Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live seminar. Download supplemental course materials here.

Cindy Beyer: Before we get started, I would like to give you some background information about the topics that we will be covering today. HearUSA owns and operates about 200 hearing clinics across the country. We have standard operating procedures and a best-practices clinical program. We support those through organized training programs in quality oversight. As part of the quality management team, both Suzanne and I have been frontline support for audiologists in a clinical capacity for over 20 years. We will be taking some of those experiences and data that we have collected during our tenure and sharing them with you, in the hopes that it will be of some benefit to your practice.

If we practice long enough, if we see enough patients, especially a diversified caseload that includes the very old and the very young, the chances are high that at some point we are going to experience unexpected and undesirable patient outcomes. The material in this course will give you some insight into clinical errors, provide examples of experiences we have had over the past two decades at HearUSA, and share some lessons that we have learned along the way.

Errors Do Happen

The first rule in medicine is that we do the patient no harm. One of the best ways to minimize risk to our patients is to follow established guidelines that were developed to assist us in delivering conscientious and appropriate care. Scope-of-practice documents are available from the American Academy of Audiology (AAA) and also the American Speech-Language Hearing Association (ASHA). We encourage you to be familiar with those documents and follow some type of established process. Additionally, your practice may wish to write out detailed procedures that facilitate the needs of your particular practice or patient base. A discipline process should be in place, where all of the parties involved in the care process are fully aware, trained, and held accountable. Cultivating an environment of care and consideration is an important part of minimizing clinical errors.

By impromptu survey, it looks like we have a fair amount of people in this live webinar today who indicate that they have experienced an adverse event - something unexpected or undesirable in the course of clinical work. Some of those examples might be an abrasion to the ear canal, an impression that got stuck in the ear and could not be removed, or PE tubes that came out when they were not supposed to.

Liability

Let’s talk about a few things related to audiology and liability. With the privilege of being a health care provider, we have the responsibility of providing care in a competent manner, consistent with the rules of medicine. Some providers might question how greatly malpractice concerns could impact our day-to-day practice. Injuries that occur in our practice are typically minor when compared to those in other medical specialties, especially if we compare ourselves to surgeons. When discussing clinical errors, it may be helpful to view the events in context of health care law.

Malpractice can either be a deliberate or a negligent act that is committed by a health care provider, resulting in injury of other adverse outcome to the patient. Such injury might encompass a broad spectrum of incidences, from a physical injury to the unintentional mismanagement or the misdiagnosis of hearing loss. Malpractice can further be defined by seeing how our delivery of service matches up with an expected standard of care in the community. As an example, the state of Florida (2013) has this definition: “The prevailing professional standard of care for a given health care provider shall be that level of care, skill, and treatment which in light of all relevant surrounding circumstances is recognized as acceptable and appropriate by reasonably prudent, similar health care providers.” This definition is going to vary by state, so you may want to look into your state-specific definition, but the language is likely to be very similar.

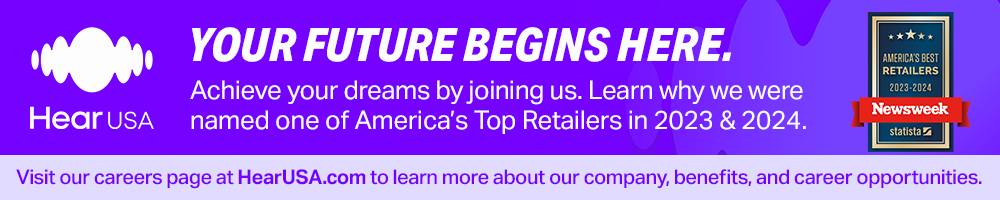

I would like to present some statistics that will help us to see impact of medical errors across the entire medical community (Figure 1). These errors contribute not only to the unfortunate death and injury of hundreds of thousands of people, but they also add another layer of expense to an already inflated healthcare cost structure. The cost of re-treating and rehabilitating due to medically induced problems, in addition to the legal burden of defending the provider, compensating the patient and the legal teams, is staggering. When we evaluate that in the context of the fact that the vast majority of these incidents are preventable, it is worthwhile to be precautionary in our approach.

Figure 1. Statistics of medical errors in the United States.

Why Should We Talk About Errors?

What percentage of adverse outcomes do we believe are preventable? The answer is 70% of medical errors are preventable, with another 5% being potentially preventable.

There are many good reasons why this course is going to be relevant for you. Besides the fact that some states require the course for continuing education, a number of you reported that you have experienced an adverse incident. Maybe a patient filed a suit against you; perhaps you felt the regret or discomfort that comes from a bleeding ear or a crying child. Comparatively speaking, audiology is low risk, but we live in an ever-increasing litigious environment, and we need to be aware of the risks and consequences.

As health care advances, the complexities of diagnosing and treating medical problems is also going to increase. Millions of dollars are spent in resolving cases of medical liability. Regulatory agencies continue to impose more and more responsibility on us as licensed providers, so it is in our best interest and that of our patients to know the guidelines; it is the right thing to do.

This course has been developed to identify some of the areas in hearing care practice that could lead to clinical error. Our hope is that the probability of these errors occurring in our practice will decrease as we bring some of the areas to light. We will talk about infection control, history and documentation, cerumen removal, evaluation and testing, ear mold impressions, hearing aid circuitry and programming errors, verification errors, and electrophysiologic errors.

Infection Control

In the delivery in any health care service, it is the provider’s responsibility to ensure the safety of all the patients served. It is imperative that audiologists provide their patients with testing and treatment environments that control for the transmission of disease from clinician to patient, patient to clinician and from patient to patient. Elderly patients and newborns and small children may present with compromised immune systems, which places them at particular risk for infection. Direct contact occurs not only between the clinician and the patient, but also between the patient and the equipment, and the tools that, in turn, come in contact with other patients. Following an established infection control protocol is especially important when the potential for contact with bodily fluid exists. Bankaitis and Kemp (2003; 2005) have published books that are excellent. If you do not have an active infection control program in your practice, now would be a good time to look at that.

What is the greatest potential source for spreading infection? Most of you know that it is unwashed hands. In addition to the lack of hand washing, you are going to see other scenarios that unfold. My pet peeve is the handling of unclean hearing aids. When a patient comes into our office, they hand us a dirty hearing aid, and we instinctively reach out to receive it. In our centers, the hearing aid should always be delivered into a container. We use a small Dixie cup or sanitizing wipe. We clean it before we handle it with our bare hands. This way we will protect ourselves from the transmission of bacteria.

The next common error is failure to disinfect patient contact areas. This would be every counter, chair or surface that is touched by the patient. That should be done after every encounter. Ultrasonic solution should be changed after every cleansing. Another error is failure to clean and disinfect tools. Again, anything that has touched a patient or bodily fluid must be properly cleaned or disposed. Reusing the foam or disposable tips or not cleaning the tips or the real-ear measurement tubing between patients is unacceptable. Neglecting to wash hands after handling the tools and equipment or improper storage of clean and dirty tympanometry tips are other common errors. The dirty tips are usually stored in the disinfectant solution, but even clean ones need to be stored within a covered container. You might want to consider using posters or signs around the office to remind co-workers of this responsibility, and if you see someone who is non-complaint, offer a friendly reminder. Policing the environment and helping each other to stay diligent about that is very helpful.

Medical Records and Record Keeping

Let’s talk about medical records. In my experience, the maintenance of clinical records is the single biggest area for performance improvements. This could be likely same for all licensed health care providers. It is really impossible to develop an effective plan of care without first evaluating each patient’s medical and audiological history. It is by asking the right questions that we are in a position to determine the right direction of care. It is important that we explore every question in the case history and document those answers into the record. This takes time, but it saves time and inconvenience in the future, especially if the file is going to be transferring to a different provider. As a side note, HearUSA has experienced many audits from insurers, third parties and Medicaid investigators, and the extent and the quality of the documentation in the file plays a very important role in how they assess us.

