Editor's note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Precepting: A VA Perspective, presented by Christine Ulinski, AuD; JR McCoy, AuD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Define what it means to be an effective preceptor and understand the roles of each participant in the preceptor triad.

- Describe the evaluation methods of the resident in a preceptor program.

- Discuss implementation of the principles of an effective preceptorship in the Audiology clinic.

Introduction

The university, the student, and the preceptor each have defined roles and responsibilities. The preceptorship works much better if each of those is aware of their roles and responsibilities. When Dr. Ulinski and I put this together, we wanted to make sure that we talked about things you could do in your clinic tomorrow, next week, or next precepting cycle. We wanted you to be able to take those to the clinic the next day. I hope at the end of the course that you feel that way.

The entire year of 2020 was a challenging year for audiology, dealing with new ways of communicating and seeing our patients, such as taking on VVC, remote programming, and traditional audiology through telehealth. I think the VA did a great job in this area. With 1300 audiologists, there are always some gurus or subject matter experts. I made a lot of phone calls to a friend in Miami saying, how do I do this with the card? Or how do I do that? We incorporated all three of these types of technology to do an excellent job at working with our patients.

Some of our patients have expressed that now this is the way that they prefer to be seen. This was kind of unexpected to me, and I'm sure I'm not the only one. I've had family members of patients tell me their family member was kind of averse to technology, but since I started working with them with remote programming, they communicate with their family all the time. They'll send a Zoom request or something similar to talk about how they're going to cook something. One of the best things to come out of this is that we help some families find new ways to communicate with each other in a challenging time.

COVID started when I was teaching a class on vestibular evaluation. I quickly realized that when the face-to-face interaction was taken away, it would be a challenge for me as a teacher. I had just finished the anatomy and physiology review. We were moving to the hands-on part where I wanted my hands on them to show them quick repositioning movements, how to hold a caloric irrigator, and other important things. Suddenly, the VA said it's probably best for the students not to come to the VA anymore. The university said it's perhaps not best for us to send our students out to externships. As typical with any human behavior, I think that you start to examine things more when all of a sudden you don't have access to them anymore. It made me start thinking, what am I doing good and what am I doing wrong? What's an effective preceptorship and what's not?

Preceptor Red Flags

I know it seems odd to essentially start a talk on an effective preceptorship by talking about who shouldn't supervise students, but recognizing problems before they happen or early in the residency gives you the best chance to ride the ship and have it be as beneficial as possible for everyone involved. I'm not saying everything on this list is a bad thing, and I'm not saying everything on this slide is permanent.

- Inexperienced preceptor

- Resident is a personal friend or relative

- Burnout

- No desire to teach

- Poor self-confidence

- Lack of patience

The preceptor triad that we're going to talk about relies on each triad member knowing their roles and responsibilities. As preceptors, I'm sure you have experienced a time where you were burnt out or didn't have a desire to teach. You may have over-committed to local, state, or national organizations, you may have picked up an extra class, or your schedule at the VA may have become much busier due to staffing issues. I think it's the responsible thing to take yourself off the table for a time, whether it's a semester or a year or whatever you need.

Students pay a lot of money for the privilege of getting clock hours and going to places like the VA and working with veterans. If you're not at a hundred percent, it's not ideal for you to be teaching. I think the university appreciates it. There's always a struggle to find suitable sites for their students. Still, if you're not able at that time because of burnout or no desire to teach, that's going to manifest itself in a lack of patience, and nobody involved will have a good experience with that.

Time can often take care of the inexperienced preceptor who either suffers from a lack of confidence or the equally problematic, I'm usually wrong but I'm never in doubt type of overconfidence. I think it's interesting when you're reading the practice management literature to say, how many years do I need to be in a place before starting a private practice? They say it's generally about five to seven years.

I think to be an effective preceptor, you probably need to have three or four years after the residency before you've got enough experience under your belt to provide a student with that knowledge. Of course, there are caveats involved with that. I've seen students that went through the residency, and a couple of years later, all of a sudden are ready to be good preceptors. Just as often, I've seen audiologists that have worked for 25 years who, because they just don't have a desire to work with students it doesn't turn out well for them. Supervising a resident who is a personal friend or a relative is problematic, and it's probably just best to avoid it.

Resident Red Flags

By drafting and reviewing good preceptorship policies at the beginning of a residency, you can avoid some but not all the problems that you would typically encounter with a resident. These are summarized nicely and fall into four areas by Luhanga and colleagues in 2008. These are nice to watch out for early on in the residency and correct as soon as possible.

- Inability to demonstrate knowledge and skills

- Attitude problems

- Unprofessional behavior

- Poor communication skills

The first one is an inability to demonstrate knowledge or skills. I think students are expected to become more independent over time, and if you're supervising third or fourth years, you don't expect to be teaching basic skills, you expect to be finishing or polishing those students. Residents who demonstrate sloppy behaviors and don't ask questions are often seen as a red flag by supervisors. When you take them not talking to you about questions they have and couple that with repetitive errors or a failure to follow instructions, that's undoubtedly a red flag and something you need to address quickly.

