Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: What You Need to Know, presented by Susan Holmes-Walker, PhD, RN.

Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Verbalize the relationship between opioid misuse and acute hearing loss.

- Apply principles of quality pain management.

- Apply principles of prevention in the context of the transition from acute to chronic pain.

Introduction

This course is intended to improve the understanding of audiology professionals on the relationship between the opioid epidemic and pain management. A brief review of literature discussing the relationship between hearing loss and opioid misuse will guide the discussion. David Thatcher, former Surgeon General of the United States, shared that 80% of what influences your life expectancy happens outside of the healthcare system. This is disconcerting that we, as providers, only have a 20% influence on their life expectancy. It's very important for us when we're dealing with patients, whether they're having pain issues or hearing issues, to understand that what we're doing is just a tiny part of what actually is impacting their life. We also need to understand that our patients deal with multiple issues. The opioid epidemic is multifaceted, as I can probably assume that certain types of hearing loss have multiple causes. It's very important for us to realize that we play a small but important part in influencing our patients' life expectancy. They have a huge burden outside of healthcare that definitely dictates their life expectancy.

Literature Review

I wanted to do a short review on opioid misuse and hearing loss to give you a context to keep in mind as we go through the presentation. A few references that I wanted to briefly review with you.

- It is likely that opiate-associated hearing loss results from the interaction of ingested opioids with opioid receptors within the inner ear (Nguyen, 2014)

- Presence of opioids in ‘diet’ pills, including methadone and heroin, have been implicated in acute hearing loss (MacDonald, 2015)

- Temporary hearing loss may occur after inhalation of oxymorphone (MacDonald, 2015)

- Opiate abuse can cause temporary or permanent hearing loss. It is possible that after several episodes of temporary, unreported hearing loss, the loss may become permanent (Rawool, 2016)

- Patients with fibromyalgia (chronic pain condition) had an increased likelihood to report subjective hearing loss (Stranden, 2016)

- Hearing loss is independently associated with prescription opioid use disorders among those aged 49 years and younger (McKee, 2019)

- Babies born addicted to opioids may have neurological problems, including failed hearing screenings (Williams, 2018)

- There is a need for audiology professionals committed to working with high-risk mothers and their children (Williams, 2018)

- Limited studies are available exploring the link between opioid misuse and hearing loss… possible thesis or dissertation topic (Campbell, 2018)

Research Summary

One thing to think about is that babies born addicted to opioids may have neurological problems, including failed hearing screenings. Unfortunately, there are mothers that have addiction issues and may misuse opioids during pregnancy. It is important if you're working in an acute care setting where you're caring for newborns and performing hearing tests or involved in that process, it's important to think of the possibility that this newborn's mother may have ingested opioids, which may have been the cause for that child to fail a hearing screening.

The second point I wanted to bring up is there is a need for audiology professionals committed to working with high-risk mothers and their children. We know that it takes a special person to work with high-risk mothers, whether they're high risk because of their own personal decisions, because of socioeconomic status, because of multiple psychosocial issues that can and often cannot be prevented. It's important that we have compassionate individuals who are willing to work with these populations and with their children who are unfortunately subjected to the poor decisions that oftentimes mothers make.

The third point I wanted to make was that there are very limited studies available exploring the link between opioid misuse and hearing loss. I wanted to encourage anyone who's online who has a research project or is thinking about moving into a research career. There is room for research done specifically by audiology professionals that can explore the link between opioid misuse and possibly come up with some interventions and ways to address opioid misuse in the context of hearing loss.

You could not turn on the television, read a newspaper or go to any media outlet and not hear something about the elephant in the room, which is opioid misuse. You see information about lawsuits. You see more information being shared about unintended overdoses. Every state in the country has been now required to come up with a plan to address the opioid epidemic. We're talking about it, but the important thing and a very important reason why you're here today, in my opinion, is to get information so you can better understand how you as a hearing professional can better understand the opioid epidemic, possibly obtain some tools to help you care for patients who may be struggling with opiate misuse and just have some general information that you can embed into your practice.

Case Study: Patient Introduction

I wanted to introduce a case study, and we'll refer to this periodically throughout the presentation. This is a 35-year-old female. She presents to the emergency primary, reporting acute hearing loss. She has a prior medical history of a Cesarean section about two months prior. She has some chronic back pain due to a work-related injury. As far as her social history, she is a single mother who has been unemployed since her delivery, and she has a history of alcohol misuse prior to pregnancy.

The Current State of the Opioid Crisis: How did We Get Here?

