Editor's note: This is a transcript of an AudiologyOnline live expert seminar. Please download supplemental course materials.

Thank you for viewing this course. This talk is the fourth in a series that I have been doing this year called Hearing Loss from the Inside Out: The Patient's View. This course today is a follow-up to the course Does the Fitting Satisfy the Patient? That course addressed what we know about the patient’s satisfaction with the hearing aid fitting process. One of the things that we know is that patients like to be involved in the process. They are concerned not just about how well their hearing aids work, but also how the hearing aids sound.

In this talk today, I want to focus more specifically on bringing the patient’s evaluation of the sound through the hearing aid into the hearing aid fitting process. When we look at the outcome of a hearing aid fitting, we, as audiologists, have a habit of deciding the criteria of what determines a good or poor hearing aid fitting, but the patient is the one who ends up paying the bill. That is an odd model to me, because we have not historically found very effective ways to consistently and in a structured way bring the patient’s opinion about the hearing aid fitting into the process. We often listen to what the patient has to say, but we typically have not built procedures into our practice to give the patient consistently, and in a structured way, the opportunity to respond to the sound quality of the hearing aids. We should have techniques to better include the patient in the process to have the opportunity to give their opinion about what they are hearing out of the hearing aids.

Subjective Assessment

Subjective assessment of the hearing aid can be done at a variety of times and with a variety of measures. When we normally talk about subjective assessment, it is oftentimes linked to outcome measures such as the COSI (Client Oriented Scale of Improvement), the HHIE (Hearing Handicap Inventory in the Elderly) the APHAB (Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit), or the HAPI (Hearing Aid Performance Inventory). These are subjective assessments of the outcome of the hearing aid fitting. One of the markers of an outcome measure is that it is independent of the process. It is an evaluation of how well that process worked.

This talk is not about subjective assessment as an outcome measure. I want to focus on using subjective assessment during the fitting process, and by using the patient’s opinion about the way sound sounds through hearing aids at the initial fitting. Subjective assessment can be used in a variety of ways throughout the hearing aid process. Outcome measures is one very big area, but today we are going to focus on subjective assessment, specifically as a fitting tool.

One of the things I pointed out in the last course (Does the Fitting Satisfy the Patient? ) was that we, as a field, use a pretty wacky model when it comes to hearing aid fitting. We use a model where we put a lot of emphasis on measuring things about the patient, predicting what should be right for the patient, fitting the patient with products that should meet those predictions, and then we end up doing a lot of fixing of problems after the fact. Anyone who has ever done any amount of hearing aid work knows that there is a tremendous amount of time spent after a fitting with patients, making things right. If we only spent a little bit of time with patients fixing problems, then I think this model would make sense. But the fact that most patients need some sort of follow-up and fine tuning adds to a very strange sort of way of doing our work, where we have so much emphasis on very structured predictive sort of measures, but then we spend a tremendous amount of our time clinically in an unstructured, problem-solving way. That does not feel right.

Part of this idea of bringing more subjective assessment of hearing aid processing into the planned fitting process is to try to get away from this model where we are fixing problems after the fitting and move toward a more proactive approach of solving patients’ issues before they become issues.

A second lesson that came out of the last seminar was that patient satisfaction is driven by more factors than outcome alone. It is not just how well a patient performs with hearing aids that determines whether or not the patient is satisfied with the hearing aid fitting process; there are other factors that come into it. Yes, outcome matters, and, of course, the hearing aids need to work well for the patient and their communication needs. When you talk about patient satisfaction with the fitting process, a tremendous amount is driven by the interpersonal aspect, or the relationship that is built between the clinician and the patient. Patients, now more than ever, have tuned into that interpersonal aspect. They expect to be treated with respect. They expect to be asked their opinions about treatment. It is not the old days of the white-coat approach where the doctor tells you what to do and you just do it. Modern healthcare consumers do not accept that anymore. Building a strong relationship between the patient, seeking out the patient’s opinion, respecting the patient’s opinion and bringing it into the process is a very important part of modern healthcare.

We also know that the care environment impacts a patient’s perception of care. Patients notice whether the parking was good, whether the bathroom was clean and whether the receptionist had a smile on his or her face. All of those things also lead to satisfaction, and they all become part of modern healthcare.

