Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live webinar. Download supplemental course materials: course handout, white paper, HyperSound Clear brochure.

Learning Objectives

- After this course, participants will be able to define high value care.

- After this course, participants will be able to define patient-centric care.

- After this course, participants will be able to implement a clinical strategy that includes the use of alternative and complementary devices.

Dr. Brian Taylor: Today, I want to talk about some industry challenges and opportunities as they relate to the aging population and the influx of baby boomers. We will talk about some alternative and complementary devices, one of which is HyperSound, and why and how that might be a viable treatment option for patients. Finally, because it is a unique and novel device, we will spend some time reviewing how ultrasonic transmission of audio signals work.

The overarching theme today is that there are a constellation of forces at work in the marketplace, and those forces need to be viewed as opportunities. One of the ways we can respond to these market forces, is by offering more complementary and alternative treatment approaches for our patients with hearing loss. How do we broaden our scope of offerings? Hearing aids are the gold standard treatment choice for many of our patients, but are there some opportunities outside of that?

Healthcare Trends

If there are two themes that encapsulate what healthcare trends are about, they are value-based and patient-centered. We are moving towards value-based healthcare and patient-centered care. Some of the reasons for this are obvious. People are more educated and have more information at their fingertips. They want to participate more in the process and are more concerned about healthy lifestyles throughout the lifespan. Patient-centered care takes on greater emphasis in that type of marketplace. At the same time, we know that value has become synonymous with the changing healthcare landscape because of the costs associated with healthcare. How do these terms relate to audiology and hearing care?

Healthcare costs have skyrocketed well into the billions over the last 30 to 40 years, even adjusted to inflation. A large part of this cost is related to taking care of older individuals, many of whom we see in our own practices. The United States has not fared as well at keeping those costs down in the older population as have other countries. As people get older, they become more expensive to take care of because they are more likely to have issues with chronic conditions as a function of age.

If you talk to economists, about one-quarter to one-third of the costs associated with those higher risk patients could be avoided if we identified and treated episodes of illness sooner, and focused more on preventative care. I would argue that audiologists and hearing instrument specialists have some unique opportunities to help lower these costs by participating in preventive care. While it is beyond the scope of today's talk, I think there is a tremendous opportunity to practice interventional audiology. Interventional audiology can play a small but very important role in managing costs, and staving off the long-term effects of some of the chronic conditions associated with hearing loss.

Value-Based Care

To give you a better appreciation for why value-based care has become such an integral part of the changing healthcare landscape, let us compare the United States healthcare market with four other countries: Germany, Sweden, United Kingdom and Spain. Healthcare costs across these five countries are relatively similar until patients get into their 60’s. At that point, the United States has astronomically higher costs relative to those other four countries. These are some of the reasons why you are hearing a lot of talk from the government and regulatory bodies about the importance of value-based care.

In the United States, there are 48.1 million individuals that have some degree of hearing loss. As people get older, the prevalence of hearing loss increases significantly. We know that four out of 10 individuals between the ages of 60 to 69, for example, will have some degree of hearing loss. When individuals are in their 70’s, five out of 10 will have a hearing loss. Finally, in individuals 80 and older, eight out of 10 typically have hearing loss.

There is opportunity around value-based care. We know that insurance companies, individuals, Medicare, and other governmental bodies are looking for the best outcomes at the lowest costs as well as safe, appropriate, and effective care with positive long-term results. In addition, they expect the use of evidence-based decision-making and proven treatments that take into account the patient’s wishes and preferences. In a nutshell, that is what value-based care is about. How do we fit in to the larger picture of value-based care?

Patient-Centered Care

Patient-centered care is integrally linked and associated with keeping costs down and getting patients more involved in their care at a younger age. In addition, patient-centered care refers to patients participating in their own choices with respect to healthcare. Within hearing care, some of the experts who have done important research and publications in this area are:

- Laya Poost-Foroosh, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto; audiologist who has done research on patient-centered communication and what that entails.

- Jill Preminger, University of Louisville; prolific researcher who has done some groundbreaking research on the dimensions of trust and how trust fits into the larger clinical audiology picture.

- Caitlin Grenness, University of Melbourne, Australia; research audiologist who has done research around individualized care.

