This article is an edited transcript of a live webinar. Please download the accompanying handout of the webinar slides, which contain data, graphs, links and supplemental material.

Learning Objectives

- Readers will be able to describe the methodology differences between MT9 and previous MarkeTrak surveys.

- Readers will be able to describe the potential changes in government policies toward amplification products and their implications for a practice.

- Readers will be able to describe the findings of MT9 and their implications for a practice.

HIA Mission and Objectives

Carole Rogin: The Hearing Industries Association, HIA, is comprised of the companies on whom you depend for the excellent technology for your patients with hearing loss. On behalf of all of the HIA members, thank you for your business.

As part of HIA, these companies, which you know as head‑to‑head competitors for your business, park their competitive issues at the door and come together to do three important things: Government relations and public affairs; to collect and disseminate sales statistics; and very importantly, to do market research that we hope will increase the numbers of people with hearing loss in America who benefit from our products and from your professional services.

In the area of market development, HIA supports the Better Hearing Institute. At the Better Hearing website, betterhearing.org, we share information about the consumer’s journey that we believe is valuable for you and your patients, including surveys, and results from interviews and focus groups. Today we're going to be talking about MarkeTrak, specifically MarkeTrak 9 (MT9), which was fielded in 2014 with the initial results released in 2015. This is a longitudinal survey that we have been doing the United States every 4‑6 years since 1984. The survey looks at the attitudes, perceptions, beliefs and actions of people with hearing loss, and the barriers that they tell us about with respect to hearing aid use.

HIA Public Affairs Objective

Before we delve into MarkeTrak, I want to briefly discuss HIA's public affairs objective, which is to raise the importance of hearing in the hierarchy of health issues. Everything that we do is designed to help people learn about their hearing losses and how to take action to treat them. We need to be careful what we wish for, as you will see when I review some recent developments.

NIDCD

In 2009, NIDCD, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communicative Disorders, developed a working group on what they called “accessible and affordable hearing health care for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss”. The intent of this initiative was to improve both accessibility and affordability.

They defined access to hearing care as confusing to the consumer, with ill-defined professional roles, competing financial interests, and multiple points of entry.

Affordability was defined by this working group as “undetermined” in terms of its definition. However, NIDCD noticed largely from MarkeTrak data, that 76% of non‑adopters of amplification mentioned cost as a barrier, although not the main barrier. Non-adopters also indicated they did not know what hearing aids cost.

In looking at these considerations, NIDCD took the assumption that both access and affordability needed to be improved.

Institute of Medicine (IOM)/National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine

In Washington, people come together around issues and opportunities, and there has been a lot of discussion among the hearing health communities. As a result, the Institute of Medicine (IOM), which is part of the National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine, decided to put a spotlight on hearing health care. The mission of the Institute of Medicine (IOM)/National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine is to help people in government and the private sector make informed decisions by providing evidence‑based information.

IOM initially holds a workshop, and the work product of their workshop is a compilation of papers presented by experts in the subject matter area. In January 2014, IOM held a workshop on Hearing Loss and Healthy Aging. Their report was issued on the effects of age‑related hearing loss on healthy aging. It is an excellent report you can find at betterhearing.org or via IOM.

Many of our organizations contributed funds to this first workshop because the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine as well as the IOM are private entities that rely on outside funding to do their work. We in the hearing community were excited that an important medical entity was looking at age‑related hearing loss. We were anxious to have, for the first time, an array of experts in areas outside our own come together to focus on our subject matter. In addition to the hearing health community, the January 2014 workshop included gerontologists, epidemiologists, cardiologists, and experts in virtually every co‑morbidity of hearing loss, coming together to look at hearing loss and aging.

IOM has a sequential process and in 2015, they moved on to their second stage of focus, which is a consensus study. Unlike a workshop, the consensus study results in a series of recommendations. The IOM held five meetings in 2015 and their report and recommendations will be available at the earliest, the summer of this year. We don't yet know what kinds of recommendations they will be making.

President's Council of Advisers on Science and Technology

Another entity that turned a powerful spotlight on hearing and healthy aging was the President's Council of Advisers on Science and Technology (PCAST). The PCAST consists of subject matter experts who are appointed by the President of the United States. These experts provide guidance on policy decisions in the areas of science and technology directly to the President of the United States. PCAST does its work largely by interviews, and they also had a few meetings during the past year. The result of their work is recommendations issued in what's called the PCAST Letter Report, which goes directly, in this case, to President Obama. That report is entitled, Aging America & Hearing Loss: Imperative of Improved Hearing Technologies.

I want to share the recommendations in the PCAST Letter Report that has already been sent to President Obama. Please consider these recommendations in the context of the impact on your patients and your practices.

PCAST made four specific recommendations in their letter report.

PCAST recommendation 1. The first recommendation was made directly to the US Food and Drug Administration, which regulates the manufacturer of hearing aids, patient labeling and the conditions for sale of hearing aids in the United States. PCAST recommended that the FDA create a new category of basic hearing aids. They described this category as nonsurgical, air conduction hearing aids for bilateral, gradual onset mild to moderate hearing loss.

To you, this may sound exactly like hearing aids today as we know them, however, PCAST directed the FDA to consider making this category available for over‑the‑counter sale. Further, there would be no requirement for consultation with a credentialed dispenser.

In addition, PCAST directed the FDA to make available over‑the‑counter (OTC) hearing tests, so that individuals may self‑evaluate, self‑fit and self‑monitor their use of this new category of hearing aids.