Perception and Reaction

There are multiple influences on sound perception. In other words, when a patient hears sound through hearing aids and reacts to what they hear, that is driven by many different factors. It is not just whether or not we have corrected for the audiogram. One of the things I did not talk about last time, but will go into a more depth now, is that you can broadly categorize the influences on sound perception into how the person perceives sound and then by how they react to that perception. It is not only how their system works, but also what their opinion is about what they hear.

To get more specific, I want to introduce into the discussion something called the Perceptual Filter Model (Bech & Zacharov, 2006). Bech and Zacharov are two sound engineers. One of them works for Bang and Olufsen in Denmark, and the other works for one of the major Scandinavian-based cell phone companies. This concept comes out of their book which talks about perceptual audio evaluation. They talk about the process of evaluating how a person responds to sound. These authors are very intimately involved with it because cell phone companies pay a lot of attention to the way sound sounds through cell phones. The people at Bang and Olufsen care a lot about how sound sounds, as they sell high-end audio equipment.

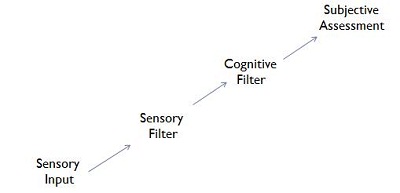

In their book, Bech and Zacharov (2006) talk about what factors go into how a person responds to sound. They describe the Perceptual Filter Model (Figure 1) where you have sensory input into your auditory system. The first filter that influences how you hear and respond to sound is a sensory filter. In our field, this becomes a much more complex sort of issue because we know that the sensory filter is going to be altered somehow with hearing loss. Sensorineural hearing loss adds some distortional element to the way the sensory system works, and that distortional element, in many cases, has a great deal of perceptual variability from one person to another. Added on top of that is how that person’s processing system works. One of the big themes that you hear from my courses is how aging impacts the cognitive system. Aging, in and of itself, changes the way sound is perceived by a person. This is before the sound makes it even to the cognitive filter.

Figure 1. The Perceptual Filter Model, adapted from Bech and Zacharov (2006).

Next is the cognitive filter. These are things like memory, expectation, opinion, likes and dislikes. However, all those things go well beyond the way your perceptual system works. It is all those things that you have an opinion about. You may just like sound sharper or with more bass or with a broader bandwidth, et cetera. It is not just what your perceptual system allows your brain to hear, but also how your opinions about sound affect whether or not you like a sound. Even in our field when we talk about subjective analysis of sound, we tend to focus very much on the sensory part of the filter system, and not on how our peripheral and aging neurological system will influence the way sound sounds to us.

One thing that is interesting about the cognitive filter is that you have to account for all those likes, dislikes and opinions that a person will also bring to the listening task. It is important to remember that, at the end of the day, the person who is paying for the hearing aids and decides if they are going to wear the hearing aid is the same person whose cognitive influences are going to affect whether or not they make a positive decision to use their hearing aids every day.

I want to make the point that we cannot deny the existence of those factors, and, more importantly, that we should respect the patient’s right to have those opinions. We should be trying to assess those opinions and factor them into the way we fit the hearing aid. We work in a very structured way in Audiology. We do real-ear verification of the fitting, we may do some validation using speech-in noise measures or other objective measures. One of the things often missing in our procedure is giving the patient the opportunity to weigh in about how things sound. If we do this, it is usually in the problem-fixing stage. We wait until they complain about something, and then we try to fix it instead of proactively trying to give the patient the opportunity to express their opinion. The sensory filter and cognitive filter will affect the overall subjective assessment a patient has about sounds.

Any given patient is going to weigh these factors differently: how their particular sensorineural hearing loss affects the way sound sounds, how distorted it sounds, how clear it sounds, how well they can process complex information given the potential changes in the cognitive system, whether or not tonal balance is important to them, whether or not performance in difficult environments is important, or whether or not the pleasantness of sound is important. Since everyone is going to have a different set of weighting factors, it is hard to understand how any of those will come together if you are using only traditional audiological measures. In actuality, it is easy to give the patient the opportunity to respond to sound and allow all of those factors to come into play spontaneously when they are making subjective assessments. I will talk about how to do that subjective assessment more specifically in the duration of this talk.