Other red flags are attitude problems such as being overly confident or not receptive to feedback, being indifferent to patients, or being indifferent to their general performance. By that, I mean students should be good self-evaluators to know how they're doing in relation to your expectations and how they're doing with regard to where they should be in their cohort. Those are concerns that need to be corrected as soon as possible as well.

Unprofessional behavior, including poor work ethics such as coming into work late, disappearing throughout the day, being on their cell phones all the time, and then leaving early at the end of the day, are also red flags. You also want to think about if they're lying about interactions with patients or hiding their mistakes.

Lastly is poor communication. This can include being disrespectful to the preceptor, arguing with the preceptor, having inappropriate interactions with the patient, or doing things like eye-rolling during the case history. Eye rolling may not be done maliciously or out of boredom. It may have become a communication strategy for them.

Here's an example. We have a booth that we do VNGs in, so there's a big 55-inch TV in front of the patient. When we're testing hearing, it's turned off. The student, in an attempt to show me their speed and efficiency, is doing tympanograms behind the patient. The patient is trying to make eye contact with him by looking at the TV and seeing what's going on behind them. If that student is rolling their eyes because they can't get a seal on the tympanogram or something, I always tell them, how do you think the patient interprets that when they see it? It's not just me being old, but all people like to have their doctor be face-to-face with them, interact with them, and actively listen to things. How do you think that they perceive an eye roll? I know they don't mean it this way, but I try to correct behaviors like that as soon as I see them because it helps the rest of their career so they won't have that problem keep cropping upon them.

Best Practices

As mentioned, the more work you do on the front end, the better the resident's experience. It's also one of the most effective ways to learn what the residents are coming in with and what your focus on teaching should be. There should be a skills checkoff the first week, or you can review the university skills checkoff. This is done for a couple of reasons. It shows at the end of year one what the students should do with this amount of supervision and at the end of year two and so forth. This helps the student to know where they're at as well. It's also done for potential preceptors in the community. Suppose you haven't taken a student for a while, and you get a call from the university saying a student has expressed an interest in coming into your private practice. In that case, it's for you, the preceptor, to know what the student can do and how much supervision is required. The skills checkoff is good to review initially, at least until you verify that skills competency or witness it in action.

The student should always have the preceptor present or easily accessible should concerns arise. If you're going to step out for a second, tell them when you will be back in. I think all of us that work with students probably progress from, I'm going to be on the same side as the booth as you and doing everything a hundred percent with you, so I'm going to be on the other side of the booth, but I'm going to be listening to you and watching you through the window. There are things that people do differently after that point. I know there are a lot of times when I do hearing aid orientations with a student that after the initial introduction and getting things going, I'll leave the room to look for something and hang out by the door for a second and just listen.

If I hear them go through the hearing aid orientation like we have many times before and I listen to them taking the time to answer the patient's questions correctly, then I may stay out for a while. Many students bloom when you leave them alone for a little bit. So if things are going well, I let it progress. Suppose I start to hear them cutting corners or hear them answer questions about the warranty or whatever incorrectly. In that case, I tend to find whatever I was looking for really quick, and I come back in go over some things that the student had answered wrong or some questions that they had that they didn't know the answer to.

Residents should never be left to perform a procedure that they are uncomfortable or unfamiliar with and certainly jeopardizes patient safety. This includes cerumen removal, repositioning maneuvers in patients with back or neck issues, or making deep earmold impressions, to name a few.

Ideally, they should only perform tasks related to audiology or practice management. Before coming to the VA, I came from a private practice background and have learned that practice management means different things in different situations. If a student is progressing past where their normal competencies are supposed to be and if there's downtime when a patient doesn't show up or something like that, I think it's okay for you to talk about things related to audiologists in terms of how the clinic runs and how to prepare for things. Hence, there are no surprises the next day. When I was working in private practice, I never had a problem talking to interested students about strengthening referrals from ENTs and primary carers in the area or about advertising. Those are things they take classes in at school. If students progress past the point where they need to be in terms of the testing and communication with the patient, then you can go on to more advanced things like that. Everybody knows there's no way to rationalize that a student going to get coffee or running errands for you or something like that is practice management. They are there and paying to be there to learn about audiology and to learn about the particular place where you practice.

Ideally, it's a one-on-one relationship. I'm not saying that just one preceptor should work with just one student. Many places will have a team of preceptors that work with a group of students. I think that's important because you build some trust and rapport over time with that. Those preceptors need to know those particular students' strengths and weaknesses, just like those particular students need to know and trust that preceptor, so they're not anxious about you leaving the room or disappearing or anything like that.,

Characteristics of Effective Preceptors Self Assessment

Up until this point, we've talked about who shouldn't be a preceptor and problems that you can work on if you notice them early with students. If you decide you want to explore being a preceptor, there are a couple of things to think about. One is to do is a self-assessment, such as the Characteristics of Effective Preceptor self-assessment tool that Triple-A has on their website. A two-page questionnaire will ask you questions about things you might not have thought about, such as how effective are you with time management? Are you willing to preplan learning activities before the student gets there that day? Some of this may prompt you to ask questions of experienced preceptors that you know before you decide that this is something you want to do.