This patient-centered care movement goes beyond the United States. We are seeing Canadian, Australian, and European researchers publish and lecture about it. We need to pay attention to this and think about how we implement this movement into our own practices with patients on a daily basis.

Let’s look a little more closely at what the work of these three researchers. Dr. Grenness in Australia has published on what she calls “the therapeutic relationship.” Much of her research focuses on recording and analyzing the dialogue between patients and audiologists. She did an interesting paper earlier this year that showed that audiologists almost immediately jump into the technology conversation when talking with patients. Audiologists spend an inordinate amount of time talking about technology and less time talking about the individual desires and needs of the patient. The therapeutic relationship should include how we get the patient more deeply informed with what they need to make an intelligent decision about their treatment. How do we get them more actively involved in the process of making that decision? How do we practice individualized care? In her work, those three terms - inform, individualize, and involve - are the pillars of the therapeutic relationship.

Dr. Preminger has done work on the role of trust in the patient/provider relationship. She recently published in a paper the International Journal of Audiology about four different dimensions of trust. The first dimension is the components of trust, and one of those is the clinical environment - how your office looks and with whom you are associated. One is the commercialized approach; that may be how much or how little you are trying to talk someone into taking an action such as buying a hearing aid, which is also related to marketing and advertising. Then there is the technical competence and relational competence; this would include interpersonal skills and communication styles, such as your ability to express empathy. Dimension I is quite lengthy.

There are three other dimensions of trust which you can explore on your own, but trust is a cornerstone of the therapeutic relationship, and that trust level can evolve over time.

The last part of patient-centered care I wanted to talk about comes from Dr. Poost-Foroosh and her work in Canada. I find her work to be very practical, because you can put into action her suggestions. Her research talks a lot about the dimensions of patient-centered care.

There are six steps of participatory care, and this does not come specifically from her work, but rather from work about motivational interviewing. There is a movement within medicine for more and more physicians to practice participatory care. If you boil that down five some manageable steps, they are ensure patient comfort, consider patient motivation and readiness, acknowledge the patient as an individual, provide useful information, and facilitate shared decision making.

Imagine you are face-to-face with an individual that is seeking services from you for the first time. How do you bring participatory care to life? It is by practicing the six things:

- Define scale and scope of condition

- Generate and evaluate alternative solutions

- Decide on a mutually acceptable solution

- Implement a solution

- Evaluate the effectiveness of a solution

- Provide feedback and service over time

You can implement these things by putting into place the five steps mentioned previously. This is why having complementary and alternative technology as a treatment or remediation solution is important. You want to make sure that whatever you are offering the patient is in alignment with their expectations and their current level of motivation and trust.

When providing useful information, we want to make sure that of all of our possible choices from treatment to remediation options, one or two of them might be useful for that patient at that point in time. This gives you a lot of information and a roadmap of how you might implement patient-centered care and communication in your own practice.

Super Convergence of Market Forces

Sticking with the theme of the changing marketplace and the role of hearing care professionals in it, I wanted to talk about what I call the super-convergence of market forces. There are three forces with which we need to wrestle as a profession and figure out exactly how we add value to the patient/provider relationship.

The first of these three forces is the rapidly aging population. Another part of this convergence would be age-related hearing loss. We know from research published over the last three to five years that age-related hearing loss impacts all facets of life, including increases in hospitalization (Genther, Frick, Chen, Betz & Lin, 2013) and early death (Contrera, Betz, Genther, & Lin, 2015). Contrera and colleagues (2015) showed that the more severe your hearing loss, the more likely you are to die at an earlier age. It is important for us to not overstate and use that as a scare tactic, but to realize that hearing loss has a wider breadth of consequences than we originally thought. The third element of this super-convergence is the disconnect between access and innovation.

The Graying of America

I want to talk about the rapidly aging population and how audiology fits in. I want you to imagine that you have randomly selected 100 individuals from a village of 10,000 people. In that randomly selected group, we know that 12 of those individuals are likely to be 65 years of age or older. Of that group of 12 that are 65 or older, probably 8 of those individuals has some degree of hearing loss. That is how the statistics stand today.