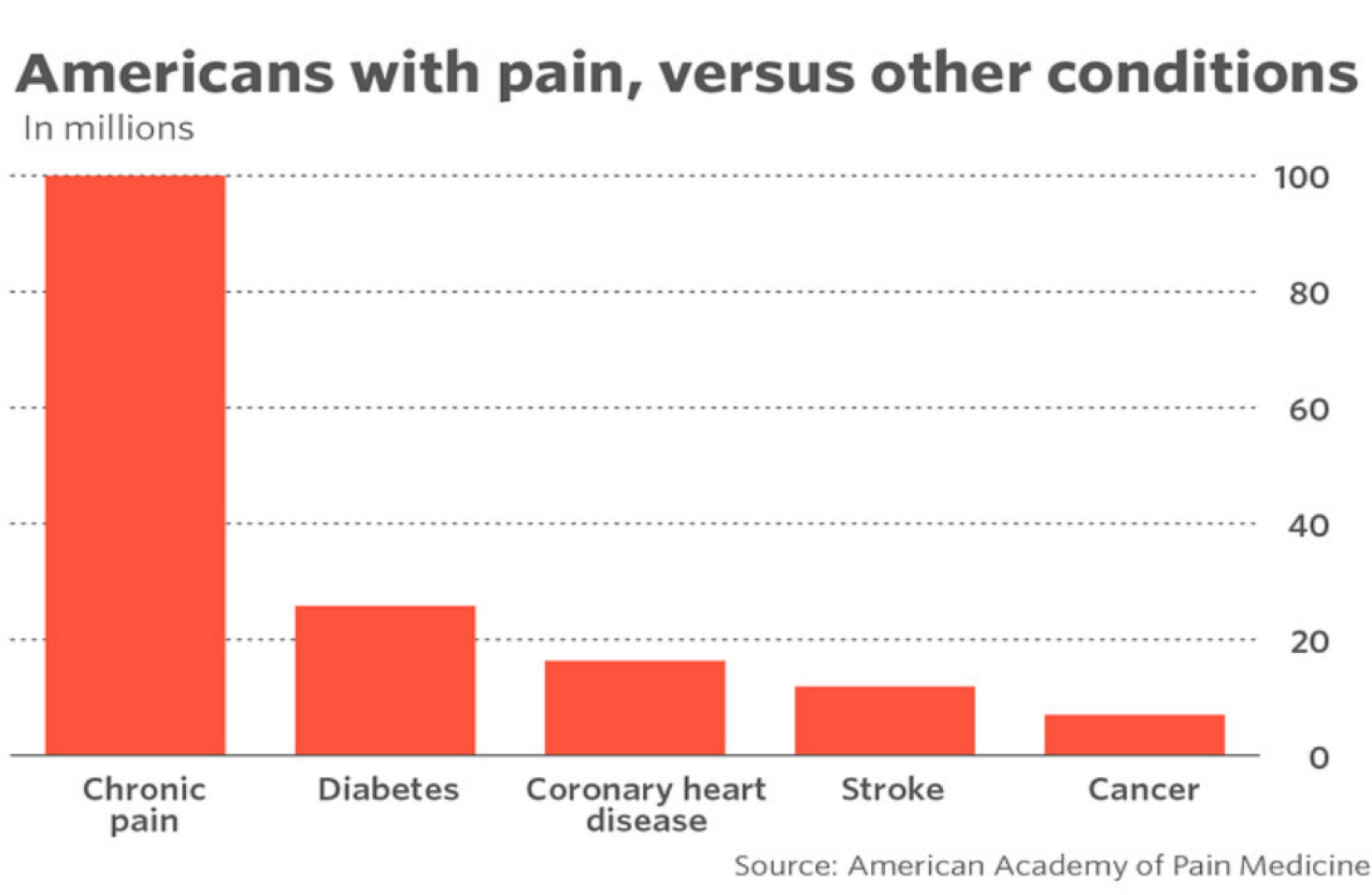

Figure 1 depicts Americans with pain versus other conditions. You will see that these are fairly commonly occurring conditions, the four to the right of the graph, cancer, stroke, coronary heart disease, and diabetes. You will note that chronic pain very significantly outnumbers patients who are living with these other conditions. As a matter of fact, if you totaled all four of those categories together, you would still not see the total in relation to patients suffering from chronic pain. One thing to consider is that each of these patients in these other categories may possibly feed into this group of chronic pain patients. You may come across patients, family members, people you associate with who actually have chronic pain in the context of cancer, stroke, coronary heart disease, or diabetes. Unfortunately, some of the treatments for these other diseases can cause chronic pain and other conditions, which will definitely increase the total number of patients living with chronic pain in addition to suffering from other comorbidities.

Figure 1. Patients in the other listed conditions may contribute to the number of those living with chronic pain.

Case Study: Likelihood of Opioid Use

Getting back to the case study, when you think about this patient, and we talked about she's a 35-year-old female, she had a recent C-section. She probably has some social stressors. She has a history of chronic back pain. What are the chances this patient is taking some kind of opioid? It's the hope that she is taking something appropriately prescribed by a nurse practitioner, physician assistant, medical professional. Oftentimes, we find that patients are able to access medication that hasn't been specifically prescribed to them, which becomes a challenge and can feed into the issues related to the opioid epidemic that we're facing today.

