Editor's note: This article/text course is an edited transcript of a live webinar. Please download supplemental course materials.

Dr. Bankaitis: This is the second part of a two-hour series on infection control on AudiologyOnline. The first course is entitled, Infection Control: Why Audiologists Need to Care. That course focused on why audiologists need to implement infection control in the clinical setting, what infection control means, why we should care, and what we need to do to get ready to create and implement an infection control plan. This course is about the nuts and bolts of the infection control protocol. If you have not yet reviewed Part One, you will still benefit from the information that we are going to be reviewing in today's course.

The specific goals of this presentation are to identify and review the written infection control plan, build upon the concept of what a work-practice control is and its role within an infection control plan, and discuss key points associated with selecting appropriate product for use in the clinic for minimizing the spread of disease. After this course, you should be able to demonstrate how to create these comprehensive work-practice controls that are based on established rules and guidelines. We are going to outline exactly what needs to be done, and what I think is the best way to go about doing it.

Written Infection Control Plan

I think all of us know that an infection control plan is important. A fair question to ask is, “Is a written plan really necessary?” The answer to this question, unequivocally, is yes. If you reside and practice in the United States, the correct answer to that question is yes. Infection control is a federal mandate overseen by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, which is the federal regulatory agency that is responsible for overseeing safety in the workplace. Infection control falls under the safety umbrella that is dictated by OSHA, who has very specific guidelines as to how to minimize the potential spread of disease in the workplace. As audiologists, audiology technicians, hearing instrument specialists or students, our scope of practice dictates OSHA's jurisdiction; we are legally and ethically obligated to uphold these federally mandated infection control standards.

Despite the fact that a written infection control plan is a federal requirement, I often wonder how many of us have a written infection control plan in place that is readily accessible. Interestingly enough, Amlani conducted a survey in 1999 and asked practicing audiologists whether or not a written infection control plan was in place in their clinic. Less than half (44%) indicated that a written plan was in place, and more than half (51%) indicated that they did not have a written infection control plan in place. Burco (2007) repeated Amlani’s (1999) study and asked the same question to practicing audiologists. Interestingly, when this study was done, an overwhelming majority (86%) reported that they were indeed aware of a written infection control plan present in their clinic. In contrast to what Amlani (1999) found, none of Burco's (2007) respondents indicated “no,” whereas 14% indicated that they did not know. This was a huge change within a period of just less than 10 years. In my mind, it suggests one of two things. One is either that we have made great improvements in educating audiologists about infection control requirements so that infection control plans are being written and implemented, or two, that we are making improvements in educating audiologists about infection control requirements and we are simply getting better at knowing the correct answer. Whether or not this is truly happening is something that I do not know.

Most of you have indicated that you do have an infection control plan in your clinic, which pleases me, but the next step is to make sure that time we have a written one in place. The reason that I bring this up is because I received a phone call from a private practice individual about four years ago. They had participated in one of my infection control talks where we reviewed the need for a written infection control plan, and about six months after my course, OSHA showed up on their doorstep unannounced and inquired about their practice. The first thing they asked for was their written infection control plan. At that point, they did not have one and they were initially fined $5,000, but OSHA worked with them and gave them two weeks to get their plan together. Once they came back and saw the written infection control plan and audited their entire office, the fine was reduced to $500. Let me be clear that it is a requirement, and the reality of the situation is that there are fines associated with not having this document in place.

Requirements

As I have outlined, OSHA requires each facility to have a written infection control plan. This written plan is the cornerstone of all infection control programs. These are the six specific required sections per OSHA for a written infection control plan, as follows.

Section 1 addresses employee exposure classification. Section 2 addresses hepatitis B vaccination plans. Section 3 is a plan for annual training and records. Section 4 is the plan for accidents and accidental exposure and follow-up. Section 5 is implementation protocols, and section 6 refers to post-exposure plans and records

I am going to go over each of these sections, but we will just cover number one, two, three, four, and six very briefly. We will spend a significant portion of time of section five.

Employee Classification

Each employee must be classified into category that is based on the potential risk of exposure to blood and other infectious substances as a function of their professional responsibilities. A classification category must be assigned for each employee and documented in writing in the infection control plan. There are three classification categories to which employees may be assigned to. You are considered a Category 1 employee if your primary job responsibility exposes you to blood and bodily fluids. You are a Category 2 employee if your secondary job responsibilities potentially expose you to blood and/or bodily fluids. Finally, Category 3 means that no part of the job responsibility would expose an individual to blood or bodily fluids.

