Learning Outcomes

As a result of this learning activity, participants will be able to:

- List three areas where there is a gap in knowledge for audiologists working with young athletes.

- Describe the percent of students who have been involved in systematic transition plans from high school to college athletics and who have been exposed to self-advocacy training.

- Identify a resource that provides guidance in making high school and college athletics accessible to students with hearing loss.

Background

In June 2010, the United States Government Accountability Office found that students with disabilities did not participate in sports or afterschool activities at the same rates as their peers. These students were 56% less likely to play sports. In consideration of the health and social benefits of athletics, the U.S. Department of Education supplied further guidance in 2013 indicating that one reason for a lack of inclusion was that professionals, students, and families are not aware of students’ rights to the accommodations that may make athletic activities accessible.

The book, Time Out! I Didn’t Hear You was published in 1996 as a resource for high school athletes with hearing loss, their parents, coaches, and educational audiologists in order to address some of the gaps that would later be described by the US Government Accountability Office with respect to students with hearing loss participating in high school athletics. The book detailed the technology available to athletes with hearing loss and offered guidance for all involved parties, from clinicians to referees, as to how they could ensure that the athlete could access the sport while following the rules. The goal was to provide a resource that could assist in leveling the playing field while respecting the rules of the sports.

Organized athletics at the college level, whether Division 1-3 or intramural/club level, have the potential to provide students with important social groups, fitness, and financial support for college. As students with hearing loss are underrepresented in high school athletics, they are vulnerable for underrepresentation also at the college level. For these reasons, and because the process of inclusion in college athletics starts in a student’s transition from high school, the authors were interested in producing an additional resource for all stakeholders (student athlete, University Disabilities Officer, high school transition coordinator, audiologist, coach, athletic trainer) who might be involved in making college level athletics accessible to students with hearing loss. The goal of this project was to update the high school text and create a college level text that would be useful to a variety of stakeholders and clearly address the transition to self-advocacy for the college student with hearing loss.

Methods

In order to update the high school resource to include important transition information for high school students interested in participating in college athletics at any level, and to produce a college resource that addressed current gaps in knowledge or action, an implementation science approach was pursued. This included surveying former high school and college athletes with hearing loss as well as posing specific questions related to transition plans to pediatric clinical audiologists and educational audiologists. An implementation science approach was undertaken to ensure that the resource would be useful to student athletes given the transition to self-advocacy that is inherent in college level accommodations. High school-age and young adults with hearing loss were surveyed in order to characterize their experience in athletics in high school and college. Survey questions examined transition plans, inclusion of self-advocacy training, individual approaches to self-advocacy in college, and technology use. In a separate survey, educational and clinical pediatric audiologists were surveyed to examine their awareness of and participation in an athlete’s transition from high school to college related to participation in athletics.

Student athlete surveys were created in Qualtrics and a link to the survey was supplied to individuals accessing the HearYa online group and the Alexander Graham Bell Association listserve (Toole, Palmer, Levine, & Rauterkus, 2017). All responses were anonymous and aggregate data were provided through the Qualtrics analysis and reports. In a separate project, a survey was sent to educational audiologists through a link provided to the membership of the Educational Audiology Association and a link provided via email to two large hospital based pediatric centers in order to assess current knowledge across a number of domains related to promoting accessibility in high school athletics for students with hearing loss (Rauterkus, Palmer, Toole, Levine, & Jorgensen, 2017). Five additional questions related to transition plans were added to the audiologists’ survey for the purposes of the current project. The surveys and data collection techniques were approved by the University of Pittsburgh IRB.

Results

Student athletes surveyed included 33 respondents. Seventy percent used hearing aids or cochlear implants in high school. Three percent of the respondents reported having mild hearing loss, 18% reported moderate hearing loss, 33% reported severe hearing loss, and 42% reported profound hearing loss. Seventy-three percent indicated that they used hearing aids or cochlear implants once they were in college. Seventy-nine percent of respondents participated in high school athletics, while 45% participated in college athletics. Fifty-six audiologists who specifically work with high school and college age students replied to the survey sent out to professionals.

Forty-seven percent of respondents who were athletes in both high school and college reported using the same communication solutions (technological or non-technological) for participation in athletics in college as they did in high school. With respect to general use of assistive technology outside of athletics (i.e., classroom use), the number of individuals using technological (i.e., devices) solutions in college almost doubled compared to those using assistive devices in high school. While the use of technology increased in college, the use of non-technological solutions (e.g., seating preferences, etc.) went from a third of respondents using these solutions in high school to just 7% using similar solutions in college. The use of assistive devices other than hearing aids in high school and in college athletics did not change, however, and remained extremely low. Only 4% of respondents used assistive devices while playing sports at either level even though a number of these athletes used assistive devices in the classroom to improve communication.

