Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live seminar. Download supplemental course materials here.

I am pleased to be joining you today for our third HOPE online program of the season entitled, Keep it Fresh: Ideas for Auditory Work. This is a program that we have brought to you today, thanks to your input. On the feedback form provided to you at the end of the program, we always ask for ideas of things you would like to see in the future. This is a topic that has been requested multiple times to gain more ideas for planning for auditory learning. It is the first in a two-part series called Keep it Fresh. Today's program will focus specifically on activities to promote auditory skill development, and the next session will focus on language goals specifically. I am Ashley Garber, and I am in private practice in Ann Arbor, Michigan. I will share a little bit about myself in just a moment, but I would like to take the opportunity to let you know that Cochlear Americas has various programs available, all designed to reach out to you as professionals in the field and as parents of children with cochlear implants and with hearing loss in general, to broaden the education that we can offer for auditory learning and developing spoken language skills.

As I mentioned, I am in private practice in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and also recently in Farmington, Michigan. I am a Certified Auditory-Verbal Therapist and speech language pathologist by training. In my practice I work with children and adults with hearing loss, some of whom wear cochlear implants. I am very pleased to be able to work closely with Cochlear on developing presentations such as this one and hope that the information that I share today will be helpful for you as you work towards developing auditory skills for children.

In terms of the agenda for this presentation, I will first talk about one model of auditory skill development. If you have viewed a presentation that Mary Ellen Nevins or I have given in the past, you may be familiar with the model that I show you today. It really is a review. We will take a look at that model to orient ourselves to where we are and what we are talking about in terms of auditory function. I will then take a look at some of the subskills of auditory function, and then we will jump right into therapy plans for expanding context as we work towards auditory comprehension.

Parameters of Auditory Skill Development

Auditory Function

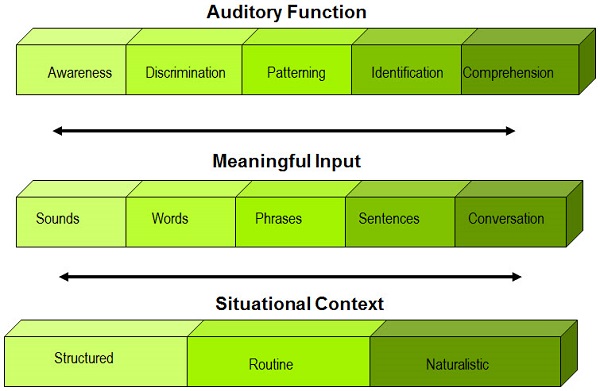

I will remind you that as we think about how auditory skills grow and change over time, we think of three parameters. Building on the work of Norm Erber from 1982 who mentioned the auditory function and the meaningful input parameters, we will add a third parameter to that. The first area is auditory function, where we look at the awareness of skills and identification, moving towards comprehension. These are all the tasks of listening that we will ask a child to do, and they are hierarchical in their developmental nature. We look for a child to be aware of the sound or of speech or of conversation first, and then move toward identifying features, and later towards comprehending the information embedded in the message.

Meaningful Input

Meaningful input is the second parameter that I mentioned. This is the parameter where we consider the auditory stimuli that are presented to listener; these are the stimuli from which we can derive meaning. These skills build from environmental and speech sounds, these smaller bits of input toward conversation, to a bigger, more complex level, but we would not necessarily call this area hierarchical in a developmental sense. Children receive input across this range from the very beginning. Of course, they are hearing isolated environmental sounds and simple speech sounds because we break things down for them, but at the same time they are hearing conversation around them. So developmentally, we can input all of these things from the beginning as we work towards developing auditory function.

Situational Contexts

The third parameter to consider is situational contexts. This is the one that we will consider in the most depth today. I think it is the most impactful in terms of planning for our therapy sessions or classroom activities. We can think about how to contextualize the listening tasks that we are doing and the information that we are asking children to learn so that we can move most quickly from a structured didactic learning task towards more real-world conversational competence.

