Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Define an acoustically challenging social situation and its impact on communication for older adults with hearing loss.

- Describe the effects of signal to noise ratio on effective communication for older adults with hearing loss.

- Describe the detrimental effects of noise levels in social situations for older individuals with hearing loss.

Introduction

Everyone is familiar with the difficulties associated with communicating in a noisy place like a restaurant, pub, or crowded party. Modern society is bursting with situations like these, where people gather to share a meal, enjoy a beverage, or socialize with family and friends.

When these spaces become crowded, the background noise level rises, and conversation becomes exceedingly difficult. In fact, many individuals probably agree the most difficult and frustrating listening conditions encountered in daily life occur when they are conversing with others in these acoustically challenging social situations.

Hearing care professionals, of course, are keenly aware of these situations, too. Not only do patients often complain to them about their communication ability in noisy places — even with properly fitted hearing aids, they, too, struggle with having conversations in noisy social situations. Walk into your favorite restaurant today and it is likely to be significantly noisier than it was a decade ago. It’s no joke that these difficult-listening places are more demanding than ever before.

Even though the noise reduction capabilities of modern hearing aids continue to improve, noise levels inside our favorite public places seem to rise even faster. It’s no wonder the chief improvement sought by more than 90% of current hearing aid owners is the improved ability to hear in noise (Manchaiah et al., 2021).

The objective of this tutorial is threefold:

- Provide clinicians with clear explanations they can share with patients on why communication in these acoustically challenging social situations is often fraught with difficulty, and advise on what patients can expect when they attempt to socialize in a typical noisy place

- Demonstrate proven strategies that can be used in the clinic to account for individual differences in patient performance in these situations

- Offer practical guidance on how to squeeze additional benefits from hearing aids in these noisy listening situations.

“I live and breathe, my friend, I live and breathe.” —Jerry Seinfeld, Season 7, Episode 2, “The Postponement”

Stop Me If You’ve Heard This Before

Everyone struggles from time to time with communication in background noise. Even young, healthy people with completely normal hearing find it incredibly challenging when trying to follow a conversation in high levels of noise. Hearing loss and age, of course, compound this problem. And as all clinicians know, just about every hearing aid wearer is vulnerable to communication breakdowns in background noise.

In fact, most hearing aid wearers judge the success of their devices by their ability to hear in these noisy situations — an assertion buoyed by numerous surveys, including 30-plus years of MarkeTrak data, as well as Hearing Tracker data collected from more than 15,000 adult hearing aid wearers.

An abundance of data shows a familiar trend: Communication in background noise is by far the biggest challenge associated with hearing loss. Similarly, as Manchaiah et al (2021) recently reported, the highest-rated hearing aid attribute is improved hearing in noise, besting other important wearer attributes such as hearing in quiet, reliability, phone use, and physical comfort.

It should come as no surprise that wearers judge their success with hearing aids through the lens of the devices’ performance in background noise. After all, some of the most important celebratory events occur in places where noise levels are high.

What hearing aid wearers judge to be most important, however, does not equate with frequency of occurrence. Field data collected from hearing aid wearers in everyday listening situations suggests individuals spend most of their time listening in relatively quiet places. For example, Sabin et al (2020), comparing a traditional best practice fitting protocol to a self-fit approach, found that less 20% of the time, listeners reported they were in noisy situations.

Wu and Bentler (2012) reported similar findings. In their study of 27 adult hearing aid wearers, the most common activity for older and younger participants was viewing media at home (TV), while the lowest percentage of time was spent in noisy environments.

In contrast, in a more recent study using the datalogging system of the hearing aid, a more objective measure of use time, Hayes (2021) found that wearers were in places of high noise less than 10% of the time. Crucially, Hayes (2021) also reported substantial individual variability across participants, as a smattering of wearers’ datalogging systems indicated they were in noisy places more than 50% of the time.