Good record keeping also helps us to stay focused and develop logical plans for patient care. Again, it is time-consuming, but there are good reasons for taking the time to record the results of every contact and every visit with the patient. Primarily, we want to have that information available when we review the file and make decisions. Secondly, those records are legal documents, and all of those documents are also subject to subpoena and other types of regulatory review. Our professional names and license numbers are attached to those records. People and institutions will make judgments and opinions about us according to that documentation. Let’s make sure that our work is represented well. Remember that we are best served when we take good notes.

Another tip is to keep records of the exact hearing aid make, model, circuitry features, and experiences of the previous hearing aid user. Any recommendations that we make for improvement should incorporate those past experiences as well as the current and future expectations. We gain a lot of insight from knowing the details of previous fittings when we start with our go-forward plan. If medical clearance is indicated by the result of the test, it is important that we make a reasonable effort to obtain it. Although the patient may sign the waiver, we should still ask for the clearance if it is appropriate to do so. A detailed review of the history and patient experiences, along with our plan to meet that particular patient’s expectations, will guide us in the right direction. I would like to note that if you do have a challenging patient who has been seen on repeated occasion, and they have been unsuccessful with treatment, you may want to consider asking a colleague for assistance to make sure that you are trying to address those unresolved problems. It leads to frustration and failure for both the patient and the provider. Ask for help sooner rather than later, and then document all of those steps that were taken so they will be available for future reference.

The American Medical Association (AMA) has set forth guidelines for record keeping. Every visit should include a relevant history, the physical examination findings, any prior test results, the results of your assessment, your clinical impressions, your diagnosis, the rationale for ordering additional tests or services, the patient’s progress notes, the response to any changes in your treatment plan, any revision of the diagnosis and details of your care plan. Every one of your entries should be dated and have a legible identity of the particular provider, which can be a signature, initials or electronic signature – whatever is required to authenticate the record.

Common deficiencies in medical records include incomplete or illegible notes, encounter forms or flow sheets, missing or illegible signatures, or any changes that are made to the original medical record. These can be problematic for many of us. Remember that you cannot erase or white-out anything in the medical record. Be aware that not all medical practitioners, particularly support staff, are aware of what non-standard medical abbreviations we might use. We have had situations where the AS/AD and the > and < symbols are not understood. We want to avoid any type of biased or nonprofessional remarks.

Having disorganized files is a problem. You may want to use the multipart charts to help organize your paper files, particularly if you have had the patient for a long time. Making any nonprofessional or sarcastic remarks in to the file, repetitive or non-individualized notes, especially with electronic medical records, is something that is frowned upon, as is the misuse of rubber stamps or electronic signatures.

Documentation

Documentation is an area where most people can use some improvement. Common errors include failure to document all the patient visits, failure to sign them, failure to include both subjective and objective data at each visit, failure to document actions and follow-up, failure to include the hearing aid experiences, and insufficient history and documentation of needs and patient expectations. Some that are very specific to our field are not saving hearing aid programming changes, not printing them or having them available for future reference, and missing physician scripts and signed clearance forms. If we are dealing in cases of Medicare and Medicaid billing, remember that medical necessity is established specifically by a physician script. If it is missing, then the file is not represented well, and medical necessity has not been established. Other areas include failure to ensure that all of the required language for the state dispensing boards is on the patients’ purchase agreements, not following the patient care adequately, and again, not resolving all of the issues that the patient may have.

HearUSA has been involved with several civil court cases pertaining to hearing aid sales. In these scenarios, there is an arbitrator or court representative, and the provider must be presented with the plaintiff in order to try to achieve some type of an agreeable outcome. Be forewarned that the court does not want to go through a lot of verbal “he said/she said.” The key here is professional documentation that completely covers the situation. It can make or break the outcome. Sometimes you are called to court several months or over a year after the incident occurs. Your memory will not serve you well, but good documentation will. Keep that in mind as you move forward.

Similarly, we have seen dozens of cases where consumers file action with the state licensing boards. The process entails a written response first from the licensee with supporting documentation. Again, if it is not written down, it did not happen. The time to incorporate this record keeping system is before the problem happens, not after. I recall that a well-experienced audiologist received a complaint from the state alleging that she did not offer a repair to a hearing aid patient. The patient had asked about repairing their hearing aid. The audiologist apparently did not attempt to repair it, and she advised that the patient either pursue a factory repair or a new hearing aid. None of this was documented in the patient file. The patient went to another provider who was able to repair the hearing aid in the office. I do not recall the specific issue, but the patient’s perception was that the provider deceptively refused to repair the hearing aid in the office and tried to extort money from him. There was nothing available in the file to assist the audiologist in her defense. She had to do it from memory.

We have observed several similar types of investigations in the past where allegations were made that the wrong hearing aid was recommended or there was a misdiagnosis. To my knowledge, none of these cases ever resulted in board disciplinary action, but the thing is that they take time and resources to respond to the complaint, and the experience is not without some cost in professional dignity.

By way of reminder, if we are not able to acquire medical clearance, make sure that you document that you have asked for it and that the patient understands that. Do not leave your unresolved issues hanging. An example of this would be if your note said, “The patient is unhappy with hearing aids,” but did not go on to say what the proposed action would be to take care of that, or, “The hearing aid is dead,” with no resulting follow-up about how it is going to be fixed. We recommend in our centers and practices that there is always a next appointment to be scheduled, and there is always a next step that is identified in the medical record, whether that be a two-week, six-month or annual follow-up. It should be indicated in the file.

Binaural waivers are used when patients choose a monaural fitting when a binaural fitting was recommended. I am not aware of many cases where litigation ensued as a result of a monaural fitting when a binaural fitting was appropriate, but there may be some precautionary value to using the waiver. Many audiologists feel that it is challenging to ask the patient to use a binaural waiver, so I do not think that it is commonly in use, but it is an option that is available.

Cerumen Removal

This is an area of practice which does present the possibility of error because it is invasive to the ear. Approximately 150,000 ears are cleaned every week in the United States. In most cases, ear wax removal is a prerequisite to hearing practices, unless it is prohibited by your state. Excess cerumen can interfere with the hearing test, the audiology exam, the ear mold impressions, the probe-mic measures, and also hearing aid function. In most states, only physicians, nurses or audiologists who have been trained in cerumen removal can perform that. Some states prohibit audiologists from removing wax or remain silent on the issue, so you will want to know your state’s licensure laws. If it is not recognized by your board in your scope of practice, your liability insurance might not cover it. Check into that if you are performing cerumen removal. You want to make sure that anyone in your practice has the proper training. It does take some skill, even with training. There are other requirements such as good vision and good dexterity. You are going to need to have the right tools and equipment and a very stable, effective light source to safely remove cerumen.

There are some contraindications for cerumen removal. Any type of ear disease or effusion within the ear, hematomas, surgically-modified ear canals, foreign bodies in the ear canal, patients who are diabetic, have suppressed immune systems or bleeding disorders are all cases where we suggest that it is not a good idea to pursue cerumen management. Other cases to strongly reconsider are those where you know the patient has some type of pending legal proceeding, or if the patient needs to be restrained to be able to remove the wax.

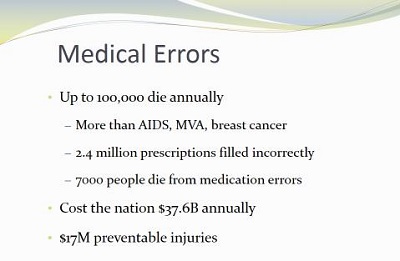

One of the most common errors in cerumen removal is ignoring contraindications. We suggest using a cerumen consent form that identifies what the process is to remove wax and what those contraindications are. Not having signatures on those forms is something that we constantly remind our centers about. Other than that, not cleaning the tools, not storing the tools properly, or slight canal abrasions are things that could happen during the course of cerumen removal. Figure 2 shows pictures of what can happen in the process of removing cerumen if there is some type of injury to the ear canal.

Figure 2. Subdermal hematomas following cerumen removal.