Finally, the FDA was directed by PCAST to exempt this new proposed category of hearing aids from quality manufacturing requirements. FDA regulation is designed to ensure both the safety and the efficacy of medical devices like hearing aids. These requirements include, but certainly are not limited to, the quality of the components that are used in the manufacturing of our hearing aids, the processes that are employed to manufacture those hearing aids, bio‑compatibility of the materials in the hearing aids, and repair requirements, just to name a few. This first recommendation by PCAST is designed to exempt this new category of hearing aids from all of those requirements.

PCAST recommendation 2. This recommendation also refers to manufacturing, labeling for sale but it relates more directly to personal sound amplification products (PSAPs). PSAPs, have been available in the United States for decades. They have not created a big market for themselves in the past because people who use them didn't find much benefit. But there has been an explosion in the numbers of companies around the world producing these sound amplifiers, especially over the past five to six years. The Consumer Electronics Association has also turned its attention to the fact that there are 78 million baby boomers in the United States, at least half of whom tell us through the Census and The National Health Interview Survey that their hearing is a problem, some or all of the time.

The second recommendation that PCAST has made to FDA is to ask FDA to withdraw what is called a guidance document regarding PSAPs. The document is available at betterhearing.org in its draft form. It has not yet been finalized, but it gives us indication of the way the FDA was thinking about PSAPs at the time it was written. FDA's current thinking in its draft guidance document for PSAPs is that PSAPs are not intended to be used by people with hearing loss. However, this PCAST recommendation is that the FDA withdraw this guidance document so that PSAPs can market themselves as appropriate for people with binaural, age related, mild to moderate presbycusis hearing loss.

PCAST recommendation 3. PCAST’s third and fourth recommendations are directed to the US Federal Trade Commission, the FTC. The third recommendation is that the FTC require hearing care professionals to provide customers, clients and patients, with their audiogram and what they refer to as a “programmable audio profile” at no additional cost and in a form that can be used by others. I have never heard the term “programmable audio profile” before, so I cannot provide further details on it.

Further, this recommendation stipulates that the audiogram and programmable audio profile cannot be conditioned on any agreement to buy any products or services such as hearing aids.

PCAST recommendation 4. The final recommendation is that the FTC should also define a process that would authorize hearing aid vendors to have the ability, at the request of the patient or the customer, to obtain patient's test results at no additional cost to the consumer.

As you consider these recommendations, I suggest you think about the potential impact of them on your clients and patients, as well as on your practices and your businesses.

Today we’ll provide you with current information about what people in the United States with hearing loss think about in terms of their hearing loss, and what they have done or will do in treating or addressing those hearing losses. The information that Dr. Harvey Abrams will present will be beneficial to thinking about new ways to talk to your patients and clients with hearing loss. At this time, I’ll turn it over to Dr. Abrams.

MarkeTrak 9

Dr. Harvey Abrams: Thank you, Carole. I’m going to first discuss the MarkeTrak 9 (MT9) survey process and how it differs from previous MarkeTrak surveys. I will describe high level findings, and then get into some of the details within the context of the patient journey. I hope you find this a meaningful approach for understanding the findings of MT9 and how they may have an impact for your own practice.

Methodology MarkeTrak 9 v. Previous MarkeTrak Surveys

The previous eight MarkeTrak surveys used what is called a National Family Opinion Mail Panel. This was a paper and pencil survey sent out through the U.S. Postal Service and answered and responded to using a paper and pencil method.

By contrast, the MT9 survey employed an online survey technique that allowed for more detailed and sophisticated data collection and analysis. Some of the unique features associated with MT9 include what is called a multisource sample. That means that in addition to sending the surveys to people who have participated in panels before, the survey was also sent out to people who had never engaged in these surveys.

Second, MT9 was online and it was done in two parts. Those who responded that they had hearing difficulty continued with the second part of the survey, including both people who said they owned hearing aids and people who reported hearing difficulty but did not own hearing aids.

Another feature was randomized sections so that we eliminated or minimized order bias effect, to the extent possible. There was also routing and skipping capabilities using sort of branching logic, which made the survey much more efficient. This means that questions were presented only if, in fact, previous questions were answered in a particular way.

In addition, we used a best practice approach including blinding, meaning that the respondents did not know that this particular survey was necessarily associated with hearing loss. They were told that it had to do with general health and that's how the survey was presented to them.

There was more rigor on question wording and there were weighting adjustments for MT9 that were similar to how the EuroTrak survey data was weighted. In this way we're able to make better comparisons and contrasts with the EuroTrak data. That is a brief review of this MT9 methodology and how it differed from previous MarkeTrak surveys.

MT9 Overall Findings

(Editor's note - if you haven't already done so, it is recommended you download the course handout to refer to the graphs and data that will be discussed throughout the rest of the article).

Hearing Difficulty and Hearing Aid Adoption

Now I’ll get into overall findings, starting with what percentage of the American population reports a hearing difficulty, as well what percentage of the American population owns at least one hearing aid.

The rates for hearing difficulty and hearing aid ownership are similar to what previous MarkeTrak surveys have told us. The rate of hearing difficulty is 10.6%, and hearing aid ownership is about 3.2%. So if you do the calculation, hearing aid adoption rate is about 30.2%. As expected, hearing aid ownership and hearing difficulty increase with age. They tend to be higher for men than for women. The vast majority of hearing aid owners wear their hearing aids bilaterally.

The hearing aid adoption rate of 30.2% is somewhat higher than was reported in previous MarkeTrak surveys; however, we need to be a little cautious because of the changes in the methodology between MT9 and previous surveys.

We are seeing a larger increase in hearing aid adoption, particularly among younger people, which is encouraging. The average age of first time hearing aid owners is also slightly lower, from 69 years in previous surveys to 63 years in MT9, which is also encouraging. Finally, there appears to be more first‑time users according to MT9.

