Introduction

For more than 30 years an audiologist’s success has been predicated on her technical ability. Match the appropriate type of technology to a patient’s hearing loss, lifestyle and budget, ballpark the compression parameters to optimize audibility & comfort for various inputs, orient the patient toward initial use of the device, conduct probe microphone measures to verify a prescribed gain target, fine tune or tweak the device when complaints arise – do all these tasks and chances are good you will have a happy patient. Although each of these tasks is still vital to the long-term success of any patient, many of them can be replaced, or at the very least made more efficient, with smarter, faster, and more automated computer-based technology.

Audiologists now live in a world where an abundance of information about the patients’ preferences regarding hearing aid performance can be automatically fed back into the devices’ settings to render better sounding, individualized hearing aids. Thus, the audiologist can spend less time thinking about how to fine tune or tweak the hearing aid parameters and more time on other tasks germane to patient care. This new world order in which hearing aid technology continues to become more automatic and less expensive presents a myriad of challenges for audiology practices who historically have generated much of their revenue through the sale of devices. How will the profession of audiology survive in a world of self-guided tests and self-fitted hearing aids? The answer to this question rests primarily with audiology’s ability to connect at a deeper level with patients. The focus of this article is how audiologists can create value in the marketplace by transitioning away from their role as technology soldiers, firmly centered on the device, to a role in which true patient-focused care takes center stage. While technical knowledge of amplification devices and product innovation is necessary (there will never be a time when audiologist won’t need to know how to arrive at the proper compression kneepoints and ratios for a patient), their importance is less significant than the quality of the patient-provider relationship. In the end, it’s not extraordinary technology itself that matters, but how you apply that technology to evoke positive behavior changes in patients suffering from hearing loss. This article will address the role of trust between the provider and patient as the cornerstone to in-clinic success. Improve the level of trust among your patients and will create more advocates for your practice.

The Two Sides of Every Individual

In order to fully appreciate the role audiology plays in the marketplace, it’s important to embrace both sides of the equation shown in Figure 1. Individuals that seek out your services are both patients, often presenting with a chronic medical conditions requiring professional guidance, and customers who are making an elective decision to visit your practice, and pay at least a portion out-of-pocket for products and services.

Figure 1. The two sides of individuals seen for services in an audiology clinic.

Let’s first consider how customers view the world. Largely due to mass marketing, the Internet, social media and the ease in which information can be exchanged, we live in an era where consumer trust is quite low. Mistrust creates skeptical customers. Ironically, growing skepticism among customers is a normal and expected by-product of abundant information and exposure to the inner workings of the manufacturing process. A significant part of the audiologist’s role is to overcome this mistrust. The key is using the emotional impact of our dialogue with patients as a strategic advantage – an advantage that cannot be duplicated by other professions or ever-improving technology.

The other side of the individual in need of your services is that of patient. The term patient implies an individual who has a condition warranting the attention of a professional. In the vast majority of cases, patients seek an audiologist when their chronic condition requires on-going management over time, including the easing and elimination of social barriers that may impinge daily communication. Maybe because there is no physical pain, or because the emotional distress associated with an inability to communicate is bearable for many, patients are often reluctant or ambivalent about their hearing loss. Whatever the particular reasons, patients with endurable chronic conditions often demonstrate a constellation of behaviors such as avoidance, denial, vulnerability and ambivalence. Over the years, several studies have examined how adults with chronic medical conditions such as age-related hearing loss, manage their condition and what cues to action may influence their behavior change. Various models have been proposed to explain the process of how adult patients cope with hearing loss (See Saunders, Chisolm, & Wallhagen, 2012; Laplante-Levesque, et al., 2012 for a review).

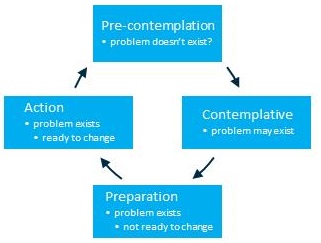

The transtheoretical stages of change model has been used to describe how adults with hearing loss cope with their condition. This “stages of change” model suggests that an individual’s ability to change passes through four distinct levels, summarized in Figure 1. These levels are best summarized as: a) pre-contemplation, at which time the individual cannot even consider acknowledging a problem exists and that behavior change is needed; b) contemplation, at which time individuals are ambivalent about the existence of a problem and the need to change behaviors; c) preparation, at which time an individual is preparing to make changes by seeking information and talking about this possible change with others; and d) action, during which time individuals make actual changes to their behaviors. The literature also mentions a fifth stage, called maintenance, at which time the individual makes a deliberate attempt to maintain their changed behaviors.