Common Errors in Audiometry

The following are audiometrical errors that we have observed over the years: incomplete or poor case histories, improper supervision of students, choosing the wrong test or omitting a test due to time constraints, over or under masking, interpretation errors, not making a referral when it is appropriate to do so, or not keeping children or difficult-to-test patients on task and getting invalid results. Remember that when you supervise students, they are under your name and license, which makes their results and reports your responsibility.

Other common testing errors are improper placement of the headphones or the bone oscillator, poor or unclear test instructions to the patient, false-positive air-bone gaps that are related to the insert receiver positioning, speech recognition testing at levels that are too low to reach maximum performance, failure to perform annual calibrations, and not performing the daily or the weekly listening checks.

To avoid errors, we need to control even the most routine aspects of audiology. It is often the sheer repetitiveness of the procedure that can lead us to negligence. Such is the case with threshold testing. Even something as simple as reversing the ear phones cannot only alter the diagnosis, but lead to erroneous recommendations for the patient.

If the patient is not clear about the directions for the test, we can get false-positive or false-negative results. Make sure that you double-check your results and that everything adds up. Clear up any obvious discrepancies. For example, if you have a Type B tympanogram with present acoustic reflexes and no air bone gaps, there could be a problem with some aspect of the test. Similarly, if the speech scores do not support the air-conduction thresholds, additional work is necessary to clear up any uncertainties there. It is our job to rule out discrepancies and things such as air-bone gaps that could be related to improper insertion of the receivers or even collapsed ear canals.

Hearing Aid Assessments

Hearing aid dispensing is regulated through our state boards; each state has required testing and prerequisites that will be detailed in their rules. At a minimum, it usually is going to be speech audiometry and air- and bone-conduction testing. They almost always require some type of tolerance and comfort levels. Some states go beyond that and require things such as sound booths. Some states unfortunately do not have that requirement, but they may have other specific testing or text requirements as we mentioned before. I believe there are some states that require real-ear measurements for example. It is important that you do know what your state requirements are.

Masking is something that can be difficult for some audiologists, and certainly something that takes experience to do well. Inaccurate masking can lead to inappropriate recommendations, improper referrals and inadequate hearing aid fittings. It is worthwhile to point out to hearing aid dispensers that masking is typically involved with diagnostic testing. In cases where there are potential medical problems for audiology assessment, it is important that they be referred since the hearing aid dispenser’s scope of practice is limited to testing for the purposes of fitting hearing aids.

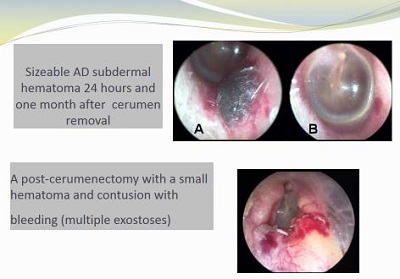

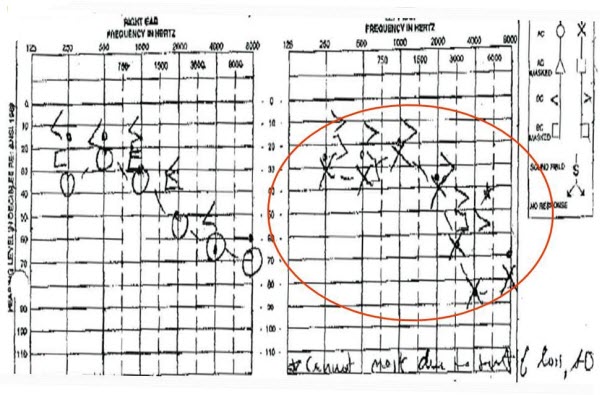

Suzanne Younker: Figure 3 is an example of two audiograms from the same patient –one from 2006 and then again in 2010. If we look at the 2006 audiogram at 500 Hz for masking going into the right ear to test bone conduction for the left ear, the bone conduction threshold was obtained at 65 dB using 65 dB of masking. The arrow shown in Figure 3 shifted during the presentation; it is 60 dB. Four years later when the same patient is retested, the bone-conduction threshold got better. How does that happen? They only used 55 dB of masking; the air-conduction threshold had shifted, so theoretically you would have wanted more masking. This is a case of insufficient masking, which is an error.

Figure 3. Case of under masking, which is a clinical error.

Medical Referrals

Cindy Beyer: Let’s talk about medical referrals. The coordination of care between you and the patient’s physician is going to ensure that the patient receives appropriate treatment for the condition. To do this, it is important that we have standardized, established practice guidelines to avoid the over- and under-referring of medical care. Under-referring patients for a physician intervention can deny patients the opportunity for the most effective resolution to their condition. Over-referring patients for medical care is both costly and is inconvenient. The answer to that is in following established standardized guidelines. This way, we provide a good basis for coordination of care. As a side note, the presence of artificial air-bone gaps is something that is a primary source of over-referral, which goes back to our earlier discussion about making sure that we tie together our test results.

Ear Impressions

In our experience, the taking of ear impressions is by far the riskiest procedure that we perform. With proper training and experience, impressions can be performed very safely. It is clearly an integral part of our everyday practice. However, we do need to be diligent because this procedure is invasive, and there can be serious, unforeseen complications. When we see a deep, aggressive ear canal impression, it calls into question the procedure that was used to obtain it. The potential for damage to outer, middle, and even inner ear structures increases when we take deep canal ear impressions. Complications can include minor abrasions to the canal, trauma lesions to the tympanic membrane and the ossicles, the accidental removal of a PE tube, perilymph fistula with fluctuating progressive or longstanding sensorineural hearing loss, or concussive inner ear trauma accompanied by temporary or even permanent threshold shifts.

To minimize the risk associated with ear impressions, we need careful procedures and examination of the ear. When we place the otoscope within the ear, use a bracing technique to avoid potential injury to the canal wall or to the tympanic membrane. This is very important when working with young children, patients that might be nervous or frightened by the process, or anyone that has compromised neuromuscular control. It is also important to visualize the ear canal pre- and post-block placement, making sure that there are not any gaps between the wall and the block.

In 2012, HearUSA documented 14 incidents that were related to ear impressions. In the context of the tens of thousands of ear impressions that we take in a year, that is a very small amount. However, it is quite significant because it is the most adverse of outcome situations that we have. The most frequent things that we see are abrasions and embedded ear molds that we cannot remove from the ear canal. The vast majority of these are going to be resolved without any legal or liability. But over the years, we have had some challenging cases, and we are going to take you through a few of them that are most memorable.

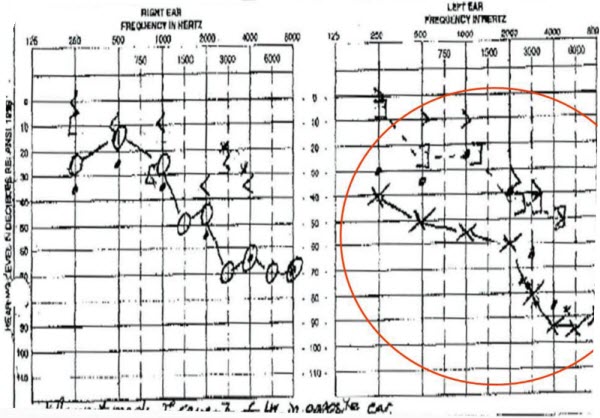

Figure 4 shows the audiogram of a 68-year-old female before an ear impression was taken. After the left-ear impression, there was reported pain and bleeding and the patient did seek an ear, nose and throat (ENT) consultation regarding this case. We found out what the physician findings were, because we got a report from our insurance company after the patient filed suit against us. This was many years ago, but the notes the surgeon provided indicated the patient was left with numbness in the tongue, a loss of taste, additional hearing loss and also dizziness. Impression material was scraped from the tympanic membrane under general anesthesia. This case was settled out of court for $100,000. Figure 5 is what the audiogram looked like post impression. You will see that there was a significant decrease in the hearing ability. I think it is also worth mentioning that the impression material at the time that the physician closed the case remained imbedded in the ossicles, as the doctor felt that it would cause more structural damage to remove it than to leave it there.