There tends to be an increase in owners who report a mild to moderate loss from 60% in MarkeTrak 8 to 72% in MT9. Not surprisingly, adoption rates increase with severity of loss, with the exception of those with profound hearing loss.

While hearing aid adoption rate appears to be going up, there is still a disparity between those who report hearing difficulty and those who report owning hearing aids as a function of age. So the older the individual gets, if they report a hearing problem, the less likely they are to owning hearing aids. Here is an opportunity certainly for us to narrow this gap.

Hearing Aid Satisfaction

In terms of satisfaction rate for hearing aids, it is about 90% for those who got their hearing aids in the last year. Satisfaction score for all owners regardless of the age of hearing aids is about 81%. This too, is an increase compared to previous MarkeTrak surveys.

We found in MarkeTrak 9, that over half of the respondents have relatively new hearing aids. This will become important as you’ll see in some later data. Of those respondents who have had hearing aids in the past and now have a new hearing aid, almost 90% report that their current hearing aid is meeting or exceeding their expectations. Half of repeat purchasers feel like their current hearing aid is much better than their previous hearing aid. Again, these are very encouraging findings.

In terms of respondents who report never wearing their hearing aid, or what we sometimes refer to in audiology as hearing aids “in the drawer”, the rate is about 3%. This is quite a change from what we've seen in the past. Very often the number of 12 to 15% is often given as the percentage of hearing aids that are not worn. In the MT9 survey, about 87% report using their hearing aids at least weekly.

Hearing Care Professional Satisfaction

Now, let's move on to questions about hearing care professionals. What is the satisfaction level reported for hearing care professionals among hearing aid owners? Satisfaction rates for those who have seen a hearing care professional in the last four years are at about 95% for hearing aid owners and 87% for non-owners, respectively. Looking across all respondents, it is about 93% for hearing aid owners and 83% for nonowners. Certainly these are high percentages, which is great, but how do you explain that gap? Why is there a 10% difference between owners and nonowners? Is there something that we could be doing as professionals to improve that level of satisfaction and perhaps increase hearing aid utilization as a result?

The fact that nonowner satisfaction is not at the level of owners, may be due to the lack of motivation to purchase hearing aids among the nonowners. Again, this represents a challenge for us as professionals to find a way to narrow that gap.

Adoption Rates by Age and Nation

We looked at whether the hearing aid adoption rate is much higher in countries with national healthcare programs that cover hearing aids. In the U.S., among those 75 years of age and greater, the adoption rate was about 40%. In France, a country with national healthcare, it is about 39%. So in fact, the adoption rate in France is a little lower.

For those people ages 65 to 74 years, according to MT9 the adoption rate is 39% in the U.S., compared to 40% in the U.K. So again, MT9 doesn’t give us much evidence to support the idea that having national health care coverage of hearing aids is going to lead to a higher adoption rate, since the hearing aid adoption rate is not much higher in countries with such programs.

Tinnitus

Approximately 5.6% of all respondents reported tinnitus. Now, this may be lower than what you probably think. If you read the literature, probably in the neighborhood of 10% of your patients are likely to report tinnitus; however, the language in MarkeTrak 9 was specific. I think it referred to “bothersome tinnitus” or “bothersome ringing, buzzing, chirping” and so forth. I think the term "bothersome" differentiated those that had tinnitus from those that perceived tinnitus as being bothersome, and thus we saw bothersome tinnitus reported at 5.6%. Of those, about one‑half of 1% had a tinnitus device or some type of masker.

We looked, too, at the characteristics of the tinnitus as reported by the respondents. About 74% reported that it was bilateral and about 52% reported that it was constant. This may provide an opportunity for professionals who are not already providing tinnitus assessment and treatment services, to add another important component to your practice. By offering these services, you can address a problem that is fairly common among patients who come into your office.

PSAPs

Carole provided an overview of how the government perceives PSAPs, and how they want to encourage an increase in the accessibility of these devices. What percentage of those with hearing difficulties do you think currently own a PSAP?

In the survey, PSAP was defined as, “a device that amplifies sound that was not fit by a hearing care professional”. About 1% of the population reported having a PSAP based on that particular definition, and this equates to about 9.4% of those with a hearing difficulty.

This is the first time MarkeTrak addressed the issue of PSAPs and it was not that easy. Consumers often think of many categories of devices when they see the term “personal sound amplifier”. Very often we ask them for a specific brand, and they either didn't know their brand or they list a brand that is really not a PSAP. This shed some light and certainly informed us as to how difficult it is to define PSAP and more importantly, the confusion that exists in the marketplace regarding these devices. In future surveys, we will try to be even more precise to try and get an idea of what devices people are using.

We’re seeing an increase in the number of PSAPs in the marketplace. There are many websites where consumers can order them, Amazon provides devices through their marketplace, and many amplification apps are available through the Apple Store.

Physician Screening

The issue of hearing screening by the physician is an important one, as previous studies have shown it is a key to consumers taking action. Twenty-three percent of adults reported having a hearing screening in their latest physical exam. This is up from 15% in previous MarkeTrak surveys. In MT9, another 11% reported that hearing was at least mentioned.

There are plenty of screenings available as apps. As professionals, you may have mixed feelings about that. Online programs are going to be increasingly accessible for consumers. Most of those surveyed in MT9 who reported receiving hearing tests at their physical exam had a formal test using an audiometer in a sound booth, and a much smaller percentage used some online tool or an app on a smartphone. However, with the trend in healthcare towards self‑diagnosis, we will likely see an increase in the use of online hearing screenings. Consider how you in your practice can address this, and get these people into your practice. In some cases, online screening may not be accurate, and in other cases they may confirm a suspected hearing loss. How do we get these patients into our practices to take the next step? I don't think it is enough to say no, you shouldn't take an online screening. I would suggest you tell people that if they take an online screening, they can them come in to your practice to review the results, and receive a comprehensive exam.