To put this in the perspective of the audiology clinic, an audiologist whose primary job responsibility is to conduct intraoperative monitoring or do postsurgical audiological assessments where patients may have oozing ears or open wounds would be categorized as a Category 1 employee. Most audiologists, as well as hearing instrument specialists, would be Category 2 employees, because their secondary job responsibility exposes them to blood and bodily fluids. We do handle hearing instruments. We do handle earmold impressions. Some of us are involved in cerumen management, which potentially exposes us to blood and other bodily fluids. Finally, Category 3 employees would be those audiologists who are in administration and do not have direct patient care; it can also include your front office staff that does not provide patient care.

Hepatitis B Vaccination

Employees who have the potential for encountering blood or other infectious substances must be offered the opportunity to receive a Hepatitis B vaccination (HBV). The HBV must be made available to all Category 1 and Category 2 workers free of charge by the employer. The employee does not have to accept the offer of a vaccination. However, a waiver must be signed noting that the Category 1 or Category 2 employee refused the offered vaccine. That has to be maintained in record within the infection control plan. The vaccination should also be administered by a trained medical professional and given in accordance to current medical standards as well.

Training

The third section is the plan for annual training and records. Each office is to conduct and document the completion of annual training in the infection control plan. Specifically, training must be provided during distinct times. Infection control training must occur at the time of initial assignment and must take place at least annually thereafter. While the standard does not specify the length of training, OSHA standards do list certain elements that must be included in the training program, which involves a lot of the material that I covered in Part One, including modes of disease transmission, information about an HBV, use of protective equipment, et cetera. Training is also required throughout the course of the year if there is an update or a new procedure that is being implemented in the clinic.

If you are starting to provide a completely new service, appropriate training must be conducted in a timely fashion to ensure that the new or updated procedure is understood and that you are performing that procedure in a manner that is consistent with minimizing the spread of disease. Additional training shall also be provided when changes such as modification of task or procedures affect the employees’ occupational exposure. For example, if you were a Category 3 employee and changed responsibilities that made you a Category 2 employee, it is a requirement for you to undergo infection control training. The established employees who change exposure classification categories should be trained within 90 days of hire or within 90 days of the change of their classification category. In all honesty, that training needs to be done before you take on your new responsibilities.

Accidental Exposure

All written infection control programs need to address a plan for accidents and accidental exposure and follow-up. Accidental exposures to blood-borne pathogens will require follow-up. While these may be relatively rare in the audiology clinic, an emergency plan needs to be created. As dictated by OSHA, if the exposure involves a percutaneous or mucous membrane exposure to blood or other bodily fluids or a cutaneous exposure to blood when the worker’s skin is chapped, abraded, et cetera, follow-up evaluations are required. The goal of this follow-up is to confirm that a disease has or has not been transferred, and in the event of a transfer, that the disease is treated effectively and efficiently.

Post-Exposure Plan

We are going to temporarily skip section five and go to section six, which is the post-exposure plan and requirement. The post-exposure plan and requirement addresses anything that happened in section four (Accidental Exposure) to make sure that follow-up has occurred in the event of the percutaneous exposure.

Implementation Protocols

Infection control templates are available to use as a guide, or you can take that infection control plan and use it word-for-word to create your plan. Sections one, two, three, four, and six can be copied, with the exception of your practice name, address and other clinic-specific information.

When it comes to the implementation protocols of section five, the content will differ significantly from one clinic to the next. Therefore, this section will be one you create on your own, because it will outline how you and your staff are going to execute the services that you provide based on your infection control philosophy. Because the content will be unique to your specific work environment, we need to spend more time dissecting implementation protocols. We are going to achieve that by simultaneously addressing the concept of work-practice controls, as well as the selection of appropriate infection control products.

The content appearing in the implementation protocols section of your infection control plan is going to be dictated by the scope of service that is provided by your clinic. As I addressed in Part One, to prepare to write the implementation protocols section of your infection control plan, the first thing you need to do is assess your scope of practice. This means making a comprehensive list of all the services offered by everyone on staff in your practice.