Figure 4. Audiogram from a 68-year-old female prior to ear impressions.

Figure 5. Audiogram from the same 68-year-old patient after left-ear impression, now showing mixed hearing loss.

The next case we will present is a blow by (Figure 6). It is an extreme case that happened several years ago. The patient came in with a moderate to severe sensorineural hearing loss in the incident ear and a severe hearing loss in the other ear. I do not have copies of the audiogram, but neither the audiologist, the general practitioner, nor the ENT could remove the impression, and it caused severe pain every time they tried to take it out of the ear.

Figure 6. Example of a blow-by impression, where the material moves past the block.

Eventually the patient had to be sedated, and it was surgically removed. At the time that the patient underwent the procedure, the material had obliterated the tympanic membrane, surrounded the ossicles, and even entered the Eustachian tube. The patient had to have surgery to repair the tympanic membrane and remove an ossicle. Subsequently, they had to replace the ossicle and clean out the Eustachian tube in an attempt to restore hearing. The patient had a significant decrease in the air-conduction thresholds; note that this was the patient’s better ear. The patient now presents with severe to profound hearing loss and also complain of dizziness. This case was settled for $560,000. When these things happen, the audiologist who is involved has to be reported to one of the national data banks that track malpractice suits. HearUSA went through an extensive process where we developed corrective actions and demonstrated training and education programs within our company.

Our next case is less serious, but still something we thought was worth mentioning. We know of at least a half-dozen cases where PE tubes have been dislodged during the course of impressions with children. Most of these happen when making swim molds. In these cases, the child often experiences significant pain to the ear with bleeding, and the parent is going to be very distressed. Of course, the physician is not pleased that this surgical process has resulted in an ineffective situation. There is never a good end result in this case. It is worthwhile for us to consider that making impressions in children with PE tubes is an ongoing risk for us.

One audiologist, who was very experienced, said that she did not see a gap between the cotton block and the ear canal, and the material blew right past the block. It was a small child and the gap was very small. She had been doing impressions for 25 years. Her regret is that she should have looked more carefully, but she just did not see the gap. This is something that could happen to anyone, but we need to be careful and take precautions that we are not letting it happen to us. We share this lesson because we have to be diligent, never take our skills for granted, never rush, always visualize the block placement with very good lighting, and incorporate the patient history with what you observe and take any steps necessary to avoid this problem.

If the ear canal is oddly shaped or has been surgically modified, take extra caution. Digital scanning of the ears is a future practice that we can look forward to. If we could digitally scan the topography of the ear, it would remove this risk and would certainly be a welcome tool that we would have at our disposal.

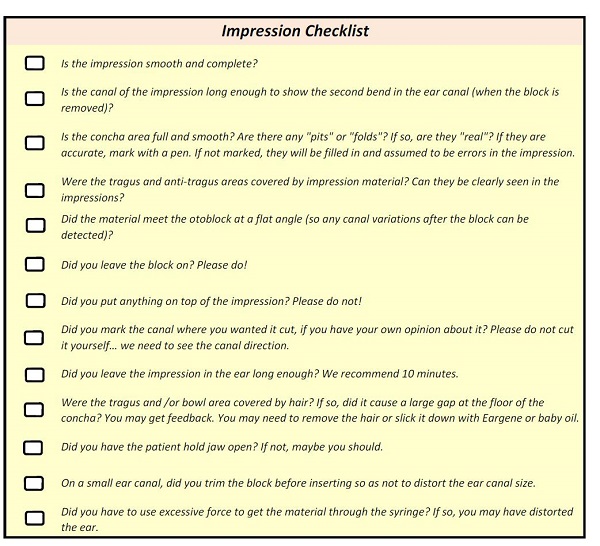

Figure 7 is our impression checklist. We train with this; we do corrective action with this. We have this available for all our clinicians to use.

Figure 7. Impression checklist.

Technology and Programming Errors

With the development of digital hearing aids, audiologists and patients alike were introduced to a new world of flexibility and possibilities. With these benefits came the added complexity of multiple memories, processing algorithms and the continuously evolving automatic features that new hearing aids have. Undeniably, digital hearing aids are a tremendous advantage for a number of reasons. That is not to say, however, that digital amplification in and of itself will automatically result in an improved patient outcome. It is still incumbent upon us to employ the skills and techniques that will result in the patient realizing those benefits.

One of the most common mistakes in hearing aid dispensing is the over-reliance on first-fit algorithms. An online survey a few years ago (Mueller, Bentler, & Wu, 2008) showed that 70% of the audiologists were programming their patients hearing aids using the first-fit setting. Furthermore, less than 12% of the targets on the manufacturer’s software screen were measured in the patient’s ear. There was not a very good correlation there. Software varies considerably between the manufacturers, and we cannot assume that the norms there are going to apply to each individual patient in our offices. We have to verify the fitting objectively with probe-microphone measurements and then subjectively assess the patient’s results, using all of that data to make an expert decision on the patient’s behalf.

Using first fits as a routine procedure often leads to repeat visits, unrealized expectations and anxiety on the part of the patient. It is also a waste of your time to keep adjusting and counseling patients in the absence of a good clinical fix. I will note that manufacturers are better today and there could be more correct fittings the first time, but it is still our responsibility to make sure that that is the case. Do not assume anything until you have verified a fitting.

Other areas of potential fit fails are neglecting to take into consideration the previous amplification experiences and failure to identify the patient’s primary needs and expectations. These both have a significant influence on the technology that we select as well as the way in which we are going to apply those technologies. The best way to make the most of advancements and give our patients the best features is through a disciplined process of evaluating both pre- and post-hearing-aid fittings, analyzing that data, along with a healthy investment in patient education and counseling.

In our experience, some of the most common hearing aid dispensing errors include not saving the program into the hearing aid, handing back factory repairs that were not programmed appropriately, using inappropriate compression strategies, not ordering the appropriate circuitry options, not activating or fully programming the additional memories, not incorporating the past history into the programming logic, over-relying on first-fit algorithms, and not entering bone-conduction threholds when there is an air-bone gap.

I recall one case of a fitting complication that we had several years ago. The patient wanted to wear completely-in-the canal (CIC) hearing aids. We had a very experienced audiologist who wanted to accommodate that patient, but the patient had a longstanding perforation in the eardrum and also had diabetes. Within 90 days of receiving the CIC hearing aids, the patient had a raging fungus in the ear. With the closing of the ear canal with no venting and the diabetic predisposition to fungus, the case turned very nasty. It took dozens of doctor visits and refitting to a behind-the-ear (BTE) hearing aid over an 8-month period to resolve that issue. There was also some restitution that had to be made to the patient. How could we have altered that course?

Some audiologists may have refused to fit the CIC hearing aids, but at the very least, the patient needed to have rigorous training on the importance of ventilating the ear, how to thoroughly clean the hearing aid, and perhaps have had a wearing schedule. According to the patient, this did not occur, and there was unfortunately no supporting documentation in the patient file that would speak to that type of a regimen. We were left to deal with the circumstances as they were. If you are pursuing a risky fit, take care to implement and document specific precautionary measures.

Verification and Validation

Verification and validation are clinical tools that ensure the functionality of the hearing aids as well as the individual patient benefit. Verification techniques are primarily used to determine if the hearing aids meet a particular standard. Validation techniques, such as functional gain, speech perception questionnaires or interviews, are used so that we can determine how much benefit is perceived from using the hearing aids. One method is objective - the measurement. One method is subjective - patient feedback. However, the literature suggests that neither validation nor verification are typically used by clinicians, even though they have been found to be highly correlated with user satisfaction (Mueller, et al., 2008).

