Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live seminar. Download supplemental course materials.

Introduction

It’s hard for me to imagine now that at one time our profession was faced with a battle - whether or not to universalize newborn hearing screening. Here’s a little history review. Back in 1994, the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing released a position statement (JCIH, 1995), which was a proposal that urged facilities with infant hearing programs to develop protocols to universalize the newborn hearing screening process. In addition to details about the newborn hearing screening process itself and how to go about performing the screening, there were specific recommendations for early intervention and providing family support when hearing loss is the outcome. It is my understanding that there was much debate about whether or not to universalize newborn hearing screening because of the supposed disruption in bonding that may occur if we allow a means to identify hearing loss at the beginning of one’s life.

The debate was about the fact that during this time, the newborn is meeting his or her family for the first time and that family is forming bonds and getting to know their new child.

This was a valid concern, because as we know, universal newborn hearing screening allows audiologists to inform parents about what is, essentially, a developmental emergency. I’m confident that as audiologists we all realize the benefits to early diagnosis and early access to sound. As audiologists, we have witnessed firsthand the positive outcomes that are a direct result of identifying hearing loss at birth. However, I’d like you to imagine, if you will, the scene of an emergency situation.

Do you picture chaos, perhaps an ambulance racing with lights flashing or a sense of panic? Imagine delivering the news about this developmental emergency to unsuspecting parents who had no way to plan for the emergency or its aftermath. It’s no wonder that there were whole sections of the Joint Committee’s position statement that included the need to provide support for the family who is now dealing with basically an emergency situation. Recommendations for family support are historically well-documented. If we look back even further to the Joint Committee’s 1990 position statement (JCIH, 1991), which, at that time, was only recommending newborn hearing screening for babies that fell in the high-risk population, even back then, that position statement included recommendations regarding family support. Those recommendations included: providing the family with education, counseling and guidance, including home visits and parent support groups; providing families with information and child management skills; and giving emotional support consistent with the needs of the family and their culture (JCIH, 1991).

Historically, family support has been recognized as an important factor when identifying a developmental emergency at the very beginning of one’s life. However, as the profession moved forward with a very strong focus on the implementation of the actual hearing screening, our goal at that time was to try to get newborn hearing screening in all 50 states. We wanted this done universally, and that was the focus, also including the habilitation of identified hearing loss at birth. The focus has mostly been on the child, but not necessarily the parents, despite the fact that we all know how critical the parents’ role is in the child’s outcome.

In 2010, the universal newborn hearing screening programs were evaluated, and the results were very nicely summarized in a paper by Shanna Shulman and colleagues. The evaluation found that newborn hearing screening has successfully been implemented and is now universalized, which is great. However, improvement is still needed in specific areas. Mainly, there is a lack of family support in most states. In this evaluation, 38 states estimated that only 40 percent of families with children who have hearing loss are linked up with a support program. One-third of the universal newborn hearing screening providers had no knowledge about family support in their local area.

Essentially, this paper (Shulman, Besculides, Saltzman, Ireys, White, et al., 2010) confirms that we are lacking an emergency assistance plan, or at least a universal emergency assistance plan. We have established this great means to identify a developmental emergency at birth, but we have inconsistent availability of emergency assistance afterwards. The identifying of the emergency has been universalized, but I would like to say that now it’s time to universalize the 9-1-1 system. In order for something to become universalized, it has to be both effective and efficient. If you think about the newborn hearing screening process itself, the test has to be effective with minimal false positives, minimal false negatives, and it also has to be cost effective and efficient. The hearing screening has to be quick and simple in order to screen thousands and thousands of babies each year. We would never have been able to universalize that process until the effectiveness and efficiency were accomplished first.

Step 1: Identify Parent Needs

As a profession and as advocates of the universal newborn hearing screening process, we must develop an effective and efficient family support system protocol that can be universalized. Step one to providing parent support is to find exactly what it is that parents need, and I like to say that this can be easily accomplished through conducting simple surveys. Specific parent needs are going to vary based on currently-available, local resources to the parents and also on the stage of development of the child. As the child develops and grows, the needs of the parents are going to change over time and also with current technology.

Regional and social variances, including cultural differences, are all going to impact parent needs. I have been surveying parents in the area where I practice since I started a parent support group in Massachusetts called “Hear My Dreams” in 2007. At first, I just used informal paper and pencil surveys to gather basic information about forming the support group. I gathered information about how often parents wanted to meet, what time of day was good for the parents, and what information specifically did they need. More recently, I have utilized SurveyMonkey, as SurveyMonkey is pretty simple. It’s inexpensive. It’s anonymous, and people respond to it. A lot of what I’m going to share with you today was gathered through these simple surveys, so let’s go ahead and move forward with that.