For example, if your clinic dispenses hearing instruments, you need to list every clinical procedure that falls under the umbrella of hearing aid dispensing. If you dispenses hearing aids, you most likely are involved in creating earmold impressions. You are most likely involved in the actual fitting. You probably are involved in doing some type of custom modifications. I am sure most of you perform listening checks. I hope most of us are performing real-ear measurements. Perhaps you have a loaner program for hearing instruments or assistive listening devices for patients who have hearing aids in for repair, or perhaps you have some sort of drop-off hearing aid service. Things like this should go on this list. It is critical to create this kind of list is because this will dictate how many work-practice controls you need to develop. A work-practice control is a profession-specific written procedure that outlines how you are going to perform a task which has been specifically designed to minimize the spread of disease.

Section five of the written infection control plan, the implementation protocols plan, is where you list your work-practice controls. For example, if your practice is involved in only four clinical tasks, your practice will be required to create four specific work-practice controls. One written procedure will outline how earmold impressions will be made in a manner that will minimize the spread of disease. Another one will address aspects of the hearing aid fitting. Another work-practice control will outline how hearing instrument modifications are going to be conducted in a manner that minimizes the potential spread of disease, and how a listening check is going to be performed in a manner that is consistent with infection control guidelines.

If you are a different hearing practice and offer verification and drop-off hearing aid services on top of those other services, you will now have to create six different work practice controls that address each of these different things. Once you do that, you have to take a look at everything that you provide in the clinic. Hearing aid dispensing is just one example. If you perform diagnostics, you need to create a list that indicates anything and everything that falls under those various umbrellas. If your clinic performs otoscopy, air conduction, bone conduction, and immittance testing only, then these are the four work-practice controls that you will make sure are in your written infection control plan. If you are a clinic that provides a more comprehensive diagnostic approach including vestibular and electrophysiological testing, you have to make sure that your written infection control plan includes all of these written procedures.

Up until this point, we have created an exhaustive list of services that are offered within your clinical setting. This dictates how many written work-practice controls that you have to create and insert in section five of your written infection control plan. It is important to understand that writing these work-practice controls is not an arbitrary task. As implied by its definition, the work-practice control must be written in a manner that outlines how a procedure will be performed that is consistent with minimizing the spread of disease. In other words, to ensure that the written procedure is consistent with infection control standards, the work-practice control must take into account any and all applicable guidelines that are outlined by the standard precautions.

Standard Precautions

Originally set in 1987 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), universal precautions was an initial list of recommendations that were specifically designed to protect healthcare workers from exposure to blood-borne pathogens at that time. These universal precautions were created as a direct response to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) outbreak. Since that time, the mindset of universal precautions was expanded beyond blood-borne pathogens, and it now includes any and all potentially infectious microorganisms, including the ones that are readily found throughout the clinical environment. Rather than hearing about universal precautions, these guidelines are more commonly referred to as standard precautions.

The standard precautions refer to a list of five guidelines issued by the CDC, which are intended to minimize the spread of potential disease in the healthcare setting (Figure 1).

Figure 1. List of the five standard precautions.

Appropriate personal barriers. I would like to address each guideline individually. Appropriate personal barriers must be worn when performing procedures that may expose you to infectious agents. Examples of standard personal barriers include things such as gloves, protective eyewear, disposable masks, a lab coat, apron, or maybe disposable gown.

Gloves are commonly used in the audiology clinic, and it is important to keep a few things in mind when investing in this type of product. Gloves are available in a variety of materials including nitrile, latex, and vinyl. One is not necessarily better than the other, but you need to keep in mind that many patients and clinicians have an allergy to latex. I am seeing more and more people go more towards vinyl or nitrile. In addition, glove size does matter. Gloves should fit tightly like second skin. There is really no such thing as one-size-fits-all, because gloves that are too large will interfere with dexterity and can cause accidents such as drops or spills. Likewise, gloves that are too small are not comfortable. You need to remember that you are a professional providing rehabilitative services. The only time you should be wearing a one-size-fits-all glove is if you are assembling deli sandwiches somewhere.

