The prevalence of hearing loss in older adults is high and on the rise, and despite technological advances, only a small proportion use hearing aids. According to data from the National Health And Nutritional Examination Surveys (NHANES), prevalence of hearing aid use is consistently low, ranging from 4.3% in individuals age 50-59 years to 22% among those over 80 years (Chien & Lin, 2012). Low adoption rates are attributable to a number of variables including financial considerations, stigma, psychosocial factors such as motivation level and availability of social support systems. Ironically, failure to offer an array of hearing health care intervention options targeted to patient readiness is a major factor contributing to low utilization rates (Laplante-Lévesque, Hickson, & Worrall, 2012a). Additional clinician-driven shortcomings accounting for low adoption rates include clinician communication style, failure to foster trusting relationships, and reluctance to engage in shared decision making, which is at the heart of patient-centric care.

Learning Objectives

The first objective of this tutorial is to review some of the pertinent literature on shared decision making and patient-centered care, and how it can be used to optimize the patient experience in general and increase hearing aid uptake levels in particular. The second objective of this tutorial is to provide audiologists with a working framework for implementing participatory care into their practices through use of decision aids. Designed to present medical evidence to patients in order to assist them in identifying screening and diagnostic testing, patient decision aids (PDAs) are important vehicles for maximizing patient participation (McCaffery, Holmes-Rovner, Smith, Rovner, Nutbeam, Clayman, et al., 2012). They are especially important as a patient’s presence at an initial consultation does not automatically imply that the individual is interested in purchasing hearing aids (Claesen & Pryce, 2012). Rather, patients may be seeking education about the range of options, reassurance, and/or support. By providing a full range of hearing health care intervention options using PDAs, patients are more likely to trust the provider and maintain control of the decision-making process – both germane to patient-centric care.

Relationships and Trust

There are two recent veins of clinical research that can help audiologists better understand the critical role of effective communication and how it can be leveraged in the practice of patient-centric care. At their core, both veins of research indicate that non-technical factors, such as empathy, active listening and the ability to maintain an effective dialogue with help seeking individuals are more critical to the long term success of patients, than is a more technologic focus .

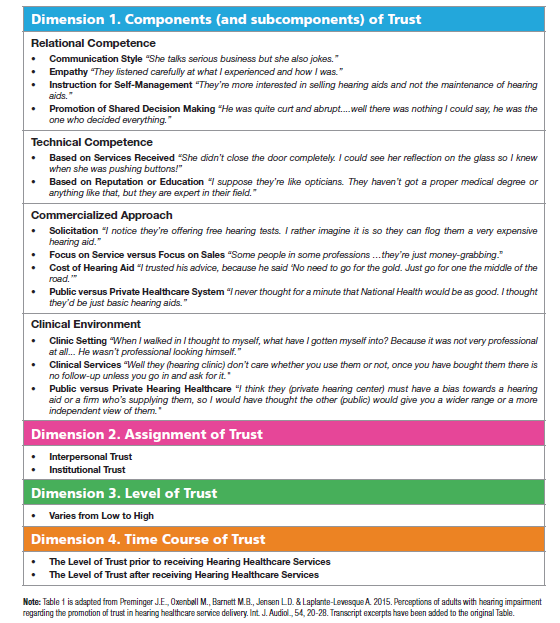

Trust appears to be the elixir of effective, long-term professional relationships. In other words, when clinicians focus their attention on gaining and improving their level of trust, they are likely to promote patient-centric care. Preminger and colleagues (2015) analyzed transcripts of face to face to better understand how trust influences the patient’s outlook toward care. In the earlier companion study (Laplante-Lévesque, Hickson, & Worrall, 2012b) trust was spontaneously discussed by 29 of the 34 participants during their interviews. Preminger et al. (2015) reread all of the transcripts of the viewpoints of the 29 participants, examining dialogue centered on issues of trust. After coding and organizing the themes they categorized the responses into four dimensions of trust as shown in Table 1. Quotes from the transcripts from the study are shown in Figure 1 to further elucidate the categories in Table 1.