Once you've taken the self-evaluation, talk to other preceptors, and you want to volunteer to have a student. On the first day with the student, your average pace and flow of the day will come to a grinding halt. I don't think there's anything unusual about that. No matter what level the student comes in, it takes some time for you two to get to know each other.

In the past, if you had a patient who was 30 minutes late, you might still see them. If you have a student, you might be worried about how the rest of the day would be if you saw the late patient because your day would become compressed. It's not just one particular thing that causes this. I think that students don't do something as fast, but you also spend a little more time reviewing the chart before the patient comes in, taking the case history, testing the patient, counseling them, and doing any follow-up. I think those little increments of time add up. I'm sure we've all had the experience of waiting for the earmold impressions to dry, hearing somebody cough in the waiting room because it's 9:59 and they have a 10 o'clock appointment, and trying to look at your watch without the student, patients, or anybody else seeing you.

You might think, well, of course, I need to see the patient on time, but I want to teach the whole point of me taking on a student. Where's my time for teaching? I will tell you from personal experience, wrapping up things at the end of the day doesn't ever seem to work for me. For example, it's four o'clock and the day's over with. The student and I are both tired, ready to go to our respective homes, and I'm sitting there thinking about the 9:30 patient who I wanted to talk to the student about. Then we had another patient at 10:30 that I wanted to speak to the student about something else. The student is just sitting there shaking their head because they just want to leave. I don't expect them to run out and get into their car and start writing down those little nuggets of information that I gave them so they can remember to put those in practice next week.

The One-Minute Preceptor

A tool like the one-minute preceptor is extremely effective at working with students. This is also called a micro-skills teaching strategy. It is a simple framework for daily teaching during your busy clinic schedule. The article by Neher, Gordon, Meyer, and Stevens on this strategy is listed in the references if you'd like to do further reading on it.

Time management is an essential thing for the student to learn whether they're second, third, or fourth year. They need to have sufficient time to evaluate a patient, but they also need to have a real perspective of the pace and the flow of the clinic and being taught because they're still students. I like this tool because it allows both the preceptor and the student at any point to say, I don't know. At each step in the one-minute preceptor, you're looking at missing knowledge or gaps in knowledge. You're provided with an opportunity during the first couple of steps to reanalyze the situation. It's active learning and doesn't wait for the end of the day to review, and I think that that's key.

The resident may learn something at 8:30 that they can do with the 9:30 patient. You praise them for something at 8:30, and they remember that reinforcement, and then they do it again for the 9:30, or you correct some mistake they make at 8:30, and hopefully, they don't repeat that mistake with the 9:30. They're learning in real-time, and you're not depending on what they know in those last five minutes at the end of the day on Monday to transfer to knowledge that they're going to use the following Monday morning. If you would like to read more about this, there are a lot of papers online that you can look at under micro-skills models of teaching or the one-minute preceptor. Some universities will add a skill so that you might see five, six, or seven skills. If you are a visual learner, there are lots of videos on YouTube and Vimeo demonstrating this. I think a lot of students have done it for student projects. Some of them are funny, but if you're a learner that prefers to learn that way, then there are lots for you to watch out there.

Case Study Using One-Minute Preceptor Method

I'm not going to promise you that in practice, this will take just one minute. I am going to promise you that it requires some practice, but it's you and the resident doing this together, so two people are learning. You might have a little note card handy or something when you're first doing this with a student. After I take time off from working with students and start working with them and doing this method, if I miss a step, sometimes the student will correct me because things don't flow right to them.

- Get a commitment

- Probe for supporting evidence

- Reinforce what was done well

- Give guidance about errors and omissions

- Teach a general principle

- Conclusion

Step One - Get a Commitment

Step one is to get a commitment and get the resident to report on some aspect of the case verbally. It pushes them out of their comfort zone for you to ask a question like, what do you think is going on with this particular patient? If they're correct, it's a chance for positive reinforcement, but you can also continue to do this even if they're correct in the first couple of questions.

I think the reason step one is really important for us as preceptors, which are also teachers, is you aren't just getting a commitment, you're learning about how that particular resident thinks and how they learn. You're learning how they analyze and synthesize information. As a teacher in a traditional classroom, if I have 15 or 20 students, it takes me a little bit of time to learn their learning styles. However, suppose you're working closely with a resident using a tool like the one-minute preceptor. In that case, you can learn that particular student's learning styles exceptionally quickly, especially if you're doing this eight to ten times a day. It doesn't take very many days of doing this before you learn how that student learns.

Step Two - Probe for Supporting Evidence

Step two is to probe for supporting evidence. You commit step one, and now, whether that commitment is correct or flawed is explored. This also exposes the resident who happens to make a lucky guess and pull something out of the air like I think this person has Alice in Wonderland syndrome. You might be thinking, how did they guess that with the limited amount of available information or the additional testing that we need to do? They're kind of exposed because my prompt for this question is what in the case history supports that diagnosis? The lucky guess gets exposed quickly because you're spending time listening to them, not rendering judgment, and finding out how they're learning and processing information to support their guess in question one. You can also ask, what do you think is going on with this patient? This step lets you look at how the student determines the strength of the information available to them to develop their answer to the question.

