Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Define the dynamics of group conversations and how these dynamics fail as a function of hearing loss.

- Describe four tactics that clinicians can leverage to improve performance for hearing aid wearers and their communication partners in conversations.

- Describe how conversations are important to human connections and relationships.

The spontaneous, often rapid fire, back and forth between listening and talking presents one of the greatest challenges for hearing aid wearers and their conversation partners. Here, we suggest that conversations are a special form of communication that are fundamental to the human condition. We also shed light on the obstacles associated with successful conversations for persons with hearing loss as well as offer practical, evidence-based solutions on how audiologists can improve hearing aid benefit for patients – in all types of group communications, from serious deliberations to playful banter.

What is the Secret of a Long, Happy Life?

Human beings are social creatures who, thanks in large part to the marvels of modern medicine and public health initiatives, expect to live a vibrant, active life well into their tenth decade. After all, isn’t 60 the new 40? Hence, any data that sheds light on the question, what is the secret of a long, happy life?, serves as a great starting point for understanding the expectations of persons with hearing loss who are seeking help from audiologists.

So, what is the secret of a long, happy life? The answer to this question has been on the mind of researchers for more than 80 years, and the answer, which is revealed at the end of this section, forces audiologists, we think, to be both holistic and tech-savvy in their approach. There are many longitudinal studies, conducted all over the world on a range of diverse populations, that help us address this question. Seven of these studies are summarized below; surprisingly, all find the same general conclusion.

Study 1 Harvard Grant Study

- Study began in 1938 by following 238 men enrolled at Harvard, since then the study has expanded to include thousands of individuals from diverse backgrounds.

- Still following the original 238 men through college graduation, marriage, war, parenthood, life crises, and old age – and has collected a wide range of data about the men’s physical and mental well-being

Study 2 British Cohort Studies

- 5 large nationally representative groups comprised of 17,000 individuals per group, started in the 1960s.

- Followed from birth throughout their lives collecting information on education and employment, family and parenting, physical and mental health, and social attitudes, as well as applying cognitive tests at various ages

Study 3 Cal Berkeley Mills Longitudinal Study

- A 50-year investigation of adult development that has followed a group of women since they graduated from Mills College

- Study is evaluating aging process on personality types, personality change and development, work and retirement, relationships, health, social and political attitudes, emotional expression and regulation, and wisdom

Study 4 Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health & Development Study, New Zealand

- Following the lives of 1037 babies born in 1972 and 1973

- Seeks to answer questions about how people's early years impact mental and physical health as they age

Study 5 Kauai Longitudinal Study

- Following the lives of a multi-racial cohort of 698 children born on the Hawaiian island of Kauai in 1955

- Examining differences in vulnerability and resilience and a goal to identify protective factors within the children, the family, and the cultural and caregiving environment across the lifespan

Study 6 Chicago Health, Aging & Social Relations Study

- A study of 229 Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic men and women who ranged from 50-68 years of age at baseline, beginning in 2002

- Analyses of demographic factors, health, cognitive function, loneliness, and social contacts

Study 7 The Baltimore Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Lifespan

- An interdisciplinary, community-based, longitudinal epidemiologic study examining the influences of race and socioeconomic status (SES) on the development of age-related health disparities among socioeconomically diverse African Americans and whites in Baltimore.

- Adults aged 35-64, followed since 2004.

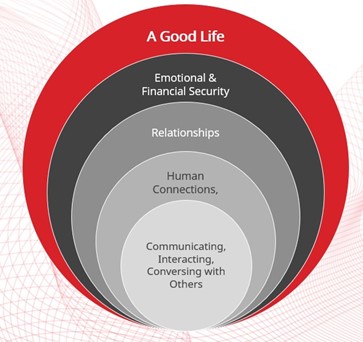

Now to the unifying conclusion of these seven studies. Although emotional and financial security are important components of a long, happy life, they are not the main factors. Instead, the answer can be summarized in three words: Relationships, relationships, relationships! It is the power and need for human connection that helps us live a good life as we grow older. As the current director of the Harvard Grant Study, Robert Waldinger, MD, says, “Loneliness kills. It’s as powerful as smoking or alcoholism.” Stated differently, it is the absence of human connections that often leads to social isolation, loneliness, and an overall poor quality of life. As several recent studies make clear, untreated hearing loss is linked to all these conditions. (See Shukla, et al., 2020 for a review). What profession is better equipped to help an aging population (re)discover, and then lead, their best lives than Audiology? You can think of each patient seen in the clinic as having their own red dot like the one shown in Figure 1. The job of the audiologist, through their in-take interview and assessment process, is to understand what goes inside each help seeking individual’s red dot.