I can tell you that the parent of a child with hearing loss likely has normal hearing. Of the 80 parent respondents of my most recent survey, 68 were mothers, 10 were fathers, 1 was a female guardian, 1 was a male guardian, and 98 percent reported that they have normal hearing. And this is consistent with reports from several sources, including the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD; 2013), who consistently report that over 95 percent of children with hearing loss have two normal-hearing parents. The parent of a child with hearing loss has no preparation for this developmental emergency. It is completely unexpected. The survey question I asked was, “When you first learned of your child’s hearing loss, did you expect it?” Ninety-three percent of parents reported that they were not expecting this diagnosis at all. It was a complete surprise.

At the moment that they learn of their child’s hearing loss, parents have no idea who their peers are. The survey question was, “When you first learned your child had hearing loss, did you already know at that time another parent of a child with hearing loss?” Ninety percent had never met another parent of a child with hearing loss before that moment. And at the moment that they first learned of their baby’s hearing loss, they had no clue how to raise a child with hearing loss. Parents lack the education and information needed to do so. The survey question was, “At the time of diagnosis, did you feel fully equipped with the knowledge of how to raise a child with hearing loss?” One-hundred percent of the respondents said no, they had no idea. They felt they did not have that knowledge and information needed on how to raise their child with hearing loss.

Although they may not express their emotions at the time, if you ask a parent later on, this is how they reportedly felt the moment that they were given the diagnosis that their child had hearing loss: crushed, overwhelmed, shocked, confused, devastated. They ask, “What did I do wrong?” There’s something about that moment, that turning point when parents first learn that their new baby has hearing loss. There are deep emotions that are connected to that memory, or it seems that those emotions never really go away. Ask any parent of a child with hearing loss to tell you how they felt that moment that the audiologist told them that their new baby had a hearing loss.

To summarize, the answer to our first question, “Who is the parent?” The parent is someone with normal hearing, who did not expect this diagnosis, who does not know another parent of a child with hearing loss, who lacks the education and information needed to raise a child with hearing loss and who has a strong emotional reaction to the diagnosis of hearing loss. In other words, there has been a disturbance in life as they knew it, and with the unexpected diagnosis of their child’s hearing loss, parents now have psychosocial needs, psychoeducational needs and psychoemotional needs that must be met.

Step 2: Address Parent Needs

Now that we’ve identified these specific needs, how do we best go about addressing them? How do families want to find their peers? How do they want to obtain information that they need about raising their child with hearing loss? How do they want to address their emotional needs? I think it’s pretty common for audiologists, at least here in Massachusetts, to hand parents a folder of information at the time permanent hearing loss is first diagnosed.

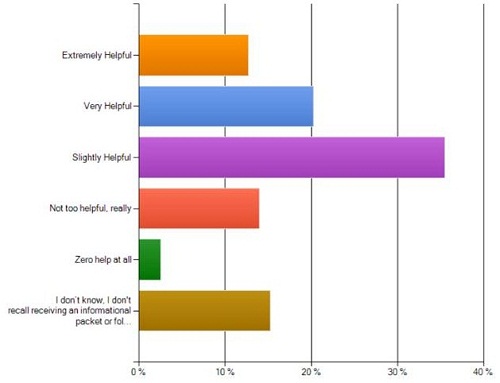

In the survey, the question was, “When your child was diagnosed with hearing loss, you may have received written paperwork in a folder. How helpful was this informational folder to you?” Based on the survey, most parents found this informational packet only slightly helpful (Figure 1). In Massachusetts, when children who do not pass the newborn hearing screening get a confirmed diagnosis of permanent hearing loss, they receive a phone call from a parent outreach specialist who works for the Universal Newborn Hearing Screening Program, employed by the Department of Public Health.

Figure 1. How helpful was written paperwork/informational folder?

This parent outreach specialist will speak with the families throughout the diagnostic process. They ensure that the family is connected with an early intervention program. They provide the family information about hearing loss, and then they share their own experience as a parent of a child with hearing loss.

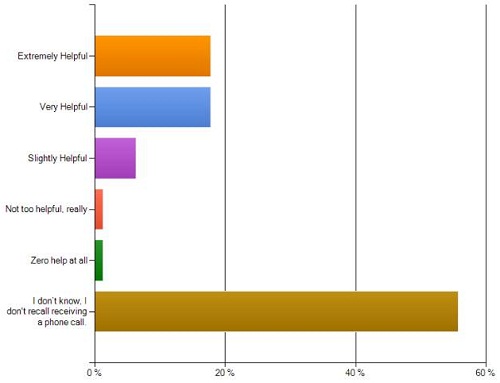

The next question here was, “After your child was found to have hearing loss, you may have received a phone call from another parent of a child with hearing loss. How helpful was this phone call to you?” For many families, this phone call is extremely helpful, but, unfortunately, when this phone call comes in, it is often soon after the parents just got home or just found out about their child’s hearing loss, and many parents do not even recall getting a phone call, which indicates that this call alone may not be enough to address parent needs (Figure 2).

Figure 2. How helpful was the parent phone call?