MT9 Summary – High Level Findings

Again, from a high level, we can conclude from MT9 that hearing loss rates are fairly stable. This means that due to aging of the American population, there are 78 million people moving into the range of people who are going to need our services. How do we get them into our practices?

We know from MT9 that hearing aid purchase percentages are up. The adoption rate is up for a number of possible reasons, including quality of technology, satisfaction with the technology, satisfaction with the provider, increase in physician screening and we hope word‑of‑mouth. Physician screening rates are up and it is important because we know our patients want guidance from their primary care providers. We know, too, that with the current healthcare landscape the primary care physician is the gatekeeper. We then need to educate them in terms of the effects of hearing loss on psychosocial issues and co-morbidities. We need to help them to increase hearing screenings in their practices.

It’s gratifying to see that consumer satisfaction is up both with the hearing aids and with us as hearing care professionals. Everything is in place to continue to improve the experience for people with hearing difficulties.

Along the Patient Journey with MT9

Rather than review more data, I’m going to put the MarkeTrak 9 data in context of the patient journey.

This patient is probably typical of patients you have seen numerous times in your practice. John is a 68‑year‑old, married retiree. He's experiencing increasing problems hearing the TV, understanding his wife and he's beginning to wonder what should he do next. If John is like millions of other Americans with hearing loss, he's about to embark on an interesting and perhaps confusing and long journey. This journey begins before he even knows he has hearing loss, although people around him probably suspect that he does. We hope the journey ends with satisfactory resolution of his communication problems.

It turns out that MT9 can help inform us what decisions John makes, how he makes those decisions and what we can do to enable this journey. And, these findings can apply to the journey of those who come to see us and even those who have hearing difficulty and haven't yet come to see us.

Transtheoretical (Stages of Change) Model

John's journey can be described by what is called a Transtheoretical model, which is sometimes called a Stages of Change model. This was proposed by Prochaska and DiClemente in 1983 to describe behavior change among people seeking to stop smoking. It has been later adopted and used in areas such as substance abuse, obesity, other chronic health care conditions, and most recently, to audiological rehabilitation. This model understands that change is hard. Behavior change is hard. People proceed and progress and sometimes regress. The stages are: Pre-contemplation, Contemplation, Preparation, Action, Maintenance, and Relapse.

I’ll describe these stages in more detail in the context of John and his journey toward better hearing.

Stage 1 – Pre-contemplation

The first of these stages is called pre‑contemplation. John didn't wake up one morning and say, ‘I'm going to go get a hearing aid’. Perhaps he's experienced some hearing problems but maybe doesn't even acknowledge that it is his fault. He may be blaming others, thinking they don't speak clearly enough, or that they speak too fast, particularly people on TV. He may think that his wife is mumbling. You have heard these feelings expressed time and again by your patients.

Stage 2 – Contemplation

At some point, John begins to understand that perhaps hearing loss is his problem. He contemplates taking action. He's beginning to hear complaints among his friends and his family. He gets to see that others are not having the same level of difficulty that he is experiencing in the same situations. This then becomes the stage in which he's thinking of taking action, but before he actually takes action. It is the contemplation stage.

Whether or not John actually takes action can be described in another model called the Health Belief Model (Glanz, Rimer, & Lewis, 2002). This model explains that people do some internalizing of the perceived susceptibility, perceived severity of a condition, perceived barriers, as well as the perceived benefits to taking action. In John's case, he is thinking about his hearing loss or suspected hearing loss and how susceptible he is to having hearing problems. Maybe he knows that people his age tend to have these problems. Maybe his father had problems. He is beginning to understand the severity as he has to ask people to repeat what they say and it is becoming embarrassing. He is considering the benefits of taking action. Maybe those include being able to go to the movies again, and turning the TV volume down so his wife will stop complaining. There are also barriers. Maybe John doesn’t even know how to start along the path. He also understands that hearing aids cost quite a bit of money. Let’s look at what MT9 tells us about John's potential barriers.

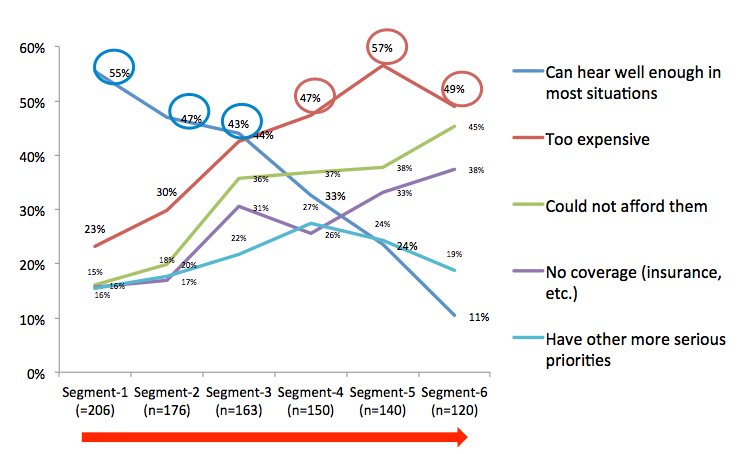

Barriers. We've heard about the issue of cost as a barrier, but it is not that simple. If we look at the x-axis of Figure 1, it starts with mild hearing loss on the left (segment 1) to more severe hearing loss on the right (segment 6). For those with mild to moderate hearing loss, the main barrier to hearing aid adoption is not cost but the perception that they already hear well enough in most situations.

Figure 1. John's potential barriers.

