Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Describe the utility of hearing-aid TeleCare services.

- Describe the benefits of TeleCare for the hearing aid users regarding their important communication situations.

- Describe the benefits of TeleCare as it relates to burden for the caregiver.

Introduction

Due to the slow progression of age-related hearing loss, its impact is often overlooked and underestimated. Adjusting to and accepting a hearing loss later in life leads to more psychological trauma than developing a hearing loss early in life because later in life the patient has developed a personality and lifestyle based on his or her hearing ability (Sebastian, Varghese, & Gowri, 2015). One significant area that is affected by age-related hearing loss is quality of life. Quality of life should be viewed as multidimensional and can include but is not limited to factors such as physical, material, social, and emotional well-being. Hearing loss has been shown to lead to a decline or reduction in all of those areas (Dawes et al, 2015). Moreover, having to exert extra concentration on attempting to hear a message can lead to increased effort and fatigue.The patient may also need to rely on community or family support to understand the message, resulting in decreased independence and a higher likelihood of social isolation.

Participation in social activities is known to be related to good cognition, but social activities are often times compromised by hearing loss. There has been evidence that hearing loss in the elderly correlates with the development of cognitive decline earlier and more often than in non-hearing impaired individuals (Lin et al., 2013). Hearing loss can cause a decline in cognition in two ways: reduced auditory input causes reduced cognitive demand and leads to a general decline in function. Additionally, reduced auditory input may divert brain activity to communication demands, which can then lead to mental fatigue for other tasks (Cherko et al., 2016). Therefore, it is likely that hearing loss directly affects cognition via impoverished sensory input and indirectly through a decrease in socialization (Weinstein, 2017).

The detrimental effects of hearing loss can extend to other people in the elderly patient’s life, especially significant others and care givers. When compared to other medical condition, such as cognitive decline, the patient and family may see the other medical condition as more important than treating the hearing loss. Unmanaged hearing loss can have a negative impact on other conditions and lead to problem behaviors that may be similar to those seen with cognitive impairment, such as repetitive questioning, arguments, and activity disturbances. Interaction between the patient and their significant other or caregiver may be hindered due to the resulting communication deficits and breakdown, leading to frustration and a lesser desire to communicate. A patient’s significant others or care giver may actually benefit from the use of the hearing aid more than the individual with the hearing loss because communication will then become a less stressful and anxious, making it a more enjoyable experience overall. (Palmer et al, 1998).

Although the term dementia is no longer in the Diagnostic Manual for Psychiatric Disorders Volume 5 (DSM5), it is still a commonly used term to describe cognitive concerns in the aging population. The development of dementia is a process of steady cognitive decline. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a transitional stage between normal aging and dementia, characterized by the presence of cognitive impairment that does not necessarily interfere with activities of daily living (Peterson et al, 1999). Symptoms may include mild problems with memory, language, and cognitive processing. The estimated prevalence of MCI is 10-20% in adults aged 65 and older (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012).

People with MCI by definition may not require care, but family members or friends often take over the more complex instrumental activities of daily living or support the person regularly. Caregiver burden is a term that typically describes the emotional burden experienced by informal caregivers (Lynch & Lobo, 2012). In a study comparing the rates of caregiver burden among caregivers of participants with MCI and a control group, 36% of caregivers reported clinically significant levels of burden, which was twice that of the control group (Paradise et al., 2015). Some of the stress causing caregiver burden may be related to decreased functional independence or the behavioral disturbances evidenced in the person with MCI they are caring for (Hall et al., 2014). Caregiver burden is not only associated with an adverse emotional state and psychiatric morbidity, but can have a negative impact on the physical, financial, and social aspects of their life as well (Paradise et al., 2015). The caregiver may feel isolated from their larger social network and have their sense of self threatened as they notice themselves losing patience and becoming angry at the person they are caring for with MCI (Blieszner & Roberto, 2010).

One area where the caregiver burden can exist is related to the recipient’s use of hearing aids, especially for a new hearing aid user. On average, new hearing aid users require 3-4 office visits; maybe more visits if considerable fine-tuning is needed, or if physical fit issues exist. When cognitive problems are present, extra time often also is needed for training regarding the use and care of the hearing aids. In many cases, the caregiver is not only responsible for assisting in the day-to-day use and adjustment of hearing aids, but also must assist the patient in getting to and from the necessary appointments.