Table 1. The four dimensions of trust. Reprinted from Preminger (2015) with permission of the Academy of Doctors of Audiology.

Preminger, et al. (2015) suggest that trust between the clinician and patient will be strengthened when the audiologist demonstrates the following set of skills:

- Good communication skills

- Empathy

- Enables shared-decision making

- Promotes self-management – e.g., teach them how use hearing aids properly

- Exhibits technical competence

The skills needed to promote and foster trust are valued by audiologists and patients alike. Laplante-Lévesque and colleagues (2013) conducted four focus groups with patients and audiologists. The objective of their focus groups was to gather information about the elements and meaning of an optimized hearing aid fitting from the perspective of both audiologists and patients. In general, patients and audiologists shared the same thoughts about the importance of patient-centered communication, as each group highlighted the importance of patient access to information. Their results indicated that audiologists were aware of the need to provide the appropriate type of information to optimize benefits without overwhelming patients with too much information, and that the information had to be conveyed in the right tone.

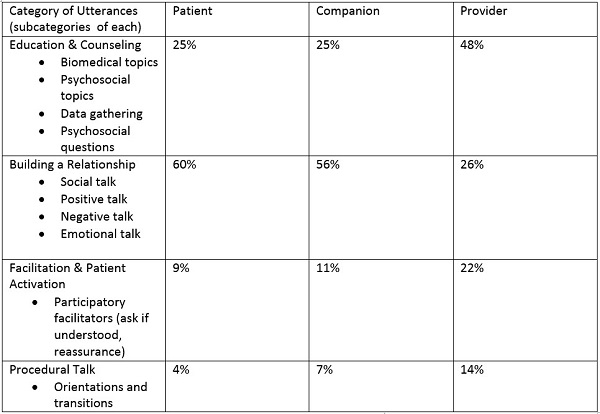

An audiologist’s knowledge of effective communication skills, however, does not translate in to the application of these skills in the clinic. Grenness, et al. (2015) examined the nature of audiologist-patient communication during the initial consultation process. A total of 62 consultations were filmed and analyzed. Clinician patient communication styles were placed into one of four categories: education & counseling, data gathering, relationship building and facilitation & patient activation. Forty-eight percent of the audiologists utterances were classified as education and counseling in nature. Within this category, 83% of education and counseling utterances were biomedical in content, which included an explanation of the audiogram and the possible cause of the hearing loss. Despite the desire on the part of audiologists to engage in patient-centered care, their results indicated that the patient-provider dialogue was dominated by the audiologist, as more than 75% of the educational and counseling time revolved around discussion of hearing aids with rapid movement from talk about test results to discussion of hearing aid options.

Table 2 shows a breakdown of the type of utterances used by audiologists, patients and their companions as coded by Grenness, et al. (2015). Patients and companions spent the largest percentage of their utterances on building relationships with “positive talk” or agreement utterances comprising the largest subcategory within that particular category. Nearly 50% of utterances by audiologists were categorized as education, and counseling was focused on technical matters, primarily hearing aids. A small amount of time was devoted to explaining the diagnosis or discussion of rehabilitation options. Although audiologists appear to recognize the need for patient-centric communication, Grenness, et al. (2015) clearly demonstrate a communication breakdown with many missed opportunities during the initial consultation for the clinician to better understand the needs of the patient.

Table 2. Percentage of time of four categories of utterances with subcategories listed for each for the three parties involved in an initial consultation (Adapted from Grenness, et al., 2015). Note the disconnect between the patient’s focus on relationship building and the providers focus on more technical aspects of the appointment’s dialogue.

Behavior Change

Given the importance of trust and communication, it is imperative audiologists move from the medical model, in which the focus is on the audiogram and hearing aid technology, to a biopsychosocial model with needs of the individual front and center. Moving to more patient-centric delivery model starts with audiologists getting more actively involved in patient behavior change. Focusing more on the person rather than the hearing loss, this process starts with gaining a better understanding of the patient’s role in the help-seeking and rehabilitation processes, including application of the stages of change model. The transtheoretical stages-of-change model is comprised of the following stages: pre-contemplation (“condition doesn’t exist”) contemplation (“condition may exist”), preparation (“condition exists, but not necessarily ready”) and action (“condition exists, ready to change”). When patients present to a clinic seeking help, they are likely to be in one of these four stages of change. Shared decision-making enables the audiologist to understand the patient’s stage of change, which will help guide them through the process of self-awareness and eventual behavior change.