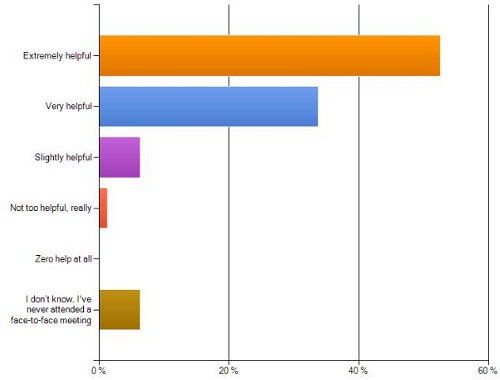

The next question asked on the survey was, “In regard to family support, how helpful is it that there are face-to-face support group meetings available to you?” From this, it looks like the face-to-face support groups that meet in person were extremely helpful (Figure 3).

Figure 3. How helpful are face-to-face support group meetings?

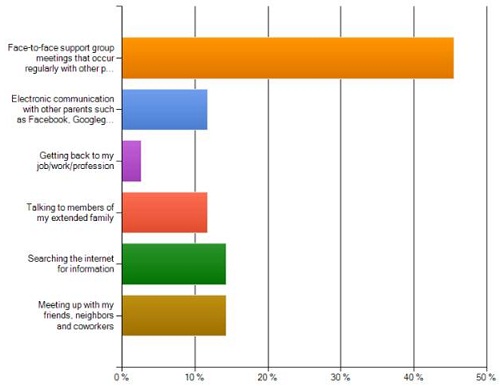

When comparing the written information and the parent outreach specialist phone call to support group meetings that meet in person on a regular basis, parents choose the support group venue to best address their needs. They choose support groups over other types of self-help. Here the question was, “Other than your child’s professional specialists, where do you find the most support to address your needs as a parent?” Most parents chose face-to-face support groups over other self-help support, such as electronic communications like Facebook or Google Groups, getting back to the job, talking to members of extended family, or searching the Internet and meeting up with friends, families and coworkers (Figure 4). The face-to-face support groups take the lead. Parents are looking for their peers, and their life prior to a child with hearing loss did not have those peers. They are looking for their new peers.

Figure 4. Where do you find the most support to address your needs?

When asked, “Would you recommend a support group that meets face-to-face on a regular basis to other parents of children with hearing loss?” 100 percent of the respondents said, “Yes.”

Support Groups

To summarize, parents wish to have their needs met in person in a group setting with other parents who meet on a regular basis. So, how do we best accomplish this? Well, let’s start with the face-to-face part. There are a few simple, but key, factors needed to establish an effective face-to-face support group that meets on a regular basis. First and foremost, you have to determine a location.

Find a place that will donate use of space for free, if possible. Remember that in order to be universal, we have to be efficient, and many places, like churches, libraries, and medical facilities have meeting space available for support groups. Preferably, these meetings would take place in an accessible, central location, and once you have determined a location, then you’re ready to move on to the next step, which is determining time and frequency. Remember that many parents work during the day. Therefore, you may want to pick a time during the evenings after most children have gone to bed.

If you hold a meeting every other month, that’s six times a year. Often, parents can prearrange for childcare in order to attend meetings when they know it’s always going to be on, say, the second Tuesday of every odd-numbered month from 7:00 to 9:00 PM. Remember that weekends are also very busy for families, so whenever it is that you choose to hold your meetings, keep in mind that the key factor is to make it fixed frequency and reoccurring. Parents can program in the dates of the meetings into their calendars for an entire year in advance and plan ahead for childcare.

By being consistent like this, you have met the criteria needed for support. If you think about it, in order for something to be a support, it first must be stable, structured and reliable. To be universal, the support group should be open to all parents of children with permanent hearing loss, regardless of where they go for services or what region of the state they come from. Unlike in the clinic where the focus is on the child, the support group maintains focus on the parent and the parents’ needs.

This is not a playgroup. This is a parent group, and in order to offer universal parent support to accompany universal newborn hearing screening, it is important to avoid themes, such as something along the lines of communication choices. Specializing the group should be avoided, like creating groups specifically for parents of children with cochlear implants or parents of toddlers or parents of teens. That will only restrict the support. Themes and specializing the group are things which shift the focus away from addressing the basic parent needs, which are the social, educational and emotional needs. A parent support system, or as I like to call it, a universal emergency assistance plan, should not be exclusive in any way and should focus on all parents of children with hearing loss regardless of the degree or type of loss, regardless of the child’s age, regardless of whether the child uses hearing aids, cochlear implants, both, neither, and certainly regardless of how they choose to communicate.

In Massachusetts, we do have a wonderful, large cochlear implant gathering every other year. It’s almost like a convention, and that is a very specialized group that meets together for children and adults with cochlear implants. It’s a wonderful convention that does offer support. And I’m not saying that something like that should be avoided, but when we’re talking about adding a universal parent support group to accompany universal newborn hearing screening, I think those are two different things. Something like a cochlear implant biannual meeting is a wonderful resource that can be shared with parents, but it is not the same thing as a universal parent support group. The common factor is that they are all parents of children with permanent hearing loss, and their needs have been identified, at least in my case, as psychosocial, educational and emotional, and that’s where the focus must remain.