Step Three - Reinforce What Was Done Well

Step three is to reinforce what was done well. Take care in this step not just to say good job because they don't know what they've done that was a good job. Was it a good job that I didn't hit my head on the booth when I was coming out, or did I do something particularly good that I need to transfer to the next patient?

Always try to be specific with this and say our case history only asked a couple of questions about their tinnitus. It was really good that you asked for additional information about that. Now we can use that information to go forward a different way with this patient if we're treating them just for their tinnitus.

Step Four - Give Guidance About Errors and Omissions

Step four is to give guidance about errors and omissions. It's important to tell them what they did right just as it is essential to tell them what they need improvement on. You're promoting the continual expansion of knowledge, exposing weaknesses so you know what to work on. If you're like me and you loathe to criticize anybody, especially a student that you see trying or struggling, you can blunt your criticism by changing how you word things. You can say it is preferred to do things this way instead of saying it's wrong to do things this way. You're doing this over and over through the day, so again, try to be as positive as you can be unless you see repetitive errors.

Step Five - Teach a General Principle

I think there's a tendency, especially in the VA, to over-generalize. For example, if you have a 7:30, 8:30, and 9:30 hearing test that you're going to be working with that resident on you might think, these people are probably going to present with similar complaints, they're probably going to talk to me about family complaints that are very similar, they may have a similar configuration to their hearing loss, and the treatment that we do with them may be very similar. They may just have a similar thing in common of noise exposure that kind of makes all those things true.

Often, I think the preceptor falls into a trap because they think I'm not teaching anything profound. Shouldn't everything that I teach the student be profound? The answer to that is no. Suppose eight to 10 times a day, or however many patients you see. You're teaching little bits of knowledge to the student for each of those patients. In that case, that's the experience that that audiologist or that future audiologist gets that makes them become well-rounded and teaches them things. Be specific in terms of teaching them something, even if it's little. It can be something as little as the reason I looked at her phone because she has an Android, and I wanted to make sure she has software that's 11.0 or higher. That may lead me in a particular direction in picking a hearing aid. It could be explaining the reason I chose to do an EPLI instead of a Saman. It doesn't have to be something profound. It just has to be little nuggets of knowledge that they remember from patient to patient and can recall later.

Step Six - Conclusion

There's a saying in golf, think long, think wrong. I am a classic over-thinker, and I overanalyze things, but when using the one-minute preceptor with a student, it's my responsibility to end things. This last step of a conclusion is an opportunity to talk with the student about what their guess was, what their commitment was in step one, what they think is going on, the evidence they provided for that, and what they did well. Often I will say I specifically like this question that you asked in the case history. Thinking back to step four, tell the student to remember to do this for the next patient, or I'm going to teach you something that you can take to this next patient or use for the rest of the day. This is the time to wrap things up and go to the next patient.

Case Study

Now, I don't want you to get out your stopwatches or anything and time me to see if I'm telling the truth of whether this can be a minute or not. I wanted to show you how this fits together, so I came up with a pretty common patient that we would see, especially if you see balance patients.

Our patient is a 42-year-old male with motion provoked vertigo that lasts seconds or under a minute. He denies any type of prodromes, such as he doesn't have an increase in tinnitus, he doesn't have a migraine, headache, or anything like that before that happens. There's no increase in aural fullness. He just has a high-frequency hearing loss, and he has no tinnitus and a history of noise exposure.

Step one. After doing some testing, and while the student is testing, if possible, ask the student, what do you think is going on with this patient? Hopefully, they say, I'm thinking this patient has BPPV.

Step two, what in the patient's history old you that? Hopefully, your student will answer in a way such as I asked him about medications that he may have taken for his dizziness, and he said nothing's helped him. It looks like he has a symmetrical loss, he has no complaints of tinnitus, and there's nothing that happens before the event other than him moving, so all those things take some possible other problems off the table. I'm left with a patient who says, I move a particular direction or a particular speed, and it causes this. I could probably show you right here what causes it. When I get dizzy, it feels like I'm turning, and then it just takes about 30, 40 seconds for me to feel better. That's what the student was basing that on. You've asked them to look at this additional evidence and provide a justification, and I think that would be a good justification moving forward or until you get more information.

Step three, reinforce what was done well. You could say something like, you did a great job asking additional questions. I especially like the question you asked about if your spouse or a friend has ever witnessed one of these events, and have they said anything about your eyes jumping around or anything like that? That was an excellent question to ask that lends support to a particular direction that we're going.

Step four, give guidance about errors and omissions. You could say something like, as a follow-up when you were asking about head trauma, if you suspect that we're going to do something about BPPV, go ahead and ask the patient about head and neck injuries. I have found that sometimes when I ask that question at the beginning and then circle back to it at the end, I may get a different answer. I asked that question several times, so you did well there. The other thing is, I know you're excited that this patient may have BPPV, which is something we can treat today, and he can walk out of here feeling a lot better and be significantly better a couple of weeks from now but the patient also had hearing loss. Just because his chief complaint was dizziness, which is what brought him here, remember we tested his hearing before that, and we haven't talked to him about how the hearing loss affects him. Just because they come in with one complaint doesn't mean that we shouldn't treat all of their complaints, so just remember that going forward.