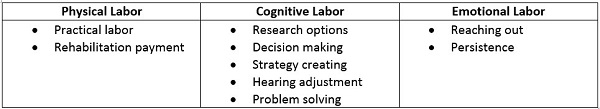

In order to better understand help-seeking behavior of patients, Knudsen, et al. (2013) conducted interviews with 34 hearing impaired participants in four countries. These efforts by patients to participate in help-seeking and care delivery were termed “client labor” by the researchers. After analyzing the 34 participant interviews, three overarching types of client labor were ascertained (Table 3).

Table 3. Three overarching types of client labor with individual subcategories of each according to Knudsen, et al. (2013).

Client Labor Themes

Emotional Labor

Let’s take a closer look at the three overarching client labor themes. Emotional labor is probably best described as the patient’s feelings and attitudes invested into seeking help and attempting to solve communication problems associated with their hearing loss. According to Knudsen, et al. (2013) the initial moments of seeking help (reaching out) and the long-term follow-up (persistence) often associated with committing to a rehabilitation plan comprise the key subcategories of emotional labor.

Cognitive Labor

Cognitive labor is comprised of five subcategories and can be summarized as the thought put into achieving success with rehabilitation options and goals. These five subcategories shown in the center of Table 3 require some degree of reasoning and logic on the part of the patient some time during the process of seeking help and receiving care. The components of cognitive labor are listed in the order (from top to bottom) of how they are likely to be encountered by a patient, seeking help for the first time.

Physical Labor

The final aspect of client labor uncovered by Knudsen, et al. (2013) was physical labor. This aspect of client labor requires some type of physical or monetary effort. For example, patients are expected to insert & remove their hearing aids properly, and make an effort to physically get themselves to the clinic for appointments. The act of paying for rehabilitation also requires physical effort, as many participants in the interviews described their ability to pay as work.

These nine aspects of client interaction highlight the significant degree of effort involved in the process of obtaining care and support. Additionally, they serve to remind us of how challenging it can be to meet the holistic needs of our patients, as comprehensive patient-centric care lies far beyond the walls of the test booth and the hearing aid specification sheets. Taken as a whole, the three types of client labor provide us with a descriptive of how individuals with hearing loss perceive themselves and their role as participants in the rehabilitation process.

The insights from this client labor study provide audiologists with a roadmap for targeting specific areas on which to focus their efforts (Knudsen, Nielsen, Kramer, Jones, & Laplante-Lévesque, 2013). Audiologists are encouraged to explore patient concerns about emotional labor. By providing insights on communication strategies, problem solving ability and worthwhile choices with respect to rehabilitation options, audiologists would be well positioned to lessen the workload associated with cognitive labor. Lastly, by acknowledging patients spend precious time and money on hearing rehabilitation, audiologists can collaboratively explore alternatives that make rehabilitation more physically assessable and affordable.

Patient-Centric Communication: Self-Reports and Scaling Questions

In order to optimize patient-centered care, audiologists must find ways to address the client labor issues listed above. This starts with the implementation of communication strategies that build trust and foster patient-centered care. Poost-Faroosh, et al. (2015) evaluated the quality of the professional relationship by comparing patient and clinician ratings of the importance of several factors that contribute to effective communication. Interview data were collected and placed into one of eight categories that may influence hearing aid purchasing decisions. Much like other patient-centered models of care used in other realms of healthcare, Poost-Faroosh, et al. (2015) determined that the following five components of patient-centered care are relevant to the delivery of audiology services:

- Patient comfort

- Patient motivation and readiness

- Acknowledge and understand the patient as an individual

- Provision of useful and actionable information

- Shared decision making

Interestingly, three of these concepts (understanding and acknowledging the patient as an individual, conveying information and shared decision-making), were rated as more important by patients than by clinicians. Let’s examine each of these and their interconnectedness as they relates to patient-centered care. Ensuring patient comfort relates to both the physical and psychological components of the interaction. In addition to providing a physically comfortable and inviting space, ensuring patient comfort in terms of the audiologist’s ability to engender trust and putting the patient in a peaceful state of mind is critical. See Table 1 for a review of some of the main drivers of trust.

