Back in QuickTakes Volume 6 (Part 1 and Part 2), we provided a toolbox that was filled with various clinical tests that could be conducted during various stages of the fitting process. We started with pre-fitting testing and continued the journey through selection, fitting, verification, and validation methods. We’re pleased that the contents of our toolbox were appreciated, as this Volume quickly became the most read of our QuickTakes series.

The toolbox really wasn’t filled, however, so for Volume 8, we are back with Hearing Aid Fitting Toolbox v2. This will be a little different, as in many cases, we’ll be reviewing articles that deal with counseling, concepts and construct, and maybe not directly with a specific test that you will administer. If you’re the type who doesn’t like all the numbers that we typically toss out in our QuickTakes series, you’ll be pleased to see that there aren’t too many in this Volume—very little math is required!

8.1: Hearing Loss Prevalence and Hearing Aid Adoption

Periodically, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) compiles data on audiometric hearing loss, self-reported trouble hearing, and the use of hearing aids. Recently, audiologist Larry Humes (Humes, 2023) reported on the findings for the three most recent surveys (2011-12, 2015-16, and 2017-20). The data (n=8,795 with complete audiograms) were for adults ranging in age from 20 to 80-plus years. The prevalence of hearing loss, measured audiometrically and self-reported, is provided for males and females by age decade.

Self-reported Hearing Problems

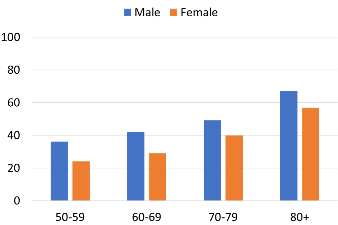

Hearing-related questions on the survey concerned “the frequency of difficulty following conversation in noise” and “how frequently hearing caused frustration when talking.” Each of these questions included responses on a 5-point scale: always, usually, at least half the time, seldom, and never. An analysis of the responses to these questions, combined with the answer to the question “Would you say that your hearing is excellent, good, that you have a little trouble, moderate trouble, a lot of trouble, or are deaf?” resulted in forming the subgroup of those respondents who have trouble hearing. A summary is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Percent of male and female respondents reporting “trouble hearing.” Data only shown for four oldest groups (adapted from Humes, 2023).

As expected from previous research, the self-report of hearing trouble increases systematically with age. The hearing problem is slightly more common for males than for females for all age groups. Overall, ~26% of males and ~20% of females, aged 20 to 80+ years, had self-reported trouble hearing.

Audiometric Hearing Loss

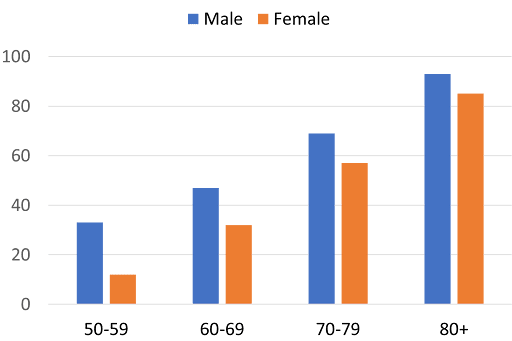

The definition of audiometric “impaired hearing” was a PTA (500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz) in the better ear =/> 20 dB. The male and female findings for the four oldest groups are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Percent of male and female respondents that had audiometric hearing loss (PTA =/> 20 dB for 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz). Data only shown for four oldest groups (adapted from Humes, 2023).

When compared to the data shown in Figure 1, in Figure 2, we see a similar male vs. female pattern, with more hearing loss for males. Also note, that for all age groups, the percent of audiometric hearing loss is greater than the percent of those reported hearing problems (See Figure 1). Overall, about 23% of adult males and 17% of adult females between the ages of 20 and 80+ years had impaired hearing.

Humes (2023) reports that there are large increases in the odds of PTA4 ≥ 20 dB HL with increasing age decade—those aged 70 to over 80 years had about 10 times higher odds of having self-reported trouble hearing relative to the 20-29 year-old group. The odds of audiometric hearing loss in these oldest age decades were at least 100 times higher than for the youngest age decade (although the effects of age and sex were smaller for self-reported trouble hearing compared to audiometric hearing loss). As expected, positive histories of noise exposure increased the odds of having trouble hearing by 50–75%. A positive history of hypertension, a positive history of diabetes, and lower education level all increased the odds of having self-reported hearing trouble by about 20–40%.

Unmet Hearing Care Needs

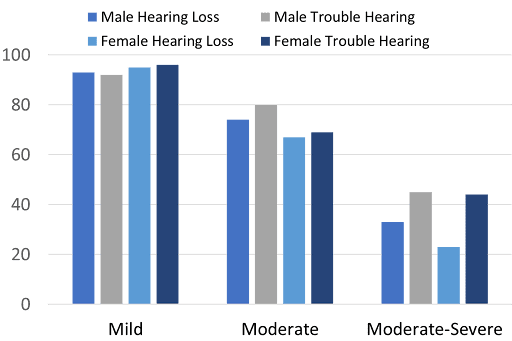

By comparing those who reported hearing trouble, and those who audiometrically had a hearing loss, to those reporting hearing aid use, Humes (2023) identified what he termed “unmet hearing care needs.” These findings are shown in Figure 3 for three hearing loss levels.

Figure 3. Percent of “unmet hearing care needs” determined by those who are using hearing aids and the overall report of hearing trouble or the presence of an audiometric PTA =/> 20 dB. Results shown for both males and females for three different severity groups (adapted from Humes, 2023).

As expected, as both the measured hearing loss and the reported hearing problems became greater, the unmet hearing care needs are reduced, but are still 60-80 percent for the moderate category. In general, the results are similar for those with measured hearing loss vs. those with reported hearing trouble, except for the moderate-severe category, where those with measured hearing loss tend to be more likely to use hearing aids (i.e., fewer unmet needs).

Humes used these data for project the estimated numbers of adults with unmet hearing care needs based on a total population estimate of 234.2 million adults in the U.S. in the age range 20 to 80+ years. This was based on the audiogram, or the trouble hearing data for the respondents reporting never using hearing aids. The lowest number of adults with unmet needs was found for the audiometric definition of needs: about 21 million males and 17 million females. For unmet hearing care needs based on the respondents report of trouble hearing, it’s projected that in the U.S. there are about 23 million males and 19 million females.

The bottom line, based on Humes (2023) analysis of the NHANES data, is that there remains an incredible amount of unmet need: a high percentage of individuals, especially those with mild and moderate hearing loss might benefit from intervention from a hearing care professional. Although this finding is unsurprising (many other studies over the past several decades yield similar results), it reminds us there is a large pool of individuals who can use our help. Lastly, given the immense unmet need of those with mild and moderate hearing loss, as illustrated in Figure 3, new devices like hearing aids sold over-the-counter, and new service delivery models using teleaudiology might be effective ways to move the needle.

Time Course: Candidacy to Hearing Aid Adoption

We’ve just reviewed data discussing the number of individuals who are candidates for hearing aids but are not using them. An important concern related to this, is the delay from the time that a person is identified as a candidate to the time that they adopt hearing aids. Various numbers have been tossed out over the years, but one of the most comprehensive studies on this topic was published by Simpson et al. (2019). These authors defined hearing aids candidacy as an SRT ≥30 dB HL in at least one ear, or thresholds at 3000 and 4000 Hz ≥40 dB HL in either ear. This resulted in a total sample of 732, with two comparison groups of hearing aid candidates: those who never adopted hearing aids (n = 514) and those who adopted hearing aids while they were in the study (n = 218). Individuals who adopted hearing aids during the study were classified as “successful” or “unsuccessful” users, based on self-report.

Demographic information was collected for: age, chronic health, race, retired, education, socioeconomic status, and marital status. In addition to the pure-tone audiometry and SRT conducted to determine candidacy, participants received monosyllabic word testing in quiet (NU-6), speech-in-noise testing (SPIN) and also completed the HHIE/A.

The unadjusted estimation of time from hearing aid candidacy to adoption for the full participant cohort (N = 732) was 8.9 years. In stratified analysis of time to hearing aid adoption the following was observed:

- A trend toward earlier adoption as age categories increased, with individuals aged 65 or younger averaging 9.2 years to adoption and those older than 76 years averaging 6.6 years to adoption.

- Females averaged 8.7 years to adoption compared with 9.0 years for males.

- Individuals in the low socioeconomic status (SES) category averaged 10.7 years to adoption compared with 8.7 years in the middle and 8.3 years in the high SES categories.

- Statistical significance for race was observed. Non-white participants took an average of 15.2 years to adopt hearing aids compared with 8.6 years for white participants.

Regarding the audiologic measures:

- As low-frequency PTA increased from ≤10 dB HL to >30 dB HL, the average time to hearing aid adoption decreased from 11.2 to 4.3 years.

- For the high-frequency PTA, when the average was ≤45 dB HL, the estimated time to hearing aid adoption was 11.5 years, however, for those with PTAs >65 dB HL, estimated time to adoption was 5.9 years.

- For the HHIE/A, relatively small differences in scores had a surprisingly significant effect on adoption time; the 25-item version was used, and scores therefore could vary between 0 (best) and 100 (worse). When scores were =/< 10, estimated adoption time was 11.1 years. When HHIE/A scores were >16, adoption time dropped to 4.3 years.

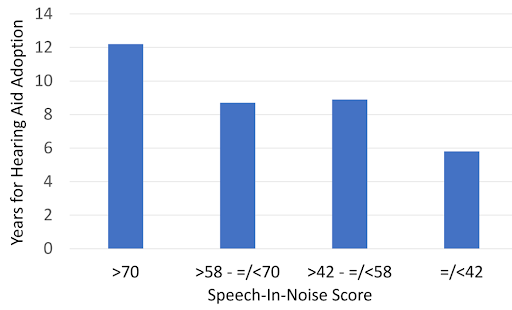

- Speech-in-noise testing revealed what might be predicted, that those participants with poorer word recognition had less time in adopting hearing aid use. Adoption time went from 12.2 years for those with scores over 70%, down to 5.8 years for those with score =/<42% (See Figure 4).

Figure 4. Shown is the relationship between the time for adoption of hearing aid use and the participants’ speech-in-noise score. The scores shown are for the keyword recognition for the low-context sentences of the Speech In Noise Test (SPIN). The SPIN sentences were presented at 50 dB SL relative to the participant’s calculated babble threshold, with babble presented at a +8 dB signal-to-noise ratio. (Adapted from Simpson et al., 2019).

Most of the data from this work by Simpson et al. (2019) agrees with previous studies of this type; their overall finding of 8.9 years is consistent with thoughts from past decades. While we of course would like the adoption rate to be 0 years, their findings do point out nicely what factors to consider with new patients who are “on-the-fence.” In particular, the predictability gleaned from the speech-in-noise testing and the HHIE/A cannot be ignored. Could it be that simply the act of taking these tests, doing poorly, and then counseled about the results, speed up the adoption process? We think it is quite possible.

