In a recent article, the inverse relationship between marketing and trust was reviewed: The more money spent on marketing, the less likely customers are to trust you (Garfield & Levy, 2013). This is especially true in today’s era of high consumer expectations and immediate gratification. This article will build on that theme by delving into how the changing needs of today’s healthy agers require audiologists to engage with patients in a more collaborative way. A significant component of redefining audiology’s value to the marketplace is implementing a more effective approach to patient interaction, called motivational or solution-focused interviewing. This approach centers on the audiologist’s ability to guide patients through the process of behavior change that is needed to overcome the consequences of hearing loss.

Let’s examine why motivational or solution-focused interviewing needs to be included in an audiologist’s repertoire of clinical skills. Hearing impairment is one of the most significant chronic conditions in the United States, with a prevalence reaching 90% in the oldest Americans (Lin, Niparko, & Ferrucci, 2011; Nash, 2013). Age-related hearing loss has been independently associated with several co-morbid conditions including diabetes, increased hospitalization, balance problems, depression, cognitive deficits, and even increased mortality (Lin & Ferruci, 2012; Genther et al., 2015). Despite the disabilities associated with hearing impairment, it is often undiagnosed and untreated. The most common treatment for age-related hearing loss, hearing aids, is under-utilized (Bainbridge & Wallhagen, 2014; Lin et al., 2011). For example, Wallhagen and Pettengill (2008) found that 85% of older adults with documented hearing loss who were not currently wearing hearing aids reported that they had not had their hearing tested by their primary care practitioner. In another recent study, Nash (2013) found that 50% of individuals who have seen their primary care physician for a hearing or ear problem had not received a hearing test within the past five years, while 19% exhibited at least a mild hearing loss that might have been identified with a referral for a hearing assessment.

Lack of awareness of the consequences of hearing loss among the medical community, coupled with a clear under-utilization of services are cause for concern for audiologists, especially in light of the large cohort of aging baby boomers. According to Gillon (2004), baby boomers, who are loosely defined as individuals born between 1946 and 1960, control over 80% of personal financial assets and more than half of all consumer spending. They buy 77% of all prescription drugs and 61% of over-the-counter drugs. Due to their sheer demographic size and cultural influence, baby boomers have been known to transform virtually every industry they come into contact with as they age. It’s no wonder the first at-home pregnancy tests become available in the late 1970s when the many boomers were having children, and the first over-the-counter reading glasses were offered 20 years later when boomers were beginning to suffer from presbyopia en masse. Are hearing aids and audiological services the next area of healthcare to be transformed by this group?

Baby boomers have also ushered in the healthy living movement. Since their adolescence, boomers have been at the forefront of various healthy living trends. Fitness and exercise, diet, alternative medicine, consumers rights, smoke-free environments, and other health reforms have been prime concerns for many baby boomers. Perhaps the most recent trend that is extremely popular among mature boomers is the healthy aging movement. Healthy aging is best defined as the ability to maintain optimal cognitive and physical functioning throughout an individual’s lifespan. It is the ability of people to live a safe, healthy and socially inclusive lifestyle. Although individuals over the age of 65 are more likely to be diagnosed with chronic conditions such as diabetes, dementia, hypertension and hearing loss, their outlook toward those conditions is far more optimistic than previous generations of elderly people (English & Carstensen, 2014).

The Shared Decision-Making Process

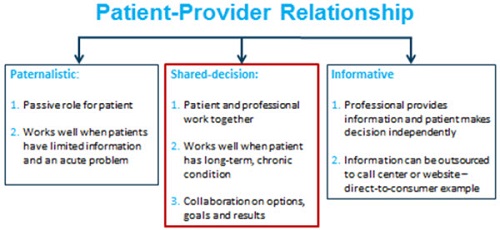

Another hallmark of the baby boomer patient is a need to more actively participate in the decision-making process with respect to their healthcare. To understand the impact baby boomers have had on the healthcare decision-making process, it helps to examine its history. During most of the 20th century, medical decisions shifted from a paternalistic to an informative-based system, which can be plotted on a continuum as shown in Figure 1. In a paternalistic system, the patient maintains a passive role with the healthcare provider and doesn’t take responsibility for the result of the decision. On the other end of this continuum, an informative-based decision, which has become more popular with the advent of automated, computer-based decision-making algorithms, enables patients to autonomously sort through their healthcare options and make decisions independent of their medical professional.