We can look to the MarkeTrak data. MarkeTrak VIII (Kochkin, 2012) had some very explicit data about this. Studies there concluded that verification and validation during the hearing aid fitting process was shown to significantly reduce patient visits, with evidence that using both of them together would yield the best results. MarkeTrak VIII did suggest that wide scale adoption of verification and validation would improve patient satisfaction and reduce patient visits by more than half a million. That is very impressive data.

Verification

The biggest mistake that most audiologists make is the failure to verify fittings. According to the online survey (Mueller, et al., 2008), up to 80% of the providers do not rely on verification. Rather, they rely exclusively on patient feedback to make their adjustments. If we restate that, this could be considered gross negligence, and it can contribute to the lack of professionalism that is perceived by the consumer. Think about it. It delegates the responsibility for the course of care to the patient, because the patient would be directing us and guiding us as to what needs to be done to optimize their fitting. That is something that many of us feel is a very big responsibility of the field; it is something that we do not feel we can overstate. Be reminded that in the practice of health care, pre and post measurement of the condition is a universally accepted practice.

Probe-microphone Measurement

First and foremost, we need to do probe-mic measurements. Secondly, we need to hold ourselves to a standard to ensure that we use soft, medium, and loud inputs so that we can yield acceptable outputs within the patient’s dynamic range. Our goal is to provide audibility, maximize speech intelligibility and maintain a zone of comfort for the patient. When we have a restricted dynamic range, it results in distortion and can also result in under-amplification for the patient.

Patients who purchase multi-memory products have an expectation that a specific functionality is going to be present. When they activate that secondary program, they are looking for a response that matches their expectation of what we told them was going to happen. When that does not occur, it could be that the program is defective, was not saved into the memory, or that the program is not functioning as we intended. In any event, it is our obligation to measure and demonstrate that the hearing aid is functioning and doing what we told the patient that it would do, not only in one setting, but in multiple settings. This also provides an opportunity to give additional training to the patient as indicated by what we measure the hearing aid to be doing. This is also true with directional microphones. Do they work like we think they are supposed to? It is something that we want to think about.

Common errors that we see with hearing aid verification are not verifying the settings, not verifying the programs, not interpreting the output appropriately, not including bone conduction in the real-ear target, which will predict a higher gain target if the software recognizes a conductive component, and not using the speech signals for digital products.

Validation

One of the most common deficiency with validation is the failure to use a standardized measure. Many practitioners use subjective comments from the patient to get their feedback. If you use a standardized measure, you will have an organized process and will consistently offer every patient the same opportunity to provide feedback in a very structured way. We need to use standardized measures for patient feedback. We need to write them down and not use off-hand remarks.

Then, we need to analyze that data. If you can aggregate data within your practice, you will be surprised what you will find. You will see areas of performance that need improvement. You can notify yourself and your colleagues of deficiencies or weaknesses within your process. That data can be valuable to help you improve clinical performance and elevate your overall standard of care.

I will turn the program over to Dr. Younker at this point.

Pediatric Fittings, ENG/VNG and ABR

Suzanne Younker: We are going to discuss the topics of pediatric fittings, videonystagmography (VNG) and auditory brainstem response (ABR). We did want to take into account pediatric considerations.

We understand that in audiology, we are dealing with patients who are different ages and of different cognitive levels. Audiologists must be skilled in testing young children and have the social skills to also work with the parents of those children. They also need to be able to be flexible and recognize at any moment if the current testing procedure is not quite effective, and they need to change it. There is a lot of clinical judgment that comes into play when testing children, specifically infants and young children. Second opinions from a trusted colleague are helpful, especially if we are dealing with multiple-handicapped children or those with reduced cognitive function. These special populations require an even greater level of assistance, knowledge, skills and experience.

There are times when we may not have all the results that we need when we are fitting hearing instruments to children; sometimes we have to fit on the fly or use a hearing instrument that is extremely flexible with a lot of features. We know that we are going to be constantly assessing these children to fill in the diagnostic gaps over time in order to give them the best fit. It is a process.

Perspective from a Seasoned Audiologist

When preparing for this lecture, I polled some of our seasoned audiologists and externs alike about what they thought was something that should be mentioned during a medical errors course. I find that I almost prefer in some situations to have an extern provide some services over a seasoned audiologist because, frankly, externs are very keen on wanting to do the right thing every time. They have an attitude of being new at something and wanting the help and guidance, whereas some seasoned audiologists have an attitude of routine, where they are not as hyperaware of their actions. The extern tends to follow directions extremely well, perform step-by-step procedures and they do not let their egos get in the way.

I obtained the pediatric-behavioral-test perspective from a 16-year audiologist who believes that an incomplete test is considered an error. As you know, when working with children, that can happen, but if you are extremely skilled that should be not happening as frequently. Telling a parent to come back to complete a test because the child is fatigued is frustrating. When you have not gathered all the data, you are not able to appropriately recommend or treat that patient. Delaying results and recommendations should be limited as much as possible in all cases.

That same veteran audiologist said that it is easy to misdiagnose a response when, in fact, the child’s reaction was a behavioral response to a non-hearing related issue. Again, an experienced pediatric audiologist would know that. This particular audiologist said she finds if she observes the patient in the waiting room before she takes them back, it helps to better understand the developmental capabilities of that child so she knows where to begin her test. That is an excellent tool. This audiologist uses her iPhone as her greatest tool when testing otoacoustic emissions (OAEs). There are free apps to entertain the kids, which keeps artifact and noise to a minimum.

The energy level and praise from a pediatric audiologist is extremely important. You have to get silly and be able to make faces. You have to have an outgoing personality with children. She said, “When I see a child with attention issues starting to fatigue, I often have them come out of the booth and do jumping jacks to get them going again.” Those are excellent tips.

In this audiologist’s mind, parents can cause errors when we go to testing. Parents are excited; they want their child to perform well. Sometimes when audiologists are working independently, they have to ask for the caregiver to help, particularly with play or visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA) in the sound booth. Parents do have a natural tendency to coach their child into giving a response that is not accurate. Giving that parent very clear instructions on what to do and avoid before entering the booth is imperative to prevent false positives or false negatives.

When performing ABR with newborns, the parent is in the room. It is good to keep the environment and mood relaxed. New mothers are very stressed and sleep deprived. This audiologist that I polled said, “I find that when I put them at ease from the beginning, I have a greater chance of not obtaining inconclusive results.” Putting the parents at ease from the beginning can be instrumental in obtaining accurate results. Certainly, that is something that we prefer to do at every moment. In addition, this audiologist said, “I always troubleshoot my equipment when I see questionable results.” Without alarming the parent, make sure a stimulus is being presented from the transducer. Sometimes electrodes slip or the inserts fall out of the ear, and in a very nonchalant manner, make sure the equipment is functioning optimally, like it is a standard course of action.”

This same audiologist’s counseling policy is to provide adequate counseling with hearing aids in pediatrics; otherwise, it could be considered an error. She stated, “It is important to inform the parents that this is a process.” We know that parents can be nervous and that they want all of the knowledge at once. We know that sometimes that is not possible in one day, but if we advise them that the hearing testing is a process and that we are with them every step of the way, it may put them at ease. She explains that often, it is a puzzle, and you fill in the pieces as you go. We should give the expectation that continuous monitoring of that child will be required. Appropriate and adequate counseling is necessary to avoid the errors of the parent not following directions or being noncompliant with the course of testing or treatment.

On the day of the first fitting, it is important the parent does not expect a very young child to respond to his or her name when the hearing aids are turned on. They are not going to respond to their name right away. The initial goals are to keep the hearing aids in the ears and have the parent keep journals of sound awareness. The child and the parents should be enrolled or referred to all the proper agencies that will assist them to maximize success.

