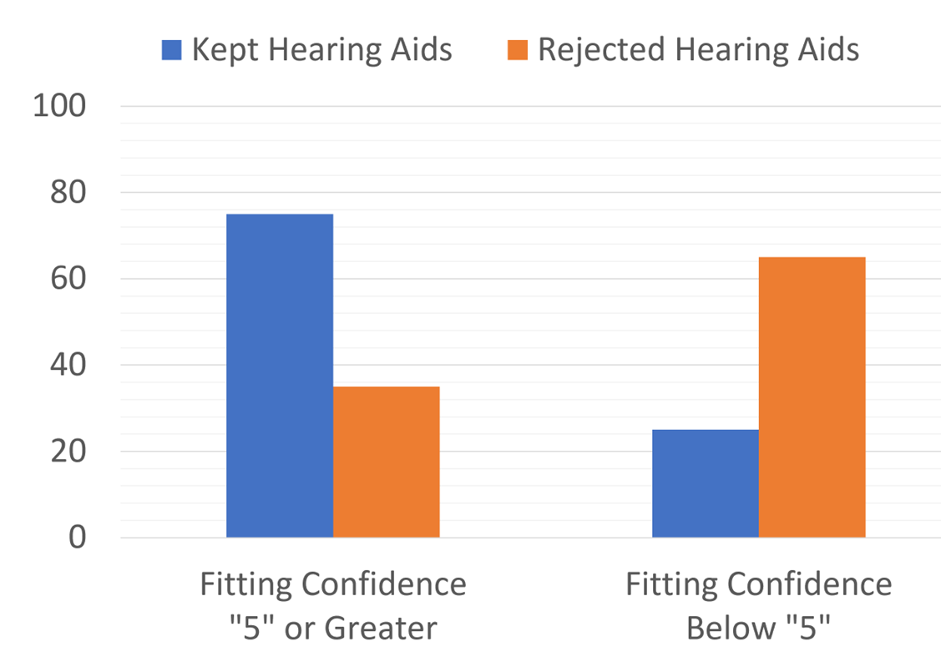

And finally, in a related study of 40 of the older adults who self-selected and fit their hearing aids using the consumer-decides approach, near the end of the trial several questions were asked regarding the self-fitting process, and the participants rated their confidence in the fitting on a 1 to 10 scale (10=Very Confident). Figure 11 (Humes, 2020) illustrates the relationship between the rating of “fitting confidence” and whether the participant chose to keep using the hearing aids. As shown, confidence in the self-fitting (a rating of “5” or greater) impacted the decision whether to keep the hearing aids—75% vs. only 25% when the participant was not confident. Likewise, 65% of those who were not confident in their fitting ability chose not to keep the hearing aids.

Figure 11. Percent of participants who kept or rejected their hearing aids based on their confidence of their own self-fitting (adapted from the data of Humes, 2020).

The bottom line: Clearly, the confidence in the fitting is important, and it’s very possible that those who purchase OTC products will want to come to the HCP to ensure that the fitting is appropriate, or to hear about alternative devices.

In Closing the Volume

The long-awaited OTC hearing aids are here, and so far, the “big splash” has been more like a trickle. There certainly are some concerns regarding the resulting “goodness” of the fittings, do consumers really know what is best for them, but perhaps this will work out okay. As we have reviewed, for those HCPs who have decided to “jump into” OTC sales and/or service, there are many options available. The value of good fittings and good service will always remain, and it is very possible the OTC wave will in fact increase the number of patients seeking both from HCPs.

References

Almufarrij, I., Dillon, H., & Munro, K. (2022). Do we need audiogram-based prescriptions? A systematic review. International Journal of Audiology. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2022.2064925

Bailey, A. (2022). OTC hearing aids—From the perspective of audiologists and hearing aid specialists. HearingTracker.com. https://www.hearingtracker.com/pro-news/what-do-audiologists-think-of-otc-hearing-aids

Boothroyd, A., & Mackersie, C. (2017). A "Goldilocks" Approach to Hearing-Aid Self-Fitting: User Interactions. American Journal of Audiology, 26(3S), 430-435.

Convery, E., Keidser, G., Hickson, L., & Meyer, C. (2019). Factors Associated With Successful Setup of a Self-Fitting Hearing Aid and the Need for Personalized Support. Ear and Hearing, 40(4), 794-804.

Cunningham, D., Williams, K., & Goldsmith, L. (2001). Effects of providing and withholding post-fitting fine-tuning adjustments on outcome measures in novice hearing aid users: A pilot study. American Journal of Audiology, 10(1), 13-23.

Dawes, P., Maharani, A., Nazroo, J., Tampubolon, G., & Pendleton, N. (2019). Evidence that hearing aids could slow cognitive decline in later life. Hearing Review, 26(1), 10-11.

