Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Preventing Medical Errors in Audiology presented by Cindy Beyer, AuD & Suzanne Younker, AuD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Identify the highest probable origins of adverse audiology outcomes.

- Discuss common audiology errors and steps to minimize them in an audiology practice.

- Explain the benefits of a root cause analysis and risk management program.

Introduction

Cindy Beyer, AuD: During this course, we will be discussing different aspects of audiology and practice errors. Suzanne and I have worked together for the better part of about 30 years now, and during that time, we have worked through a number of experiences that we will be sharing with you. We have developed quality management and customer service program for a large hearing care company. In that regard, we partnered with health plans and entities that expected robust quality and care-oriented environments, and this is what we learned, created, and implemented over a period of time. For many years, we centrally managed thousands of cases across the country with a very diverse caseload with hundreds of different providers. We learned so much and had the opportunity to observe, experience, and manage many different types of circumstances. It is from those decades of working with patients, providers, and different situations that we can share with you the different topics today.

Agenda

- Error and Liability Overview

- Administrative Errors

- Clinical Errors

- Treatment Errors

- Preventive Errors

- Risk Management

- Summary and Closing

We will begin the discussion with an overview of healthcare errors and liability, then we will dive into the very audiology-specific types of errors. We have grouped these into different categories. I will start off with an overview of errors and liability and then go into some administrative and housekeeping errors. These are things that happen in the office environment that ultimately can impact the care and safety of our patients, then Suzanne will talk about clinical treatment and preventive errors. Finally, I will close with a few comments about risk management. Hopefully, by that point, you will see the importance of taking the time to put together some preparations before something goes awry.

Error and Liability Overview

Why an Errors Course?

- Hearing healthcare is not immune to risk

- The cost of providing and receiving healthcare continues to rise

- The complexity of amplification and hearing loss evolving

- The cost involved to resolve cases of medical liability

- Increased regulatory responsibility instilled by licensing authority

- Ethical responsibility to minimize the risk of error in delivering hearing care

Let's begin by considering why audiologists should be concerned with an errors course. We know that some states require the course for the purposes of audiology or hearing aid dispensing licensure, but let's think beyond that. Some of you may have experienced an adverse incident. You know firsthand how upsetting those situations can be. Maybe a patient was injured in your care, or perhaps filed a claim against you. If nothing else, you may have felt the discomfort that comes from a patient or a child in distress from say a bleeding ear. Comparatively speaking, audiology is low-risk for both the frequency and the severity of a clinical error, yet we still have the ethical responsibility of protecting our patients against adverse incidents. Plus, we have the desire to protect ourselves and our practices from a financial penalty. The cost of providing and receiving healthcare continues to rise each year, partly because of the risks and liability associated with the delivery of care.

As healthcare advances, the complexities of diagnosing and treating medical problems also increase. Millions of dollars are spent in resolving cases of medical liability. Regulatory agencies continue to impose more and more responsibility on the licensed provider. Thus, it is in our best interest and in the interest of our patients to take some reasonable precautions. To ensure our livelihoods as licensed health care providers, we need to be aware of some of the areas that might cause a loss of license or disciplinary action.

Medical Errors

- 2016 John Hopkins study reported medical errors as 3rd leading cause of death

- 250-4000 deaths

- More than AIDS, MVA, breast cancer

- 2.4 million prescriptions filled incorrectly

- 7,000 people die from medication errors

- Cost the nation $17- 29B annually

- 74% are preventable

A few years ago when we did this presentation, we reported some pretty serious facts. We talked about medical errors being the third leading cause of death. Between 250,000 and 440,000 lives per year were attributed to medical error. And, 10% of all U.S. deaths were attributed to medical error, and 74% of those errors were considered to be preventable. At that time, medical errors were reportedly killing more people than AIDs, motor vehicle accidents, or breast cancer.

Adverse Effects of Medical Treatment

- Recent studies have revisited that research

- Much lower numbers of death and contributory numbers (<6000)

- Conclusions:

- AEMTs are not uncommon;

- the vast majority of AEMTs that occur in patients who die aren’t the primary cause of death;

- only a relatively small fraction of AEMTs are due to misadventure or medical error; and

- population-adjusted AEMT rates have been slowly decreasing.

Then, we fast forward to 2020 and recent studies who now say that those studies were flawed or misinterpreted. The real number is less than 6,000 deaths per year that are attributed to medical errors. That is a huge difference. The new acronym is AEMT, stands for adverse effects of medical treatment. It is now said that AEMTs have decreased over the past few years, and while they are still not uncommon, the vast majority of people do not die from them. This is really good news for all of us since we are consumers as well as providers. Taken as a whole, the picture is improving in terms of the overall impact of adverse effects of medical treatment. It might be increased attention to the topic that is helping as well as a better understanding of the data.

It Happens!

- Odds are if you practice long enough

- See enough patients

- See a diversity of patients

- You will encounter an adverse and unexpected outcome

The odds are that if we practice long enough and if we see enough patients, and in particular a diverse caseload that includes age extremes, at some point, we may face an unexpected and undesirable patient outcome.

Adverse Events

- Adverse event – caused by medical management rather than the condition of the patient

- Examples: abrasions to the ear canal during impressions or cerumen removal, an embedded impression that couldn’t be removed without pain to the patient, PE tubes that were extracted through an impression, earphones reversed, insufficient masking

Ask yourself, have you ever encountered an adverse event while performing a hearing care procedure? Have you ever come close to something unexpected in the course of your work? An adverse event is defined as something that was caused by medical management. An example could be an abrasion to the ear canal, an embedded impression that was very difficult to get out of the ear or could not get removed without medical intervention, PE tubes that were extracted through an impression, reversed earphones, or a failure to obtain accurate test results. Any of those would be considered an adverse event. If you are fortunate and have not experienced such an event, you may know a colleague that has. Over the course of my career, Suzanne and I have seen many such cases as they unfortunately happen.

Do No Harm

- Standard of Care establishes uniformity across individuals in an organization & sets expectations for acceptable performance.

- Practice in the best interest of the patient

- Protects the provider from potential liability issues

- Follow established clinical guidelines to assist us in delivering conscientious and appropriate care

- Scope of practice and best practices documents are available

- American Academy of Audiology www.audiology.org

- American Speech and Hearing Association www.asha.org

- International Hearing Society www.ihsinfo.org

Do no harm is the first rule in medicine. As health care providers, we subscribe to that premise. One of the best ways to minimize harm or risk to our patients is to follow established clinical guidelines that assist us in delivering conscientious and appropriate care. There are "scope of practice" documents available from the American Academy of Audiology and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, and hearing aid dispensers can also find resources at the International Hearing Society. We encourage you to become familiar with these and to follow best practices. Your organization may wish to detail procedures that are very specific to your practice or your patient base, but it is important that you have a process in place. Everybody in your practice, that is involved in the delivery of care, should be fully aware, well-trained, and hold each other accountable for actions. This cultivates an environment of care and consideration that is extremely important in minimizing clinical errors. Standards of care establish uniformity, and they set expectations for acceptable performance. The result is that the care will become safer for our patients, and liability for the practice will be minimized.

Types of Errors

- Errors of omission occur as a result of actions not taken.

- Not performing the right test when indicated

- Not performing all parts of the test

- Not making hearing aid or a physician referral

- Errors of commission occur as a result of the wrong action taken.

- Incorrect masking or procedure

- Incorrect test interpretation

- Wrong hearing aid recommended

- Poor programming

We can categorize the errors into two main types: errors of either omission or commission. Errors of omission occur as a result of actions not taken. Examples of these might be not performing the right test when indicated, such as neglecting to perform masking, not performing all parts of the test, such as not doing bone conduction, and not making the right hearing aid recommendation or the right physician referral. You also may not document a patient visit. Errors of commission occur as a result of the wrong action taken. Examples of those would be using an incorrect procedure, incorrect masking levels, or an incorrect test interpretation. The wrong hearing aid could be recommended or a poor programming strategy results in an unsatisfactory outcome for the patient.

What is a Liability?

- An adverse incident may result in an injury to the patient

- Injury may encompass a broad spectrum of incidences

- physical injury

- unintentional mismanagement of a patient’s hearing loss

- Liability refers to the responsibility for the damages that occurred as a result of the incident

- Malpractice can be either a deliberate or a negligent act committed by a health care provider

- Circumstances could result in a report to the NPDB

With the privilege of being a health care provider, we also have the responsibility of delivering care in a competent and disciplined manner, consistent with the rules of medicine. We study hard and spend many years earning a degree to obtain a license to practice in our chosen profession. With a license to practice and earn our livelihood also comes responsibility and accountability. This is spelled out in the state licensing regs quite clearly, with both financial and criminal penalties when things go wrong.

Malpractice can be either a deliberate or a negligent act committed by a health care provider, and that it results in injury or another adverse outcome to the patient. The injury could encompass a broad spectrum of things from a physical injury to unintentional mismanagement of a patient's hearing loss.