A second aspect of patient-centric care involves patient motivation and readiness. Taking the time to evaluate motivation and stages of readiness contributes to the decision making process. For example, by using a scaling question such as, “On a scale of 1 to 10 with 1 being not ready at all and 10 being completely ready right now, how would you rate your readiness to proceed with treatment options if we find one is needed?” Understanding stage of readiness can help guide the clinician regarding next steps in hearing health care intervention process. A self-report questionnaire such as the Characteristics of Amplification Tool (COAT) (Sandridge & Newman, 2006) is also useful for ascertaining the level of motivation a patient may have with respect to help seeking.

Acknowledging and understanding the patient as an individual is another driver of patient-centric care. According to Grenness, et al. (2014), the primary components of allowing a patient to experience individualized care are getting the patient actively involved in the consultation and ensuring the patient is thoroughly informed of their options. Active patient involvement entails the use of a communication needs assessment like the COSI or TELEGRAM, in which the patient is encouraged to self-rate their situational needs and difficulties on a 1 to 5 scale, as well as speech-in-noise testing, like the Quick SIN that measures speech understanding in listening situations most problematic for most patients. Additionally, a measure which uncovers the emotional consequences of hearing loss and social engagement should be considered, given the connection to healthy aging.

Ascertaining the patient’s stage of change is an integral part of patient-centric communication. Self-ratings and scaling questions (1-10 self-ratings by the patient) may help identify the patient’s stage of change as well as their willingness to try alternative intervention options, such as communication programs and directed audio devices). For example, a self-rating on the COSI or TELEGRAM of 2 or 3 (1 is no difficulty, 5 is great difficulty with communication) may suggest the patient is in the contemplation, rather than the action stage of change. Further work is needed to better understand a possible relationship between self-ratings and a specific stage of change. A self-rating equated with a lesser degree of handicap or willingness to get help may suggest that an intervention other than traditional hearing aids may be an appropriate course of action. The bottom line is that we must target our interventions to the patient’s stage of readiness, motivation level, et cetera.

Reinforcing the Message

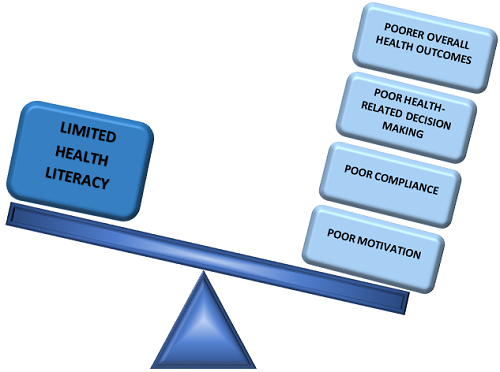

Another component of patient-centric care involves the delivery of information that is at the health literacy level of the patient. This process starts with the audiologist’s ability to use plain language to describe test results and possible treatment plans. Figure 1 displays the relevance of health literacy to hearing health care. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has created a health literacy toolkit and recommends that information is provided in three to five key points using plain language, rather than jargon or technical terms. The healthcare literacy toolkit is available at the AHRQ website.

Figure 1. Health literacy and patient outcomes.

