This is a transcript of a live expert seminar on AudiologyOnline. Please donwload supplemental course materials.

Greetings to everyone from Minneapolis, Minnesota. We are going to talk about quality today. Because of my background as a clinical audiologist, I know that there is a whirlwind of activity inside your clinics every day between trying to take care of patients and managing the practice. So my goal is to try to make the information as practical and as actionable as possible.

Before we start doing that, I thought it would be kind of fun to play a brand association game. I am going to discuss four different brands and talk about what some of these brands might be known for. As consumers, I am guessing that most of us purchase these things every single day. I think the people who come to our offices for services need to be treated as patients and also as customers. That is something that all of us need to appreciate every single day.

To make this connection, I thought we would start by talking about four very well-known brands. The first is Heinz Ketchup. It has been around for a long period of time. Some of us might remember Carly Simon, who was used in the commercials back in the 1970s. Some of you also may know that the bottle is designed to make the ketchup come out faster if you tap on that little engraved 57 on the glass bottle. We also know that it has been the leading brand of ketchup for maybe over 100 years. There is a reason for that, which we will talk about in a little while. People pay more for Heinz Ketchup than they do for the generic equivalent.

The next brand that I want to mention is the luxury car brand Lexus. Lexus has only been around for 20 years. It is a division of Toyota. The interesting thing about Lexus is that it was developed from the ground up by Toyota because they recognized there was an opportunity for them to go into the luxury car market. So they did quite a bit of research and went into the luxury car market.

The next brand that some of you might recognize is Nordstrom. Nordstrom is a well-known department store that carries a broad line of clothing and other apparel. Nordstrom, more famously, is known for outrageous levels of customer service. Several years ago, a man in Alaska tried to return tires to the Nordstrom store, not knowing that he could not purchase tires there. Because his family members were loyal shoppers of Nordstrom, they gave him store credit for the tires anyway. Now, that is probably something that you would not want to do in clinical practice, but it is an interesting story that showcases the legendary level of customer service that Nordstrom aspires to.

Finally, we have the medical organization Mayo Clinic. They are known for their collaborative approach to the delivery of high-quality medical care. There are only three Mayo Clinics in the entire world. One is in Rochester, Minnesota, one in Jacksonville, Florida and one in Arizona. Mayo Clinic has an interesting story because it was started by a couple of brothers over 100 years ago, and their brand of medicine became very popular due to its collaborative approach and focus on research and teaching. I think there are some lessons that can be learned from that brand as well.

The question you might want to ask yourself is, “What do these four brands have in common?” We are talking about ketchup, cars, apparel, and medical care. If you are a student of business, you might notice that those four businesses or brands started from the ground up. These were usually small, mom-and-pop types of organizations that expected significant organic growth over time. In other words, they were not built and did not grow through acquisitions. They grew organically.

We also know that all four of those brands are very profitable and they have been for quite some time. We also know if you go to the American Customer Satisfaction Index (https://www.theacsi.org), you will find that quarter over quarter or year over year, those four brands have some of the highest, if not the highest, customer satisfaction scores for their respective brands. For the average consumer not immersed in the business models, which I think is the vast majority of us, we know these are nationally-recognized household names. Even if there is not a Mayo Clinic in your region, you know what that brand stands for.

You also know that all those brands, for the most part, are best in class, and they deliver exceedingly high levels of customer satisfaction. The lesson to be learned here by looking at these four different brands and is that they all stand for quality. I hope to paint the picture that when a brand is known for quality, people will seek it out, and they are often very willing to pay a little bit extra for the high level of quality. So how do we get there? That is what we are going to look at today.

I have tried to split this up into two parts. In part one, I want to talk about quality as a concept, the why’s and the how’s behind quality, and how it can be a driver of your success in clinical practice. There are many lessons we can learn from our friends on the manufacturing side of things. In part two, I want to talk about some actionable tactics that you can use clinically. I call this reality-based practice. The bottom line is that I hope you can appreciate the importance of quality.

Quality

There are three major concepts that are woven throughout the concept of quality. Quality, which is somewhat difficult to define, is process oriented, data driven and patient centered. Quality is process oriented, meaning that you are developing standards and mapping out processes and protocols in your clinic with respect to patients, and that is important. Quality is data driven, which means that when we identify a problem and we strive to improve it, we use data to support our tactics and our procedures. Finally, it is patient centered, which means that everything we do reflects the voice of the patient or the customer. These three models become a mindset that becomes an inherent part of your culture.