Pain Management Facts

The national economic cost is about $560 to $635 billion per year. We've learned that pain is unique to the individual and subjective experience. We've also learned over time that pain is influenced by a variety of biological, psychological, and social factors. We will get into some of those things later in the presentation. For many patients, the treatment of pain isn't adequate. One of the reasons pain treatment can be inadequate is because of limited access and availability to effective treatments. It could be because of where the patient lives. This could be because of poor insurance resources. I have a friend who had an acoustic neuroma, and she required a hearing aid. When she shared with me how expensive these devices are and the fact that her health insurance plan was not going to cover very much of this required or much-needed device to improve her hearing, I could empathize with her and her frustration. Many patients with pain issues may not have insurance plans that cover necessary treatments, which can be frustrating for the patient and anyone trying to provide a reasonable treatment plan for that patient.

A second reason why treatment of pain is inadequate is that there is inadequate clinician knowledge about the best ways to manage pain. I've seen recently within the last couple of years where there are now mandates in medical schools to teach students about how to properly manage pain. You would think that given the medical profession has been established for centuries, that that would have been mandated previously. That was a little surprising to me. But I do know as I've been trained as a nurse and have taken some pharmacology classes, assessment classes, and other things throughout my education and career, nurses do get a significant amount of education on pain management. You may or may not know that patients are in the hospital pretty much for nursing and other types of care, not necessarily medical care. We know that our physicians are extremely important. They guide the treatment plan. It is the people working at the bedside, whether it's physical therapy, audiology professionals, nurses, whoever is coming throughout the day to care for those patients are the ones that are really very important as far as care of patients when they're in acute care settings.

Opioid Prescribing After Procedures

This will help us have a better grasp of the real issue at hand when we're talking about the opioid epidemic. There was a research study performed where they looked at opioid prescribing (Howard, 2017). What they found was that patients were prescribed from 12 to 120 hydrocodone tablets after general surgery procedures. You look at that number and say, wow, that's a huge range of pills prescribed to someone after a general surgery procedure. When they delved further into this data, they found that 77% of the prescriptions were written for 30 to 160 tablets. When they took a deeper dive into the data, they found that the range of actual pills taken was approximately zero to 30. You would think that there are patients who were prescribed 120 pills who took zero pills or who took 30 pills. The entire prescription is still available if these are these patients who did not take any of those pain medications that were prescribed to them.

The Problem

The problem is the patients were over-prescribed opioid medications after surgical procedures. This leads to having too many extra opioids in the community. I have friends who are in real estate, and they have said that it has become so bad that when they have open houses with their clients who are trying to sell their homes, they have been instructed to remove any opioids or other prescriptions out of their medicine cabinets before they hold open houses. Because there are individuals in our communities who actually go to open houses and go through medicine cabinets looking for opioids and other medications with ill intent. That's something to keep in mind as well if you're selling your own home and you have prescription medications, you may want to make sure you remove those as well. Another part of the problem is that prescribers need more education on how to assess and appropriately prescribe medications to treat surgical pain. Again, that gets to the lack of training and education for some physicians in learning and teaching them how to appropriately prescribe and manage pain.

Keep in mind that medications do expire and probably should be disposed of and not kept around, especially if you have teenagers or children. In other presentations I've given, I've traveled to different states and looked specifically at opioid misuse trends. There was a sad story that I found in Indiana where there were two brothers who were hockey players who went to a party at their friend's house. Their parents went into their room the next morning to wake them up, and both of their teenage sons had died from an opioid overdose. They had gone to a party the night before. Their friends had access to opioids, and unfortunately, these young men took the opioids and unfortunately passed. That was a tragic death that could have been prevented if those extra opioids weren't around and accessible to the teenagers who attended this party.

2016 CDC Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids

In 2016, the CDC came up with new guidelines for prescribing opioids. These guidelines were pretty much the foundation of most of the states' plans to address the opioid epidemic. No matter what state you live in, you probably have seen some new legislation that's gone out and new guidelines for opioid prescribing, access to medications. These were based on these CDC guidelines. There have been some requests for updates to these guidelines as things have changed over the past three to four years. There may be something coming out soon, but these are the guidelines that states are currently using to come up with interventions and plans to address the opioid epidemic in their communities. I just wanted to highlight a few of these guidelines for prescribing opioids.

Alternative Treatments

The first is that the CDC is encouraging and stating that opioids are not first-line therapy. It is important that patients are offered other alternative treatments besides medications when they have a pain situation. They have suggested that if opioids are used, they should be combined with non-pharmacologic therapy and non-opioid pharmacologic therapy as appropriate.

Individual Experience

Pain is a unique and individual experience. Just because one patient can tolerate, X doesn't mean that a different patient with a similar presentation can tolerate the same thing. This is all very important to make sure that pain treatment is individualized for that specific patient in question.

Pain at Rest / Pain with Movement

Also, the CDC guidelines propose that we should establish goals for pain and function. We want to make sure that there are appropriate goals for our patients who are experiencing pain. I used to work with a team of anesthesiologists in the hospital, and we used to round and see post-surgical patients. We would go in and ask them, "How's your pain today?" They would give us a number. We would leave the room. Half an hour later, a nurse or someone else would call from the unit saying this patient is in pain. We would come back, we said, "You told us you weren't in any pain." Well, the patient's most common response would be, well, I wasn't in pain until I had to cough or move.