Among those with more severe hearing loss, the major barrier is, in fact, cost. So, barrier is a function of perceived severity of hearing loss and it is not always just a matter of cost.

It's also interesting to look at the time line in terms of when John takes action. It is about three and a half years between the time John notices he may have a problem and when he gets evaluated for the first time to confirm the hearing loss. It is about another one to one and a half years before he gets his first hearing aid. In our industry, it is commonly stated that it takes on average 10 years before an individual gets a hearing aid from the time they first notice a hearing problem, but that is not supported by the data in MT9.

Returning to John’s journey, after John has contemplated and considered the risks barriers and benefits, he is now ready to take action. But before he takes action he's going to prepare. What does preparation mean for John and the millions of others who take this journey?

Stage 3 – Preparation

Preparation means getting information. In the MT9 survey, 66% of all participants reported looking for information on the Internet. Among non‑hearing aid owners like John, about 72% look online for information.

Only 20% reported using print ads and direct mail to look for information. Toward the bottom of the list are information sessions or open houses that are sponsored by manufacturers (13%).

Now, in addition to where John is looking for information, we're interested in what kind of information John is seeking. At the top of the list is general information about hearing loss, followed by general information about hearing aids. Toward the bottom of this list is information on a particular brand of hearing aids. This may be informative to you in terms of how you design your marketing strategy. If everything is about the name of the manufacturer, you may be going about this the wrong way. Patients for the most part don't know the difference between Starkey, Widex and Oticon; they may know the names Beltone and Miracle Ear but that is probably about it. What they're most interested in is hearing loss, what causes it, and what it means to them personally. They want general information on hearing aids, particularly how hearing aids may help their individual situations.

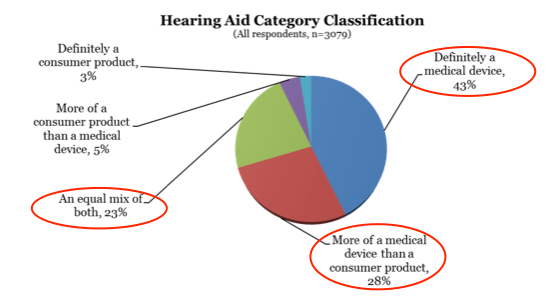

Also, it’s important to know if consumers think of a hearing aid more as a consumer electronic device or as a medical device. If they think they hearing aids are consumer electronic devices, they will be more likely to go online and buy a PSAP, or make the purchase in the same way that they may buy a new pair of earphones for their smartphone. MT9 tells us that two-thirds of consumers that were surveyed definitely think of hearing aids as a medical device or more of a medical device than a consumer product (Figure 2).

Figure 2. How do consumers think of hearing aids?

So generally speaking, individuals who report hearing difficulty think of hearing aids as a medical device.

Stage 4 – Action

Now John is ready to take action. Let’s look and see what kind of action he's going to take because we know he has options. We want to know what professional John is going to visit; he could visit primary care physician, an ENT physician, a hearing care professional, or some combination of those. According to MT9, the professional John is most likely to visit is the hearing care professional (31%), followed by his primary care physician (19%), and then an ear, nose and throat specialist (7%).

When we look at this in a little more detail, we see that 89% of hearing aid owners discuss their hearing problem with a hearing care professional. This is not surprising. But importantly, about 30% of the total number of people who report a hearing loss will discuss their hearing difficulty with their primary care provider.

Influence of primary care provider. Among hearing aid owners, 82% said that the primary care provider validated their hearing loss, either through a screening test, through some subjective questioning, or through the case history. Compare this to 9% of hearing aid owners who reported that their primary care physician said that their hearing loss was not bad enough for hearing aids. This underscores the influence of the primary care physician in validating the patient's concern about hearing loss, and the patient’s ultimate decision to purchase hearing aids.

Let's compare this to the nonowner; 55% of nonowners reported that their primary care physician validated their hearing loss concern and almost 30% reported that their primary care physician told them that their hearing loss was not bad enough for hearing aids.

Approximately 32% of hearing aid owners reported that their primary care physician directly recommended hearing aids. Again, the influence of the primary care physician cannot be underestimated.

Influence of ENT physician. Ninety-three percent of hearing aid owners reported that their ENT specialist confirmed their hearing loss. It's very possible that many of these ENT practices employed an audiologist.

Compare that to 8% of hearing aid owners who reported that the ENT physician advised that the hearing loss is not bad enough for hearing aids. Regarding nonowners, 69% who reported that the ENT physician confirmed their hearing loss and 30% of nonowners reported that the ENT physician told them that their hearing loss was not bad enough for hearing aids.

The ENT obviously is very influential over the patient’s decision to purchase hearing aids. Among hearing aid owners, 57% reported that the ENT physician recommended hearing aids. We don't know what the influence may have been of having an audiologist in the ENT practice.

Influence of hearing care professional. As you would expect, about 95% of hearing care professionals confirmed the existence of a hearing loss among those who ultimately purchased hearing aids, as compared to about 6% of hearing aid owners who reported that the hearing care professional told them that their hearing loss was not bad enough for hearing aids. Among nonowners, 72% reported that hearing care provider advised them in fact that they had a hearing loss compared to about 25% who reported that the hearing care provider told them their hearing loss was not bad enough for hearing aids.

Something worth investigating is the fact that 72% of nonowners reported that the hearing care provider advised them that they had a hearing loss; why didn't they ultimately purchase hearing aids?