Figure 1. Each patient has their own red dot that defines their version of a long, happy life. The role of the audiologist is to discover with is inside each person’s red dot

By virtue of the time we spend with patients, trying to understand what is inside their own red dot, audiologists are uniquely equipped to be a driving force for healthy and successful aging. As Figure 2 illustrates, the kernel inside the red dot are all the components of thriving relationships: human connections, communicating, interacting and conversing with others. Essential elements of the human experience that audiologists restore through their management and treatment of hearing loss.

If we are to believe the unifying conclusion of these longitudinal studies --- that the secret of a long, happy life is as simple as having and maintaining human connections with other people, then it is imperative for audiologists to understand the dynamic elements of spontaneous, improvisational, spur-of-the-moment communication. As it is abundantly clear that for human relationships to flourish, good hearing is essential. Our objective here is simple: Through a more detailed understanding of the dynamics of conversations and how hearing loss affects them, audiologists will be better equipped to deliver better, more holistic, more tech-savvy care in the places that underpin thriving relationships, namely social and workplace situations with one or more talkers.

Figure 2. The kernel of a long, happy life are human connections. The ability to communicate, interact and converse with one another is a foundation of these connections.

What are Conversations, and Why are They Important to Us?

Unlike other forms of human interaction, conversations are almost completely dependent upon hearing what other communication partners are saying. They usually involve an improvisational back-and-forth with an endless palette of topics, a broad range of objectives and spoken language. After all, you can silently read text messages or activate the closed captioning system on your television to gather meaningful information; but for conversations, the ability to hear what is said is necessary. For these reasons, a conversation is a special form of social interaction that demands cooperation between its participants.