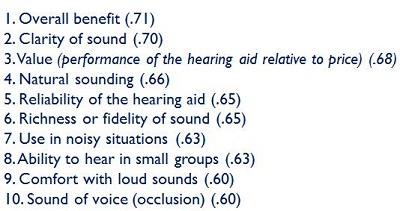

The final lesson that I want to bring up from the last seminar is that the aesthetics of sound matter. The features of sound that we often talk about as sound quality, or aesthetics, do matter to patients. Sergei Kochkin reported on this in his MarketTrak survery in 2010. Figure 2 is a list of the factors that are related to overall satisfaction with the hearing aid fitting process. There are classic audiologically-defined dimensions that should matter to patients.

Figure 2. Factors correlated with overall hearing aid satisfaction (Kochkin, 2010).

As you go through that list, you also realize how many aesthetic aspects are identified, such as natural sounding, fidelity of sound, comfort with loud sounds, sound of voice, and clarity of sound (which is the number-two factor on the list). These are all what I would refer to as aesthetic factors about sound, and these are the factors that we have not assessed much in a structured way when we have given the patient the opportunity to show us how they perform with hearing aids. The reason is that we are so focused on performance. There is no doubt that performance is important, but if you have to listen through a hearing aid for 16 hours a day, 7 days a week, the aesthetics do matter also. That is the one point that we often fail to include in our assessment.

There are many different things that can affect aesthetics including physical fit, spectral balance, loudness, dynamic response of the hearing aids and behavior of the automatic features. We do not typically deal with these unless the patient is complaining about them. Why wait for the complaint? Why not be more proactive about making sure that we have optimized these dimensions first instead of waiting for the patient to indicate later that they do not like the settings?

Using Subjective Assessment of Sound

Let’s get into the practical details. These are some things to strongly think about if you want the opportunity to bring more subjective assessment of sound into your hearing aid fitting process. The first thing we have to settle on is the goal. To me, this is extremely important. Modern hearing aids work very well. They are not a complete solution for sensorineural hearing loss, but when you factor in multichannel, nonlinear processing, automatic adaptive directionality, noise reduction, wireless connectivity, and all the other features that define modern amplification, it is easy to say that we do a very good job of correcting for sensorineural hearing loss. No one is ever going to completely solve sensorineural hearing loss, but we certainly can do a good job considering there is a fundamental distortion of sound as it travels through the auditory system that we have to try to fix before it happens.

The goal of bringing in more subjective analysis of sound on the part of the patient should not be viewed as something to be done to try and make fittings better. It is possible that when you do a subjective analysis of sound, you are going to find specific parameters for some patients where their system seems to work better with one group of settings versus another group. In that case, you truly may improve benefit for the patient. For the greater number of patients, however, I believe that what you are after with a subjective analysis of sound is to get to a point where the patient is satisfied with the sound quality and most satisfied with their entire fitting experience. That is the focus.

One of the reasons I reviewed some of the satisfaction factors was to remind people that there are many different facets surrounding individual satisfaction in modern healthcare. It is not just benefit. It is the total experience with that hearing aid fitting process. By giving the patient the opportunity to express their opinion about how sound is perceived, you are maximizing the opportunity for them to be much more involved and satisfied with their total experience. We expect them to be satisfied with modern hearing aids. Modern hearing aids are good hearing aids, and we know that patients are well-served no matter where they get modern amplification. However, we believe that the professional can take it to the next level by going an extra step in the evolution of the hearing aid fitting process. That is by taking into consideration the patient’s opinions about the sound into the fitting process in a much more structured way.

The goal of subjective assessment in the hearing aid fitting is all about patient satisfaction. If we can improve the fitting, great; but that is not necessarily the main goal. The main goal is to give the patient the opportunity to be more deeply involved as an individual and to create a more personalized solution for that patient so that they can relate to the hearing aid fitting process that the professional has put in place.

Rather than follow the model where we end up fixing a lot of problems, I am recommending a change of mindset on the part of the professional. The first fitting with the patient should be viewed as a provisional fitting. We hope that that fitting works very well. We hope that we have included enough factors about the patient in the fitting process to start the patient with a very good fitting.

One of the good procedural habits that we have in our field is to verify the acoustics of the fitting, such as with real-ear verification. This ensures that we are providing reasonable gain levels to the patient based on their audiogram. It never should be that the verification of fitting targets is the complete objective of the process. That is the start of the process. All you are saying with real-ear verification is that, acoustically, at a very fundamental level, the hearing aid is amplifying enough to make things audible for the patient. I am recommending that you think of that as an initial fitting, but that you bring in more of the patient’s subjective assessment to the way sound sounds through hearing aids. This way, you are moving towards a customized fitting, and one that really reflects the way that particular patient hears and processes sound. The fitting is not complete until the customization process is done.