Figure 2. Stages of change model.

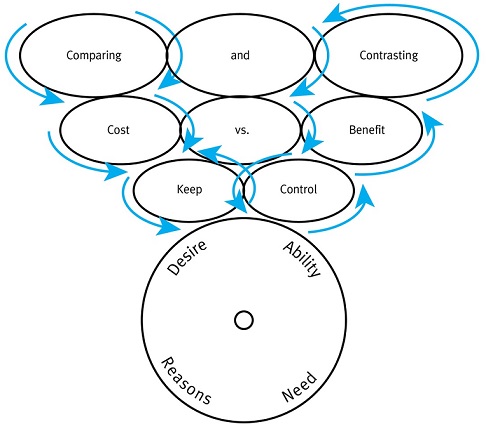

A similar model proposed by Carson (2005) attempts to explain the underlying decision-making process of hearing impaired individuals. The Spiral of Decision Making model explains the “push-pull” between seeking help and not seeking help that many patients with gradual onset hearing loss experience. Carson based this model on a longitudinal study of a group of woman between 72 and 82 years of age. Her model, summarized in Figure 2, suggests that individuals with gradual hearing loss evaluate, analyze and make decisions around three themes that define self-assessment: comparing/contrasting, cost vs. benefit, and control. Carson’s model proposes that this spiral of decision making is ongoing, even after remediation and treatment of the hearing loss, and may manifest itself in unpredictable ways. Patients take information they’ve received or assembled over time about their hearing loss and apply it anew to another round of self-assessing. However, when they go through this next round of self-assessing they are at a new place of understanding, further along the trajectory of coming to terms with their hearing loss. Patients involved in the Spiral of Decision Making process are likely to be searching for a professional they have faith in, believe in or trust. How poised are audiologists to become a patient’s “trusted advisor?”

Figure 3. The Spiral of Decision Making and Patient Behavior Change, based on Carson, 2005. Desire, ability, reasons and need are the components of individual behavior change.

The Principal-Agent Dilemma

When one individual is reliant on the guidance or input of another person, trust is at the heart of the interaction. Imagine a world without trust: Even the smallest decisions in daily life become unbearably burdensome. Trust is the engine that keeps society humming. Patrick Lencioni, the author of the popular business book, The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, placed vulnerability-based trust at the very foundation of his five core traits of an effective team. Vulnerability-based trust is defined as the ability of teams to be transparent and honest with one another in moments of weakness. Without trust nothing much would ever get done.

At the very core of trust resides something called the principal-agent dilemma. The principal-agent dilemma may occur when there is asymmetrical information between two parties involved in a professional relationship (Stiglitz, 1987). This situation, in which one party is acknowledged as the expert, and the other party knows considerably less about the condition, is known as asymmetrical information. In an audiology practice, asymmetrical information exists between the patient (principal), who often wonders whether the audiologist (agent) is recommending expensive treatment of their handicapping condition because it is truly necessary for the patient, or because the recommendation is likely to generate income for the audiologist. Social scientists have associated the principal-agent dilemma with a myriad of professions, including dentistry, law and medicine. Patients have preconceived expectations about the quality of care or service they may receive. These expectations and attitudes have been formulated over time through exposure to advertising, direct experiences with a profession and word-of-mouth chatter with other persons. The degree of trust between the patient and professional during the early stages of an appointment is framed by these initial expectations.

Trust is the elixir of the principal-agent dilemma. Situations with asymmetrical information put the burden of promoting trust on the professional. The central feature of trust is the patient’s belief that the audiologist will put the patient’s interests first. When the level of trust between the patient and audiologist is high, the overall quality of care the patient receives and the success of the clinic are likely to be high. In contrast, when trust between the patient and audiologist is low, benefit, satisfaction, and even adherence to the recommendation is likely to be poor.

The Role of Trust

Because of the principal-agent dilemma, the ability to engender a trusting relationship is a fundamental challenge of the patient-audiologist relationship. Before we discuss how trust can be enhanced, it may be helpful to define trust and its role in the healthcare care delivery process. The medical literature is replete with definitions of trust. Trust is a multifaceted quality that core characteristics such as competence, fidelity, honesty, compassion, and confidentiality. These traits are fundamental to success as a healthcare provider. Additionally, there are qualities of trust that are associated with the institution of delivering care, rather than the individual. Attributes of institutional trust include a patient’s attitude and beliefs about the clinic, insurance company and profession.