If you were to go back to that same village 15 years from now and randomly selected another 100 individuals, about 20 of those individuals are likely to be 65 years of age or older, and 14 of them are likely to have some degree of hearing loss (Hannula, Bloigu, Majamaa, Sorri, & Maki-Torkko, 2011). We are talking about almost a doubling of the number of people that have a hearing loss from that age group. If you are a younger audiologist, you may look at this as both an exciting challenge and as an exciting opportunity to take care of more people. There also might be a bit of a bottle-neck when you realize that the number of audiologists is diminishing over time, and the number of people aging is rapidly increasing. This gets at why government organizations like the Institute of Medicine are looking at issues related to access.

Let’s look at some of these numbers in relation to hearing aid use. I want to build an argument about why audiologists and hearing care professionals need to broaden their scope of options for patients with hearing loss. Think about the shape of an upside-down pyramid. At the top, 7.3 million Americans over the age of 80 and above have a hearing loss (Lin and Chin, 2012). Twenty-two percent of that group have hearing aids. In the next group of 70 of 79-year-olds, 8.8 million have a hearing loss, and 17% of them wear or have hearing aids. In the 60 to 69-year-old group, 6.1 million have hearing loss and 7% have hearing aids. Four and a half million Americans between the ages of 50 and 59 have a hearing loss, and only 4% of them have hearing aids. There are some tangible opportunities when you look at prevalence of hearing loss by age and where some of the shortcomings are within the market. There is room to grow the hearing aid penetration rate, but I would argue that there are opportunities here for people challenged with hearing loss to use alternative or complementary technologies.

Some of the people 80 years and older may not wear hearing aids because of cognitive and physical conditions that preclude the consistent use of hearing aids. Perhaps an alternative device or treatment options might be useful for them. For the 50 to 59-year-olds, 11 million have hearing loss, and the penetration rate is probably around 5%. That suggests that stigma may be a concern, and perhaps some other alternative device or technology might be amenable to that group, especially those who have milder hearing loss.

Another way to look at the untapped market potential is hearing aid prevalence as a function of degree of hearing loss. In the U.S., approximately 5% of the hearing-impaired population have a profound hearing loss, and 70% of them wear hearing aids or cochlear implants, while the other 30% are probably part of the deaf community and choose to rely primarily on sign language. Next, we know that about 20% of the hearing-impaired population in the U.S. has a moderate to severe loss. Hearing aid use is around 50%. There is obviously room to grow that channel of the market. The vast majority of individuals in the U.S. with hearing loss are have mild to moderate or high-frequency hearing loss, yet only 10% of them have traditional hearing aids, whereas 90%, decide not to go the route of using amplification, be that for reasons of stigma, cost, of the perception that hearing loss is not severe enough yet.

One of the take-aways from this is that we are dealing with two separate markets that value different things. The top 25% of people are in the medical channel. Those are the patients who are most amenable to the solution that we have offered over the last several generations of audiologists. There is a customized fitting with numerous office visits. Everything is predicated around customizing a solution using hearing aid software and multiple office visits. This is a great model for someone who has a more significant hearing loss and needs the extra time and attention. The larger majority of people with mild to moderate hearing loss are more in the consumer electronic channel. They are not willing to go through the numerous office visits, different options, programmability, and customizability. They are more amenable to something that is quick, off-the-shelf, and a one-size-fits-all approach. In all likelihood, we are dealing with two separate markets that value different things, and as an audiologist, you have to decide if you want to be involved in both of these markets. What works for attracting the top 25% with more severe loss to your office probably does not work the same for the bottom 75%. Keep in mind that as people age, their loss is likely to worsen, and people move from the bottom of the pyramid into the top over time.

Hearables

We are seeing the morphing of two divergent types of technologies (hearing aids and consumer electronics) into this new category called hearables. We know both the positive and negative attributes of a hearing aid. Hearing aids are customizable. Several appointments are needed to get it right. A professional needs to be involved in the delivery of that product, and hearing aids do carry a higher price point because of the extra personalized service. Hearing aids, for various reasons, tend to be stigmatizing, although I would argue that the effect has diminished somewhat over time.

On the other end of this equation, you have consumer electronic products. They are off-the-shelf. They have mass appeal and what I call the “fun factor.” Because they are off-the-shelf, they are sold at a lower price point. Because of the fun factor, they offer some immediate gratification.