Today, many of these issues can be handled through teleaudiology, more specifically hearing aid telecare software such as Signia TeleCare. TeleCare is an umbrella term to describe the provision of hearing healthcare services from a distance by using modern telecommunication systems including wireless communication. Through TeleCare, hearing care providers (HCPs) can reach out to the patients, reduce barriers, make programming changes to the hearing aids, improve user satisfaction, and help avoid patients having to travel or be transported to receive high quality hearing-related care. TeleCare can benefit the patient by allowing problems to be solved in a timely matter. And, related to our discussion here, TeleCare also can be very useful for the caregiver of someone with dementia who uses hearing aids.

The specific features of Signia TeleCare include:

- The ability to remotely monitor indicators such as wearing time, program use, and situation classification to determine when intervention might be necessary.

- Ability to track the patient’s satisfaction for different real-world listening conditions to determine if programming changes or additional counseling is warranted.

- The option to deliver at-home patient care by solving issues after the initial fitting through remote programming changes to the gain, output, frequency response, noise reduction and other algorithms.

- Real-time video calls as well as text and voice CareChat capabilities enable easy and direct communication between the HCP and the patient.

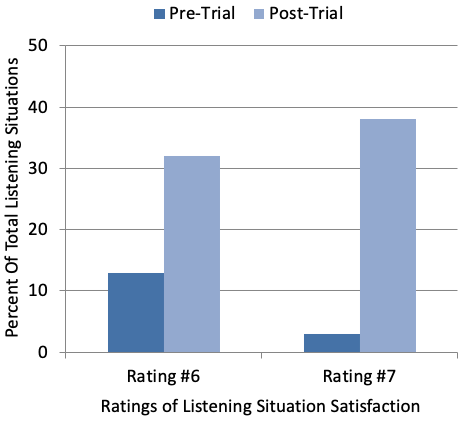

Previous studies with Signia TeleCare have been encouraging. In independent research conducted at the University of Western Ontario, participants using hearing aids rated their communication ability for several self-selected communication settings (Froehlich, Branda, & Apel, 2018). The ratings were conducted both before and then again after a home trial. During the home trial, the participants used Telecare, and completed satisfaction ratings for each listening condition. One aspect of the research centered on the number of situations where the participant was either Very Satisfied or Extremely Satisfied with the performance of the hearing aids. The results of this are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Satisfaction ratings for 60 different listening situations were obtained Pre-Home Trial and Post Home Trial, and based on a seven-point Satisfaction Scale (1=Extremely Dissatisfied and 7=Extremely Satisfied). Shown here are the percent of ratings that were either a #6 (Very Satisfied) or #7 (Extremely Satisfied). Modified from Froehlich, Branda and Apel, 2018.

Prior to the home trial, 13% of the situations received a rating of Very Satisfied, and only 3% a rating of Extremely Satisfied. Following the home trial with TeleCare intervention, 32% and 38% of situations received a rating of Very Satisfied and Extremely Satisfied respectively. That is, 70% of the combined 60 situations received a highly satisfied rating; importantly, 23 (38%) of these 60 situations involved speech understanding in background noise.

Given the known advantages of TeleCare for patients using hearing aids, we questioned if caregivers also would embrace the use of this feature, and if it might reduce the stress and burden for caregivers who are attending to MCI or dementia patients who have been fitted with hearing aids for the first time. Additionally, we questioned if the use of TeleCare resulted in improved communication for the MCI or dementia patient, as reported by the caregiver.

Clinical Study

Research was conducted at the University of South Dakota Speech, Language, and Hearing Department. Participants were recruited through clinical records and notices at various local facilities. Primary inclusion requirements were a bilateral hearing loss severe enough to warrant amplification, a desire to use hearing aids but not a previous consistent user, a score below 28 on the education-corrected Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), but still had their own power of attorney. Each individual also had to have a caregiver willing to participate in the study who was skilled in using a compatible smart phone to operate the Signia TeleCare.