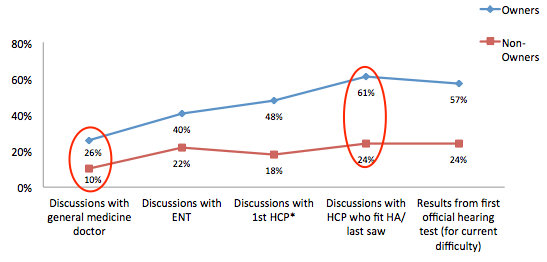

Again, we know that 87% of hearing aid owners reported that the hearing care professional recommended hearing aids. So how motivating is the health care provider across the journey? Figure 3 displays the data that looks at this question.

Figure 3. How motivating is the health care provider?

The primary care physician is not identified as being particularly motivating whereas the hearing care professional who initially fit the patient with hearing aids is considered more so. There is a gap between hearing aid owners and nonowners; the owners perceive the health care providers as being more motivating than the nonowners.

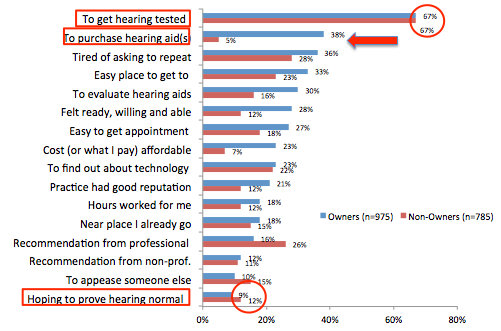

Reasons for choosing a hearing care professional. The data for this question is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Reasons for choosing a hearing care professional.

Both hearing aid owners and non-owners say that the primary reason to visit a hearing care professional is to get their hearing tested.

The next reason down this list is, in fact, to purchase hearing aids but there is a big difference between the hearing aid owners and the nonowners. Among the nonowners, purchasing a hearing aid doesn't score particularly high on their list of reasons for going to a hearing care professional; they just want to get their hearing checked.

Further down on this list is choosing a hearing care professional to prove that their hearing is normal. This is not a particularly compelling reason for the respondents of the MT9 survey to visit a hearing care professional.

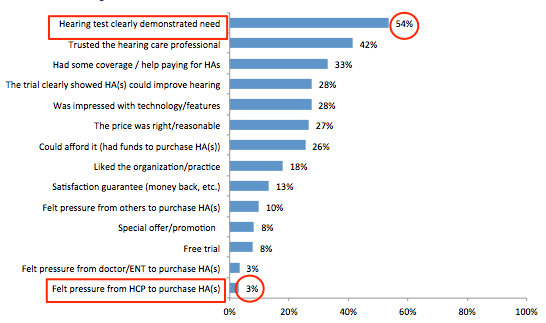

Reasons for purchasing at a particular clinic. Why will John purchase hearing aids at a particular clinic? The top reason for purchasing hearing aids at a particular clinic (Figure 5) is because the hearing test clearly demonstrated a need (54%).

Figure 5. Reasons for purchasing at a particular clinic.

So, it is important for consumers to receive an assessment that clearly demonstrates a need for hearing aids because people are still ambivalent about purchasing hearing aids. As a professional, you have been asked many times by your patients, “Do I need a hearing aid?” While you can give a yes or no answer, it would be a lot more effective if you provided an assessment that confirmed the need as perceived by your patient.

Toward the bottom of this list of reasons why people purchase hearing aids at a particular clinic is feeling pressure from the hearing care professional; clearly, that is not going to be a compelling reason.

Satisfaction with a hearing care provider. As I mentioned earlier, satisfaction with hearing care providers is quite high at over 90% among hearing aid owners. The key areas influencing satisfaction are the quality of service during the fitting, and quality of service after the purchase. At the bottom of the list is the selection of hearing aids carried. So the patient is not particularly impressed that you have hearing aids from a number of different manufacturers; it is the quality of care that you provide that matters.

Reasons for purchasing sooner. We’re interested in knowing what would motivate consumers to purchase sooner. The top reason (51%) is having insurance that would pay some/more of the cost. The number two response (36%) is getting a hearing test that makes it clear that they need a hearing aid. This is the second time we have seen the importance to an assessment that demonstrates a clear need for a hearing aid.

Least important on this list is having information on the latest technologies and how they improve hearing, and learning that people who wear hearing aids when their loss is milder are more successful.

The two top reasons that would motivate people to purchase hearing aids sooner are very important. On this topic, there is a great article by George Lindley (2015) entitled, They Say, “I can't hear in noise”, We say, “Say the word base”. How many professionals only test monosyllabic word recognition in quiet when patients say they cannot hear in noise? Simple speech tests in quiet are not meaningful to patients, and they are not particularly prognostic in terms of hearing aid benefit. Those types of tests should be abandoned at least for the purposes of selecting hearing aids and demonstrating need for hearing aids with patients.

Stage 5 – Maintenance

Let's assume that John is delighted with your care. He purchases hearing aids, and the next stage along this journey is the maintenance stage. It is not enough now that he has hearing aids. How is he going to maintain them, use them, and get the value and benefits that are associated with amplification?

First, John needs to have hearing aids that he perceives as being satisfactory. The data show that the newer the hearing aid, the higher the level of satisfaction. Over 90% of those surveyed reported satisfaction with hearing aids that were less than a year of age.

Over 85% report that their newer hearing aids were at least somewhat better than their previous hearing aids.

What are the factors that increase in importance for those who have worn hearing aids before? Half of repeat purchasers feel their current hearing aid is much better than their first because the perceived quality of the product is better, and because they feel the hearing care professional did a better job. They're now willing to use their new hearing aid more hours during the day and they have a better sense of what they need, including premium sound quality, reduced feedback, and ease of use. As professionals, it is typical that we find first time users are most concerned with cosmetics. Those repeat wearers who are coming in for a new set are most concerned with performance.