What you might not be aware of is that an adverse incident could result in long-standing or career-altering circumstances. This could happen via a report about you to the National Practitioner Data Bank, commonly known as the NPDB. The NPDB comes into play during the provider credentialing process.

Provider Credentialing

- Credentialing is the processing of enrolling into an insurance plan or network

- This involves a thorough and detailed investigation of a provider’s credentials (education, experience)

- Looks at provider’s interactions with various entities

- State Licensing Boards

- Office of Inspector General (Medicare, Medicaid)

- National Practitioner Databank

Most of you are familiar with credentialing, which is the process of enrolling in an insurance plan or a network. It is a rigorous and detailed investigation into a provider's background that examines education and experience as well as the provider's interaction with various agencies. These include licensing boards, the OIJ, which regulates Medicare and Medicaid sanctions, and also the NPDB. Credentialing is very exhaustive and detailed, and it looks closely for signs that a provider has behaved in any way that was fraudulent, unethical, or incompetent.

The true credentialing process requires what is called primary source verification of several key points of data that the provider submits. For example, when a license number is provided, the requirement is to go to the primary source, in this case, the State Licensing Board, to verify that the license is valid, and to determine if there are any disciplinary actions, past or present.

The same would be true about educational status and certifications. They must be verified with the source that holds the point of truth, and this process also includes querying the OIJ for Medicaid and Medicare sanctions, as well as the National Practitioner Data Bank.

National Practitioner Databank

- Information clearinghouse created by Congress

- Improve health care quality

- Protect the public

- Reduce healthcare fraud and abuse

- National flagging system

- Collects information on medical malpractice payments and adverse actions

- Discloses information to eligible entities

- Required to report

- Malpractice payers, hospitals, professional societies, health plans, peer review organizations, accreditation organizations, state and federal agencies

- Required to query

- Entities making employment, credentialing, licensure, clinical privileges decisions

You may not be familiar with the National Practitioner Data Bank. It is a routine component of the provider credentialing process. I want to spend a few minutes on this as it is important to understand how this action becomes a permanent part of your professional record. It follows you for an indefinite period of time.

The NPDB is an information clearinghouse created by Congress to improve healthcare quality, protect the public, and reduce healthcare fraud and abuse. It works as a national flagging system, collecting information on medical malpractice payments and adverse actions, and it discloses that information to insurance companies, hospitals, networks, and other entities that utilize a formal credentialing process. Many organizations are required by law to report malpractice payments and adverse incidents to the NPDB, such as insurance companies, Medicare, Medicaid, and hospitals. Those organizations are also required by law, as part of the credentialing process, to query the NPDB to see if there are actions against providers.

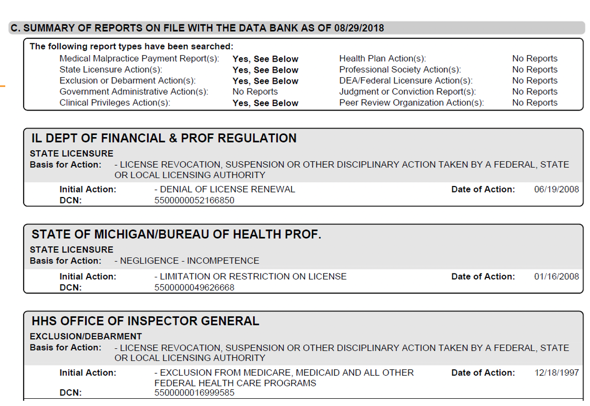

This is a sample of an NPDB report in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Sample of an NPDB report.

This report has flagged medical malpractice. It has also flagged a state licensing report, an exclusion for Medicare and Medicaid, and exclusion/debarment at the bottom. It also has a licensure revocation. With required reporting as well as required querying, this report is going to follow a provider indefinitely with significant implications. This was a bit of a segue, but I thought it was important for you to understand that this creates a risk to a provider. Creating a risk management program in your practice will not only help to safeguard the health of your patients, but it will also help to safeguard the health of your practice.

Categories of Errors

We are now going to look at the types of errors. We have administrative errors, clinical errors, treatment errors, and preventive errors.

- Administrative

- Failure of communication

- Equipment failure

- Record keeping

- Facility Issues

- Clinical

- Error or delay in diagnosis

- Failure to employ indicated tests

- Use of outmoded tests or therapy

- Failure to act on results of monitoring or testing

- Treatment

- Error in the performance of an operation, procedure, or test

- Error in administering the treatment

- Avoidable delay in treatment or in responding to an abnormal test

- Preventive

- Failure to provide prophylactic treatment

- Inadequate monitoring or follow-up of treatment

Administrative Errors

Infection Control

- Provider’s responsibility to ensure patient safety and to provide an environment that controls the transmission of disease from provider to patient; patient to patient; patient to provider

- Elderly patients present with compromised immune systems placing them at particular risk; newborns and infants

- Direct/indirect contact occurs between provider and patient

- Between patient and equipment/tools… in turn come in contact with other patients

- Negligence is probably the biggest fail

- A written infection control plan is required

- Kemp and Bankaitis

- Professional organizations

The first topic is infection control in the administrative section. Now, in the delivery of any healthcare service, it is the provider's responsibility to ensure the safety of the patients served. To that end, audiologists must provide environments that control for the transmission of disease. The spread of infectious disease can happen both by indirect and direct contact. There are several published sources on infection control, including a very well-known book by Kemp and Bankatis, and there are also available course works on AudiologyOnline. If you do not have an active program for controlling infection in your practice, you should really take a close look at that.

Adherence to established infection control protocol is especially important for vulnerable populations and when the potential for contact with bodily fluid exists. The biggest fail in this particular area is one of omission, where providers neglect to provide a program that protects both patients and workers from the active spread of disease.

Pandemic Response Plan.

- National pandemic disaster

- Written process and business continuity plan

- Heightened infection control processes

- Social distancing

- Barriers, scheduling, pathways

- Personal protective equipment - Masks, goggles

- Resources:

In today's pandemic environment, it is imperative that we brush up on our infection control and hygiene processes to ensure that we are following guidance from the CDC and taking the required precautions. There are excellent resources available for providers through our professional associations. I urge you to take advantage of those and have all the proper protections in your office.

Face Mask – Face Shield - Barriers.

- Face masks create communication barriers

- A face shield is an effective substitute

- May allow for visual cues

- Be sensitive to additional hardship

- May need creative accommodations

One thing to keep in mind is that with the barriers that are commonplace today, we need to be sensitive to that. While they are effective in reducing the transmission of germs, whether they be masks or plastic shields, these barriers are disruptive to communication. The masks remove both visual cues and distort auditory information. If you are using the plastic barriers or the face shields, they may still provide some visual cues, but they do distort auditory information. We need to be aware that our patients may need some additional assistance there. They will not have the facial expressions or the visual information on the lips that they typically need to enhance verbal communication. You may need to provide some additional assistance or other accommodations that they might need. This might be a pen and paper or something along those lines to help them through those communication situations.

Common Errors.

- Not washing hands between patients

- Handling unclean hearing aids

- Failure to disinfect patient contact areas

- Infrequent changing of ultrasonic solution

- Failing to clean and disinfect tools - sterilization

- Reusing foam earphone inserts, tympanometry tips, and real-ear measurement (REM) tubing without proper disinfecting

- Not washing hands after handling used tools and equipment

- Improper storage of clean and dirty tympanometry tips

What are the most common infection control errors? The most common one is not washing your hands. We also see the handling of unclean hearing aids. The patient hands us over a dirty hearing aid, and we instinctively stick out our hand and receive it. The hearing aid really should be delivered into a container or a sanitizing wipe to ensure that there is no transmission of bacteria.

Often, there is a failure to disinfect patient contact areas, counters, chairs, and any surface that has been touched by the patient. The ultrasonic solution should be changed after every use. Anything that is touched by a patient needs to be cleaned and disinfected. This includes foam earphone inserts, tympanometry tips, or real-ear measurement tubing. Additionally, the professional needs to wash their hands after handling tools and equipment. Another issue is the improper storage of clean and dirty tympanometry tips.

You might want to consider putting up some posters or signs around the office to remind coworkers of the importance of good infection control. It is something that requires constant diligence. If you see noncompliance, offer a friendly reminder. It is important to help to police the environment and help each other to stay mindful of the importance of good infection control processes.

Medical Records

- Good record keeping helps us stay focused and develop logical plans for patient care; information available when reviewing the file.

- Ask questions: the most appropriate direction of care - hearing aids, testing, cochlear implant, and/or med/surgical intervention.

- Patient files are legal documents and subject to subpoena, audit, and other types of regulatory review.

- Our name and license number are attached to the patient’s record, and judgments and opinions are rendered according to the extent and quality of supporting documentation.