MarkeTrak Data: Factors Impacting Hearing Aid Adoption

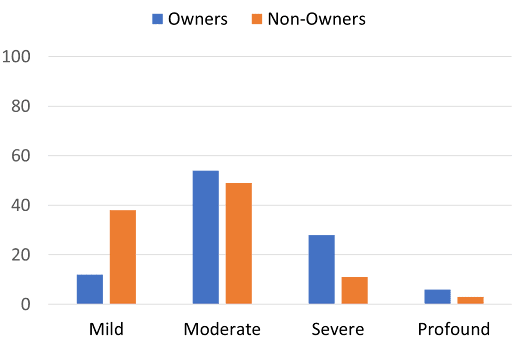

As we’ve just discussed, there are many factors that impact the adoption of hearing aids, and often, this topic is part of the MarkeTrak surveys. Such was the case for MarkeTrak10, and a summary of some of these data were provided in an article by Jorgensen and Novak (2020). For much of the findings, the group was divided between hearing aid owners and non-owners. As expected, the non-owners did not report as much hearing loss as the owners, but the difference was not as great as one might think (See Figure 5). Indeed, considerably fewer of the owners stated that their hearing loss was “mild,” but for those reporting moderate hearing loss, there was little difference between owners vs. non-owners (i.e., 54% vs. 49%)—if we include the severe and profound categories, 63% of the non-owners state that their hearing loss is moderate or greater.

Figure 5. Percent of owners vs. non-owners who report hearing loss for four different hearing loss categories (adapted from Jorgensen & Novak, 2020).

By comparing owners to non-owners, it was estimated that 42% of those over the age of 65 with self-reported hearing problems own hearing aids. This adoption rate drops to 23% for the 35-64 years group, and 30% for the younger than 35 group. Yes, you read that correctly, the younger group had a higher adoption rate than the middle-aged respondents, a finding that also was present in MarkeTrak2022, and something that we have discussed in a previous QuickTakes article (Volume 7; Taylor & Mueller, 2024). Data from the MarkeTrak10 survey projected that in the U.S., there are approximately 11 million nonadopters with moderate-to-severe hearing loss. This value is only about ½ of the projection we referred to earlier from Humes (2023) but recall that he included those with mild and moderate losses.

The MarkeTrak10 findings suggested that the time course for obtaining hearing aids is somewhat faster than found by Simpson et al. (2019). Recall that Simpson et al. (2019) reported 9.2 years for individuals aged 65 or younger, and 6.6 years for those older than 76. The MarkeTrak10 survey (median age of hearing aid owners was 71 years) found that from the time that the individual first noticed a hearing problem to the time that they were tested was 4.2 years, and that the first set of hearing aids was purchased at 6.2 years. In other words, after seeing an HCP (testing), on average, hearing aids were purchased within 2 years. These data of course are based on the person’s memory (unlike the Simpson et al. data), and it’s also possible that the respondent didn’t want to admit how long they really waited to obtain amplification.

Some MakeTrak10 findings which impacted adoption (Jorgensen & Novak, 2020):

- Men are more likely to have self-perceived hearing loss—12.8 of total sample vs. 8.9% for women. The rate of hearing aid adoption was 34% for both groups.

- For many general questions regarding hearing difficulty, the responses from owners vs. non-owners was quite similar. Two questions where the problems were considerably higher for the owners was: “I have trouble understanding things on TV,” and “I have trouble understanding the speaker in a large room.”

- Both ENT and general physicians recommended only 12% of people self-identified as having hearing problems consider pursuing hearing aids. In contrast, those who reported that the first person they sought information from was an HCP, 52% had confirmed hearing loss, and 41% reported that hearing aids were recommended.

- When asked why they made the appointment to seek help with their hearing, 52% of hearing aid owners stated it was because of a recommendation from a friend, whereas only 27% of non-owners gave this reason. On the other hand, 53% of non-owners stated it was because of the recommendation of a spouse/partner; only 25% of owners gave this reason.

In Summary

In this first section of Volume 8, we have provided some background regarding the prevalence, and the projected “unmet hearing care needs.” Research shows that even for those who recognize that they have a hearing loss, adoption of hearing aid use is often postponed, or simply doesn’t occur. As shown in the MarkeTrak10 survey, many non-owners report having a hearing loss, and have had their hearing tested by an HCP. In the following sections of this QuickTakes Volume, we’ll discuss tools some that can be used to further evaluate these individuals, and hopefully move them into the hearing aid owner category.

8.2: Theories and Models Related to the Patient Journey

In the previous section we discussed the unmet need for hearing health care in the U.S. If we include those individuals with a mild impairment, it is estimated that the total is 39-42 million (Humes, 2023). Interestingly, MarkeTrak data tells us that a large percent of these individuals with unmet needs—people who state they have a hearing loss but do not use hearing aids—have been evaluated by a hearing care professional (HCP). We can assume, that in most cases, the use of hearing aids was recommended at the time of this visit, but for one reason or another, the patient didn’t follow through with the recommendation. Why is this? If we look carefully at the “why,” it might be possible to speed up the journey to hearing aid use.

Stages of Change Models

Stages of change models are common in various areas of psychology, counseling, and health care, dealing with such issues as smoking, alcohol abuse, addiction, weight control, etc. The stages of change model that most of us are most familiar with is the Kübler-Ross Stages of Grief, born from her book On death and dying (1969). As a refresher, the stages are: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. While this model is geared toward grief, often associated with dying, there are stages of change theories and models that can be adapted for hearing health care.

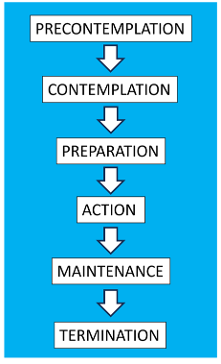

Transtheoretical Stages of Change Model

This is perhaps the most common model used relating to health behavior, going back at least 40 years to the 1980s work of Prochaska & DiClemente (1983). The Transtheoretical Model (TTM; also called the Stages of Change Model), evolved through studies examining the experiences of smokers who quit on their own, compared to those requiring further treatment. TTM focuses on the decision-making of the individual and is a model of intentional change. It operates on the assumption that people do not change behaviors quickly and decisively.

As mentioned, much of the research related to this model has centered around smoking cessation and other addictive behaviors such as alcohol and drug abuse. However, in more recent years, it has been used for numerous other applications ranging from stress management, medication compliance, exercise participation, weight control, and even preventative measures, such as medical screening tests. Given the long time-course to treatment and low hearing aid uptake rate, the TTM seems like a reasonable way to better understand how individuals cope with their condition. The model traditionally has six stages, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The six stages of the Transtheoretical Stages of Change model (from Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983).

The mostly-standardized version of this model, particularly when the model is used in conjunction with drug and alcohol addiction, sometimes has a stage referred to as “relapse.” And one stage that you see in Figure 6, labeled “termination,” is rather misleading when applied to hearing aid adoption. Even when the outcome is a successful hearing aid user, counseling and often re-programming is needed for the life of the hearing aids, and hence, the patient remains in maintenance and never really is terminated. Hence, we’ll simply focus on the first five stages shown in Figure 6. According to the TTM, a person likely to engage in health behavior change displays low Precontemplation and high Contemplation, Preparation, Action, and Maintenance scores. The following research reviews these primary five stages (see Raihan & Cogburn, 2023).

Precontemplation. These usually are people who don’t believe that they have a problem and, therefore, are very unmotivated to take action. They often lack insight regarding the consequences of their negative behavior. After all, if you don’t believe you have a problem, why would you seek help from a professional? These individuals often obsess about the negative side of change rather than recognizing the benefits that they would gain. They may exhibit elements of change (if pressure exists to do so) but will quickly return to their old habits.

Relating to hearing aid adoption. Unfortunately, this category is a large percentage of those with unmet needs. These people might be aware that they have a hearing problem, but usually are in denial, or lack awareness that hearing loss is affecting their communication ability. Individuals in the contemplation stage of change often say things during an appointment like, “Other people mumble.” Or “I hear what I need to hear.” They are quick to point out the negatives (true or not) of using hearing aids. If they do come in for a hearing test, it’s often because a family member made the appointment. If pressured enough, they will try hearing aids, with probably no intent of ever using them.

Contemplation. At this stage, the patient is aware they have a problem and understand it might also be a problem for others. But, they may not be sure that the problem is worthy of correcting. They are still hesitant to make a commitment to taking the necessary steps toward change. People can be stuck in contemplation for several months, or even years. In general, however, they might be open to receiving some generic information about the problem.

Relating to hearing aid adoption. Persons in the contemplation stage might start to admit to close friends and family members that the reason they are missing parts of conversations is because of their hearing loss. However, many contemplators are more than happy to put the onus on others. For example, it is common for some contemplators to say they don’t have a hearing problem when their spouse talks louder or when the TV volume is turned louder. They may even start to take some limited action to assist with their hearing, such as positioning themselves better for conversations, asking people to repeat when they miss something, using captioning while watching TV, etc. They are uncertain, however, if any treatment (obtaining hearing aids) is needed.

Preparation. It is during this stage the person acknowledges that a behavior is problematic and is more or less ready to make a commitment to solve the problem, recognizing that receiving treatment is probably better than the status quo. People begin gathering information during this stage, which should be encouraged. People usually intend to act in the next month or so, and usually have taken behavioral steps towards that direction over the past year.

Relating to hearing aid adoption: The person becomes more “tuned-in” to hearing aids and hearing aid use; paying more attention to television ads and conducting Google searches. People also start having conversations with friends and colleagues who are using hearing aids or have tried hearing aids. It is relatively easy to recognize someone who is in the preparation stage because they ask a lot of questions about hearing tests and hearing aids. In some cases, however, the information gathering can be excessive, including sorting out and categorizing brands, features, and prices.

Action. As the term suggests, in this stage meaningful change happens. People gain confidence in their decision and are willing to receive assistance and support. As the name of the stage implies, people in the action stage readily follow the recommendations and guidance of the hearing care professional. Importantly, in this stage, change is not only the action, itself, but all the prerequisite work required to act on changing the behavior. Prematurely jumping to this stage, without adequately preparing can lead to difficulty.

Relating to hearing aid adoption. Persons with hearing loss often need time to process or grasp the consequences of their condition before they take action. For some it might be just a few months, for others it might be several years. Hence, hearing care professionals are advised to respect the time it takes the individual to move into the action stage of change. In reality, many patients who are in the clinic for the first time having their hearing tested are probably not yet in the action stage of change. Laplante-Levesque et al. (2015) evaluated 224 adults who had failed an online hearing screening and determined that less than 5% of this group were in the action stage of change. Although it is likely that a higher percentage of individuals who are in the clinic seeking help from an HCP are in the action stage, these research findings suggest us that most first-time help seekers are probably not in the action stage. This represents an opportunity to guide these individuals into action by applying some specific counseling strategies that speed the journey. The simple act, for example, of asking a patient in one of the “pre-action” stages of change to describe the potential benefits of wearing hearing aids is one counseling strategy that could move some patients closer to the action stage of change. For more examples of counseling strategies that might guide patients into the action stage, see Taylor (2022).

Maintenance. As people progress through this stage, they become more confident that obtaining the treatment was a wise decision. They are less fearful that they will return to their old behavior. They have a new status quo.

Relating to hearing aid adoption. Following the initial fitting, the patient returns within a few weeks for follow-up counseling. Programming changes are made if necessary as well as re-instruction of patient-controlled features. The patient completes a self-assessment inventory to assess if fitting goals have been met. Future return visits are scheduled periodically, and communication is maintained through tele-audiology.

Recently, Bennett and colleagues (2024) created a specific counseling program that we think fits well into the maintenance stage of change. Their approach goes by the acronym AIMER. The AIMER counseling approach is a structured framework designed to enhance the counseling process by focusing on the emotional and social needs of the individual. Although the AIMER approach can be applied to any facet of the patient’s journey, we think it is particularly well-suited to be used during post-fitting follow-up visits. AIMER stands for Assessment, Intervention, Monitoring, Evaluation, and Review. Each component plays a critical role in ensuring effective outcomes. Here's a quick breakdown of each element:

- Assessment: This initial phase involves gathering comprehensive information about the patient’s background, current situation, and presenting issues. The aim is to develop a thorough understanding of the patient’s needs, strengths, and challenges.