Quality is an abstract concept to define. Let’s look at it from another point of view. To get a good feel of what quality is, I would like to use the example of a recent visit to a deli I had with my friend. I think all of us like food. My friend happens to like food in very large quantities, but he also likes high-quality food. Let’s talk about how each of us would define a high-quality meal.

We all have a slightly different definition of what a high-quality meal might be. There are many choices when it comes to how we want to spend our money at restaurants and on meals, but do we ask ourselves, “Is that a place that I want to patron again and again?” One thing we might look at is the setting. When we walk into the restaurant while we are waiting to be seated, is it clean? Is it warm? Does it feel like a place where you want to spend some time? Is the seating adequate and comfortable for both small families and large groups of people? How is the quality of the service? Did they take my order promptly? Is it easy to read the menu? Do they answer my questions? Do they have a wide range of prices? When the food is plated and brought out to me, does it look appealing? Does it look like something I want to take a picture of and send out to my friends on Facebook, or is it something that I am not too excited about? Those are some things we look at. The food itself is also part of the equation, obviously. Is the food tasty? Do my children like it? Does my friend like it? Finally, what is the experience like when I have to pay? Do I have to wait a half an hour to get the check or do they bring it to me right away? Can I use a credit card?

We have ways to voice our opinion today unlike any other time in history. I call this the “Yelp Effect.” The bottom line is that someone is always looking over your shoulder to judge and evaluate your business. If you doubt that, type in your favorite doctor’s name into a search engine, and usually you are not directed to their Web site, but rather to a Web site that does physician reviews or audiology reviews. The voice of a customer is very easy to get out there, thanks to the Web.

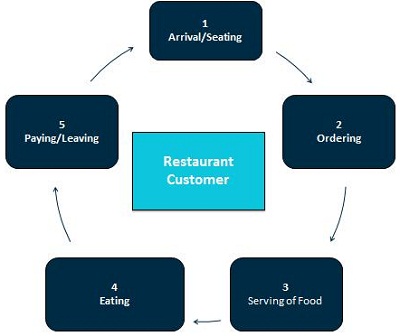

The following is a review that I am hoping you do not see about your clinic. Some of you may know that Lady Gaga’s parents recently opened an Italian Restaurant in New York City. There was a negative review stating that it was worse than herpes. My point is that someone is always looking over your shoulder and evaluating that entire experience through your business. Even though the quality of the food might be pretty good, other components of that experience might make it a rather negative one for the patient or the customer. A big part of quality, as I mentioned before, is being process oriented. Probably the first lesson about being process oriented is your ability to segment the customer journey through your business. Figure 1 is a flow chart of how I might I might segment the customer’s journey through my restaurant if I were a restaurant owner.

Figure 1. Cycle of a restaurant customer’s experience from beginning to end.

I am going to use this as an example before we start talking about how this would apply to a hearing aid or an audiology practice. The restaurant owner should want to pay close attention to detail and have a process for the arrival and the seating. They should have a process and sequence of events under ordering, which is number two. Number three is serving the food. Number four is finally getting to enjoy the food, which is a result of whatever that chef is preparing in the back. Finally, we have the exchange of paying and leaving. I think there are some important lessons that can be learned from the restaurant example, because it shows you that the center piece of most restaurants is the quality of the food.

However, there are a lot of other items and tasks that have to be done properly in order for that even to happen and for the patients to experience quality. If you look at how restaurants exude quality, I would say there are probably six important substeps to that process. The first one is to create culture around your business. What do you want your restaurant to be known for? Do you want it to be known for a certain type of food or for the most expensive, highest-quality food? Regardless of what you want it to be known for, you need to have that part as the centerpiece when you are creating the culture.

The second major component that drives quality is the orchestration of the staff and clearly defining what each member of your staff does in your business. They each play a specific role, and drilling down to the detail of how they would execute each part of that role is important. The next component is following standards. For the chef, it could be following the recipe. After all, that chef is probably not going to be there every single night to prepare it. That recipe has to be written down and replicated by several people.