Not Just Follow-Up

Up until now, there has not normally been formal customization in our process. There is a fitting, and the fitting only changes if the patient complains. Again, I am recommending that there be a provisional fitting, but the fitting is not complete until the patient weighs in on what sounds best for them. It is a change in mindset. Importantly, this approach is not a change in time usage on our part. Because we are spending so much time fixing problems now anyway, it will not consume any more time to make subjective assessments and to customizing fittings for patients. We are already doing that, but we call it fine-tuning, and we tend to do it from a negative view point: “I am the professional. I measure things about you. I gave you a fitting and now you do not like it, and I have to fix it?” From the patient’s standpoint, “I spent a lot of money and it does not sound quite right. I thought you were the smart person who was going to get this to work right for me.” When we knowingly wait for problems to emerge so we can then fix them, immediately we are setting up the entire process to be negative.

However, if the professional says from the beginning, “There are certain things about your hearing that I have measured. I have included those in the way that I set up your hearing aids from the start. But the only one who knows what sound sounds like through your hearing aids is you. There are a lot of other factors that may affect how you want to hear sound through your devices. The only way that I know that this setting sounds the best for you is to give you the opportunity to listen to the hearing aid, and for me to have the opportunity to make adjustments to optimize the hearing aid so that you really like it.” Simply changing that language from a negative to a positive will really make it personal and customized for the patient. That is the mindset that I am encouraging you to consider.

Let me be clear in saying that this does not mean that prediction is not important. Prediction is important because we want to start the patient out well. The point is that it is an admission, a recognition, that our predictions are never going to be perfect. There is a lot of emphasis in our field on evidence-based practice, which is the way that it should be. Any medically-related practice should be evidence-based. Part of our evidence is the fact that there is a lot of individual variability. Just measuring the audiogram or even loudness dynamics never captures everything we know about the way that sounds are perceived. A fitting is never going to be complete until we somehow factor in all the sources of variability. In my opinion, we are never going to be able to measure enough dimensions to capture all of those sources, and we can never estimate how every individual weighs all the possible dimensions.

I will be very clear with you right from the start. This idea of including more subjective assessment in the hearing aid fitting is not an exact science. I cannot give you a 20-step process to follow that will leave you with the most satisfied patients in the world, and not everyone is going to follow the exact same 20 steps. This is where professionalism and clinical knowledge comes into place. I am going to try to frame out some ideas about how you can do this, and then it is up to you as a professional to use the patient’s subjective response to sound as a source of information to affect the fitting.

There are lots of sources of information that the patient will give you. They give you the audiogram including speech recognition and loudness limits. They talk about sound. They tell you about what their experiences were when they listened to the hearing aids, including where they did well and where they did not do so well. A new source of information that we typically do not use that I am encouraging you to use is to allow the patient to listen to sound, respond to sound, and then take what the patient says in response to sound and factor that into your fitting also. Again, this is not an exact science, but we are a clinical field. Part of the responsibility of the clinician is to factor in many different aspects about the patient to decide on treatment options.

Putting in Into Practice

If we are going to include more subjective input from the patient, the question is, “When we can do this?” The two major times that I want to talk about are at the initial fitting and also some sort of follow-up session. When I talk about a follow-up session, I am going to use the term optimization session because this should be a positive, proactive thing, not fixing problems.

At the initial fitting, I think it is possible to use some level of subjective analysis of sound. This can be tricky, depending on if you are fitting a first-time user or an existing user. Having a subjective analysis of sound is based on the assumption that you have access to recorded sounds to use in your clinic. Many companies now have recorded sounds in their fitting software. Those of you who use different software know where it is. If it is not in your fitting software, there are other ways you can get libraries of sounds, but the easiest way is to get it out of the fitting software.

If you are dealing with a first-time user, one of the points that we at Oticon have made for a number of years is that first-time users are not a good source of information to draw from in order to do fine-tuning at the initial fitting because they are not used to listening to amplified sound. We have tried to discourage much of the fine-tuning at the initial fitting, because the patient just does not have the experience to respond to amplified sound. However, the average patient has been listening to sound for an average of 72 years. Just because they are not wearing a hearing aid does not mean that they do not have opinions about sound. At that point in time, there is an opportunity to make an assessment about whether or not they like things with, for example, more treble or more bass, by either asking the patient or playing sounds. If you have fitting software that allows you to turn the high and low frequencies up or down, then that is a good opportunity to get a sense of how they respond to sound to some degree. Any response you get from a first-time user at the initial fitting should be taken with a grain of salt. If they have not heard many high-frequency sounds for an average of seven years, then those might sound strange or unnatural to them at first. I think the better place to make an assessment is in the optimization session, once they have had an opportunity to adapt to amplified sound. But that does not mean that you cannot get some input at the initial fitting.