When trying to teach them something you could say, I noticed compared to you, this patient is very tall or is much heavier than you, so I'm going to teach you a different way to do the Dix-Hallpike. There is a different place to stand where you'll be more comfortable and feel like you support him better, and it won't end up throwing you across the room whenever he moves into a different position.

Then step six is the wrap-up. You did an excellent job with the BPPV, and I appreciate how you supported your diagnosis. I like the extra questions you asked during the case history to strengthen the direction we were going. Remember to address the whole patient, not just what their chief complaint was. Also, remember that if you have a patient that's a lot larger than you or a lot heavier than you, you can do the Dix-Hallpike a different way to where it maybe doesn't put that much pressure on you or him, and now let's move on to the next patient.

I promise you, it can be quick. Again, the more you do it with the resident, the easier it becomes. It doesn't take but a couple of days for you and the resident to both be in sync when you're doing this.

Roles and Responsibilities Create the Preceptor Triad

Before we transition to Dr. Ulinski's portion, I just wanted to mention the idea of the preceptor triad again. This was described by Yonge & Myrick as noted in your references. There are also some university studies that I thought did an excellent job of explaining. As I mentioned before, everybody in this triad has their roles and responsibilities. If you do what you're supposed to and become responsible for only the things that you know that you need to be responsible for, it gives us the best chance of this preceptorship being effective.

Resident Responsibilities

So what's the resident responsible for?

- Professional

- Reliable

- Accountable

- Self-evaluator

As mentioned, the resident needs to know from the beginning that you expect them to be professional in terms of how they dress, their communication with the patient, and their attitude. You want them to be reliable in showing up and being ready to see patients and not disappearing. You expect them to be accountable and a self-evaluator. Those things kind of go hand in hand. They need to admit the mistakes that they've made, and they need to understand where they're at in relation to where you think they should be.

Preceptor Role

- Role model

- Teacher

- Facilitator

- Guide

- Evaluator

- Safety net

- Being authentic

When I went to the University of Kansas, I was able to get an externship at the Kansas City VA, where I had not one but three role models that provided me with as much information as I learned in the classroom. They sought out learning opportunities for me, corrected me when I was wrong, gave me feedback when I was doing things correctly, was a safety net for me when I got in over my head, and were authentic. They talked to me about their career development pitfalls or problems that they had come across. In sum, they did everything on this list.

I will sometimes notice whenever I'm talking to a patient, interacting with a colleague, or thinking about how I care for patients, I almost feel like I'm mimicking the behavior of those three people at the Kansas City VA. I say that in a sense that I don't ever want you to underestimate how important you are as a preceptor. I'm mimicking behavior from somebody that I saw 20 years ago. Some students could do the same thing for you, so you want to be at your best every day. You want to show them how we'll go out of our way to do anything we can to help our patients.

University or Faculty Role

- Facilitator of clinical learning experiences

- Evaluator

- Overall responsible party for student learning

- Resource for student and preceptor

Last is the university or faculty role. Some things fall onto the shoulders of the university. They are the overall evaluator and facilitators for the student's learning experience. I've worked with first years at a university clinic and have seen students geared toward pediatrics. Those students will say they want to cherry pick or grab the peds kids cases. Their first externship site might be a children's hospital. Their second one might be a long-term training ship through a group that works with implants with young kids. Then because of how much experience they have in pediatrics and how well they know people in the pediatric audiology community, they get the fourth year residency at the children's hospital only to graduate and have the available jobs, whether VA or private practice jobs.

The university prepares the whole student. They don't just take classes in pediatric audiology. They teach them to care for pediatric through geriatric people with hearing and balance problems. They're responsible for the whole learning experience by making sure you have a diverse clinical practicum experience.

Last, as the resource for the student and the preceptor, sometimes they may be a mediator for problems encountered in the relationship. If you're a new preceptor, you can always talk to the university about how many times people are evaluating them throughout that first semester or how long they will be with me. I have had questions about grading, such as how do I assign a letter grade? Can you give me some help with that? The university should be there to help you with those things. My portion of the lecture talked about things as a classroom, a pie in the sky type of thing, but Dr.Ulinski will talk about an actual program, so I'll turn it over to her.

VA Organizations

We're shifting gears a little bit here to talk about some of the considerations and practicalities as you put together an externship program. We have a saying in VA: if you've seen one VA, you have seen one VA. Each VA facility operates fairly independently. Today, I'm just sharing my clinic's experience with the externs at Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital and things that I have learned about the externship process over the years. As Dr. McCoy stated earlier, we're speaking for ourselves, not VA but for all the individuality between sites. Because the VA is a large organization, there are actual parameters to ensure the veteran has the best patient experience possible and the externs are educated appropriately.