The resulting participants (hearing aid users) were 20 individuals age 62 to 84 (mean age 72 years); 19 males and one female. The caregivers ranged in age from 54 to 77 (mean age 65 years); 19 females and 1 male. All participants had bilateral downward sloping hearing losses, with the mean audiogram showing hearing loss ranging from 20-25 dB in the low frequencies (250, 500 Hz) dropping to 60-65 dB in the high frequencies (6000, 8000 Hz). Their mean education-corrected MMSE ranged from 23 to 27 with a mean of 25.

All participants were new hearing aid users and were fitted bilaterally with the Signia Pure Nx using click sleeve coupling appropriate for their hearing loss. The hearing aids were programmed using the Signia Connexx 8.4 software to NAL-NL2 adult prescriptive targets, verified with probe-microphone measures for soft, moderate, and loud inputs to ensure comfort and audibility. All directional and noise reduction features were activated. The Client was enabled in Signia TeleCare via the Connexx software. The myHearing app was downloaded to the caregiver’s smartphone from GooglePlay or the Apple App Store and paired to the hearing aids prior to leaving the fitting appointment. Research staff had access to TeleCare at the Signia Internet portal (https://telecare.signiausa.com/#/login). The portal was checked throughout the work week for messages from the caregiver. Counselling through “Messages” was conducted, and remote fine tuning adjustments through “Remote Tuning” were completed when needed.

A cross-over design was used, with individuals randomly assigned to one of two equal groups, which included a total of six weeks of hearing aid use. Group 1 received TeleCare for the first three weeks, but not the last three weeks. Group 2 was not informed of TeleCare for the first three weeks, and then used TeleCare for the final three weeks of their trial. During the three-week period when the participants were not using TeleCare, they were scheduled for an in-person follow-up clinic visit, along with their caregiver, mid-way through the three week trial. All participants and caregivers returned to the clinic at the end of the six week home trial. In total, all participants and caregivers made four visits scheduled visits to the University Clinic.

As mentioned earlier, the task of bringing patients with cognitive concerns to medical appointments can be a burden for caregivers. The University of South Dakota is located in a small University town, with minimal traffic and parking issues. However, because of the rural nature of the location, it was necessary for many of the participants to travel a considerable distance for their clinic visit. On average, this distance was 37 miles, with some traveling from a distance of 100 miles or more.

At the time of the initial fitting, using a COSI format (Dillon, James & Ginis, 1997), each caregiver was asked to nominate three listening situations that they believed were important for the participant, and where they would want to see improvement using hearing aids. At the end of the first three weeks of hearing aid use, the cross-over point, all participants and caregivers returned to the clinic, and the caregivers completed three scales:

- The COSI scale of the three nominated communication items, rated in the conventional 5-point COSI format: 1=Worse to 5=Much Better.

- A behavioral change scale, scored in the same manner as the COSI. This scale was based on the findings of Palmer et al (1998), in their research involving the use of hearing aids with patients with dementia. Five behavioral characteristic were assessed: engage in conversations, engage in interactions, more aware of environmental sounds, paying attention to TV, and general alertness.

- An 11-question burden scale also was administered, using a 5-point rating scale (1=minimal burden to 5=significant burden). Some of the items of this scale were adapted from the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (Blieszner & Roberto, 2010).

At the end of the study (6-weeks of hearing aid use) the caregivers returned to the clinic and again completed the three scales above, and also a fourth scale consisting of three questions related to their satisfaction regarding the use of TeleCare (7-point scale; 1=Significantly Disagree, 4=Neutral, 7=Significantly Agree).

Study Findings

This was a 6-week cross-over design regarding the use of Signia TeleCare—both groups used TeleCare for three weeks, and were without TeleCare for three weeks. Caregivers completed three different scales which examined: the benefit obtained by the participants for the three COSI communication items selected by the caregivers, behavioral changes of the participants while using hearing aids, and ratings of burden by the caregiver relative to their care of the participant adjusting to hearing aid use. Portions of these data were reported previously by Jorgensen, Van Gerpen, Powers, & Apel (2019).