At the time of diagnosis, it’s common for the audiologist to hand the parents an appointment card for their child to take the next step, which is typically a hearing aid consultation or some kind of other follow-up appointment. In addition to the appointment for the child, the parents should also be given an appointment for them to attend the support group (Figure 5). This card will not only increase attendance to the support group, but it also acknowledges the parents’ needs right from the very beginning. It tells the parents, “We appreciate that you have needs. Here’s your 9-1-1 system.”

Figure 5. Example of appointment card to support group meeting.

This appointment card is just-in-time information. It is not an overwhelming informational packet. It is effective, and it’s certainly efficient. One easy way to motivate parents is to ask for RSVPs, as you can tell them it’s needed to properly plan for refreshments. Now, for some, just knowing that there are going to be refreshments is enough to get them to show up. For others, knowing that they are going to be relied upon to bring the refreshments allows for commitment to the meetings. Every year I pass around a voluntary refreshment signup sheet for the year, and I ask parents who wish to take turns bringing refreshments to the meetings. Nowadays, it’s easy and free to build very simple Web sites. This can be a great way for parents to find out about the face-to-face meetings as they are doing their online self-help searches, and once you have actually gathered a group of parents together, the first thing you should do is get their e-mail addresses. I collect e-mail information at the time of diagnosis or at the hearing aid consultation appointment.

I ask parents if they would like to be added to an e-mail contact list for parent support, and if they do, I can send out e-mails. I send them out via blind CC (carbon copy) to ensure privacy, but I remind parents about upcoming meetings and request the RSVPs. I also share local events and happenings, any relevant resource for parents of children with hearing loss in the area. This enhances attendance and encourages commitment to the support group meetings. Of course, in this global information age, it’s very easy to start up a Facebook page or a Google Group to supplement the face-to-face support group meetings. This is an easy way to keep connections going during the time between the in-person support group meetings. I’ve had a couple parents wish that we could have face-to-face meetings more often, but I could witness that they’re keeping in close contact and supporting each other through Facebook.

Every support group meeting should begin by establishing ground rules. This is a critical key that is needed to ensure privacy and comfort. It helps in the facilitating of the support group meetings. It is important to provide a written copy to all newcomers and review the ground rules at the very start of each meeting. Ground rules can be referred to later on, so if the facilitator of the group needs to, they can rely on the ground rules once they’re established. Whoever is running the group may, at times, be called upon to redirect conversations or regulate the meeting from being dominated by one or two strong personalities, which does happen. Ground rules can help with this, but they are also somewhat like the HIPAA of the support group. It reminds the attendees that the personal stories that are being shared at the meeting will remain confidential. Without this sense of privacy and structure, some participants may be reluctant to become involved, therefore leading to an ineffective system. To be effective, the support system needs to implement established ground rules.

Parent Needs in the Support Group

We’ve talked about the fact that parents wish to have their needs met in person in a group setting, and we’ve reviewed key factors needed to establish an effective face-to-face support group that meets on a regular basis. So, how do we address each of those three parent needs in the support group setting? Likely the easiest parent need to address is the psychosocial need.

Psychosocial Needs. Once you’ve arranged for the meeting to take place, you have basically accomplished this need. However, a few things are really helpful in establishing peer relationships. The first thing that I have noticed is that having people sit around a circle is very helpful. It helps people to see each others’ faces, and sometimes, if people feel reluctant or nervous, sitting around a table adds a sense of security.

The facilitator should start the introductions. Have the parents go around the room and introduce themselves with a brief description of their child or children with hearing loss. A simple, but very important detail is the nametag. This enables relationships to form. Without this simple step, people may leave the meeting without that really important connection, and the facilitator should promote the exchanging of contact information by passing around some sort of voluntary contact signup sheet along with something like three-by-five notecards or some form to make it easy for people to start exchanging contact information on the spot. The goal here is for the peer relationships to continue outside of the group setting. This is how parents find their peers.

Psychoeducational needs. Specific educational needs of parents are going to vary based on many factors, including currently-available local resources. I have practiced audiology in Ohio and Massachusetts, and I did my training in Pennsylvania. I can tell you that in those three states alone, I have seen very different resources that are available to parents. The educational needs of parents will vary over time with the development of the child and as the technology changes, as we have seen in the last 20 years. These needs will change based on different regions of the country or state and for different cultures as well. But finding out what parents need in regard to education, specifically timely information, can be accomplished by simply serving parents in your area.

At one meeting, you can regularly ask parents what information they need at that current time to help them raise their child with hearing loss, and then, as the facilitator, try to make arrangements to address the hottest topic at the next meeting or two if you can. This will provide parents with that just-in-time education that they need based on the current requests for information. This can very easily be accomplished by inviting a guest speaker to volunteer their time to come to the support group meeting. Some examples of invited guest speakers are speech-language pathologists, teachers of the deaf, literacy specialists, psychologists, or geneticists. One time I had a panel of successful young adults who grew up with hearing loss, and then a few months later I had a panel of the parents who successfully raised young adults with hearing loss.