Considerations in Structuring an Externship Program

As you're building your program, you want to consider why you want to take an extern. What are you going to be offering the extern? Do you have a good variety in the types of patients you see or variety in the types of audiology practice? Are you able to expose the extern to a variety of clinical styles? At Hines, we have structured our externship program to work with a team of two preceptors for a set rotation, usually about four months at a time, so they rotate three times throughout the year. Each rotation emphasizes an audiology specialty, whether it be tinnitus, vestibular, auditory processing disorders, or cochlear implants. This allows the extern to stretch in that area of practice and reinforce what they are learning.

Repetition is a great way to solidify skills. Additionally, the externs are exposed to everyday practice such as audiologic evaluations, hearing aid fittings and follow-ups, and telehealth, both traditional and using remote care. The externs are assigned to spend time in our hearing aid repair clinic, quick 15 minute appointments where you triage and fix aids in-house if possible. This teaches a skillset of how to control the time flow of your appointment and build hearing aid skills. The students help process the mail for aids mailed in from veterans, process new aids and repaired aids from the manufacturer, get aids mailed back out to veterans from a repair, or help with virtual hearing aid fittings. There are always special projects to be worked on.

This year, we're building our inpatient practice, and the externs are actively participating in that by going to the floor to see our patients, taking pocket talkers up to those who need it, et cetera. Keeping the externs with the two preceptors at a time but then rotating among the staff throughout the year exposes the extern to a variety of styles of practice while allowing for consistent expectations of the student and from the student. By knowing which preceptor they are working with on a particular day or time, the extern can prepare ahead of time for the encounter. During COVID, like most clinics, we weren't seeing as many patients. We're pretty much back to full capacity, so it is a busy pace.

Our ultimate goal for the externs is for them to develop solid clinical judgment, the ability to adapt to the situation and thrive in any clinical setting. Our externs also get exposed to a variety of patients. There are patients with traditional sensory neural hearing loss and hearing aid patients, but our facility also has a blind rehabilitation center where the veterans are dual sensory loss patients. The approach to fitting a blind patient with a hearing aid is different from a sighted patient with special considerations in the hearing aid selection and how you teach the veteran to use the hearing aids successfully. Hines also has an extended care center where veterans tend to be older and more infirm, requiring a different approach.

Additionally, our department provides audiologic support for the Hines ENT clinic, which runs every day of the week. Many of our tinnitus patients also deal with mental health issues, which allows for collaboration between the services. Many APD patients have had traumatic brain injuries, which is yet another approach to patient care.

Every facility will handle how you add an extern to your practice differently. The larger the institution, the more formal things tend to be. I would advise you to reach out to your facility's legal counsel or education department, if there is one, to verify any requirements that need to be met.

The VA is the largest clinical educator of audiologists in the country, and it is one of our core missions to educate future health care providers. There are several formal agreements that need to occur to onboard an extern. An affiliation agreement must be established between each site and the university. This requires signatures from both the education department at Hines and the provost of the university of the extern, which takes time to process. Fortunately, now these agreements are for ten years, which makes life a bit easier.

The externs will process through human resources, which means a lot of paperwork needs to be completed and turned in at set times and dates prior to the day the extern arrives. There's also paperwork that must be completed for the education department. Most importantly, getting the extern and set up with OINT to have access to NOAA, the electronic medical records or ordering system, email, et cetera. Check with your institution's legal department or your legal representative on needs or requirements of your site.

Health Paperwork and Concerns

Especially in this COVID era, health considerations are our top priority. How do you ensure your patients, staff, and externs are safe, and how do you document that you have done so? VA has a set health form, the Trainee Qualifications, and Credentials Verification Letter, which we abbreviate TQCVL. The university completes this form to detail that the extern or intern has met basic health requirements. This includes TB testing, COVID vaccination status, traditional vaccination status, et cetera. You will want to verify how and where your institutions would like this information recorded. At Hines, we have to submit this information to the chief of staff's office and maintain the information in the student's folder for ready access.

Both the university and extern should be aware of your site's PPE and infection control policies. Is your facility able to provide PPE for the extern, or are they expected to bring their own? Should an extern fall ill, what are your policies for notification, et cetera? If they are exposed to COVID while at your facility, how will that be handled? Does your facility provide COVID testing? Are there policies for returning to the practice after an illness? There are just more details to consider and document these days. In my situation, we are fortunate that if an extern is exposed to COVID, they are eligible for testing via occupational health, regardless of whether they are a funded extern or not.

Level of Supervision Provided

I believe that supervision is a critical component of building a successful externship program. Hines has received feedback from externs over the years that they appreciate the level of supervision and support that they received and that that was a key reason why they selected our facility. Again, with the VA being a large institution, policies and procedures are set for how a non-licensed individual interacts with a veteran or family member. Below are details of our policies and procedures for your review.

2. Outpatient Clinic

The type of patient, inpatient versus outpatient, new patient versus experienced patient, the level of complexity of the appointment, and the skill level of the extern will factor into the degree of supervision you should be providing for that encounter. As the preceptor, you are responsible for that patient's experience. Externs are acting under the license of their preceptor and should be monitored as such. There are different levels of supervision expected based on a student's level, as seen below in excerpts from our policies and procedures. A younger student with less experience will need more direct supervision and interaction from the preceptor than an extern finishing up their externship year.

a. Supervising Graduate Students. The electronic health record must demonstrate the preceptor personally performed, or performed with the assistance of a trainee, all procedures and services. Graduate students engaged in masters and doctoral clinical rotations must be personally supervised at all times.