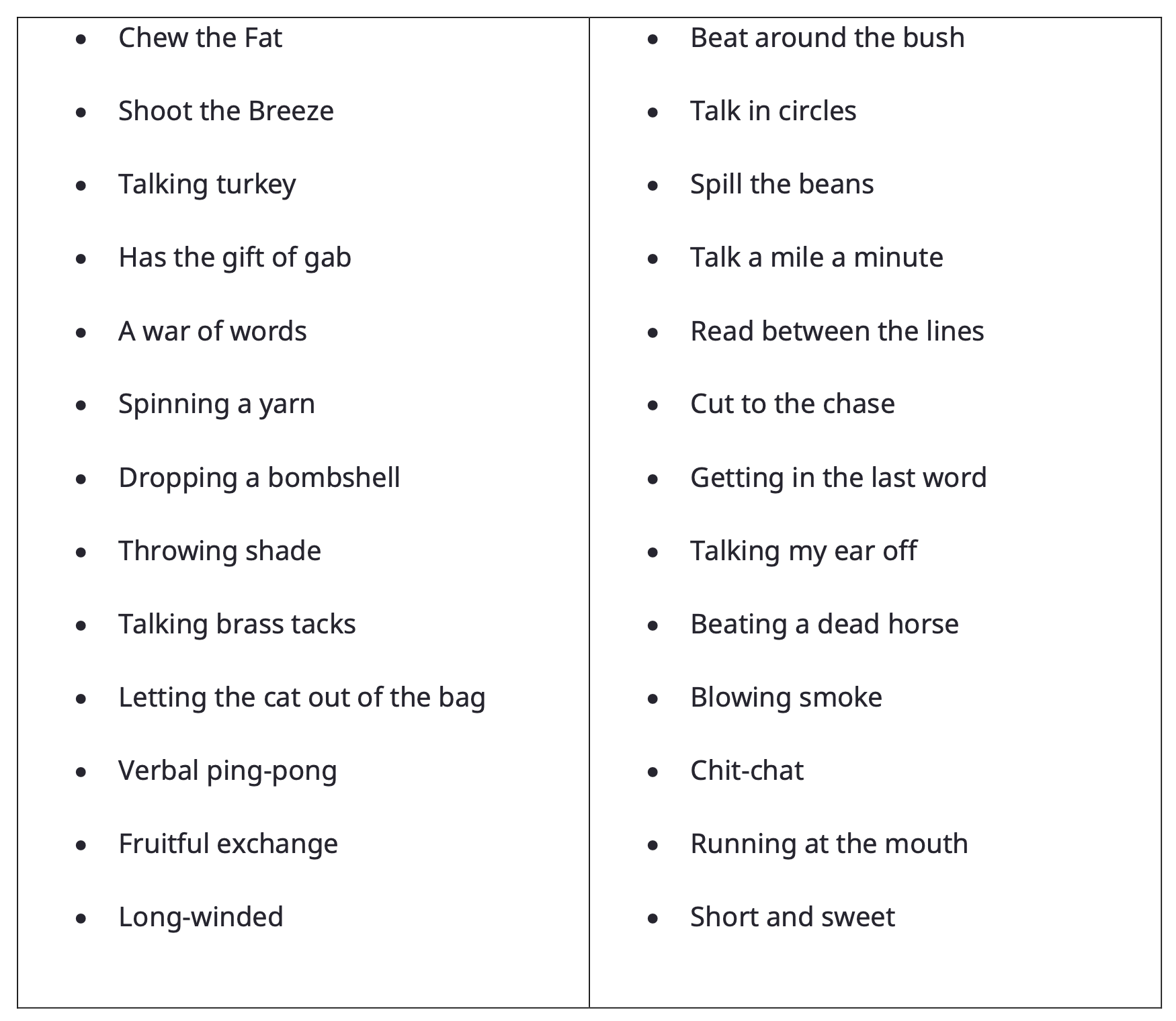

Beyond the mechanics of conversations, people use an astoundingly large number of colorful expressions to describe conversations, some of which are illustrated in Table 1. In view of the enormous number of colloquial terms, it is easy to see why conversations, like food and water, are often considered the lifeblood of human existence. These terms capture various nuances of conversation, ranging from formal discussions to improvisational chit-chat, and illustrate the important nature of conversations in our lives. It seems there is a memorable turn-of-phrase to describe any type of conversation.

Table 1. Some examples of colorful expressions used to describe conversations.

Work outside of the profession of Audiology further drives home the point that conversations are an essential part of the human experience, and our ability to fully participate in them is strongly impacted by hearing loss. According to Berth Danermark (2014), a professor emeritus of Sociology at Örebro University in Sweden, there are five unique elements of human conversation. One, there is a spontaneous flow and rhythm of utterances that occur in a natural and logical sequence. Two, a conversation always has a context. Conversations are always about something that all participants implicitly agree on. Three, all the participants in the conversation create its meaning: We ask questions, nod our heads and use various expressions to ensure the other participants that we are following along. Four, the work of the conversation – who does the speaking and when – is distributed equally among the participants. Five, there is a range of gestures, body language, and tone (metalanguage), which is dependent upon cultural mores, that everyone in the conversation uses. Human beings innately use these five elements to participate in conversations, but when hearing loss occurs, all these elements are affected.

Much of our health and well-being is dependent upon our ability to express ourselves using conversational skills. And when we lose these skills because of hearing loss, there can be significant consequences. Further work by Danermark (2014) indicates there are several possible emotional and social consequences associated with hearing loss and its effect on conversation ability. Some of these consequences include anxiety (uncertainty about how conversations will unfold), negative self-image (e.g., guilt and embarrassment), negative emotions (e.g., frustration, annoyance, anger), fatigue and stress, and sometimes social isolation and loneliness. Although these consequences are well-documented in the Audiology literature (Bott & Saunders, 2021; Holman et al. 2023; Hornsby et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2024;), audiologists rarely assess them.

In related work, Nicoras et al. (2022), used concept mapping to better understand and define conversation success. Thirty-five adults with normal and impaired hearing participated in their study. They identified seven clusters that contribute to conversation success: 1.) Being able to listen easily, 2.) Being spoken to in a helpful way, 3.) Being engaged and accepted, 4.) Perceiving flowing and balanced interaction, 5.) Sharing information as desired, 6.) Feeling positive emotions, and 7.) Not having to engage in coping mechanisms. According to their analysis, being able to listen easily and being spoken to in a helpful way were the most important elements of conversation success for participants with both normal hearing and hearing loss. These results demonstrate that conversation success in both group and one-on-one situations is complex with several interconnected elements involving all conversational partners.

To better understand these interconnected elements and the adaptations required of persons with hearing loss, it is helpful to look more carefully at the mechanics of conversations. As summarized by Petersen et al. (2022), there are five conversational dynamics that underpin the success (or lack thereof) of conversations.

- Alterations in speaking level

- Rate of speaking

- Turn-taking behavior

- Utterance length

- Speaking time

Petersen et al. (2022) examined the effects of hearing aids and noise on conversational dynamics between individuals with normal hearing and those with hearing loss while engaged in a two-person conversation. They observed that the person with normal hearing adapts their speech to reduce the communication difficulty experienced by their communication partner with hearing loss. They found that the person with normal hearing tends to speak louder in quiet and noisy situations (the well-known Lombard Effect), reduce the rate of their speech, and alter the spectral content of their speech. Simultaneously, during conversations, persons with hearing loss showed a larger variability in turn-taking timing, taking up more speaking time, and having longer turn-durations at high noise levels, which resulted in the communication partner with normal hearing to speak louder, especially at low noise levels. They also observed that persons with hearing loss initiated their turns faster, not slower, than the communication partners with normal hearing.

Additionally, when the older person with hearing loss is provided hearing aids, the communication partner wearing hearing aids reduces the duration of their utterances, speaks at a faster rate and lowers the intensity level of their voice. Interestingly, when hearing aids are worn by the communication partner with hearing loss, it has an impact on the normally hearing communication partner’s conversational success, too. Results showed the communication partner with normal hearing also lowers the intensity level of their voice when their communication partner is wearing hearing aids. Consequently, conversational dynamics are altered for all communications partners during one-on-one conversations.