Key factors that influence satisfaction are ease of use and product quality; at the bottom of the list is value v. price, and cost. If you dig deeper into factors that influence satisfaction you find that wireless features are very important to people’s perception and satisfaction with hearing aids.

Satisfaction as a function of specific listening situations. For hearing aid owners, the level of satisfaction with hearing aids is quite high, 80 – 88%, in those situations in which it is relatively quiet. Even in small groups we're seeing satisfaction levels at over 80% for owners. When we compare that to non-owners, we find that non-owners have lower satisfaction levels by at least 20%.

In situations that are very difficult and background noise is high such as in restaurants, the level of satisfaction is not nearly as high as it is in the non‑challenging environments. However, even though we do not see levels of satisfaction for noisy situations match those in quiet situations, it still represents a level of satisfaction much, much higher than for those who are not wearing hearing aids. If we look across all situations, we see 80% levels of satisfaction for hearing aid users compared to 40% for non‑hearing aid users.

Comparing MarkeTrak 9 to MarkeTrak surveys from 2004 and 2008, we see continued increase in levels of satisfaction with hearing aids.

When we compare MarkeTrak 9 results to EuroTrak results, we see comparable satisfaction results in the US as compared to Switzerland, which is a sort of homogeneous population with good national health care. There is very little difference between levels of satisfaction between those that have hearing aids in the US and those in Switzerland.

Hours of use. The vast majority of hearing aid owners report wearing their hearing aids nine hours or more, and only 5% wear their hearing aids less than or equal to 4 hours.

Non-auditory benefits. If we look at feelings of rejection and embarrassment, we find that hearing aid owners are less often to report high levels of rejection and embarrassment as compared to non-owners.

Forgetfulness, which may be an indication of cognitive performance, was also surveyed. Those with hearing loss and no hearing aids reported a much higher level of forgetfulness compared to those with hearing loss who wear hearing aids. We are seeing more literature on the effects of hearing loss and cognition. This is not new; Thomas Lunner reported on this back in 2003. He urged that careful attention should be paid to the cognitive status of those with hearing loss as it impacts their ability to utilize their hearing aids.

Amieva and colleagues (2015) published an article that got a lot of attention recently suggesting that those who wear hearing aids have less decline in cognitive performance over time than those of the same age but without hearing aids. We need to be careful in interpreting these results, however, as there were methodological issues with the study. It was not a randomized study. Study participants self‑reported hearing loss, and although it included people who wore hearing aids, we don't know the nature of their hearing aid utilization.

A few other recent discussions on this topic include Weinstein (2015), Beck (2015) as well as Gifford (2015). Robert Sweetow (2015) had an excellent article in Audiology Today last summer discussing screening for cognitive disorders. He identified five screening tests, including the Six Item Cognitive Impairment Test, or 6CIT. That is a very simple test. It was developed in 1983 and is used in primary care. It uses a point system. The greater the number of points, the greater the indication of cognitive impairment. First, you ask the time of the year, and what month it is. You read out an address and the patient needs to repeat it. You ask what time it is. You ask your patient to count backwards, and recite the months backwards. You then then ask them to state the same address you had them repeat earlier; this is like a working memory task. So, as you can see the 6CIT is easy and quick to administer, and can provide an indication of cognitive impairment as a screening test.

To return to non-auditory benefits, we looked at feelings of lack of interest or pleasure. Again, those with hearing difficulty and not wearing a hearing aid express greater degree of lack of interest or pleasure at least in the last two weeks. What is interesting is even those without hearing difficulty reported more lack of interest or pleasure than those with hearing difficulty wearing hearing aids.

Depression is an important topic. Those who are wearing hearing aids report considerable less depression than those with hearing difficulty who are not wearing hearing aids. Those who are wearing hearing aids actually report less depression than those not reporting any hearing difficulty.

The impact of hearing on depression is not new. Tambs (2004) concluded, “Hearing loss is associated with substantially reduced mental health ratings among some young and middle‐aged persons, but usually does not affect mental health much among older persons.” There have also been many more recent studies linking the effects of hearing loss on depression.

Many hearing care professionals feel that it is not within their scope of practice to do a screening test for depression, but that is not true. As a matter of fact, those of you who are part of the PQRS system are now required to perform depression screening tests if you do tinnitus evaluations and expect to get full reimbursement for those evaluations.

There is a list of standard depression screening tools in today’s handout. Thank you to Dr. Robert Fifer for compiling this list. There are many available that are very quick to administer.

Stage 6 – Relapse

The last stage in the Transtheoretical model is relapse. We know what relapse looks like for alcoholics and drug abusers but what does it look like for hearing aid users? It could be that they stop using their hearing aids. That, in fact, they revert to maladaptive communication strategies. What are the risks for relapse? Some of the risks are ones that we can't control, such as major life challenges (loss of spouse, loss of job, loss of independence, major illness/injury) and significant changes in hearing. There are risks that we can control, such as inadequate follow up, unresolved hearing aid complaint(s), and failure to provide post fitting rehabilitation.

In terms of post fitting rehabilitation, we can train the brain and there are many commercial auditory training programs available. These include LACE, Brain HQ, Lumosity and ReadMyQuips. They're all based on gamification, which means using gaming principles for nongaming purposes like health care. These programs address domains such as attention, speed and working memory. ReadmyQuips is a fun kind of audiovisual crossword puzzle. In terms of the research, there is some good data for LACE indicating that it does improve the various domains (Sweetow & Henderson-Sabes, 2007). I have done some research with ReadmyQuips demonstrating improved performance on the Words in Noise (WIN) test.