In my experience, and in the many years of quality and clinical oversight, the maintenance of adequate documentation in the clinic is a primary concern. This starts with a good clinical history. It is impossible to develop an effective plan of care for patients without first evaluating their medical and audiological history. By asking the right questions, we are in a position to best determine the right direction of care. This is why we need to explore every question and document those answers into the record.

Good record keeping helps us stay focused and helps us to develop logical plans for patient care. Even though it is time-consuming, there are good reasons for taking that time to record the results of every patient visit. Primarily, it is important to have that information available when reviewing the file and interacting with the patient. However, remember that patient files are legal documents, and they are subject to subpoena, audit, and regulatory review.

Our professional names and license numbers are attached to the patient record, and judgments and opinions are rendered according to the extent and quality of medical record documentation. People will form opinions about our work depending upon what they see written into the record. And of course, remember the old saying, if it is not documented, it did not happen.

Details.

- Keep records of exact hearing aid make, model, circuitry, features, and experiences

- Appropriate recommendations for improvement should incorporate experience as well as current and future expectations.

- If medical clearance is so indicated by the results, make a reasonable effort to obtain it.

- Ultimately, patients have both the right and the responsibility to make decisions about their health care.

- Dates of service, rendering provider in the treatment records should line up with claims documents.

Details are important. Recommendations for improvement should incorporate past experience as well as current and future expectations because we gain insight from knowing what happened when we develop our go-forward plans. If medical clearance was indicated by the test results, it is important to make a reasonable effort to obtain it. Even though the patient may sign the medical waiver, we should take steps to bring a medical opinion into the case when it is indicated, keeping in mind that patients do have the final say in their care decisions. Make sure your dates and notes all lineup, especially if you are billing third parties.

AMA Guidelines For Records.

- Reason for the encounter;

- Relevant history;

- Physical examination findings;

- Prior diagnostic test results;

- Assessment, clinical impression, or diagnosis;

- The rationale for ordering medically necessary tests or services;

- Patient's progress, response to changes in the treatment, and revision in diagnosis as necessary;

- Care Plan; and Date and legible identity of the provider (signature, initials, electronic signature), authentication.

What do we need to put into our documentation? Here are the AMA Guidelines for medical records. Each visit should include the 1)reason for the encounter, 2)relevant history, 3)physical examination findings, 4)prior test results, 5)assessment and clinical impressions, 6)the rationale for recommending any necessary tests or services, 7)the patient's progress, response to changes in anything that you have recommended, and lastly, 7)the care plan, date, and the legible identity of the provider.

AMA Common Deficiencies.

- Illegible notes;

- Incomplete notes, encounter forms, flow sheets;

- Missing or illegible signature;

- Alterations or changes made to the original medical record;

- Use of non-standard medical abbreviations;

- Biased or non-professional remarks;

- Disorganized or misfiled patient records;

- Repetitive, non-individualized notes - especially with electronic medical records; and

- Misuse of rubber-stamped or electronic signatures.

What are some of the common deficiencies in record-keeping? According to the AMA, these are the common deficiencies.

Documentation Errors.

- Failure to document all patient visits

- Failure to initial/sign and date all patient visits

- Failure to include subjective and objective data at each visit

- Failure to document actions and follow up, unresolved problems

- Insufficient amplification history and documentation of needs and expectations

- Missing physician scripts

Over the years, as I have reviewed medical records, these are some of the things that I have come across personally. One is a failure to document all of the patient visits. Another is not signing and dating all of the patient visits. Many notes I have reviewed do not include both the subjective and objective data at each visit. It is also important to document what was done at the visit and the next followup. We also need to document what the previous hearing aid experiences were as well as the patient's expectations. Often, there are missing physician scripts. Of course, this can be a very serious issue if you ever have a Medicare or a Medicaid audit. Missing scripts can be difficult to deal with so you want to make sure that you have that on hand.

Documentation or Billing Error.

- After they self-disclosed conduct to OIG, Towson University Speech-Language & Hearing Center (Towson), Maryland, agreed to pay $10,000 for allegedly violating the Civil Monetary Penalties Law. OIG alleged that Towson submitted claims for audiology services with a National Provider Identification (NPI) number that did not correctly identify the provider that rendered those audiology services. OIG further alleged that for these services to be paid by Medicare, the audiologist must have been credentialed by Medicare as a provider and that audiologist's NPI number must accompany the claim.

https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/psds.asp

This is an example of a documentation error. It may or may not be as we do not have all of the information here, but it became a billing problem. This was a case that was reported by Towson University. They self-disclosed an error. It could have been a documentation error, or it could have been some other type of discrepancy. It was not clear in the article we found. In this case, the provider billing NPI was not the same as the rendering NPI. Thus, there was an OIG violation that resulted in a fine. This did not appear to carry any sanctions or criminal charges, which is good. Towson did self-disclose it, meaning that they caught the error and reported it to avoid any risk of perceived impropriety. We do not know how many claims it involved, but it goes to show that there can be repercussions to something that could have been as simple as a documentation error. If it resulted in a sanction, it could have had a far-reaching impact. But in this case, it seemingly did not.

Unlicensed Testers.

- Audiology Practice with Locations Throughout Central New York to Pay More Than $566,000 to Settle False Claims Act Claims (Dec 2018)

- United States Attorney Jaquith said: “… provided improper inducements to attract patients, allowed audiology testing by unlicensed and unsupervised employees, and then falsely billed Medicare and TRICARE as if the exams had been done by professionally licensed audiologists.

- The inducements included entering beneficiaries into a contest for a free iPad, and offering beneficiaries free Butterball turkeys, $15 Visa gift cards, $15 Dunkin Donuts gift cards, and $30 Omaha Steaks gift cards

https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndny/pr/audiology-practice-locations-throughout-central-new-york-pay-more-566000-settle-false

This was another case that we found reported. This one was seemingly much more serious. This was a practice in New York that was fined over a half a million dollars due to discrepancies in their documentation, but it seemed to go a lot farther than that. There were also some inducements there. I included it as an administrative error because it has to do with the office environment. However, this seems like it was a little more egregious as it took place over a seven-year period.

There was testing that was done by unlicensed personnel that was billed under an audiologist's name and provider number. It came across as a violation of a false claim statute. Again, we do not have all the details here, but the fact that the fines were so much steeper. It was a $566,000 fine, and this one did incur other allegations. There were also some issues related to false claims and kickbacks which makes it appear to be an act of commission as opposed to omission.

I hope these examples illustrate how documentation and administrative issues can really get the practice on the wrong side of an administrative error.

Identity

- 15 million patient records compromised in 2018 – up 270% from the previous year

- Stolen health information is a valuable commodity

- Take steps to ensure that patient identity is established and verified

- Fraud

- Record mix-ups

- Identity theft

- HIPAA issues

- Take steps to ensure that patient identity is established and verified

https://www.experian.com/blogs/healthcare/2019/07/safeguard-patient-data-prevent-medical-identity-theft/

An identity error is when someone steals another person's identity. This can certainly compromise an individual's ongoing care and treatment. Additionally, this type of incident can result in medical records being intertwined, and the subsequent efforts to detangle them can be very challenging. I have seen this happen, and it creates confusion. It also impacts the quality and safety of care, and it is not easily remedied.

As a side comment, protected health information is valuable on the black market because it can be used to obtain pharmaceuticals, commit insurance fraud, and obtain medical care through covered services such as Medicare and Medicaid. In fact, according to the FBI, stolen health information can get up to $100 on the black market compared to a social security number which goes for less than $1 now.

Medical identity theft costs the health industry of more than $30 billion a year, and patients have to pay a lot of money to try to resolve them. The message here is to take adequate steps to verify patient identity in your practice using a valid photo ID and be aware that someone might try to utilize another person's insurance to get a financial advantage. This also creates a safety issue.

Housekeeping

- Safe environment

- Wires

- Chairs

- Steps

- Booth

- Facility issues

- Slip and fall

- Bumps, bruises, breaks

The next issue that we have is housekeeping. I mention this because a safe environment is going to be important in your practice. You want to make sure that your pathways are free of tripping hazards and your chairs are sturdy with arm supports. Keep a keen eye out to observe anything that could potentially lead to a slip and fall. Steps should be well-marked and have handrails. Escort patients into the booth and make sure that they are alert to a step up if that is applicable. In one instance, we had a patient who entered the booth very enthusiastically sat in the chair, knocked some accessories off the wall, and got hit in the head. She filed a lawsuit against the hospital and the provider. Personally, I had a patient that was stepping into the booth and holding onto the doorframe for support. The heavy (self-closing) door closed on her hand and fractured it. These are things that need to be addressed around the office before they become hazards to the patients.

This concludes the administrative part. Clinical errors are up next with Suzanne.

Clinical Errors

Suzanne: Thank you, Cindy. Hello everybody. You just heard a nice foundation of administrative errors. Now, I am going to talk about clinical errors and give you some specific examples.