For an existing user, I think you can get good input at the initial fitting. Certainly, you can talk to them. If they are coming in to replace a current set of hearing aids to a new set of hearing aids, it is important to get a sense for what they liked about the sound of the old hearing aids versus the new hearing aids. Sometimes it is something you can reveal just by asking the patient, but you can also play different sounds that should tap into different aspects of their old hearing aids to get a sense about what they like about the sound quality.

Especially with existing users, it is not just about spectral balance. It is about other things, such as how aggressive the hearing aid is with its automatic functions. Most modern hearing aids have automatic functions such as directionality, noise reduction, et cetera. Some patients like these systems to be more active than others. It might give you some knowledge of how you want to include the patient’s reactions into a new fitting. I would strongly encourage you to wait until the patient has had an opportunity to listen to the devices for a while before doing the majority of the optimization.

When most existing users get a new set of hearing aids, there will be something new with the sound processing that they did not experience when they bought hearing aids five years ago. You want to give them some time to get used to the way the new hearing aids are sounding. For an existing user, it is probably on the order of one or two weeks. You probably do not want to make too many subjective assessments right when you fit the new hearing aids. Maybe you will find that you can do it, but to me that feels a bit soon. The adaptation process for first time useres may be different for everyone, so your waiting period will depend on each patient and how much time you gauge they will need. At Oticon, we tend to believe that the adaptation process is, on average, around four weeks or so. That is not a hard-and-fast number, but that is a number with which we are fairly comfortable.

For a new user, that does not mean that you do not see the patient in follow-up in the interim. You do need to follow whatever protocols you normally use with a first-time user. If you bring them back after a couple of days or at the end of the week to check how things are going, all that still needs to be done, but this idea of bringing in their opinion of amplified sound should wait several weeks.

In terms of the actual subjective assessment, I do not think you need to be particularly fancy. What you are dealing with are mostly reactions to sound quality. This is not something that I think you have to put the patient in the sound booth to do. To me, it feels much more natural to do it in your normal counseling setting, especially since there has been a movement over the last 10 years to let the patient see the fitting screen and to use sound more often in the fitting. Many audiologists I know now have larger screens that the patient can see. They have table-top speakers that are attached to their fitting software so more sound can be included in the process. A lot depends on the fitting software, but it does not have to be a sound booth set up. I think it is important to compare settings in the hearing aid pretty quickly. If you are making changes to the settings and asking for immediate feedback, you have to be hooked into your fitting software to do that. There are not a lot of practitioners who have a setting where the patient is connected to the computer in the sound booth. When you are focusing on sound quality, I think that is fine because this is not a highly calibrated task. This is more of a paying-attention-to-what-the-patient-says task. You will want to make sure that you are in an environment that will let you have a natural discussion with the patient.

Selecting Sounds

When it comes to selecting sounds to which you want the patient to listen, one of the best guides is by what seems to matter to the patient. If they are very focused on music, then you want to play music samples to them. If they have talked a lot about noticing difficulty in a restaurant during the adaptation process or they did not like the way the hearing aid sounded somewhere, you want to try to replicate those situations, although I will address noise scenarios later. If they talk more about sitting around and watching television at home and that seems to be important, you want to try to optimize that. Then you would pick sound samples that make sense there. This is the point where the session becomes very patient-driven.

If there are multiple sounds available in your fitting software, you definitely are not going to play all of them to the patient. That would be way too much time to spend with your patient. You do want to pick sounds that seem to matter to the patient. Since you are focusing more on sound quality issues, patients are going to be more sensitive to quality for sounds that matter to them. If they never listen to classical music, then having them judge sound quality on classical music does not make a lot of sense, as it is not an important sound to them. If listening to television is very important to them because they feel a little isolated and get a lot of information from the television, then that is what you want to use. If they are very social and they like to be out in noisy environments and those situations matter to them, then you want to assess using sound samples like that. I would definitely let the patient’s opinion drive which sound samples you use.