Hickson, L., Meyer, C., Lovelock, K., Lampert, M., & Khan, A. (2014). Factors associated with success with hearing aids in older adults. International Journal of Audiology; Suppl 1, S18-S27.

Humes, L. E. (2020). Some considerations for audiologists as the OTC hearing aid era dawns in the U.S. Canadian Audiologist, 7(2).

Humes, L., Rogers, S., Quigley, T., Main, A., Kinney, D., & Herring, C. (2017). The Effects of Service-Delivery Model and Purchase Price on Hearing-Aid Outcomes in Older Adults: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. American Journal of Audiology, 26(1), 53-79.

Hunn, N. (2014). Hearables—the new wearables. Wearable Technologies. https://www.wearable-technologies.com/2014/04/hearables-the-new-wearables.

Keidser, G., & Alamudi, K. (2013). Real-life efficacy and reliability of training a hearing aid. Ear and Hearing, 34(5), 619-629. DOI: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31828d269a

Keidser, G., & Convery, E. (2018). Outcomes with a self-fitting hearing aid. Trends in Hearing (Jan-Dec; 22, 2331216518768958.

Kemp, D. (2022). 20Q: Hearing aids, hearables and the future of hearing technology. AudiologyOnline, Article 28290. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

Kirkwood, D. (2004). Survey finds most dispensers bullish, but not on over-the-counter devices. The Hearing Journal, 57(3), 19-30.

Mackersie, C., Boothroyd, A., & Lithgow, A. (2019). A "Goldilocks" Approach to Hearing Aid Self-Fitting: Ear-Canal Output and Speech Intelligibility Index. Ear and Hearing, 40(1), 107-115.

Mackersie, C., Boothroyd, A., & Garudadri, H. (2020). Hearing Aid Self-Adjustment: Effects of Formal Speech-Perception Test and Noise. Trends in Hearing. doi: 10.1177/2331216520930545

Mueller, H. G. (1999). Just make it audible, comfortable and loud but okay. Hearing Journal, 52(1), 10-17.

Mueller, H. G. (2020). Perspective: real ear verification of hearing aid gain and output. GMS Z Audiol (Audiol Acoust). Doc05. DOI: 10.3205/zaud000009, URN: urn:nbn:de:0183-zaud0000096

Mueller, H. G., Hornsby, B. W., & Weber, J. E. (2008). Using trainable hearing aids to examine real-world preferred gain. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 19(10), 758-773. DOI: 10.3766/jaaa.19.10.4

Mueller, H. G., & Hornsby, B. W. Y. (2014). Trainable hearing aids: the influence of previous use-gain. AudiologyOnline. Available from: https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/trainable-hearing-aids-the-influence--12764

Mueller, H. G., Ricketts, T., & Bentler, R. (2017). Speech mapping and probe microphone measures. San Diego: Plural Publishing.

Olson, C. (2022). SONY CRE-C10 OTC Detailed Hearing Aid Review. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4YpC7vHgqoI&t=902s

Olson, C. (2023a). Jabra Enhance Plus OTC Detailed Hearing Aid Review. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UXgtT60y0ww&t=695s

Olson, C. (2023b). Lexie B2 Rechargeable OTC Hearing Aid Detailed Review. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qbKhQhJPApU&t=1005s

Palmer, C. (2012). Implementing a gain learning feature. AudiologyOnline. Available from: https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/siemens-expert-series-implementing-gain-11244

Powers, T. A. (2022). 20Q: OTC hearing aids - they’ve arrived! AudiologyOnline, Article 28393. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

Pilch, S. (2023). Over-the-counter hearing aids and implications for state statutes and regulations. Audiology Today, 35(1), 59-61.

Sabin, A., Van Tasell, D., Rabinowitz, B., & Dhar, S. (2020). Validation of a Self-Fitting Method for Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids. Trends in Hearing, Jan-Dec., 24, 2331216519900589.

Sanders, J., Stoody, T., Weber, J., & Mueller, H. G. (2015). Manufacturers' NALNL2 fittings fail real-ear verification. Hearing Review, 21(3), 24.

Sharma, A. (2021). Harnessing neuroplasticity in hearing loss for clinical decision making. AudiologyOnline, Article 27826. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

Singh, J., & Dhar, S. (2023). Assessment of Consumer Attitudes Following Recent Changes in the US Hearing Health Care Market. AMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Published online January 19, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2022.4344

Swanepoel, D., Oosthuizen, I., Graham, M., & Manchiaiah, V. (2023). Comparing hearing aid outcomes in adults using over-the-counter and hearing care professional service delivery models. American Journal of Audiology, 32(2), 1-9.

Wu, Y-H. (2017, June). 20Q: EMA methodology - research findings and clinical potential. AudiologyOnline, Article 20193. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

Citation

Taylor, B. & Mueller, H. G. (2023). Research QuickTakes Volume 5: OTC hearing aids—pros, cons, and implementation strategies. AudiologyOnline, Article 28695. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com