Figure 1. The Provider-Patient Relationship Continuum.

A shared decision-making process allows the patient and provider to work together on treatment options, goals and results. The shared decision-making process views the patient and the medical professional as equal partners in the relationship. Further, the medical provider explains all options and makes a recommendation after taking into consideration the values and beliefs of the patient. Ascertaining these values and beliefs, however, requires time and strong interpersonal communication skills. It is thought that many baby boomers and healthy agers are amenable to a shared decision-making approach (Kon, 2010), thus it would be in the best interests of audiologists to find ways to incorporate this strategy in their practices. Readers interested in the shared decision-making process as it relates to audiology are encouraged to read Leplante-Lévesque, Hickson, and Worrall (2010).

The Patient-Audiologist Relationship

The shared decision-making process may be a more effective way to interact with healthy agers, but it doesn’t adequately address the specific needs of hearing impaired individuals who are likely to have suffered from their chronic condition for several years prior to seeking help. To better understand the shortcomings as well as the opportunities associated with the current patient-audiologist relationship, let’s turn our attention to the traditional patient-audiologist interaction process.

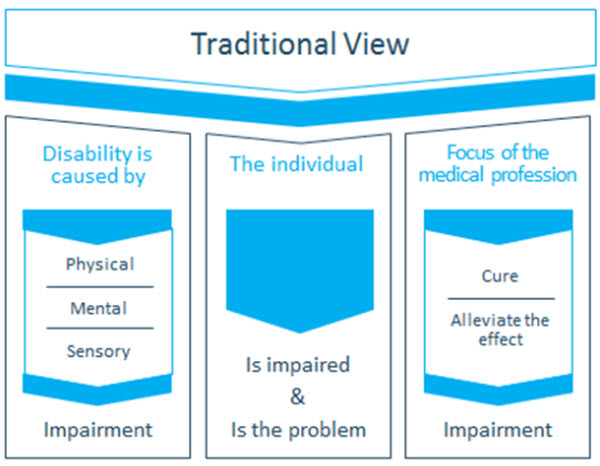

Historically, audiologists, like other healthcare professionals, have been trained under the medical model. The medical model of delivering healthcare requires the professional to focus on searching for the root cause of a condition. The medical model views hearing loss as an impairment with a specific cause and effect. The primary focus for the professional working under the medical model of disability is to find a cure or remedy for the ailment. Under this model, hearing loss is a medical problem, mechanical in nature with a specific cause-effect relationship. The case history and test results are the cornerstone of a medical approach to alleviating the negative effects of hearing loss. (Note: In case you are wondering if you were trained under the medical model, the answer is likely to be “yes,” especially if your training emphasized how to provide patients with a detailed and lengthy explanation of their audiogram, instead of the use of active listening and open-ended questioning skills).

The medical model of hearing loss, which is summarized in Figure 2, is sufficient for otolaryngologists who treat conditions such as otitis media, otosclerosis and acoustic neuromas. It likely falls short, however, for chronic, long-term conditions such as age-related sensorineural hearing loss. To more effectively remediate the effects of age-related hearing loss, a better lens in which to view the world is needed.

Figure 2. The medical model of disability is considered to be the traditional approach to working with patients with hearing loss.

