Learning Outcomes

After this course, learners will be able to:

- Define stigma in hearing healthcare and its root causes.

- Describe how improved hearing aid product design addresses stigma.

- Describe how better person-centered communication addresses stigma in hearing healthcare.

Introduction

Let’s start with a story, one familiar to most clinicians who work with older adults. In a quaint suburban neighborhood, Mrs. H. sat on her porch, soaking in the warmth of the morning sun. Despite the vibrant colors of the flowers in her garden, there was a muted quality to her day-to-day existence. For many years, as she grew older, Mrs. H. coped with many chronic, age-related conditions including gradual hearing loss -- a silent intruder that crept into her life with the passage of time.

As she watched the world go by, Mrs. H’s family and closest companions couldn't help but notice the subtle changes in her interactions with neighbors and friends. Conversations became strained and invitations to social gatherings dwindled. Her once lively conversations with families and friends now felt like echoes of a distant past, lost in the void of her declining hearing. She now spent more time alone listening to the music of her youth and watching old movies – Bing Crosby musicals were her favorite.

Despite her struggles with daily communication, apparent to everyone around her, Mrs. H. remained steadfast in her obliviousness to her condition. Years later, after some cajoling from her family, and despite her fears that hearing loss was a harbinger for dementia, Mrs. H. had her hearing assessed by a local audiologist who kindly informed her she needed hearing aids. When the audiologist told her that she could use the type that no one can see, Mrs. H. had, at long last, agreed to acquire hearing aids.

Yet, Mrs. H’s journey to better hearing was not without its challenges. The stigma surrounding aging, hearing loss, and hearing aid use continued to loom large, casting shadows of doubt and shame. Even after acquiring hearing aids, Mrs. H. continued to grapple with feelings of inadequacy and fear of judgment, fearing that her condition would define her worth in the eyes of others. Six months after obtaining hearing aids, she seldom wore them. Yes, they were invisible, but simply taking the time to place them into her ears made her feel old. Maybe she was vainer than she cared to admit? All the negative feelings associated with growing older and trying to deal with her hearing loss left her overwhelmed and vulnerable. It took a selfless act of a close friend to move her back into action. Mrs. H’s friend managed to broker a follow-up visit with her audiologist for some help.

Amidst her internal whispers of doubt, Mrs. H., with the support of her audiologist, confronted the stigma head-on, advocating for awareness and understanding within her circle of family and close friends. Through her courage and vulnerability, with some valuable guidance from her audiologist, Mrs. H. transformed the internal narrative surrounding her hearing loss, turning whispers of stigma into echoes of empowerment. Today, with a more positive mindset, she wears her hearing aids every day and actively participates in conversations again.

As this vignette illustrates, stigma is pernicious and insidious; it rears its ugly head throughout the patient journey. From resistance to getting a hearing test to consistently wearing hearing aids, stigma is a major obstacle inhibiting help seeking, hearing aid acquisition and daily use of them. The objective of this article is threefold: 1.) to review the characteristics of the stigma associated with hearing loss, 2.) through a literature review, assess the effect stigma has on attitudes and behaviors of persons with hearing loss, and 3.) discuss the roles of the hearing aid manufacturer and the clinician in addressing stigma and how consequences of stigma can be more effectively addressed and overcome.

I. The Harmful Effects and Prevalence of Stigma

Approximately 85% of adults in the US who self-report trouble hearing fail to seek treatment (Humes, 2023). Additionally, there is an average eight-year delay in seeking help (Simpson et al., 2019), as well as evidence of low average daily use rates (Dillon et al., 2020). There are, of course, several reasons behind these troubling statistics, including the high out-of-pocket expenses associated with treatment, perceived lack of benefit, and the inconveniences associated with acquiring hearing aids. Perhaps one of the most pernicious but least understood causes associated with these numbers is stigma.

Many individuals experience the stigma associated with hearing loss and aging. According to a recent ASHA-sponsored online survey of 784 adults with self-reported hearing difficulties, 58% reported they experienced at least one of the following forms of stigma: feeling like an outcast, feeling less than, feeling judged, being seen as less than intelligent, not have achievements recognized, and being labeled or talked down to because of their condition. Moreover, 82% of respondents said that stigma had a significant impact on their daily lives, while 42% of respondents said it had a significant impact on important relationships.

Chundu et al. (2020) examined the social representation of hearing loss in four countries, including the United States. Using a cross-sectional survey design, they found that 84.0% of respondents have a negative connotation of hearing loss, with a mere 5.3% reporting a positive view of hearing loss. A more detailed analysis of the drivers of these negative views determined that aging, social isolation, and a negative mental state were key components of these negative connotations associated with hearing loss. In another similar study that examined the social representation of hearing aid use, Chundu et al. (2021) found that 54.5% of American respondents had a negative view of hearing aids, while 34.6% had a positive view, and 10.9% were neutral. Among the most common drivers of negative connotations associated with hearing aid use is appearance and design, along with cost and the appointment time associated with acquiring hearing aids. Finally, a survey of hearing aid non-owners indicated that 21% of hearing aid non-owners cited stigma as a barrier to pursuing hearing aids – even when lower cost over-the-counter options were made available to them (Williams, 2022).

In short, results of these surveys indicate that persons with hearing loss and hearing aid wearers are perceived in a negative light – they are often considered old, less sociable, and more disabled than younger, normally-hearing members of society.

II. Definitions and Theories of Stigma

According to Sartorius (2007), there are several health conditions that are stigmatized – e.g., schizophrenia, AIDS, venereal diseases, leprosy, and certain other skin diseases. People who have such conditions are often discriminated in the health care system, they usually receive much less social support than those who have non-stigmatizing illnesses and – what is possibly worst – they have serious difficulties navigating their daily existence because of how they internalize the way others negatively view their condition. Among the most common stigmatizing conditions, however, are those associated with aging. This list includes cognitive decline, physical disabilities, and, of course, hearing loss. Given the rapidly aging population and the prevalence of hearing loss in older adults, it is remarkable that stigma, and its effect on hearing aid uptake, is not well understood by many clinicians.