If we think about situational context, we first involve children in structured listening tasks, which are specific activities that are designed to practice auditory skills. Within structured listening tasks, we might think about closed-set tasks, where all choices are available to a child. For example, a closed-set task would be asking a child to select one of four items that are pictured or placed in front of them. In contrast, an open-set task is one in which the possibilities for stimuli and response are endless. We ask a child a question out of the blue, and that would be open-set question; the child has limitless choices from which they can choose their response. In-between would be a bridge set, and that is a way to move from a closed-set structured task towards an open-set structured task. This would be where the responses that are available to a child may be created through less a visual set. For example, if we give a child a topic, instead of putting four or five items on the table, we say to them, “I am thinking of an animal.” Instantly there are specific choices that the child has, but it is a much larger set than if we put a few things on the table. It is also more of a thinking set for the child versus a visual set. That can be a bridge that you can use to move between pictured items you have presented and an open set. They still have some limitations within their thinking, but it is a much bigger set then the visual set would be.

The next more complex context in which we would begin developing skills would be routine activities. These are recurring events that are associated with predictable language. There are things that happen every day in a child's environment such as getting dressed, having a snack at school, going through homework review, et cetera. Things that have any predictable pattern to them would be considered routine activities. A step beyond those structured routines are naturalistic exchanges.

Naturalistic exchanges are those real-world conversations in which the child's ability to listen transcends the activity that you are doing or the environment they are in, so that if you ask the child a question that is not specific to what is right in front of them, they could understand it because they truly understand the language that you have used and the information that is presented to them. They are able to show comprehension through novel response, showing that they do understand and they can listen regardless of whether or not the information presented fits with what they are doing right at that moment. That would be the most naturalistic sort of environment. Conversations are where a child follows what other speakers are saying. This is the most naturalistic way of communicating, so that would be the ultimate context through which we are moving.

Figure 1 shows a graphic representation of the levels that I just mentioned. With auditory function, there is awareness, discrimination, patterning, identification, and comprehension. These are hierarchical in nature, and a child will develop their skills from the base skill of awareness towards that more complex skill of comprehension. Skills will always develop in that order. The arrows are indicating that the levels move back and forth. This just shows that we have skills that build, sounds build to words, phrases, sentences, and conversation in terms of input. Those do build, but a child is exposed to these at all times, so we can vary the input that we use. We can also vary the situational context in which we present information so that we can monitor their development in all of these areas. But we can also present information in all of these different ways so that we are challenging a child's auditory skill development from the beginning, with the ultimate goal of comprehension in a naturalistic setting.

Figure 1. Continuum of auditory function, meaningful input, and situational context.

Subskills of Auditory Comprehension

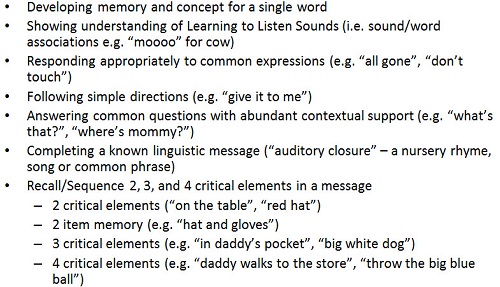

With that quick review of the auditory skill model behind us, remembering that we are highlighting the area of context in our discussion today, I will move now to talking about some of the subskills of auditory comprehension. I will be pulling some of these out to discuss specific activities that we can devise to target particular subskills. I have pulled together goals as they were written in Warren Estabrook's (2000) book. He has a whole auditory hierarchy, a sort of curriculum of subskills. Beth Walker (1995) in her informal Auditory Learning Guide presents subskills of auditory development also. I have pulled together goals as worded in each of these references (Figure 2). There are multiple curriculums out there that include similar information, but I have chosen to use the language as presented by Estabrooks (2000) and Walker (1995).

Figure 2. Subskills of auditory comprehension (Estabrooks, 2000; Walker, 1995).

Some of the subskills of auditory comprehension are developing memory and concept for a single word. With that very small level of input, the word, we are already talking about comprehension, which is one of the higher levels of auditory function. We do not have to move step-by-step from identification of a sound to identification of the word to identification of the sentence level/phrase. That is very didactic type of learning. We can group from the very beginning and start thinking about developing comprehension with single words, showing understanding of different concepts. Here we look at those skills.