Consistency around serving the food, cleaning up, taking the order, all of those can be standardized. And then it is one thing to create and follow standards, but then who is there to inspect those standards to make sure they are actually being implemented and executed by the staff. And then finally, you are going to listen to feedback from the customer. That is where Yelp or a comment card comes in handy, and that is going to help you determine where you need to improve and what is important to the customer. Finally, it becomes more or less a feedback loop where you are always updating and improving standards and the orchestration of the staff as needed based on the feedback or data that you collect from the customer.

Believe it or not, the way a hearing aid manufacturer operates on a day-to-day basis is very similar to how a restaurant operates. We see six very similar principles to driving quality within the hearing aid realm. First is creating a culture around which your office is going to operate. Hire well and orchestrate the staff, knowing that each person of the process is going to play a specific role. These staff must follow standards within a culture of consistency. Often times, those standards are external, but they help create consistency and drive out error. Of course, along with that is the inspection of the standards and listening to feedback from customers, which, in the case of a hearing aid manufacturer would be the audiologist or the hearing instrument specialist. Finally, using that data that they collect from the consumer, which is you and also the patient sometimes, they are going to use that information to find out where they need to update and improve their manufacturing process. The interesting thing to note is that just about any business that makes a widget, a device or an item of food follows the same general process to create consistency and to create quality.

You might be asking yourself, how does a manufacturer do that? What is their plan when it comes to carrying out these six items in their manufacturing facilities? There are actually some different schools of thought that many manufacturers use in general, not just in the hearing aid industry. Any company, from those that manufacture medical devices to automobiles, use quality control measures and some of these things are listed here.

We could go on for hours talking about lessons from manufacturers and business strategies like Six Sigma, DMAIC, lean production, Perato, which is the 80/20 rule, and Total Quality Management. These are ways of learning how to implement quality standards in the manufacturing process. They are a school of thought and some are even a certification process. My point here is to show you this is a studied way of bringing quality into the manufacturing of any device.

For example, one very common project management methodology under Six Sigma is DMAIC, an acronym that stands for Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control. My main point in showing you this is because it is very process oriented and it gets into a very granular level of detail when it comes to driving quality in the manufacturing process. These concepts like Six Sigma or Total Quality Management are trying to drive out the variance in the manufacturing process through a series of implementation of standards, inspection of standards, collecting data, and by looking for areas that will give you the most bang for your buck when you try to improve them. Those are ways to drive out variance.

Six Sigma, in particular, is very statistically driven through the collection of data to find out how much variance there is from the best and try to reduce that variance in a very process-oriented way. Manufactures rely on these processes every day, and they have for decades to try to drive our variance and improve quality. I think there are opportunities to do the same thing in the clinical world. Of course, there is one important difference that we will get at in a minute. An example of one very common standard in hearing aid manufacturers is the ISO 9000, or the International Organization of Standardization. You can think of this as the Good Housekeeping seal of improvement. When you peel away the details and all the analyses, we can learn that the ISO 9000 standardization process creates standards based on best practices. Those standards are created by a panel of experts that understand the field use data to make decisions. The second major component of ISO 9000 is that there is a very elaborate auditing process, which is the standing-over-your-shoulder to evaluate how things are being done.

When an audit occurs, it is an external process where somebody from that panel of experts comes in. But in a very significant part of ISO 9000, there is an internal process where somebody within the organization is responsible for the day-to-day management of quality. The three components of the auditing process would be to tell the board what you are doing, show them what you are doing, and then have the data to prove that what you are doing is contributing to a better quality device or product. These are some concepts that I think we can look at and adapt into our own clinical practices, which we are going to do in part two.

To give you an idea of how this might work for ISO 9000 or for DMAIC in your practice, the easiest thing to look at would be returns for credit, because that is a variation from the norm. That is an inefficient part of our day-to-day process, so how could we use ISO9000 or DMAIC to reduce our return and exchange rate?

First, you would want to define the problem and determine the root cause of it. The Perato effect looks at all of the root causes and then finds the one or two that contribute the most to the variability. That Perato effect would be part of defining the problem and figuring out the one or two things that you need to do to reduce your return rate.