Hearables are the product of these two product categories. While I am not an expert in this category, I do think that hearables offer a lot of possibilities for our patients because they can offer the best of both worlds. They can be customizable. They have a cool factor. They are more or less off-the-shelf. Because of the cool factor, there might be some immediate gratification. The morphing of these two technologies offers audiologists unprecedented opportunities to tap into some of the markets that have been historically under-penetrated.

Mild Hearing Loss

I want to focus first on mild hearing losses. Many people with even a slight hearing loss experience activity limitations and participation restrictions. It was always very frustrating to me when a patient would describe significant struggles in daily communication and then you would find normal or only slight hearing loss. That makes it difficult to offer a treatment plan.

MarkeTrak data (Kochkin, 2012) shows that 43% of these patients with milder hearing losses are often given a wait-and-retest approach. It makes sense for a lot of these patients as we do not have anything valuable to offer them. They are not hearing aid candidates by any traditional definition. The patients are more or less told to wait, and when it gets worse, we will take care of them. That does not negate the fact that they continue to struggle with specific listening situations.

Another area of research that is uncovering some opportunities for us is the category of hearing difficulties with normal audiograms. A study by Kelly Tremblay and colleagues (2015) at the University of Washington found that 12% of adults between the ages of 21 and 84 have hearing difficulties and normal hearing tests results. The overall prevalence of that condition is 3%. Three percent may not sound like much, but when you recall that the overall prevalence of hearing loss is around 15%, 3% is a fairly big number that you would put on top of the existing prevalence of hearing loss. These are individuals that struggle with communication on a daily basis, but have normal test results.

We also know from Chai and colleagues (2007) that over half of adults aged 49 and older report hearing difficulties, and half of that group have normal audiograms. Even older than that, 60% of individuals 54 to 66 report difficulty following conversations in noise (Hannula, Bloigu, Majamaa, Sorri, & Maki-Torkko, 2011). We know that this problem exists, and it is frustrating because we cannot measure it using the traditional yardstick of the audiogram.

Many of these patients are not considered hearing aid candidates because their loss is not severe enough, and even if they did have a more significant hearing loss, many of them, for whatever reason, are not ready to be hearing aid wearers. In fact, some of the more recent research shows that just because a patient comes into your audiology practice does not automatically imply that they are seeking hearing aids (Claesen & Pryce, 2012).

Other research has shown us that when patients are offered alternative options to traditional hearing aids, more than half of those patients with hearing loss will choose one of the alternative options (Laplante- Levesque, Hickson, & Worrall, 2012). I think it is imperative for all of us to think about what some of these alternatives and complementary devices that we can add to our practices that might broaden our appeal.

Leisure Time

How does the typical adult spend their leisure time? One of the privileges of modern society is we have all kinds of gadgets that we can use for almost unlimited access to entertainment. Compared to 50 years ago, people have more leisure time today than ever before in human history.

Believe it or not, television watching is the most popular leisure activity for the majority of adult Americans. A study published in the New York Times in 2012 showed that the average American watches five hours of television per day. That number has probably grown over the last few years when you start to include streaming audio on smartphones and tablets.

As a percentage, adults spend more than 50% of their time watching TV. Across the board, regardless of age, television watching is by far the most popular leisure activity. In fact, you could take all of the other leisure activities combined such as reading, relaxing and thinking, participation in activities, socializing and communication, and together they would not equal the popularity of watching television.

There are a lot of people with milder hearing losses that are told to come back and get a retest, and when it gets worse, we will offer them a set of hearing aids. However, they continue to struggle in situations where it is important for them to hear better, such as in their leisure activities.

That brings me into a conversation about some of these alternative technologies available. The specific one I want to talk about is the product that I represent, HyperSound. Think about this product as an alternative or a complement to traditional hearing aids. There are three categories of patients that it may benefit. The first is existing hearing aid users who continue to struggle with the TV. The second group are older patients, 80 and above, who might be suffering from a cognitive or physical condition that prevents them from wearing traditional hearing aids. The last group is younger patients with milder hearing losses who, because they are either too young to admit it or the loss is too mild, they are not traditional hearing aid candidates. HyperSound meets the needs of these three potential categories of patients.