Graduated Progression of Responsibility

1. As part of a training program, trainees earn progressive responsibility for the care of Veterans. The determination of a trainee's ability to provide care to Veterans without a preceptor physically present, or to act in a teaching capacity, is based on documented evaluation of the trainee's clinical experience, judgment, knowledge, and technical skill.

2. Trainees must comply with state law in obtaining provisional, interim, or temporary licenses or obtaining permits or registration from licensing boards, where applicable. However, the fact that a trainee has a license does not change the requirements for supervision.

This next part of the graduated progression of responsibility goes through what the audiologists involved with the program and training are accountable for.

3. Ultimately, the preceptor determines which activities the trainee must be allowed to perform within the context of assigned levels of responsibility. The overriding consideration in determining assigned levels of responsibility shall be safe and effective care of the Veteran

4. The Education Coordinator must define the levels of responsibilities, in consultation with preceptor(s), by preparing a description of the types of clinical activities trainees may perform. These activities shall be coordinated with the educational affiliate and individual needs of the trainee. The Education Coordinator must make this list of graduated levels of responsibility available to other staff. The Education Coordinator must include a specific statement identifying the evidence on which such an assignment is made and any exceptions for individual trainees, as applicable.

5. Candidates for professional degrees must be educated and supervised within a specific educational curriculum determined by the college or university. The determination of a student's ability to provide care to patients shall depend upon documented evaluation of the student's clinical experience, judgment, knowledge, and technical skills. The supervision of students is the responsibility of VHA staff audiologists or speech-language pathologists.

How to Document

Orientation to Your Site

When welcoming an extern to your facility, orienting them to your site is a good idea. This is the perfect time to establish your expectations and introduce the extern to the culture of your clinic. When do you expect the extern to arrive, leave and how do you want them to interact with patients? You have to orient them to all your electronic systems. For many VA's, this will include getting their PIV card to access the computers, learning the electronic medical record system, learning the ordering system, et cetera.

At Hines, we have developed a formal handout that we go through with all of our trainees that spells all of this out. That way, everyone is on the same page. We've included details about the history of the VA and audiology in the VA. The handout covers dress code requirements that are in place, and we give them a tour to cover the physical orientation of the clinic, showing them all the areas where they will be working. Additionally, we also have the externs complete the Student Self-Assessment of Clinical Skills from the University of Pittsburgh to be shared with their preceptor during the first week. We have found this an excellent way to reflect on where a student might be in their learning and what areas they need to focus on. This is a leaping-off point to discussing needs and expectations.

Then there are the day-to-day factors that go into welcoming any newcomer to your facility. Where's the cafeteria? Do you have a refrigerator in your area for lunch? Where are they able to park in relation to your clinic? What are your PPE and infection control policies? Does this individual have any special needs in terms of PPE? What duties are being expected of the extern? Provide contact information of the preceptors and externs so in case of an emergency, and everyone can remain readily in contact. This is all in that written booklet that we go through with the externs during the first week, that way, there's always something to reference.

Documentation

Documentation of the electronic medical record is part of the extern's training. As seen below, our handbook notes the appropriate mechanisms for documented patient encounters where the extern is present.

a. Documentation of supervision must be entered into the preceptor's electronic health record (CPRS) or reflected within the trainee's progress note or other appropriate entries in the electronic health record. NOTE: For this Handbook, the term preceptor is synonymous with supervising practitioner.

b. Types of allowable documentation are:

(a) Independent progress note or other entry into the electronic health record by the preceptor.

(b) Addendum to the trainee's progress note by the preceptor

Example: Jane Smith, Audiology Trainee, was present and actively participated in this encounter

At Hines, the trainees or externs are not allowed to document independently. The notes are written ultimately by the provider of record, but it is documented in the note that Jane Smith, audiology trainee, was present and actively participated in this encounter. We also provide a template for notes to help ensure standardization among providers.

Billing

One of the reasons our notes are written in this manner pertains to billing. The externs are not assigned a person class and cannot submit for workload. The preceptor is ultimately responsible for the veteran's encounter and all aspects of care, including billing. To be given credit for workload that has been completed, the encounter must be credited to the preceptor. At Hines, we routinely go through appropriate coding to ensure the externs are learning to code properly. The information below further details that services performed independently by students or externs cannot be billed. This would be regardless of provisional licensure status. Illinois doesn't have provisional licenses, so that's not something we've had to deal with.

a. Person Class designation is restricted to individuals who are identified as providers and whose services are billable. The preceptor is considered the provider of record, and their Person Class is used for billing purposes. With a few exceptions, a person class may not be assigned to trainees. In no instance shall assignment of a Person Class imply in any way that the trainee is credentialed to function independently. Any workload or encounters with the trainee entered will not transmit to the Financial Services Center due to lack of valid person class. Instead, patient encounters must be credited to the preceptor.