- Intervention: Based on the assessment, specific interventions are designed and implemented. These interventions are tailored to address the patient’s unique needs and may include various therapeutic techniques and strategies.

- Monitoring: Continuous monitoring of the client's progress is crucial. This involves tracking changes, both positive and negative, to ensure that the interventions are effective and to make adjustments as needed.

- Evaluation: Periodic evaluation is conducted to assess the effectiveness of the counseling interventions. This involves reviewing the patient’s progress towards their goals and determining the overall impact of the therapy.

- Review: The final phase involves a comprehensive review of the entire counseling process. This includes reflecting on what worked well, what didn't, and any lessons learned. The review phase helps in refining future counseling strategies and ensuring continuous improvement.

The AIMER approach, which we will revisit later in Section 8.5, underscores that the maintenance stage of change is a dynamic process. Using AIMER ensures that the HCP’s counseling is responsive to the patient’s evolving emotional and social needs and that outcomes are continuously optimized.

More Research on the TTM

There has been some interesting research regarding how fast people move from one stage to another (Prochaska et al., 1992). Findings revealed that moving from one stage to the next within one month will double one's chances of acting on changing behavior in the next six months. If someone is still in the precontemplation stage at the of first month (and nearly all hearing candidates still are), only 3% progress to action by six months. For contemplators remaining in this stage for one month, only 20% acted by six months. This helps explain the slow adoption rate of hearing aid use that we’ve discussed.

Earlier we mentioned that we would just use the five basic stage categories, shown in Figure 6. We should mention, however, that with hearing aid use, “relapse” is more common than we would like—something that has historically been referred to as an “in-the-drawer” fitting. While we don’t usually refer to it as relapse, this is when the patient purchased the hearing aids, did not return them, but now is not using them. Dillon et al.. (2020), for example, conducted an extensive survey of hearing aid owners in the UK and determined that 20% of the respondents did not use their hearing aids at all, and another 30% of respondents reported that they used them sporadically. Hearing aid manufacturer data from the US and Europe show similar trends with 20 to 40% of hearing aid owners reporting that they use their hearing aids four hours/day or less (EHIMA, 2018-2022).

Closer to home in the US, where direct-to-consumer (DTC) products have been available for several decades, these “non-use” numbers are harder to track. Some estimate that of those who make the decision to purchase hearing aids, 10-20% do not use them. This, of course, would seem predictable with DTC products, but even HCPs following best practice will admit that they have some patients who, they might discover months or even years later, stopped using their hearing aids. Oftentimes, these are not the patients who are coming back and complaining about one thing or another, as they are somewhat reluctant to admit that they didn’t follow through with the treatment plan. Our best guess is that these are patients who skipped the planning stage, and maybe even the contemplation stage, and went directly to action—perhaps because of pressure from family members. Longitudinal studies with smoking and drug addiction have shown what might be expected . . . the longer the person stays in the maintenance stage, the less likely there will be relapse. The same is true for hearing aid use—it’s uncommon for someone who has been a regular user for over six months, or certainly a year, to abandon hearing aid use.

Health Belief Model (HBM)

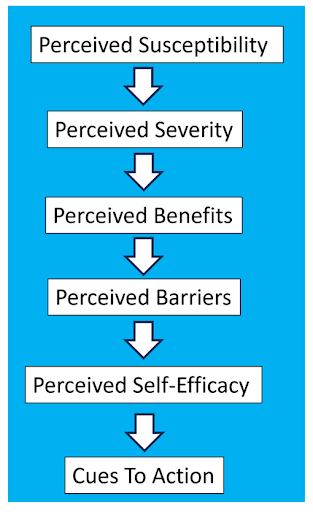

The HBM is one of the oldest models and has been applied to a very broad range of health behaviors and populations. The model is based on six constructs that influence the likelihood that people will take action to prevent, screen for, or control health conditions (See Figure 7; Rosenstock, 1974). The general premise of the model is that people are more inclined to change behavior when they believe that doing so might reduce a threat that is probable, and that would have severe consequences if it occurred.

Figure 7. The six stages of the Health Belief Model.

Saunders et al. (2016) nicely review the six constructs of the HBM, and the following is taken from their work:

- Perceived susceptibility: The feeling of being vulnerable to a condition and the belief of being at risk of acquiring the condition.

- Perceived severity: Belief in the seriousness of the health and social consequences incurred if affected by the condition.

- Perceived benefits: Belief that an intervention will result in positive benefits.

- Perceived barriers: Barriers believed to be needed to be overcome to effectively conduct an intervention.

- Perceived self-efficacy: Belief in one’s ability to use and gain benefit from an intervention.

- Cues to action: Prompts to take action, which could be internal, such as symptoms of a health problem, or external such as communication from healthcare providers, other people, or media.

According to the HBM, a person likely to engage in behavior change perceives high severity, susceptibility, benefits, cues for action and self-efficacy, and has few barriers.

The impact on these stages on heath behavior have been studied extensively. Going back to 1984, Janz and Becker, using a “significance ratio” across 46 studies found that the barriers component had the most consistent relationship (89%), followed by the susceptibility (81%), benefits (78%) and severity (65%) components. Carpenter (2010), using a meta-analysis approach, examined the strength of the correlations. The barriers component was found to have the highest average correlation (r = −0.30), followed by benefits (r = 0.27), severity (r = 0.15) and susceptibility (r = 0.05). In general, studies of this type have found significant, but small correlations between the HBM and health behavior.

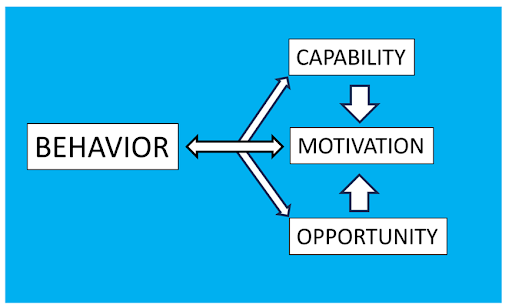

COM-B Behavior Model

A third model that has sometimes been used relative to hearing aid adoption is the COM-B (Michie et al., 2011). The name is an acronym for the three primary components for change: Capability + Opportunity + Motivation can change Behavior (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. The components of the COM-B behavior model (adapted from Michie et al., 2011).

The steps can be described as follows:

- Capability. Refers to an individual’s psychological and physical ability to make a change, or to participate in an activity. Relating to a delay in hearing aid adoption, this could be related denial or minimizing hearing problems, a perceived stigma regarding the use of hearing aids, or the belief that hearing aids are not helpful.

- Opportunity. Refers to external factors that make a behavior possible. Factors could be things like social environments, an improved financial situation, or effective marketing regarding the cost of hearing aids.

- Motivation. The conscious and unconscious cognitive processes that direct and inspire behavior. Often, the decision to obtain hearing aids is related to positive reports from friends and family who are hearing aid users, or a significant event where the hearing loss caused more problems than usual.

This model recognizes that behavior is influenced by many factors, and that behavior changes are induced by modifying at least one of these components. Barker et al. (2016) examined, by interviewing dispensing audiologists, whether the application of the COM-B method could be used to help understand the individuals with hearing loss who choose not to use hearing aids. The respondents believed that physical capability was not an issue, but both physical and social opportunity were important. And, as we all know, they also agreed that motivation played an important role.

Health Behavior Scales and Hearing Aid Adoption

Various research studies have examined how these health behavior scales could be used to assist in the speeding of the adoption of hearing aids, for those individuals who recognize that they have a hearing problem. One study of this type was by Saunders et al. (2016), who administered several self-assessment scales to a large group of adults (n=167; mean age 69.3 years) seeking hearing help for the first time. At the six-month follow-up date, 120 (72%) had taken up hearing aids, and 47 (28%) had not. Importantly, these were individuals seen at a VA clinic, and hence, the cost of hearing care was not an issue.

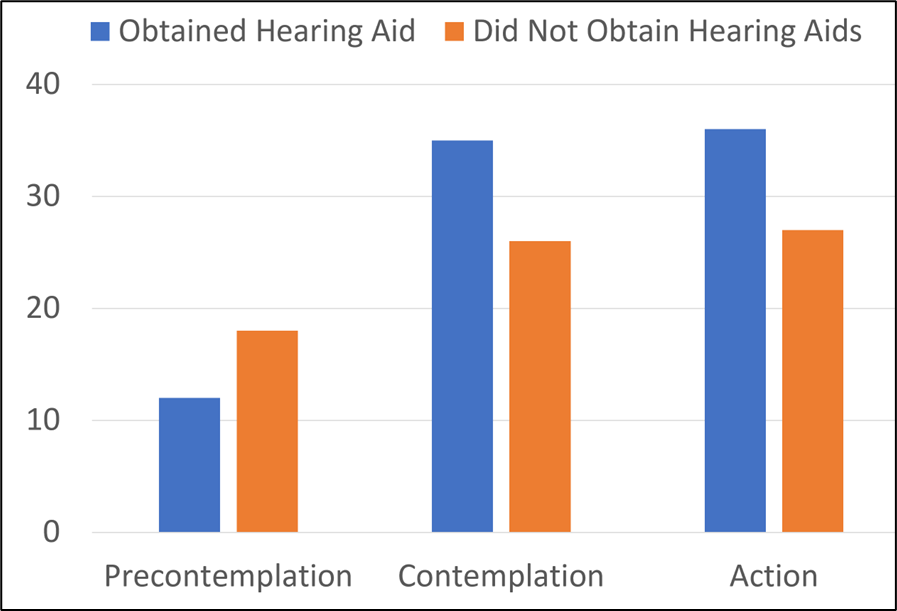

One of the self-assessment scales given to all participants was the University of Rhode Island change assessment (URICA). For this study, original items of the URICA were adapted for hearing health behaviors. The adapted URICA consists of 24 items that assess readiness for change on three eight-item scales: precontemplation, contemplation, and action—note that these are three of the stages we discussed earlier taken from the TTM (see Figure 6). A higher URICA score indicates greater agreement with the TTM construct being assessed.

Figure 9. Shown is the relationship between the health behavior stage and the decision to obtain hearing aids. The Y-axis is the score for the modified University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA) scale.

One of the findings from the Saunders et al. (2016) study is shown in Figure 9. The Y-axis is the URICA score. Note the expected findings—for those who obtained hearing aids, the URICA score was lower for Precontemplation, and higher for both Contemplation, and of course, Action. Saunders et al. also examined hearing aid uptake relative to the stages of the HBM (see Figure 7). Those participants who obtained hearing aids had higher HBM scores for Susceptibility, Severity and Benefits.

Regarding the use of the constructs of the TTM and HBM for understanding hearing health behaviors, Saunders et al. (2016) summarized that attitudes and beliefs:

- Were associated with future hearing health behaviors.

- Were effective at modeling later health behaviors.

- Change positively following behavior change.

- Are better predictors of hearing-aid outcomes than are attitudes and beliefs at the time of initial hearing help seeking.

Based on their findings, the authors conclude that a counseling-based intervention, targeting the attitudes preventing behavioral change has the potential to increase uptake of hearing health care.

As mentioned earlier, there have been several studies relating health behavior change models to audiology and the use of hearing aids. The most common perhaps has been the TTM “stages of change” which looks at the process of intentional change in behavior (see Figure 6). Manchaiah et al. (2018) conducted a descriptive literature review aimed at identifying and presenting a summary of research (n=13 studies) that used TTM to study the attitudes and behaviors of adults with hearing loss.