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Benjamin Franklin

- Cerumen Removal

- Evaluation and Testing

- Earmold Impressions

- Hearing Aid Selection and Programming Errors

- Verification Errors

- Continuous Care Errors

I am going to go over clinical errors with a focus on cerumen removal, evaluation testing, earmold impressions, hearing aids verification, and so forth. This will allow you to reflect on the processes that you do daily. It is important to be mindful during patient care as many times during routine procedures we can get distracted and still complete them. This is not good.

Cerumen Removal

- Possibility of clinical error with subsequent malpractice litigation.

- Over 200,000 ears are cleaned of cerumen each week in the United States

- Cerumen management has become a prerequisite to comprehensive patient care within hearing care practices unless prohibited by a state’s licensing laws.

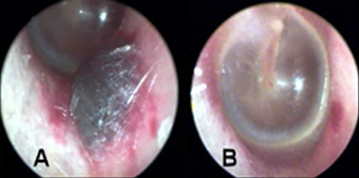

Cerumen removal, in Figure 2, is one of the most invasive procedures that we do as audiologists.

Figure 2. Cerumen in an ear canal.

You have to either go deep into a canal or you have to use certain tools that could cause harm when they are introduced into an ear canal. We work in small spaces and lighting has to be good. Again, we do not want this procedure to be routine. There is a possibility of clinical error with subsequent malpractice litigation. We want to be conscientious.

Over 200,000 ears are cleaned each week in the United States, whether it is done by an audiologist or a physician. It is a prerequisite to provide the services that we do. This is a stopping point for about 75% of the services that we provide. Cerumen can be intrusive to good quality hearing so it is necessary that we perform this procedure. It is state-dependent on whether you can remove cerumen. Our national organizations support it. However, there are no CPT codes for that. You are not necessarily going to be billing Medicare, and your states may have some stricter guidelines about whether not you can do this procedure. You also want to make sure that you are mindful of your own personal limitations. I notice that after 30 years in audiology, my eyesight is going, and I need to wear corrective lenses. We have to have good visibility when we are doing these procedures. We also need to have good stability and dexterity in our hands. Some of us may have arthritis. We need to take all of this into consideration and recognize any limitation that we might have.

Cerumen Removal Contradictions.

- Effusion in the ear canal or other active ear disease

- Hematoma in the ear canal

- Surgical modification of the canal wall

- Unidentifiable foreign objects

- Diabetic patient

- Pending legal proceedings

- Suppressed immune systems

- Bleeding disorders

- A required constraint for removal

Figure 3. A tool to remove cerumen.

There are some contraindications for cerumen removal in your office. These might not be limitations from a physician's perspective, but we tout these in the audiology community. It there is effusion or some active disease in the ear canal, we do not want to complete any procedures in that ear. A hematoma can occur if someone is using a Q-tip too aggressively to get the wax out. I would not proceed with putting sharper instruments into that ear in these cases. Today, we do not see as many fenestrations, but I am sure they exist. Somebody may have had some facial plastic surgery that caused their ear canals to narrow thus they may not be candidates for this procedure. There may be an unidentifiable foreign object. On occasion, we have been able to remove these, but again, we have to be mindful when going into the ear canal.

Diabetic patients are another concern. In fact, it is a good idea to have a consent form that lists pathologies that the patient may have. If they check yes to any of these criteria like diabetes, a bleeding disorder, immune system disorder, et cetera, you may want to take pause and not proceed. You could say, "Unfortunately, I can't do this in this office right now," and refer them to a physician that might have more access to emergency medical procedures should something negative happen.

Cerumen Removal-Common Errors.

- Ignoring contraindications

- Unsigned cerumen consent form

- Neglecting to clean and disinfect cerumen tools

- Canal abrasions

- Improper storage of tools

A common error is when a clinician ignores a contraindication or does not have a consent signed by a patient. Cindy talked about documentation, and why this is so critical. Having a separate document saying that the patient is consenting can bode well on your side. It is also important to be careful to not abrade the canal. Another common error is not cleaning the tools well. You have to use a solution, and it has to be more than just an alcohol wipe. Lastly, when you do have clean tools, make sure they are stored properly. They should be in a drawer, and the dirty ones should be stored elsewhere to keep infection control in line. Figure 4 shows a very sizable subdermal hematoma in the right ear (AD) 24 hours after an incident.

Figure 4. Sizeable AD subdermal hematoma 24 hours and one month after cerumen removal.

It did heal nicely as shown in picture B. A month later, there was only some slight redness and abrasion at the bottom. This was painful for the patient, and it took a month for it to heal. Figure 5 shows another post-cerumenectomy with a small hematoma.

Figure 5. A post-cerumenectomy with a small hematoma and contusion with bleeding (multiple exostoses).

You can see the abrasion and multiple exostoses in this image.

Common Errors in Audiometry/Testing

- Incomplete or poor case history

- Improper supervision of trainees

- Choosing the wrong test or omitting a test due to time constraints

- Over or under masking

- Misinterpretation/under interpreting results

- Not making a referral when it is appropriate to do so

- When testing children or difficult to test patients, not keeping them on task and getting invalid results

For audiometry, it is so important to keep a good case history. We can be in a rush and not write everything down. How many times do we forget or merge the patient's data? It is critical that you writing things down as you are evaluating the client and documenting that information appropriately. You may also have trainees or audiology assistants working with you. They need to be supervised and trained.

Other examples of clinical errors are completing the wrong test or omitting a test due to time constraints. Here are two examples from my practice. I have seen audiologists that are big proponents of otoacoustic emissions (OAE) testing. If somebody has a flat tymp with fluid behind the eardrum, completing an OAE after that is not the right decision. You have to have a clear middle ear system in order to complete that test. For an omitting example, I have seen audiologists that do not always complete speech recognition thresholds (SRT). They will say, "Oh, it's a waste of time. It doesn't really tell me anything." Then, instead, they do an MCL (most comfortable level), discrimination test, and word recognition test. This is not the best practice. The more we document and do tests appropriately, then should an unfavorable outcome happen, we have all of the necessary tools already completed. If there is a skipping of something, this can come back to bite you.

Certainly, over or under masking are always a concern. There are also misinterpreting or under-interpreting and not making appropriate referrals out to physicians or other entities.

Testing children may be difficult if you cannot them on task. This can be another huge hurdle. When we do these routine tests, we are asking patients to do something. If we attempt to multitask at the same time, we might miss something if the patient is confused, dazed, or daydreaming.

- Improper placement of headphones (reversal) or bone oscillator.

- False-positive air-bone gaps related to insert receiver positioning

- Speech recognition testing at levels too low to reach maximum performance

- Failure to perform annual calibration on test equipment

- Failure to perform daily/weekly listening checks

Another error is improper placement of headphones (reversal) or the bone oscillator. I was working for an otoneurologist who was very much into the surgical side of things. A very famous DJ came in to have his hearing tested. One ear was a flat 50, the other ear was somewhat normal. I thought that the MD was probably going to do surgery. It looked like it was conductive and probably otosclerosis. I got so wrapped up in thinking that I knew what was this was, I ran to the doctor with the outcome. The doctor said, "Nope, this can't be right. Go back and retest." I went back, retested, and got the same 50 dB flat all-conductive outcome on one ear. The third time the doctor sent me back, I realized that my cord was not plugged in all the way to the transducer of the headphone. I plugged it in the all the way and viola, both ears were back to normal. It is important that we pay attention to those things and have checks and balances. Again, during speech recognition testing, maybe people are not taking the time to do an MCL. They will just throw in a 60 dB that is not loud enough to reach their maximum performance. These are small things, but they are considered clinical errors.

We also need to complete annual calibrations on test equipment. In addition, daily and weekly listening checks are good to do as well. However, we get busy and forget. If I had done that before my ENT patient, I would have noticed a cord halfway out of my booth jack. I would then have not embarrassed myself with the otoneurologist.

Audiogram Errors.

- Patient confusion over testing procedures = false-positive or false-negative results.

- Double-check results and make sure that everything “adds up” and those obvious discrepancies are corrected.

We do see audiogram errors, particularly when patients are confused over the testing procedures. We get a lot of false positives or false negatives. Perhaps you have had workman's compensation cases where you have to be diligent about the outcomes that you are taking. You need to double-check results and make sure that everything adds up. I am a firm believer in doing SRTs because it will show me if it matches my pure tone average (PTA) or if it makes sense with the overall picture.