If you are familiar with some of the terminology used often in auditory-verbal practice, Learning to Listen Sounds are kind of iconic. These are things like “mooo” for a cow or “beep beep” for a car. Next is responding appropriately to common expressions, following simple directions such as “Give it to me,” or answering common questions that might happen with abundant contextual support, for example, “What’s that?” or “Where's mommy?” Completing a known linguistic message is what we call auditory closure. This would be like presenting a nursery rhyme or song and stopping in the middle, and then waiting for the child to complete the message from something very familiar to them. Recalling or sequencing involves various levels of critical elements starting with two critical elements such as “on the table” or “red hat,” two-item memory such as, “hat and gloves.” You see the difference there. I tried to show a little bit of difference between critical elements and items. Some children do very well with remembering a list of objects but have more difficulty with critical elements that are perhaps grammar related or descriptive words instead of object labels. That is reflected in the subskills that we look to address: two critical elements, two-item memory, three critical elements, four critical elements, and item memory for each of those as we move upward through the hierarchy.

Next is identifying a picture related to story presented auditorily, answering common questions about a familiar topic, answering questions about a story, and identifying an object based on several related descriptors. This is one that might be a little bit confusing. This is where, as a speaker, we use descriptive information to tell about something, and the listener has to put pieces together to understand what we are talking about. For example, it could be structured like, “I am thinking of something that you eat for breakfast that you put in the toaster,” or it could be descriptions with colors or other descriptive words. In a natural situation, we do this all the time. It is that instance when you cannot think of a word, so you have to describe it to come up with the label. This is an area that I will give some activity examples as we move forward in the program today.

The next goal is recalling or sequencing multiple elements to follow auditory directions. Something that we have talked about in other programs is the idea that these are auditory goals. This is focusing on the listening aspect of the language that we use, or the specific auditory information that a child has to act on, think about and then use in their response. As we overlay language onto these auditory goals, we will find the need to sequence back through these auditory skills. For example, a multi-element direction could be something like, “Draw a red circle and a blue square.” That is a direction with four critical elements: adjective, noun, adjective, noun. Red circle, blue square. Because we have given a direction, the assumption might be that we are drawing everything within this activity. Draw is not necessarily a critical element; the four critical elements are the color and the object labels. By that same token, a more complex four-element direction could be even within the same type of activity, “Draw a squiggly shape over at the bottom.” I am using prepositions that are more specific or complex. So we can cycle through as we increase our language expectations. For a child that is building their language skills, we may still be at the same auditory level. Perhaps we cycle through some of these higher-level auditory goals as we move through language and grammar structures and vocabulary. We can use the same auditory goal and increase the difficulty of the language that we are using.

Up to this point we have been reviewing some of the information of the auditory skill hierarchy and of auditory skill development to put us in place for the therapy plans that will talk about. I did choose to focus on those auditory comprehension goals that I shared with you. Of course, there are auditory goals for sound discrimination and for word-level aspects of word discrimination, such as speech babble, that are going to come into play, but I think what people are asking for when they are thinking about creativity in lesson planning has to do with some of these higher-level comprehension goals and how they can expand the activity offerings that they make for children. What I have for you today are activities related to those auditory comprehension goals.

Therapy Plans for Expanded Contexts

As we move through these, I wanted to bring forward a few key principles. The first is that the path to generalization of skills should always be on our minds. We really would like to move as quickly as possible towards development of skills in naturalistic exchanges. Even for a very early listener, we want to think about identifying Learning to Listen Sounds. We do that in our therapy room and we talk to parents about new sounds of the week and how we are going to play games to pull out the sounds and use acoustic highlighting, but we should also be talking with them about using those sounds at home. It is a naturalistic exchange for the child when they hear the sound out of the blue or hear the use of a particular word. That will be on our minds all along the way.

Individual and parent/child therapy is a great place to work on the structure tasks, because we can control the input and the materials that we use in that situation. We have a structured environment. We can work on structure tasks. The classroom, on the other hand, is a place that is full of routine. Even a preschool classroom has snack, story time, calendar time, when we leave and when we stay; all of those things are built into a daily routine to help children with their expectations. The same holds true for the general education classroom as well. There are many routines that are built into the day. These are great times to work towards that next step of following success at the structured level. Perhaps we are talking about working on a particular skill in the therapy room in a structured way, passing that goal to the teacher to develop in that routine setting. Both the therapy room and the classroom offer lots of opportunities for naturalistic exchanges, but sometimes it takes creativity to make that happen. What I hope to share with you today are some ideas for turning those structured and routine events into opportunities for naturalistic exchanges.