Keeping with the concept of ISO and DMAIC, the next thing you would do is develop a plan for improving it. You might want to go out and identify one or two best practices either in the published literature or maybe from somebody that you know is very successful in this area and try to implement those practices in your own clinic. Along with that, you are going to have to find some way to measure progress. You are going to have to periodically review the measurement tool; you are going to be looking to see if it made a difference, and further to look for ways to continuously improve. By now, I am hoping that you are realizing that quality is very process oriented, and it needs to be imbedded in your culture. It is not a one-time thing that you do. It is a way of life within an organization, where everyone is striving to improve quality by using processes and data to get there.

So, before we get into part two of our presentation today, I thought it would be a good idea to go into a bit more detail about why quality even matters. If there is not a quality issue within our profession, then why bother to start implementing some of these concepts that I am talking about? The big-picture reason why quality matters for any business is that most of us know firsthand that failures, especially those that happen over and over again, are the recipe to destroy a business.

Negative word of mouth gets out very quickly. People magnify the effect on social media forums or Web sites like Yelp. That can truly destroy a business if you have a consistent failure rate. One easy failure rate for us would be returns, but as we will learn, there are many more. Beyond that, management of quality improves any business. If you think back to Heinz, Mayo Clinic, Nordstrom and Lexus, the management of quality in any of those businesses is what makes them number one or best in class for their respective category. That trickles down to the staff, to the shareholders, to the vendors and ultimately to customers or patients. There is a cascading effect related to our ability to effectively manage quality in our business.

Defining Quality

Let’s talk about how we would define quality in clinical practice. So far, we have talked about businesses that make a device or produce goods, but what makes health care different, relative to the other brands that I mentioned, is that we are actually working with people. The quality is focused on the way we have solved the patient’s problem, fit the device or treated that person. I think it is important that we step back from all of these brands we talked about in part one and look at some of the differences within an audiology practice and what makes hearing aid dispending even more unique.

Here is a definition of quality care that comes from the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies: care that is safe, effective, efficient, evidence based, equitable, patient centered, and timely. I think most of us would agree with this definition. But what makes audiology and hearing instrument specialists unique is that, for most of us, there is a merging of two different worlds.

On one side, we have the medical part of what we do, which is identifying a medical condition and using a medical device, usually a hearing aid, to treat that. On the other end of things, however, we are, more often than not, asking patients to pay at least part or all of the cost of our service and product out of pocket. We have to think of these folks as customers. There is a medical and a retail component to our business, which is different than a lot of other medical subspecialties. We have these two worlds coming together.

If you were to ask 100 audiologists how to define quality in their own practice, I would say they have a fairly narrow view of quality. This is more of the medical model at work. For them, the quality would be the outcome of the fitting. Are the patients benefiting in the real-world situations where they need it? If the patient kept their hearing aids, that would be, for most of us, a solid definition of quality. But when we add the retail component to it, we have to look through the lens of the patient. A patient-centered view of quality would be much broader.

In addition to the outcome, which is obviously important, customers are evaluating the cleanliness of the office, the friendliness of your staff, your appearance, the appearance of your waiting room, your parking lot, and anything you can think of related to your practice. We have to account for all of these things when we are defining quality in our practices. That being said, do we have a quality problem in audiology? If we are all happy with quality and our patients are getting the level of service that we require, maybe we do not need to focus on any of these concepts for manufacturing or bring them into the clinic. I would say, however, after looking at some data, that we would be mistaken to think that.

Here is some data. The first one comes from the Blue Mountain Study that was published a couple years ago (Hartley, Rochtchina, Newall, Golding & Mitchell, 2010). Twenty-four percent of hearing aid owners in their study never wore their hearing aids after they purchased them. Sergei Kochkin has done a tremendous amount of work over the last few decades, and in one of the more recently published papers, (2011) he mentioned that one-third of fittings result in a failure. The definition of a failure would be that the patient returned the hearing aid for credit or when the patient does not wear their hearing aid at all or they only wear it a few hours a day when they absolutely have to have it.

We also know that if established best practices contributed to a higher-quality fitting, we could use those opportunities for improvement as well. We know from survey data (Mueller & Picou, 2010) that only about one-third of professionals use probe microphone measures to verify the fitting target, and only about 36 percent validate the fitting with some type of self-report or questionnaire (Humes & Krull, 2012). Those are two examples of best practices that have been mentioned in the literature many times as contributory to a better quality fit, yet only one-third of clinicians out there are actually using those procedures.