Local resources might be available for you to draw from. For example, here in Massachusetts, we have the Mass Commission for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, so I’ve had people come from that group. I’ve had our Department of Public Health parent outreach specialist come. Audiologists can come to these meetings. Parents always are wondering how to interpret the various diagnostic testing that their child has to go through and how to better understand the results. The list can go on and on for guest speakers, but you really should not have any trouble finding speakers such as these who are willing to volunteer their time to speak, because it actually benefits the speaker and often fulfills a need that the speaker might have to spread the word around about their services. To the professional guest speaker, this is often free marketing, and when their information is delivered to a roomful of parents, it can spread like wildfire.

Psychoemotional need. Likely the most difficult parent need to address is the psychoemotional need. Many audiologists probably wish to outsource this one to social workers or psychologists or to even other parents of children with hearing loss in hope that if you just get the parents together, they’re going to form their own support group and deal with the psychoemotional needs on their own. However, I would like to argue that the audiologist is likely the best professional to address this parent need in the proper setting, that being outside of the clinic and in a support group setting. As many audiologists may be out of their comfort zone addressing this parent need, I would like to explore with you how we can address the psychoemotional need.

Technically, support groups are a form of group therapy, and likely the most noted expert on group psychotherapy is Dr. Irvin Yalom. Dr. Yalom has spent most of his professional life studying the clinical, social and psychological research surrounding the “power of the group,” as he calls it. He has authored several books, including Love’s Executioner (1989) and a very large book called The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005), which is where I gathered a lot of the information about his work. Changing the phrase “support group” to “group therapy” may sound daunting to the audiologist, but let’s look at that word “therapy.” What does it mean for something to be therapeutic?

Dr. Yalom points out that the result of therapy is not necessarily a cure, but rather a demonstrated change or growth within an individual (2005). What would that mean in regard to the parent of a child with hearing loss? Well, when looking at the parent needs that I discussed, it could mean that, number one, the parent finds their peers; number two, parents gain the education that they need; and number three, parents change or grow as a result of their strong emotional reaction to the fact that their child has hearing loss. Have you ever heard parents say something like, “Well, I’m stronger now because of this,” or, “My child has given me a whole new perspective or a whole new appreciation for life,” or, “Along with all the difficulties, my child has taught me so much, and I would never want to give that back.” So, if support groups are a form of therapy and therapy means change, then we need to explore exactly what the mechanism is for change to occur.

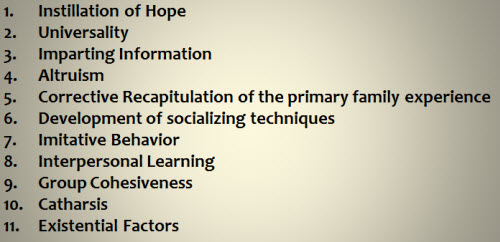

Dr. Yalom has identified these 11 factors (Figure 6), which are core mechanisms of change, in his opinion. He believes that these can very easily be achieved in the group setting, and these therapeutic factors are intrinsic to the therapeutic process. According to Yalom, once a group facilitator masters and understands how to modify these factors and incorporate them into specialized group therapy situations, that facilitator will then be in a position to fashion a group therapy that will be effective for any clinical population. So, this could be a cancer survivor support group. It could be a recently-lost-your-loved-one support group. I think these could also be applied to a support group for parents with children with hearing loss.

Figure 6. Dr. Yalom’s 11 therapeutic factors (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005).

Now, in closely studying these 11 factors, I have identified 7 which can actually be directly applied to this parent-support-group model. Yalom describes each factor in his book (2005). However, he notes that they are interdependent, and they really don’t occur separate from each other. Participants in the same group will benefit from widely different clusters of these therapeutic factors. Some people might get more benefit from a few of these factors, and others might be completely different factors at that time.

These are not impossible factors for a pediatric or a family practice audiologist to incorporate into the facilitation of a parent support group setting. In fact, I want to go through most of these briefly to show you just how simple it can be.

Instillation of hope. This is where the belief that the support group will help is enough to actually help. Testimonies of other parents who have found help and support from the group can inspire newer parents to have hope and get a sense that everything’s going to turn out okay. Just knowing that the support group exists in case they need it is enough for some parents to feel comforted.

Universality. When they first learn of their child’s hearing loss, parents do not know another parent of a child with hearing loss, and at that moment, they have no peers in regard to this new situation. They are alone. Universality is the realization that peers exist. This is where the group setting allows the parent to be validated and accepted by other parents and then gains a sense of being more in touch with the world because of it. The saying “We’re all in the same boat together,” is universality.

Imparting information. This is tied directly in with the psychoeducational aspect. It can be information learned from an outside source, like the guest speaker that we just talked about, but it can also be information learned from peers and group members or leaders of the group. Professionals can often clarify misconceptions that are being said in the group setting, so a professional facilitator can counsel about what to expect or treatment options and recommendations. Direct advice can also come from the members of the group. I witness parents helping each other out all the time. Parents learn from each other.