The Social Model of Disability

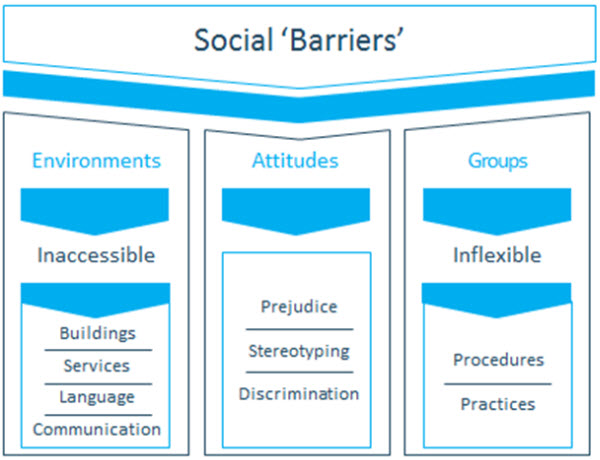

As individuals live longer, healthier lives, the entire healthcare system is increasingly devoted to managing long-term, chronic conditions, rather than treating acute, infectious diseases. The emphasis on managing chronic conditions requires a shift in mindset for audiologists. Rather than viewing hearing loss as an impairment that must be alleviated, audiologists are encouraged to view hearing loss through the lens of the social model of disability. The social model of disability, a concept pioneered by Mike Oliver (1996) in the United Kingdom, emphasizes that age-related hearing loss is a chronic condition. As a chronic condition, it requires ongoing management over time, including the easing and elimination of social barriers. Working under the social model of disability, shown in Figure 3, audiologists must focus on the easing and improving of everyday listening environments as well as societal attitudes. Unlike the medical model of disability, which emphasizes the case history and cure of an impairment, the social model of disability focuses on making day-to-day life easier for the patient who is suffering from a chronic condition that is unlikely to ever be completely cured. At the very center of the social model of disability is society’s viewpoint toward the individual’s disability, and how both the patient and society can modify their outlook and behaviors that result from the disability. For audiologists working under the social model of disability, their primary role is to ease, eliminate or improve social barriers that infringe on effective communication. This process centers on guiding patients through positive behavior change and promoting a healthy outlook with respect to coping with their hearing loss.

Figure 3. The various components of the social model of disability.

Audiologists have conversations everyday with patients about behavior change. These conversations take on many forms. They may involve discussion of accepting the need to arrange the environment differently in order to hear, asking a loved one to speak more clearly, using an amplified telephone more successfully or to simply wear hearing aids more consistently. Regardless of the specific behavior that needs to be changed, the foundation of an audiologist’s role working under the social model of disability is the ability to guide patients through the process of behavior change. This involves a shift in thinking away from the provision of hearing aids as the primary focus, to one where the device is secondary, and requires the use of different counseling techniques.

The Basics of Solution-Focused Interviewing

Motivational interviewing (also called solution-focused interviewing or SFI) is a gentle form of counseling, developed in the mid 1980s as a brief intervention for problem drinking. Although the term motivational interviewing is most commonly used to describe this counseling, this article will use the term solution-focused interviewing because it is more descriptive of the actual counseling process.This form of counseling is certainly not new to audiology, as about a decade ago, several articles were published in the audiology literature (e.g., Harvey, 2003). SFI works well for chronic conditions in which patient action or behavior change is difficult. Given the number of adults with hearing loss that resist treatment or management options presented to them by their audiologist, SFI presents a viable alternative to the persuading and urging that typically occurs during an audiological consultation.