HyperSound

One of the benefits of HyperSound is that unlike traditional assistive listening devices (ALDs), a person simply sits down in the beam and they can watch television with their family and friends. There are no devices that they have to place on their ears. There are no cords or wires to place around their neck. That adds to a level of inclusiveness, participation, and enjoyment while watching television that is unprecedented in relation to traditional ALDs and hearing aids.

HyperSound is shown in Figure 1. It has two speaker-like devices called emitters. Those plug into an amplifier, and the amplifier plugs into any modern television or cable box. You can also plug it into a smart phone or an iPad. It directs a very narrow beam of sound directly to the user.

Figure 1. HyperSound device.

Unlike conventional audio that fills the entire room, HyperSound travels in very directional pattern. Because of the way it works using ultrasonic technology, there is very little dissipation of the energy over distance. The inverse square law dictates that for every doubling of distance, there is a 6 dB reduction in sound intensity. With HyperSound, there is some reduction, but it is not nearly as much as with conventional audio.

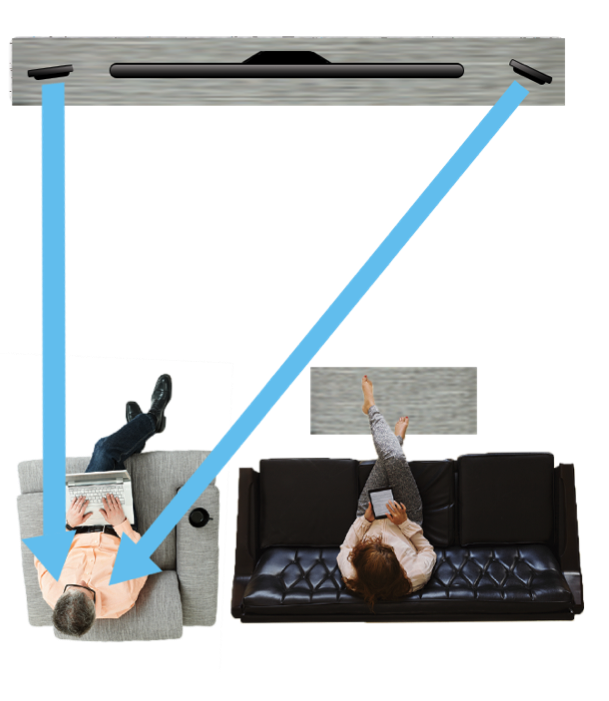

The concept is that a person sits down in the beam and they can hear the television very clearly. Figure 2 shows an aerial view of HyperSound. It utilizes a 100 kHz carrier frequency to transmit audio in the air to the patient in a very narrow beam. The person on the chair where the arrows are pointing is the person in the beam. That person can watch television and hear it very clearly through the HyperSound signal while their partner hears the audio through the regular television speakers. HyperSound uses ultrasonic energy to transmit the sound and creates the sound in the air. It essentially sounds like you are listening closely or with headphones on.

Figure 2. Aerial view of HyperSound’s transmission across a room.

Using HyperSound in your Practice

People with mild hearing loss or those who are existing hearing aid users that struggle with the TV and those that cannot wear hearing aids because of a cognitive or physical condition would be great candidates for this type of technology. It is more inclusive. It adds to greater enjoyment to a popular leisure activity – watching television.

The way you would implement this complementary or alternative technology into your practice requires changing how you might conduct business in your practice. If you wanted to implement this technology, I think it is important that you attract younger adults and individuals who ordinarily would not consider themselves hearing aid candidates. You want to find ways to attract them to your practice and demonstrate this new technology. It is typically people who are under the age of 60 or 65 who do not consider themselves as handicapped or old, but yet they struggle when you ask them questions with dialogue on the TV.

You may have to do a few small things differently in your practice in order to identify the real need. One of the issues might be identifying when someone is a hearing aid candidate and when are they a candidate for HyperSound. One way to differentiate would be to use some type of self-assessment tool. One that has been used in Australia is called the Reported Assessment of Communication Abilities or the Patient Assessment of Communication Abilities. This is a simple questionnaire that helps you determine how much difficulty patients are having in very common listening situations.