In general, the researchers’ conclusions were:

- There are positive associations between stages of change and help-seeking, intervention uptake, and hearing rehabilitation outcome, such as benefit and satisfaction.

- Associations with intervention decisions and intervention use were not evident.

- Understanding the readiness toward help-seeking and uptake of intervention in people with hearing loss based on TTM may help clinicians develop more focused management strategies.

Summary

The time delay for people to obtain hearing aids, following their acknowledgement that they have a hearing problem, seems to have always been a major concern for both HCPs and manufacturers. This large, underserved population in fact, has been the enticing data that has encouraged the emergence of many start-up hearing aid companies—most of which have failed. As HCPs, we are always looking for new ways to speed up the process. As we have reviewed here, taking various health behavior change models that have been successful in other health areas, and applying them to hearing aid adoption, may help in understanding the patients current thinking, and steer patient counseling in the best direction.

8.3: Before the Fitting - Understanding Patients’ Emotional and Psychosocial Concerns

As we discussed in the previous section, the journey to obtain hearing aids usually starts in the precontemplation and contemplation stages. At this point, the patients are aware that they have a hearing loss and acknowledge that this might be a problem not only for them, but for family members. Often associated with this, however, is emotional distress, which can be overlooked by the HCP, who is anxious to provide technical assistance. Research has shown that considering an individual’s experiences of living with the hearing loss disability, and the potential emotional consequences of this handicap, often will improve overall patient care. In this section, we’ll discuss how an understanding of this will assist in our patient counseling, and hopefully facilitate treatment.

Emotional Distress Associated with Hearing Loss

Psychological and emotional distress can negatively affect help-seeking for hearing loss treatment and the use of hearing aids. Bennett et al. (2022) examined the social challenges and emotional distress in relation to hearing loss and the coping mechanisms employed. Their data was collected in focus groups for 21 adults who had hearing loss and reported emotional distress due to the hearing handicap.

Their findings revealed that individuals described their social and emotional experiences of hearing loss in terms of:

- Negative consequences (social overwhelm, fatigue, loss, exclusion)

- Identity impact (how they perceive themselves and are perceived by others).

- Emotional distress (frustration, grief, anxiety, loneliness, and feeling burdensome).

Coping strategies that were reported included: avoidance, controlling the listening environment, humor, acceptance, and assertiveness. The authors report that many participants described a lack of effective coping strategies and tended to rely on avoidance of social interaction. This of course leads to increased social isolation, which we know has been associated with cognitive decline. Bennett et al. (2022) conclude by pointing out that despite the recognized need of our patients, HCPs do not have a formalized method to intervene and assist with the social and emotional difficulties that occur due to hearing loss.

Patient Interaction and Communication

We know that effective communication with our patients throughout the hearing aid fitting process positively influences adherence to treatment, patient outcomes and satisfaction, and is a vital component of patient-centered care. This has not been commonly studied, however, in the area of audiology, in particular the hearing aid fitting process. One study that did systematically examine this area was the research of Grenness et al. (2015), who explored the verbal communication between audiologists and patients/companions throughout diagnosis and management planning in initial audiology consultations. Their goal was to describe the communication in these interactions by examining the number, proportion, and type of verbal utterances by all speakers (audiologist, patient, and companion when present).

They collected data from a total of 62 audiological rehabilitation consultations involving 26 different audiologists. All patients were older than 55 years, and a companion was present for 17 of the consultations. The encounters were filmed and analyzed using the Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS). If you’re not familiar with the RIAS, this is a form of conversation analysis that was first introduced in 1977 (see review by Roter & Larson, 2002), used mostly for coding dialogue, and has been widely used in the U.S. and Europe for many different disciplines. It’s reported that its popularity is because of the system's ability to provide reasonable depth, sensitivity, and breadth while maintaining practicality, functional specificity, flexibility, reliability, and predictive validity to a variety of both patient and provider outcomes. The RIAS is applied to the smallest unit of spoken expression to which a meaningful code can be assigned, generally a complete thought, expressed by each speaker throughout the medical dialogue.

One of the RIAS findings relates to communication profiles, which examines mean total utterances, range, and proportion of utterances for each of the four RIAS categories. The four categories for the caregiver (audiologists in this study) are: Education and counseling, Data gathering, Building a relationship, and Facilitation of patient activation. The four categories for the patient are: Information giving, Question asking, Building a relationship, and Activation and engagement.

Data reported by Grenness et al. (2015) for the audiologist for the utterances throughout the diagnosis and management planning phase:

- Education and counseling in nature was 48%. An estimated 83% of the education and counseling was biomedical in content (e.g., “this type of hearing loss is permanent and most likely the result of aging”).

- An estimated 71% of the information given was affect-neutral (e.g., “there are two main styles of hearing aids”). An estimated 29% of the information was persuasive in nature (e.g., “You’ll notice a big difference in this hearing aid because of the speech enhancement; it’s worth the extra cost”).

- The second most common category of utterances for audiologists was building a relationship (26%).

- Audiologists spent 22% of their utterances on facilitation and patient activation, consisting mostly of procedural utterances such as transitions and orientations.

- The smallest category of utterances for audiologists was data gathering (4%); closed-ended psychosocial/lifestyle questions were most frequent.

Grenness et al. (2015) report the following summary of patient utterances during the diagnosis and management planning phase:

- Most common was building a relationship (60%); agreement utterances were the most common, followed by social talk and emotional talk.

- Patients spent 25% of their utterances giving information; slightly more than half of this information was psychosocial/lifestyle in nature.

- Activation and engagement (11%), and question asking (6%) were the least common categories of codes.

Grenness et al. (2015) summarize their findings by saying that when they interpret their results, they find that they seldom observe the desired patient-centered communication. Patients’ psychosocial concerns were rarely addressed, and patients/companions showed little involvement in the management planning process. Audiologists’ utterances categorized as education had little content explaining diagnoses or discussion of rehabilitative options (other than the use of hearing aids), and rarely engage in affective conversation. Previous research suggests that this possibly is a way of avoiding challenging emotional conversations (see Manchaiah et al., 2019 for a review). Addressing psychosocial concerns and facilitating patient engagement differentiates patient-centered from practitioner-centered consultations. These data suggest that there is considerable room for improvement among audiologists in this area.

A companion study on this general topic was conducted by Ekberg et al. (2014), which conducted systematic research exploring how patients’ concerns about hearing aids are addressed by audiologists during the clinic visit. A total of 63 consultations with 26 different audiologists (62% women) were filmed. All appointments reflected the initial hearing assessment with an adult patient (>55 years old) involving a discussion about hearing rehabilitation options; or it was a follow-up appointment in cases where rehabilitation options were not discussed during the first appointment. Companions were present in 17 of the 63 consultations. The video data were transcribed, and the transcripts included details of pauses, overlapping talk, cutoffs, intonational contours, and nonverbal communication, all found to be useful for how participants understand conversation.

Some key findings of the conversation analysis were:

- Patients raised concern about the use of hearing aids in 51% of the appointments where hearing aids were recommended.

- When patients expressed concerns regarding hearing aids, these concerns usually were psychosocial in nature.

- Typically, the concerns were expressed in a way that carried a negative emotional stance.

- Audiologists’ responses usually did not align with the psychosocial

- nature of the patient’s concern.

- Patients then, tended to escalate their concerns in subsequent speaking turns.

- Perhaps most importantly, when patients’ concerns remained unaddressed, they often left the appointment without making a decision about using hearing aids.

We know from the work of Erdman (2013) and others, that audiologists must be prepared to listen, empathize, and validate patients’ experiences and feelings about their hearing loss and possible related treatment. Ekberg et al. (2015) state that the findings from their study suggest that there appears to be a need for further development in this area within audiologic practice. There may be some hope, however, as Kris English and colleagues (1999) reported that a significant change was identified in the number of affective responses made by audiologists in their patient conversations after they had completed a counseling course.

To continue our discussion on this topic, we’ll also mention the work of Grenness et al. (2014a), who specifically studied audiologic rehabilitation from the perspective of older adults who had owned hearing aids for at least one year. Their data analysis revealed three dimensions: the therapeutic relationship, the players (audiologist and patient), and the clinical processes. They point out the critical need for a therapeutic relationship, a fundamental requirement for healthcare interactions. According to participants in this study, the key ingredient in developing a therapeutic relationship was trust. Descriptions of audiologist behaviors consistent with a trustworthy professional were interpersonal skills such as: caring, listening, friendliness, and providing ample time for the patient to respond to the audiologist’s open-ended questions. The authors point out that trust is particularly important in the context of audiologic rehabilitation due to the sale of hearing aids in many settings.

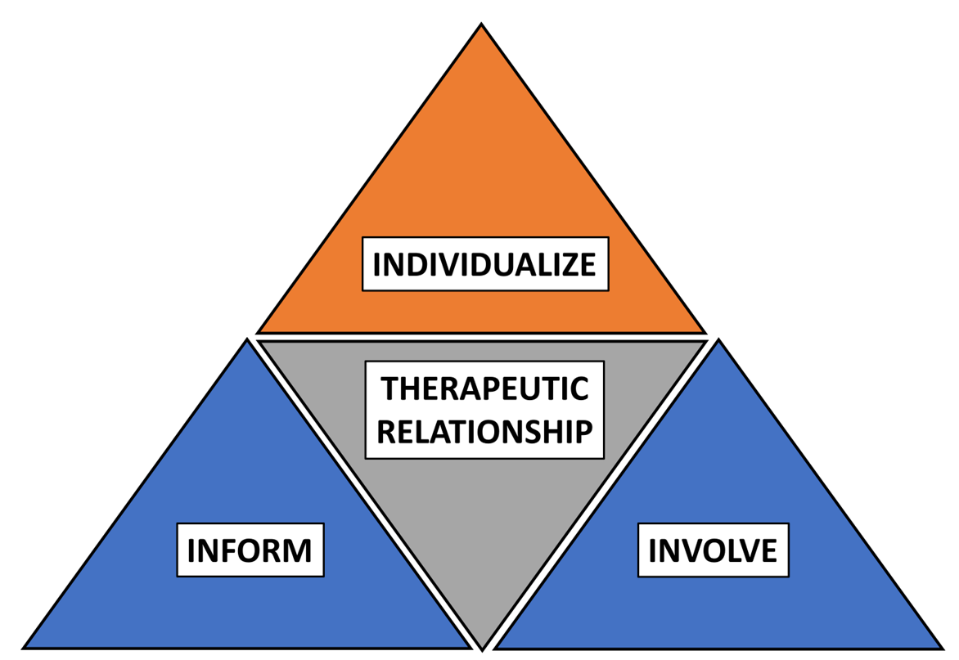

The second category identified related to maintaining a therapeutic relationship. Not surprisingly, this involves factors that have been reported in previous studies such as listening, being sympathetic, and showing emotional interest. Based on their findings, Grenness et al. (2014a) developed a simplified clinical model for operationalized patient-centered audiologic rehabilitation (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Clinical model for operationalized patient-centered audiologic rehabilitation where hearing aids are recommended (adapted from Grenness et al., 2014a).

Understanding Patient-Centered Care

What we have been discussing in this section all falls under the umbrella of patient-centered care. This concept has been discussed in medicine for decades but was not discussed much in the profession of audiology until the past ten years or so. Before leaving the topic, it might be useful to go a little deeper into this concept.

Grenness et al. (2014b) published an excellent review article on how patient-centered care can be applied in rehabilitative audiology. In this section, we will paraphrase much of their work. See their paper for more details and references. In their article, they address (and answer) five questions on this topic: What is patient-centered care? What are the outcomes of patient-centered care? What are the factors contributing to patient-centered care? How is patient-centered care measured? What are the implications for audiologic rehabilitation?