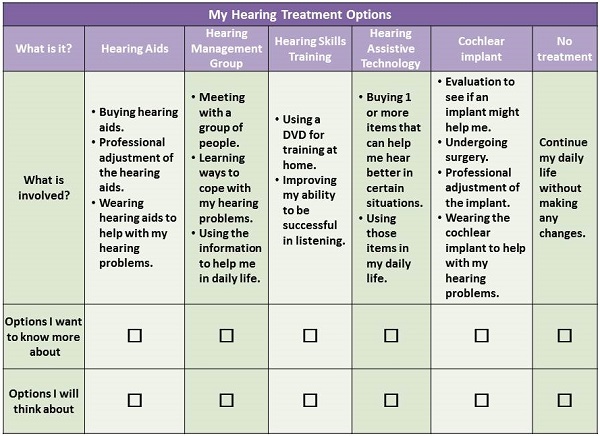

In short, SFI allows audiologists to have more productive conversations with patients about the consequences of their hearing loss and the actions that can be taken to address it. As the name implies, SFI centers on identifying solutions to everyday communication problems, rather than the cause of their hearing loss, or the results of the hearing assessment. These conversation are intended to evoke behavior change on the part of the patient. SFI works by activating the patient’s own reasons or motivations for change. SFI works effectively when the patient is provided a range of possible treatment or remediation choices. For example, the decision matrix shown in Figure 4, which is a cornerstone of the shared decision-making process, guides the patent through several possible options. The role of the audiologist is to review each of the possibilities along with pros and cons of each option, and to collaborate on the decision.

According to Miller and Rollnick (1991), the originators of SFI, the patient’s motivation for change is quite malleable, and these motivators can be modified within the context of the patient-professional relationship. As the authors suggest, the way in which patients engage in the conversation with the professional about their condition has a profound impact on the patient’s willingness and desire to change. All patients have some degree of motivation to change a negative or ineffective behavior, which resulted from their hearing loss. It is simply up to the professional to facilitate the interaction process that will evoke the change.

Figure 4. An example of a decision making aid used clinically (Cox, 2014). Based on Leplante-Lévesque, Hickson, and Worrall (2010).

What Does “Changing Behaviors” Mean?

The core of SFI is providing patients with enough space to explore their ambivalence associated with changing behaviors that are a consequence of age-related hearing loss. During the consultation with the audiologist these conversations are likely to focus on two possible areas. The primary focus of the patient-audiologist dialogue is likely to be on everyday listening situations and how the individual copes in the situations that are most important to him. This includes exploring the ambivalence associated with everyday communication, such as: understanding someone while talking on the phone; understanding when several people are talking; understanding when a speaker’s face is unseen; hearing in a car; understanding speech on TV; comprehending whispering and people in a large rooms; ordering food in a restaurant; following a religious service; and, watching a movie and understanding cashiers or sales clerks. Audiologists are all too familiar with this long list of common situations, all of which present opportunities to explore patient ambivalence with SFI.

A secondary focus of the patient-audiologist dialogue may be on the psychological aspects of long-standing hearing loss. As audiologists are keenly aware, an inability to hear and discern message and meaning can result in patient feelings of shame, humiliation, and inadequacy. It can be highly embarrassing to be unable to behave according to applicable social rules. According to Dewane (2010), the feeling of shame sometimes linked to hearing loss stems from older adults inadvertently reacting in awkward and socially unacceptable ways, such as responding to a misunderstood question in an inaccurate fashion. Older adults may think “How can I stay in control of this situation?” “How embarrassing!” or “What will others think?” Feeling inadequate, stupid, awkward, embarrassed, different, or abnormal are some of the negative emotions that plague older adults with hearing loss when the condition manifests itself over a long period of time. The audiologists ability to explore these underlying feelings and guide actions to address them can be accomplished with SFI techniques.

Communication Styles Used in the Clinic

To fully appreciate the effectiveness of SFI, it helps to have a thorough understanding of the various types of conversations involving a patient and their medical provider. Rollnick, Miller & Butler (2008) refer to communication style as an attitude and approach to helping patients. Each communication style has a different purpose, however some styles are better suited for helping patients than others. These authors describe three main styles of communication between patients and their medical professional: guiding, directing and following.

Imagine you are talking with a loved one about a stressful situation. It is a situation that has far-reaching implications. You have one of three ways to respond. One approach would be to listen carefully and to be supportive without offering an judgments or opinions. This is the following style.

Suppose, on the other hand, that you have a strong opinion about what your loved one should do. You offer a clear and straightforward opinion because you care and want to be helpful. This is the directing approach.

The third approach is a sort of middle route between directing and following. You may listen carefully in order to better understand the situation. Then, you ask about the various options your loved one is considering, along with the pros and cons of each of them. As you gain more information, you may offer a bit of guidance about moving in a certain direction. This, in a nutshell, is the guiding communication style.