When asked who helped in creating solutions for participation in athletics, 65% of respondents indicated that their parents played a role in the process in high school. Thirty-five percent of respondents indicated that they were not assisted by anyone in creating communication solutions for high school sports. This number rises to 60% reporting that they were on their own in seeking accommodations in college while 6% of respondents indicated that their parents had a hand in pursuing communications solutions for them in college as well. An additional 6% of respondents say that the Office of Disabled Services at their college played a role in securing communication solutions. While 58% of high school athletes had help from their coaches in this process; college head coaches and other staff were involved in the solution process for 13% of the college athletes responding to the survey.

We asked questions of both students and audiologists to gain an understanding of the realities of the transition process for students with hearing loss. Thirty percent of respondents reported meeting with their educational audiologist to talk about transitioning to college. If they reported meeting, the discussion included instruction with respect to accessing extra-curricular activities in college for 21% of these students. Education as to how to be one’s own advocate was reported for 37% of these students. Fifty percent of students in the survey who attended college (athletes and non-athletes in the survey) reported reaching out to the Office of Disabled Services upon arriving at college. A third of the athletes who anticipated participating in college athletics reported communicating with members of the coaching staff at their college prior to attending college.

Audiologists reported having a systematic program in place for assisting high school students in developing the self-advocacy tools necessary for seeking accommodations in college at a rate of 26%. When asked whether they considered a student’s potential participation in extra-curricular activities in the development of a transition plan, 39% of the audiologists reported that they have never created a transition plan. Eighty percent of the audiology group reported never having reached out to an Office of Disabled Services at a student’s prospective college. Some of this inattention to the college transition for athletes may relate to the audiologists’ responses indicating that 9% of respondents did not believe that school athletics could be included in an Individual Education Plan (IEP) and 20% did not believe that assistive technology could be used in athletics as well as 14% indicating that they believed hearing aids could not be used during sports because of rule limitations. For the record, hearing aids can be used during sports, assistive technology can be used within the rules of the sports, and accommodations for athletics should be included in IEPs.

Fifty-two percent of the audiologists responding indicated that they did not feel knowledgeable in the area of making athletics accessible to students and desired more information. For many educational and pediatric audiologists, time limitations may dictate that they focus on classroom accessibility. Many may not feel that they have sufficient background in specific athletic activities to recommend solutions. It is important to acknowledge that this survey represents a small sample of audiologists who may be involved in making activities accessible to students with hearing loss, but the results do point to a need for a resource specific to communication solutions for sports and the rules that surround their use may be useful to students, families and audiologists, and other stakeholders. It would be ideal for all interested parties to have the same understanding of the rules that surround these activities and what would be considered reasonable accommodations.

Discussion

Given the results of both the athlete survey and the audiologist survey, it is apparent that there is a knowledge gap in terms of rules and laws regarding appropriate accommodations for student athletes as well as a gap in knowledge of how assistive devices can be used in athletics. The High School edition of Time Out! I Didn’t Hear You was updated to include a focus on needed transition plans and movement toward self-advocacy in the junior and senior year in high school. The College edition was produced to provide needed information to all the stakeholders who may be involved at the college level who may not be familiar with technological and non-technological communication solutions as well as rules surrounding these accommodations. In addition, the section related to special solutions which includes dealing with retention and moisture which can be an issue in all sports when using electronics (hearing aids and assistive devices) was enhanced and updated.

Both books include the following chapters: The Ear, Hearing and Communication, Assistive Devices and Communication Strategies, The Law and Legal Practice, Communication Needs Assessment, Sports Specific Communication Solutions, Officials, and Resources. Two appendices include Statewide Relay Phone Numbers and Protection and Advocacy Organizations. The audiologist may want to review the laws related to sports accommodations for students and then move to the sports specific solutions. Depending on the solution, the reader then may want to refer back to the Assistive Devices and Communication Strategies to see suggestions for hearing aids that work well under helmets and for creative retention strategies that do not interfere with the particular activity. The Communication Needs Assessment Chapter provides a systematic approach to identifying what technology the student currently uses, what new challenges may be posed by the specific athletic activity, and what communication solutions may best address these challenges. For coaches and athletic trainers, it may be helpful to have a better understanding of the impact of hearing loss and the various communication solutions that are available. Likely, coaches and athletic trainers are already familiar with the rules of the sport but the sport specific chapters may be helpful to understand how various technology can fit into the rule structure or where technology may be helpful in practices even if it is not allowed in competition. For parents trying to support their high school or college student athlete, the entire book may be helpful to review hearing, technology, laws related to accessibility, and the rules of various sports when it comes to communication solutions. Our goal was to create a resource that is easy to navigate and useful to all stakeholders working towards inclusion of student athletes with hearing loss.