We had to modify our assessment plan to ask patients, "How is your pain at rest?" And "How is your pain at movement?" which helped us to identify ways to properly manage pain for patients who did need to have some type of activity to improve their recuperation.

Lowest Effective Dose

The next point I wanted to emphasize was the importance of using the lowest effective dose. I took some advanced pharmacology courses, and this principle is similar to that when starting patients on hypertensive medications. There's a saying that says, "Start low and go slow." So it's very important that you don't start a patient off with three or four tablets every four hours to manage their pain. You probably want to start with one tablet with a short time range, and then after you properly assess the patient over time, you may need to increase the dose. But it's very important to start with the lowest effective dose and then allow the prescription to have somewhere to go and not peak too high with the doses that are being prescribed. Another recommendation was to prescribe short durations for acute pain. Here in Michigan, where I currently live, there are two steps to this prescribing shorter durations. For patients who have had surgery, the intent of the legislation is that patients do not receive more than seven days of prescription pain medication after a surgical procedure. If patients are getting three days or less, they do not have the same criteria as far as education and accessing online prescribing systems to patients who receive shorter durations of medication.

Benefit vs. Harm

A few other key points from those CDC guidelines are that we need to evaluate benefits and harms frequently. You may have seen in the media or on the news about states suing pharmaceutical companies because they are accusing them of not properly educating prescribers and patients of the harms as well as the benefits of opioid therapy. That is a challenge that patients; they felt patients were not being appropriately educated on the importance of monitoring side effects and only using opioids when necessary. Again, in the state of Michigan, they have required patients who get seven days' worth of medication to also have a documented educational plan that is given to the patient along with that prescription.

Prescription Drug Monitoring Program

The CDC also required that prescribers review prescription drug monitoring program data. Most states, not all, now have an online prescription drug monitoring program, where if a patient comes in and has an acute pain issue and needs pain medication, you can enter that patient's name and information and find out where that particular patient is getting prescriptions. If they were doctor shopping when the last time was that they filled a prescription, and determine if they should need another refill, et cetera. In our state of Michigan, they have seen a three or four hundredfold increase in people who are registered to use the system and actually use it to determine if these patients have been getting opioids appropriately or misusing them.

Benzodiazepines

The last point from the 2016 CDC prescribing guidelines is that to avoid concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine prescribing. Benzodiazepines are usually prescribed for patients who have anxiety or other issues, and that can be a deadly combination when you're taking opioids and benzodiazepines because of the interactions of those medications.

Acknowledging Bias

All of us have stereotypes about patients—good, bad, or otherwise. One would assume that someone who just fell off of a bike would have more pain than a patient who was outside of a hospital with an IV pole, smoking a cigarette. I remember when I was a new nurse back in the '80s and early '90s, the biggest motivation to get a patient up out of bed was for them to go outside to smoke. We would disconnect their pain pumps or sometimes disconnect their IVs. They would go out to have a cigarette and come back. Of course, they would be in pain and need medication. We struggle with the fact that, well, if you could just disconnect it and walk that far to smoke, then you're probably not having pain. Well, pain is what our patients tell us it is. It is a unique experience, and we just have to be careful not to make any stereotypes and assumptions about patients and their reporting pain and how we should properly treat it. You would assume that the patient with the bike injury would be the patient that had more pain. If this patient who is outside smoking is using that as a coping mechanism and has some poorly managed and previously untreated chronic pain, he may have just as much or more pain as someone with an acute injury from a bike accident.

Core Principles of Pain Management

There are several important pieces to the puzzle that is pain management. The first step would be a quality assessment of pain. Next would be acceptance of pain when it's reported. The third step would be to take action when our patients are assessed positive for pain and when we have accepted that our patients actually do have pain. Pasero and McCaffery (2011) are two nurse pain researchers who have done a lot of work over the years researching pain and how to manage it.

Assessment

- W-Words

- I-Intensity

- L-Location

- D-Duration

- A-Alleviating/Aggravating Factors

When we think about pain assessment, this is an acronym that I've seen used where you use it when you're assessing a patient's pain. The W stands for words. What words are your patients using to describe the pain? I stands for intensity. What level are they rating the pain? You've probably all heard of the pain scale. What is your pain on a scale from zero to 10 when zero is none, and 10 is horrible? That's an example of intensity. We always want to make sure we know the location or locations of pain. When we think about our case study patient, she had some chronic back pain along with some potentially incisional pain from her C-section. She probably has pain in multiple locations. We also want to make sure we know the duration of pain. Is it a short-term pain? Is it long-term pain? We also want to engage our patients in conversations about alleviating or aggregating factors. What have you done in the past that's made your pain better? And what has made your pain worse.

Factors that Influence Pain Perception

Some factors that are noted to influence pain perception, how one interprets pain messages and tolerates pain, can be affected by your age, gender, culture, family and social support, emotional and psychological state, and memories of past painful experiences. I had a colleague when I was working on my doctorate who was a, is a nurse-midwife. They have done a lot of research on women who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. When they start having labor pains, unfortunately, they often have flashbacks to a past painful experience, and their labor pain can be very challenging to manage. Some patients may have issues that they haven't disclosed to you. It is possible that some post-traumatic stress issues in the past can trigger past experiences when dealing with a new pain issue. As far as pain assessment and best evidence, we must use the best words for screening. We're shifting towards asking patients if they're having discomfort versus pain.