Certainly, not providing a child with proper motivation can be an error. This is a big issue when you are fitting adolescents and teenagers. They are going to feel some peer pressure about wearing their hearing aids, and if we do not do our job to motivate them to wear their hearing aids, it is an error on our part. Parents face many battles. Getting children to wear their hearing aids is one of those battles. She goes on to state, “I try to make their job easier. I always direct the counseling presentation to both the parent and the child if old enough. For children who are old enough, I encourage parents to let [the child] choose their color. It is hard enough to get the kids to wear their hearing aids due to peer pressure.” This audiologist also gets the teenagers and adolescents excited by showing them that they are capable of having their music and cell phones streamed right through their hearing aids. That is a fabulous motivator for tech-savvy adolescents who wear hearing aids.

To wrap up working with children and pediatrics, I want to discuss hearing aids and motivation. The biggest challenge with older children is getting them to continue with the process that is recommended. This seasoned audiologist remarked, “I ask older children how much they think their hearing aids cost. Most of them have no idea. I tell them the cost, even if insurance benefits were used to pay for [them].” She is giving the value and making it a tangible issue for the child to understand. “After they understand the value of the hearing aids, they tend to take better care of them. I always feel the parent appreciates their child hearing it from a professional.” She adds her personal testimony, “I know I can tell my son to wear his head gear at night, but until the orthodontist reinforces it, there is no value in it.”

As pediatric audiologists, it is our job to assure these children are compliant and understand the value of the hearing aids to their life.

Vestibular Reminders and Cautions

There are always some basic reminders and precautions that we want to have in the back of our minds when we are doing vestibular tests. There are some pretest instructions for vestibular testing, such as having the patient limit or omit foods and medications prior to the test. In our clinic, we send out letters ahead of time confirming their appointment with a list of do’s and don’ts and what to expect. One example is having someone drive you to the appointment because you might not feel well afterward. This prepares them ahead of time.

Obtain a thorough medical history. We should also assess the medications that affect vestibular responses. Take note of what those effects are on our balance and vestibular system. It gives you an idea of what to expect on the test results if the patient is on these medications and cannot be taken off them. Document what medications they have taken on the day of the test.

We have the responsibility to be the best we can be with each and every vestibular test. As I mentioned earlier, the seasoned audiologist sometimes falls into a routine and has a nonchalant methodology. Again, an extern who is very hypersensitive to their actions will want to do everything right and can often be very careful and perform extremely well on these tests. Our behavior and attitude affect how we treat our patients. Does that affect how we administer the directions to our patients? This VNG might be your 100th, but it is probably the patient’s first. Try to keep in mind that this patient is assuming that you believe that everything is extremely special and first for them. It is important to put your patient at ease and assure that you are doing everything you can.

Tasking is an area where I find this to be mostly true. We get in the habit of giving the same tasks - count backwards from 10, count backwards from 100 by 10s, count backwards by 2s, give me a name for every letter of the alphabet, et cetera. Those are very standard types of tasking methods, but if they are not of interest to that patient or you have not identified what triggers that patient to concentrate on you, you might not get the result that you need during your vestibular testing.

Another professional behavior error is under-referring for vestibular rehabilitation therapy or to ancillary health care providers. Maybe you are not performing the therapy, but maybe you are. We would refer to the patient’s primary care physician and suggest physical therapy. That is a great alternative if the results warrant that type of treatment.

There are other patient behaviors that we need to consider. Obviously they are going to be anxious and nervous. Do they have neck or back injuries or visual impairments? Sometimes a patient does not have vision in one eye, and you have to make necessary adjustments for that during a VNG test. Consider if they have a hearing loss or cognitive difficulties. If they cannot hear or understand your instructions for the tasking, they might not be able to do what is required to produce the results that you need. Consider both your physical stature and the stature of your patient. I am short. If I am putting a larger patient in a physical position, I have to be aware of how I am going to do that most effectively. Can you put a patient in a Dix-Hallpike maneuver comfortably, safely and accurately? Their size in relation to yours must be taken into account. For older patients, we need to be aware that they might have an osteoporosis “hump.” Know that you might not be able to put them in ideal positions; you have to change to a modified position to get your results.

Another vestibular reminder is about vestibular rehabilitation, which is certainly within our scope of practice. Some audiologists do this in the clinic. If you do, make sure that you are addressing the appropriate pathology before you administer the techniques. In your vestibular findings, you would know if you have identified a posterior, anterior or horizontal canal lithiasis, which would warrant some type of maneuvering positional therapy. However, if you have not identified that correctly and you put them in a maneuver, you almost could exacerbate their symptoms because the otoconia would not move into the position that you want or migrate into another semicircular canal.

When it comes to calorics, one possible error would be not assessing the middle ear and tympanic membrane status with tympanometry. If the stimulus cannot be in direct contact with the tympanic membrane due to excess wax or debris, your results will not be accurate; they will be diminished. You have to have the appropriate irrigation time, pressure and temperature. Another error I have seen is not allowing the vestibular system to rest in between conditions. Sometimes we are in a hurry or get interrupted and we forget the timing mechanism that is needed in between sides.

At some point while performing vestibular testing, you could have something called chronic subjective dizziness. This is where a patient does not describe symptoms of vertigo, but rather general dizziness or rocking, and where all of your clinical results and other quantitative assessments are within the normal limits. Some of these patients can have other disorders, including anxiety disorders. Sometimes you want something to be abnormal on the testing so that you can help, and when you find that everything is normal, it is disappointing in a way. There are some patients that have subjective dizziness, and although we do not diagnose “subjective dizziness,” it can allow the physician to continue on a different path. Do not be disappointed if your patient is dizzy but your assessments do not support a vestibular pathology.

Perspective from an Extern

When I poll the externs, they have very good responses about errors they now recognize in hindsight. Sometimes I find that externs over-interpret some results, and they do realize that later. They are very anxious to find pathologies that do not exist. We know that experience will assist them with that. One of the interpreting errors we often see with externs has to do with eye blinks. Eye blinks on a recording are often mistaken as nystagmus. They might not be recording long enough to allow for a true response to be seen, or they only take a sample of an inaccurate response or an inappropriate timing of the response. Seasoned audiologists do the same thing.

Another extern error was not focusing on the overall outcome; this is so important because the diagnostic journey is a puzzle. We need to use every piece to make our interpretations and recommendations.

The last extern error is not identifying the primary versus secondary diagnosis. Externs will often discuss a case with me and tell me this whole list of things that they found, but they are unable to focus on what the main thing is. We need to bring that to the forefront. I hope that, as seasoned audiologists, we are describing the main issue to the physician so that treatment can be made in a way that is appropriate. This is one thing that I look for when reviewing medical reports.

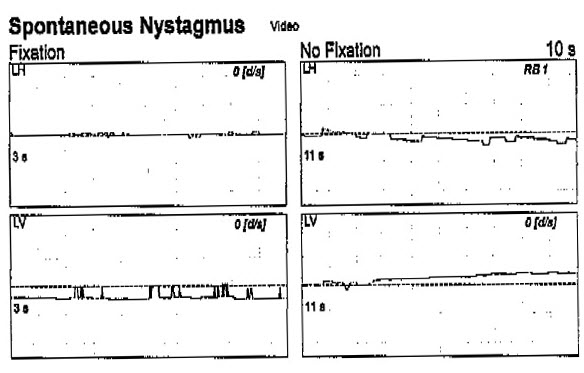

Figure 8 shows an example of over-interpreting a result. This is an extern who had been practicing for one month with us and was seeing a 69-year-old patient. In this particular case, the patient reported that he had three to four episodes of vertigo after a flight to Columbia about one month prior to this test. He also found himself swaying side to side when walking. There were no other symptoms. He does not suddenly move and get dizzy. If we look next to the arrow, you can see spontaneous nystagmus test with no fixation, and the clinician showed me this example, wanting me to see that there was a one-degree right-beating nystagmus. We must use our experience to know that perhaps that is not nystagmus.

Figure 8. Case example of a 69-year-old VNG result, recorded by an extern clinician. The arrow indicates spontaneous nystagmus that was interpreted as right-beating nystagmus.