To access the free download of the books, use the following link: https://pitt.box.com/v/TimeOut

Example Case

The following case is provided as an example of how to use the book as a resource for creating an accessible communication environment for an athlete with hearing loss transitioning into college athletics. This case focuses on an accommodation for use of hearing aids while wearing a helmet which is a common issue for athletes with hearing loss who play contact sports. The solution came about through trial and error in terms of looking for a retention solution and a moisture solution for a particular athlete. The specific solution is described in detail below. In addition to this solution that allowed for successful use of the hearing aids during practice and play, the student athlete had two sets of hearing aids so one set could always be in a dehumidifier. He switched use of the sets of hearing aids after every practice or game, thereby allowing the recently used set to dry out in the dehumidifier. This management strategy as well as the solution described below required a high level of self-dependency/advocacy on the part of the student athlete. In high school, the student athlete’s coach and parents assisted him in keeping track of the devices (the set in the dehumidifier was kept in the athletic office).

The challenge in this case is the transition to college sports. The student will want to continue to use this solution because he knows that it meets his needs. Ideally, the school personnel responsible for assisting the student with transition to college, will start the process early with the student to discuss his needs and current solutions with the Office of Disabled Students at his targeted college(s) and with the coaching staff (often the athletic trainer). Before starting with his college team, the student should have a clear understanding of who will be responsible for maintaining his devices (where will the dehumidifier be stored, who will transition the sets of hearing aids). Most likely this will be the student’s responsibility but the other stakeholders need to be aware of the set up (e.g., athletic trainer, Office of Disabled Students). It will be very helpful if the individuals involved in the student’s high school activities start to transition responsibility to the student during junior and senior year in high school so the student has the chance to practice this level of responsibility with expensive equipment in an environment with a safety net (e.g., parents, coaches) prior to moving on to college.

Solution for a Student Athlete Wearing Hearing Aids Under a Helmet

For athletes who need to wear helmets, they may deal with retention, loss, and moisture. With the concern of concussion, it is not allowable to alter helmets in any way, therefore amplification must be worn within the limits of the helmet used any given sport. Two advances in hearing aids have made use of hearing aids with helmets much easier for athletes.

First, the tiniest hearing aids that fit down into the ear canal can now provide enough amplification for moderate to severe hearing losses. This can be more comfortable than wearing a behind the ear hearing aid. For individuals with more severe hearing losses, they may find that they need the power provided by a behind-the-ear hearing aid. Each individual will have to determine if it is worth the discomfort that might come when the helmet presses against the ear. Regardless of the style of hearing aid, the other improvement has been with feedback control. Hearing aids are susceptible to feedback when objects get close to the microphone, but modern hearing aids have superior feedback control and most hearing aids can be programmed so they will work even with a helmet nearby. The student athlete in this example was able to use IIC hearing aids that produced excellent audibility across frequencies.

Helmets cause additional sweat for most athletes because heat is trapped in the helmet against their hair and scalp. This perspiration coming from the hair/head often flows into the ear canal and may cause the tiny completely-in-the-canal hearing aid to slide out. When a hearing aid slides out during competition, it is very hard to retrieve and, of course, the athlete will not be able to stop play to initiate a search. For this student, two solutions were employed to improve the chance of the hearing aid staying in place or at least not be lost if it comes out of place. The pictures below show a low cost solution for moisture protection, retention, and reducing loss.

If moisture is the primary problem, an athlete can cut off the sleeve of an old t-shirt and wear this as a head band/cap (Figures 1 and 2). It works well because it is inexpensive, very thin, absorbent, and can be washed. Many high school and college players with normal hearing use this solution because it is more comfortable to have the sweat absorbed and not dripping. This solution also can help an athlete control longer hair under a helmet.

Figure 1. Cut off shirt sleeve.

Figure 2. T-shirt sleeve worn over head to absorb moisture before it can go into ear.

If moisture and retention are a problem, the athlete can use the cutoff t-shirt sleeve along with a modification to provide a connection to the hearing aid so it will not be lost if it does come out of the canal. Figure 3 shows a small hole cut into the t-shirt sleeve by the hemmed portion.

Figure 3. Small hole in the t-shirt sleeve.

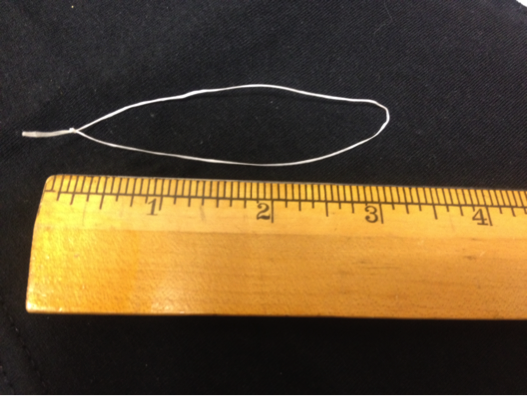

Figure 4. A loop of floss.