Although there is considerable individual variability, evidence from an array of sources (Keidser, 2009; Humes, et al., 2018; Wu, et al., 2018; Wagener, Hansen & Ludvigsen, 2008) indicates the typical hearing aid wearer spends less than one-quarter of their total listening time communicating or interacting with others in the presence of background noise. Yet, these acoustically challenging social situations are often reported by individuals with hearing loss to be the places where many of their most meaningful and enjoyable social interactions occur (Meister et al, 2020).

Noise Is Everywhere; Some Types Are More Challenging Than Others

When we refer to the challenges of hearing in background noise, we could be referring to several possibilities. We could be referring to the soft and often innocuous background noise of a kitchen appliance or the clattering air conditioner in the workplace. It could be the racket of aversive sounds like a dog barking or a car horn that, because they are now plainly audible for the first time in years, are now suddenly bothersome and annoying.

Background noise could even be the sound of other people laughing and talking — sounds that drown out the voices the listener wants to hear. The most significant obstacles can be the social situations in which multiple people are conversing at the same time, often when other noises or reverberations are occurring in the same space.

The difficulties associated with understanding speech in multiple-talker situations are associated with the term “cocktail party effect” (Bronkhurst, 2015). You don’t have to attend a literal cocktail party to be plagued by the cocktail party effect. Any place rich with sound, where multiple people are talking within earshot of the listener, can be challenging due to the combined effects of informational and energetic masking. (Energetic masking is mainly caused by the overall intensity of noise in the room making the speech signal of interest inaudible; informational masking is a byproduct of the listener’s inability to disentangle speech sounds of interest from similar-sounding speech.)

Although it is fair to conclude that the typical hearing aid wearer spends a few hours per day or week in noisy situations, it is likely an even smaller percentage of this time is spent in cocktail party-like noise. After all, we all know some of the most valued social occasions involve high levels of background noise.

Listening situations over the course of any given week could involve mixing with friends at a jazz brunch, mingling with neighbors at a crowded diner, or chatting with family at a raucous wedding reception — all situations that usually last an hour or two but are of immense social or emotional value for the hearing aid wearer. Hearing aid wearers ultimately judge the success of their fitting by how they perform in these high-leverage social situations.

Each of the scenarios described above comes with its own set of unique challenges, but they do share one common characteristic: They are acoustically challenging social situations of high value to the individual hearing aid wearer.

The focus of this tutorial is to examine individual differences in hearing aid wearer performance across acoustically challenging social situations — places such as restaurants, cafes, and pubs. These are listening situations where people want to participate in the conversation, laugh at the punch line of a good joke, or simply relax and enjoy their meal.

As this tutorial demonstrates, when the clinician focuses on the “3-Ps” of successful intervention, patients are more likely to experience optimal benefit in places where effective communication often falls short of expectations — and perhaps have a better experience than if they purchased over-the-counter hearing aids.

What Are the 3-Ps?

For clinicians to maximize individual benefit in acoustically challenging social situations, it is crucial to understand the three components of successful communication in them. Along with each “P,” here are the key questions addressed in each section of this tutorial.

- Place: What are the unique acoustic conditions that make communication challenging?

- Person: What accounts for individual differences in performance in these acoustically challenging places, and how can they be accounted for in the clinic?

- Product: Considering the acoustic challenges of the place and the individual differences of the person, how can clinicians squeeze the most benefits from the products (hearing aids and accessories) they fit?

The Place: What Are the Unique Acoustic Conditions of the Room That Make Communication So Challenging, and What Do Clinicians Need to Know About Them?

“These go to 11.” —Nigel Tufnel, explaining the power of his amps to a reporter in This Is Spinal Tap

Crowded restaurants and other similar social situations present some of the greatest listening challenges for everyone. Who hasn’t found themselves in a crowded social situation and been challenged to converse with someone over the din of loud background noise?

To quantify the magnitude of the problem, Pang et al., (2019) surveyed 50 adults with normal audiograms and self-reported difficulties hearing in background noise. Results of the survey, summarized in Table 1, indicate the most problematic background noises are the sounds of other people talking in the same room.