Within the confines of the audiology environment, there are many situations where gloves could be used. Gloves can be worn during certain times but not necessary during others. I will tell you that gloves must be worn when you are immersing or removing instruments from a cold sterilant because those are chemicals. In the event you are handling hearing instruments that have not yet been cleaned and disinfected, you need to be wearing gloves. You should seriously consider using gloves when you are removing and then subsequently handling an earmold impression from the ear. You should also wear gloves anytime that you or your patient exhibits visible wounds in areas that make direct or indirect contact with another person.

Safety glasses and/or disposable masks should be worn when using the buffing wheel during hearing aid or earmold modification procedures. Even if the hearing instrument or ear mold surface has been cleaned and disinfected, you still want to wear safety glasses and a mask, not only to avoid breathing in or making contact with any of the microbes that have been residing on the hearing instrument surfaces, but you want to protect yourself from breathing in or being exposed to particles that reside on the buffing wheel or grinding stones. Many of us do wear lab coats, but if you are an occasional or non-wearer, you really should be using a lab coat or some sort of disposable gown during these procedures, particularly when removing things from a cold bath or a sterilizing solution, because you do not want any of that liquid to spill on your clothes.

Hand hygiene. The second standard precaution refers to hand hygiene. Hand hygiene must be performed before and after every patient contact and after glove removal. The one thing I will tell you about hand hygiene is it represents the single most important procedure for effectively limiting the spread of disease. This, to me, is one of the most critical components of a basic infection control plan. Until recently, the only way that you were able to wash hands was with traditional soap and water. It is important to realize that the soap you use must be liquid, because bar soap is a breeding ground for germs. Medical grade soaps are recommended, because these maintain special emollients that are going to keep your hands from drying out. The thing that I will tell you is antimicrobial soaps really do not matter. If you have a preference to use antimicrobial soaps, go right ahead, but there is nothing magical about antimicrobial soaps.

Recently, the CDC and the American Medical Association (AMA) approved the use of no-rinse hand degermers as an alternative way to wash your hands, particularly when the clinician does not have access to a sink with running water. Those no-rinse hand degermers do meet the definition of performing hand hygiene. It is important for all of us to understand is nothing takes the place of traditional hand washing when you are using liquid soap and water. No-rinse hand degermers were most likely approved as an alternative simply because a lot of people in healthcare were not washing their hands. It was a matter of convenience. The no-rinse hand degermers are alcohol based and dry out the hands more readily. This potentially creates the issue of dry, chapped skin. In the event you come in direct contact with any form of contamination, it is necessary for you to wash your hands with soap and water. The no-rinse germers are not going to be as effective in addressing the specific issues associated with direct contact.

Hands must be washed at specific times throughout the course of the patient appointment, and the number of times that you are going to be washing your hands will depend on what it is that you are doing. Hands must be washed before and after every patient appointment. In addition, there are times during the appointment that you are going to have to wash your hands again based on what you are doing. Anytime during the patient appointment that you feel that you need to wash your hands, you should wash your hands. One of the requirements per OSHA is that any time you have performed a procedure in which you were wearing gloves, upon immediate removal of gloves, you must commence with hand hygiene procedures. Since the use of gloves suggests that you are performing some type of procedure that may potentially expose you to some sort of contamination, OSHA has made it a requirement. Even though there is a correct and safe way to remove gloves and dispose of them, the concern is that anything that has been on the outside of the glove may come in direct contact with your hands. This is why it is extremely important for you to wash your hands immediately upon removal of gloves.

Do we, as audiologists, wash our hands? Amlani (1999) posed the question, “Do you wash your hands either before or after each patient?” Only 26% indicated yes. “Do you wash your hands after using the bathroom?” Back in 1999, only 50% indicated yes, which meant that 50% of were not washing our hands after using the bathroom. Burco repeated this study in 2007 and asked the same questions. Thankfully, we have gotten better. Eighty-two percent indicated that they do wash their hands either before or after they see their patient, and 87% of us do wash hands after using the bathroom. The improvement looks great, but at the end of the day, there is no reason why we should not be seeing 100% in this case.

Disinfecting touch and splash surfaces. The third standard precaution is that touch and splash surfaces must be pre-cleaned and disinfected. There are several things that we need to define so we understand what this is. A touch surface refers to any area that comes in potential direct or indirect contact with the hands, and a splash surface is any area that may be hit with blood or other bodily secretions from a potentially contaminated source. In terms of terminology, the term “clean” simply refers to the removal of gross contamination. Germs are not necessarily killed; however, cleaning is an extremely important precursor to disinfecting and sterilizing. You need to clean something before you disinfect and sterilize it. In contrast, disinfection is a process whereby germs are killed, and the spectrum of the kill depends on the products that you are using.