1. What is Patient-Centered Care?

Grenness et al. (2014b) define patient-centered care as the concept that patients should be encouraged to be active participants in their health care through the creation of a power-balanced, therapeutic relationship with their health professionals. This is contrary to the more traditional mode of health care, termed “practitioner-centered.” While there is not a well-defined model for patient-centered care specific to audiology, we can borrow from the field of primary care medicine, which was developed based an extensive review of empirical literature, and has five key components (Mead and Bower, 2000).

- Biopsychosocial perspective: Health care should take into account a person’s psychological and social states as well as the biological impact of the health condition.

- Patient as person: The health professional should try to understand the patient as an individual within his or her own context.

- Sharing power and responsibility: Importance is placed on the patient’s lay knowledge and self-expertise and encourages equality in power.

- Therapeutic alliance: The relationship between health professional and patient is important and has in itself therapeutic effects.

- Practitioner as person: The health professional brings value and subjectivity to the relationship; self-awareness is important

2. What are the Outcomes of Patient-Centered Care?

Grenness et al. (2014b) speak of the outcomes in three general categories: patient satisfaction, patient adherence and health outcomes, and practitioner outcomes.

Patient Satisfaction. Not surprisingly, numerous studies have reported an association between patient-centered interactions and improved patient satisfaction, although it’s important to point out that not all patients prefer this approach. We suggest that an agreement between the patient and the HCP regarding degree of the patient-centered approach, will help to maximize satisfaction.

Patient Adherence and Health Outcomes. We know that in most cases, adherence to treatment will result in better overall health outcomes. Involving the patients in decisions regarding their treatment has been found to improve adherence, increased self-management and the overall interest of the patient regarding their care.

Practitioner Outcomes. While we usually think of patient-centered care as a benefit for the patient, in many cases, benefits for the practitioner (HCP) also exist. For example, research shows that fewer malpractice cases are filed when patient-centered care was employed. And as you might expect, higher job satisfaction for the practitioner exists when the patient’s treatment adherence and outcomes are more positive.

3. What are the Factors Contributing to Patient-Centered Care?

Grenness et al. (2014b) list four categories of factors that reportedly influence the occurrence of patient-centered care: patient, practitioner, organizational, and research and implementation-related factors.

Patient-related Factors. Patient-related factors that have been found to influence the implementation of patient-centered care include (see Grenness et al., 2014b, for specific references):

- Gender: Women tend to be given more information, be asked more questions, and tend to respond in a more emotionally expressive style.

- Ethnicity: Caucasian patients receive more information, higher quality interpersonal connection, and more skilled questioning and empathy from their practitioner.

- Age: Older patients prefer, on average, a more paternalistic model of healthcare.

- Education: Patients with higher levels of education are more likely to be able to express their preference for involvement in decision-making to their practitioner and prefer a more patient-centered approach.

- Socioeconomic status: Patients from high socio-economic backgrounds made more attempts at active participation; patients from a lower socioeconomic background received less information and less partnership building attempts from their practitioners.

- Health status: Patients who report a better health status are more likely to receive a patient-centered interaction; patients with a lower health status acted more negatively and passively towards their practitioners.

Practitioner-related Factors. Female or Caucasian practitioners with more years of experience have been found to be more patient-centered; female practitioners seeing female patients more effectively used non-verbal cues and spent more time than with male patients. Male-male encounters yielded the least patient-centered interactions.

Organizational-related Factors. Most of the research in this area revolves around the length of the appointment. Studies have shown that patient-centered appointments do not necessarily take longer than practitioner-centered ones. While longer would seem better, two different studies have shown that the amount of time spent in an encounter was not linked to patient satisfaction (Grenness et al., 2014b).

Research and Implementation-related Factors. Most of the research regarding patient-centered care and audiologic rehabilitation has only occurred in the past ~20 years. The findings, however, are similar to that from medicine and other disciplines; trusting the practitioner, being informed and educated, and being provided with options. A separate study found that important concepts included the patients’ want for empowerment, for the audiologist to understand their needs, and their want to feel comfortable and be supported in shared-decision making.

4. How is Patient-centered Care Measured?

Grenness et al. (2014b) report that although patient-centered care has been studied for decades, there is no well-established gold standard for its measurement. Historically, methods usually have included observational techniques using audio or video footage, and patient or practitioner questionnaires—recall that we discussed the use of the Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS) earlier in this section. They note that over 50 instruments exist which examine the nature of the interaction through rating scales, checklists or verbal/non-verbal coding schemes. It is also helpful if the measurement of patient-centeredness is accompanied by a measure of its effect on outcome.

5. What are the Implications for Audiologic Rehabilitation?

There are some issues related to patient-centered care in audiologic rehabilitation that make it somewhat different than the application in general medicine. The most obvious, is that in most cases, the sale of hearing aids is part of the treatment process. It is very common, that this prompts the patient to enter into a discussion of cost (“I can get them for ½ the price at Costco”), which puts the HCP on the defensive, which can work against the goal of being a good listener and compassionate. Moreover, there are some dispensing offices that advance the practitioner-centered approach, as it is believed that this is more apt to result in more hearing aid sales.

With that said, Grenness et al. (2014b) had two general comments regarding increased implementation of patient-centered care for audiologic rehabilitation:

- Given that there is a lack of research in this area specific to our discipline, they believe that a definition of patient-centered care specific to audiologic rehabilitation is required, including qualitative studies that take the patient's perspective into account.

- Secondly, they suggest that through the identification of what patients want from audiologic rehabilitation, we can then investigate whether audiologic rehabilitation is patient-centered and identify the barriers and facilitators to its implementation.

Practical Applications of Patient-Centered Care

It probably goes without saying that hearing aid technology and testing are central to patient care; however, it is easy for audiologists to develop an over-reliance on them, and lose sight of the patient as a person – a person, who, according to the research cited in this section, wants a trusting relationship with their service provider. For example, Amlani (2016) found that “audiologists are falling short in creating a positive emotional communication relationship, which might be a factor in why impaired listeners are not adopting audiologic services and technology.” Although hearing care is a “technology-reliant” profession, there are a few simple things, based on the research reviewed here, HCPs can do to be more patient-centered.

- During the in-take appointment, collaborate with the patient on setting treatment goals. Record these goals on the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI; see Taylor & Mueller, 2023a). This collaborative process should permeate all appointments. As outlined by English (2022), there is a difference between standard instructions and joint goal setting. For example, at the initial fitting a standard instruction might look like this: “You will still have problems in noise. It’s unavoidable.” In contrast, joint goal setting for this standard instruction would sound like this: “It’s quiet in the fitting room right now, but let’s think about noisy situations for you. What might those be in your life? Let’s talk about some things you can do to improve communication there.” Notice that joint goal setting invites the patient to reflect on his own daily life experiences as part of the hearing aid orientation process.

- Encourage a family member to attend appointments with the patient. When making appointments say: “Our experience is that it is very helpful if you can bring a friend or a loved one along to the appointment. Who would that be?” If the patient asks for more information, we could say “There is a lot to discuss, and it helps to include family and friends in the process.”

- Ensure that the physical environment is comfortable for the patient and family members.

- Start off the appointment by encouraging dialogue and inclusiveness among all participants in the appointment by saying something like, “We are going to do a lot today. For the next 10 minutes, I want to find out about your hearing and communication (directed to the patient) and then I want to find out about this from your perspective [directed to the significant other].”

- Finally, at a minimum, we recommend that HCPs incorporate the Patient-Centered Observation Form (Cox, 2013) into their counseling approach with patients. This decision aid is a simple way to better inform patients about their treatment options and it allows for more dialogue about the pros and cons of these options.

8.4: During the Appointment: Assessment Tools Beyond Routine Audiometrics

In the previous section, we focused on the importance of patient-centered care, and how this approach will not only improve the HCP-patient relationship but is correlated to long-term patient satisfaction—including satisfaction with hearing aids. We can assume, that the more we learn about our patients during the pre-fitting process, and the better we understand our patients, the greater the probability that effective patient-centered care will result. We of course, historically, have focused on such measures as pure-tone thresholds and speech recognition testing as the cornerstones of our pre-fitting measures. Research tells us, however, that other measures—such as self-assessment scales—are equally, or maybe even more important in determining acceptance, use and satisfaction with hearing aids.

In previous volumes of Research QuickTakes, we have reviewed some popular pre-fitting scales related to the fitting of hearing aids. The most popular appears to be the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI)—see Taylor and Mueller (2023a), Research QuickTakes Volume 6 (Part 1) for review. This scale, indeed, is very useful for establishing fitting goals, measuring expectations and following hearing aid use, assessing real-world benefit. But there is much more to learn about the patient for effective treatment, and that is what we’ll discuss in this section. Fortunately, for most of our areas of interest, there is an evidence-based scale that can be used to collect meaningful information.

Perception of the Problem

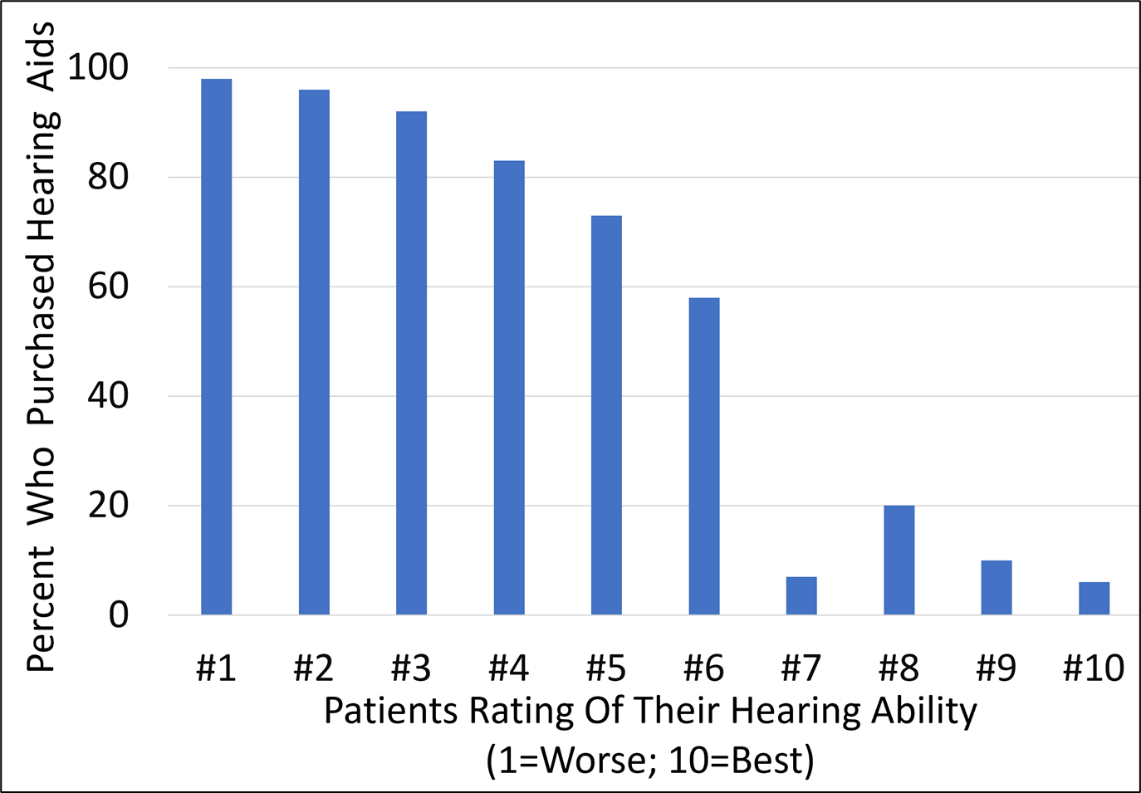

As we previously have reviewed, a measure of the patient’s perception of their hearing problem can be useful in both predicting the adoption of hearing aids, and also, hearing aid benefit—in some studies, as predictive as the measurement of hearing thresholds (e.g., Humes, 2023). Most of Humes' work relied on the HHIE/A (the 25-Question version), but we have a different scale that you might like, if for no other reason than it is only one question! In a retrospective study of over 800 adults, aged 18-95 years, Palmer et al.. (2009) examined the relationship between the patient’s rating of his or her hearing ability, and their subsequent decision to purchase hearing aids. The patient was asked the following question: “On a scale from 1-10, 1 being the worst and 10 being the best, how would you rate your overall hearing ability?”