As Table 1 indicates, the most cited type of problematic background noise was “crowds” and “conversational noise.” This would include difficulty conversing in restaurants, cafes, and other social gatherings. Background music also can be an issue, including difficulty trying to converse in bars with live music or other places where music might be playing, and was cited as the second-most problematic background noise causing problems with communication.

Transport or machinery noise was tied with background music as the second-most cited challenging noise. Note also that a small number of responses related to poor room acoustics and reverberation — including those in classrooms and churches, as well as other places where hard surfaces like tiled ceilings and hardwood floors make conversation difficult. As this survey confirms, trying to converse with others in a crowded, noisy room presents the most consistent challenge for just about everyone.

Noise Type | Causing the Most Difficulty with Communication (%) |

Conversation/Crowd | 50.7% |

Music | 14.7% |

Transport/Machinery | 14.7% |

Unspecified | 10.9% |

Television | 4.5% |

Reverberation/Acoustics | 4.5% |

Table 1. Type of background noise causing listening difficulties in adults with normal audiograms and self-reported hearing difficulties in noise (Pang et al., 2019).

How Loud Is It?

During the height of the COVID 19 pandemic, when most indoor social gatherings were prohibited, it was easy to forget just how loud a busy restaurant, café, or crowded party could be. However, now that most pandemic restrictions have been lifted, we easily recall that the typical social gathering, especially during a popular time, is quite noisy.

We know, for example, that many of today’s most popular restaurants have replaced the plush, noise-free opulence of carpet and drapes with fashionable hardwood and polished metal minimalism. These design trends in modern restaurants have the unintended consequence of creating excessive noise levels, which tend to plague all listeners, especially older adults with hearing loss.

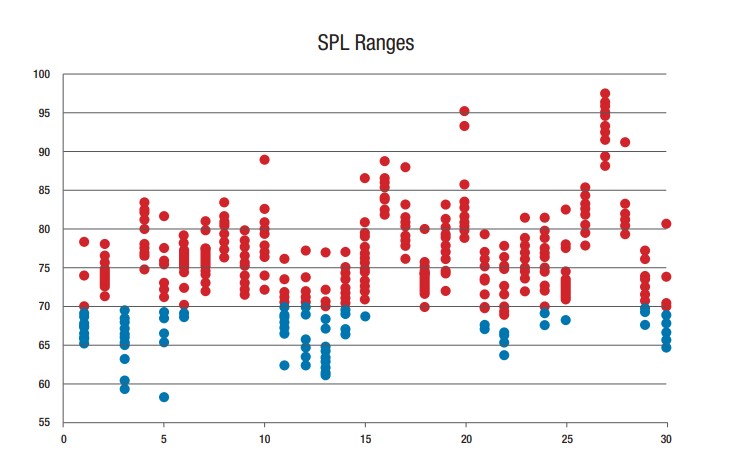

Restaurant owners might like the rapid rate of table turnover resulting from excessively loud dining experiences, but if you’re an older adult with hearing loss, the typical dining experience on a busy weekend can be maddening. In 2012, 30 popular restaurants in Orlando, Fla., had their sound levels measured over the course of about a month. Equipped with a sound level meter, researchers took 10 to 15 measures during either lunch or dinner — times when the restaurants were at least half full of diners. The results of these sound level measures are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Each dot represents an individual sound level meter recording during popular dining hours at 30 different restaurants in Orlando, Fla. Note the y-axis is the dBA scale. Adapted from Rusnock & McCauley Bush (2012).

The x-axis in Figure 1 represents the 30 restaurants, while the y-axis represents the A-weighted decibel level of the sound level meter (SLM) recordings. Note that for each restaurant, 10 to 15 recordings were made, with each recording being represented by a dot in Figure 1.