Data from the MarkeTrak studies last year (Kochkin, 2011) indicate that clinicians that use both verification and validation run a more efficient practice. The average patient comes in 1.2 times less over the year, compared to other patients for clinicians who do both verification and validation. Another study published a couple years ago from the MarkeTrak group (Kochkin, et al., 2010) showed that the things we do during the prefitting, the protocols that we use and so forth, contribute to a more successful fitting. The authors converted it to a success score, and found that if the success score was between 7 and 10, it was more likely to be achieved by clinicians that completed six or more items of a clinical protocol.

Part Two: Systematizing Quality in Your Clinic

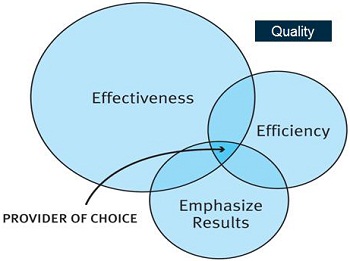

I want to take all of the concepts that we talked about in the part one and talk about how we can bring some of those to life in your clinic. I will call this the systematizing of quality in your clinic. So how do you take all this information and create a system in your clinic? One of the things I want clinicians to be thinking about when they are trying to systemize quality is that there are probably three buckets you have to be thinking about in clinical practice, which are represented in Figure 2. You see effectiveness, efficiency, and an emphasis on results.

Figure 2. The three E’s of quality: effectiveness, efficiency and emphasize results. The overlap of all three qualities represents a provider of choice.

I think that when all three of these things are implemented in a clinic, you can become the provider of choice. This is when people flock to your door trying to seek you out. Let’s expand on these three E’s: effectiveness, efficiency, and emphasize results. Effectiveness is your ability to use evidence-based practice in the decision making process. That is a whole topic unto itself that we will not get into today, but that is the first E. The second E is efficiency, which is really the optimum time that you spend with the patient. This includes work flow in your office. How do we maximize patient satisfaction around that? The third E is an emphasis on results, which is your ability to measure, either directly or indirectly, if what you did made a difference to the patient or contributed to a more successful fitting. It is really only through measurement that we can compare results across clinics and across practitioners. It is only through measuring that we can actually improve things, because if we do not measure it, we really do not know what is going on. If there is any one lesson you can take from this presentation today it is this: find one thing in your clinic that might contribute to a better quality outcome and begin measuring it. We know that many practitioners do not measure much of anything, but those three E’s form the center of what I call reality-based practice.

Reality-Based Practice

There are five things I want you to know about reality-based practice. First of all, next to an automobile, hearing aids are probably the most expensive item that many of our patients over the age of 70 will purchase. We also have to respect the fact that patients have a choice in how they spend their money. Instead of going on that cruise or having cosmetic surgery, we want them to pursue amplification if they need it. Number three is the shared decision-making process and this other concept called the progression of economic value form the core of how you differentiate your practice on quality lines. I have already mentioned number four, and that is that someone is always looking over our shoulders to judge and evaluate our practice. It is either going to be a review board, a panel of experts from an insurance company, or patients on a face-to-face basis. More and more patients go to a Web site and critique your work. We have to acknowledge that fact. Number five is the identification and implementation of data-driven best practices in our clinics on a daily basis.

I mentioned before that most of us live in a medical and retail arena, and we have to respect that fact. Let’s talk about some ways that we can better serve our patients and how our patients make decisions.

The patient comes into your office and they know they are getting a medical service of some kind. You ask yourself, “How can I possibly help them make a decision?” There is some interesting research and thoughts on this process (Charles, Gafni, & Whelan, 1997). In the medical arena, there is a kind of decision-making continuum. On the far left you have the paternalistic way of making a decision where the doctor pretty much tells the patient what to do, and the patient plays a very passive role. Perhaps that works very well when the patient has an acute problem. On the far right of the continuum, you have an informed decision where the professional, more or less, is giving the patient information and then the patient is making the decision independent of the professionals’ guidance. In other words, we give the information, whether that comes from a personal visit, a Web site, or even a call center, and the patient makes a decision. This direct-to-consumer model, which I think most of us know, is not very good for our profession.

Somewhere in the middle lies this sweet spot for audiology, and that is a shared decision-making model, which is where the patient and the professional work together to solve a long-term condition. We look to not only collaborate on the options, but also collaborate on the goals and the results. The reason I bring this up is that the shared decision-making model lends itself well to improving quality in the clinic because the patient has to work with the provider not only on the establishment of goals, but also on the results. When we are trying to measure results, the shared decision-making model is known to be the current best practice when it comes to delivering healthcare for chronic, long-term conditions such as adult-onset hearing loss.