The answer to the above question was then compared with whether the patient purchased hearing aids. The results are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Hearing aid purchase compared to rating of hearing ability. (Adapted from Palmer et al.., 1999).

As we would predict, those that rated their hearing very poorly (e.g., #1, #2 or #3), were very likely to obtain hearing aids—92% or greater. And only a small percent of those who stated that had relatively good hearing (ratings of #7 to #10) purchased hearing aids (20% or less). What perhaps is most interesting in the findings, is the large difference between the #7 rating (7%), and the #6 rating (58%). While only 1 increment apart, the purchase rate increases by 51%! Obviously, there is something about that rating level, which relates to going from contemplation and planning to “action.” This simple scale is just one example of how collecting additional information can be useful and does not always require much extra clinic time or effort.

More recently, a group of researchers affiliated with the VA system modified the Tinnitus and Hearing Survey (THS; Henry, et al. 2015) to quantify the degree of self-reported hearing difficulties in a group of young and middle-aged US Service Members. Comprised of the following four questions of the THS, the THS-H was completed by study participants in about 45 seconds.

- Over the last week, I could not hear or understand what others were saying in a noisy crowded room.

- Over the last week, I could not hear or understand what was being said on TV or in movies.

- Over the last week, I could not understand people with soft voices.

- Over the last week, I could not understand what was being said in a group conversation.

Unlike the original THS, which was designed to triage hearing loss and tinnitus as the primary condition to treat, the THS-H scores each of these questions on a 0 to 10 scale, with 0 “being not a problem” to 10 “being a very big problem.” Based on their statistical analysis, only 5% of Service Members surveyed with clinically normal hearing scored above 27 on the 4-question TSH-H. Thus, a score of 27 was selected as a cutoff for “clinically significant hearing problems” (Davidson, et al., 2023).

In a related study, Davidson, et al. (2024) surveyed 186 Service Members (average age ~35) who were dispensed hearing aids for either amplification or tinnitus relief. They divided the respondents into four groups:

- Hearing loss and no self-reported hearing difficulty

- Hearing loss and self-reported hearing difficulty

- Normal audiogram and no self-reported hearing difficulty

- Normal audiogram and self-reported hearing difficulty

They found that individuals in the normal hearing/self-reported hearing difficulty group (#4 above) were the most likely to wear their hearing aids. Further, 95% of those self-reporting hearing difficulties said they wore their hearing aids every day, and those with no self-reported hearing difficulty, regardless of hearing loss, were highly likely to discontinue hearing aid use within a month or two. Because it takes less than a minute to complete, and identifies individuals with “clinically significant hearing difficulties,” we think the THS-H would be a useful tool for identifying patients with subjective hearing difficulty that might benefit from audiologic intervention.

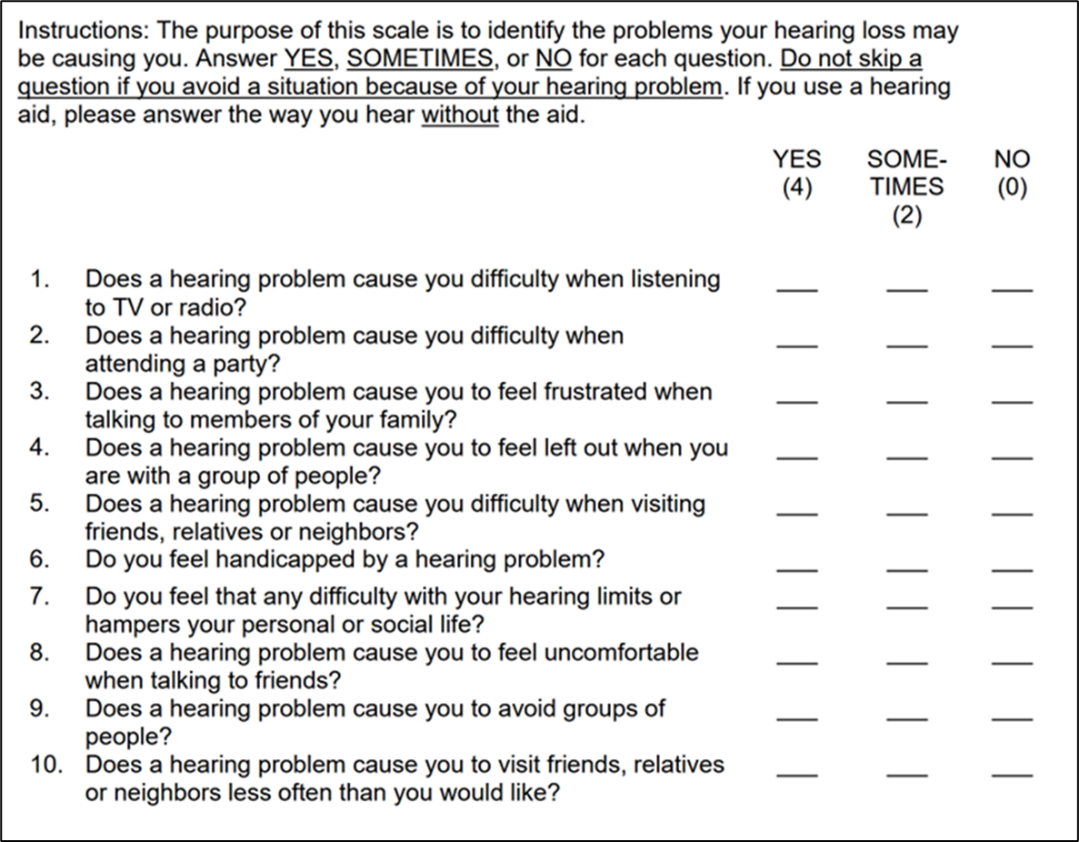

Social and Emotional Impact

We’ve talked about the HHIE/A self-assessment scale in earlier Research QuickTakes. This is one of the first scales to be used frequently in clinics and research and includes statements that the patient rates relating to both social and emotional aspects of having a hearing loss. To refresh your memory, historically, the HHIE (E=Elderly) was for people 65 or older, and the HHIA (A=Adult) were for patients under the age of 65. In recent years, these scales have been merged and a new 18-item scale is available: Revised Hearing Handicap Inventory (RHHI; Cassarly et al.., 2020). There also is a 10-item screening version that has been shown to have acceptable reliability for clinical use (RHHI-S; see Figure 12). For the screening version, if a score of 6 or higher is obtained, a hearing problem is expected.

Figure 12. The Revised Hearing Handicap Inventory, Screening version (RHHI-S; Cassarly et al., 2020)

Like its predecessors, the RHHI is composed of statements related to both the social and emotional aspects of having a hearing problem. Examples from the RHHI-S:

- Social: Does a hearing problem cause you difficulty when attending a party?

- Emotional: Does a hearing problem cause you to feel uncomfortable when talking to friends?

In the earlier versions of the HHIE/A, each item was labeled as either being emotional or social (e.g., S-1, E-2, S-3, etc.), so that separate scores could be obtained if desired, although it was uncommon for there to be a significant difference between these items, and nearly always, at least in the clinic, a combined score was used. As you can see on Figure 12, this “E” and “S” labeling has not been carried over to the RHHI.

Timmer et al. (2023) reviewed the importance of considering the social-emotional well-being of our patients. Based on HHIE-S scores, they developed an Auditory Wellness Rating Scale: 0-2 Excellent; 4-6 Good; 8-14 Fair; 16-22 Poor; 24-40 Very Poor. For the various ratings, they provided action-oriented recommendations (see article for details). The authors suggest a five-step approach the help ensure the social-emotional well-being of our patients.

Step 1: Identify the patient’s social-emotional well-being.

Step 2: Include family members in audiologic rehabilitation.

Step 3: Incorporate social-emotional needs and goals in an individualized management plan.

Step 4: Relate the identified hearing needs and goals to recommendations: hearing devices, auditory, communication and social training.

Step 5: Use counseling skills and techniques to explore and monitor the patient’s social-emotional well-being.

Locus of Control

Locus of control is considered to be an important aspect of personality, and the concept has been studied since at least the 1960s (Rotter, 1966). Locus of Control (LOC) refers to an individual's perception about the underlying main causes of events in his or her life. That is, do you believe that your destiny is controlled by yourself, by external forces (e.g., God, powerful others), or things just happen by fate? In the world of health, Health-LOC refers to people's attribution of their own health to personal (Internal) or environmental factors (External). We talk about this briefly in Research QuickTakes Volume 5 (Taylor & Mueller, 2023b).

Based on the results of self-assessment questionnaires, HLOC often is classified into the three different dimensions we mentioned earlier: internality, powerful others, and chance. A patient’s locus of control is related to their self-efficacy. This is the belief that you can produce the result you want in a specific area—how much control you feel like you have over a situation. People with high self-efficacy for a task will most likely have an internal locus of control for success in that task. It’s easy to see why this internal trait might be related to the adoption and use of hearing aids. In general, a more internal LOC is seen as desirable; we know that as people get older, they tend to become internal, and people higher up in organizational structure are more internal. It is a bit more complicated, however, as an internal LOC needs to be matched with competence, self-efficacy, and opportunity. If not, internals may struggle. On the other hand, externals might be more be more relaxed and lead a happier life, as they don’t have the burden of being in control of their life.

As we mentioned, self-efficacy is a desirable trait for someone obtaining hearing healthcare, such as the use of hearing aids. There has been limited research, however, in this area related to LOC. In one study, Cueval et al. (2019), surveyed a total of 114 persons who identified as hard-of-hearing. These authors found that a strong predictor of self-efficacy for this group was an internal locus of control. They suggest that individuals who are hard-of-hearing with both an internal locus of control and high self-efficacy may adjust to live better with their hearing loss (and presumably the use of hearing aids).

HLOC also has been studied to some extent in research that sought to identify factors that are associated with the ability to successfully set up a pair of commercially available self-fitting hearing aids (Convery et al., 2019). The self-fitting procedure required participants to customize the physical fit of the hearing aids, insert the hearing aids into the ear, perform self-directed in-situ audiometry, and adjust the resultant settings according to their preference. Forty-one (68%) of the participants achieved a successful self-fitting. Those who needed help from an HCP were more likely than those who self-fit independently to have an HLOC that was external. We can expect those patients with high self-efficacy and an internal locus of control to be the most successful with self-fitting. While it was not part of the study, we might guess that those with an internal HLOC would be more likely to sample the OTC marketplace.