Petersen (2024) furthered this research by investigating conversational dynamics in groups of three people consisting of two normal hearing persons and one individual with hearing loss. She investigated the impact that background noise, hearing loss and hearing aid signal processing had on conversational dynamics. The study was conducted in listening situations with low (50dB SPL) and high (75dB SPL) noise levels. In conversations at low noise levels, the communication partner with hearing loss was either unaided or aided, and at high noise levels, the communication partner with hearing loss used omni-directional or directional processing. Results showed that communication partners with hearing loss spoke more and initiated their turns faster, but with more variability than communication partners with normal hearing. As expected, when the noise level was increased from 50 to 75 dB SPL, it yielded higher speaking levels, but more so for the normal hearing communication partner. At low noise levels when the person with hearing loss wore hearing aids, both hearing impaired and normal hearing communication partners spoke louder; however, at high noise levels when directional processing was used, it only reduced the speaking level of the communication partner with hearing loss who was using hearing aids. Thus, the intensity level at which communication partners speak was observed to be the aspect of conversational dynamics most sensitive to hearing aid use in situations with three people conversing. Specifically, Petersen (2024) found that when the noise level increased from 50 to 75 dB SPL, the increased noise level caused communication partners to speak about 8 dB louder, which resulted in a reduction in the signal to noise ratio (SNR) from +11 dB SNR in the 50 dB SPL listening situation to a -6 dB SNR in the 75 dB SPL listening situation. The latter SNR in loud environments of -6 dB is in good agreement with the research of Beechey et al (2020) who measured a -5 dB SNR in a 77 dBA café noise listening situation.

These studies underscore the nature of human conversations: They are complex and consist of linguistic, auditory, and visual components that require all their participants, not just the person with hearing loss, to adapt to overcome communication challenges. Most importantly, conversational ability is crucial to quality of life and wellbeing because it enables individuals to connect with others, share experiences and build relationships – all vital for emotional support and mental health. The ability to effectively participate in conversations can enhance a person’s sense of belonging and reduce their feelings of isolation and loneliness. Not only does the secret of a long, happy life reside in our ability to maintain relationships – a characteristic of the human condition dependent in part upon good hearing, but it relies on the audiologist’s ability to restore active participation in conversations for help seeking individuals and their communication partners. To that end, the next section explores how audiologists can leverage these insights on conversations in the selection and fitting of hearing aids.

How Can Audiologists Leverage Conversation Research to Better Serve Patients?

Since conversations are a special form of human interaction, it’s helpful to approach them with a bit of special attention in the clinic. This section outlines four tactics and considerations audiologists can use to improve hearing aid outcomes in conversational situations.

Patient Expectation Worksheet (PEW)

Given the challenges associated with fully participating in conversations, audiologists would be wise to carefully construct personalized treatment goals that are aligned with these challenges. The Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) (Dillon et al 1997) is a popular tool used to target these individualized goals during the initial help seeking appointment. Simply targeting two or three listening situations and recording them on the COSI, while better than nothing, might fall short of patient expectations when trying to optimize outcomes in conversational situations. Instead, audiologists are encouraged to implement an approach, introduced by Palmer and Mormer (1999), referred to the Patient Expectations Worksheet (PEW), which uses the same 1 to 5 scale as the COSI. In a collaborative manner, the audiologist first asks the patient to target two to three listening situations in which conversations present a challenge where hearing aids would be of help. These goals are recorded on the PEW. Next, after these goals have been recorded on the PEW, the patient indicates how often he is successful in the situation currently (C), prior to hearing aid use, and how he expects to function after the intervention (E). The audiologist marks the PEW with an X-mark (“x”) to indicate what she believes is a realistic expectation given the individual characteristics of the patient (audiologic and non-audiologic information).

If the “E” and “X” are not in agreement, the audiologist counsels the patient until he understands why their expectations might be too high or too low, or how the planned intervention ought to be modified to better meet the expectations of the patient. Interventions are planned based on the identified goals and the audiologist creates ways to measure each functional goal. Figure 3 shows an example of a completed PEW in which the patient’s expectations and the audiologist’s judgments of success are fairly well aligned.

Goal | Hardly Ever | Occasionally | Sometimes | Most of the Time | Almost Always |

To participate in social situations with friends |

|

C |

|

X |

E |

To gossip with my neighbors on the back porch without having to strain or repeat |

C |

|

|

X |

E |

Figure 3. An example of the completed PEW where treatment goals, expectations are recorded. Expectations of the patient are compared to how the audiologist believes the patient will be achieved post intervention. C = how patient rates their current ability to communicate, E = how the patient expects to communicate post-intervention, X= audiologist’s judgment of what outcome the patient will achieve. Note in this example how patient expectations and audiologist expectations are closely aligned.