Tie a loop of floss (Figure 4). 3 inches is the smallest size that will work and still allow the athlete to insert the hearing aid. The loop can be longer. Loop the floss into the hole in the cut-off shirt (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Floss looped into hole in t-shirt.

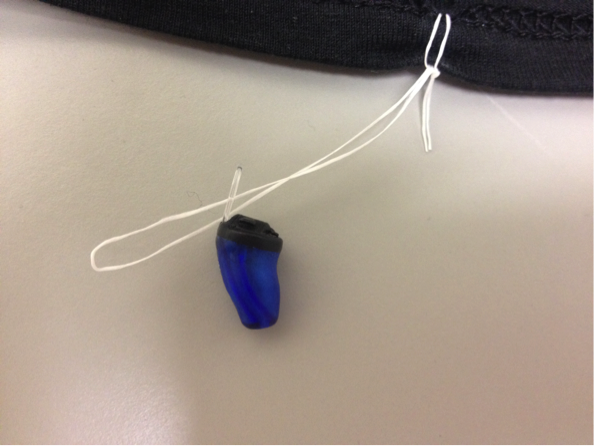

Figure 6. Thread loop through removal loop attached to hearing aid.

When the audiologist orders the completely-in-the-canal hearing aid (or IIC), he/she will request that the removal cord be constructed as a loop rather than a single line. Now the floss that has already been looped through the t-shirt hole, is looped through the hearing aid looped removal cord (Figure 6).

Figure 7. Folded t-shirt going through the loop of floss.

Fold up the t-shirt so it can go through the small loop of floss (a larger loop makes this easier, but it only needs to be done once, Figure 7 and Figure 8). The purpose of this is so the floss will now be looped around the hearing aid retention loop as well as the t-shirt. This design allows the user to remove the floss from the hearing aid after the athletic activity is over without having to cut the floss (although if the floss is cut or broken, it is easily replaced). The floss can stay attached to the t-shirt and this assembly can be washed since it will be absorbing perspiration during athletic activities. The student athlete in this example, cuts the floss each time because that is fast and he finds putting this solution together is easy and not worth the time to unloop the hearing aid after play. He just keeps a roll of floss in his sports locker.

Figure 8. The t-shirt and hearing aid are now attached.

Figure 9. T-shirt, loop, and hearing aid in place.

The athlete now pulls the t-shirt sleeve over his/her head and the hearing aid will be hanging by the ear (twist the t-shirt until the hearing aid is by the ear). The athlete can now grab the hearing aid and place it in the ear (Figure 9). The t-shirt material should absorb enough moisture that the hearing aid will stay in place, but if not, the hearing aid will not go far. This arrangement allows for the helmet to be taken on and off without pulling the hearing aid (which would happen if the aid were attached to the helmet with a clip). Attaching the aid with a clip to clothing does not work well either because the clothing may be grabbed in play, thereby pulling the hearing aid out of the ear. This arrangement uses looped floss rather than a traditional clip because of the concern of the metal clip pushing into the head when there is contact with the helmet.

Summary

The challenge in the transition to college is helping the student athlete continue to use successful accommodations in a new atmosphere where the student will most likely need to take responsibility for specifics related to device care, etc. Moving the student toward responsibility and independence while still in high school will help with this transition. Reaching out to the key individuals in the college setting (athletic trainer/coach and Office of Disabled Students) is essential and should occur well before the student arrives on campus. It may be helpful to provide the resource Time Out! I Didn’t Hear You (available at https://pitt.box.com/v/TimeOut) to individuals who will be working with the student athlete who may not have experience working with an athlete with hearing loss.

References

Rauterkus, G., Palmer, C., Toole, K., Levine, B., & Jorgensen, L. (2017, April). Time Out! I didn’t hear you – College Edition. Poster at American Academy of Audiology conference: Indianapolis, IN.

Toole, K., Palmer, C.,Levine, B., & Rauterkus, G. (2017, April). Athletic accessibility for high school students. Poster at American Academy of Audiology conference: Indianapolis, IN.

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly appreciate the help of Dr. Suzanne Yoder and Dr. Cheryl DeConde Johnson in making the survey link available to target populations of respondents. Kristen Toole and Brandon Levine were instrumental in updating the high school edition and these updates are included in the college edition as well. Thanks to all the athletes and audiologists who completed the surveys. Thanks to Dr. Lindsey Jorgensen and her colleagues at the University of South Dakota for their assistance in obtaining accurate data related to college transitions and college accessibility.

Citation

Rauterkus, G., & Palmer, C. (2018, February). Making sports accessible to student athletes with hearing loss. AudiologyOnline, Article 22232. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com