I do want to make an observation that is important to distinguish between sound quality and overall performance. If a patient comes back in after using the hearing aids for one or more weeks, and they report difficulties in some key listening environments that include noise, it may seem natural that you would then play a speech-in-noise sample to the patient and try to maximize sound quality. However, that is getting off-task a little, because the patient is concerned about their performance in these environments. It is very difficult to replicate true complex sound environments in the office. Even though the sound sample says “speech in a restaurant,” you are really not replicating the true acoustic environment of a restaurant. You are not getting all of the directional or the reverberation characteristics. I think that it is a little naïve to think that you can solve a performance issue in a noisy environment by having them listen to sound samples in your office. It might make the patient have more confidence in the process if you play those sound environments, but as an audiologist I think you need to be realistic and recognize that you may not solve the problem by doing that. There is still a place for adjustments you would make in the normal counseling session you have with the patient, stating that you are going to make some adjustments because you think they will help them out in those difficulty environments more, but that they will not know if the adjustments helped until they go back out into those environments.

The analogy I like to use is shoe shopping. You want to buy a pair of shoes that are going to be comfortable to wear all day and also stylish. When you go to the shoe store, you can take a look at them and think that they will fit and have good padding. You would not pick them up unless you liked the way you looked. However, you will not know if they are going to be comfortable all day until you wear them. It is the same thing with hearing aids: they may look great, but performance is unknown without experience. That is why I am talking so much about judging aesthetics in this session. I know aesthetics are not the only thing that matter in a fitting session or that improves satisfaction, but they are the things that you can assess quite easily in the office environment. You might as well do what you can do in the office well. That is not a substitute for good knowledge about how to adjust a fitting to improve its performance in difficult environments, though.

Also, getting the aesthetics right tends to be more of a positive thing. When you go shoe shopping, it is not like you start with the ugliest shoes in the place and work up to the most beautiful. You start with the ones that you like and then find the ones that you really, really like. It helps to put more of a positive spin on the process by focusing on the aesthetics during the assessment of sound quality in the fitting process.

Assessment Strategies

One of the things to know when making a subjective assessment is that the easiest judgment for a listener to make cognitively is A versus B. “Do you like this better, or do you like that better?” It is like if you go to a wine-tasting, and then you have to rate it on 20 dimensions. That idea of judging on multiple dimensions with terminology becomes a little difficult. We have this tendency to cross sensory judgments when we use words to describe sensory experiences. Sometimes that gets complicated. It is a lot easier to listen to sound and pick the sound that you like better than to use words to describe sounds. You might not be able to describe the taste of Coke versus the taste of Pepsi, but you know which one you want.

When faced with a simple, clear "this-or-that" decision, most people will have an opinion. I would recommend that when you do the subjective assessment of sound quality that you do A-B comparisons. Set the hearing aids up to operate one way; then set them up to operate a different way, and ask which one the patient likes more. Sometimes the patient will have clear opinions and sometimes they will not. If the patient can hear a difference and has a strong opinion about it, then that is something you want to factor in. If they cannot hear the difference, or if they can hear the difference and do not have a strong opinion about it, that is also information that you have learned.

I would also recommend classic bracketing procedures. If you are giving the patient two different sets of settings to listen to within the fitting software, start with bigger differences. If they can hear the differences, then you might want to narrow it down. If they cannot hear a difference, then they simply may not be sensitive to that dimension. Maybe you did something such as turning up the high frequencies or changing the directionality, but maybe if you went in the opposite direction, they would hear a difference. Again, as I said, this is not an exact science. This is accumulating knowledge about the way the patient hears sounds, trying different dimensions, seeing what they seem to respond to and using that information to go to the next step of the fitting process.

Clear and Pleasant

The next recommendation that I would make in terms of what you should have the patient listen for is the group of settings that provide a clear and pleasant sound quality. There are very specific reasons why I recommend using this terminology. Gabrielsson published work in the 1980’s where he examined the way we perceive and describe sound (Hagerman & Gabrielsson, 1985; Gabrielsson, Hagerman, Bech-Kristensson & Lundberg, 1990). The single factor that related most strongly to overall sound quality ratings was clearness. The more clear the speech sounds, the higher the overall sound quality ratings. That was done in both non-hearing aid sound amplifying systems, like stereo equipment, and also in hearing aids.