Another way to identify who might be a patient for HyperSound over hearing aids might be to use a patient decision aid. One of these aids, created by Barbara Weinstein and Jill Gilligan, Listening to Television with a Hearing Loss, helps a patient step through the process by answering a series of questions, and places them in a category whether they are more of a candidate for HyperSound or for hearing aids. Decision aids are a way for patients to more actively participate in the process and logically come to their own conclusion about which one they might want to try first.

Another version of the patient decision aid that has been written about in the literature shows a patient all the possible options, and they decide. The choices include hearing aids, hearing management group, directed audio (which is the generic name for HyperSound), hearing assistive technology, cochlear implants, and no treatment. The idea here is to educate the patient on the one that would be most appropriate for them, talking about the pros and the cons of each.

If you are going to implement HyperSound in your practice, it is important that you demonstrate it. The technology is unlike anything you have ever heard. It has an incredibly broad bandwidth, where high frequencies extend beyond 12000 Hz. You get a maximum of 30 dB above 8000 Hz, which provides clear amplification of consonant sounds. Rather than me talking more about how it works, I would encourage you to get a demonstration of it so you can hear for yourselves. Once you have listened to it, you will want to demonstrate it to your patients so they can realize how it sounds. Demonstrating in your fitting room would be the ideal way to showcase HyperSound.

How do Patients Like it?

I was involved in a study that was published in the Hearing Review, where two independent practices asked 58 randomly selected patients to listen to HyperSound for about two minutes. These patients sat down and listened to a variety of audio clips. None of the patients were wearing hearing aids, and then we rated their overall impressions of HyperSound.

What we found was phenomenal. The overall listening experience on a 1 to 5 scale showed the vast majority of people rated it very good to excellent. Only one patient rated it poor, and four rated it fair. Everyone else rated it favorably.

We also asked them to give us their perceptions of intelligibility improvement. We did not objectively measure speech intelligibility, but we asked the patients if it seemed to improve their ability to understand speech from the TV. Nine of the subjects said there was tremendous improvement; they heard every word. Another 37 subjects had marked improvement and eight of them had some improvement, with 10 of them between improvement and some improvement. Only two out of the 58 said there was no improvement at all.

Finally, we asked the subjects if they would be willing to purchase HyperSound at a price point of $1,500. The majority of the participants said maybe, probably, or definitely. When you demonstrate it and present it as a complement or alternative to hearing aids, a lot of patients find this to be an effective technology.

If the patient likes it, you can send them home with the unit. We offer a solution with Caption Call, where they get home installation. It is pretty easy to install, but we want to make sure patients get it right.

Connecting a Patient

The patient does not have to wear any accessories with this device. Normal-hearing people can listen to the television at the same time they do. There is no internal delay. Background noise is no longer an issue. HyperSound is similar to a hearing aid in the sense that it is programmable with NOAH-compatible software. It uses NAL targets as a starting point to calculate the gain, and there are multiple channels. With these features, HyperSound is more like a hearing aid than a consumer electronic.