Words Matter

Again, we've had to learn to modify our assessment questions and screening to ensure we're getting to the issue that our patients are verbalizing to us. We also know that we need to know the words that describe the pain. A little bit later, we'll get into different types of pain. There are categories of emotional, neuropathic, and nociceptive pain. As I said, I didn't want to get too technical, but we'll discuss that a little bit later. Then we also need to be sensitive to cultural and gender differences. When you approach patients from different backgrounds other than yours, we don't want to feed into stereotypes, but we want to be sensitive and empathetic with our care and make sure not to offend anyone who may have a different response to pain and different requests to guide their pain treatment.

Medication Side Effects

Now we will discuss opioid receptors. We want to make sure that we're assessing medication side effects and if the medication is actually helping a patient's pain. We know that there are four types of opioid receptors, they're mu, kappa, delta, and nociceptin receptors.

Mu receptors are located throughout the body, and opioid medication binds to these receptors, which is how pain relief comes about. Side effects from medications are based on where mu receptors are located and their function in the body. When we look at mu receptor location and possible side effects, there are mu receptors in our respiratory system.

If you are taking opioids and taking a fair amount, you may have a decreased respiratory rate, which means your dose may need to be adjusted. This is particularly speaking in the acute care setting after a procedure. In the GI system, we also have mu receptors. These mu receptors, they're also triggered by opioids, can cause nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Anyone who has taken opioid medication may have had one of these things or all three. That is why, because mu receptors that bind to the opioids also are in all of these other body systems causing these particular side effects. In the cardiovascular system, mu receptors are present. Once opioids are present and touch those mu receptors, you will have a slower heart rate. The central nervous system, you may notice that you or someone you've been around has reported some dizziness or possibly euphoria. That is again because of mu receptors in the central nervous system. There are also mu receptors in the central and peripheral auditory system, leading to sensorineural hearing loss. Those mu receptors again are triggered with that opioid medication, but can also cause these potential side effects, including sensorineural hearing loss.

Case Study: Asking the Best Questions

What assessment questions should we ask our patient about her overall health and pain history? This is just a general question. If you think of something to respond to, keep that in mind. You want to make sure you understand if she has any other health issues. You want to make sure you understand if she has any social issues that may impact her pain history. There are multiple things, and I don't think there's a wrong answer to this question.

Acceptance

The second principle of quality pain management is acceptance. Again, we as clinicians must accept the patient's report of pain. We know the self-report is the gold standard. We also need to have tools available so that patients who have dementia, who cannot verbally speak, patients who are not native English speakers also have a way to report their pain. Each hospital, another joint commission recommendation or standard is that you must have assessment tools available for each particular patient population that you're going to be assessing pain. There are specific scales for babies for patients with dementia that can be used and research and evidence based. We need to rely less on vital sign assessment and more on observing behaviors. We used to think that if your blood pressure was up, you were in pain. Some patients have low blood pressure or some hypotension when they have pain. It is very important to lay your eyes on that patient who's experiencing pain and be able to assess them and treat them properly. Sometimes we have to ask ourselves, just when we looked at the picture of the gentleman who fell off the bike versus the gentleman who was standing up smoking with his IV pole, that why is it so difficult for me to believe that this person is in pain? We have to accept what our patients tell us and work with them to come up with a good treatment plan. As far as action, once we assess the pain and once we accept it, our primary goal should be to prevent transition to persistent, which is another word we use for chronic pain. If persistent pain exists, we need to assess it separately from the acute pain issue. We want to make sure we're reviewing pain-related orders and documentation. We want to make sure that we're trying pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions. And we always want to remember that safety is first. We don't want to overmedicate patients, and then they have horrible side effects that they cannot recuperate from and possibly have challenges managing.

Acute, chronic, or acute on chronic pain?

I just wanted to briefly go over some definitions of those different types of pain. Acute pain is generally considered to be a symptom. It's a signal of a disease process that's associated with tissue trauma. For example, the gentleman who was on the ground after falling off the bike probably has some tissue trauma, and his cause of it obvious, based on the way he was laying on the ground.

Acute pain usually lasts less than six months. Some examples of acute pain would be someone who's experienced a tooth extraction that did not have nerve damage or possible complications, someone who had an uncomplicated appendectomy, or even someone who's had a hip replacement. You would expect within about six months, give or take. We also know that each patient may respond and recuperate differently. Within six months you should be back to "normal" and not having any ongoing pain issues.

When we also think about chronic or persistent pain, it is a diagnosis. Oftentimes our patients with chronic pain have to learn to live with their illness just like if they had diabetes or hypertension. For some patients with hearing loss you teach them strategies to cope, but you know that potentially some of the hearing loss that you treat and manage may not go away. So it's important to teach patients coping mechanisms and how to live with these diseases that are going to be long-term, chronic diagnoses. Chronic pain has also been stated to have no useful function. Someone can report back pain, and after multiple MRIs, x-rays, CT scans, there's no source found. That doesn't mean there isn't pain, but it's oftentimes challenging to treat, and patients get frustrated because they're told, "We can't find a reason for the pain," and actually they do still continue to have pain. Chronic or persistent pain usually lasts greater than six months. 100 million plus Americans are currently living with chronic pain and we need to be very sensitive to the needs of those patients.