Put simply, a condition is stigmatizing if it gives rise to negative stereotypes and discrimination against those with the condition. It is a process by which people with a specific condition or appearance experience a lowering in social status as a result of that condition or appearance (Bos et al., 2005). It is generally believed there are two overarching components associated with any stigmatized condition. Self-stigma, which is related to how stigma affects the individual with the condition, and public stigma, a term used to describe the general public’s attitude and bias surrounding the condition.

Clinicians can go all the way back to 1963, during the waning days of the Kennedy Administration to find the seminal work on the topic of stigma. In the oft-cited book entitled, Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, sociologist Erving Goffman defined stigma as “any attribute that is deeply discrediting and reduces the individual from a whole and usual person to a tainted and discounted one.” Building on this work, Jones et al. (1984) identified six dimensions of stigma. These dimensions include concealability (i.e., the extent to which a stigmatized condition is visible to others), “course of the mark” (i.e., the extent to which a stigmatized condition persists over time), disruptiveness (i.e., the extent to which a stigmatized condition interferes with smooth social interactions), aesthetics (i.e., the potential for a stigmatized condition to evoke a reaction of disgust), origin (i.e., whether a stigmatized condition is believed to be present at birth, accidental, or deliberate), and peril (i.e., the extent to which a stigmatized condition poses a personal threat or potential for contagion).

Twenty-five years ago, the late Canadian audiologist Raymond Hétu described the stigma associated with hearing loss as having two forms: The first describes the stigmatization process itself, while the second form of stigma describes the normalization process. According to Hétu (1996), during the stigmatization process (the first form) persons with hearing loss are apt to experience shame and embarrassment because they lose their sense of belonging to a social group. Stigmatization results when people with hearing loss interact with normal-hearing individuals and communication breakdowns and other maladaptive behaviors associated with an inability to communicate in social situations occur. These feelings of inadequacy that stem from these unsatisfying social interactions, in turn, result in embarrassment, shame and guilt, which lead persons with hearing loss to conceal their hearing loss from others. Ultimately, this leads many persons with hearing loss to withdraw from social activities and become isolated.

The second form described by Hétu is the normalization process, which is where persons with hearing loss can address and overcome the feelings of embarrassment, shame and guilt, and to restore a more favorable social identity. The normalization process is facilitated by a clinician. The first stage of the normalization process involves meeting and interacting with other persons with hearing loss in order to share experiences. This activity demonstrates that other persons with hearing loss have experienced many of the same feelings associated with their condition. During the second stage of the normalization process, persons with hearing loss are asked to interact with others who have normal hearing, and they are encouraged to use communication strategies that may have been acquired during the first stage to optimize group communication performance. It is during the second stage that persons with hearing loss will gain more confidence in their communication ability and restore a more favorable social identity.

Major and O’Brien (2005) discussed the psychological effects of social stigma through the lens of the identity-threat model of stigma. Their model posits that situational cues, collective representations of one's stigma status, and personal beliefs and motives shape appraisals of the significance of stigma-relevant situations for well-being. According to their model, a person’s identity is threatened when stigma-inducing stressors are believed to be potentially harmful to one's social identity and exceed one's ability to cope effectively. Moreover, when one’s identity is threatened it creates undue stress, which leads to poor self-esteem, failure to seek help for their condition, withdrawal, isolation and other negative outcomes. Identity threat perspectives help to explain the tremendous variability across people, groups, and situations in responses to stigma.

Another framework used to describe stigma and its impact on the person with hearing loss and society writ large is the modified labeling theory outlined by Southall et al. (2014). According to the modified labeling theory, learning stereotypes about behaviors and attitudes is an essential component of how a condition becomes stigmatized in society. Society comes to understand that people with certain conditions are devalued in society and the general public distances itself and discriminates against individuals with this condition. The modified labeling theory holds that once society can identify distinguishing differences (labeling) in individuals with various conditions, they are able to affix negative attributes to those individuals with the condition (stereotyping) in an oversimplified or biased manner. This stereotyping leads to a separation of the individual with the condition from those in the general public who do not have the condition. This separation leads to reduced standing in social status and discrimination. The labeling and stereotyping associated with hearing loss can influence help-seeking behavior.

David and Werner (2015) conducted a scoping review of the relationship between stigma and hearing loss and hearing aid use. Their analysis found 21 peer-reviewed publications that described the stereotypes associated with hearing loss and hearing aid use. One trend across several of the studies in their review article was that many people with hearing loss choose not to wear hearing aids because of ageist stereotypes. Following this scoping review, David et al. (2018) conducted semi-structured interviews with 11 older persons with hearing loss. Self-stigma was present in the lives of all 11 study participants. The authors observed the following three core dimensions of stigma in all participants: A.) cognitive attributions: fear of being labeled as old, stupid, and crippled; B.) emotional reactions: feelings of shame, pity, and being belittled, and C.) behavioral reactions: concealment, distancing, and adapting to hearing aids. On a positive note, the acquisition of hearing aids emerged as having a significant influence on all three dimensions of stigma. Similar results were found in another recent scoping review by Ruusuvuori et al. (2021) who posited that the stigma associated with hearing loss consistently involves two key components: 1.) Fear of diagnosis, and 2.) Visibility of treatment. More recently, a systematic review by da Silva et al. (2023) summarized that issues related to stigma and hearing loss can be divided into three themes. One, social stigma effects self-stigma, which is related to how society views the disability of hearing loss and how those views shape the individual’s perception of stigma. Two, hearing loss-related stigma may cause several negative emotions in the person with hearing loss, including shame and embarrassment. Three. stigma influences decision-making around initial acceptance of hearing loss and search for treatment options.