Although there is considerable variability in intensity levels across the 30 restaurants, approximately 75% of the recordings captured noise levels greater than 70 dBA – situations where talkers must raise the intensity level of their voice to be heard above the din of the background noise. In some cases, the noise level inside these restaurants was so intense that hearing protection was warranted. For example, restaurant 27 consistently generated intensity levels greater than 90 dBA, the equivalent of a diesel truck idling from 10 meters away.

If Orlando restaurants are representative of other busy indoor social gatherings, the following applies to the acoustic challenges faced by individuals with hearing loss in these types of social situations:

- Some places are so loud it warrants the use of hearing protection, especially if an individual spends an extended period of time there. Note that the SLM recordings in some of the restaurants exceeded the safety limits of 85 dBA, a level of exposure that can cause harm when averaged over an eight-hour day.

- Many restaurants have considerable variability in their noise levels during popular dining times. For example, restaurant 5 ranges from less than 60 dBA to over 80 dBA, suggesting that noise levels fluctuate, even inside the same establishment. Additionally, room acoustics can vary dramatically within the same restaurant. For example, being seated in the middle of a crowded, reverberant room is likely to result in a much higher SLM measurement than being seated in another part of the restaurant where there might be a sound-absorbing tapestry on the wall or a rug under the table.

- In about one-quarter of the measurements, the noise level is below 70 dBA, an intensity level low enough to enable talkers to converse without having to raise their vocal effort. However, at these lower noise levels it is quite possible that they remain bothersome even though they are probably not intense enough for the hearing aid to switch automatically from the omni to the directional mode. This suggests many patients might appreciate some type of manual override that enables them to switch into the directional mode whenever the noise level is bothersome, regardless of its intensity level.

- The average level of conversational speech in quiet surroundings is about 65 dB sound pressure level. As Figure 1 suggests, conditions are seldom quiet enough for the talker to speak at that intensity level. In most social gatherings, this data suggests talkers would have to raise the intensity level of their voices about 75% of the time

- Although a rare occurrence, it is possible to find restaurants and other similar public places where the noise levels are low enough to favor conversation. How individuals can identify these more tranquil areas using a crowdsourcing app with a global positioning system (GPS) is covered in Part 2.

Okay, It’s Loud, But Is It Bothersome?

Neitzel and Fligor (2019) remind us that an exposure of 85 dBA for 45 minutes has the same health risks as exposure to a continuous sound of 70 dBA for 24 hours. Figure 1 illustrates the high intensity levels experienced in crowded social gatherings. It is evidence that popular indoor dining establishments are often extraordinarily noisy and have the potential to cause hearing loss if the exposure is long enough and hearing protection is not properly worn. Although high levels of noise inside popular dining establishments have the potential to cause noise-induced hearing loss, perhaps the more likely consequence of noise exposure in these social situations is annoyance as well as other harmful effects such as hypertension, sleep disturbance and cognitive impairment. To address these questions, we turn to two other, more recent studies that suggest acoustically challenging social situations can be quite maddening.

In a randomized sample of 4,085 adults, Eichenwald, Murphy and Scinicariello (2022) found that 68.0% of respondents reported that a loud dining experience was somewhat or very annoying, while about that same percentage (64.8%) reported that it was very or somewhat likely they would avoid noisy restaurants. And perhaps more germane to hearing care professionals, adults over the age of 50 were significantly more likely to report that a loud restaurant was annoying than younger adults. Additionally, those aged 50 and older were two to three times more likely to report that they would avoid a noisy restaurant.