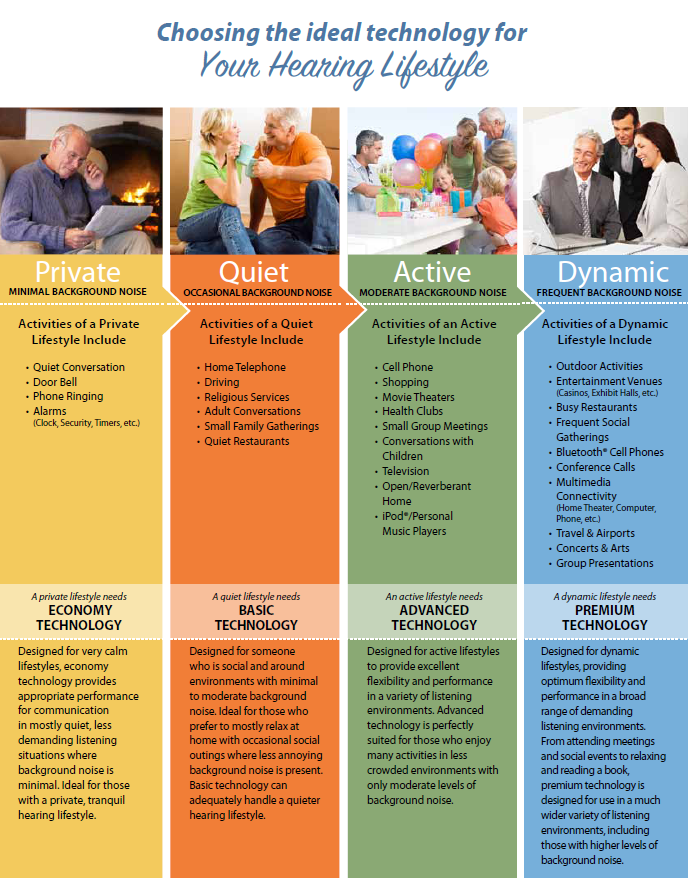

In addition to the use of plain, concrete language, audiologists can rely on visual aids that reinforce the message. Further, patients can be provided a hard copy of the visual aid or directed to a website where one can be downloaded after the consultation. Examples of this have been created by firms such as Fuel Medical and are shown in Figure 2. Other companies such as Counsel Ear even enable visual aids to be customizable for the patient. Table 4 lists the connection between health literacy and patient-centered care.

Table 4. Health literacy and patient centered care (IOM, 2005).

Finally, patient comprehension of hearing health information can be enhanced through the routine practice of the “teach back” method. Used in geriatric medicine, the “teach back” method is a step-by-step process, which includes asking the patient to explain a key point to ensure their comprehension, and if the patient did not understand, the clinician will know to reteach the information. It is a feedback loop of sorts (Gilligan & Weinstein, 2014.)

Figure 2. An example of a technology-focused visual aid intended to enhance communication. Figure used with permission of Fuel Medical, Portland, OR.

Shared Decision Making and Participatory Care

Participatory care is a model of healthcare in which patients take a more active role in the generation and implementation of treatment options. It requires a relatively high degree of healthcare literacy on the part of the patient (Gilligan & Weinstein, 2014) and involves the use of shared decision-making. Shared decision-making, which is an essential component of patient-centric care, is the process by which the patient and the audiologist exchange information about the scale and scope of the patient’s condition, express the preferences of intervention options and collaborate on the implementation and evaluation of a solution. Shared decision making and participatory care cannot be supported without adequate information provision (Poost-Faroosh, Jennings, & Cheesman, 2015), which includes the review of several possible treatment options

One of the most critical factors in the patient-professional relationship is the ability of the audiologist to advise patients on their treatment decisions. Recommendations from audiologists have been shown to be predictive of actions taken by the hearing-impaired patient. In other words, when the only treatment option offered to patients are hearing aids, a likely result is for patients to do nothing. For example, Laplante-Lévesque and researchers (2012) presented 153 adult participants with hearing loss several intervention options, including hearing aids, communication programs, and no intervention. Although all participants were considered hearing aid candidates, 39% of them chose no intervention and 18% completed a communication enhancement program. Thus, approximately one of five individuals with hearing loss will choose an alternative rehabilitation option when they have opted not to obtain hearing aids. Additionally, there is evidence that shows when patients have some semblance of choice in their treatment and management options, there are likely to be more willing participants in the consultation (Carson, 2015; Mead & Bower, 2000).

Decision Aids

Use of structured tools, such as PDA, is a novel approach to improving knowledge transfer and patient engagement in their treatment choices. Serving as a vehicle for patient participation, decision aids are tools that promote informed decisions on the part of the patient.