Altruism. Altruism is when members of the group gain through the act of giving. When a parent of an older child offers words of hope to a mother of a newly diagnosed baby, the parent of the older child has just experienced altruism. There is something intrinsic in the act of giving that is refreshing and boosts self-esteem. Group meetings offer a rare opportunity for altruism to easily take place. In fact, I often use the motivation of altruism when encouraging a parent to attend the support group for the very first time. I will often remind the parents that their help and advice could be very useful to some of the newer families that might be coming to the meeting. But, I do want to clarify that altruism does not occur when you pay the parent to help another parent. For instance, the parent outreach specialist who receives a paycheck from the Department of Public Health or some other source is gaining monetary benefit from their parent contact. Altruism is naturally occurring when the parent volunteers to help another parent.

Interpersonal learning. This is the learning that takes place through our relationships with others, which teaches us how to understand our own situation better. This is where parents learn the new language that they need in order to understand this developmental emergency that they’re suddenly faced with. You learn about yourself by hanging out with other people who are similar to you or in a similar situation as you, and, of course, this is accomplished easily in the group setting.

Group cohesiveness. Members of a cohesive group are accepting of one another, supportive of each other, and they’re inclined to form meaningful relationships. Group cohesiveness is a very significant factor in the success of support groups and the outcomes of the support groups. Without this factor, the peer relationships would not form. When facilitating a support group meeting, I always excuse myself and any other professionals that are in the room with me. We go to a different area so that the parents can really form the bonds that they need to form without the professional there. Often, at the end of a support group meeting after everybody leaves, I go to the parking lot to get in my car, and there’s this little parking lot after-party, as I call it. The support group members are literally stuck together like glue. They’re cohesive. That’s a perfect example of group cohesiveness.

Catharsis. Catharsis is getting things off your chest. Catharsis can take place in a parent support group setting by utilizing what I like to call talking points. This is where I have parents go around the room and each discuss a talking point. I’ll say something like, “Tell us all, how did you feel that moment that you first learned your child had hearing loss?” or, “Describe some of your greatest frustrations right now related to raising your child with hearing loss.”

And as we go around the room and each parent discusses, it brings out a lot of emotion. David Luterman is really great at this part. I’m very lucky living in Massachusetts. It’s been a pleasure to have Dr. Luterman as a guest speaker at two of the past meetings that I run. He always starts off the meeting by simply asking the parents, “What hurts?” Catharsis is expressing feelings and emotions and being able to say what’s bothering you instead of holding it in.

It is venting, basically, but catharsis alone is not enough to heal strong emotions or psychological pain. Catharsis is not sufficient on its own. However, catharsis will enhance that group cohesiveness. Emotional expression is directly linked with hope and interpersonal learning, so just keep in mind that while it’s important, catharsis is only part of the whole process, and it really must be complemented by these other factors. So, let’s see if this stuff really works.

Survey Questions Relating to Therapeutic Factors

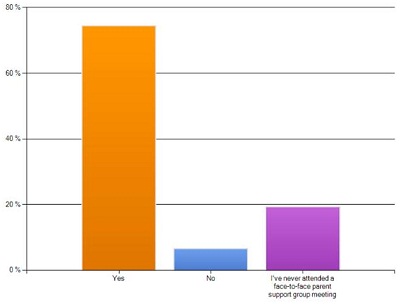

The survey question to address instillation of hope was, “Do you feel more hopeful about your child’s future since you have attended a support group that meets face to face on a regular basis?” About 20 percent of parents that took the survey had never attended a support group meeting, and that is this purple bar you see in Figure 7. So, just ignore that purple bar for this question, because these people never attended, but of those that had attended a support group meeting, 92 percent said that they do feel more hopeful.

Figure 7. Do you feel more hopeful about your child’s future since attending a support group?

Can you achieve imparting information in a support-group meeting setting? The question here was, “Have you gained information and education needed that helps you raise your child by attending a support group that meets face-to-face on a regular basis?” Of those who have attended a support group, 91 percent report that they have gained the information that they need to help raise their child with hearing loss.

Can we achieve altruism in a parent support group setting? The question was, “Do you believe that you have helped another parent of a child with hearing loss by attending a support group that meets face to face on a regular basis?” Of those who have attended the group, 90 percent feel that they have helped another parent.

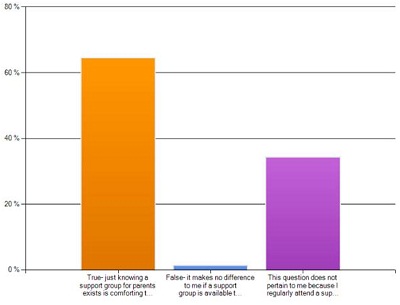

How about group cohesiveness? When asked, “Do you feel that you’re more connected with other parents since you have attended a support group meeting?” 85 percent reported that they felt more connected with another parent since attending the group. The next question was, “I have never attended a family support group meeting or I’ve only attended once or a few times, but I feel comforted knowing that there is a support group available to me if I ever needed it.” The bar in purple this time is to be disregarded, because those are the respondents of the survey who regularly attend parent support group meetings (Figure 8). So, of those that either never or rarely attend, 98 percent report that they feel comforted just knowing that the support group exists. Just knowing that there are parents out there in case they ever needed them touches upon universality.