Occasionally the “E” of the patient and “X” of the clinician will not agree. In practical terms, this occurs when the “E” and “X” are separated by two or more categories. For example, the patient may state his expectations in the “almost always” category, while the clinician believes that realistic expectations fall in the “sometime” category. When expectations don’t align, the audiologist counsels the patient until he understands why his expectations might be too high or too low. Alternatively, when patient and clinician cannot align on expectations, a conversation about modifying the planned intervention must take place. In a later section we discuss supplemental technologies which could be recommended when expectations between the patient and audiologist are misaligned.

A critical part of conducting the PEW is the clinician’s ability to determine or predict the outcome of each targeted goal on the 1 to 5 scale. This determination relies on sound clinical judgement and experience. However, the clinician should use the results of objective tests like the pure tone audiogram and Quick SIN, as well as familial support and the patient’s perceived attitude toward wearing hearing aids when deciding where to place the “X” on the 1 to 5 scale.

Considering the impact of hearing loss on various conversational dynamics such turn-taking and speaking time, which affect communication partners, the PEW can also be completed by them. Once a series of goals has been targeted, communication partners can be asked to rate, from their perspective as interlocutors, their own current ability (“C”) and then to share their expectations (“E”) relative to each of the targeted goals. Besides getting communication partners involved in a collaborative process, which is a cornerstone of person-centered care, involving them in the PEW reflects their essential role to conversation success.

Fit Signia Multi-Stream Technology: How it works?

In 2023 Signia launched a novel multi-stream technology, Signia Integrated Xperience (IX), with a feature known commercially as RealTime Conversation Enhancement (RTCE). This technology, specifically engineered to optimize performance in multi-talker situations, relies on an acoustic scene analysis that estimates the locations of nearby talkers (i.e., conversation partners in proximity) and is computed as follows: The microphone signals are analyzed continuously to detect whether relevant speech is present in front of the wearer area (within a viewing angle of approximately ±70°), and then an acoustic proximity detector algorithm is applied to evaluate the relevance of the speech. This detector is designed to differentiate between relevant speech coming from conversation partners in proximity to the wearer and irrelevant speech such as voices in the background (e.g., babble noise in a restaurant) or distinct talkers that are far away from the relevant conversation partners. This detector takes the incoming microphone signals and estimates the directional power content (i.e., content of highly correlated signals) and the diffuse babble noise power content in the current noisy situation. If the directional power content is above the diffuse noise power content, then directional (nearby) speech is detected and considered relevant. Subsequently, a localization feature is enabled where each talker position is determined. This localization is performed by processing the binaural microphone signals using several fine-tuned spatial filters in parallel. Those spatial filters are designed to be responsive at different angles in the front area. In combination, the filters constitute a high-resolution angular grid, which determines the location of the talkers communicating with the wearer by analyzing the results of the spatial filters’ values, that is, determining the most responsive filters. Afterward, the processor uses multiple front-facing monaural and binaural beams steered toward the determined directions containing speech, with all beams active simultaneously and considering the conversation dynamics. While the multiple front-facing beams are optimized for multiple speakers in group conversations, the rear-facing beam emphasizes background noise reduction. In this way, the conversation scene is organized into multiple sound streams which can be processed differently.

Supplemental Technology: What is it? When to recommend it?

The efficacy of Signia’s multi-stream technology has been documented in the laboratory (Jensen, et al 2023) and in real world listening (Folkeard, et al., 2024). Given the novel nature of multi-stream technology, and the evidence supporting its effectiveness in real world listening, it is well-suited for providing optimal performance in all conversational settings. For some wearers, however, hearing aids alone –even those with multi-stream technology-- might fall short of expectations. It is the responsibility of the audiologist, working in a holistic, person-centered manner, to identify the linguistic, auditory, and visual complexities individuals with hearing loss might encounter during conversations and discuss potential supplemental technologies that enhance the performance of their hearing aids. A topic we discuss next.

Thanks to the popularity of smartphones and apps, many hearing aid wearers have access to a range of low cost, easy to use technologies that supplement the noise reduction features on their hearing aids. There are three types of supplemental technologies that when used with hearing aids might provide added benefit in group conversational situations, especially those with noisy or reverberant backgrounds.

Crowdsourcing Apps. These apps combine an accurate and calibrated smart phone decibel meter with GPS and crowdsourcing features that enable app users to rate the loud level of various locations in their location. One example of this SoundPrint, a mobile app designed to help people find quiet places such as cafes, bars, restaurants and other public places based on their ambient noise levels. The app relies on crowdsourcing and GPS to profile venues in the user’s area and noise levels are categorized into different noise levels (moderate, loud and very loud).

Live Voice to Text Apps. There are dozens of apps the convert spoken word into written text in real-time. These apps use speech recognition technology to transcribe audio input instantly, essentially turning a smartphone into a portable closed captioning system. Many of these apps charge a monthly subscription, but some are free. Apple Dictation, Google Voice Typing, Otter.ai, Dragon Everywhere and Evernote are some of the live voice to text apps available for smartphone users.