Quality of Life Improvement for Hearing Aid Use

It’s very apparent from those who responded to MarkeTrak 9 that hearing aid use either regularly (48%) or occasionally (40%) improves quality of life.

Beyond MT9

We know there have been increasing data suggesting a link between hearing loss and other organ systems and psychosocial function. What does this mean for our practices? You need to review your clinical protocol. Upgrade your history to include the co‑morbidities. Explain them but you cannot imply causality, as we don't know that yet. Advise that amplification may improve communications with physicians and general outlook on/engagement with life.

Amplification improved communication with their physicians. Employ meaningful measures of hearing and communication performance. Provide post fitting rehabilitation tools.

Connect and reconnect with your local medical community. Consumers want hearing aid recommendations from their primary care physicians and the majority of physical exams do not include a hearing check. I think it is our job to convince the primary care physicians the importance of hearing screenings.

This journey can be a long one, but with the combination of compassionate, skilled physicians and hearing care providers, along with great technology in hearing instruments, there is no reason why it cannot be successful.

Questions and Answers

I was surprised at the statistics regarding the high percentage of patients that felt hearing aids are a medical device versus a consumer electronics device.

Dr. Abrams: It is an important distinction. When you buy earbuds or earphones, you don't think of them as medical devices. You go online, search for the best price and the best source, and you purchase them. The majority of the MT9 respondents think of hearing aids as primarily a medical device. It may be generational, and this thinking may change over time, but at least for now that seems to be the perception of most individuals with hearing difficulties.

Where can we read a copy of MarkeTrak 9?

Carole Rogin: You can find it at betterhearing.org in the Hearingpedia section of the website.

Do you have any recommendations for making a hearing test more meaningful and impactful for prospective hearing aid wearers?

Dr. Abrams: Yes, I would recommend conducting speech in noise tests such as the QuickSIN, as these tests can help to identify the real world difficulties the patient is having, and patients appreciate that. I think it is also important to provide some kind of a cognitive screening. There is a lot of evidence to support conducting more than just pure tone audiometry and speech testing in quiet for patients with hearing loss.

References

Abrams HB, Kihm J. (2015). An introduction to MarkeTrak IX: new baseline for the hearing aid market. Hearing Review, 22(6):16-21.

Amieva, H., Ouvrar, C., Giulioli, C., Meillon, C.,n Rullier, L., & Dartigues, J.F. (2015). Self-reported hearing loss, hearing aids, and cognitive decline in elderly adults: a 25-year study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(10), 2099-2104.

Beck, D.L. (2015). The state of the art: Hearing impairment, cognitive decline, and amplification. Hearing Review, 22(9),14.

Callaghan, R.C., Taylor, L., & Cunningham, J.A. (2007). Does progressive stage transition mean getting better? A test of the Transtheoretical Model in alcoholism recovery. Addiction, 102(10), 1588-1596.

Gifford, R. (2015). Vanderbilt Audiology Journal Club: Hearing loss and the risk of cognitive impairment. AudiologyOnline, Recorded Course 26609. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K. & Lewis, F.M. (2002). Health Behavior and Health Education. Theory, Research and Practice. San Fransisco: Wiley & Sons.

Johnson, S.S., Driskell, M-M., Johnson, J.L., Dyment, S.J., James O. Prochaska, J.O., et al. (2006). Transtheoretical model intervention for adherence to lipid-lowering drug. Disease Management, 9(2): 102-114.

Kochkin, S. (2009). MarkeTrak VIII: 25-year trends in the hearing health market. Hearing Review, 16 (11), 12-31.

Laplante-Levesque, A. (2015). Applying the stages of change to audiologic rehabilitation. Hearing Review, 68(6), 8-12.

Laplante-Lévesque, A., Hickson, L., & Worrall, L. (2013) Stages of change in adults with acquired hearing impairment seeking help for the first time: application of the transtheoretical model in audiologic rehabilitation. Ear & Hearing, 34(4),447–457.

Lindley, G. (2015) They Say “I Can’t Hear in Noise,” We say “Say the Word Base.” Audiology Today, 27(4), 45-49.

Logue E., Karen Sutton, K., Jarjoura, D., Smucker, W., Baughman, K., & Capers, C. (2005). Tanstheoretical model-chronic disease care for obesity in primary care: A randomized trial. Obesity Research, 13(5), 917-927.

Lunner, T. (2003). Cognitive function in relation to hearing aid use. International Journal of Audiology, 42, S49-S58.

Prochaska, J.Q., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 390-395.

Prochaska, J.O., Redding, C.A., Harlow, L.L., Rossi, J.S., Wayne F. Velicer, W.F. (1994). The Transtheoretical Model of Change and HIV prevention: A review. Health Education Behavior, 21(4), 471-486.

Saunders, G., Frederick, M., Silverman, S., Papesh, M. (2013). Application of the health belief model: Development of the hearing beliefs questionnaire (HBQ) and its associations with hearing health behaviors. International Journal of Audiology, 52, 558–567.

Sweetow, R.W. (2015) Screening for cognitive disorders in older adults in the audiology clinic. Audiology Today, 27(4),38–43.

Sweetow, R.W., & Henderson-Sabes, J. (2007). Variables predicting outcomes on listening and communication enhancement (LACE) training. International Journal of Audiology, 46,374-383.

Tambs, K. (2004). Moderate effects of hearing loss on mental health and subjective well-being: Results from the Nord-Trøndelag Hearing Loss Study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(5), 776-782.

Weinstein, B.E. (2015). Preventing cognitive decline: Hearing interventions promising. Hearing Journal, 68(9), 22-24,26.

Citation

Rogin, C., & Abrams, H.B. (2016, March). MarkeTrak 9 points the way in a time of change. AudiologyOnline, Article 16512. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.