Figure 8. I feel comforted knowing that there is a support group available if I ever needed it.

This question also addresses the fact that there is a natural ebb and flow to the attendance with the open-ended meetings that continue on a regular basis. It seems like there’s always a steady attendance rate, but parents will come and go to the support group meeting when they need support, and when they experience change or growth, they may fall out. That’s all part of that therapeutic process that we discussed earlier. They may not necessarily return or at least attend regularly, and that’s okay. The goal is for parents to experience that change or growth and then move on with their lives. Some may need the support just in the very beginning of that developmental emergency, but for others, they may continue to need support throughout their entire child’s life until they become young adults or teens.

Some parents return at different times to get different types of support. For example, at age three, when the child is transitioning out of the early intervention programs and into a public school system, that might be a time when parents need advocacy from their peers. They need that support. How do I go about getting this information that I need to transition my child to the school system? I’ve also had parents of teenagers come during those very challenging teenage times where they don’t want to wear their hearing aids anymore, so they can pop up at any time.

Who Facilitates the Support Group?

Before we move on, we need to discuss a very critical factor in all of this, which is the role of the group facilitator. We have identified the needs of parents, how to best address those needs and key factors, all the key factors that make a support group successful and effective. But, who should drive this process of parent support? Traditionally, there are two types of support-group facilitators. Support groups can either be peer led or professionally led. It’s my opinion that the same professionals who are responsible for identifying the developmental emergency are the same professionals who should be providing the emergency assistance plan.

First, let’s look at some general pros and cons of peer-led versus professionally-led support groups. The main benefit to peer-led groups is that there’s a genuine form of empathy as the group leader is actually a member of the group as well. However, in the case of the parent peer-driven group, there is something very critical, which is that the child who brought them to this place to begin with grows up. One of the defining features of support is stability, and I was actually inspired to start a professionally-driven parent support group as a result of the fact that there was a parent-led group that existed many years ago in the area where I practice, which dissolved as a direct result of the children growing up and becoming adults and the parents no longer needing to meet on a regular basis. However, as we all know, there are always new parents, so parent peer groups also can run the risk of becoming exclusive where cliques can sometimes form. Without having a neutral moderator, sometimes strong personalities can take over in the peer-led setting.

There may also be a lack of uniformity amongst the parent peer-driven model, and it is not uncommon for peer groups to have trouble staying focused on the general needs of parents, especially when you introduce a hot topic, such as mode of communication type or oral communication only versus sign language or total communication. These are topics that shift the focus away from parent support and on to opinionated debates, which can actually have the opposite effect of group cohesiveness, resulting in a divide and a very ineffective support system. But, with professionally led groups, there is sustainability.

The role of the professional is static. It is not going to change much, and you will have more uniformity. The professional can remain neutral and ensure universality. The professional can act as a filter when hot topics are being discussed. The professional facilitator can keep conversations moving or redirect conversations when it is observed that there is a need to do so. If the audiologist is willing to give back to his or her profession through volunteerism and is willing to facilitate a professionally-led parent support group on an occasional, but regular, basis this would require a small commitment, perhaps a few hours outside of the clinic each year.

A survey question from an older survey reads, “Some parents are highly motivated to facilitate and run support groups for parents of children with hearing loss, whereas other parents are not interested in being in charge of running the support group and would rather attend a support group that is already established. Which would you prefer?” Seventy-seven percent of the parents preferred that support groups are facilitated by professionals, and although there are very popular peer support groups that do exist, like Alcoholics Anonymous, the result that I found on this survey is consistent with other research. If you look into the research of this, most support group attendees actually prefer professionally-led support groups over peer-led support groups.

Hear My Dreams

I would like to talk briefly about Hear My Dreams, which is a professionally-led support group for parents of children with hearing loss that I founded in 2007. Over 95 families have attended Hear My Dreams, and the attendance consistently ranges from about 12 to 24 parents for each meeting. Hear My Dreams meets every other month, and I volunteer my time to organize and facilitate the six meetings per year. I run the group not as a non-profit organization, but rather through pro bono and volunteer efforts. I have only paid for a few things out of pocket to keep it going. For example, it costs about $20.00 a year for the Web site domain name and about $10.00 a year for the business cards. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health Federation for Special Needs has reimbursed a parent for the pavilion for our annual meet-and-greet picnic. So, in addition to the evening parent meetings six times a year, one Saturday afternoon each summer, we all gather together for a potluck picnic with everyone, including children, friends, professionals and extended family.