We know that speech clarity is a very dominant dimension. Pleasantness is also included in there because it is a very good balance term to clarity. Clarity and pleasantness have been used in a variety of different studies together. We know that to make speech very clear, we tend to turn up the high frequencies or lower the compression a bit. But we also know that one of the risks with that adjustment is creating discomfort or some other unpleasant listening experience. By having the patient factor in pleasantness at the same time, the patient is balancing those two factors. You do not have to do that. I am not recommending that you first assess clarity and then assess pleasantness, but rather put it on the patient to assess those two together. This gives them two things to listen to, A versus B, and then they can decide which one provides a clearer and more pleasant speech signal, weighting all the other personal factors they might have. It is a very nice combination of terms to allow you to get at a final solution.

There are a lot of factors that can make sounds unclear and unpleasant. Instead of trying to find all of those, just focus on clear and pleasant. There is no reason for you to worry about what the negative dimension is. All you want to do is focus on moving towards the positive. If the patient says, “I do not like it because it has too much echo,” then you need to solve that problem. You can solve that problem by moving towards the positive which would be a clear sound. If they said it is too harsh or too sharp, it is important to know that, but the way you make that go away is to move in the direction of pleasant. So, when you combine those two terms and focus on finding the most positive setting for the patient in that area, then you know that you are moving in a positive direction for the patient.

Importantly, if there is something else that matters to the patient, you should use that as the criteria. If the patient comes in after they have worn the hearing aids for a while and keeps talking about a certain issue or word like echo, then use that word to have them judge things. If they do not have a specific word that they tend to use, then you might want to go back to clear and pleasant.

Without a doubt, there is still a role for traditional fine tuning. There are some things that you are not going to solve with a subjective assessment of sound. If things are too sharp or too loud, then you still may do the fine tuning that you always would do in follow-up. I am not saying that this is a substitute for fine tuning, but this is an addition to the normal problem-solving that you would do. That is part of the normal counseling process with the patient.

Control the Process

There is no doubt that the professional’s job is to control the process. It is very easy to let a process like this get out of control where you are searching in multiple dimensions, playing with this setting and that setting. Remember the goal. The goal is satisfaction, and we believe that an important driver in satisfaction is giving the patient the opportunity to express their opinion about sound. When you are setting up the assessment, make sure that you keep coming back to the idea of whether or not the patient seems to be feeling good about the process. If the patient is getting frustrated because they cannot hear differences between A and B, then you need to gracefully move away from that, because it is a task that they cannot do. Most patients can tell you whether or not they like the way A or B sounds. You want to make sure that the patient is satisfied at the end of the day; you do not want to drill down, and find the smallest corner of their fitting and try to maximize it. The whole idea is making sure that the patient really feels that their opinion matters and that you took the time to ask them their opinion about the way sound is perceived.

Conclusion

I already talked about the time issue at the beginning of this course, and I know one of the first objections that many people will have is that a subjective assessment will take a lot more time. The reality is that it is not going to take a lot more time. You will use the same time that you are spending on average with patients in follow-up solving differences, but you will be using that time in a more proactive way. I would be surprised if you end up feeling like you are using more time doing this.

To sum up, I am advocating that this is a change in mindset on the part of the professional. It is a change in mindset of what the hearing aid fitting process should feel like to the patient. I am encouraging us to focus on proactively planning to assess the way the patient hears sound, factoring that in to the way we go about making adjustments in the hearing aid, all with the goal of trying to maximize satisfaction with the hearing aid process for the patient. Prediction is important, but it is a realization that we are never going to predict how all of these factors come together for any given patient. We can make small, but important, adjustments to the way we carry out our fitting process to make it more patient-centered.

References

Bech, S., & Zacharov, N. (2006). Perceptual audio evaluation: theory, method and application. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley.

Gabrielsson, A., Hagerman, B., Bech-Kristensen, T., & Lundberg, G. (1990). Perceived sound quality of reproductions with different frequency responses and sound levels. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 88, 1359-1366.

Hagerman, B., & Gabrielsson, A. (1985). Questionnaires on desirable properties of hearing aids. Scandinavian Audiology, 14, 109-111.

Kochkin, S. (2010). MarkeTrak VIII: Consumer satisfaction with hearing aids is slowly increasing. The Hearing Journal, 63(1), 19 - 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30-32.

Cite this content as:

Schum, D.J. (2013, February). Providing structure to the subjective hearing aid evaluation. AudiologyOnline, Article #11497. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.