COSI Ratings

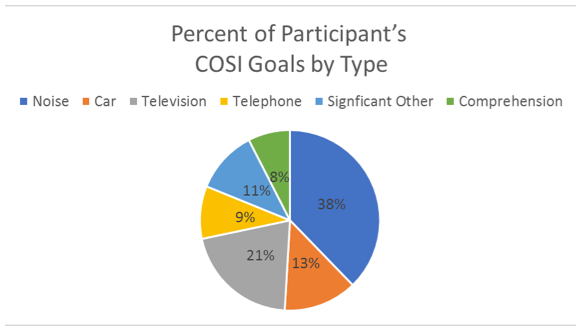

To facilitate the analysis of the nominated COSI items (total items=60; three from the caregiver of each participant), the items were grouped into six different categories: speech understanding in background noise, in the car, listening to television, on the phone, with significant others, and a general category including goals related to overall comprehension (e.g., not saying “what” all the time). The distribution for the different categories is shown in Figure 2. As might be expected, a large percent (38%) of the listening situation involved background noise, with listening to TV the second most common (21%).

Figure 2. The 60 nominated COSI listening situations grouped into six general categories, with percentage of items for each category displayed.

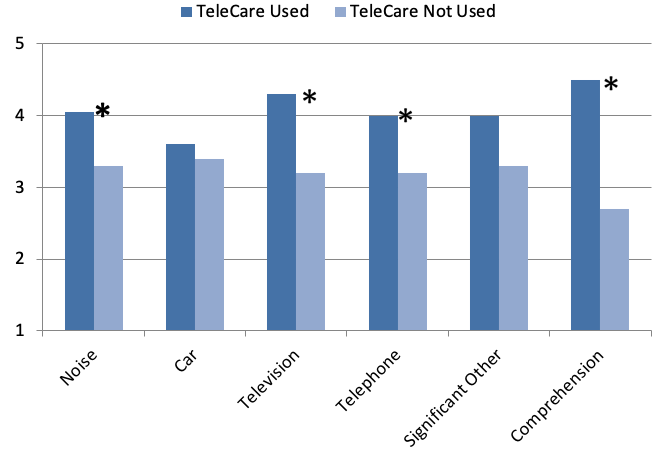

Shown in Figure 3 are the mean COSI ratings (by the caregiver) for the period of TeleCare use vs. when TeleCare was not used. As shown, the overall ratings for the COSI items revealed a general trend toward improvement when using hearing aids. Regardless if TeleCare was used, most all categorical mean ratings were at 3.0 or higher (#3 rating= Somewhat Better). What stands out, however, is the difference when TeleCare was part of the post-fitting treatment plan. The benefit derived from TeleCare was present for all categories, and significant for four of the six (p<.05). For many of the categories, the difference in mean performance was quite substantial, with the greatest difference for general comprehension, where the average rating was 4.5 when TeleCare was applied vs. only 2.7 when it was not.

Figure 3. Displayed are the mean COSI ratings (completed by the caregiver) regarding the participants’ performance for a given three-week period. Mean values for TeleCare use versus when TeleCare was not used are shown. Ratings conducted using a 5-point scale: 1=Worse, 2=No Difference, 3=Slightly Better, 4=Better, 5=Much Better. The 60 COSI items provided by the caregivers were categorized into six areas (see Figure 2). Significant differences (p<.05) between the TeleCare condition are denoted by an asterisk (Adapted from Jorgensen, Van Gerpen, Powers, & Apel, 2019).