From the patient’s point of view, trust is built on a healthcare professional’s interpersonal competence (Mechanic & Meyer, 2000) and institutional trust (LaVeist, Nickerson, & Bowie, 2000). Behaviors that have been shown to promote trust in healthcare services include: dependability, being respectful and forthright with patients, communicating clearly, and thoroughly evaluating problems (Thom, 2001). Given all the changes in the healthcare system, along with the sheer abundance of information available to patients via the web, there is growing concern that trust is waning. Therefore, it’s critical to examine trust more closely and determine how it can be improved in order for the patient-audiologist relationship to flourish.

A review of the medical literature, summarized by McKinstry and colleagues (2006) indicates that trust in the healthcare setting has the following key characteristics:

- Trust is fluid. A patient’s perception of trust can change quickly or gradually over time.

- Trust develops over repeated visits.

- The primary driver of trust is the quality of the patient-provider relationship.

- The level of perceived trust can be charted on a continuum from high to low.

- Mistrust and low trust are not the same.

- Trust is based on expectations of what will happen in the future relative to prior experiences.

Specifically, trust is interconnected to three aspects of service delivery that warrant further consideration: adherence to recommendations, patient satisfaction, and continuity of care.

Patients who define their relationship with their audiologist as one of “high trust” are likely to follow the audiologist’s recommendation more then 90% of the time, while those who classify their relationship with the audiologist as one of “low trust”, follow the recommendation about 50% of the time (English & Kasewurm, 2012).

Trust and patient satisfaction are intricately connected. Although closely related, satisfaction and trust are distinguishable from one another (Hall, Dugan, Balkrishnan, & Bradley, 2002). It has been posited that trust develops over repeated visits, and satisfaction revolves around the services already received. Thom (2001) indicates that trust is based on the quality of the provider-patient relationship, while satisfaction is determined by the service delivery process. On the other hand, English & Kasewurm (2012) suggest that satisfaction with service promotes trust. Generally, satisfaction is related to a specific transaction or appointment, while trust is more closely connected with the quality of the relationship with a specific individual. Although both trust and satisfaction are integral to your in-clinic success, a high trust relationship is a springboard for improved satisfaction and hearing aid benefit.

Trust improves continuity of care. Continuity of care is concerned with the quality of care over time. Gulliford, Naithani, & Morgan (2006) propose that continuity of care is idealized in the patient's experience of a 'continuous caring relationship' with a specific healthcare professional. For providers in large multispecialty medical centers, the contrasting ideal is the delivery of a 'seamless service experience' through integration, coordination and the sharing of information between different providers. From the patient’s perspective, continuity of care relates to both the interpersonal aspects of care and the coordination of that care. According to Pandhi, Bowers, & Chen (2007), patients who described their relationship with their physician as comfortable were more likely to experience a higher level of trust.

Promoting Trust

The interconnectedness of these aspects of the service delivery process with trust warrant the question: If the level of trust between patient and audiologist can be promoted, will it lead to better patient outcomes? If we agree that trust is a foundation for more successful patient and business outcomes, then audiologists and their staffs need more concrete strategies for promoting trust with their patients.

In his book, The Language of Trust, Maslansky offers a step-by-step strategy for "credible communication." Four messaging principles are key to his approach: be personal, plainspoken, positive, and plausible. These principle messages are centered around the act of listening to customers and prioritizing their interests. These 4-Ps of trust provide a foundation for how professionals can become better communicators with their patients. Let’s examine each of these principles and how they might create greater levels of trust with patients.

Be Personal. When hearing aid technology is the primary focus of the dialogue between a patient and audiologist, it is easy to fall into the trap of talking too much about what we have to offer or what the individual might need. The pitfall with this approach is that focusing too much on what we have and not enough attention on what they want is likely to diminish trust. In this scenario our language becomes internally focused and is likely to result in the individual experiencing a sense of mistrust. By thinking about the situation from the point of view of the individual with hearing loss, you are more likely to engage in dialogue that is externally focused. Thus we need to tailor the dialogue to better meet every individual’s unique needs.

Be Plainspoken. The more you can personalize the dialogue by using simple and direct language, the more likely you are to promote high levels of trust. When the opportunity to discuss hearing aid technology and other technical issues arise, then the use of clear, straightforward terms rather than jargon is likely to create trust.