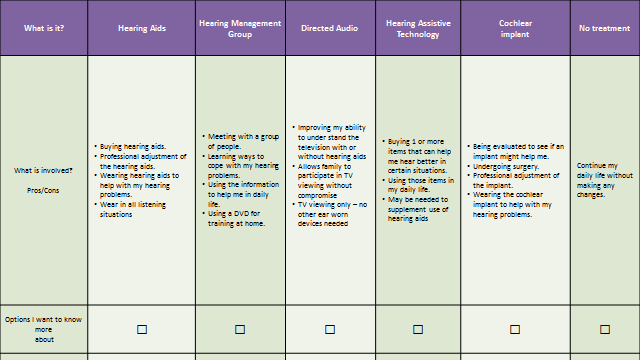

Given the importance of patient control in the decision making process, it is prudent for audiologists to include some type of decision aid in the consultation. The main purpose of a decision aid is to inform and educate patients of evidence in regard to treatment and management options. As Cox (2014) summarized, “a decision aid is a visual tool that helps organize and systemize a set of options. Audiologists can use it to facilitate a conversation with the patient to help him decide on a treatment plan.” In plain terms, it is a tool that allows the audiologist to guide patients through their intervention options.

A decision aid, like the one shown in Figure 3, can be used after the case history, communication needs assessment and hearing evaluation process. Or, it can be given to the patient to take home to assist in making a decision regarding the intervention option which will best meet their needs. Notice the decision aid shown in Figure 3 outlines six possible options for the patient. The role of the audiologist during this point of the consultation is to review these options in succinct detail, not to render an opinion of the best option for the patient. After guiding the patient through these options, the patient decides which of them he wants to discuss in more detail. Patients should be encouraged to discuss as many of the options as they are interested in learning more about. Although not all of the options listed on the decision aid are required to be offered by the audiologist (e.g., cochlear implants), the logical consequence of using a tool is that the audiologist’s practice is perceived by the patient as a complete hearing problem treatment center, rather than simply a hearing aid shop.

Using a decision aid (Figure 3) allows the audiologist to outline several alternatives to treatment. For example, after the audiological assessment, the audiologist can discuss the pros and cons of traditional hearing aids, hearing management groups, directed audio devices and no treatment. In this case, a hearing management group refers to group aural rehabilitation, where a patient attends several interactive group sessions with a companion. It also may include computer-based auditory training.

Figure 3. Example of a simple decision aid to be used with patients. Based on Laplante-Lévesque, et al. (2012) and Cox (2014).

One alternative with which some may be unfamiliar is directed audio devices. Directed audio uses ultrasonic energy to transmit an acoustic signal over a relatively long distance within a narrow beam for watching television. One recent clinical study indicates that a substantial number of hearing-impaired patients have a strong preference for directed audio technology for viewing television (Taylor, Hartenstein, & Grautterdaria, in press).