I have taken a couple of these higher-level comprehension goals and tried to present some different ways that we can work towards those goals in our therapy room or classroom setting. For example, the first is recalling critical elements in a message. As I mentioned, you can take this in two different directions. The first would be with keywords so something like “red hat” or “on the table.” Both contain two keywords. It could be memory for two objects, such as, “Get the ball and the book.” As we increase the difficulty, we might include three critical elements such as “in daddy's pocket,” or “big white dog.” Four critical elements would be, “Daddy walks to the store,” “throw the big blue ball.” You can make a memory for list of three, four, or five objects accordingly. We have talked about that already.

Here are some games that you could play for auditory memory: making a bead necklace for mom or drawing a picture for mom. Perhaps we are going to make jewelry. This is of course likely to be a closed-set task, because to make a craft like this, the materials have to be handy. These are things that are going to be visible to the child. It is something that lends itself to that structured environment. If you ask the child to make something for someone else, it gives you a reason to give them directions, versus if they are making something for themselves and they get to choose whatever they want. I am giving the directions there, such as “Let's put blue, red, and yellow next.” That is a very simple sequence, asking for just a list of three things with very familiar vocabulary.

Another idea can be drawing a picture, where you are giving directions again. “How about drawing a sun, a bird, and a flower?” Again, this is a pretty simple and familiar activity. The creativity for drawing a picture for mom is not way out there. I did want to point out that thinking about the activities that you do can sometimes give you insight into some of these features. For example, drawing a picture. The expectation of what makes a nice picture for a child of a certain age does turn this into a bridge set. Give them a completely blank page and describe things. Often this is going to be more of a bridge set than an open set. For example, if you ask the child to draw a house, their expectations will lead them to immediately think of a door, windows, some grass, perhaps some flowers, a sun shining overhead, maybe some clouds and a bird. I think that is a pretty standard picture for young elementary-age child. Even if we have thought of this as an open-set activity, the child’s expectations might turn this into a bridge set, or we might really want to think of this as a bridge-set activity. Your challenge might be to be more creative in your own directions so that you are turning this activity into an open set by considering that the child will have certain expectations for what might make a nice picture.

Here are some more slightly creative ways to sort of sneak in auditory memory. One is sort of a variation on fun car trip games. In my house, we call this game Three Things. “I will list three things and your job is to be the first person to find all three.” You give an auditorily-presented list, and the child has to remember these things as they look for them out the window. Of course, you can play it in your therapy room or as you walk down the hall from the classroom to the therapy room, or maybe in a group on a class field trip. You can turn it into four things or five things- whatever is appropriate for the auditory memory level that you are working on. One nice feature of this game is that the opportunity for some delay in memory is built in. The child has to hold those objects in their memory for longer, which is an important step on that hierarchy of auditory skills.

Next is secret code. This is sort of a sneaky way to fit in auditory memory. Perhaps each day in your classroom, you present a code at the beginning of the day. It could be a list of words to remember or a word that you are spelling out. Maybe it is a list of numbers, but the child has to remember the order, and that code is required by the child from memory to open the prize drawer the end of your therapy session, for instance, or to get the candy dish to open at home or to have use of the TV remote for after-homework time. This is a kind of activity where the child has to use their listening memory to remember the objects that are named. Holding it in their memory is required with this game as well.

There is an expectation that children will do these tasks in this explicit order. In terms of auditory memory, you will be building from a smaller set to a larger set: two items, three items, four items and five items. Within that goal, a list of objects tends to be easier for children than critical elements where those critical elements are embedded into other things, because some of those other things can be distracting with other grammar elements. Also, if you are cycling through language, sometimes the critical elements are grammar elements that are more challenging. These can include prepositions, adverbs, or adjectives. Sometimes those are the things that are a little less familiar, and they can be more distracting. I think that is why a list of objects is going to be easier to remember than the critical elements. As I mentioned, you will be cycling through language so that you will develop memory for three or four critical elements at a simple stage. Then as you build, you will go back and be using harder language, still at that three or four critical element level. You will move beyond and then go back. The subskills in general, as I mentioned, are pretty hierarchical, starting with the auditory closure for familiar songs and poems and things like that, then moving towards auditory memory goals which are a little bit more difficult. I did try to present them in kind of a hierarchical way.