Be Positive. According to Alcock (2014), people are more likely to become engaged in positive behavior change when given an affirmative reason to change their behavior. Part of using positive triggers to action requires the audiologist to use language that places doing something about hearing loss in a favorable light, rather than a condition to be avoided. When audiologists talk about all the positive attributes associated with good communication, mistrust is more likely to be avoided.

Be Plausible. One of the hallmarks of a skeptical person is his ability to not be bamboozled by overhyped products. Audiologists must be careful to not overstate potential hearing aid benefits, or to rely on arcane jargon to describe amplification features. By transparently discussing the advantages and limitations of potential management options while avoiding the use of superlative terms, audiologists are more likely to apply Maslansky’s language of trust.

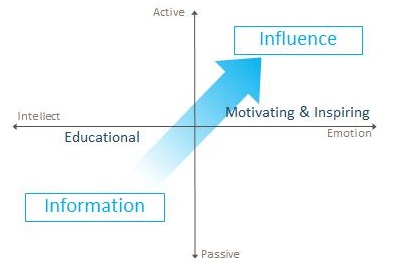

Another strategy for engendering higher levels of trust is outlined in Figure 4. The main idea shown here is that audiologists must find ways to transform an interaction that is information-laden to one that is more likely to influence the patient’s decision to accept your guidance and support. When you dissect the patient-audiologist interaction along two continuums: Content of the Message (intellectual to emotional) and Involvement of the Patient (Passive to Active) you begin to see opportunities for inspiring the patient into behavior change. Audiologists are encouraged to use all manner of visual aids and props to move from a message centered on patient education to one that motivates and inspires patients to make positive change.

Figure 4. Active communication matrix.

The Mindset of Trust

In November 2014, Gallup's annual survey announced that nurses had been voted the most trusted profession in America. According to the press release, 81% of Americans believe nurses' honesty and ethical standards are either "high" or "very high." Notable is the fact that nurses were voted the most trusted profession in the U.S for 14 of the past 15 years. Nurses, of course, work closely over an extended period of time with patients, often in perilous situations, and, rarely, if ever, have to ask patients to pay a bill. On the other hand, audiologists conduct sophisticated procedures in a medical setting where patients oftentimes have to pay out of pocket. How might this unique circumstance affect trust? Preminger and colleagues (2015) systematically evaluated how trust is promoted in adults with hearing loss who visited a clinic. The researchers interviewed 29 adults from four different countries. Their results showed that patients enter into the clinic with a preconceived level of trust that varies from low to high. They found that trust continues to evolve rather than remain static, and that both the patient and the provider can foster greater bonds of trust. Furthermore, the researchers found that trust diminished when the provider used a commercialized approach with a focus on sales instead of service.

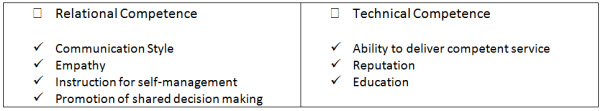

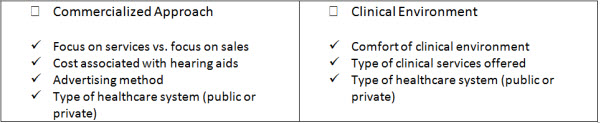

Perhaps the most actionable part of this study is the authors’ creation of a multidimensional model of trust. These dimensions are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Note that trust is assigned to both the clinician (Table 1: Interpersonal Trust) and the clinic (Table 2: Institutional Trust). Within each of these two designations are four discrete components of trust: relational competence, technical competence, commercialized approach and clinical environment. Each component has several kinds of activities or items that are part of promoting trust.

Table 1. Components of Interpersonal Trust (Preminger, Oxenboll, Barnett, Jensen, & Laplante-Levesque, 2015)

Table 2. Components of Institutional Trust (Preminger, Oxenboll, Barnett, Jensen, & Laplante-Levesque, 2015).

The components in Table 1 and 2 provide audiologists with a structure for viewing trust from the patient’s perspective. It is conceivable that audiologists could improve the level of trust with their patients by improving their communication style, by expressing greater empathy, and by getting patients more involved in the decision making process. With respect to institutional trust, business managers, clinicians and front office staff could work together to promote higher levels of trust by easing the perception of a commercialized approach. This could be accomplished by providing more services that complement the sale of hearing aids, creating a more comfortable clinical setting and modifying marketing messages to make them less price-driven and product-focused. Putting these concepts into action requires a mindset of trust.