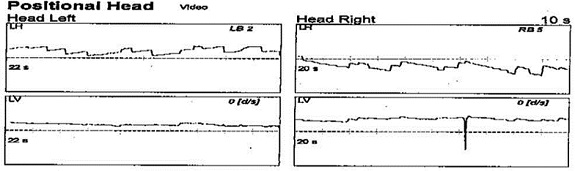

If you look at the same patient in Figure 9, I agree that that is a very good representation of geotropic nystagmus. We see head left, left-beating nystagmus, and head right, right-beating nystagmus. Explaining that every little eye movement is not necessarily nystagmus or a pathology is an important reminder for us.

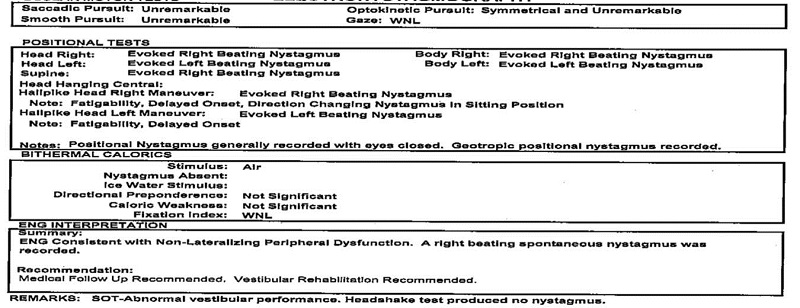

Figure 10 is the medical report that we used for our VNG, and every abnormality was clicked. We want to be effective, we want to be appropriate and we want to focus on the main issues. I did discuss some ways that we could clean this up with the extern, and I did not believe that the Hallpike head-rights and head-lefts had all of those particular symptoms. After discussing it in depth with the extern, the extern did agree. We ended up changing the report, but we still kept the interpretation at the bottom that it was consistent with non-lateralizing peripheral dysfunction. We took out that there was a right-beating nystagmus, because there was none.

Figure 9. Positional data from head-left and head-right conditions that yielded bilateral nystagmus.

Figure 10. Report for 69-year-old male, prior to changes made by the supervising audiologist after reviewing the findings.

I asked the same fourth-year extern after several months, “How do you feel now? Looking back, do you have the same sensitivity to interpreting those VNG results as abnormal?” He responded, “I don’t think I am less sensitive, but more prepared. If I see a horizontal or down-beating nystagmus, I always try to make sure that it is not just an artifact or singular event. Many of my patients produce a lot of noise in their recordings with excessive eye movements and blinking that tends to obscure the results. Now I make sure that what I am seeing is valid through the noise. I think I have become a little less sensitive, and I have a greater tendency to disregard small findings if they do not agree with the overall picture.” That is perfect and exactly what doing an externship brings to a clinician. It allows them to elevate to a new level, and improve their validity, credibility and interpretation skills.

Perspective from a New Audiologist

I have another perspective from a second-year audiologist who said, “Often we go through case history and are concerned with the patient's recent complaints. However, certain vestibular dysfunctions can occur years prior and leave a lasting effect on the results. I had an elderly patient with brief dizziness upon standing. Caloric testing indicated a unilateral weakness; all other findings were normal. After the examination, I decided to follow up with another question: ‘Has there ever been a time in your life that the world started spinning for many hours?’ The patient seemed surprised, and said, ‘Yes, but over 40 years ago.’ It plays a factor on interpretation of results. Secondary to the patient's complaints, he had a compensated unilateral weakness at this moment in time.” Without knowing that in the case history, perhaps recommending treatment based on an acute unilateral weakness finding is very different than recommending treatment on a compensated unilateral weakness.

Here is a polling question: When is vestibular compensation most effective? When patients are taking vestibular suppressants, patients continue to move in the position that makes them dizzy, or when patients wear glasses? The correct answer is when patients continue to move in the position that makes them dizzy.

ABR Reminders and Cautions

There are some general reminders when conducting an ABR. For electrode placement, prepare the skin to obtain the best impedance you can. We know that sometimes you do not always get low impedance, but more importantly, you want impedance equivalent between electrodes. Ideally, we want them all low and equivalent, but if we can only have one, then it is more important to be equivalent.

We need to make our test parameters optimal. When working with externs or someone fairly new to these tests, I do strongly recommend that if something looks abnormal, you must always try to make it normal. Change to the slowest rate, the best filters, perform more runs, et cetera. If something is truly abnormal, it is not going to go away because you changed a parameter. Being sure of your results or retesting is always going to prevent a false positive or a false negative.

Control for ambient noise and make the room quiet and calm. Even fluorescent lighting in your room or the adjacent room could obscure the ongoing EEG information. The patient’s state should be quiet and calm. Cell phones should be turned off and removed from the body. Be mindful that pacemakers can interfere with the ongoing EEG as well.

General Errors in ABR

Let’s discuss general error possibilities when doing an ABR. First is failing to assess the middle ear status. Next, the insert earphones are often switched right into left and left into right. We also can have channel switching where the electrodes are not in the correct channels, inconsistent or incorrect wave selection, not masking in the presence of an asymmetrical loss, not addressing the impact of hearing loss above 4000 Hz on the ABR, not addressing the impact of conductive loss, and failure to change the stimulus polarity for clicks in a pediatric test to assess the cochlear microphonic. In other words, you should be doing one rarefaction run and one condensation to see the positive and negative deflections, indicating that there was a stimulus at the cochlea. You should observe a clear latency-intensity function, with a nice wave V that shifts out with the lower intensities.

Perspectives from an Experienced Audiologist

Let me present some perspectives that are very interesting from a 10-year audiologist about ABRs. She states, “One issue I am picking up on is cerumen in pediatric ABRs. Despite the fact that otoscopy yields clear canals and tymps are appropriate, I have had a few babies who, after placing the insert earphone, would have no response at high intensity levels. Upon verifying, I noticed the issue was cerumen. For some reason, slight cerumen, though not noticeable to the eye or maybe considered minimal due to the fact that we can view the tympanic membrane, still can get pushed into those insert earphone tips.” Personally, that has happened to me more than once. I did a self ABR once because I had tinnitus in one ear. I put the insert earphone in and I ran responses. I did not get any. Thinking I had an acoustic neuroma, I went to the physician and he told me to retest myself, and clearly there was cerumen in that tip. That is always a big lesson to learn.

The audiologist continued, “Since then I have made a point of changing the insert tips and rechecking at the high intensity runs to confirm or negate the initial response.” She goes on to say, “I have had incidents of no function in an ear. Upon rechecking that same ear at the same intensity on another channel, the patient will then pass.” This is a good lesson in cross-checking when we suspect a problem. Perhaps there is something wrong with a channel. That troubleshooting technique can help avoid a false positive or false negative. “When a patient has no response on the ABR on one side, it behooves the clinician to check: 1. The tip for cerumen; 2. Inserts for leaks; 3. The channel being used.” Verification cannot be stressed enough in these tests.

In review, especially with pediatrics, we constantly need to verify ourselves and our testing techniques, making sure that the results we obtain can be repeated and are confirmed. For VNG, there are errors that occur if we are not paying attention to our behavior, our patients’ behavior, or we are over-interpreting or even under-interpreting results. When in question, hopefully you have some clinical support and colleagues to call on. There is no shame in asking someone for an opinion on your outcomes and your work for the best interest of the patient. Obviously with ABR, particularly infant ABRs, we want to be assured that all of our results are obtained on the best equipment with the best set-up and that there are no user failures there that we might have missed.

Risk Factor Areas

Cindy Beyer: Let’s recap some of the areas where we find that our risk for audiology error increases (Figure 11). This is going to include the things such as wrong treatment, wrong hearing aid recommendation or therapy provided, and wrong site treatment, such an earphone reversal. We have talked about working with age extremes, which requires additional care and expertise. Inexperienced clinicians and unsupervised externs are more likely to experience a higher degree of clinical error, and that is where they are going to need our support. For those of us that have been in the field, a lack of continuing education and quality learning experiences may leave us with inadequate knowledge and some outdated information; we want to be aware of that. Unfamiliarity with state-of-the-art equipment might be a factor. Lastly, fatigue, distraction and poor record keeping can lead to misdiagnosis or error in a clinical situation.