The next feature is what I call the “Let's go to…” activities. I have tried to repeat this throughout each of the goals. This is a way of considering this in the most naturalistic sort of way. I have given you some very structured activities to do for this goal and some more routine things, such as “Let's go to the hamburger joint.” Here is a way to work in auditory memory in more of a pretend play setting. You could also consider coaching a parent or sharing information with the parent to do this in a very naturalistic way. Go to a hamburger restaurant and order something for the family. So mom says, “Please order me a hamburger with tomato, cheese, and lettuce,” and the child has to remember that to place the order. Within the therapy setting, set up a little hamburger joint and play the “have it your way” game, where one person pretends to be the fast food worker and one person is the customer. The customer gives their order asking for three things or four things. A list of items might be tomato, cheese, lettuce, pickles, ketchup and onions.

I have given some examples for cycling through the language as well. Maybe the language becomes more complex for children that are further down the language road, so you might have them ask for “everything but pickles.” Those three words are all critical elements, because they each have meaning to the outcome. Chopped onions and shredded lettuce are four critical elements. Manipulate the variables. You can increase the size of the set. You can increase the requirements made on them auditorily. In my therapy room, I actually play this game sometimes with cutouts made from craft foam. I have cut out hamburger patties, cheese squares, pickles, olives, and lettuce leaves. There is a counter set up with all these things and when the person gives their order, then the fast food worker has to assemble the hamburger in that way. You can give them more things to work with to increase that set size and make it challenging, or you can bring it down depending on how difficult you think it might be for the child. Of course, the hamburger joint is just one example.

Subway is another restaurant where you put yourself in the place of the worker and see if you told them everything that you wanted on your sub sandwich. How many things would they have to remember? How many things does a barista at Starbucks have to remember to get your order right? Those can be quite complicated. That is definitely an auditory memory task. You could set up something similar in your therapy room depending on the age and developmental stage of your client. This can expand to all sorts of scenarios. “Let's go to the grocery store. I need oranges, milk, soup, and bananas.” “Let's go to the laundromat. Put the red pants and a striped shirt into the washer.” “Let's go to the ice cream parlor. Three scoops please: vanilla, chocolate and cherry.” You see the auditory memory built into each of the directions that you have given here.

The next goal that we will consider is identifying a picture related to a story presented auditorily. One idea might be for the speaker to describe an event that is pictured in the child's experience book and have him find it. That is something that could be quite structured if the child brings an experience book to therapy each week, or it could be a more naturalistic when the child sits down next to grandmother and they just look through the book and are enjoying that. It would be something that you could work in or help grandma to understand to work in there. I like the idea of using newspaper photos, because photos do capture entire stories with one image. They can be a great tool to address this goal for older listeners, because what we are looking for is for the speaker to provide the stimulation level as several sentences that the child is listening to that are going to describe one thing. The newspaper photo is an excellent stimulus for that.

Recalling story elements in sequence is another goal for you to consider. For closed-set tasks, the key is to choose pictures that do not give away the sequence visually. Something I have in my therapy room is little three-part puzzles in which a story is depicted. For example, first the cat finds a balloon, next he blows up the balloon, and in the third picture the balloon gets bigger and then it bursts. These are materials designed to teach a child the concept of sequencing, but what we are thinking about is the ability to recall auditory elements and put them in sequence. A material that shows the sequence visually is perhaps not appropriate, because you want the child to actually be listening and then using the auditory information to do the sequencing. Something that I really like from eeBoo is called Tell me a Story. These are just card decks. They also have some games with the similar images. One is a circus set, and then there is one that is a fairytale set. There several options. There are groups of pictures that are related and could easily visually relate to the same story, but they are also common elements, and you can interchange the different little stories sets. It is a nice material to use when you want to tell a story and have the child sequence it purely based on their comprehension skills. In the open set, there really are no limits to how you can do this. You might want to try incorporating this goal of recalling story elements in sequence into the creative framework of another activity.

If you have joined me before, you know that I use that term, “creative framework” to talk about the reason you give a child to play with a particular toy. For example you might tell them a story about why you are going to do another particular activity, and then have them repeat that back to their parent or their sibling or their classmate. “Ms. So-and-So said we have to do this because ….” and then tell the story in that sequence. It is something you can sneak into other activities in that way also.