In the shared decision-making process, there are four important questions that you have to ask the patient (Laplante-Levesque, Hickson, & Worrall, 2010). First of all, the patient must decide, “Am I going to obtain hearing aids today or am I going to do nothing?” The four questions that you advise them on would be, “What is involved in the process? What is expected of me? What are the positives? What are the negatives?” One of the best practices around improving quality that I want to present is the shared decision-making process in those four questions.

On the other side of that, we do have acknowledge the importance of the retail aspect of what we do because it is serving customers. I want to talk about this economic concept called the progression of economic value. This tells us that in a commodity-driven business, the way to create value and make yourself unique is to deliver a service and to provide an experience. Perhaps the simplest example of this is coffee. If you were to buy coffee 150 years ago, you would have to go to the local mercantile and buy a 30 or 50 pound sack of coffee. You might have to roast and grind that coffee yourself; it is a very labor-intensive operation. Companies 75 or 100 years ago, however, decided to grind and roast the coffee and place it in a can or a bag, and people would go to the store and purchase that coffee at a higher price tag, but they knew customers would do that because it was more convenient. Then restaurants got the idea that they could deliver a cup of coffee, maybe a bottomless cup of coffee, for a few dollars during breakfast. The coffee might have been a little bit mediocre, but it was convenient and easy to get, so that small upcharge was worthwhile. Finally, Starbucks, among others, got the idea of wrapping an Italian café experience around that coffee that costs pennies on the dollar, charging five or six dollars for a latte, because they are able to wrap a remarkable, memorable experience around it.

So when it comes to driving quality in your office, one of the fundamentals is to appreciate and acknowledge this progression of economic value. After all, these days, commodities like hearing aids can be purchased online. But when you wrap a clinical experience around it, you can add more value. If you want to add even more value, wrap a memorable experience around that clinical procedure. In many ways, the progression of economic value forms the underpinnings of a quality movement within your practice.

How do we use that model to drive quality and the systematizing of quality? The two things I want to talk about in relation to that model are theming your practice and best-practice implementation.

Theming your Practice

The first is theming your practice. Disney actually did a great job of putting this on the map 50 years ago, because when you think about the Disney parks, they are nothing more than amusement parks. But when you wrap a theme of cartoon characters around it, it makes it much more memorable for the average consumer. So why would you even want to be theming your office? From a quality standpoint, themes are important because they help center your culture within your organization. Even if it is a very small practice, having a theme is a way to get your culture on the map. Themes really resonate with patients.

Figure 3 is a picture of a waiting room at a large medical facility. This serves of an example of a very low bar. For most of us, this is probably what our expectation is when we go to the doctor’s office. Hopefully it is going to be a clean waiting room, but it is not very interesting or engaging.

Figure 3. Standard waiting room of a large medical practice.

When it comes to receiving audiology care, Figure 4 illustrates a pretty standard theme. It is sterile with all the necessary equipment, but from the patient’s point of view, it is not too interesting.

Figure 4. Basic audiology suite with seating and equipment.

I want to show you one more example from the Eye Clinic of Wisconsin (Figure 5). Dr. Heather Totman is there. Believe it or not, they have an audiologist on staff. They do a great job in this clinic of theming the practice around professionalism. When you walk in, they have a very modern motif (Figure 6). They have hardwood floors. They do a great job of using memorabilia to draw the patient in. They have some nice three-dimensional boxes with hearing aids and eye glasses in them hung on the walls of the hallway to the patient suites (Figure 7). They happen to be interesting conversation pieces. Each room has a modern feel. Rather than use a test booth, Dr. Totman has a PC audiometer in a sound treated room (Figure 8). You can see there is a lot of potential around theming, and the reason why theming is important from a quality standpoint is that it is a way to center your culture.

Figure 5. Eye Clinic of Wisconsin

Figure 6. Reception entrance inside the clinic.

Figure 7. Hallway to patient suites with artwork and memorabilia hung on the walls.

Figure 8. Audiology testing room, with PC audiometer.