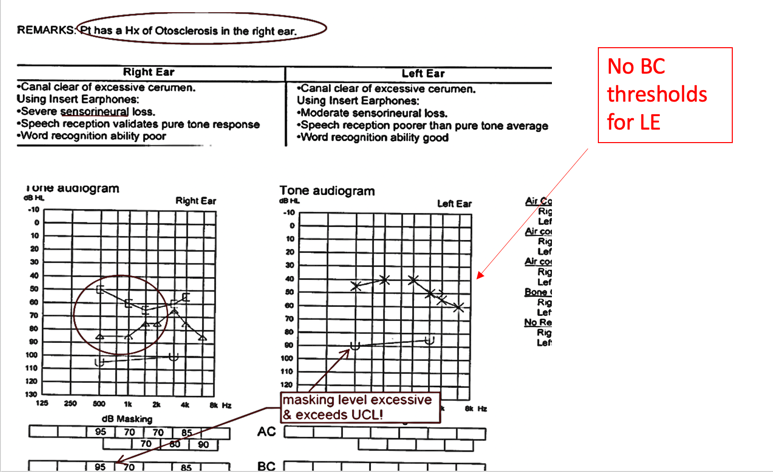

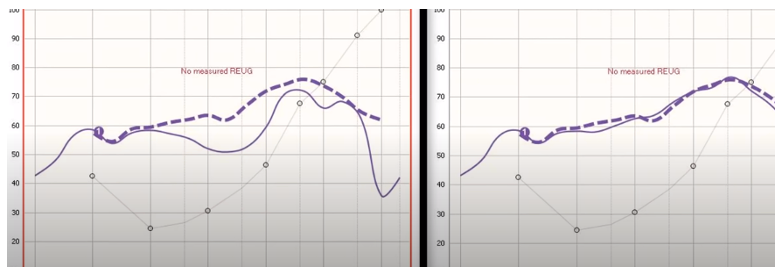

Testing and Interpreting Errors. Here is an example of an error in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Testing/interpreting error #1.

This patient had a history of otosclerosis in the right ear that was well-documented. You can clearly see that makes sense with this audiogram. There is also masked right ear and bone conduction showing. I also see a history of middle ear pathology. However, they interpreted this test result as severe sensory neural. This is an incorrect outcome via an interpretation error. As these are computer-generated medical reports, maybe they hit the wrong key. Again, we are in a quick environment. Typically, there are office management systems with PC-based audiograms. We need to be very mindful and double-check our work. There is also evidence of some masking levels in this case where it exceeded the other ear's UCL (uncomfortable level). This might have caused the patient some discomfort so they were not able to concentrate on the results. There is also no bone conduction (BC) thresholds (no un-masked or even-masked) to understand this. We need to know how much masking and where the other ear stood. Double-checking things makes sense so that we do not run into these errors that look pretty obvious in hindsight. At the moment, they may not be.

Here is another example in Figure 7. This is another one where there is an interpretation error.

Figure 7. Testing/interpreting error #2.

One thing with audiology is that we do not have a standard, per se. Specifically, this air-bone gap needs to be called conductive, mixed, or whatnot. However, there may be some state rules that define significant air-bone gaps, but how we interpret those is what matters. In this particular case, the left audiogram shows two 10 dB air-bone gaps (circled in red). Even though there is no right or wrong, I would say that most audiologists would consider that more of a sensory neural issue. I think we get more concerned when there is a 15 dB air-bone gap, but again, on the medical report (on the bottom), they called this a high-frequency mixed loss. These are slight inconsistencies that do not make sense but can cause a clinician to mistreat, misinterpret, under-interpret, or maybe not fit them correctly with hearing aids. It does have this cascading effect if our results are not accurate.

Recommendation Error. Figure 8 is another example of where somebody was not doing a diligent job. In this particular case, they recommended a hearing aid for the left ear.

Figure 8. Recommendation error.

When we look at this carefully, we are looking at the right ear. And, down below, this person's speech is very concerning. The left ear is better ear having some results of 96% on speech outcomes and great range UCLs. When you look at the other ear, this is not a terrible loss. Now granted, we do not have masking, but there is no reason to see no speech discrimination, and in fact, they are getting no response. This should have been a medical referral for sure, but instead, there was a hearing aid recommended for the left ear. I get that because they are not dealing with the problem ear, but they are also not looking at the overall picture. If this person had something like an acoustic neuroma that was not diagnosed, this would be a very significant interpretation and clinical medical error. Again, we need to be mindful, double-check our work, make sure that we are following all the guidelines of our state, and follow best practices.

Hearing Aid Assessment.

- Hearing aid dispensing is regulated through state licensing or registration

- Testing must include as a minimum, (except where concomitant handicaps or mental or chronological age preclude) speech audiometrics -including word recognition measures, air-conduction threshold assessment, and a measure of middle ear involvement.

If you have done hearing aid assessments for a long time, you can get into a routine. Technology is changing all the time with new hearing aids, software, and features coming out practically every six months for most manufacturers. Staying on top of this information can be a bit confusing, but it is imperative that we do so.

There is required testing, and we have to test certain minimums. The only time we would not test those minimums is if somebody was either physically or mentally challenged and could not give you that information. However, there are other ways to do things. You can be creative with testing to get the most accurate results. Certainly, we need the minimum of speech, and every state law dictates exactly what your minimums are. On the dispensing side of things, the hearing aid fitting language usually is a little bit more precise on what the state expects from you. It requires speech audiometrics and speech testing. They may have more specifics so you need to be aware of your state's minimum requirements. Some refer to the FDA guidelines. They will often list specifics about two or more bone gaps and want you to test air and bone at least at five, one, two, and four. Reading that verbiage will tell you exactly what the state expects of you. They will also want some type of measure of middle ear involvement ascertaining bone conduction. Obviously, we have other enhancement tools to do that as well.

Masking.

- Inaccurate tests due to improper masking can lead to inappropriate recommendations, improper referrals, and inadequate hearing aid fittings.

- Dispensers by law must refer patients with potential medical problems for audiologic assessment when indicated.

Masking is always a challenge. Even seasoned audiologists sometimes can get stumped, and obviously, I am a firm believer in insert earphones as they reduce these dilemmas. It just makes it a lot easier. You have a larger interaural attenuation when you use insert earphones so you do not have to mask as frequently, but it does happen. Inaccurate tests due to improper masking can lead to inappropriate recommendations, outcomes, and inappropriate hearing aid fittings. Dispensers by law must refer patients with potential medical problems for an audiologic assessment when indicated. If they do find significant air-bone gaps, they are automatically instructed to refer out, as we probably would as well. However, we might take the time to do a little bit more investigating, finding the site of lesion for significant air-bone discrepancies.

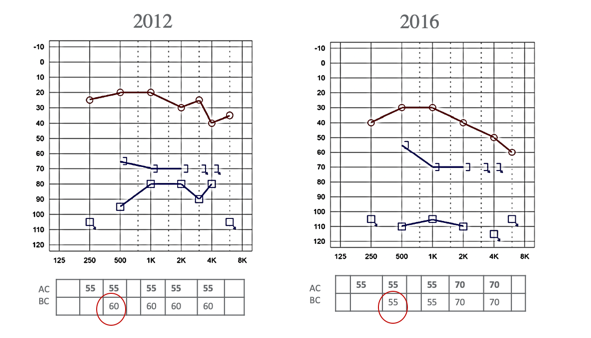

Figure 9 is a case of under masking.

Figure 9. Example of under masking @ 30dB-EM.

This is an interesting case because it is talking about a 5 dB discrepancy. What I want to show you is at the bottom. On the left is a 2012 audiogram. This has some significant findings in the severe to profound range, and maybe some mixed components there. They used 60 dB of masking into the right ear in 2012, and the masking threshold is about 65 dB for the right ear for bone conduction. Four years later, obviously somebody looked back at the old one and was maybe not paying attention. We do run into this. For example, if you are doing an annual check or have an older audiogram, you may tend to be biased when looking at that older audiogram. You may tend to predict or want to predict what your current audiogram will look like. Thus, you may not be as diligent in pursuing things such as masking. In this case, they used a lesser loudness level at 55 dB of masking. Think about this. This was for the left ear. The 55 Db unmasking in the right ear was not quite enough because the threshold got better, and it went up to 55. We know that is not anatomically possible so it must have been due to not enough masking. Again, we want to be as accurate as possible so just being 5 dB off from your masking level from 2012, four years later in 2016, made it look better. This could also be a programming issue. When you put information into the software, perhaps that is not going to give enough gain and output because it did not show that it really needed it (as much as maybe the threshold down below).

Medical Referral

- Coordination of care with the patient’s physician ensures appropriate treatment.

- Refer to established practice guidelines to avoid over or under referring of medical care.

- Under referring, patients may deny patients the opportunity for the most effective and appropriate resolution to the hearing condition.

- Over referral of patients for medical care is costly and inconvenient.

A medical referral is very important. However, we have to take a step back and reflect on what is in the patient's best interest. Over-referring causes physicians to not trust your judgment, and obviously, under-referring causes everybody to not trust your judgment. It is a double-edged sword. Again, be mindful. I am certain over-referring has a cost to it because now that patient has to go to a physician when perhaps it was a minor issue. We made documentation notes about it, but it was not going to impact the overall outcome of the patient. We have to weigh those things and maybe recheck in six months. Those are very responsible things to do.