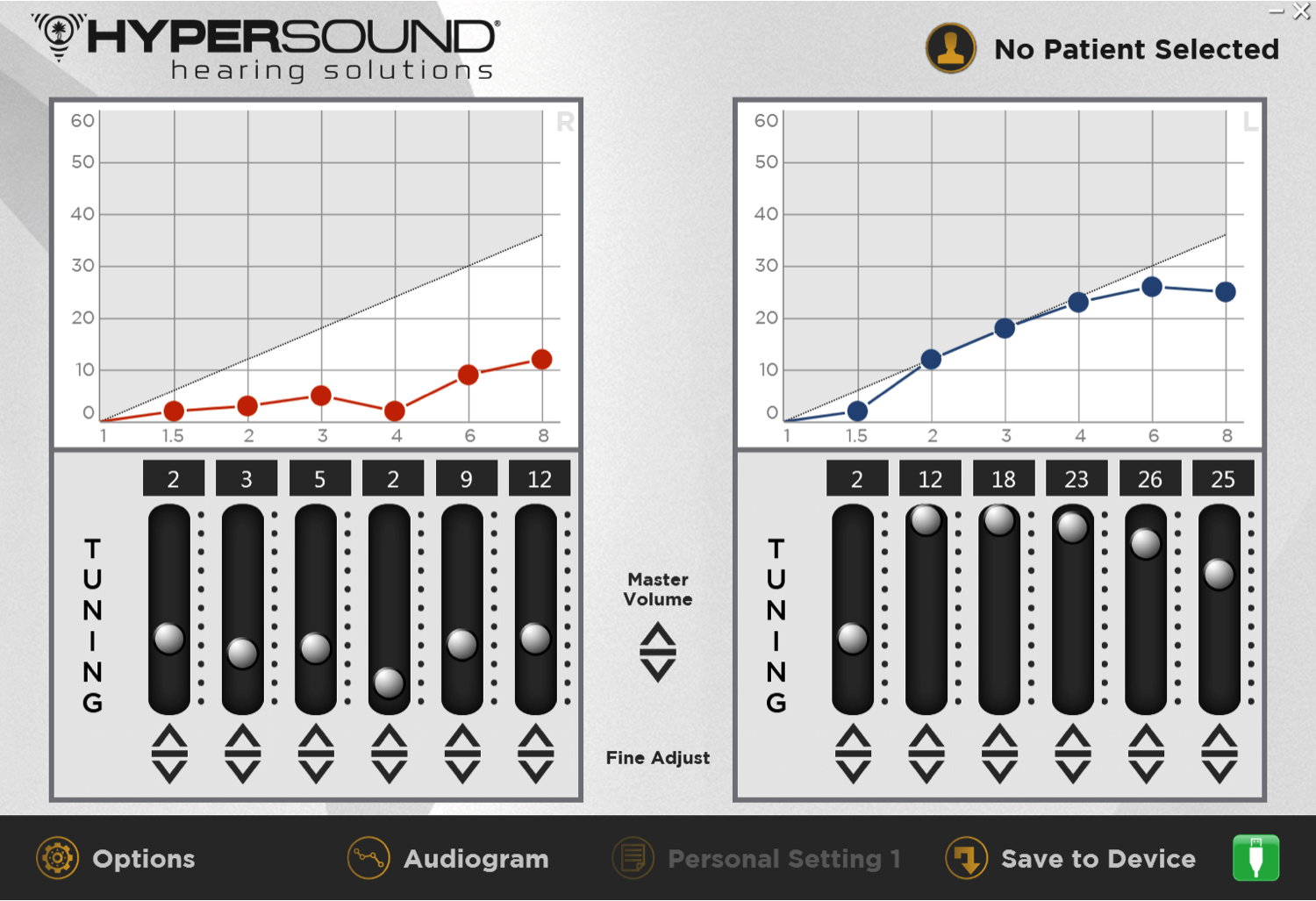

The software is called HyperFit, and you enter the patient’s audiogram. The NAL calculations are made. Figure 3 is a picture of the software with six sliders that allow you to change the gain in the software. You can get up to 30 dB of high-frequency gain. Rather than a hearing aid, you have a left and right emitter or speaker.

Figure 3. HyperSound HyperFit fitting software.

HyperSound is a great way to enhance the patient experience. We think it is a great revenue stream to add to a practice. You can tap into a part of the market that is not ready for hearing aids yet, but eventually over time, it may shorten their decision cycle to purchase hearing aids. If they are hearing the television really well, they may notice more of a problem hearing in other situations. You could think of HyperSound as a gateway product in that regard.

Data

We are beginning to collect data to show the efficacy of HyperSound. I showed you the preference study. We also published a study on AudiologyOnline that compared HyperSound to conventional audio for watching the television (Mehta, Matteson, Seitzman, & Kappus, 2015). We found in this comparative study that HyperSound outperformed the conventional speaker by about 20 to 30%. Ongoing, more rigorous studies are currently underway at four different sites. We hope to publish those over the next one to two years so we have more data to show its effectiveness.

Conclusion

HyperSound is a great product, alternative, or complement to existing technology. It is a great way to tap into some of those parts of the market that do not want or need hearing aids, especially those have mild to moderate hearing losses. We think it can speed the journey to conventional amplification, and in today’s world, a directed audio solution is a great device to add to your product or technology portfolio.