This is where parents witness that the hearing loss does not define the child. This, to me, is the real measure of successful outcomes. There is clearly a need for this type of smart family support system as demonstrated by the fact that parents have traveled over 50 miles over an hour in every direction to attend a Hear My Dreams meeting. That tells me that this type of support is definitely worth it if they’re willing to drive that far. This advertisement-free, self-made Web site has approximately 100 to 200 hits per day from all over the world.

I know for a fact that some parents have found out about Hear My Dreams by stumbling across the Web site when they’re searching the Internet for help. As supporters of the universal newborn hearing screening process, we must all be held accountable to promote the most successful outcomes that we can. Family support was supposed to be part of the universal newborn hearing screening process. Therefore, audiologists, and specifically pediatric audiologists, it is time that we organize and create protocols to develop family support systems to accompany the universal newborn hearing screening process. Each diagnostic center should offer regularly scheduled, in-person support groups that meet consistently a few times a year.

Let’s not outsource this important part of the universal newborn hearing screening process. Let’s develop an effective universal parent support group, or a UPSG, to accompany universal newborn hearing screening, and let’s improve upon this wonderful tool that we have to promote successful outcomes.

That is actually all I have for you today. I know we don’t have a lot of time for questions. Maybe I answered them, because they’re gone now, but if anybody does have any questions or comments, feel free to e-mail me at the address you see here, hearsmartaud@gmail.com.

Questions and Answers

Are parents who attend support group meetings more compliant with their audiologic management plan?

I would have to say so, but I haven’t actually done any research on that. That would be a great little research project. Subjectively, I can say that that seems to be the case.

How do you determine the frequency of meetings? Are more frequent meetings resulting in less attendees, and less frequent resulting in greater attendance?

That’s a very good question, because when I first surveyed the parents, parents didn’t want to come every week – they’re busy. They didn’t want to come every month. I actually asked that question. I said, “How often do you want to meet?” and the majority of parents in my area said they wanted to meet every other month. I think it’s going to change depending on where you are. I would just get as many parents as you can get together for the first time and ask them these questions. I think it’s going to vary.

What is an appropriate distance that we can expect people to travel? I live in Idaho, and there are a lot of rural areas. It is challenging to bring people together when they live in rural areas.

I know, that is a challenge, and even here in Massachusetts I have people that will send me an e-mail saying that they don’t have transportation to travel that far, and that’s why I’m doing this talk.

I’m trying to encourage more audiologists to volunteer and try to make this something that is more common. It’s really important to have these meetings at an accessible location. I’m holding this meeting now in the town where I live. I find it easier for me to volunteer my time that way, but I think that that’s a challenge that we’re all going to have to face.

Do you recommend having an agenda with a specific topic to be addressed at each meeting, or is it more effective to provide a more open-ended format?

This is a good question. I used to always hand out an agenda, and it was very formal, and it was good. It kept us on track, but it seems that lately I haven’t done that, and it’s been working just fine. I know that different facilitators of support groups that I’ve spoken with have very strong opinions about having an agenda. I don’t think it really matters that much. One thing that I like to have on an agenda is a biography of the guest speaker. It’s easy for me to introduce the guest speaker if I have something in writing, and parents can take that home. So, I think it’s fine either way. It might depend on who your guest speaker is whether or not you have an agenda. I know when Dr. David Luterman came to be my guest speaker, he didn’t want to have anything to do with an agenda. He just wanted to get right into it.

Would you also include deaf families who participate in Deaf culture in a universal parent support group?

Absolutely. One of the parents that comes to the meetings every now and then has come with an interpreter. I was able to actually get the Department of Public Health here in Massachusetts to kindly reimburse the interpreter for her time, and that was wonderful for the other parents to have. I do have people that come and go. Like I said, there’s that ebb and flow, but it’s universal. It’s not just a support group for those 98 percent. The two percent parents that have hearing loss are also welcome to this group, and I think the other parents learn from them very much also.

Is it important to have the same professional as the facilitator, or could this be a team effort?

I think a team effort would be a great idea, because if you have a team of six people and you have six meetings a year, then you’re only responsible for facilitating one meeting a year. I think the point that I was trying to make is that professionally-led support groups are important and are different than parent-led or peer-led support groups. I think that splitting it up between audiologists would be a great way to do it.

References

Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. (1991). 1990 position statement. American Academy of Pediatrics News, 7(4), 6-14.

Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. (1995). 1994 position statement. Pediatrics, 95(1), 152-156.

National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders. (2013). Quick statistics. Bethesda, MD: Author. Retrieved from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/Pages/quick.aspx

Shulman, S. Besculides, M., Saltzman, A., Ireys, H., White, K. R., & Forsman, I. (2010). Evaluation of the universal hearing screening and intervention program. Pediatrics, 126, S19-S27.

Yalom, I. D. (1989). Love’s Executioner: & other tales of psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Yalom, I. D., & Leszcz, M. (2005). The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Cite this content as:

Ford, M. (2013, March). Pediatric hearing loss: providing effective parent support. AudiologyOnline, Article #11668. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com/