All three styles are necessary during a patient-audiologist interaction. For example, imagine using the guiding or following style with patients that need instructions on changing their batteries. However, for monumental types of problems that require behavior change on the part of the patient, the guiding style according to Miller & Rollnick (1991) works the best. For issues related to coping with hearing loss and accepting your recommendation, which is often the use of hearing aids, the guiding style communicates to the patient, “I can help you solve this for yourself.” SFI is a refined version of the guiding style of communication, and it has been demonstrated in other healthcare professions that work with individuals with chronic conditions to generate lasting change (Bannick, 2006).

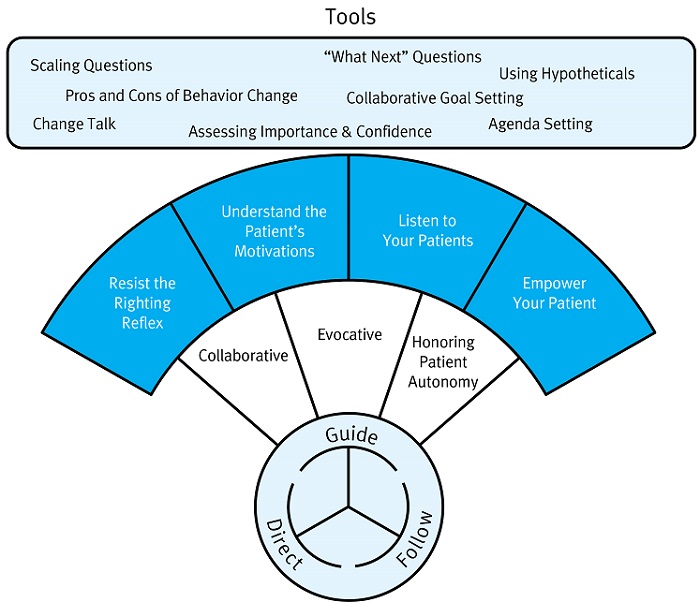

Let’s discuss how audiologists can implement various SFI principles into daily practice. Solution-focused interviewing is a clinical skill used to elicit from patients their own individual and unique reasons to change their behavior in order to achieve a better quality of life. It involves guiding more than directing the patient. According to Miller and Rollnick (1991), the overall spirit of SFI is collaborative, evocative, and honoring of patient autonomy. Rollnick, Miller & Butler (2008), in work that is perhaps more germane to audiology, discuss the four guiding principles of SFI: resist the righting reflex; understand and explore the patient’s own motivations; listen with empathy; and, empower the patient and encourage optimism and hope. Let’s examine each of these four principles in more detail and discuss how they can be applied to an audiology practice.

Resist the Righting Reflex

As highly skilled medical professionals, audiologists are inclined to impose their expertise to promote patient well-being. When we encounter a patient, for example, with a moderate to severe hearing loss, we are strongly motivated to want to select and fit hearing aids as quickly as possible.

Rollnick, Miller & Butler (2008) point out that this inclination to want to “put things right” has a paradoxical effect because it is a natural human tendency to resist persuasion. This is especially true of patients that are ambivalent or indifferent about their situation. Patients with significant hearing loss know perfectly well that there are negative consequences associated with their hearing impairment, but for various reasons they are not ready to take action. When audiologists try to “set the patient right” it is a natural response for the patient to argue the opposite side of their ambivalence by saying that they can live with their hearing loss without doing anything about it. Audiologists then may turn up the volume by insisting even more emphatically that the patient needs to do something about their hearing impairment. This, in turn, is likely to lead to even more entrenched resistance or skepticism.

The remedy for the audiologist’s inclination to “make things right” is to first recognize that it is a natural human tendency for patients, especially those that are ambivalent or indifferent about their condition, to resist your recommendation to correct the problem. The second remedy for this dilemma is to elicit from the patient all the reasons both for and against change. (In the case of the patient-audiologist relationship, change often refers to the patient’s ability to accept the recommendation of hearing aids). In a SFI paradigm, the primary role of the audiologist is to guide the patient through their ambivalence by having the patient state all the reasons for and against changing the status quo. In other words, audiologists can resist the righting reflex by actively engaging in dialogue with patients in which the pros and cons for taking action on their hearing loss are addressed.