Here is a fun, naturalistic role-playing game that you can play. It is called “Let's Go to the Library.” I love to incorporate these sorts of scenarios into my therapy room. I try to do something real-life in each session, because I find it is a nice way to fit in pragmatic language as well as the particular grammar and listening goals that I am working towards. Let’s Go to the Library is one where I set up a little table that has several books on it. One person is at home and tells the child that they really want to read a particular book, and will the child go to the library to find it? For example, you might describe the story this way. “I'm looking for a book where a little girl sneaks into the bear's house and causes trouble. She eats all the soup and breaks chair. Then she falls asleep in the bear’s bed. Soon the bears find her and get angry. The little girl is so scared that she runs home.” Obviously we are talking about a child who has developed language to the extent that they are listening to this story and then they are going to remember that information, run over to the library, retell the story to the librarian, so that librarian will help them pick out the book. That may be at a higher-language level, but the game can certainly be modified so that what they are doing is using their auditory information. That is really that auditory goal that we just described. They have to identify the book jacket in order to pick the book out, check it out, and take it home. Then you have the opportunity of going through all the social language and vocabulary that you use at the library to check things.

Another way to modify the game is by having the listener remember and retell the story to the librarian or book shop owner so that they can help you find the book. There are lots of ways you can modify it so that there is more or less information or so the information is presented visually, and the child can use that to achieve the task.

In another task, the goal is to identify an object from a series of descriptors. Some closed-set games that you might use to address this goal would be variations on the Guess Who? game. Guess Who? Is a game probably familiar to most of you. There is a character that is selected, and you have to describe that person or ask questions of the other player so you can determine which person they have hidden. There are some variations on this, also. There is an app called Guess ‘Em, which is designed for use with two different devices. You can use two iPads or an iPhone and an iPad or an iTouch, and play as partners that way. It can certainly be played as one player. I have played it many times with just one device where you decide for yourself which person you are thinking about and then either ask questions as you would in a traditional game or give a description. In this case you might say, “I am thinking of the person who is wearing a red shirt and has a mustache and brown eyes,” and then child has to guess which person it is based on that description. The Guess ’Em app has several choices of playing boards. They put out seasonal boards so there are Halloween characters to describe, maybe dragons and knights, different theme sets which would open up opportunities for different vocabulary as well.

Another modification that I have made using the Guess Who? game is called Stop Thief! One variation that I do with the Guess Who? pieces is I play Stop Thief! where someone is the police officer and someone is the witness to the crime. We will hide a bag of money under one of the pictures. The police officer is out of the room. When the police officer comes back, he or she has to question the witnesses to find out who took the money. Depending on your language or listening goal, you can have the person ask questions and have different listening roles, or you can have them describe the thief like, “The thief had blonde hair and glasses. She was wearing a red hat.” Then the police officer listens to the information and uses those descriptions to identify who stole the money.

There is another app called The Bag Game, in which a paper bag is represented and there are little objects of different theme sets that you can hide in the bag. Then you take turns describing what is in the bag for the person to guess before you open the bag and show what is inside. For those of you who do use technology and apps in your therapy sessions or your classroom, there are a couple of ideas for you. Any lotto game or matching game set that you purchase would be an ideal material for this kind of identifying from a series of descriptor. Storefront bingo is a favorite that I have mentioned before in various sessions. Again, I like eeBoo materials because they present lots of different vocabulary aspects that are not presented in some of the more standard toys out there.

For the bridge set or the open set, variations on I Spy will get you where you want to go so that you do not have to necessarily use materials. You say, “I spy something that is used for…,” and then describe it. The child has to guess or look around to see what you might be describing. Next is the Magic Bag or the Empty Backpack. I like to do activities where there are no materials present, because you have the opportunity to you make the set whatever you want. If you have a backpack, maybe the bridge set has been described for you because you have the backpack. So the things that are inside are likely about school or things you would pack in a backpack for camping. You reach in and you pull out nothing, but you tell them, “I have something from the backpack that takes batteries and gives off light.” They can try and guess flashlight or whatever it is. Those are other kinds of bridge activities you can do.

To make it more naturalistic, play Let's go to the Hardware Store. I personally do not know all the names for the tools and gadgets that are available in the hardware store, so it is pretty natural to describe those things instead of name them, because I do not know the names. I can say, “This is something that you used to make wood smooth,” or “This has a long handle and you have to twist it.” This can be a closed-set game because the child likely does not know the vocabulary for this either, but the objects are present there in the hardware store. The child plays the shop owner and someone comes in and asked for the tools that they need to finish a certain project. The child has to listen and ask, “Is this the tool that you need?” That gives you an opportunity to feed in any vocabulary that you do know.