Earmold Impressions

- An invasive procedure that can lead to complications, and quite probably the riskiest procedure that we perform

- In our experience, the vast majority of adverse events are related to the taking of ear impressions.

- Requires a conscientious approach to inspecting the ear canal and confirming otoblock placement to avoid errors

We do not do as many earmold impressions as we used to do, even five years ago. This is because the majority of hearing aids today are RICs, or receiver in the canal style hearing aids. There is less of a demand for custom. However, a client may still need a custom earmold for the RIC if there is a need for more power or there is an anomaly to the shape of the ear canal. Impressions still may be needed. This is very routine, and we get used to doing it. I have had many students and licensees work on me. To be honest, it was the seasoned audiologists I was most afraid of. They would take their oto-light and their block and be a little aggressive and rough. Perhaps they were paying attention and perhaps not. In contrast, the students were very slow, methodical, patient, and took their time. They constantly looked into the ear to look at the block placement, and I was appreciative. I think we have to do it in a diligent manner if we want to avoid some of the things I am going to be showing you. In our experiences, the vast majority of adverse events that we have seen were related to taking ear impressions. It is the riskiest procedure that we perform. It requires a very conscientious approach to inspecting the ear and making sure that the otoblock placement is absolutely perfect, not only in the position that it is in but in the diameter. An example is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. An example of an earmold impression.

As audiologists, we do hundreds even thousands over a lifetime.

Complications.

- Potential for damage to the outer, middle, and inner ear structures exist…potential increases when taking deep canal impressions

- Complications include- canal abrasions, trauma/lesions to the tympanic membrane and middle ear ossicles; accidental removal of pressure equalization tube; perilymph fistula with resultant fluctuating, progressive, or long-standing sensorineural hearing loss; or concussive inner ear trauma accompanied by temporary or permanent threshold shifts.

There are cases where we even have to do a deep canal. Some people still want a deep-fitting CIC (completely-in-the-canal), and for this, you have to do a deep impression. Again, that enters into another level of being very conscientious as it can lead to canal abrasions and trauma. You can even cause hematomas that showed you from the cerumen removal. These can certainly happen with impressions. You can even go so far as damaging the tympanic membrane, adhering to the middle ear ossicles, and then maybe even removing equalizing pressure tubes. We have seen that many times in the work that we have done with quality assurance and oversight. Even worse, a perilymph fistula can result if you puncture through. This can cause a perilymph leak. This can cause a fluctuating, progressive hearing loss and dizziness. There is a whole host of negative outcomes that can come with these procedures.

Precautions.

- Appropriate bracing should be employed to avoid potential injury of the canal wall or the tympanic membrane.

- Careful examination of the ear canal pre and post otoblock placement to ensure that the material will not travel past the block.

- Especially important when working with young children, patients who may be frightened by the impression process, or patients with complicating disorders that preclude normal neuromuscular control… may lead to unexpected movement.

To minimize the risk associated with ear impressions, a careful examination is needed. When placing the ear light or otoscope within the ear canal, use a bracing technique to avoid potential injury of the canal wall or the tympanic membrane. This is especially important when working with young children, patients who may be frightened by the impression process, or patients with compromised neuromuscular control, which may lead to unexpected movement. It is also very important to visualize the ear canal pre and post block placement, making sure that there are no gaps between the wall of the canal and the block.

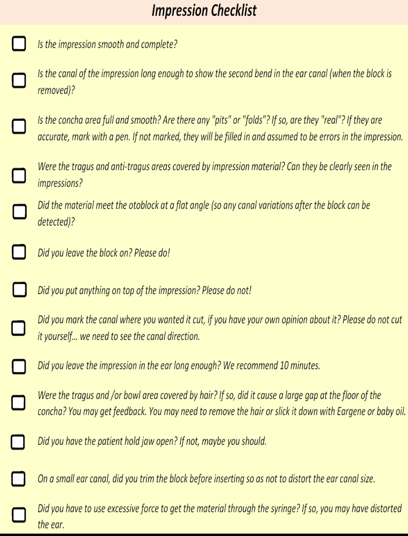

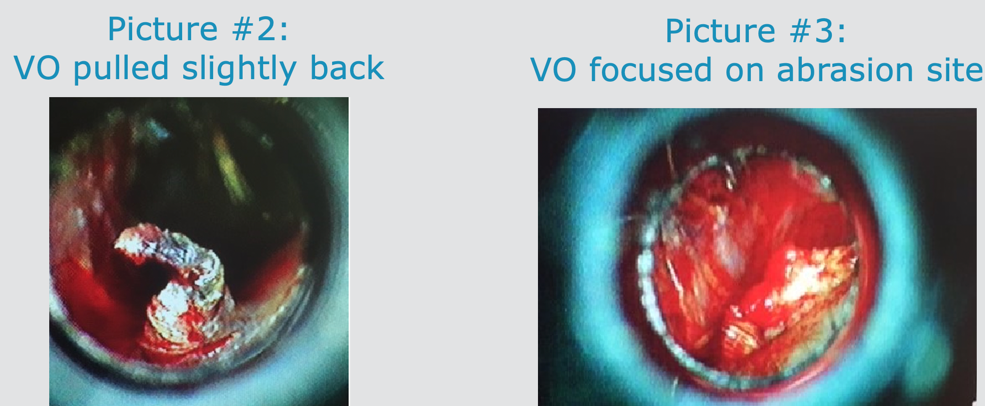

Lastly, we encourage the use and familiarity of an “impression checklist.” This can be posted in the procedure area as a frequent reminder to be diligent. Figure 11 shows an example of an impression checklist.

Figure 11. Example of an impression checklist.

Case 1: Left Ear.

- Impression material scraped from TM under general anesthesia

- Numbness in the tongue, sense of taste distorted

- Subsequent tests and doctor visits indicate further hearing loss and additional health issues (dizziness, headaches, etc.)

- $100,000 claim settlement

Case 1 is where an impression got stuck in the ear and could not be removed in the office. This person had to be referred on the spot and ended up needing a surgical procedure. They either could not get the impression out, or maybe they got some of it out, but there was still some remaining. The patient had to go under general anesthesia so they could scrape the impression material from the tympanic membrane. As a result, the patient had extremely adverse effects including tongue numbness and distortion in taste due to damage to cranial nerves. This client also had decreased hearing, dizziness, and headaches. There was a claim settled for $100,000 due to the severe impact on this person.

If we look at the circled audiogram area in Figure 12, you can see that the patient used to be able to hear in the high-frequency ranges, and now, they no longer could

Figure 12. Case #1's audiogram.

Case #2 Blow By.

- ENT could not remove in the office

- Impression removed under sedation.

- Obliterated the TM, surrounded ossicles, entered Eustachian tube. Pt. demonstrated a significant decrease in AC thresholds- now severe/profound mixed

- Subsequent dizziness and cardiac problems (for which she was hospitalized)

- Pt. underwent surgery to repair TM, one ossicle removed, and replaced- cleaned ET in an unsuccessful attempt to restore hearing.

- Outcome- Settlement of $560,000.

- Audiologist: reported to HIPDB for malpractice history

- Demonstrate a preventive action plan

The second case involves a client with moderate to severe sensory neural hearing loss in the ear that incurred the injury and a severe sensory neural in the other ear. Post-impression, the material could not be removed by either the audiologist or the ENT. This caused severe pain with each attempt. There was a lot of vacuum suction from the impression. While we do have techniques to alleviate that, it is painful if you just tug and pull. This was eventually removed under sedation. The material had obliterated the tympanic membrane, surrounded the ossicles, and then entered into the eustachian tube.

If you are making an impression, and all of your material is used up in that impression incident, that is probably not a good sign. Or if a patient says, "That hurts," that is a good stopping point. The patient may not have said anything or the provider may have said, "It's okay. We are almost done." Either way, the audiologist did not pay attention to how much material was exiting the gun or syringe. Clearly, you want to have an idea of how much impression material you are introducing into the canal. However, in this case, this went on and on with enough material to go down into the eustachian tube.

Figure 13 has a very large blow by. This is not what we want to see, and it is not a good sign.

Figure 13. An example of blow by from Case #2.

In this particular case, the patient had to undergo surgery to repair to the tympanic membrane, and one ossicle had to be removed and replaced. The eustachian tube had to be cleaned out. The patient demonstrated a significant decrease in air conduction thresholds and now presents with severe to a profound mixed loss where before it was a moderate to severe sensory neural loss. This client also complains of both dizziness and decreased hearing. The case was settled for a huge sum of $560,000, and it was reported to the Healthcare Integrity Data Bank. When you have large payouts such as this as a settlement, the malpractice premiums increase. It is not a single cost, but it is a reoccurring cost when these things happen.