Understanding the Patient’s Motivations

The second guiding principle is to take a keen interest in the patient’s own motivations, values and concerns about their current situation. Rather than telling patients how to change, this second guiding principle suggests that audiologists are better off asking patients why they would want to make a change and how they might go about making that change. For the clinical audiologist this can be as straightforward as asking the patient to list all the reasons to try hearing aids and all the reasons to hold off on doing something about their handicapping condition. Another approach that helps audiologists better understand the motivations of a patient is the use of hypotheticals. An example would be asking a patient to, “imagine what it would be like if your family was not frustrated with your inability to participate in conversations at the dinner table. What would that be like for you?” This approach allows the audiologist to help the patient paint a picture in their mind of how improved communication might benefit the patient and his family.

Listening to the Patient

Gordon and Edwards (1997) proposed that active listening (also called reflective listening) should be a vital part of comprehensive medical care. Active listening involves an empathic interest in making sure the audiologist understands the basic needs and motivations of the patient. Simply stated, active listening is described as attentively following the statements of the patient, then restating or “feeding back” to the patient your understanding of what they just said to you. Active listening requires the clinician to put aside their own thoughts and feelings for a moment in order to understand the patient’s unique thoughts and feelings, so that the clinician can try and understand the patient’s view of the world. A second component of active listening is checking on the accuracy of the listener’s cognitive understanding of your message. This is done by paraphrasing the message and “feeding it back to the patient” so the patient can elaborate, modify or correct their message.

Empower the Patient

The fourth guiding principle according to Rollnick, Miller & Butler (2008) is empowerment. The role of the audiologist is to empower the patient to explore ideas and set goals that lead to positive outcomes. By allowing the patient to explore their own ideas and attempt to put solutions into action on their own accord, audiologists are facilitators of behavior change. All of the actions toward that change, however, are made by the patient. A patient who is actively engaged in the consultation is more likely to put ideas into action after the appointment. The act of collaborating on communication goals using clinical tools like the TELEGRAM or COSI, for example, is an effective way to empower the patient.

Another effective type of SFI technique that may be particularly useful for empowering experienced patients, who have perhaps been using hearing aids for a long time, is the use of “what next” questions. Let’s say, for example, that you have a patient who has set some goals to begin using their hearing aid again after a long period on non-use. At one of the follow-up appointments, when you are reviewing the patient's goals for achieving full time use, you congratulate them on their accomplished goal and ask them what their next goal might be. This approach maintains patient autonomy and is likely to result in further improvements in hearing aid benefit.

Interaction Techniques

The core of providing audiology services centers on the patient-audiologist relationship. Thus it is important to discuss some of the basic SFI interaction techniques. The basic approach to interactions in SFI is captured by the acronym OARS: Open-ended questions; Affirmations; Reflective listening; and Summaries.

Open-ended questions, of course, are those that patients cannot answer with a direct “yes” or “no”. Many audiologists begin an initial consultation with an open-ended question such as, "What brings you here today?" According to Perry (2008), the purpose of an open-ended question is to help the patient create some forward momentum that allows for an exploration of behavior change.

Affirmations are statements of recognition about patient strengths. It is conventional wisdom that patients wait 7 to 10 years to seek help. As a result, they come to us demoralized or at least suspicious of the assertion that change is possible. This condition means that audiologists must help patients feel that change is possible and that they are capable of implementing that change. One method of affirming is to point out a patient's strengths, particularly in areas where they may observe only failure. For example, when we genuinely affirm that our elderly patient is making an effort to wear their hearing aids everyday even though they are struggling with communication in certain listening areas, we are offering affirmation. Affirmation requires that we find the positive, even in the most dismal situation.