Changes in General Behavior

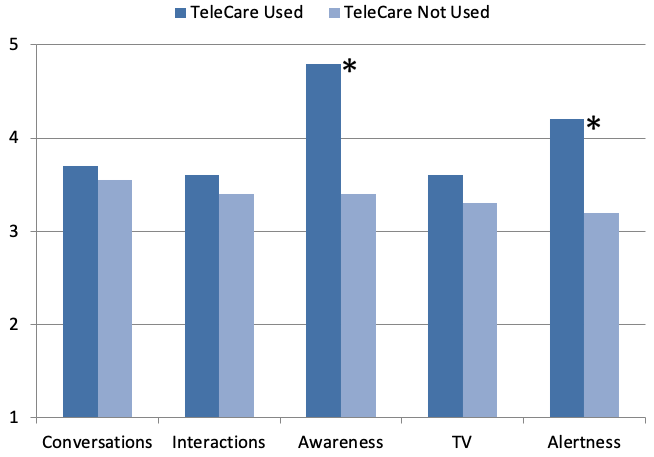

In a 1999 publication related to hearing aid use with patients with dementia, Palmer and colleagues (1998) reported that caregivers cited many positive changes that occurred when patients with dementia began using hearing aids. We used these comments to formulate a questionnaire focused on the behaviors reported. The mean findings (as reported by the caregivers) are shown in Figure 4. Regarding benefit from hearing aid use in general, improvement was noted for all areas (e.g., a mean rating of 3.0 or better). Interestingly, for two areas, awareness and alertness, the ratings were significantly higher (p<.05) when TeleCare was used. This certainly could be partially related to the remote programming of the hearing aids when the need was present. It’s also possible that a contributing factor was the increased communication regarding the hearing aids via TeleCare, which might have simply made the caregiver more aware of the benefits of amplification for the participant.

Figure 4. Displayed are the mean ratings (completed by the caregiver) for the five different general areas of behavior potentially related to hearing aid use. Mean values for TeleCare use versus when TeleCare was not used are shown. Ratings conducted using a 5-point scale, 1=Worse to 5=Much Better. Significant differences (p<.05) between the TeleCare condition are denoted by an asterisk (Adapted fromJorgensen, Van Gerpen, Powers, & Apel, 2019).

Caregiver Burden

The caregiver completed an 11-question burden scale following each 3-week segment. We need to point out that most burden scales are designed for caregivers who are dealing with issues much more severe than someone using hearing aids for the first time. Caring for a bed-ridden significant other is much more burdensome than helping someone change the battery of their hearing aid. Additionally, the participants in our study only had mild cognitive decline, which again reduced the burden. For these reasons, the mean ratings for nearly all items on the 1 to 5 burden scale (5=Extreme Burden) were below 2.0, with many near 1.0 (no burden). There was one exception, however, which was for the item: “How much stress do you feel between taking care of the care receiver and trying to meet other responsibilities of work and family?” This item had a mean 3.0 rating when TeleCare was not used, but importantly, it was lowered to 2.1 during the period of TeleCare use, a significant difference (p<.05).

TeleCare Acceptability

The acceptance of TeleCare by the caregiver was rated on a 7-point scale (1=Significantly Disagree, 4=Neutral, 7-Significantly Agree). Positive findings were obtained for all three of the questions asked. TeleCare helped with concerns and needs related to the hearing aids: Mean=4.7. Was easy to use: Mean=5.9. Reduced stress: Mean=5.4. For all three of these questions, only 15% of the responses fell in the “Neutral” category, and no responses were below Neutral. As we discuss later in this paper, these ratings were significantly impacted by whether the participant was in Phase 1 (TeleCare first three weeks) or Phase 2 (TeleCare second three weeks), with higher ratings for Phase 1. Given that in clinical practice, TeleCare usually is implemented in the first three weeks, the average values stated above probably under-estimate the true acceptability.

MMSE and COSI Score

The mini-mental state examination (MMSE) is a widely used test of cognitive function among the elderly; it includes tests of orientation, attention, memory, and language. The maximum score is 30 points. As previously stated, we used the education-corrected scores, and included individuals who fell below a score of 28. An analysis was conducted to determine if there was a relationship between the COSI benefit, the use of TeleCare and the participant’s MMSE score. No significant findings were found. The correlation between the MMSE and COSI “with Telecare” rating was R=0.11 (p>.05), and “without TeleCare” R=0.13 (p>.05). The correlation between the MMSE and the COSI rating difference (with vs. without) also was not significant (R=0.08; p>.05). The TeleCare benefit, therefore, did not appear to be related to the participant’s MMSE score, although the range of scores was relatively small, with none falling below 23 points.

Phase 1 vs Phase 2 TeleCare Use

Recall that this was a cross-over research design, with ½ of the participants using TeleCare the first three weeks, and the other ½ using TeleCare the second three weeks. We questioned if the ordering of the use of TeleCare influenced the outcomes with TeleCare; we examined both the burden scale and the ratings for TeleCare use in general.