Finally, leaning heavily on the identity-threat model of Major and O’Brien (2005), Ekberg & Hickson (2023) outline a study that will be published in an upcoming special issue of the International Journal of Audiology that attempts to describe how stigma is experienced in adults with hearing loss and how the lived experience of hearing loss stigma is related to hearing aid use. In their first recently published-ahead-of-print piece for this special issue, Nickbakht et al. (2024), analyzed stigma from the perspective of persons with hearing loss, their families, and HCPs. They found that stigma-induced identify threat is found for both hearing loss and hearing aid use in all three groups. They determined that HCPs focused on the stigma of hearing aids more than hearing loss. In contrast, persons with hearing loss focused more on the stigma of hearing loss, while their family members experienced little stigma associated with either. These results have important clinical implications that we discuss in Section IV.

The above-mentioned studies and review articles can be summarized as follows: Stigma is not just experienced by aging individuals with hearing loss, instead it directly reflects the quality of relationships and the way in which society reacts to those who have hearing loss. Moreover, the preponderance of research indicates stigma is strongly linked to aging and hearing loss, and often leads to withdrawal, social isolation, and a negative self-image. Table 1 summarizes some of the most important causes of hearing loss stigma, the effects on the individual, the impact on society, and different ways to overcome it.

Causes of Stigma | Effects of Stigma on the Individual | Impact of Stigma on Society | Overcoming Stigma |

-Fear of aging -Fear of disability -Lack of awareness of condition -Misconceptions associated with condition -Existing stereotypes related to the condition -Media portrayal of hearing loss and aging in a negative light -Cultural attitudes surrounding hearing loss and aging

| -Social isolation -Low self-esteem -Anxiety and depression -Avoidance of seeking help -Poor relationships, especially in social circles -Assumptions of cognitive decline -Feelings of shame and guilt -A threat to social identity -Reluctance to acknowledge hearing difficulties - A desire to conceal condition -Low usage of hearing aids

| -Hinders social cohesion -Increased healthcare costs due to delated diagnosis and treatment of hearing loss -Undermines relationships across generations and social circles -Psychological distress of individuals within family or social circles

| -Education and awareness campaigns -Promoting positive representative of aging and hearing loss -Supporting participation in society -Design hearing aids that address stigma -Positive beliefs associated with the use of hearing aids |

Table 1. A summary of the causes and effects of hearing loss stigma, and how to combat it.

Unknowingly Reinforcing Stigma by Focusing on the Attributes of Stigma

In what is considered a landmark qualitative study on the stigma of hearing loss, Wallhagen (2010) proposed that stigma was related to three interrelated experiences: alterations in self-perception, ageism, and vanity. Examples of each of these three interrelated experiences are summarized in Table 2.

Alterations in self-perception | Ageism | Vanity |

Able Whole Smart Social Young “With it”

| Fear of being perceived as old, decrepit, and unable to be independent | Bothered by the appearance of something that makes one feel old, less sociable or disabled

|

Table 2. A summary of the three interrelated experiences associated with the stigma of hearing loss (Wallhagen, 2010).

Wallhagen (2010) documented the pervasive nature of stigma in relationship to hearing loss and hearing aid use and the close association of this stigma to ageism. Perhaps Wallhagen’s most important contribution to how we understand the stigma of hearing loss is this: Communication partners, the media, and hearing care professionals all tend to reinforce stigma in the way they communicate and interact with the person with hearing loss. Consequently, through their attempts to overcome the effects of stigma, by calling attention to a person’s vanity, they actually unknowingly reinforce the stigma. In accordance with Wallhagen’s vicious cycle, the reinforcement of stigma is a common occurrence by hearing aid manufacturers and hearing care professionals in two ways.

- Advertisements for today’s modern hearing aids emphasize small sizes, cosmetic appeal and invisibility. Although a focus on these features may increase the chances of some individuals to seek treatment, it assumes that hearing aids are in fact stigmatizing and need to be hidden by the wearer.

- The same holds true for hearing care professionals who focus on the discrete size and invisibility of hearing aids. By focusing on how well-hidden the devices can be, rather than promoting hearing aids as a means to a more active and engaging life, hearing care professionals reinforce the stigma that hearing loss must remain hidden from others.

III. The Role of the Hearing Aid Manufacturer: Modern Product Design

As already outlined, the stigma related to hearing loss and hearing-loss treatment is complex and multifaceted. However, there is no doubt that the mere physical design of hearing aids plays an important part in the stigma related to hearing aids.

Performing an internet search for “hearing aids” and looking at the photos that pop up as search results, it is no wonder that “hearing aids” by many people are associated with a big and awkward piece of electronic equipment – often in a strangely colored and poorly designed shell – that is placed inelegantly behind (or on) the ear. This image of modern prescription hearing aids is patently false, but the stigma is kept alive by cheap personal sound amplification products (PSAPs) and corresponding products that basically have nothing to do with hearing aids. While certain modern hearing aid styles, like Receiver-In-the-Canal (RIC) and Behind-The-Ear (BTE) form factors, also are placed behind the ear, they have undergone a development in design (and audiological performance) that makes it almost meaningless to compare them with the devices that pop up on most internet searches. Unfortunately, these are often the photos potential wearers see when they, as part of their initial help-seeking, conduct their first searches for “hearing loss” and “hearing aids.”

Signia’s Approach

At Signia, the possibility to address hearing aid stigma via the physical design of the hearing aids has for long been a strong focus point. Besides constantly refining the design of traditional hearing aid form factors that have been used for decades, Signia has also taken the design of hearing aids in completely different directions, offering new and innovative form factors that, in different ways, challenge and tackle the traditional hearing aid stigma.