When you create your own theme, there are five things that I think you pay attention to. First, it has to be professional. You want to exude high-quality, evidence-based practice, but at the same time you want to try to find a way to make it fun and positive. It has to resonate with patients. You want to make sure that it is something that you and your staff are fairly passionate about. Lastly, when you theme, make sure you involve the five senses.

Do not be afraid to use music, visuals or the sense of touch to bring your theme to life. When it comes to theming or segmenting the experience, think back to that restaurant journey. There were five distinct stages (Figure 1). In an audiology practice, I would say we have six distinct stages of the patient journey (Figure 9). We have the promotion, or the way the patient became aware of your practice. We have the phone scheduling, which is how the patient likely made an appointment with you or had some questions answered before they saw you. Then we have the actual arrival and then the testing and recommendations, which are the equivalent of eating the food. That is finally when you get to practice your specialty. That runs through the next step, which is fitting and purchase, and then finally, follow-up.

Another lesson around quality would be to segment the patient journey through your practice along these six stations (Figure 9) and then develop and orchestrate some very detailed processes around each one of these stations.

Figure 9. Six-step schematic to the patient experience.

I am going to talk a little bit about some work that comes from an outstanding book called The Experience Economy by Pine and Gilmore (1998). They talk a lot about this 3-S model: provide patient satisfaction, reduce patient sacrifice, and create patient surprise. Once you have segmented the patient journey along those six stations (Figure 9), my challenge to you is to apply this 3-S model to each one of those six individual interaction stations.

Another fun exercise that you can do with your staff is called an experience audit. Imagine that Walter Cronkite is across the street from your practice and he is interviewing every patient that comes out of your office. (For anyone under the age of 40, you may not know who Walter Cronkite is, but he was a very famous television anchorman until about 1982 or so.) He is asking patients to tell him what it was like inside of your practice.

The answer to that question is really the way to develop your own theme or what you want to be known for. The exercise is to ask yourself what you want your patients to say. Write down three to five things you would hope they would say. Then for each of the six interaction stations (Figure 9), write down the positive cues that you want your staff to orchestrate that would lead to a high-quality fitting. You want to try to eliminate all the negative cues that exist today. A good example of that is back in Figure 4, with the trashcan by the audiometer. That is a simple negative cue that you want to try to eliminate.

I wanted to go into more detail with what happens at interaction station number five, which is the fitting and purchase. My intent here is to take some of the concepts that we talked about in part one and apply them to that interaction station. I have a case study that I will share with you to illustrate that area and how you can use best practices in your own clinic. I think it is a four-step process.

It is up to you as the practice manager or as the clinician to, first, identify those practices that lead to the highest outcomes. That is where guidelines from your professional organizations might be helpful, like the American Academy of Audiology. It also could be as simple as networking with other professionals and finding out what has been successful for them. Number two is studying what the most effective offices do. Third, standardize those processes in your own office, and fourth, execute those processes in your clinic with each patient on a daily basis.

Case Study

For the case study, the names have been modified. I will use the hypothetical name of Riverside Audiology Partners, and there are two things we know about this clinic. We know that there are three audiologists, one full time and two part time. Two front office staff that share in the duties. The annual revenue for the practice in 2010 was $450,000. They fit 250 hearing aids, and it was determined that there was a $65,000 loss in revenue as a result of exchanges and returns for credit. We also found out when we dug a little deeper that the average number of appointments for each new fitting was just under five visits. That means that one patient was seen on average 4.8 times over the course of the first year. The other thing to note is that there was really no outcome data at all. We did not know how successful the fittings were based on self-report measures of any kind. Obviously there were many opportunities here to implement quality.

The two most important problems to address are the number of returns and the number of appointments for first-time patients. We know from benchmark data that both those numbers were relatively high (Phonak, 2012a; 2012b). That gave us good first-glance opportunities for improvement. There is a simple step-by-step process to try and improve quality within the fitting and purchase interaction station.

Step number one is setting a goal. Having worked with many practices around the country, I have seen a danger in setting too many goals. Set one goal at a time and work on it until you can move on to the next. That is part of the culture that you can instill.

To determine what the one goal is that you want to work on to improve quality, ask yourself the question: What is the one aspect of the fitting and purchase process you could improve that would have the biggest impact on quality of patient care? So in this case, that would be the $65,000 in returns for credit. In order to get at that question and try to answer it in your own practice, you will likely use some data that was collected in your own practice to help in the decision process. Since this practice was collecting very little data, we will rely instead on published studies or best-practice guidelines to figure out one thing we can do to improve in this area.