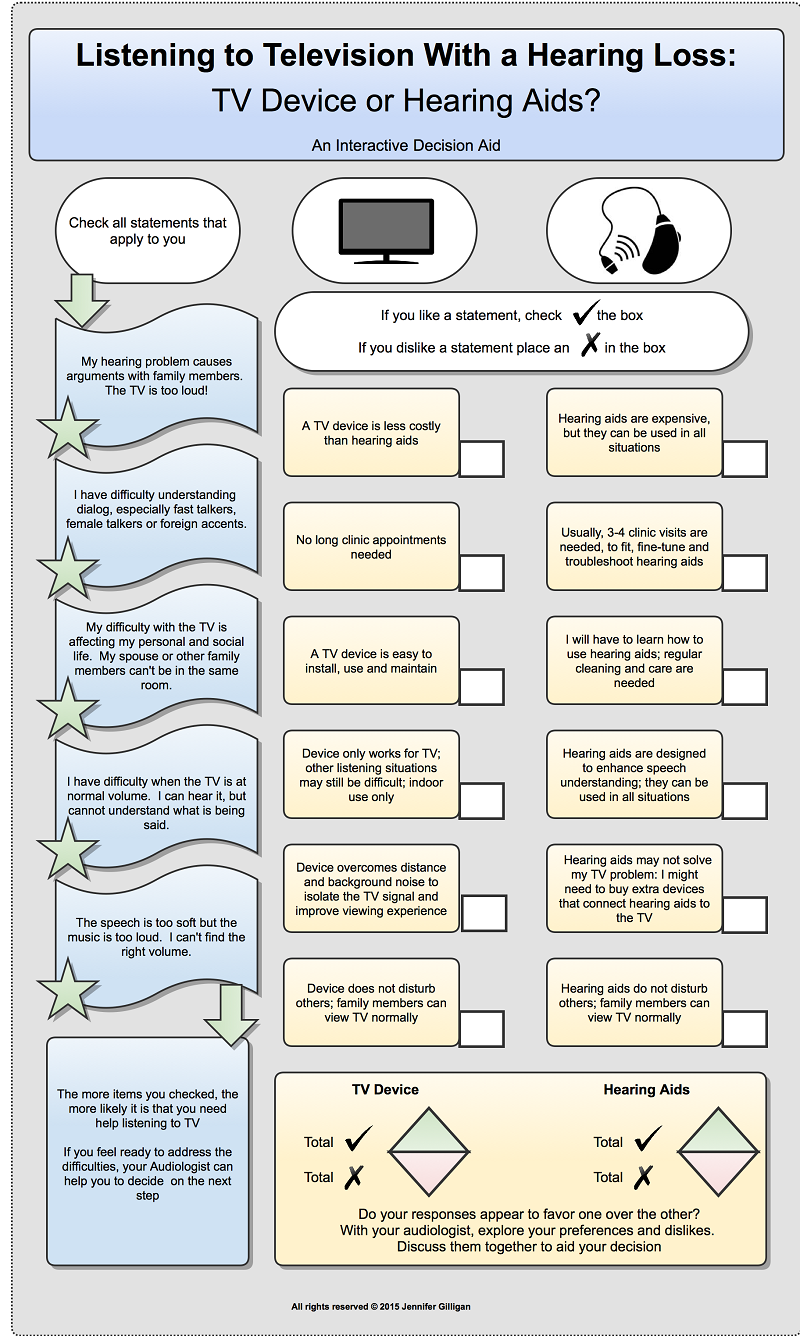

Patient decision aids can also help audiologists guide the patient through the decision-making process after several alternatives have been narrowed down to two. As the info-graphic in Figure 4 shows, the patient with the help of the audiologist has narrowed his choices to a hearing aid and directed audio. By answering the five yes/no questions on the right margin of the decision aid, the patient is likely to uncover a possible need for using a directed audio device with the TV. After help with the television has been documented as a priority, the next step is to compare the pros and cons of the directed audio device to traditional hearing aids. Guiding patients through the process of using the decision aid is likely to provide the patient with a deeper understanding of their options, which is one of the foundations of patient-centered care.

Figure 4. Comparison of directed audio to traditional hearing aids for television watching. Reprinted with permission of Jennifer Gilligan.

Decision aids, such as the examples shown in Figures 3 and 4, need to become a necessary component of patient-centered care. Patient decisions, however, are a thought, while uptake of a treatment option is a behavior. Audiologists must be tuned into the behavior of their patients. As Laplante-Lévesque, et al. (2012a) indicated, 23% of participants in their study did not partake in the intervention option to which they originally agreed. Audiologists play an essential role in monitoring behaviors with respect to patient uptake of their decisions and must be willing to offer the appropriate alternatives if needed. Monitoring uptake over a long period of time, say six months to over a year, requires vigilance as well as the ability to offer alternative intervention options.

Audiologists tend to believe that the hearing aid is the solution for all manner of hearing problems encountered by patients in their clinic. Historically, it is the only tool in our bag that reliably addresses the needs of patients with hearing loss. As recent research indicates, however, enlisting the help of an audiologist does not automatically mean patients are seeking help from hearing aids. Improving the daily living of patients requires tools such as decision aids and technology such as directed audio that will expand the appeal of audiology care to new heights. Patients must leave our offices with a deliverable targeted to their stage of readiness and the consequences of hearing impairment. This requires audiologists to expand their repertoire of treatment options and apply the principles of truly patient-centric care.