In broad terms, Signia has used three fundamentally different design approaches to address stigma: Concealment, De-identification, and Normalization. In the following, we will explain the principles behind each of these approaches and highlight three unique Signia form factors that have been developed according to these principles.

Concealment – Signia Silk

The most well-known approach to address stigma through design is to reduce the visibility of the hearing aids when placed in the ear of the wearer. The desire to conceal the hearing aids has been a main driver for decades of development efforts to make the physical hearing aids as small and invisible as possible. This work has resulted in the introduction of very small custom hearing aid form factors, like Completely-In-Canal (CIC) and Invisible-In-Canal (IIC), which are almost impossible to see from the outside when positioned in the ear. As Wallhagen (2010) suggests, a focus during the hearing aid selection process on concealment per se may reinforce stigma. Consequently, there are several performance advantages of the IIC and CIC styles that should be a point of emphasis when patients are weighing their options. These performance advantages may include a reduction in wind noise, ease of insertion and removal from the ear, and better localization ability due to the maintenance of the pinna effect.

Signia has been at the forefront when it comes to the development of small and almost invisible hearing aids, like CICs and IICs. However, Signia has taken some steps further with the introduction of the Signia Silk form factor (see Figure 1, left). Unlike other small devices which can be concealed in the ear canal, Silk has an outer exchangeable soft sleeve which follows the normal curvature of the ear canal and provides a comfortable instant-fit without the need for a custom tip. Furthermore, the newest generation of Silk offers rechargeability and Binaural OneMic Directionality. Combining these features with the concealment effect in a full prescription hearing aid makes Silk a strong asset in combatting hearing aid stigma.

As mentioned previously, while reducing the size and visibility of hearing aids may reduce the stigma for the individual wearer, the promotion of “small”, “discrete” or “invisible” hearing aids as something desired may add to the hearing aid stigma in the general population because it may contribute to a conception that hearing aids should not be seen, and that visible hearing aids are undesired. This suggests that concealment should not be the only way to address stigma via design, and accordingly, the two other Signia design approaches, de-identification and normalization, are just as relevant because they address stigma in a completely different way.

De-identification – Signia Styletto

This approach involves completely rethinking the hearing aid design by introducing different physical shapes and by modifying or removing some of the most identifiable physical features associated with traditional hearing aids.

The Signia Styletto is a good example of a successful application of the de-identification approach (see Figure 1, middle). While positioned behind the ear and offering a receiver in the ear as the more traditional RIC hearing aids, the Styletto has introduced a very different, slimmer and more elongated design, which separates it markedly from traditional RIC designs. Furthermore, the shell does not include any buttons that can operated by the wearer. All interaction with the hearing aids, such as volume adjustment and program change, is performed via an app. However, importantly, the Styletto offers the most advanced adaptive signal processing, and most wearers will notice that their need to operate the hearing aids is quite limited.

Normalization – Signia Active Pro

The third design approach to address hearing aid stigma is based on the idea of redesigning a stigmatizing device to become indistinguishable from a non-stigmatizing target device. In case of hearing aids, this approach is benefitting from the fact that wireless earbuds were introduced to the consumer electronics market around a decade ago. This technology was quickly adapted by a wide variety of consumers to stream sound from their smartphones without the hassle of wires or large over-the-ear headphones. By adapting the earbud design, hearing aids can be worn and operated by those with stigma in a manner that they would perceive to be better aligned with their pre-conceived societal norms of an observer.

The normalization approach and the inspiration from consumer electronics was key in the development of the Signia Active Pro form factor (see Figure 1, right). On the outside, the Active Pro hearing aid looks like an earbud, and it offers all the functionality of an instant-fit earbud. But audiology-wise, it is indeed a full-fledged prescription hearing aid with all the advanced functionality of a premium hearing aid.

Figure 1. Three different Signia form factors designed on the principles of concealment (Silk, left), de-identification (Styletto, middle) and normalization (Active Pro, right), respectively.

Investigating the Perception and Effect of Innovative Form Factors

Potential wearers’ perception of the three innovative Signia form factors, Silk, Styletto and Active has been investigated in different ways. In a study done in connection with the launch of the Styletto form factor, Hakvoort & Burton (2018) presented data from a survey of 508 respondents within the Styletto target group where the vast majority (92%) did not own hearing aids. When presented with two photos showing five different hearing aid form factors, with the only difference being that one photo included Styletto, while Styletto was replaced by Signia Motion (BTE) in the other photo, 84% of the respondents stated that they would be more likely to enter a hearing center offering the selection including Styletto. This finding suggests that just by adding an innovative form factor – in this case offering de-identification – to a portfolio of more traditional form factors, the interest of potential wearers to enter a hearing aid clinic will increase.

In the same study, when presented with a photo of the Signia Motion (BTE) and the Signia Pure (RIC) and given the information that both form factors would meet the requirements of their hearing loss, 57% of respondents stated they would be most likely to buy Pure, while 25% stated “none” when asked about their buying preference. However, when showing a photo with the same two form factors, but this time with Styletto added, 65% of the respondents said they would be most likely to buy Styletto, and, interestingly, now only 10% of respondents said they would buy none of them. Thus, not only was Styletto the most preferred form factor when compared to BTE and RIC hearing aids. It also substantially reduced the group of respondents who stated a lack of interest in buying any hearing aid.

A similar finding was made by Marcoux et al. (2023) who reported the results from a survey of 384 Canadian respondents with a self-reported hearing loss. In this survey, the respondents were first presented with a photo of three traditional form factors offered by Signia: Pure (RIC), Motion (BTE) and Insio (ITC). The respondents were asked whether they would consider purchasing one of the hearing aids or none of them. In a second round, the respondents were presented with the same three traditional form factors but this time adding the three innovative form factors: Styletto, Silk and Active Pro. The results showed that addition of these form factors reduced the share of non-buyers by 21%. That is, the addition of the innovative form factors increased the interest in buying a hearing aid.