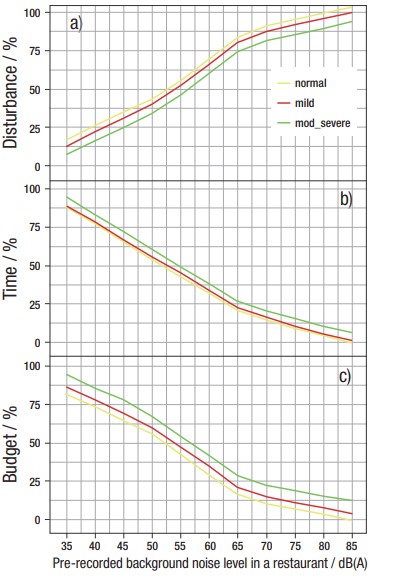

Bottalico, Piper and Legner (2022) surveyed 31 older adults on their reactions to background noise. Specifically, they divided these 31 older adults into three groups, striated by degree of hearing loss. The researchers evaluated the subjects’ perception of disturbance in communication and their willingness to spend time and money in a restaurant, as a function of the varying levels of background noise. The results indicated that background noise levels lower than 50 dBA enabled older adults to minimize their vocal effort and maximize their understanding of conversations, even for those with moderate to severe hearing loss. Of course, if the previously cited Orlando data in Figure 1 is characteristic of typical busy indoor social gatherings, it is probably impossible to find a public indoor dining area where the noise level is 50 dBA.

Figure 2. Relationship between the pre-recorded background noise level in a restaurant in dB(A) and self-reported communication disturbance (a), willingness to spend time (b), and willingness to spend money (c), for the three subgroups where the error bands indicate the standard error. Vertical dashed lines mark the change-points. Adapted from Bottalico, Piper and Legner (2022).

Figure 2 shows the relationship between background noise level (x-axis) and respondents’ self-rating along three variables:

- Disturbance in communication

- Willingness to spend time

- Willingness to spend money (all on the y-axis).

Across the three subgroups, we can draw the following conclusions when noise levels exceed 65 dBA:

- Disturbance: On a 0 to 100 scale, with 100 being a very high rate of disturbance, an average rating of 75% was achieved, suggesting that noise levels above 65 dBA are quite bothersome.

- Willingness to spend time: With 100% being “a long time,” participants were willing to spend 25% or less of their allotted time when noise exceeded this level.

- Willingness to spend money: Participants only were willing to spend 25% or less of their allotted dining budget when noise levels exceeded this level. Given the intensity levels of restaurants during popular dining times, not only is communication seriously compromised but older adults, regardless of degree of hearing, do not want to spend much time or money in them.

Given these findings, it is unsurprising that most older people are severely challenged and unwilling to spend time or money in situations where the noise level exceeds 65 dBA. Noise is not only burdensome with respect to communication, recent reports, summarized by Chasin (2022), indicate several harmful effects associated with seemingly innocuous levels of noise. These harmful non-auditory effects include cardiovascular, cognitive and sleep disturbances. Although these long-term health effects associated with noise must be a consideration to hearing care professionals, our attention now turns to how hearing aid wearers communicate in noisy social situations. Even though noise levels can be harmful and burdensome, these are essential places where patients need to be encouraged to communicate because they lessen the effects of loneliness, withdrawal and social isolation – common characteristics of untreated hearing loss

It’s All About the SNR

Listeners might be frustrated, annoyed, and unwilling to spend time or money in acoustically challenging social situations, but can they carry on a conversation? To address questions of performance, we turn to the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Just how severely challenged listeners with hearing loss are in these places is largely a function of the overall intensity level of the noise and the intensity of level of the talker(s) of interest.

Alone, neither the intensity level of the talker nor the noise level of the listening situation is all that useful in determining the magnitude of the communication challenge. A more useful metric is the SNR of the listening situation. Positive SNR values indicate the speech is louder than the noise, whereas negative SNRs indicate the noise is louder than the speech.

For individuals with normal hearing, research suggests the SNR must be +6 dB for adequate communication (Moore, 1986). Although everyone struggles to communicate in SNRs that are worse than +5 dB, individuals with hearing loss, by and large, require a significantly more favorable SNR to achieve the same levels of communication in background noise compared to those with normal hearing.

Additionally, it is critical to know that the talker increases their vocal effort as the noise level increases — a phenomenon known as the Lombard Effect. As illustrated in Table 2, the more intense the background noise, the less favorable the SNR, despite the increase in vocal effort. As noise levels exceed 55dBA and the SNR approaches 0, communication becomes more difficult.