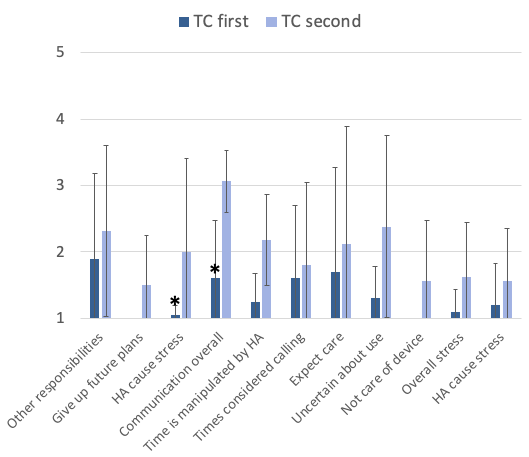

Shown in Figure 5 are the burden ratings for those who had TeleCare the first three weeks versus the second. Observe that there is general trend for all 11 questions for the burden scale to be lower (less burden) when TeleCare was used during the first three weeks (see Figure 5). Two of the items were statistically significant (p<.05):

“In the past three weeks, regarding hearing-aid related care, how much extra stress or burden has that caused?”

“In your opinion, over the past three weeks, during a typical listening day, how much difficulty does the care-receiver have with his or her hearing and communication?”

Figure 5. Shown are the mean findings of the Burden Scale for those participants who used TeleCare during Phase 1 of the study, vs. those who used TeleCare during Phase 2. There were 11 questions related to burden, and they were rated on a 1 (little or no burden) to 5 (significant burden) scale. Significance (p<.05) is indicated by an asterisk. (Note: Where bars are not visible for the Phase 1 group, mean values were 1.0).

Observe that when TeleCare was implemented during the first three weeks of hearing aid use, no item on the Burden Scale reached a mean rating of 2.0 (some burden), whereas when it was implemented in the second phase of the study, 6 of the 11 items met or exceeded this burden rating level. From a clinical standpoint, TeleCare usually is implemented immediately after the fitting, so these findings support this approach. These data of course are only based on two groups of 10 participants, and it is possible that those who used TeleCare the second ½ were more impaired, although there was no significant difference in the mean MMSEs.

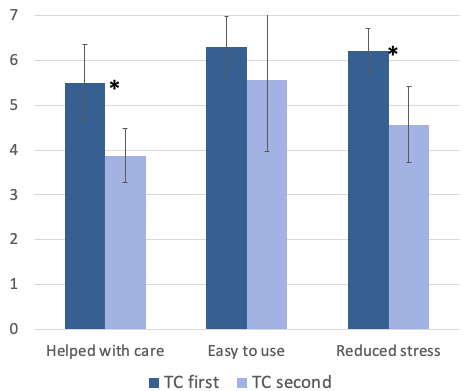

A second area where the order-effect was examined related to the caregiver’s ratings for the acceptability of TeleCare. The mean findings comparing the Phase 1 vs. Phase 2 ordering of TeleCare are shown in Figure 6. As with the burden scale, there were higher (better) ratings when TeleCare was used during the first three weeks. These findings were significant for “helped with care,” and “reduced stress.” It’s possible that these results reflect that many post-fitting problems occur during the first three weeks, and some had been resolved without TeleCare for the Phase 2 group. But again, this supports why TeleCare should be implemented at the time of the fitting. Also, given that TeleCare nearly always is implemented in the first three weeks, the mean findings of acceptance shown here (Figure 6), should be considered more representative of “average” than what we presented earlier, which included those on both Phase 1 and Phase 2 of the study. For example, when Phase 1 and Phase 2 are combined, the mean for “Reduced Stress” was 5.4, whereas when we only look at the Phase 1 group, this rating was 6.2.

Figure 6. Shown are the mean findings of the TeleCare Acceptance Scale (as reported by caregivers) for those participants who used TeleCare during Phase 1 of the study vs. those who used TeleCare during Phase 2. Each item was rated on a 7-point scale (1=Significantly Disagree, 4=Neutral, 7=Significantly Agree). Significance (p<.05) is indicated by an asterisk.