In another part of the same Canadian survey, reported by Marcoux et al. (2022), the respondents were presented with pictures of different types of hearing aids and different types of earbuds, and for each form factor, they were asked whether they thought that particular style was a hearing aid. While traditional hearing aid form factors such as RIC and BTE were identified as hearing aids by around 80% of the respondents, the association frequency dropped to 53% for Signia Silk, and for Signia Active Pro it was only 27%. This is close to the association frequency of 22% observed for the Apple Airpod, and it provides a clear indication that the normalization approach used in the design of Signia Active Pro has had the intended effect.

The results presented here suggest that rather than just focusing on trying to hide hearing aids, HCPs are advised to emphasize the stylishness of various designs as well as the potential performance advantages of them. Rather that position form factors as simply a BTE, CIC or IIC, HCPs, moreover, would be wise to discuss specific design elements. For example, talk about the elongated, slim look and the assorted color options of the Styletto, instead of simply referring to it as a mere RIC. Ultimately, all the ingenuity and innovation that manufacturers place into form factor design depends on how well HCPs communicate the benefits of these myriad styles with patients – which is the topic of the next section.

IV. The Role of the Clinician: Delivering Holistic Person-Centered Care

Although the stigma associated with hearing loss is a problem that persists in both individuals and society as a whole, HCPs are best equipped to address stigma at the individual level. This final section discusses several tactics which can be employed by HCPs during routine appointments to address the stigma of hearing loss and hearing aid use. Here, we try to provide some practical guidance to HCPs on how stigma research and hearing aid design considerations can be applied during clinical assessment and treatment.

Overcoming the obstacles associated with stigma require more than new and innovative form factors. It requires a concerted effort from HCPs to confront head-on the damaging effects of stigma. It is important to be aware that many of the stereotypes associated with hearing loss and hearing aid use are also linked to aging. Individuals and society in general oftentimes have negative beliefs about both hearing loss and aging that drive many of these stereotypes. Since hearing loss is one of the inherent qualities associated with aging, perhaps the first step in addressing stigma in the clinic is being more aware of the abundance of negative beliefs also associated with aging. As Table 3 illustrates, there are many harmful and false stereotypes related to aging.

Given the prevalence of these age-related stereotypes, Levy (2022) suggests it is helpful for all healthcare professionals who work with older populations to be aware of these false and harmful stereotypes and refute them with facts. Table 3 also outlines facts that can be applied to shifting one’s own personal beliefs about aging as well as those of patients encountered in the clinic. We believe that when HCPs express more positive beliefs about their core clientele: older adults, they can begin to shift the attitudes of help seeking persons with hearing loss from negative to positive.

Harmful and False Stereotypes Associated with Aging | Facts to Refute Stereotypes |

Older workers are ineffective in the workplace | Older workers take fewer days off, have strong work ethics and have innovative ideas (Borsch-Supan (2013) |

Older people are fragile, and don’t contribute to society | Older people more often work in helping professions and volunteer more time to community organizations compared to younger adults (Konrath et al., 2013). |

Cognition inevitably declines as people age | Some types of cognition, namely metacognition, semantic memory, and crystallized intelligence, do not decline with age (Levy et al., 2012). |

Older persons experience dementia | Dementia is not a normal part of aging. Only 3.6% of US adults between the ages of 65 and 75 have dementia (Wolters et al., 2020) |

Table 3. Some of the most common stereotypes related to aging and facts that refute them. Adapted from Levy (2022).

Levy's research on aging, published in more than 80 peer-reviewed articles, focuses on how societal and individual attitudes towards aging impact the health and longevity of older adults. Her work demonstrates that positive perceptions of aging can lead to better physical and mental health outcomes, increased longevity, and improved functional abilities. Conversely, negative stereotypes about aging can contribute to poorer health outcomes, increased disability, and even reduced life expectancy. Levy’s studies emphasize that a more positive view of aging and can improve the well-being of the elderly. Since hearing loss is so intertwined with aging, we believe those principles can be applied by HCPs in the clinic in how they address stigma in persons with hearing loss.

Table 4 summarizes three common stereotypes associated with hearing loss in older adults and how HCPs can refute each with facts. The lesson outlined in Table 4 is simple: Any false or harmful stereotype uttered in the clinic by a help seeking person should be debunked candidly and earnestly with facts. Further, as Nickbakht et al. (2024) recently demonstrated, since persons with hearing loss appear to be bothered more by negative stereotypes associated with hearing loss than the stigma associated with hearing aid use, HCPs would be wise to address these concerns early on during the assessment and case history before hearing aid candidacy is even determined. The stigma associated with hearing loss requires candid, direct conversation about it with a keen focus on facts that refute these stereotypes.

Harmful and False Stereotypes Associated with Hearing Loss | Facts to Refute Stereotypes |

Wearing hearing aids is an inevitable part of aging | By protecting your hearing, having a positive outlook, and living a healthy lifestyle, it is possible to maintain near-normal hearing as you age (Chasteen et al., 2015). |

Hearing aids make me look old | Hearing loss can occur at any age. Having an untreated hearing loss can make you look older |

I don’t need hearing aids because my loss is normal for my age | Even a mild hearing loss can adversely affect communication, relationships and social life |

Table 4. Some of the most common stereotypes related to hearing loss and facts that refute them.