Remote microphones. Available for decades, remote microphones place the microphone input much closer to the talkers of interest. Today, Bluetooth-enabled remote microphones are easier to use and cost less than their antiquated FM-based cousins. These systems improve the SNR 12 to 18 dB compared to hearing aids with omni-directional microphones (Lewis et al., 2004).

Even though these technologies are readily available, the role of the audiologist is to identify patients who are most likely to benefit from them. Included in this role is the audiologist’s ability to account for the hearing aid wearer’s digital literacy, which includes the wearers competence and skill navigating use of a smartphone and apps. This begs the question, who are good candidates to use these supplemental technologies? Taken together, it is often time consuming to both the patient and the clinician to discuss and incorporate digital technologies into the fitting process, and there is often an added monetary expense associated with using them. As noted previously, there is ample evidence suggesting that the signal to noise ratio (SNR) in loud listening environments (e.g., 75 dB SPL) is an adverse -5dB. There is also evidence indicating that these adverse SNR listening situations are popular places where people commonly socialize (Bottalico, et al 2022). Although all hearing aid wearers would probably benefit from supplemental technologies in these adverse SNR situations where conversations commonly occur, adults with a significant problem understanding speech in background as objectively measured on the Quick SIN, or as measured on a validated self-report would be strong candidates for these supplemental technologies. Recently, Fitzgerald et al (2024) found the high frequency pure tone average (HFPTA) from an individual’s audiogram combined with QuickSIN SNR loss are predictive of self-reported auditory disability as measured on the five questions devoted to speech understanding on the Speech Spatial Questionnaire (the so-called SSQ12-Speech5) (Noble et al 2013). They calculated that a HFPTA of >40dB HL and a Quick SIN SNR loss of equal to or larger than 7dB correctly predicted 92% of the “poor” scores on SSQ12-Speech5. (They used a score on the SSQ12-Speech5 of 6.83, which is 2 standard deviations below the mean score for a group of normal hearing older adults, as a cutoff for “good” vs. “poor”). In contrast, according to their analysis, the relatively poor specificity of these two measures (Quick SIN and HFPTA) suggests there are many individuals with near-normal pure tone thresholds and/or normal speech understanding in noise ability who could be missed, and presumably deprived of optimal intervention, without first measuring their self-reported auditory disability.

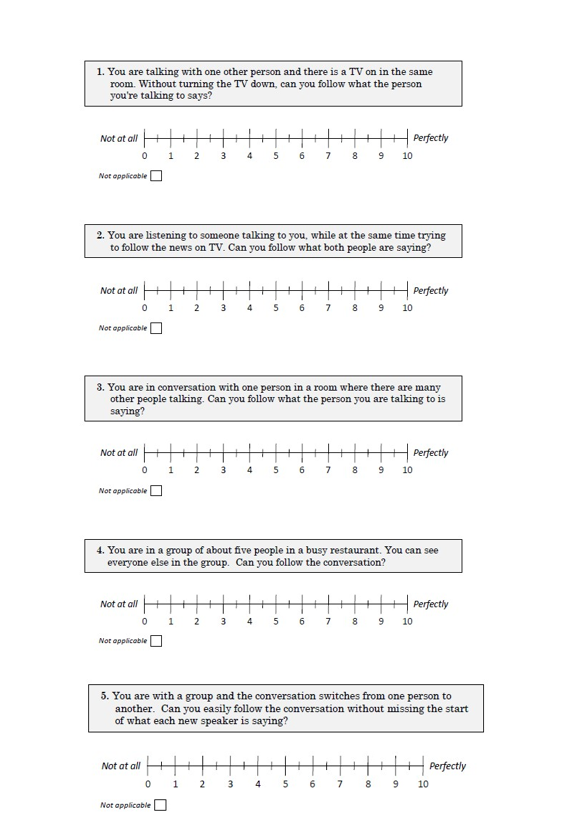

In practical terms, a short, validated self-report like the SSQ12-Speech5 score could be used to determine who might be a good candidate for these supplemental technologies. Considering that understanding speech in the presence of noise is often an essential part of participating in conversations, we believe the SSQ12-Speech5 is a handy and fast way to quantify self-reported difficulties in these situations. Applying Fitzgerald et al’s (2024) analysis, clinicians could administer these five questions during a pre-fitting appointment and then simply take the score for each of the questions on the 0 to 10 scale, add them and divide by 5. If that averaged score is less than 6.83, that is a good indication of “poor” self-reported auditory disability. The SSQ12-Speech5 is shown in Figure 4.