To work with auditory memory, recalling and sequencing multiple elements to follow auditory directions works well. Making paper crafts is a great structured activity that you can do with auditory directions. Make a paper airplane or making one of those origami balloons, or for middle school kids, those little paper games that you and point to numbers, they follow directions, and then there is a boy’s name inside the flap or whatever. You can certainly give directions to someone else to make something like that.

Have the child set up a game that you will play for speech re-enforcement. This is another way to overlap your goals. I always play dumb with the different games, and sometimes I ask the child to give the directions, but if we want this to be an auditory goal, then I am going to give the directions and they have to set it up. For example, “Give three balls to Jacob and put the rest in the basket.” Then there might be additional directions that you give to get everything set up so you are ready to play the speech reinforcement game. This is a quick way to incorporate following directions into a structured environment or in a structured way, but something like that obviously could be done in a classroom environment or a home environment as well.

For that naturalistic opportunity, use “Let's Go to a Cooking Class.” “Today we are going to make oatmeal cookies. Pour the oats in the bowl and measure 1 cup of flour. Pour the milk into the flour mixture.” The natural discourse is present for the child, but a cooking activity is a structured task. The question to you will be what kind of set you consider the scenario. Is cooking usually a closed-set task or is it a bridge set or an open set? Giving some thought to these sorts of things, even if no materials are present, I think you could argue that this is more of a bridge set. For any child who has had any kind of experience at all in the kitchen, there are certain things that we expect are going to be named or asked for. Furthermore, there are certain words that are not going to come up in that scenario. I think a bridge set might be what we consider this activity. Have in mind exactly where you are targeting or know your goal so you can look to say, “I need a bridge set. This is a great activity for that.” With something like this, it is pretty easy to manipulate the variables. You can bring everything out and only have three or four things available for the child to choose from. It is also easy to cycle through language goals. You can make the example that I gave more simplistic or much more complex in your directions, and you can use higher-level vocabulary as well. There are lots of different ways you can take this while still focusing in on that particular auditory level of following multi-element directions.

Questions and Answers

What is eeBoo?

eeBoo is a brand name. It is a toy company. I love their materials. I have memory games that present the same preschool vocabulary over and over again like airplane, ball, house, crayons, and cup. But eeBoo puts out materials that have much more varied vocabulary. All of their toys are what I would consider infinitely flexible, and they can be used with a variety of ages and for any auditory or language level. You can use them in so many different ways. You can get eeBoo material from Amazon, different toy companies, and in different toy stores.

How much do you work on auditory and language goals simultaneously versus addressing auditory and language skills separately?

I would say it is almost always my habit to work on them together for a couple of reasons. For almost every activity I do, I have an auditory focus and a language focus. Sometimes the language used for the auditory part might be a little bit different than what I am expecting, if the language is an output goal. Maybe the levels are different. For example, on a child's turn as the listener, I might present one level of difficulty, but when they are the speaker, the language expectation might change a little bit based on where they are with their goals. Almost every activity I do has both a language and a listening goal.

Is there a book specific to pre-K goals and objectives?

I think you are looking for some sort of curriculum or guidebook that specifically talks about pre-K goals. I am not sure I have a specific answer to question. I would think more in terms of language level or auditory level. For example, the goals I presented to you are all the auditory goals that take a child from early listening skills all the way through higher-level listening skills. Each child moves through them at a different pace. For a middle schooler who has limited auditory access or perhaps recent auditory access, I might be working at an early listening level, but with middle-school-level input in visuals and things like that. Maybe I have worked through all these goals, but I am working towards higher language levels. I am still asking the child to focus on their listening to get to higher-level language. In terms of specific books with goals and objectives, I do not know one that talks about preschool or kindergarten specifically.

References

Erber, N. (1982) Auditory Training. Washington DC: Alexander Graham Bell Association.

Estabrooks, W. (2000). Auditory verbal practice. The Listener, Summer.

Walker, B. (1995). The Auditory Learning Guide, unpublished. Retrieved from https://www.firstyears.org/c4/alg/alg.pdf

Cite this content as:

Garber, A. (2013, March). Keep it fresh: Ideas for auditory work. AudiologyOnline, Article #11691. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com/