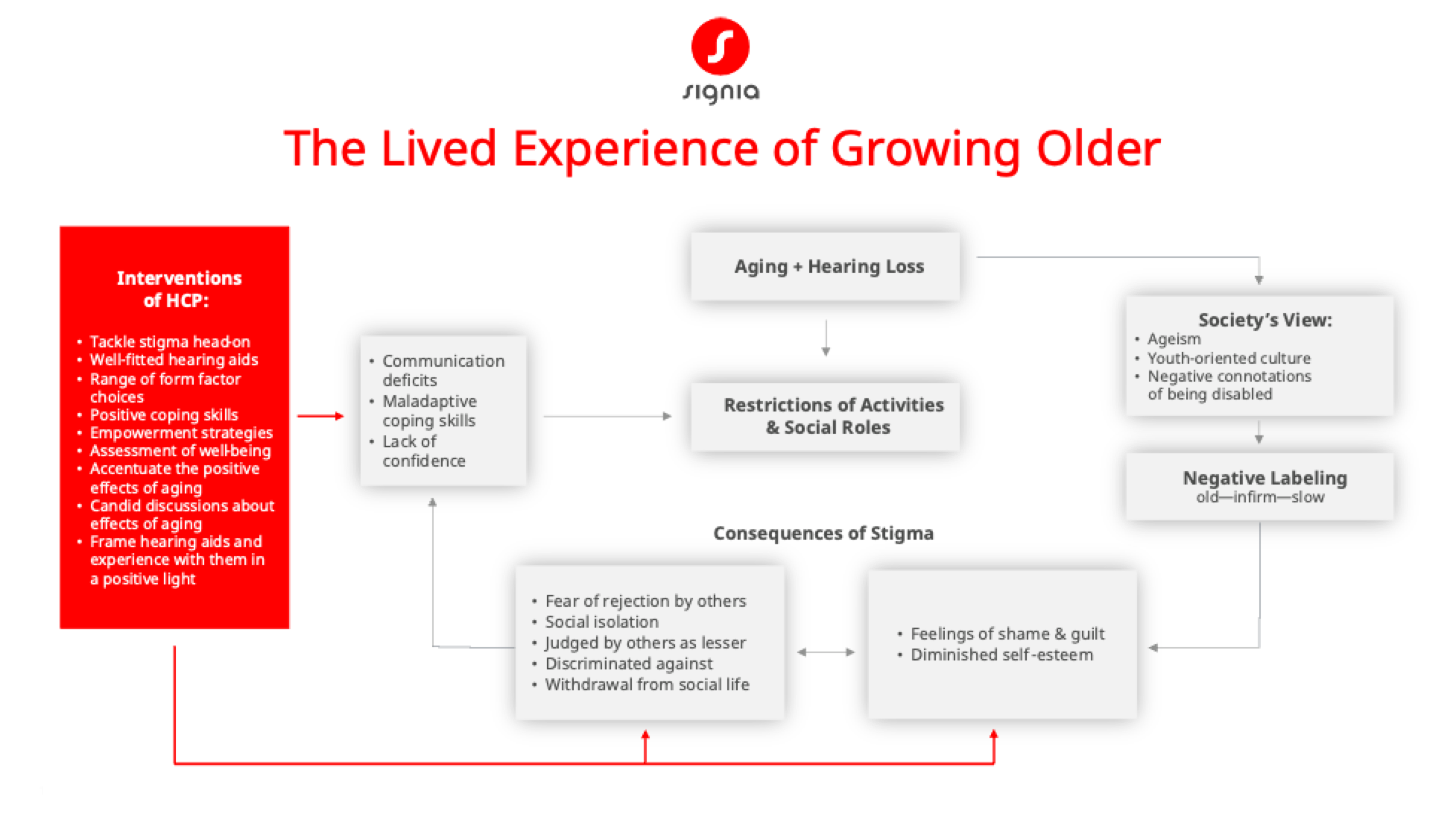

As the first part of this article describes, the stigma associated with hearing loss is a multifaceted issue influenced by various cultural, social and psychological factors. These complexities, which include social perceptions and stereotypes, like ageism, and communication barriers are summarized in Figure 4. This lived experience of hearing loss has several important considerations, as Figure 4 illustrates, including various intervention strategies (red box) orchestrated by the HCP. By applying several of these intervention strategies during any part of the patient journey, we believe, the negative effects of stigma can be overcome. It is in that spirit that we conclude this article by providing four strategies HCPs can apply to address the stigma of hearing loss and frame the condition in a more positive light.

Figure 2. The lived experience of growing older and the complexities associated with the stigmas of hearing loss and aging. The red box summarizes a variety of interventions that HCPs can apply to addressing the consequences of these stigmas.

Accentuate the Positive

As noted in Tables 1-3 there is considerable negativity bias associated with hearing loss and aging. Two recent studies demonstrate that many of these negativity biases can be counteracted by HCPs when they simply focus on the positive attributes of hearing aids and the positive experiences associated with hearing aid use. The two studies explored whether positive narratives provided by a hearing care professional to a person with hearing loss would influence their outcomes with the hearing aids.

In the first study, Rakita et al. (2021), during a routine hearing aid fitting appointment, exposed a group of 19 adults aged 54 to 81 to a different narrative condition: positive, negative, or neutral. The positive narrative consisted of the use of language that affirmed that hearing aids had a “rich and natural” sound quality, and that acclimatization would occur rapidly. Results showed that communication of a positive narrative about hearing aids before a hearing aid fitting led to better speech-in-noise performance on the QuickSIN and led to the perception that acclimatization to the hearing aids would occur faster.

In a similar study, Lelic et al. (2023) randomized a group of 21 older adults into one of two groups: a control group and a Positive Focus group who were asked to repeatedly focus on their positive hearing aid experiences using a smartphone app. The Positive Focus group were given examples of positive listening experiences (e.g., great communication at a party or hearing birds in the forest) and they were asked to report these positive experiences as much as possible using the app. Results showed that hearing aid outcomes were significantly better for the Positive Focus group compared to the control group. Together, these studies demonstrate that HCPs can shape wearers’ attitude and mindset, and consequently, hearing aid outcomes in a favorable way by simply accentuating positive attributes of hearing aids and their experiences that result from wearing them.