Even the most sophisticated noise reduction schemes on board a modern hearing aid may fall short of expectations for any patient, but this is likely to be especially apparent to those who fall into the “poor” category on the SSQ12-Speech5. As a result, recommending the use of supplemental technologies such as the three listed above that improve the SNR of the listening situation or augment the patient’s ability to participate in conversations in these high noise settings, should be considered for patients with a “poor” score on the SSQ12-Speech5, or those with a SNR loss on the Quick SIN of equal to or larger than 7dB in combination with a HFPTA of >40dB HL.

Figure 4. The SSQ12-Speech5 (Fitzgerald et al 2024).

Shape Listening Experiences in a Positive Way

A final clinical tactic that could be used to help patients obtain improved outcomes in conversational situations is related to how clinicians shape the patient’s initial experiences with hearing aids. As many experienced audiologists know, it is common for patients to focus considerable attention on many of the negative experiences associated with initial use of hearing aids. In our experience, this is especially apparent in situations where there is significant amount of background noise, such as social situations or group conversations. Recall that negativity bias refers to the tendency of individuals to give more weight to negative experiences than positive ones, and these challenging listening situations are often a likely place where it arises. This phenomenon can impact hearing aid wearers, as they might focus more on any negative experiences, thereby ignoring the benefits of their hearing aids.

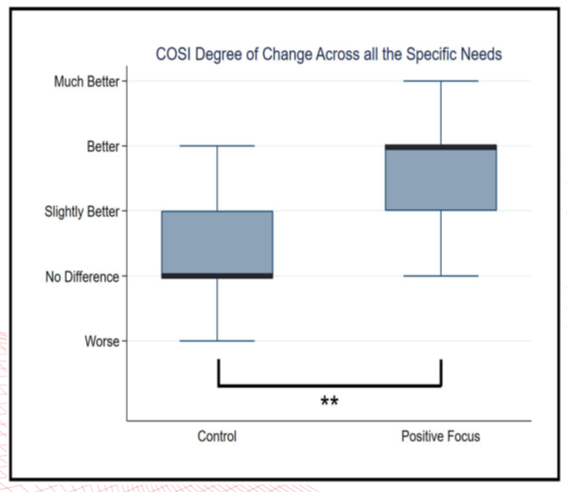

Lelic et al (2024a) investigated whether focusing on positive listening experiences could enhance the speech-in-noise abilities of experienced hearing aid users. Thirty participants were divided into two groups: a control group and a positive focus group. Both groups were fitted with the same brand and model of hearing aids by the same audiologist. At the time of the fitting, the Client-Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) was conducted. All participants were then asked to use their new hearing aids for three weeks and send a daily text message to the audiologist reporting the number of hours they used the hearing aid that day. In addition, only the participants in the ‘positive focus’ group were asked to focus on and report their positive listening experiences in that same text message. At the end of three weeks of hearing aids use, all participants completed the COSI again. The results, as illustrated in Figure 5, show that the positive focus group received, on average, about two categories more improvement as measured on the COSI. In a related study, the beneficial effects documented in the ‘positive focus’ group persisted 6 months after the study ended (Lelic, et al 2024b). These results suggest asking patients to focus and reflect on positive listening experiences after the initial fitting yields better outcomes. In practice, audiologists could encourage patients to keep a written log of all their positive listening experiences – places where hearing aids are making a positive difference. The log with the positive experiences can be reviewed during follow-up appointments. In similar fashion, audiologists could obtain the permission of patients to send periodic text messages, reminding patients to log their positive listening experiences in real time. Rather than manually texting patients who opt into this service, audiologists could rely on an automated texting service that is HIPAA compliant. (See, for example, Textline). We believe shaping positive listening experiences in this way is a useful tactic that can be used with all patients, but it could be especially beneficial for listening situations that rouse a large number of negativities such as noisy or reverberant places where many crucial conversations tend to occur.

Figure 5. Results on the COSI for two groups of hearing aid wearers. From Lelic et al (2023).

Summary

Several longitudinal studies indicate the secret of a long, happy life is the ability to develop and maintain quality relationships. Of course, the kernel of virtually all human connections is the ability to spontaneously, willingly, improvisationally communicate with others. After all, the ability to converse in this manner is a skill all human beings are born with. As recent research demonstrates, successful communication involves the accurate exchange of information between people, and persons with hearing loss as well as their communication partners lose this innate ability. Audiologists are instrumental in optimizing outcomes in these conversational situations, which are often some of the most important places people communicate. In addition to recommending hearing aids engineered for optimal performance in conversational settings (Signia IX), three other clinical tactics are outlined in this article that audiologists can leverage to improve patient performance in conversational situations. Don’t all hearing aid wearers deserve to hear their best in the places that matter the most to them?

References

Beechey, T., Buchholz, J. M., & Keidser, G. (2020). Hearing Aid Amplification Reduces Communication Effort of People with Hearing Impairment and Their Conversation Partners. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 63(4), 1299–1311.