Reflective listening is a cornerstone of SFI. According to Miller and Rollnick (1991), a goal of SFI is to create forward momentum and to then harness that momentum to create change. Reflective listening keeps that momentum moving in a positive direction. Questions tend to cause a shift in momentum and can stop it entirely. Although there are times you will want to create a shift or stop momentum, most times you will want to keep it flowing. You can keep the conversation flowing by actively or reflectively listening.

Finally, there are summaries. This is really just a specialized form of reflective listening where you reflect back to the client what he or she has been telling you. Summaries are an effective way to communicate your interest in a patient, build rapport, call attention to salient elements of the discussion and to shift attention or direction (Perry, 2008). Also, if the interaction is going in an unproductive or problematic direction (e.g. encountering resistance), the summary can be used to shift the focus of the conversation.

According to Gordon & Edwards (1997), the structure of the summary is straightforward. It begins with an announcement that you are about to summarize, followed by a listing of selected elements, an invitation to correct anything missed, and then usually an open-ended question. If ambivalence was evident in the interaction that proceeded the summary, this should be included in the summary. Here's an example: "Let me stop and summarize what we've just talked about. You’re not sure that you want to be here today and you really only came because your wife insisted on it. At the same time, you have noticed there are places where your hearing is a problem. Did I miss anything? I'm wondering if I am hearing your correctly……”

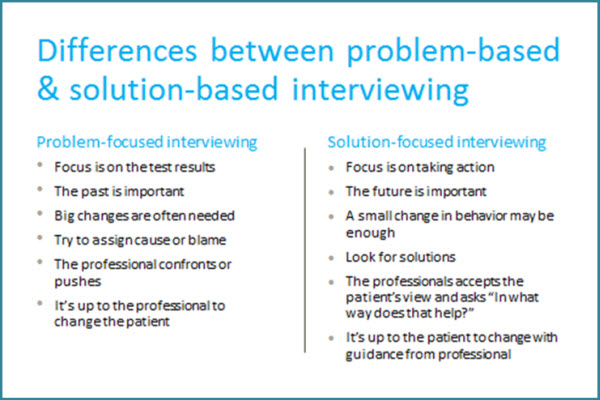

SFI is an effective method for evoking patient behavior change and acceptance of a recommendation for help with hearing loss. In order to understand the true value of SFI, Figure 5 compares SFI to the more traditional approach used in the clinic, problem-focused interviewing.

Figure 5. The key differences between two different counseling approaches.

Change Talk

The goal in using the OARS is to move the person forward by eliciting change talk, or self-motivational statements. Change talk involves communication with the patient that he may be considering the possibility of change. Miller and Rollnick (1991) organize this talk into four categories: problem recognition, concern about the problem, commitment to change and belief that change is possible. For audiologists embarking on SFI techniques, a good place to start would be generating dialogue (or “change talk”) around the following:

- Desire – Why do you want to change?

- Ability - How might that change look to you?

- Reasons - What are the reasons for change?

- Need - How important is it to you to change?

Putting SFI Techniques Into Practice

Putting SFI into everyday practice is not as simple as reading this primer. SFI requires a shift in mindset toward managing hearing loss and its consequences. In order to accomplish this, audiologists are encouraged to enroll in SFI or MI workshops and study groups. For a list of workshops and seminars around the US, see www.motivationalinterviewing.org. Although it’s recommended that audiologists further their knowledge of SFI through continuing education efforts, the patient-audiologist dialogue can be enhanced with some questions that are grounded in SFI thinking.

Keeping in mind that the primary purpose of SFI is to guide the patient through behavior change (not to dispense a pair of devices), it is helpful to devise a list of open-ended questions that hasten this process. Instead of fixating on test results, an exquisite explanation of the audiogram, or features & benefits of amplification, the following questions allow the patient to work through problem recognition, concern about the problem, commitment to change and belief that change is possible. Even for those not formally trained in SFI, a good starting point would be to begin an initial consultation or follow-up appointment with an open-ended question. Then, use reflective listening skills so the patient feels comfortable elaborating on their experiences. Additionally, the following SFI questions ought to be asked of patients during the initial consultation:

- How might your hearing affect daily communications?