Empowerment

We have been talking about the importance of self-efficacy, and closely related to this is empowerment. McAllister et al. (2012) address empowerment as it relates to healthcare, and they define it as “an individuals’ capacity to make decisions about their health (behavior) and to have or take control over aspects of their lives that relate to health.” Bennett et al., 2024, point out that empowerment has gained more prominence in healthcare as we have moved to a more biopsychosocial model. Patients can be empowered by their healthcare providers through education, counseling, and patient-centered care, or patients can empower themselves through self-education and help-seeking. The authors add that research shows that empowered patients have a greater understanding of how to navigate the healthcare system, experience improved health outcomes, and are more satisfied with the healthcare they receive. If that sounds familiar, these benefits are very similar to what we discussed earlier in our section on patient-centered care.

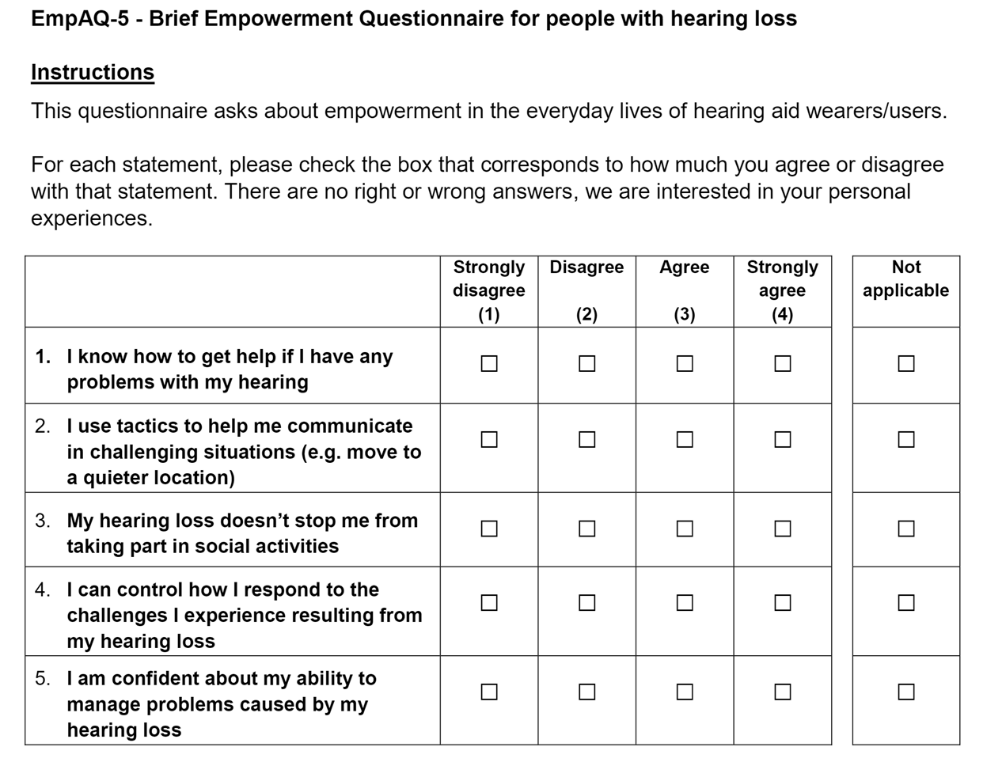

While empowerment is not commonly measured during an audiologic visit, that might change, as Bennett et al., 2024 have developed a self-assessment measure that might appeal to busy clinicians—it’s only 5 questions! The scale is shown in Figure 13. While the instructions state that the scale is for hearing aid wearers/users (see Figure 13), we believe that this scale also could be used for anyone with a hearing loss, as none of the 5 questions specifically relate to the use of hearing aids.

Figure 13. Abbreviated scale of empowerment (adapted from Bennett et al., 2024a).

The authors started with a 33-item empowerment scale, and as you might guess, considerable data analysis was required to obtain a 5-item scale that was valid and reliable—if you’re interested in the process, they explain it nicely in their 16-page Ear and Hearing article (Bennett et al., 2024). We should mention that their work also resulted in a 15-item scale (The EmpAQ-15 and EmpAQ-5 can be freely downloaded from https://osf.io/caj84/). The five question EmpAQ-5 evaluates five separate domains of empowerment: knowledge, skills, participation, control, and self-efficacy. We believe the EmpAQ-5 could be a valuable tool that can be used clinically to gauge just how empowered a patient might (or might not) be on the day of their appointment. This might be particularly useful during an initial appointment or even before the patient has had their hearing tested. Say, for example, your patient self-rates any of these five domains a one or a two on the 5-item scale. This provides valuable insights on exactly what “areas of concern” the HCP should address before hearing aids are fitted, or even months or years post-fitting. Given its brevity, the EmpAQ-5 might be a good questionnaire to administer during annual follow-up appointments in order to pinpoint problems that are getting in the way of successful outcomes.

Self-Esteem

It’s well known that non-audiologic factors, such as personality traits, can have a significant effect on satisfaction with using hearing aids. One of the first studies to examine this extensively, was the work of Robyn Cox et al. (2005). Self-report data were obtained from 230 older adults with bilateral hearing loss. All participants were seeking new hearing aids, and they completed a comprehensive personality questionnaire (NEO-Five-Factor Inventory) as well as questionnaires determining locus of control and preferred coping strategies. Interestingly, these researchers found that individuals who seek amplification are not simply a random sample of the general population, and moreover, also not a random sample of the hard-of-hearing population. Cox et al. (2005) found that hearing aid seekers tended to be more pragmatic and routine-oriented. These individuals also were found to feel relatively more personally powerful in dealing with life's challenges and reported using social support coping strategies less frequently than their peers.

Related to, and in agreement with the findings of Cox et al. (2005) is our previous discussion of empowerment and self-efficacy. We’re now going to add yet another personality trait—self-esteem. While seeming similar to self-efficacy, self-esteem refers to your respect for your own value and worth, whereas self-efficacy refers to how you feel about your ability to succeed in different situations. A person could have low self-esteem, but yet have high self-efficacy for some aspect of their life. In general, high self-esteem is associated with good coping skills and persistence—two factors that would seem to relate to the use of hearing aids, and indeed, this has been studied.

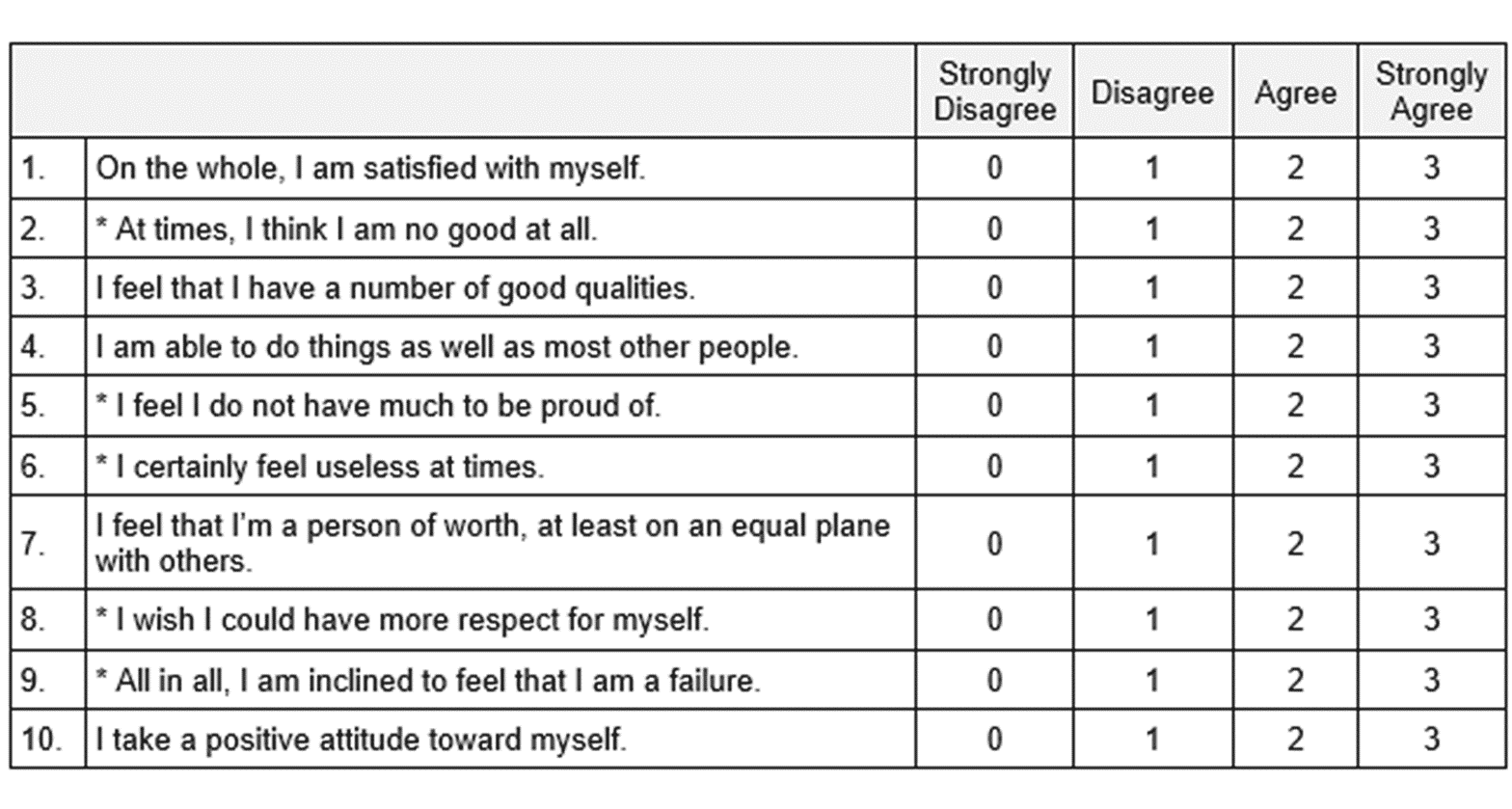

In a recent publication, Ceyhan and Ture (2023) conducted testing with 86 hearing aids users, which included a measure of self-esteem, and hearing aid satisfaction was assessed using the IOI-HA outcome measure (see QuickTakes Volume 6 (Part 2) for review of this scale; Taylor & Mueller, 2023c). Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale was used (see Figure 14). This is a 10-item scale; 4-point Likert, containing 5 positive and 5 negative items. Scores on the sale range from 0-30. Typically, scores between 15 and 25 are within normal range; scores below 15 suggest low self-esteem. Interestingly, given that scores greater than 25 are not in the “normal” range, this suggests that having “too much self-esteem” isn’t good either. An alternative method of interpreting the findings: 21-30 points: High self-esteem; 15-20 points: Moderate self-esteem; and 0-14 points: Low self-esteem.

Figure 14. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (adapted from Rosenberg, 1965).

There was a significant positive relationship between the level of satisfaction with hearing aids (IOI-HA score) and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale Score (p<.001); self-esteem explained 26.2% of the variation in satisfaction. The authors conclude that the self-esteem of hearing aid users is a prominent factor in satisfaction with hearing aids, and important for enriching audiologic rehabilitation (Ceyhan & Ture, 2023).