Eliminate the Negative

Appearance and design are one of the most common hearing aid traits that people recall when asked about using hearing aids (Chundu et al., 2021). This highlights the importance of addressing the stigma of hearing aid use. However, as suggested by Wallhagen (2010) emphasizing concealment and invisibility traits risks perpetuating the stigma. To avoid this dilemma, it is advisable to instruct all prospective wearers on their style (form factor) and color options and avoid language related to concealment and invisibility. Similar to how a person might purchase a luxury product like a handbag, shoes or kitchen appliance, show a range of options and focus on style or design considerations. Think of hearing aids more like a luxury product with specific design qualities and less as a medical device with stodgy features.

Latch on to the Affirmative

As shown in Figure 2, restrictions on activities and social life are two of the conditions associated with the lived experience of growing older. These restrictions often lead to several negative consequences as outlined in Figure 2. As suggested by Gotowiec et al. (2022), HCPs can intervene by creating a sense of empowerment in persons with hearing loss who might be coping with these restrictions. By giving individuals more control and autonomy in their work and social lives, it can lead to increased motivation, wellness and quality of life.

Empowering individuals with hearing loss can improve their quality of life, communication abilities, and social inclusion in the following ways:

- Self-Advocacy and Control: Empowering individuals to advocate for their own needs, whether through technology, workplace accommodations, or social support, enhances their sense of control and well-being.

- Access to Resources: Providing access to hearing aids, assistive listening devices, and communication training helps individuals manage their hearing loss more effectively and participate more fully in social and professional activities.

- Psychological Impact: Empowerment is linked to reduced stigma and improved self-esteem. Individuals who feel empowered are more likely to seek help and utilize available resources.

- Educational Interventions: Programs that educate individuals about hearing loss and coping strategies can overcome stigma and empower them to manage their condition proactively.

- Community and Support Networks: Strong social and support networks are crucial for empowerment, providing emotional support and practical advice, which can alleviate the isolation often associated with hearing loss.

Bennett et al. (2022) created a short version of the Empowerment Audiology Questionnaire (EmpAQ-5) that enables HCPs to assess empowerment or devise treatment plans and goals to improve empowerment in the person with hearing loss. Overall, their research underscores that empowering individuals with hearing loss involves a combination of personal agency, access to resources, and supportive environments – all facilitated by hearing care professionals.

Spread Joy Up to the Maximum

As Figure 2 illustrates, social isolation, fear of being rejected by others and withdrawal from social life are among the biggest consequences of the stigma associated with hearing loss. There is evidence, however, that hearing aids can overcome these ill-effects. In an on-line survey of 398 hearing aid wearers, Mothemela et al. (2023) showed that hearing aid wearers who know more people with hearing loss who use hearing aids were more likely to demonstrate improved hearing aid outcomes. In contrast, hearing aid wearers who knew more people with hearing loss not wearing aids were more likely to demonstrate poorer outcomes. These findings highlight the advantages of a larger social networks of persons owning hearing aids. It suggests that insights from firsthand experiences of others optimizes hearing aid use and reduces stigma.

Based on this result, HCPs would be wise to target treatment goals that involve promoting larger social networks. Along those lines, HCPs can help hearing aid wearers enlarge their social networks and reduce stigma by encouraging the joining of a local or virtual hearing loss support group, use of social media to engage with other hearing aid wearers, facilitate participation in community activities tailored to the interests of the hearing aid wearer, and encouragement of physical activities, hobbies and other social activities.

Conclusions – Don’t Mess with Mr. In-Between

Released in 1944 during some of the darkest days of World War II, Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer penned the classic tune, Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive. No other set of song lyrics captures the essence of addressing and overcoming the stigma of hearing loss.

If you wanna hear my story

Then settle back and just sit tight

While I start reviewing

The attitude of doing right

You gotta ac-cent-tchu-ate the positive

E-lim-i-nate the negative

And latch on to the affirmative

You got to spread joy up to the maximum

Bring gloom down to the minimum

Don't mess with Mister In-Between

By working together, innovating the form factor design and functionality of hearing aids and through better, more positive messaging, we can put a dent in the damaging effects that stigma has on the quality of life of middle-age and older adults. All of us play a role in accentuating the positive experiences of wearing hearing aids and eliminating the negative effects of stigma. By sticking to the principles set forth in this article, neither persons with hearing loss nor hearing care professionals will get caught in between perpetuating negative stereotypes of age-related hearing loss and positively affirming all the ways to overcome it.

References

Börsch-Supan, A. (2013). Myths, scientific evidence and economic policy in an aging world. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 1(2), 3-15.

Bos, B., Pryor, J., & Reeder, G. (2013). Stigma: Advances in theory and research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(3), 1-9.

Chasteen, A. L., Pichora-Fuller, M. K., Dupuis, K., Smith, S., & Singh, G. (2015). Do negative views of aging influence memory and auditory performance through self-perceived abilities? Psychology and Aging, 30(4), 881-893.

Chundu, S., Manchaiah, V., Han, W., Thammaiah, S., Ratinaud, P., & Allen, P. M. (2020). Social representation of "hearing loss" among people with hearing loss: An exploratory cross-cultural study. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 31(10), 725-739.

Chundu, S., Allen, P. M., Han, W., Ratinaud, P., Krishna, R., & Manchaiah, V. (2021). Social representation of hearing aids among people with hearing loss: An exploratory study. International Journal of Audiology, 60(12), 964-978.

da Silva, J. C., de Araujo, C. M., Lüders, D., Santos, R. S., Moreira de Lacerda, A. B., José, M. R., & Guarinello, A. C. (2023). The self-stigma of hearing loss in adults and older adults: A systematic review. Ear and Hearing, 44(6), 1301-1310.