With a bit of discussion with the three audiologists, the goal was set to start using probe microphone measures to ensure that hearing aid output was within plus or minus 5 dB of the prescriptive target on 100 percent of the patients that were fitted. The goal to improve quality was simply to standardize the use of probe microphone measures.

Step number two would be the implementation of those standards in our practice. In our case study, this would mean finding ways to ensure that all the audiologists are conducting probe-microphone measures and that they know how to do it accurately. They may have to get some hands-on training. There would need to be some kind of consistency in terms of using the same processes and same targets. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, you need to identify one or two lead measures that will help you monitor changes in performance over time. By definition, a lead measure has to be predictive, which means it is measuring something that contributes to the goal, and it has to be something that is influenceable, or in other words that the person who is actually doing the measure has some influence over it.

In this case, two lead measures would include a protocol check list and a periodic chart review by the manger or lead audiologist to ensure that each patient is fitted within plus or minus 5 dB of the target based on probe-microphone measures. In our case study, this check was done by the lead audiologist on a biweekly basis. The implementation of the standards is about developing the lead measures and making sure that everybody is on the same page and implementing what you expect.

That leads me to step number three, which is monitoring the standards over time. You must look at the new return-rate data and the number of follow-up appointments to see if the return-for-credit rate is actually declining. If it is declining, that means the implemented measures are having an impact and our best practices are actually improving quality. That means it is maybe time to add a new goal.

If you are finding that the return rate or number of appointments is not declining, then you have to start thinking about some other procedure or protocol to evaluate. Step three, monitoring the standards, takes three to six months to get a good idea of your returns and appointment data. This is a long-term process. There are no quick overnight fixes.

Conclusion

To wrap up, we owe it to our patients who are making the most expensive purchase next to a car to make sure that quality is at its very highest, especially when we know they have choice in how they spend their money. From the medical side of things, the shared-decision making process is a way to bring the clinician and patient together from the beginning. This shared decision making and economic value form the core of differentiating our practices. Reality-based practice means that we acknowledge and accept the fact that there will always be someone looking over our shoulder to judge and evaluate our work, and that is usually the patient. That is okay. It is the way the world operates these days, so we must acknowledge it. Finally, we must identify these best practices and find out which ones are going to give the best bang for the buck in your office. Use data in that decision making process. It is imperative to create this continuous-improvement mindset or culture around quality.

I am hopeful that there will be other webinars in the future that get into other aspects of quality. Thank you for joining me today.

References

Charles, C., Gafni, A., & Whelan, T. (1997). Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science & Medicine, 44, 681-692.

Hartley, D., Rochtchina, E., Newall, P., Golding, M., & Mitchell, P. (2010). Use of hearing aids and assistive listening devices in an older Australian population. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 21(10), 642-653.

Humes, L., & Krull, V. (2012). Hearing aids for adults. In L. Wong and L. Hickson (Eds.), Evidence based practice in audiology – evaluating interventions for children and adults with hearing impairment (pp. 61-92).

Kochkin S. (2011). MarkeTrak VIII: Reducing patient visits through verification and validation. Hearing Review. 18(6),10-12.

Kochkin, S., Beck, D. L., Christensen, L. A., Compton-Conley, C., Fligor, B. J., Kricos, P. B., … Turner, R. G. (2010). MarkeTrak VIII: The impact of the hearing healthcare professional on hearing aid user success. Hearing Review, 17(4), 12-34.

Laplante-Levesque, A., Hickson, L., & Worrall, L. (2010). A qualitative study of shared decision making in rehabilitative audiology. Journal of the Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology, 43, 27-43.

Mueller, H.G., & Picou, E. (2010). Survey examines popularity of real-ear probe-microphone measures. Hearing Journal, 63(5), 27-32.

Phonak Marketing Research. (2012a). 2011 Survey of US dispensing practice metrics, part 1. Hearing Review, 19(8), 16 - 23.

Phonak Marketing Research. (2012b). 2011 Survey of US dispensing practice metrics, part 2. Hearing Review Products (Sept), 8 - 13.

Pine, B. J., Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theater and every business is a stage. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.