Lastly, Preminger et al.’s (2015) research offers audiologists insight on how trust can be promoted and how it sometimes becomes derailed. It reinforces the fact that trust is fluid and evolves over time. Each time you are face-to-face with a patient is an opportunity to either enhance or diminish trust. And, change in a patient’s perception of trust is relative to their past service experiences and current expectations. Using this vein of research as a guidepost, audiologists have the ability to foster more trusting relationships with their patients by being mindful the following:

Avoid a focus on the transactional hearing aid sales process

- Provide comprehensive services, including rehabilitative services

- Use tools and procedures that contribute to a shared decision-making process. See Cox (2014) for a summary of decision-making tools.

- Display, perhaps even flaunt, your technical competence

- Provide a comfortable, professional workplace environment

- Be cognizant of the consistency of care you provide

- Practice effective, empathic communication

Drawing on the previously cited work of Maslansky (2010), a cornerstone of promoting a more trusting relationship with patients starts with the audiologist’s ability to practice good communication skills. Good communication skills are comprised of your ability to engage the patient by trying to understand their perspective, and finding common ground where the patient is comfortable discussing their unique situation. Once you’ve engaged the patient in dialogue, focus on the patient’s interests, share honest concerns, and expose your own vulnerabilities. Building trust is a process that requires audiologists to take the focus away from the transaction of selling a product. Instead, it requires audiologists to focus squarely on being effective counselors that move people through the various stages of change. In an age where technology is ever-improving, your in-clinic success is predicated on your ability to promote trust with the two sides of every individual: skeptical consumer and spiraling patient.

References

Alcock, C. (2014). Trigger happy hearing: Using social triggers to promote regular hearing checks. Audiology Practices,6(2), 8-15.

Carson, A.J. (2005). “What brings you here today?” The role of self-assessment in help-seeking for age-related hearing loss. Journal of Aging Studies, 19(2), 185-200.

Cox, R. (2014, April). 20Q: Hearing aid provision and the challenge of change. AudiologyOnline, Article 12596. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com

English, K. & Kasewurm, G. (2012). Audiology and patient trust. Audiology Today, 24(2), 33-38.

Gulliford, M., Naithani, S., and Morgan, M. (2006). What is 'continuity of care'? Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 11(4), 248-50.

Hall, M.A., Dugan, E., Balkrishnan, R., & Bradley, D. (2002). How disclosing HMO physician incentives affects trust. Health Affairs, 21(2), 197-206.

Laplante-Levesque, A., Knudsen, L.V., Preminger, J.E., Jones, L., Nielsen, C., Oberg, M.,…Kramer, S.E. (2012). Hearing help-seeking behavior and rehabilitation: Perspectives of adults with hearing impairment. International Journal of Audiology, 51(3), 93-102.

LaVeist, T.A., Nickerson, K.J., and Bowie, J.V. (2000). Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Medical Care Research & Review, 57 (Suppl 1), 146-161.

Lencioni, P. (2012). The Five dysfunctions of a team, 2nd edition. New Jersey: John A. Wiley & Sons.

Maslansky, M. (2010). The Language of trust: Selling ideas in a world of skeptics. New York: Prentice Hall Press.

McKinstry, B., Ashcroft, R.E., Car, J., Freeman, G.K., and Sheikh, A. (2006). Interventions for improving patients’ trust in doctors and groups of doctors. Cochrane Database System Review, 19(3). CD004134

Mechanic, D., & Meyer, S. (2000). Concepts of trust among patients with serious illness. Social Science & Medicine, 51(5), 657-658.

Pandhi, N., Bowers, B., & Chen, F.P. (2007). A comfortable relationship: A patient-derived dimension of ongoing care. Family Medicine, 39(4), 266-273.

Preminger, J.E., Oxenboll, M., Barnett, M.B., Jensen, L.D., & Laplante-Levesque, A. (2015). Perceptions of adults with hearing impairment regarding the promotion of trust in hearing healthcare service delivery. International Journal of Audiology, 54(1), 20-28.

Saunders, G.H., Chisolm, T.H., & Wallhagen, M.I. (2012). Older adults and hearing help-seeking behaviors. American Journal of Audiology, 21(2), 331-337.

Stiglitz, J. (1987). Principal and agent: A dictionary of economics. The New Palgrave: New York.

Thom, D.H. (2001). Physician behaviors that predict trust. Journal of Family Practice, 50(4), 323-328.

Cite this Content as:

Taylor, B. (2015, January). In-clinic success: using trust to create advocates in a world of skeptics. AudiologyOnline, Article 13178. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.