There's a category called acute on chronic pain. I worked with Dr. Paul Hilliard in Ann Arbor at the University of Michigan Hospital. He basically said that acute on chronic pain is exactly what it sounds like. Often times opioid and anti-inflammatory medications work well for acute pain as a short-term solution. You may need to use some ibuprofen in addition to oxycodone to manage some acute pain and then hopefully get the patient back on their chronic pain regimen once that acute pain has been rectified. It's very challenging to treat acute pain per Dr. Hilliard, when a patient is already on opioids. I'm not spending a lot of time today on tolerance and those types of issues, but it's understandable that a patient who has been experiencing chronic pain for a long period of time and taking a lot of medication may require higher doses to manage.

Case Study Pain Classification

What kind of pain is she experiencing? I would think that she is probably experiencing acute chronic pain. She has a Cesarean section incision. She has some chronic pain. So she has some acute pain from that C-section and then some chronic pain that can be attributed to a previous back injury.

I wanted to pose this question to the group. Are you or someone you know living with chronic pain? If you or someone close to you is experiencing and living with chronic pain, you understand the challenges and the importance of being empathetic and having a good set of communication skills when communicating with patients who are struggling and trying to manage and cope with chronic pain as best as they can. When we think about categories of pain, there are three categories generally that we talk about. Nociceptive pain is a specific type of injury pain from a That's pain from an injury, disease, or inflammation, a sprain or a strain, from surgery or even trauma.

Case Study: Classification

When you think about our case study patient, the fact that she has a surgical incision from a C-section. That would definitely mean she falls into the category of having nociceptive pain. There's also neuropathic pain that results in damage to the brain, spinal cord, or peripheral nerves. There are patients who have had strokes who have nerve pain. You may be familiar with patients who are diabetics who have neuropathy or sensitivity in their extremities or their fingertips. There are patients who have a peripheral vascular disease that may have some vascular constriction, which can cause some pain, and also you can find, or patients who have had severe burn injuries may have some neuropathic pain because of damage to those nerves being burned. Also, we have emotional pain. It's an unpleasant feeling or suffering of a psychological, non-physical origin. I brought that up because when we talk to patients, and they explain or use words to describe their pain, the words that they use may help us identify which category their pain falls into. If someone's having emotional distress and they may describe their pain as nagging or unbearable. If someone's having neuropathic or nerve pain, it may be described as tingling or stabbing. If someone's having nociceptive pain, probably from an incision or a sprain, or a strain, they may describe that pain as being tender or sharp, or dull.

One important thing to take away is that usually, emotional pain and neuropathic pain are not responsive to opioids. If you have a patient describing their pain as neuropathic, an opioid may not be the best choice to manage that patient's pain. If a patient is having post-surgical pain, they may indeed be having nociceptive pain, and an opioid may be a good choice for that particular patient. We'll also ease over this question, but our patient who has the C-section incision, chronic pain, some social issues probably has pain in all those different categories. The emotional category, potentially the neuropathic category, especially if she has some back pain and may have some shooting pain down her lower extremities based on that injury. Then with that healing C-section, she indeed may also have some nociceptive pain as well. I think this can apply to preventing hearing loss and issues with hearing challenges as well as when we're thinking about trying to prevent acute pain from transitioning into chronic or long-term pain. I want to spend some time talking about applying prevention principles to improve pain management.

Apply Prevention Principles to Improve Pain Management

When we think about reviewing prevention principles, we know that primary prevention's goal is improving the overall health of the population by intervening before health effects occur. When we think of secondary prevention, we think of screening to identify diseases in the earliest stages. When we think about tertiary prevention, it's managing diseases post-diagnosis to slow or stop the progression. I want you to think of these prevention strategies in the context of pain management and in the context of preventing potential hearing loss.

Primary Prevention

The first thing we want to make sure we do is to educate the general public when we're speaking of pain management on the dangers of opioids. When you're thinking about preventing hearing loss for patients, there is specific education I'm sure you can provide. There was a researcher when I was working on my doctorate who did a lot of work with industrial workers, especially in the farming industry and encouraging them to use protective ear gear when they were using tractors and those types of things. Education on how to prevent hearing loss and to prevent or inform patients on the dangers of opioids is a good example of primary prevention. We want to make sure we increase and improve the education of healthcare professionals on the importance of comprehensive pain management with and without opioids.

Secondary Pain Prevention

When we think about secondary pain prevention, we want to make sure we're using proper words. We talked about pain versus comfort or discomfort. We've also talked about words that are being used to describe the pain, which may indicate the pain as a different type of pain than what we assumed it potentially could have been. We want to make sure that we identify the correct type or category of pain. I'm sure if you think about working with individuals who are suffering from hearing loss, there are different types and root causes behind hearing loss, and keeping that in mind as well. You want to make sure you understand the correct type of pain, or in your case, hearing loss you're dealing with. For us, it's important to know the acute, chronic, or if it's acute on chronic pain. Or if the categories, that nociceptive, neuropathic, and/or emotional or all three.