Summary and Conclusions

Changes in communication functioning due to cognitive decline, together with behavioral changes, can have a significant impact on day-to-day interactions and can result in considerable frustration. Family members and those who care for individuals with MCI and dementia are faced with challenges that can affect their own health and well-being. One of these challenges occurs when the patient with MCI or dementia is fitted with hearing aids. Working with caregivers to use effective strategies that enhance communication and maximize the benefits offered by hearing aid use, may help them engage in conversation more successfully, and improve quality of life for the individual with cognitive concerns.

Our findings show that at least through the eyes of the caregiver, using TeleCare significantly enhances specific listing goals for the patient with cognitive decline. Not only are communication goals improved, but awareness and alertness also are significantly impacted. Moreover, the caregiver reports less stress when TeleCare is used. These improvements are observed more in the first three weeks than after—important in that this is the most critical time frame related to hearing aid adoption. These results also suggest that the majority of the post-fitting problems can be solved via TeleCare in the first three weeks with minimal need after those three weeks.

Clearly, involving caregivers in the fitting process, facilitated through TeleCare, will help maximize hearing aid benefit and satisfaction for the patient with cognitive decline.

References

Alzheimer’s Association. (2012). 2012 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures.

Anderson Gosselin, P., Gagne, J.P. (2011). Older adults expend more listening effort than young adults recognizing speech in noise. Journal of Speech, Language & Hearing Research, 54, 944–958.

Blieszner, R., & Roberto, K.A. (2009). Care partner responses to the onset of mild cognitive impairment. The Gerontologist, 50, 11-22.

Cherko, M., Hickson, L., & Bhutta, M. (2016). Auditory deprivation and health in the elderly. Maturitas. 88: 52-57.

Dawes P, Cruickshanks K, Fischer M, Klein B, Klein R & Nondahl D. (2015)

Hearing-aid use and long-term health outcomes: Hearing handicap, mental health, social engagement, cognitive function, physical health, and mortality. International Journal Audiology. 54 (11): 838-844.

Dillon H, James A, Ginis J. (1997) Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and Its Relationship to Several Other Measures of Benefit and Satisfaction Provided by Hearing Aids. J Am Acad Audiol 1997. 8: 27-43

Froehlich, M., Branda, E., Apel, D. (2018). Signia TeleCare facilitates improvements in hearing aid fitting outcomes. AudiologyOnline, Article 24096. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

Hall, D., Wilkerson, J., Lovato, J., Sink, K., Chamberlain, D., Alli, R., . . . Shaw, E.G. (2014). Variable associated with high caregiver stress in patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications for providers in co-located memory assessment clinic. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36, 145-159.

Jorgensen L, Van Gerpen T, Powers TA, Apel D. (2019) Benefit of using telecare for dementia patients with hearing loss and their caregivers. Hearing Review. 26(6):22-25.

Lin, F.R., Yaffe, K., Xia, J., Xue, Q.-L., Harris, T.B., Purchase-Helzner, E. (2013) Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173, 293–299.

Lynch, S.H., & Lobo, M.L. (2012). Compassion fatigue in family caregivers: A Wilsonian concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68, 2125-2134.

Palmer, C., Adams, S., Durrant, J., Bourgeois, M., & Rossi, M. (1998). Managing hearing loss in a patient with Alzheimer Disease. Journal of American Academy of Audiology, 9, 275-284.

Paradise, M., McCade, D., Hickie, I.B., Diamond, K., Lewis, S., & Naismith, S.L. (2015). Caregiver burden in mild cognitive impairment. Aging and Mental Health, 19, 72-28.

Petersen, R.C., Smith, G.E., Waring, S.C., Ivnik, R.J., Tangalos, E.G., & Kokmen, E. (1999). Mild cognitive impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Archives of Neurology, 56, 303-308.

Sebastian, S., Varghese, A. & Gowri, M. (2015). The impact of hearing loss in the life of adults: A comparison between congenital versus late onset hearing loss. Indian Journal of Otology, 21, 29-32.

Weinstein, B. (2017). Preventative care for dementia and hearing loss. The Hearing Journal, 18-20.

Citation

Jorgensen, L., Van Gerpen, T., Powers, T. & Richter , L. (2019). Implementation of telecare for new hearing aid users with mild dementia. AudiologyOnline, Article 25795. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com