Figure 11. Summary of risk-for-error areas within audiology practice.

As I mentioned, HearUSA has a systematic process of collecting and reviewing data. In the past 25 years, we have seen over a million patients and dispensed hundreds of thousands of hearing aids. We centralize reporting of incidents, which are unexpected, adverse outcomes to the patient. We also centralize complaints and track them by frequency and type of complaint. This way, we are able to benefit from trending and tracking to share the knowledge with our co-workers.

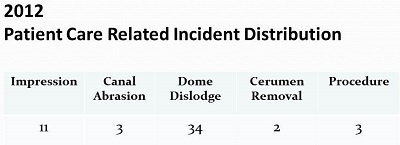

During 2012, you will see the results of our patient care-related incidents (Figure 12). There were 52 such incidents compared with about 200,000 patient visits, which is a very small percentage of the actual number of patients that we see. As I said previously, ear impressions are going to be the most risky. You can see that we had 14 incidents that are related directly to the impression. Thankfully we did not have any serious ear impression incidents last year. When you are taking close to 100,000 ear impressions a year, again, this is far less than 1%. Most of the incidents were abrasions, where there was a scrape or an irritation of the wall by the block or the impression when it was removed. We did not have any serious cases of embedded impressions where we had to go to great lengths to get them removed. We did have two cerumen removal incidents of very minor abrasions to the ear canal.

Figure 12. HearUSA patient care-related incidents for 2012.

The area with the highest frequency of occurrence is with dome dislodgements. We continue to see on a regular basis that we have dislodged domes from hearing aids that are stuck in the ear. Many of them we can remove in the office, but some of these have to be referred to a physician, and we have to get medical intervention in order to safely remove them. I think we can safely say that, in most cases, the manufacturers have migrated to the click domes for better retention, but we still have tens of thousands of earliest-generation hearing aids with the domes. The three remaining incidents were related to some type of a procedure error, and were nothing too serious on the part of the patient or the provider in the past years’ worth of data.

What Happens When Clinical Errors Occur?

Even in the best of practices and despite our best efforts, each of us at some point will experience some type of a negative patient outcome. Hopefully that will be much more of a minor incident than some of the serious ones that we have shared with you here today.

What do we do when an error does occur? It is worth taking a few minutes to talk about this, because it is part of the process of reducing risk and learning from situations that we experience. First of all, we are going to recommend that you fully document the circumstances and the details of the event. That is so important. It is fresh in your memory, so be sure that you write things down. If there is medical intervention or support that is needed at the time that the incident occurs, when the patient is still there, call that physician on the patient’s behalf, explain the situation, and ask if the patient could be seen by that physician or if there is an ENT.

What do we do to immediately try to resolve the issue that the patient is experiencing?

We want to then make sure that we have some follow-up in place. We are going to call the patient back and inquire as to the status of their condition some 24 to 48 hours later. Sometimes it is nice to have a third party do that inquiry for you. Maybe it is a co-worker or a supervisor, but it is important to show that concern and to demonstrate there is compassion and concern, and to utilize what we call the “blameless apology.” Saying “I am sorry this happened to you” is very differently than saying “I’m sorry I did that.” We are suggesting that you demonstrate to the patient that you do have compassion and understanding for their situation.

In many cases that I have personally followed, one comment has been that the provider seemed more concerned about the trouble they would be getting into than what happened to the patient, or the patient expressed to the provider that they were in pain, and they received a very apathetic or clinical response. That can add insult to injury, so be aware of that. Always show compassion and use the blameless apology.

Traditionally, when errors that have been are attributed to mistakes of individuals, those people are very afraid of the penalties that could result from that. Clinician guilt, fear and embarrassment often leads to a position where we deny that there was an error or that we mishandled something, or we tend to dismiss some of the patient’s issues. Hospitals, insurers, and attorneys will frequently advise against using trigger words like error, harm and mistake. Many states have implemented what is called “I’m sorry” laws. The “I’m sorry” laws, which, to varying degrees, render comments that physicians or providers make to patients after an error inadmissible in court. I am not saying that you should fall on a sword and explain to the patient all of the different things that could have come into play after the error, but show empathy and concern, and take responsibility for handling and leading the patient to the correct resolution.

Next, we want to suggest that you do something called a root-cause analysis so that you will clearly understand what has happened and be in a position to minimize the recurrence of that. A root-cause analysis is a class of problem-solving methods that are aimed at identifying the root causes of problems or events. This assumes that we believe that problems are going to be best solved if we attempt to correct of eliminate the root causes and not merely address the immediate situation at hand. That is why we aggregate data. We have people who are experienced with these cases look at them, and we ask a lot of very specific questions. We have a specific form that we use to walk through the situation. We often have a supervisory person that is doing this type of analysis - talking with the provider, making sure that we are getting all of the information. If it is an impression incident, we always take the lot and batch number of the impression material. It may or may not be important, but it is good to have this kind of documentation available to us, not knowing where this particular incident might lead.

A word of advice - you definitely do need to thoroughly document all of the different aspects of the situation, but we are not recommending that you file those details in the patient file. We are recommending that you take those details and a full account of what happened and file them in an incidents file. We always have transfer of records, and we do not want to see any type of bleeding of information from one provider to another that does not necessarily have to go there. Find a place to file those details outside of the patient chart so that it does not get caught up in any transfers and become part of the patient’s medical record.

Again, we want to follow-up with the patient and the physician to make sure that the patient has been remediated to the point that we are able. Keep your supervisor involved all along the way. Take care to have good communication. It is an important part of the recovery process for the patient. If you have a risk management department, you certainly want to let them know. As a word of caution, if you have an incident with a patient that you believe has been managed to a successful place where litigation will not be pursued, but 45 or 60 days down the road you get served with some kind of a lawsuit, be advised that if you have not advised your malpractice insurance carrier within 30 days of that incident, they may not cover you. It is often important just to put the insurance carrier on notice that something happened. Talk with them so that they do not go and try to follow up with the patient before it has even become an escalated issue. If you do not notify your carrier that there was a potential incident within 30 days, they can refuse to pay if it becomes something that involves a medical malpractice suit. Of course, if you have in-house legal support, you want to engage them, depending on the extent of the circumstances for that particular case.

Improving Patient Safety

Improving patient safety is always something that we want to look toward doing. Find out why the error happened. Use your root-cause analysis to help you with that. Strategize with your colleagues about new methodologies. Look at your work flow, tools and processes. What could have been done? Is this the one in a million event, or is this a trend that is happening? Is there anything that could have been done to prevent it? Do your best to foster a culture where people are interested in the quality of care, and they freely discuss near misses, risks, and problems. Having people be fearful of their job or defensive is not conducive to overall elevating the standard of care and reducing risk.

Patient education is an important part of the process as well. Make sure that they understand what is involved, the risks, and how you are going to be a part of their ongoing care. Quality oversight is necessary if you work with other persons, especially if you are in a supervisory capacity. You need to watch what people are doing, and you need to offer assistance, training and redirection where appropriate. Not everyone gets the same level of education. Not everyone has the same degree of expertise or skill or experience. Identifying issues and training staff is very important so that we can improve our standard of care overall.

Just a reminder that routine visits and procedures are not always routine. Take good care and use a good discipline process to ensure that there is minimal risk to the patient and the provider. Be aware of the higher risk situations that we talked about today. It is not possible to do everything right every time. You want to look at the highest risk and probable areas for errors and make changes or enhancements to your current procedure so that you will have a better result.

To the extent that you do encounter an adverse incident, handle it with concern and professionalism. Manage it to the very best probable end, and then train, re-train, and foster that culture of excellence and sharing so that you and your colleagues can help us to move the practice of audiology forward and promote the best outcomes for our patients.

Questions and Answers

For which routine procedures would you advise getting signed informed consent forms?