Case #3 Dislodged PE Tube.

- 21-month-old child

- “I did not see the gap between the cotton block/canal – allowed the material to blow by the block. The reason I believe the blow by was so serious is because it was a toddler and the canal is so small that there is little margin for error. I have been doing impressions for 25 years. I should have been even more careful… I just didn't see the gap…”

Dislodged PE tubes happened in case #3. This was a 20-month-year-old child with a pressure equalizer (PE) tube. This was a very experienced audiologist who was used to working with pediatrics prior to doing the impression. The actual words from the audiologist were, "I did not see the gap between the cotton block and the canal. It allowed the material to blow by the block."

Figure 14. An example of a dislodged PE tube in Case #3.

"The reason I believe the blow-by was so serious is that it was a toddler and the canal was so small. There was little margin for error. I have been doing impressions for 25 years. I should have been more careful. I just didn't see the gap." We need to be careful each and every time.

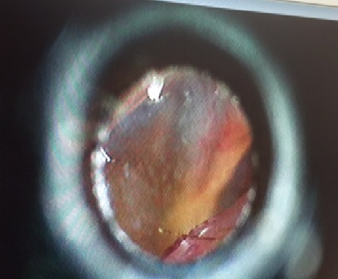

Case #4: VO Deeply Inserted in Canal.

- Day of Appointment

- While inserting the impression material, the patient moved.

- Upon removal, the patient expressed significant pain

- After removal, an inspection of the impression revealed a slight “blow by”.

- Otoscopic inspection revealed an abrasion on the floor of the canal with no blood.

- Tympanometry was normal

- Did not appear to require medical attention

Here is another one. This is not so much a block or an impression being stuck, but during the impression procedure, the patient complained that it hurt when the impression material was inserted. We surmise that the patient moved and the oto-light scraped the bottom of the canal. Upon removal, the patient expressed significant pain, but it was able to be removed. It did have a slight blow-by. Otoscopic inspection revealed an abrasion on the floor of the ear canal, but no blood.

Figure 15. An example of an abrasion Case #4.

When viewing the canal with an otoscope, you could see a scrape or abrasion. When they did tympanometry, it was a Type A so everything was normal. The abrasion did not appear to be that significant, and this does happen with impressions. While we know that there can few scrapes with what we do, the patient was expressing significant pain. This patient came back after a couple of days saying that it still hurt. They put the video otoscope back in the ear and pulled it back slightly so it was not as deep. Now, they could see the piece of skin that was curled up in Picture 2 in Figure 16. Now, you can understand the pain the client was feeling. Picture 3 is another view of focusing on the actual abrased site.

Figure 16. These are other views of the abrasion in Case #4.

Picture #2: The otoscope was further out of the ear. The provider indicated it appeared to be skin that had been peeled back from the canal wall.

Picture #3: The third photo was taken with the otoscope pointed at the abrasion site.

The first pass-around with the video otoscope gave confidence to the audiologist that this was not a significant event. However, based on the patient's claims of it still hurting indicated a second look. This time they were able to see the real issue that had to be treated immediately.

Bridge and Brace.

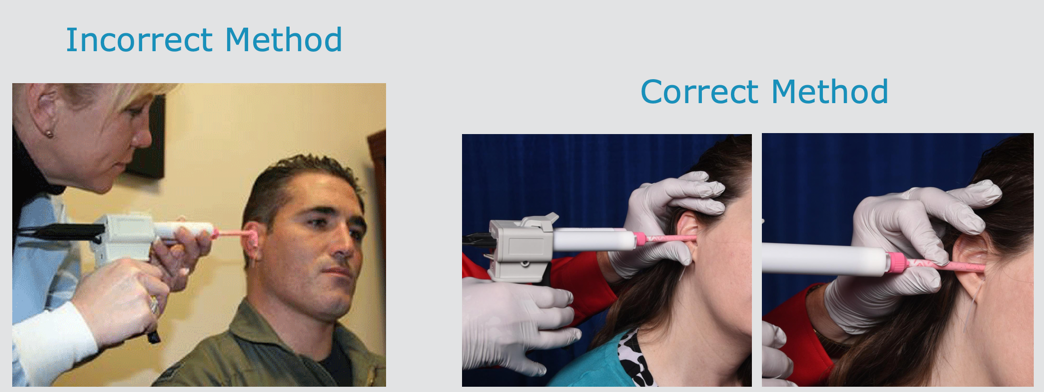

We need to have our techniques down pat and make sure that we are always doing it even when distracted. The bridge and brace technique is demonstrated in Figure 17.

Figure 17. The bridge and brace technique.

Additional Notes.

- Block materials include the traditional cotton and the newer polyfoam. Because of its compressibility, the latter ear dam material is often a poor choice for use with viscous, high-density silicone impression materials.

- Material mix consistency and injection force are also critical variables in the impression-taking process.

- Friable and monomerically scarred tympanic membranes and surgically altered ears are at particular risk.

- The use of a lubricant such as mineral oil will prevent material from adhering to the canal wall

Block materials include traditional cotton and polyfoam dams. People usually have a preference. One rule of thumb is that foam, because of its compressibility, tends to have more bypasses. if you are using a viscous material, it is very "soupy", and the dam may not be the right choice. Perhaps, cotton would be better in these cases. And if your material is very dense that necessitates the squeezing of the gun with a little more force, that could be a problem. This could push that block further in or dislodge the block at a different angle. Friable and monomerically scarred tympanic membranes present other risks. If a block touches that weakened area, it may cause a perforation when pulling it back out. It is recommended to use a lubricant such as mineral oil to keep things very slick and moist to prevent abrasions to the ear canal.

Treatment Errors

Selection and Programming Errors

- With new technology features, come added complexity of multiple programs and continuously evolving options and algorithms.

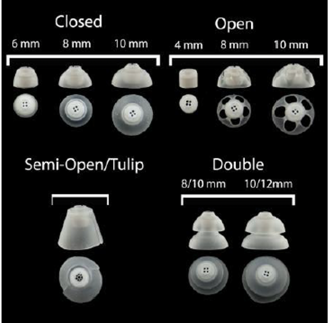

- Remember the basics; the appropriateness of amplification at any given frequency depends on the ear canal length & size, and the amount of ear canal “insertion loss” or occlusion from the dome, earmold, or shell.

- Selecting appropriate dome shape and size matters to the overall success of hearing acuity.

We have fabulous new features that enhance the patient's ability to hear clearly with current hearing aids, multiple programs, and evolving options. Remember the basics and the appropriateness of amplification at any given frequency depends on the ear canal length. Getting back to science, we know that appropriate amplification does depend on an individual's canal length and size. Diameter and length also alter how amplification works in a sound chamber. You will affect the amount of ear canal insertion loss or occlusion when you insert a dome, earmold, or shell into an ear. There is science behind this process that we cannot ignore, and we have to be very conscientious of that when we are fitting hearing aids. We tend to feel that the algorithms of our software will take care of all that, and that is not necessarily true. It is imperative that we select the appropriate dome shapes and size, to make sure that we are accommodating their ear canal length and size, occlusion effect, and hearing loss.

Inadequate Gain.

- Due to Complaint of Poor Speech Clarity: Not taking a low-frequency loss into account and under amplifying the low frequencies.

- Due to Complaint of Voice Occlusion: in a barrel or echoing a commonly made adjustment error is to reduce the input in the low frequencies for all the input levels (i.e. soft/average/loud).

- Changing dome-style/venting, but not updating in the software.

- Not considering manufacturer recommendations on receiver strength and dome size; open fit is not always the best fit and is not always the answer to occlusion issues.

There are some common things that happen with the sophisticated programming options that we now have. We may not trust what we are doing or what our computer software wants us to do. There may be a lot of inadequate gains. I have seen this personally in clinics. Everybody wants to decrease the low-frequency gain, and this is not the best choice in most situations. When you have a complaint of poor speech clarity, you may need to increase the low-frequency gain because of that insertion loss. They are not getting the base frequencies to give the speech the quality that it needs. Lowering all the low frequencies is not an appropriate procedure unless you are taking everything into account

A "voice in a barrel," occlusion, and echoing are common complaints. The first thing people do is reduce the input of the low frequencies. However, that is going to affect all of the sounds for soft, average, and loud, and this is not the appropriate direction to go into.

I also see the changing of domes. The patient comes in, wants you to change their hearing aid or their dome. You may replace it with a different dome. This will change the amplification acoustics and will change how that patient is able to successfully hear. But if we intentionally did that because we felt that they needed a different vent or style, it is important to update that in the software as it will take into account all of those specific accessories of the hearing aid and make subtle adjustments based on those things.

You also want to consider receiver strength and dome size. Is it an open fit or closed fit? All of that is important. Every time you make a change to those accessories, you need to put that into the software as it will change the acoustic parameters. Without doing that, you are not giving the patient the best amplification outcomes that they should have.