Now, consider that the average noise level in a bar or restaurant approaches 75 dBA (Figure 1). This equates to a -2 dB SNR — a listening situation that is challenging for everyone, especially those with hearing loss, and one that all of us are likely to encounter when we step into a busy restaurant, café, or pub on a Friday night.

If the background noise is … | Speech is ... | The SNR will be … |

45 dBA | 55 dBA | +10 dB |

55dBA | 61dBA | +6 dB |

65 dBA | 67dBA | +2 dB |

75dBA | 73dBA | -2dB |

Table 2. SNR as a Function of Background Noise. Table adapted from Ricketts, Mueller and Bentler (2019).

The SNR values listed in Table 2 are based on data collected in a landmark study (Pearsons et al., 1977) using classroom teachers who were likely to have strong voices. Thus, for older adults who were more likely to have conversational partners with voices that didn’t project as well as those used in the data from Table 2, the SNR values they experienced in the real world are probably more adverse (a negative SNR) than those illustrated here.

Noise is a significant barrier to the enjoyment of noisy social situations for everyone, especially for older adults with hearing loss. All told, because of the effects of crowd noise and reverberation, the overall noise level of acoustically challenging social situations tends to severely limit communication for everyone. However, older adults with hearing loss and communication partners with weaker voices are particularly susceptible to problems in these areas. Although it would be tempting to simply tell all older adults with hearing loss to avoid these places, because hearing loss is associated with a higher risk for loneliness and social isolation, especially older adults, and difficult listening environments can lead to withdrawal from social situations, it is imperative that adults with hearing loss are provided effective strategies for communicating in these situations. That is, clinicians can lessen the ill effects of cocktail party noise through clear and effective counseling and education.

What Patients Need to Know About the First “P” — Place

1. Today’s modern restaurants and other similar social venues are extremely noisy. During busy times, the noise levels are high enough that everyone is challenged by them. For some savvy patients who use a smartphone, they can be encouraged to download a sound level meter app (e.g., NIOSH SLM). Clinicians can teach them to measure room noise with the SLM app and identify places with the lowest noise levels. Although relatively scarce during popular socializing times, areas with noise levels under 65 dBA offer the best chance of easier communication in noise.

Although there is considerable variability in the overall noise level, during popular dining times, patients should expect the signal-to-noise ratio of the room to be adverse, likely 0 dB SNR or worse. To improve the SNR, encourage companions to sit directly in front of the patient at no more than 3 feet whenever possible, and project their voices to the best of their ability. Even a modest increase in the intensity of the talker of interest can have a beneficial effect on the overall SNR

2. Given the large variations in noise within the same restaurant, patients need to ask to be seated, whenever possible, in the area with the lowest noise levels. They also need to know that asking the host for preferential seating may not be enough, since boisterous laughter from a nearby table can lower the overall SNR and is a random occurrence that cannot be avoided. Further, patients need to be reminded that multiple factors can affect ambient sound levels in restaurants, including room shape and materials, background music, seating style and the number of people in the room. Interior and architectural designs, such as open kitchens, hard surfaces, and an absence of upholstered chairs, tablecloths, carpeting, draperies, plants, or sound-absorbent paneling, also influence noise levels. To compensate for higher noise levels, patients should be reminded of the innate effects of the Lombard effect – the intuitive ability of talkers to raise the intensity level of their voices. However, they also need to be reminded that older talkers tend to talk at a lower intensity level which limits the effectiveness of the Lombard effect with many of their common conversational partners.

3. Finally, all patients need to be reminded of two overarching principles that improve the probability of successful communication in any acoustically challenging situation. Part of any holistic approach, regardless of patient age, degree of hearing loss or cognitive ability, must include guidance on these two principles:

- Be Assertive: Ask for clarification, ask for talkers to speak up and clearly enunciate, ask the talker to move closer to you, and ask to be seated in the quietest part of the room.