Disinfection must be performed on touch and splash surfaces or on patient items that are not transferable to others. This is when we need to clean and this is when we need to disinfect. For example, after each patient appointment and prior to the next patient, touch and splash surfaces that need to be cleaned and then disinfected include things like horizontal surfaces such as a table, counter, armrest of a chair, the bone conduction vibrator, and the response button that is used during audiometric testing. Examples of other noncritical items that should be disinfected in between use include picks, loops, brushes that are specifically used to clean hearing instruments, pliers or nippers, as well as suction tips that are used to clean hearing instruments.

Disinfectants come in a variety of forms. Hospital-grade disinfectants these tend to be used by larger institutions because they offer some advantages. Hospital grade disinfectants are registered with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). When something is registered with the FDA, you will be able to obtain a kill sheet, which outlines the specific microorganisms that are killed. Hospital-grade disinfectants typically have a broader spectrum of kill than some of the household disinfectants. Some people, based on their infection control philosophy, want to go with hospital grade. We need to know that there are other disinfectants and cleaners that are not necessarily hospital grade, but are extremely effective in meeting the goals of your infection control plan.

I am always curious to see if people conceptually understand or can tell the difference between one term versus the other. Amlani (1999) asked audiologists the straightforward question, “Do you know the difference between the terms ‘clean’ and ‘disinfect?’” When asked that way, 74% of the respondents indicated that they know the difference between those two terms. He asked a second question which specifically forced them to identify the correct definition of both “clean” and “disinfect.” When it came to picking the right definition of “clean”, 73% picked the right definition, which tells me that those people who said they know the difference between “clean” and “disinfect” were right. When he asked those same people to correctly pick the definition of “disinfect,” only 55% got the answer right, which meant that about 20% of those people who thought they knew the definition did not. If I were to grade our performance on knowing the difference between “clean” and “disinfect” at that time, we were performing at a level of C- to F. Burco (2007) found, again, that there was an improvement in this area. About 78% of us can correctly define “clean” as well as “disinfect”. However, at the end of the day, we were still performing at a C+ level seven years ago.

Whether or not we know the definition of something is one thing, but it is important for us to make sure that we practice what we preach. Even if you do know the definition of these terms, Burco (2007) asked the question, “Do you clean and disinfect touch and splash surfaces after each patient?” Despite the fact that a lot of us know the definition of clean versus disinfect from a practical perspective, only about 50% of us are doing what we are supposed to be doing in terms of infection control. We are performing at an F level.

Sterilizing critical instruments. The fourth standard precaution is that critical instruments must be sterilized. A critical instrument is any reusable instrument that you introduce directly into the bloodstream, comes in contact with mucous membranes or bodily substances, or can potentially penetrate the skin from use or misuse. These critical instruments include such things as reusable cerumen management tools, reusable immittance probe tips, and reusable speculum. Critical instruments must be sterilized. We have already reviewed the definition of disinfect, which is a process whereby germs are killed. The term “sterilize” refers to a process whereby all germs are killed each and every single time. As a result of this definition, there are specific product requirements of which you need to be aware. There are certain products that you are going to have to use because they meet the definition of a sterilant. Sterilization must be performed on any reusable critical instruments that you intend to use with other patients.

Again, Amlani, back in 1999, found that the majority of us did know. Burco (2007) essentially found the same thing - most of us do know what sterilization means. We are performing at an A- to a B+ level.

There are many different ways that you can sterilize something, but the most common method occurring in the audiology clinic is cold sterilization. Cold sterilization involves sterilizing instruments by immersing them in chemicals for a specific amount of time. This requires investing in trays as well as in specific product. Only two ingredients that meet the definition of a cold sterilant have been approved by the EPA. Those are glutaraldehyde in concentrations of 2% or higher, as well as any product whose active ingredient is hydrogen peroxide in concentrations of 7.5%. When you invest in sterilants, you need to make sure you read the instructions, as how long you have to soak something in order to achieve sterilization will differ. Typically, glutaraldehyde-based products require a 10-hour soak, whereas hydrogen peroxide-based products require a 6-hour soak. You can use and reuse the same product in the tray up to a certain period of time. Glutaraldehyde-based products can be reused up to 28 days, whereas hydrogen peroxide products indicate reuse for 21 days.