If you want more technical information about HyperSound, you can go to the File Share menu. There is a white paper and spec sheet. You can find more information and details on the HyperSound Channel here on AudiologyOnline.

Questions and Answers

What is the frequency response of HyperSound?

The frequency response with usable gain goes from about 1000 Hz to about 14000 Hz. In the mid range, the gain is between 5 and 15 dB. In around 4000 Hz, the gain maximum is about 30 dB. It relies on the NAL targets as a starting point, but you can use the sliders in your HyperFit software to increase the gain. Also know that there are four different memories. You can store four different programs in HyperSound and use the remote to change them. On the HyperSound, there is a manual wheel, and there is also a remote that allows you to have access to the memories, but also manually adjusts the volume.

How is the sound to other listeners in the room?

Other listeners in the room would hear the regular audio. If you have regular conventional audio on your TV, they would hear that. They would hear a little bit of HyperSound if it reflects off the back wall. However, that is usually not a big effect. If you have a surround sound in your house with the television, they would hear the surround sound. There is no delay associated with the two. The patient is in the HyperSound beam; other members of the family are hearing the audio. I think that is what makes it a really interesting product relative to ALDs.

Can two individuals use one unit?

You can do that with one person per emitter, but you lose a little of the binaural effect. It is really designed for two emitters, one per ear, for one individual. You could possibly do that. If the two people wanted to sit right next to each other, which might not be the best thing, they could benefit from the two emitters. In theory, one system is designed for one individual. You might be able to cut corners a bit if you had two people, but the experience would likely not be the same.

What about the directionality of the device?

It is a very tight beam that comes off of the emitter. The person has to sit in a space about two feet wide, which gives you some leeway. You can move your head a little bit. You do not have to be absolutely still. You do have to keep your head within a two foot beam in order to get the full directional effect. Think of it as a beam of light off of a lighthouse. It is very directed into a certain area. It can reflect off of the back wall, but that is a negligible issue, in my opinion, based on some of the early work we have done.

References

Chai, E., Wang, J., & Rochtchina, E. (2007). Hearing impairment and health-related quality of life: The Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Ear and Hearing, 28, 187-195.

Claesen, E., & Pryce, H. (2012). An exploration of the perspectives of help-seekers prescribed hearing aids. Primary Healthcare, Research and Development, 13(3), 279-284. doi: 10.1017/S1463423611000570

Contrera, K.J., Betz, J., Genther, D.J., & Lin, F.R. (2015). Association of hearing impairment and mortality in the national health and nutrition examination survey. JAMA Otolaryngology -Head & Neck Surgery, 141(10), 944-946. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2015.1762.

Genther, D.J., Frick, K.D., Chen, D., Betz, J. & Lin, F.R. (2013). Association of hearing loss with hospitalization and burden of disease in older adults. JAMA, 309(22), 2322-24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5912

Hannula, S., Bloigu, R., Majamaa, K., Sorri, M., & Maki-Torkko, E. (2011). Self-reported hearing problems among older adults: prevalence and comparison to measured hearing impairment. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 22(8), 550-559. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.22.8.7

Kochkin, S. (2012). MarkeTrak VIII: the key influencing factors in hearing aid purchase intent. Hearing Review, 19(3), 12-25.

Laplante-Lévesque, A., Hickson, L., & Worrall, L. (2012). What makes adults with hearing impairment take up hearing aids or communication programs and achieve successful outcomes? Ear and Hearing, 33(1), 79-93. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822c26dc

Mehta, R. P., Matteson, S. L., Seitzman, R. L., & Kappus, B. (2015, August 30). Speech recognition in the sound field: directed audio vs. conventional speakers. AudiologyOnline, Article 2657. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

Stetler, B. (2012, February 8). Youths are watching, but less often on TV. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/09/business/media/young-people-are-watching-but-less-often-on-tv.html

Tremblay, K. L., Pinto, A., Fischer, M. E., Klein, B. E., Klein, R., Levy, S., et al. (2015). Self-reported hearing difficulties among adults with normal audiograms: The Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Ear and Hearing, 36(6), e290-299. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000195

Cite this Content as:

Taylor, B. (2015, December). Promoting high value, patient-centric care with alternative and complementary devices. AudiologyOnline, Article 16086. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com