David, D., Zoizner, G., & Werner, P. (2018). Self-stigma and age-related hearing loss: A qualitative study of stigma formation and dimensions. American Journal of Audiology, 27(1), 126-136.

Dillon, H., Day, J., Bant, S., & Munro, K. (2020). Adoption, use and non-use of hearing aids: A robust estimate based on Welsh national survey statistics. International Journal of Audiology, 59(8), 567-573.

Ekberg, K., & Hickson, L. (2023). To tell or not to tell? Exploring the social process of stigma for adults with hearing loss and their families: Introduction to the special issue. International Journal of Audiology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2023.229365

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on a spoiled identity. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Gotowiec, S., Larsson, J., Incerti, P., Young, T., Smeds, K., Wolters, F., Herrlin, P., & Ferguson, M. (2022). Understanding patient empowerment along the hearing health journey. International Journal of Audiology, 61(2), 148–158.

Hakvoort, C., & Burton, P. (2018). Increasing style, reducing stigma: The Styletto solution. Signia Backgrounder. Retrieved from www.signia-library.com.

Hétu, R. (1996). The stigma attached to hearing impairment. Scandinavian Audiology. Supplementum, 43, 12–24.

Humes, L. E. (2023). U.S. population data on hearing loss, trouble hearing, and hearing-device use in adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-12, 2015-16, and 2017-20. Trends in Hearing, 27.

Jones, E. E., Farina, A., Hastorf, A. H., Markus, H., Miller, D. T., & Scott, R. A. (1984). Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

Konrath, S., Fuhrel-Forbis, A., Lou, A., & Brown, S. (2012). Motives for volunteering are associated with mortality risk in older adults. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 31(1), 87–96.

Lelic, D., Parker, D., Herrlin, P., Wolters, F., & Smeds, K. (2024). Focusing on positive listening experiences improves hearing aid outcomes in experienced hearing aid users. International Journal of Audiology, 63(6), 420–430.

Levy, B. (2022). Breaking the age code: How your beliefs about aging determine how long and well you live. Vermillion: London.

Levy, B. R., Zonderman, A. B., Slade, M. D., & Ferrucci, L. (2012). Memory shaped by age stereotypes over time. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(4), 432–436.

Major, B., & O'Brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 393–421.

Marcoux, A., Dostaler, M., & Olesen, D. (2022). Signia Active: The beginning of an era of hearing without stigma. Canadian Audiologist, 9(1).

Marcoux, A., Taylor, B., & Olesen, D. (2023). The appeal of Signia’s innovative form factors and their role in the adoption of hearing aids. Canadian Audiologist, 10(6).

Mothemela, B., Manchaiah, V., Mahomed-Asmail, F., Graham, M., & Swanepoel, W. (2023). Factors associated with hearing aid outcomes including social networks, self-reported mental health, and service delivery models. American Journal of Audiology, 32(4), 823–831.

Nickbakht, M., Ekberg, K., Waite, M., Scarinci, N., Timmer, B., Meyer, C., & Hickson, L. (2024). The experience of stigma related to hearing loss and hearing aids: Perspectives of adults with hearing loss, their families, and hearing care professionals. International Journal of Audiology, 1–8. Advance online publication.

Rakita, L., Goy, H., & Singh, G. (2022). Descriptions of hearing aids influence the experience of listening to hearing aids. Ear and Hearing, 43(3), 785–793.

Ruusuvuori, J. E., Aaltonen, T., Koskela, I., Ranta, J., Lonka, E., Salmenlinna, I., & Laakso, M. (2021). Studies on stigma regarding hearing impairment and hearing aid use among adults of working age: A scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(3), 436–446.

Sartorius, N. (2007). Stigma and mental health. Lancet (London, England), 370(9590), 810–811.

Simpson, A. N., Matthews, L. J., Cassarly, C., & Dubno, J. R. (2019). Time from hearing aid candidacy to hearing aid adoption: A longitudinal cohort study. Ear and Hearing, 40(3), 468–476.

Southall, K., Gagné, J.-P., & Jennings, M. B. (2014). The sociological effects of hearing loss stigma: Applications to people with an acquired hearing loss. In J. Montano & J. B. Spitzer (Eds.), Advanced practice in adult audiologic rehabilitation: International perspective (2nd ed., pp. xx–xx). Plural Publishing.

Wallhagen, M. I. (2010). The stigma of hearing loss. The Gerontologist, 50(1), 66–75.

Williams, N. (2021). Addressing hearing loss stigma within the OTC context. Auditory Insight. Research Note, Q3. Retrieved from https://auditoryinsight.com/wpcontent/uploads/securepdfs/2021/11/Auditory_Insight_Stigma_AntiSmoking_Analog_Q3_2021.pdf

Wolters, F. J., Chibnik, L. B., Waziry, R., Anderson, R., Berr, C., Beiser, A., Bis, J. C., Blacker, D., Bos, D., Brayne, C., Dartigues, J. F., Darweesh, S. K. L., Davis-Plourde, K. L., de Wolf, F., Debette, S., Dufouil, C., Fornage, M., Goudsmit, J., Grasset, L., Gudnason, V., … Hofman, A. (2020). Twenty-seven-year time trends in dementia incidence in Europe and the United States: The Alzheimer Cohorts Consortium. Neurology, 95(5), e519–e531.

Citation

Taylor, B. & Jensen, N. (2024). Accentuating the positive: overcoming the complexities of stigma through thoughtful product design & more-effective person-centered communication. AudiologyOnline, Article 28940. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com