We also want to make sure we're improving the treatment of acute pain to make sure that we're not transitioning to chronic pain and adding more patients to that number of patients living with pain. Again, we want to make sure we're offering drug and non-drug pain management options.

Tertiary Prevention

As far as tertiary prevention, it's important to listen to our clients or our patients. When pain exists or hearing loss in your case, it's important to treat it with a comprehensive plan. We want to make sure that we create relationships with our patients and clients using honesty and respect to build trust. Because patients want to do the right thing, but they also want to feel that they can trust the providers that are helping them.

Therapeutic Communication Skills

I wanted to spend a little bit of time talking about using therapeutic communication skills. Some characteristics of therapeutic communication skills are respecting the client's personal values and beliefs. Allowing time to communicate with the patient. A lot of times, we're in a rush, and our patients feel that they aren't getting the attention they deserve. It is important to make sure they feel that they have time to express whatever's bothering them, whether it's a pain issue or a hearing loss issue that you're trying to manage. We want to make sure we use communication techniques to provide client support, active listening, oftentimes silence, proper body language, because a lot of times we know it's not what we say, but it's how we physically present when we're saying those things that can be disconcerting to patients. We also want to encourage clients to verbalize their fears. We can't get to the root of the problem without honest communication on both sides. As far as therapeutic communication with opioid misusers, we have to accept our patients for who they are, not who they want them to be. We have to use some empathy, sensing a client's emotions and reacting to them as if they were our own. We want to make sure we're authentic. There is nothing worse than a patient or client perceiving you to be fake and have ill intent when trying to help them manage an unfortunate situation that they're in.

We want to make sure we have unconditional positive regard. We want to show our patients that no matter what they do, we'll respect him or her, but our goal is to get them to a better place in managing their pain or their potential hearing loss issues that you may be working with.

Principles of Patient and Family Centered Care

Principles of patient and family centered care have become very important in the healthcare industry, particularly in acute care settings. There are four basic principles.

The first is information sharing, which means we need to share complete and unbiased information with each other. That is the providers with patients and families. We want to make sure there's participation in coming up with treatment plans. Patients and families build strength with experiences that enhance control and independence. We want to make sure we have collaboration, which includes policy and program development as well as delivery of care. We also want to make sure that we are treating all of our patients with dignity and respect, which is what most of us desire as human beings. When we think about patient and family centered care principles in pain management, when we think about information sharing, we want to make sure we're not holding the patient's past history against them. There are many patients who have struggled in the past with opioid dependency and misuse who do not want any type of opioid after surgery. We need to have available resources for those patients who verbalize they don't want to increase the risk of relapse and we have to have strategies available. Again this feeds into participation, where we allow our patients and families to play an integral role in building their care experience and providing suggestions, and helping us come up with a plan to manage their pain, their hearing loss, whatever issue we're dealing with. We want to make sure there's collaboration. The main focus of a pain management plan should be safety and prevention of transition to chronic pain. And again, the dignity and respect that most of us as human beings desire.

Reducing Anxiety Increases Comfort

We also have learned, I think and talked about in this presentation, that anxiety can also be a component that can increase pain. But reducing anxiety can also increase comfort.

We want to make sure we assess anxiety and its impact on pain. We want to assess and communicate about pain routinely with our families and patients, and that gets back to that patient and family centered care. We want to make sure we have an individualized plan with input from the child, parents, or families that are involved. We want to make sure patients and families ask about pain and comfort and don't feel like those questions can't be asked or answered. We also want to make sure we educate patients and families about pain management practices and options. We also need to educate them that pain and antianxiety medications may have serious side effects.

What Can We Do Now?

A few years ago, we did a survey on an inpatient unit where they were struggling with managing patients. We asked them what can we do to better manage your pain or discomfort. Surprisingly there were two things that were auditory-related that came up. A patient said that quieter would be nice. Some patients also said that again, quieter would be nice, keep the door shut to reduce the noise level in the room. If you've worked in acute care, you know a huge dissatisfier of patients is that there's a lot of noise in hospitals. We know there's a thing that's called alarm fatigue. There are lots of bells and whistles, doors, carts being pushed and pulled on the hallway. We have environmental services staff cleaning rooms, there's a lot of commotion going on. Hospitals have been working very hard to alleviate some of these complaints patients make about being overstimulated and having too much noise in hospitals. But I thought that was interesting that auditory related responses were put into these responses from patients.

One thing to keep in mind, more medication does not increase patient satisfaction. Actually hearing, is ironic based on the audience today, and listening does. The most important thing we can do is set realistic expectations for our patients.