- Be Aware: Avoid the noisiest parts of the room, get adequate rest prior to a busy social gathering to minimize problems with fatigue, and rely on lip reading, facial expressions, and knowledge of linguistic context to fill in the blanks of conversation masked by background noise and reverberation. Also learn how to use any special functions on hearing aids (remote microphone, Bluetooth-enabled streaming, dedicated program for noise, etc.) to optimize performance.

Now that we know we can expect an adverse SNR of 0 dB or worse inside many indoor social gathering during popular times, Part 2 focuses on the person and what clinicians can do to better understand individual performance differences in these popular, socially valuable, and often adverse listening situations.

References

Bottalico, P., Piper, R. N., & Legner, B. (2022). Lombard effect, intelligibility, ambient noise, and willingness to spend time and money in a restaurant amongst older adults. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 6549.

Bronkhorst, A. W. (2015). The cocktail-party problem revisited: early processing and selection of multi-talker speech. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics, 77(5), 1465–1487.

Brungart, D. S. (2001). Informational and energetic masking effects in the perception of two simultaneous talkers. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 109(3), 1101–1109.

Chasin, M. (2022) Non-auditory effects of environmental noise. Hearing Review, 29(8), 8–17.

Eichwald, J., Murphy, W., & Scinicariello, F. (2022) Study Shows Noisy Restaurants Pose Health Risks. The Hearing Journal, 75(1), 8–12.

Hayes, D. (2021). Environmental Classification in Hearing Aids. Seminars in Hearing, 42(3), 186–205.

Humes, L. E., Rogers, S. E., Main, A. K., & Kinney, D. L. (2018). The Acoustic Environments in Which Older Adults Wear Their Hearing Aids: Insights From Datalogging Sound Environment Classification. American journal of audiology, 27(4), 594–603.

Keidser, G. (2009). Many factors involved in optimizing environmentally adaptive hearing aids. The Hearing Journal, 62(1), 26–28.

Manchaiah, V., Picou, E. M., Bailey, A., & Rodrigo, H. (2021). Consumer Ratings of the Most Desirable Hearing Aid Attributes. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 32(8), 537–546.

Meister, H., Wenzel, F., Gehlen, A. K., Kessler, J., & Walger, M. (2020). Static and dynamic cocktail party listening in younger and older adults. Hearing Research, 395, 108020.

Moore, B. C. (1989). An introduction to the psychology of hearing. London, UK: Academic Press.

Neitzel, R. L., & Fligor, B. J. (2019). Risk of noise-induced hearing loss due to recreational sound: Review and recommendations. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 146(5), 3911.

Pang, J., Beach, E. F., Gilliver, M., & Yeend, I. (2019). Adults who report difficulty hearing speech in noise: an exploration of experiences, impacts and coping strategies. International Journal of Audiology, 58(12), 851–860.

Pearsons, K., Bennett, R., & Fidell, S. (1977). Speech Levels in Various Noise Environments. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Environmental Health Effects Research Series.

Rusnock, C., & McCauley Bush, P. (2012). Case Study: An Evaluation of Restaurant Noise Levels and Contributing Factors. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 9(6), D108–D113.

Sabin, A. T., Van Tasell, D. J., Rabinowitz, B., & Dhar, S. (2020). Validation of a Self-Fitting Method for Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids. Trends in Hearing. 24.

Wagener, K. C., Hansen, M., & Ludvigsen, C. (2008). Recording and classification of the acoustic environment of hearing aid users. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 19(4), 348–370.

Wu, Y. H., Stangl, E., Chipara, O., Hasan, S. S., Welhaven, A., & Oleson, J. (2018). Characteristics of Real-World Signal to Noise Ratios and Speech Listening Situations of Older Adults With Mild to Moderate Hearing Loss. Ear and hearing, 39(2), 293–304.

Citation

Taylor, B. & Jensen, N. (2022). Optimizing patient benefit in acoustically challenging social situations, part 1: place. AudiologyOnline, Article 28361. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com