Two very popular cold sterilants in the audiology field include Wavicide and Sporox. Once again, the instructions differ and you need to read the directions carefully. Wavicide is a glutaraldehyde-based solution whereas Sporox is hydrogen peroxide based. Some are available in gallon sizes. Some are available in quart sizes. Wavicide requires soaking for 10 hours to achieve sterilization. Sporox has a six-hour soaking time. Wavicide can be reused up to 28 days; Sporox is 21 days. Do not get those things confused. Read your labels.

Since we are using chemicals, I want to talk briefly about the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS). MSDS documents outline the hazards that are associated with chemical products. They outline composition and physical and chemical characteristics, but they also talk about precautionary measures that need to be taken, as well as first aid considerations in the event of a spill or accidental swallowing. If you have these chemical products in your clinic, it is your responsibility to have an MSDS on file. The MSDS does not necessarily come with the product when you order it. However, whomever you ordered it from should be able to provide you with an MSDS. If you have Sporox or glutaraldehyde in your practice, you must make sure that you have an MSDS on file because OSHA requires it.

From a practical perspective, a fair question that Burco (2007) asked was, “For those of you who are involved in cerumen management, do you clean and then sterilize your reusable cerumen management instruments?” The answer should be yes, and what he found was more than half the time people were not applying appropriate infection control procedures to such critical instruments. We are performing at an F level there.

The biggest confusion people seem to have is when to disinfect versus when to sterilize. A lot of people try to make it easier by simply going the disposable route. Instead of reusing items, they use disposable items, which are one-time-use only items that you throw out after use. The nice thing about that is there is no need to think about whether or not you need to clean and disinfect or clean and sterilize. You just toss it and you use the new one. It does eliminate many potential infection control errors that can occur as a result of human thinking. You would be amazed at what is disposable nowadays. Specula, headphone covers, electrodes, and ear tips for diagnostic equipment are disposable. There are a lot of new things that are completely disposable, including grinding caps, muslin buffs, and suction needles. Bite blocks are obviously disposable. Even in cerumen management, there are a variety of products that are inexpensive in the form of disposable curettes, loops, hooks, suction tubes, and forceps.

Whether or not you should take the disposable approach in your infection control plan is oftentimes an executive decision, and perhaps it is even a personal preference decision. It is important for you to take a look at what makes the most financial sense. You need to figure if it is cost-effective for you to use reusable versus disposables. Let’s look at a hypothetical example in Figure 2. Let's assume your clinic, on average, removes cerumen twice a day. You will be seeing 500 patients annually. You need to map out all the things in which you are going to have to invest from a reusable perspective and a disposable perspective to evaluate what makes more sense. The more cerumen you remove, perhaps the more it may make sense for you to invest in reusable. Again, the purpose of these was to do the math in order to figure out whether or not it makes financial sense.

Figure 2. Financial evaluation example to determine the cost effectiveness for reusable or disposable cerumen management tools.

Disposal of infectious waste. Finally, the last standard precaution is that infectious waste must be disposed of appropriately. With regard to audiology, most of the waste that we are going to deal with in the clinic can be disposed of in regular receptacles. The disposables that can cause injuries, such as blades, must be placed in a puncture resistant disposable container, called a sharps container. These are available in many different sizes. In the event that certain waste is contaminated with copious amounts of cerumen or blood, the material should be placed in a separate impermeable bag and then discarded in the regular trash. It is not necessary, nor are you going to be in that type of situation where you can be exposed to so much blood or cerumen, for you to worry about disposing of it in a different way.

To recap, five of the six requirements we talked about can be identical in everyone's infection control plan, whereas the implementation protocols are going to be very different, as they are clinic specific.

Putting it All Together

Let’s put this together so that you understand how to create your own work-practice controls. Work-practice controls are based on standard precautions. Let me demonstrate a technique that I use to create a work-practice control. Let's assume you are now going to be performing a hearing aid listening check. You have already washed your hands because you are already in the middle of the appointment. You are going to be handling a hearing aid, so you want to make sure you have some type of personal barrier. I am not going to worry about the hand hygiene. I will let that one go away. You will have to consider cleaning and disinfecting some things, because you are going to be handling hearing aids and using a stethoscope. In terms of cleaning and sterilization, you are not going to worry about it. Then in terms of infectious waste, you are probably going to be using some equipment that will end up being contaminated, which you will have to throw out.