References

Carson, A. (2015). An interview with Arlene Carson. Retrieved from www.audiologypractices.org/the-spiral-of-decision-making-an-interview-with-professor-arlene-carsonon.

Chien, W., & Lin, F. (2012). Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172, 292-203. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1408

Claesen, E., & Pryce, H. (2012). An exploration of the perspective of help-seekers prescribed hearing aids. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 13(3), 279-284. doi: 10.1017/S1463423611000570

Cox, R. (2014). 20Q: Hearing aid provision and the challenge of change. Audiology Online, Article 12596. Retrieved from the Articles Archives at https://www.audiologyonline.com.

Gilligan, J., & Weinstein, B. E. (2014). Health literacy and patient-centered care in audiology: Implications for adult aural rehabilitation. The Journal of Communication Disorders, Deaf Studies & Hearing Aids, 2, 110. doi: 10.4172/2375-4427.1000110

Grenness, C., Hickson, L., Laplante-Lévesque, A., & Davidson, B. (2014). Patient-centered audiological rehabilitation: Perspective of older adults who own hearing aids. International Journal of Audiology, 53(S1), S68-S75. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.866280

Grenness, C., Hickson, L., Laplante-Lévesque, A. L., Meyer, C., & Davidson, B. (2015). The nature of communication throughout diagnosis and management planning in initial audiologic rehabilitation consultations. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 26, 36-50. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.26.1.5

Knudsen, L. V., Nielsen, C., Kramer, S. E., Jones, L., &, Laplante-Lévesque, A. (2013). Client labor: Adults with hearing impairment describing their participation in their hearing help-seeking and rehabilitation. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 24(3), 192-204. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.24.3.5

Laplante-Lévesque, A., Hickson, L., & Worrall, L. (2012a). What makes adults with hearing impairment take up hearing aids or communication programs and achieve successful outcomes? Ear and Hearing, 33(1), 79-93. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822c26dc

Laplante-Lévesque, A., Knudsen, L. V., Preminger, J. E., Jones, L., Nielsen, C., et al. (2012b). Hearing help-seeking and rehabilitation: Perspectives of adults with hearing impairment. International Journal of Audiology, 51(2), 93-102. doi:10.3109/14992027.2011.606284

Laplante-Lévesque, A., Jensen, L. D., Dawes, P. D., & Nielsen, C. (2013). Optimal hearing aid use: Focus groups with hearing aid clients and audiologists. Ear and Hearing, 34(2), 193-202. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31826a8ecd

McCaffery, K. J., Holmes-Rovner, M., Smith, S. K., Rovner, D., Nutbeam, D., Clayman, M. L., et al. (2012). Addressing health literacy in patient decision aids. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making,13(Suppl2), S10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S10

Mead, N., & Bower, P. (2000). Patient-centeredness: A conceptual framework and review of empirical literature. Social Science & Medicine 51(7), 1087-1110.

Poost-Faroosh, L., Jennings, M. B., & Cheesman, M. F. (2015). Comparisons of client and clinician views of the importance of factors in client-clinician interaction in hearing aid purchase decisions. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 26(3), 247-259. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.26.3.5

Preminger, J. E., Oxenbøll, M., Barnett, M. B., Jensen, L. D., & Laplante-Lévesque, A. (2015). Perceptions of adults with hearing impairment regarding the promotion of trust in hearing healthcare service delivery. International Journal of Audiology, 54(1), 20-28. doi:10.3109/14992027.2014.939776

Sandridge, S., & Newman, C. (2006, March). Improving the efficiency and accountability of the hearing aid selection process - Use of the COAT. AudiologyOnline, Article 995. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.

Taylor, B., Hartenstein, B., & Grautterdaria, S. (in press). Patient preference for a directed audio device. Hearing Review.

Cite this Content as:

Taylor, B., & Weinstein, B. (2015, July). Moving from poduct-centered to patient-centric care: expanding treatment options using decision aids. AudiologyOnline, Article 14473. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com