User Doesn't Notice Much Difference.

- The complaint of not being able to tell a difference between wearing and not wearing hearing instruments other than a noted increase in sharpness of sounds.

- Failure to attain the full potential of the hearing aid over time

This issue comes up a lot. Sometimes users do not notice a difference between wearing a device and not wearing one. I have seen this a lot when a patient is a new user. They get a hearing aid and go through a honeymoon effect where they feel that things are great. When you bring them back, let's say six months check, they say, "I don't notice a difference." They may not be getting that increase in sharpness. The audiologist has failed to give the full potential of the hearing aid over time. Some manufacturers call it acclimatization or they may have a different term for it. Many times we will start the new user on a very lower amplified setting than what the target is. If we do not put them on a naturally automatic increase in gain and output for their soft, medium, and loud inputs and they are not getting that gradual increase up to the target, they are going to come back in six months and say, "I'm not noticing anything. It behooves us to give them that opportunity each and every time, to experience the potential of the hearing aids. Then, they will continue to say that it is beneficial at their six-month check. You are to bring them up to their target levels in small increments.

Feedback Issues.

- If the feedback control system has been run but feedback persists a common adjustment error is to reduce the gain for all inputs in the high-frequency region which may reduce speech intelligibility.

- The adjustment may be to decrease the gain only for the soft input curve in the high-frequency region

Fortunately, today's software and instruments have excellent feedback control systems. Sometimes you do have feedback that persists. A common error is to reduce the gain for all the inputs in the high-frequency region which is where we know feedback occurs. However, we have to consider that that is going to reduce speech intelligibility. They may have needed that high output and gain in the high frequencies because that is where there are losses,. We need to manage the feedback in a different way in these cases. We could change the dome, and it is okay to occlude patients if they need it. They will come to appreciate and get used to it. Maybe, adjustments can be made to decrease the gain only for the soft sounds in the high-frequency region. That could be another strategy. Be mindful and do not address an issue with the same procedure that you do for every patient. This could be doing a detriment to their hearing health, and they may not get the full potential of that hearing aid. Doing all the right things has you winning in the end with that patient.

Hearing Aid Programming Error.

- Patient dissatisfied

- Severe loss bilaterally

- Initially fit with mid-level; exchanged to high-level due to lack of noticeable benefit

- Several check-ups for “Thinks they need to be turned up.”

- No contact 6-months

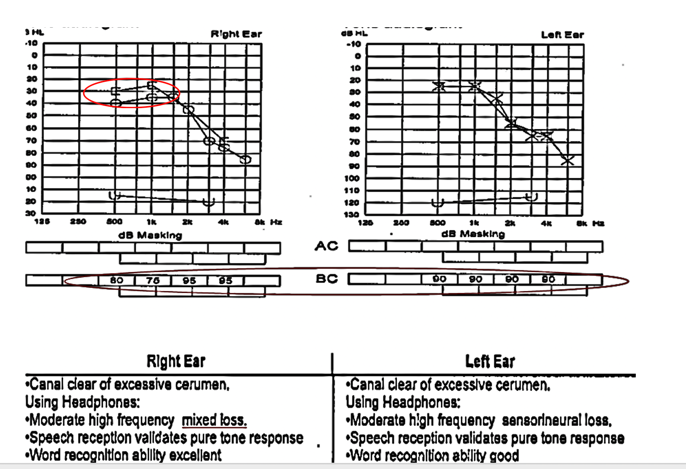

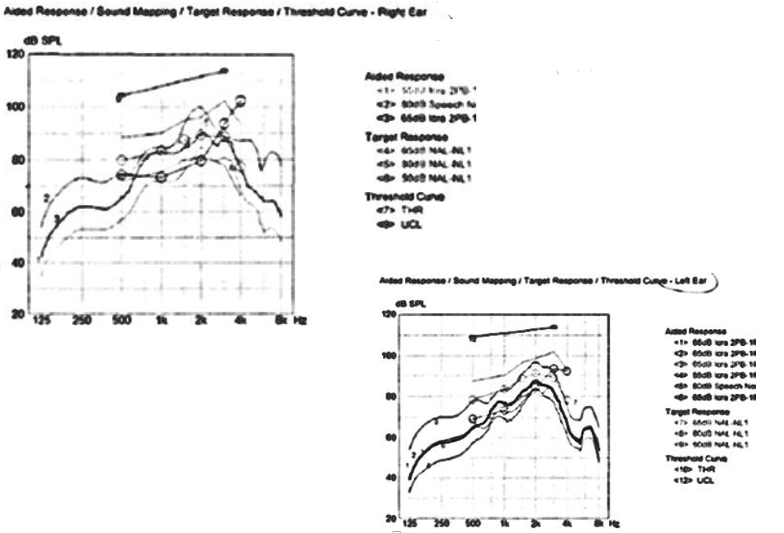

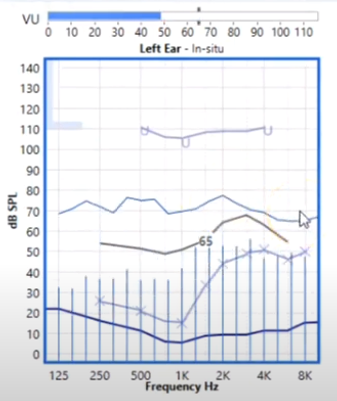

There can be programming errors. In this particular case, this patient was not satisfied with her hearing aids. You can tell that the hearing loss was pretty severe in Figure 18.

Figure 18. Hearing aid case audiogram.

At first, she was fit with mid-level hearing aids. These were then exchanged to high-level because she was dissatisfied. Again, the patient was not happy, stating, "I think that they need to be turned up." She was then not seen for six months. Figure 19 shows the results of the upgraded hearing aids.

Figure 19. REM of exchanged "upgrade" at the time of delivery.

You are looking at UCLs, but there are also some targets of high, medium, and low. These curves are just so-so, but they are certainly not hitting high marks or those lows or mids. These are two different ears showing similar effects. Lo and behold, the patient went to another competing provider who also used real ear. The difference is that they set up the real-ear on the other hearing aids much better. If you remember, there was not a lot of gain in the low frequencies, and it was not hitting up at the target. The competitor had the new hearing aids meeting the targets much better with separation of curves and more amplification in both ears as noted in Figure 20.

Figure 20. REM of other facility HAs.

The patient came back and said, "You never fit me correctly." The husband of this patient also said, "All of her friends say that she hears 80% better than she did with the other hearing aids." That is a huge lesson when we do not program our patients correctly. This is why is it so critical that we pay attention and verify.

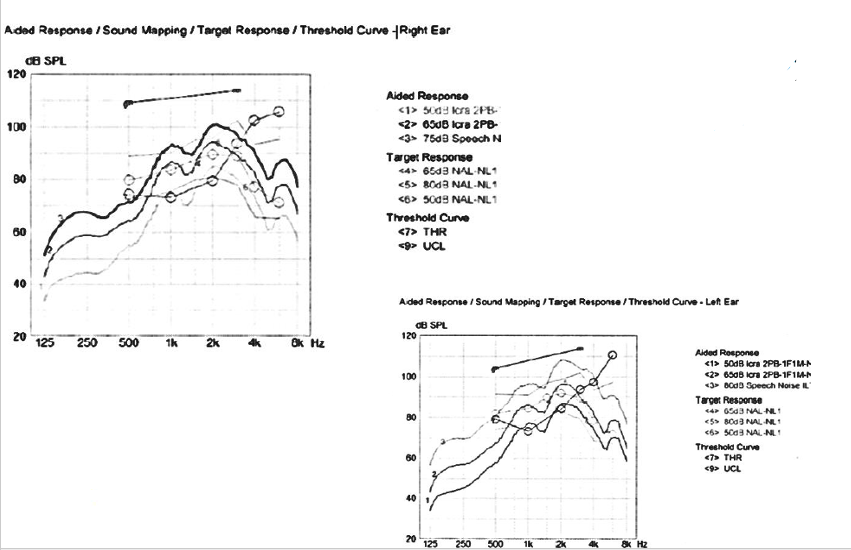

Hearing Aid Verification

- Research continues to show that hearing aids that provide real-ear verified aided speech audibility result in better outcomes than hearing aids that do not provide as much aided speech audibility.

- A study done in 2017 by Leavitt, Bentler, and Flexer showed that 97.7% of subjects showed deviations from the NAL-NL2 in excess of 5 dB in both ears.

Verification is critical. This is the only way we know if we are hitting the targets for that patient or if we need to go down a little bit and enter into acclimatization or whatever tool or feature is on your software. This is where it will automatically keep increasing the gain and output for each of those inputs on a regular basis. Maybe, it is once a week. You get to choose. It could be once a week, every two weeks, or only small increments, like two or three dB. However, it is important that you do that.