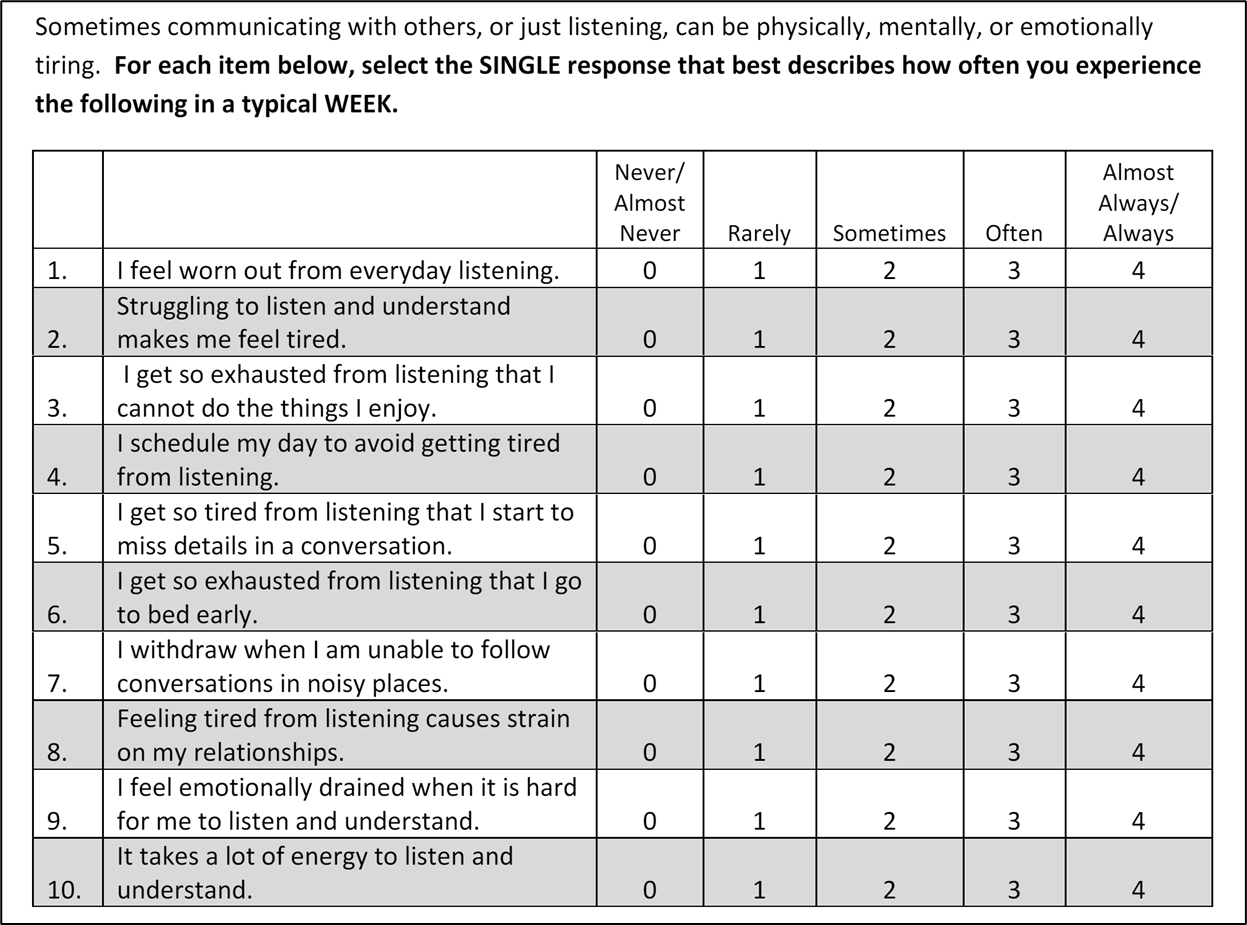

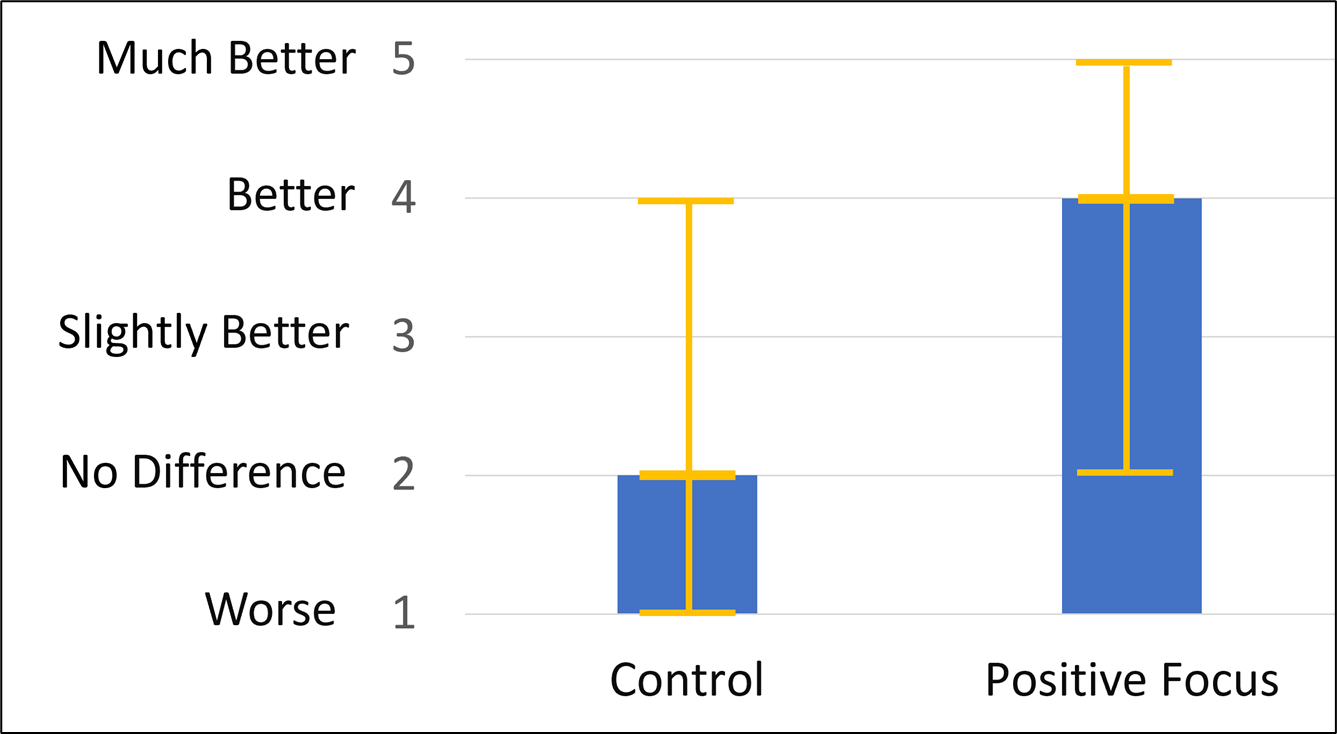

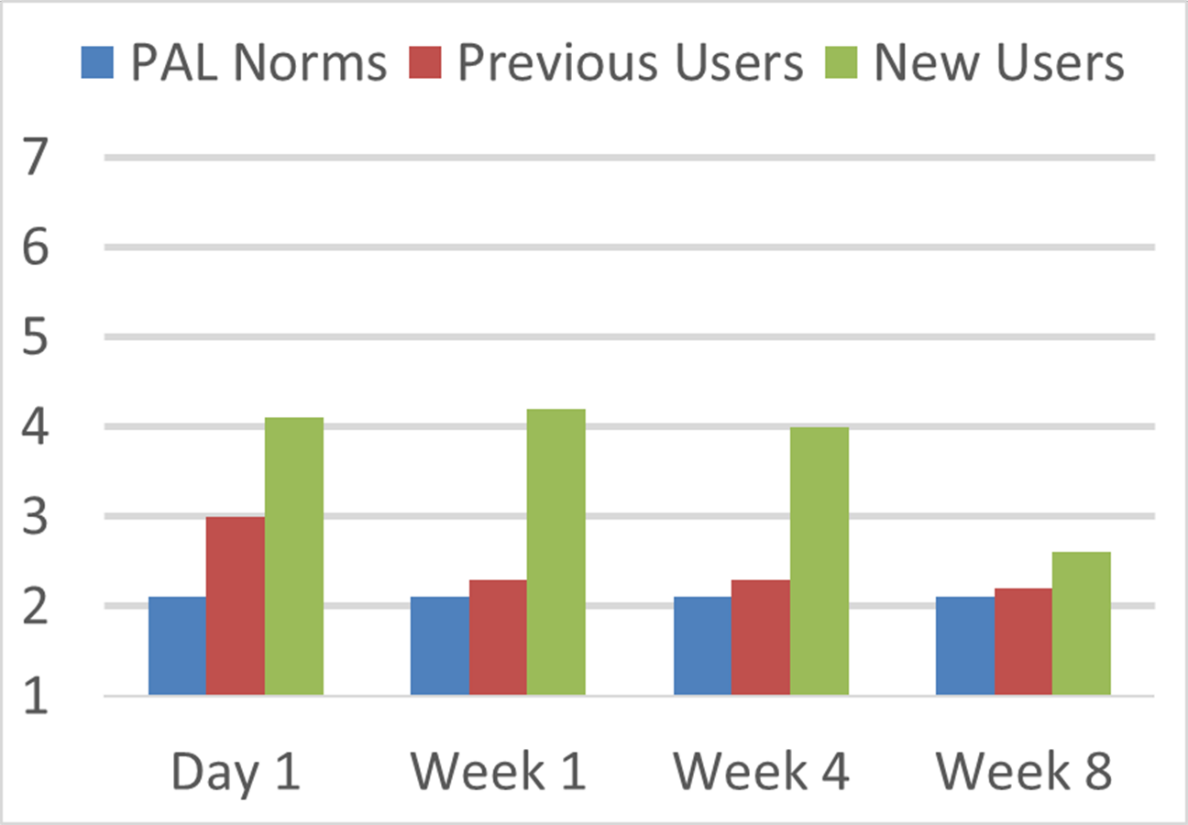

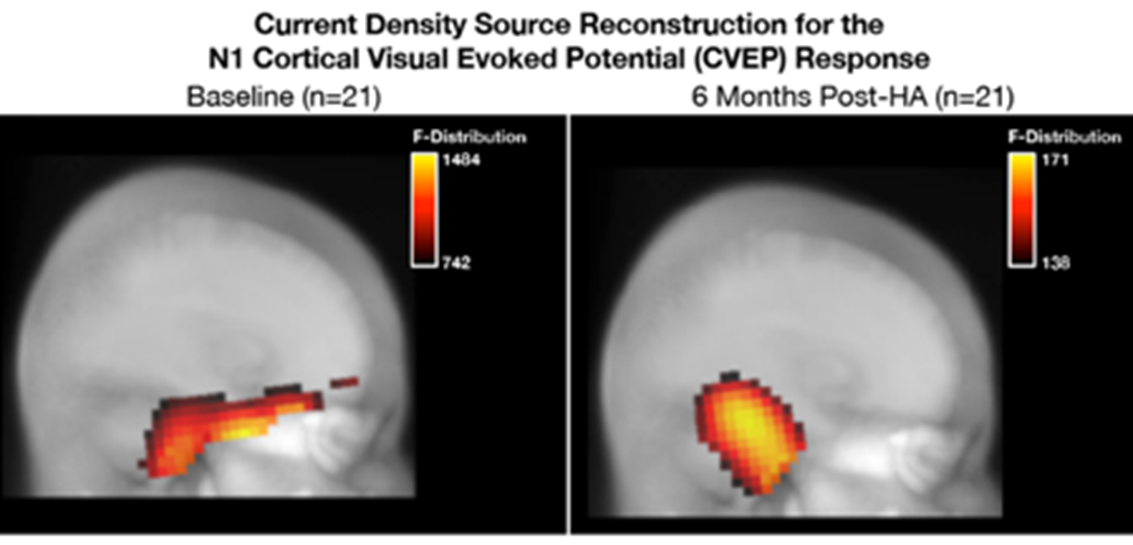

Listening Fatigue