b. Trainees must have an appropriate User Class. The designation interacts with the Authorization/ Subscription Utility (ASU) to allow access to the electronic health record. VHA business rules do not prevent trainees from being assigned a user class.

c. Services performed by students must not be billed.

d. Only services performed by a credentialed provider must be billed.

e. Only documentation by the credentialed provider must be used for billing purposes.

f. Bills are issued only if there is progress note documentation of provider face to face involvement in addition to the Patient Care Encounter

Feedback

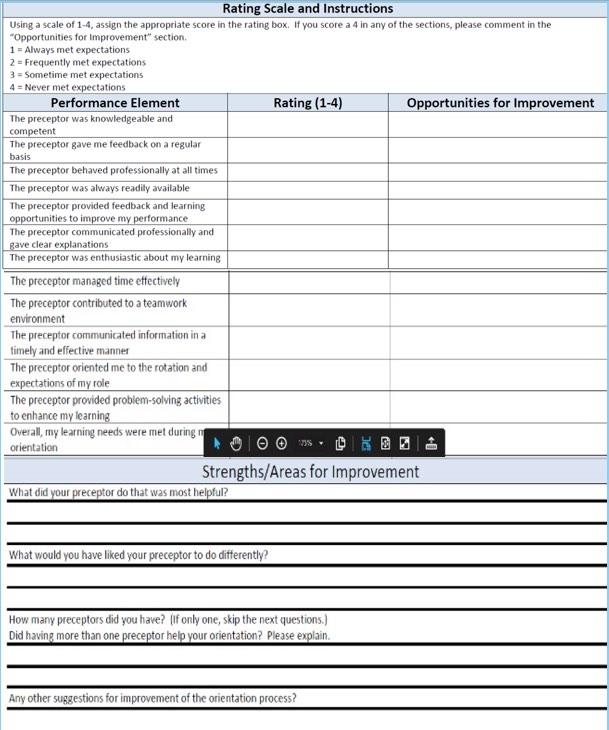

The form seen in Figure 1 is adapted from nursing, but I thought it hit a lot of the points we wanted. There's a one to four rating scale from one, always met expectations, to four, never met expectations.

Figure 1. Rating scale for feedback from an extern. Click here to view this image larger in a PDF format.

Items on the form include:

- The preceptor was knowledgeable and competent.

- The preceptor provided feedback and learning opportunities to improve my performance.

- The preceptor communicated professionally and gave clear expectations.

- The preceptor contributed to a teamwork environment.

- The preceptor oriented me to the rotation and expectations of my role.

- Overall, my learning needs were met during this rotation.

There's also a space for free-field responses, which can be tailored to the specific preceptor and allow feedback about the orientation process. What did your preceptor do that was most helpful? What would you have liked your preceptor to do differently?

The Audiology Clinical Education Network is a group working to standardize the externship process across the profession. Right now, approximately a hundred plus externships sites are participating. Some VA, some major medical centers, some university clinics, some private practice, et cetera. One of the first projects was setting a timeline for the externship application and selection process, which is going on right now. They have also created a questionnaire for the externs to provide feedback to the site. Please note, this is very much a work in progress, but I wanted to take this opportunity to share it with you. It takes a little bit of a different format than the other form. Below you can see a rating scale, this time from one, completely disagree, to six, completely agree. They cover orientation and expectations along with goal setting.

I am reflecting on: ____ the site ___ a specific preceptor ___ all of my preceptors

I am completing this: ___at the start of a placement ___mid-placement ___ end of placement

Scoring: 1: Completely Disagree 2: Mostly Disagree 3: Somewhat Disagree 4: Somewhat Agree 5: Mostly Agree 6: Completely Agree

- I was provided with orientation to the clinic, and appropriate avenues to direct my questions or concerns.

- The expectations for patient populations and clinical experiences were clearly outlined prior to the start of my placement

- My preceptor(s) establishes and maintains an effective working relationship with me.

- My preceptor(s) assisted me in setting goals and outlined expectations at the outset of my rotation.

- My preceptor(s) provided me with consistent feedback throughout my rotation.

- My preceptor(s) provided and demonstrated patient care in an ethical manner consistent with standards laid out by the site and professional organizations.

- My preceptor(s) fostered independence and provided supervision commensurate with my skill level.

- My preceptor(s) was able to demonstrate and explain clinical decision-making using evidence-based practice.

- My preceptor(s) was engaged and enthusiastic about my learning experience.

- My preceptor(s) provided me with reasonable time to complete all of my clinical responsibilities.

- Please list two or three things you feel this preceptor could do better or improve upon.

- Please indicate two or three things that you found most helpful in working with your preceptor.

- Suggestions for how the supervisor could improve their mentorship style.

- Any other comments you would like to share at this time?

Feedback is very much a two-way street that allows the externs the chance to provide feedback for their preceptors and the site. It will strengthen your program. All of these different considerations for low logistics of onboarding an extern from health status, to supervision and documentation, to the orientation process, and feedback between the external site go into creating and maintaining a successful externship program.

Citation

Ulinski, C. & McCoy, J.R. (2021). Precepting: a VA perspective. AudiologyOnline, Article 28057. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com