- What have you tried to do about specific communication difficulties and what has helped?

- What would you like to see accomplished by the end of the appointment?

- On a scale of 1 to 10 (10 being perfect hearing ability and 1 being as bad as it could get), how would you rate your overall hearing ability?

Figure 6. A schematic overview of SFI or Motivational Interviewing. The circle at the bottom of the schematic denotes the three types of conversations. Important SFI principles and techniques associated with a guiding conversation are listed above it.

Participatory Care

Solution-focused interviewing is a counseling approach that has a very specific goal of allowing the patient to explore ambivalence around making a change in a particular target behavior that is directly related to hearing loss. In an era where hearing aid technology is quickly becoming a commodity as healthy agers demand greater participation in their healthcare, it behooves audiologists to embrace SFI and include it as part of their clinical repertoire. This article was intended to be a primer on the subject. Interested professionals are encouraged to attend a workshop on SFI by visiting https://www.motivationalinterviewing.org.

Despite all of the remarkable technological innovations in amplification features over the past 25 years, there remains a large gap between the number of patients with hearing loss and the utilization of hearing aids. Solution-focused interviewing is an approach that enables audiologists to concentrate on getting patients to take action toward improving or addressing behaviors associated with hearing loss, rather than convincing patients to use hearing aids. In an SFI paradigm, the provision of hearing aids become a means to an end. Taken one step further, proving the efficacy of SFI has the potential to lead to the unbundling of counseling services from the sale of hearing aids and reimbursement from third party payers. This process can only begin with the uptake of SFI among clinical audiologists.

References

Bainbridge, K.E., & Wallhagen, M.I. (2014). Hearing loss in an aging American population: Extent, impacty and management. Annual Review of Public Health, 35,139-152.

Bannick, F. (2006). 1001 Solution-focused questions: Handbook for solution-focused interviewing. New York: Norton.

Cox, R. (2014, April). 20Q: Hearing aid provision and the challenge of change. AudiologyOnline, Article 12596. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com

Dewane, C. (2010). Hearing loss in older adults: Its effect on mental health. Social Work Today, 10(4), 18.

English,T. & Carstensen, L. (2014) Selective narrowing of social networks across adulthood is associated with improved emotional experience in daily life. Internal Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(2),195-202.

Garfield, B.& Levy, D. (2013) Can't buy me like. New York: Penguin Group.

Gordon, T., & Edwards, W.S. (1997). Making the patient your partner: Communication skills for doctors and other caregivers. London: Auburn House.

Harvey, M.A. (2003). Audiology and motivational interviewing: A psychologist's perspective. AudiologyOnline, Article 1119. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com

Kon, A.A. (2010) The shared decision-making consensus. Journal of the American Medical Association, 304(8), 903-904.

Laplante-Lévesque, A., Hickson, L., & Worrall, L. (2010). A qualitative study of shared decision making in rehabilitative audiology. Journal of the Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology, 48, 27-43.

Lin, F.R., Niparko, J.K., & Ferrucci, L. (2011). Hearing loss prevalence in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(10), 1851-1852.

Lin, F.R., & Ferrucci, L. (2012). Hearing loss and falls among older adults in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(4),369-371.

Miller, W.R., & Rollnick, S. (1991). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. New York: Guilford Press.

Nash, S.D. (2013). Unmet hearing health care needs: the beaver dam offspring study. American Journal of Public Health,103(6), 1134-1139.

Oliver, M. (1996). Understanding disability, from theory to practice. London: Macmillan.

Perry, W. (2008). Basic counseling techniques: A beginning therapist’s toolkit. Bloomington, IN: Author House Publishing.

Rollnick, R., Miller, W., & Butler, C. (2008). Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. New York: Guilford Press.

Wallhagen, M.I., & Pettengill, E. (2008). Hearing impairment: significant but under-assessed in primary care settings. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 34(2), 36-42.

Cite this Content as:

Taylor, B. (2015, March). In-clinic success: introduction to solution-focused interviewing. AudiologyOnline, Article 13382. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.