Setting Realistic Expectations

When we're giving our patients unrealistic expectations of how to manage their pain, we sometimes know that we're setting them up for failure, which we need to stop doing. Our patients have expectations or goals. They want to make sure we understand that their past experience is a powerful contributor to their current state. That therapeutic communication and practical explanations are important. Most importantly, they just want us to listen to them. Now we as healthcare professionals also have expectations. Some of us still feel that patients should do what we tell them to do. Not because we know what's best for them, but we know this approach doesn't work.

Adherence

We traditionally call it patient behavior compliance, but now we're starting to use the word adherence. When we want to improve the adherence of our patients, we want to make sure that patients have the right information and know-how to adhere. We want to help patients believe in their treatment and become motivated to commit.

We want to assist patients to overcome practical barriers to treatment adherence and develop a workable strategy for long-term disease management, including management of chronic pain, diabetes, or hearing loss, whatever the issue may be. What are realistic expectations? We have to let our patients know, especially those experiencing pain, that injuries are painful, anxiety can increase the perception of pain. We have to have a balance between safety and comfort. Response to medication varies by individual. Reduction of pain by 30 to 50% is more achievable than eliminating it. We used to tell patients, "Oh, you're not going to have any surgery after your procedure," and we just can't do that anymore because we can't guarantee zero pain after procedures. Then we also want to make sure we continually assess pain management and control and their functional improvement. Again, are you able to walk and move and cough and do all those things?

Case Study: Summary

To summarize our case summary, and a lot of this we've talked about throughout the presentation. The patient probably has some nociceptive with neuropathic and emotional pain components. There may be some health issues that could impact her pain treatment plan. She did have some alcohol misuse. She may or may not have had asthma. These are just some other things not specific to this particular case study, but some things to keep in mind for patients who are having pain issues. If they have these also these underlying issues based on where those mu receptors are in the body, that may cause some other issues when trying to manage the pain. She may have some opioid misuse and possibly the use of recreational drugs. We don't want to assume anything, but if she has limited resources, that may be something we need to take into consideration. We always want to make sure we're including non-opioid pain management options. We want to know what is their treatment goal. What is her goal for her pain management? A few things to remember as we close. We want to make sure we set realistic expectations for our patients who are experiencing pain. Or even your patients who are, you're managing potential hearing loss. We want to make sure that we understand that the opioid epidemic is multifaceted, and there's not just one solution to addressing the problem. When we're treating pain, the goal is to assess and treat the pain appropriately. We know that ongoing assessment of side effects is a key component of a quality pain management plan. We know that therapeutic communication skills are an important part of building trusting relationships with our clients.

References

Ansari, A., Rizk, D., and Whinney, C. Multimodal Pain Strategies Guide for Postoperative Pain Management https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/globalassets/clinical-topics/clinical-pdf/ctr-17-0004-multi-modelpain-project-pdf-version-m1.pdf

Arnstein, P. (2010) Clinical Coach for Effective Pain Management, F.A. Davis Co. page 62

Campbell, K. (2018). Do opioids hurt hearing? The ASHA Leader, 11:49-56.

Chiu, R., Gordon, D., and de Leon-Casasola, O. et Al (2016). Guidelines on the Management of postoperative pain, The Journal of Pain, 17(2); 131-157.

Dimatteo, M., Haskard-Zolneirerk, K., and Marti, L. (2012). Improving patient adherence: a three-factor model to guide practice, Health Psychology Review, 10(1): 74-91.

Ferrell, B. R. (2007). Reducing barriers to pain assessment and management: An institutional perspective, Journal of Palliative Medicine, 10 (1S), S15-S18.

Hilliard, P. E., Waljee, J., Moser, S., Metz, L., Mathis, M., Goesling, J., … Brummett, C. M. (2018). Prevalence of Preoperative Opioid Use and Characteristics Associated With Opioid Use Among Patients Presenting for Surgery. JAMA Surgery, 153(10), 929–937.

Kadiri, J., Hayets, B., Lev, M., Sajed, D., and Miller, E. (2018). Case presentations of the Harvard Affiliated emergency medicine residencies, The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 55(3): 411-414.

Mallick-Searle, T. and St. Marie, B. (2019). Cannabinoids in Pain Treatment: An Overview, Pain Management Nursing, 20, 102-7-112.

McKee, M., Meade, M., Zazove, P., Stewart, H., Jannausch, M. and Ilgen, M. (2019). The relationship between hearing loss and substance use disorders among adult in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(4): 586-590.

Nguyen, K., Mowlds, D., Lopez, I., Hosokawa, S., Ishiyama, A., and Ishiyama, G. (2014). Mu-opioid receptor (MOR) expression in the human spiral ganglia, Brain Research, 1590: 10-19.

Proctor-Williams, K. (2018). The opioid crisis on our caseloads, The ASHA Leader, 11:42-48.

Rawool, V. (2016). Audiological implications of the opioid epidemic. The Hearing Journal, 10:11-12

Stranden, M., Solvin, H., Fors, E., Getz, L., and Helvik, A. (2016). Are persons with fibromyalgia or other musculoskeletal pain more likely to report hearing loss? BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 17: 1- 10.

Citation

Holmes-Walker, S. (2020). Pain management and the opioid epidemic: what you need to know. AudiologyOnline, Article 27254. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com