Bott, A., & Saunders, G. (2021). A scoping review of studies investigating hearing loss, social isolation and/or loneliness in adults. International Journal of Audiology, 60(sup2), 30–46.

Bottalico, P., Piper, R. N., & Legner, B. (2022). Lombard effect, intelligibility, ambient noise, and willingness to spend time and money in a restaurant amongst older adults. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 6549.

Danermark, B. (2014) (Re)Capturing the Conversation: A Book About Hearing Loss and Communication. Kanishka Publishers: New Delhi.

Dillon, H., James, A. , & Ginis, J. (1997). Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 8(1), 27–43.

Fitzgerald, M. B., Ward, K. M., Gianakas, S. P., Smith, M. L., Blevins, N. H., & Swanson, A. P. (2024). Speech-in-Noise Assessment in the Routine Audiologic Test Battery: Relationship to Perceived Auditory Disability. Ear and Hearing, 45(4), 816–826.

Folkeard, P., Jensen, N. S., Parsi, H. K., Bilert, S., & Scollie, S. (2024). Hearing at the Mall: Multibeam Processing Technology Improves Hearing Group Conversations in a Real-World Food Court Environment. American Journal of Audiology, 1–11. Advance online publication.

Holman, J. A., Ali, Y. H. K., & Naylor, G. (2023). A qualitative investigation of the hearing and hearing-aid related emotional states experienced by adults with hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology, 62(10), 973–982.

Hornsby, B. W. Y., Camarata, S., Cho, S. J., Davis, H., McGarrigle, R., & Bess, F. H. (2023). Development and Validation of a Brief Version of the Vanderbilt Fatigue Scale for Adults: The VFS-A-10. Ear and Hearing, 44(5), 1251–1261.

Huang, A. R., Reed, N. S., Deal, J. A., Arnold, M., Burgard, S., Chisolm, T., Couper, D., Glynn, N. W., Gmelin, T., Goman, A. M., Gravens-Mueller, L., Hayden, K. M., Mitchell, C., Pankow, J. S., Pike, J. R., Sanchez, V., Schrack, J. A., Coresh, J., Lin, F. R., & ACHIEVE Collaborative Research Group (2024). Loneliness and Social Network Characteristics Among Older Adults with Hearing Loss in the ACHIEVE Study. The Journals of Gerontology, 79(2).

Jensen, N. S., Smara, B., Parsi, H., Bilert, S., & Taylor, B. (2023). Signia white paper: Power the conversation with Signia Integrated Xperience. Signia Pro. https://www.signia-pro.com/ en/blog/global/2023-09-power-the-conversation-with-signia-integrated-xperience

Lelic, D., Parker, D., Herrlin, P., Wolters, F., & Smeds, K. (2024a). Focusing on positive listening experiences improves hearing aid outcomes in experienced hearing aid users. International Aournal of Audiology, 63(6), 420–430.

Lelic, D., Herrlin, P., Wolters, F., Nielsen, L. L. A., Tuncer, C., & Smeds, K. (2024b). Focusing on positive listening experiences improves hearing aid outcomes in first-time hearing aid users: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Audiology, 1–11. Advance online publication.

Lewis, M. S., Crandell, C. C., Valente, M., & Horn, J. E. (2004). Speech perception in noise: directional microphones versus frequency modulation (FM) systems. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 15(6), 426–439.

Nicoras, R., Gotowiec, S., Hadley, L. V., Smeds, K., & Naylor, G. (2023). Conversation success in one-to-one and group conversation: a group concept mapping study of adults with normal and impaired hearing. International Journal of Audiology, 62(9), 868–876.

Noble W., Jensen N.S., Naylor G., Bhullar N. & Akeroyd M.A. 2013. A short form of the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing scale suitable for clinical use: the SSQ12. International Journal of Audiology, 52(6), 409-412.

Palmer, C. V., & Mormer, E. (1999). Goals and expectations of the hearing aid fitting. Trends in Amplification, 4(2), 61–71.

Petersen, E. B., MacDonald, E. N., & Josefine Munch Sørensen, A. (2022). The Effects of Hearing-Aid Amplification and Noise on Conversational Dynamics Between Normal-Hearing and Hearing-Impaired Talkers. Trends in Hearing, 26, 23312165221103340.

Petersen E. B. (2024). Investigating conversational dynamics in triads: Effects of noise, hearing impairment, and hearing aids. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1289637.

Shukla, A., Harper, M., Pedersen, E., Goman, A., Suen, J. J., Price, C., Applebaum, J., Hoyer, M., Lin, F. R., & Reed, N. S. (2020). Hearing Loss, Loneliness, and Social Isolation: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngology--Nead and Neck Surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 162(5), 622–633.

Citation

Taylor, B. & Jensen, N. (2024). (Re)Connecting to the conversation: how and why to optimize outcomes in group communication situations. AudiologyOnline, Article 29164. www.audiologyonline.com