By going through this procedure, I know that these are the three of the five standard precautions that I need to account for in my hearing aid listening check work-practice control. Whether you decide to accept a hearing aid with gloves, within a disinfectant towelette or to use a Dixie cup, you need to have some sort of personal barrier available such that you are not handling the hearing aids that has been removed from the patient’s ear with your bare hands. In terms of cleaning and disinfecting, we are going to have to make sure that we properly clean and disinfect not only the hearing instrument, but also the stethoscope bell as well as the earpieces, and we are going to have to make sure we throw things away to control for infectious waste.

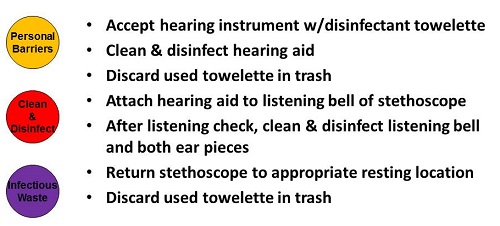

Figure 3 is an example of a perfectly acceptable work-practice control that is associated with the hearing aids listening check. We accept the hearing instrument with a disinfectant towelette. We are going to clean and then disinfect the hearing aid. We are going to discard the used towelette in the trash and then attach the hearing aid to the listening bell of the stethoscope. After we perform the listening check, we clean and disinfect the listening bell and both earpieces. Return the stethoscope to the appropriate resting location and then discard the used towelette in the trash. I am not providing a written procedure of how you do a listening check. This work-practice control shows this is how we are going to perform hearing aid listening checks in a manner that is consistent with minimizing the spread of disease.

Figure 3. Example of a hearing aid listening check work-practice control procedure.

The other important thing to realize is that everyone may have a different philosophy or approach of how they are going to perform a hearing aid listening check. For example, if your clinic feels strongly that you need to be wearing gloves during this procedure, you can write a hearing aid listening check work-practice control that takes into consideration the use of gloves, but since you are using gloves, you need to make sure that this specific work-practice control dictates that once you remove the gloves, you are going to discard them in the trash and immediately commence with hand hygiene procedures.

Resources

There are several resources available including Infection Control in the Audiology Clinic (Bankaitis & Kemp, 2004), which is a textbook that covers what you need to know, including implementation protocols with examples of written work-practice controls. In addition, my blog (aubankaitis.com) has weekly posts on a variety of topics, and there is a section on infection control.

Conclusion

The take-home message is that infection control is a required element of your practice. You need to create your written plan including the work-practice controls. Use standard precautions as your guide. Make sure you select and you use appropriate products. Implement this procedure. It is not good enough just to have a written plan; you have to practice what you preach and rely on your resources.

Questions and Answers

What disinfectant towelettes do you recommend?

If you are using disinfectant towelettes on littler things that are comprised of plastic, acrylic, or rubber or on hearing instruments, use something that is not alcohol-based, such as Audiologist’s Choice. Alcohol chemically denatures acrylic, rubber, silicone, and plastic. If you are doing bigger surfaces, whatever is the least expensive is the product that I would go with.

The front office person who takes walk-in patient hearing aids may do listening checks, change wax guards, and change batteries. Are they then considered a category 2 or category 3 employee?

A category 3 employee is any employee who does not have any type of patient contact or does not provide any types of services. Since this employee is providing a service, they would be categorized as category 2.

References

Amlani, A.M. (1999). Current trends and future needs for practices in audiologic infection control. Journal of the American Academy of Audiololgy, 10(3), 151-159.

Bankaitis, A.U. & Kemp, R.J. (2003). Infection Control in the Hearing Aid Clinic. Boulder, CO: Auban.

Bankaitis, A.U. & Kemp, R.J. (2004). Infection Control in the Audiology Clinic. Boulder, CO: Auban.

Burco, A. (2007). Current infection control trends in audiology, Paper 287. (Independent studies and capstones). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1277&context=pacs_capstones

Cite this content as:

Bankaitis, A. (2014, October). Infection control - what to do and how to do it. AudiologyOnline, Article 12953 Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com