Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live webinar. Download supplemental course materials.

Background

Today's course is a continuation of a series of courses and papers I have done, some of which are courses here at AudiologyOnline. One was called The Creative Destruction of Audiology and another was related to strategy, The Five Key Drivers of Customer Intimacy in Hearing Care. Those courses talked about an economic term called creative destruction, which ties into our topic today. A good example of creative destruction within a profession is that of a cooper, or barrel maker. In the year 1900, this was the third or fourth most popular profession in the United States, and by about 1930, because of technology, electricity, refrigeration, and automated processes, the profession of coopering went almost out of existence.

I like to draw the parallel to audiology, because some of those same forces that changed coopering are potentially at work with audiology. Figure 1 is a picture of a student at the University of North Texas who has essentially turned her smart phone into an amplifier or a body aid. That is an example of available technology that could change the focus in the value proposition that audiologists bring to the marketplace. That is what we are talking about today: changes due to technology.

Figure 1. Student using smart phone as a personal amplifier.

The person that coined the term creative destruction in relation to business was an economist, Joseph Schumpeter. He died in 1950 and had spent the last 20 years of his career at Harvard University. One of my favorite quotes from him is, “All established businesses are standing on ground that is crumbling beneath their feet,” which essentially is a nice way of saying that technology changes what customers might value, and it is up to all of us to stay ahead of that curve and find new ways to be relevant in the marketplace.

Another concept that was talked about in previous courses leading up to today was something called the discipline of market leaders. This gets at strategy. The name of the book is also titled The Discipline of Market Leaders (Treacy & Wiersema,1997). Their work helps us better understand how leading companies find one area within the marketplace around which to build a dynamic business. They are leaders at operational excellence, which means having a very efficient operation. They may lead on innovation or on being the best at customer intimacy, which is delivering a highly individualized, customizable experience to individuals that are coming in.

I like to argue that if you are in a smaller independent practice, the only choice you have as far as trying to lead your market would be customer intimacy. Big-box retail hearing aid chains are leaders on operational excellence because of their economies of scale. In our industry, I think it is very difficult to try to lead or differentiate based on innovation, because we all have good, comparable products. Therefore, if you are in an independent practice, I think the only dimension on which you can focus would be customer intimacy.

What I have talked about so far is a summary of some of these concepts that we are going to continue with today. If you want to learn more, you can go back to the links I provided.

There are three questions that I want to cover today. The first one is, “How has audiology in the marketplace for our services evolved over the past 40 years?” The second one is, “How does audiology fit into the evolving healthcare system in the United States?” Finally, the most important and practical question is, “What do audiologists need to do as we move into the future to create value for our patients and revenue for ourselves?” After all, we do have to earn a living if you want to stay in business during all this time of change.

The Evolution of Audiology over 40 Years

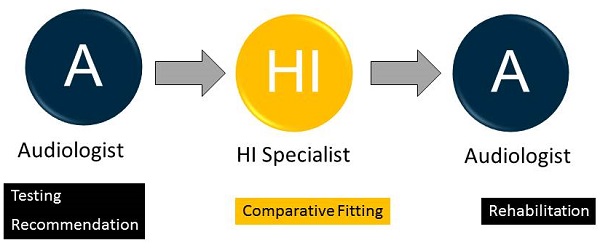

How has audiology and the marketplace for our services evolved over the past 40 years? I think it is important to step back and remember that until the late 1990s or even the early 2000’s, we lived in a very analog world, considering we still made use of tape players and record players. When was the last time you saw a rotary phone, for example? When we talk about an analog world as it relates to hearing technology, we think about limited product options, limited features, and limited adjustments. There were not that many choices through the 1990s, but things have changed quite a bit. That is the industry as a whole, but I will focus more carefully on the profession of audiology. If we go back to 1974, the profession looked something like the schematic in Figure 2

Figure 2. The professional model of audiology, circa 1974.

There was the audiologist, who passed their patients over to the hearing instrument specialist, who then, very often, passed the patient back to the audiologist. First, the audiologist did the testing and recommended the product. Then the hearing instrument specialist did some type of a comparative evaluation to determine which product would be best for the patient. Then finally, the audiologist provided any counseling, follow-up, auditory training, or rehabilitation. When you hear professors or read articles about to the roots of audiology, oftentimes they are talking about the function of providing rehabilitative services, which was only done after the hearing instrument specialist provided the hearing aid fitting.

What has happened in the last 10 years, in particular, is this digital revolution where we have products that are upgradable, wireless, incrementally improving, and becoming faster and smarter. You might even argue that they are becoming cheaper to manufacture. That leads to what I call the tyranny of the digital unit. The trouble that we have gotten ourselves into, in my opinion, is that the product has become the focal point, and the product, for various reasons in the digital era, has become commoditized. Therefore, the profession in a few ways is becoming commoditized, and that means that there are a lot of reasonable substitutes available.

What do I mean by reasonable substitutes? There is a blurring of these different professions. Both the audiologist and the hearing instrument specialist do the testing and recommendations. They do the manufacturer-driven prescriptive fitting, and they do the tweaking of the device. My point here is that everything essentially revolves around the digital device, and more than one profession is able to do these things. I would even argue that modern technology with remote fittings, smart algorithms, and self-guided apps is replacing the professional, and that is particularly dangerous when what people might value from our profession revolves around a commoditized product.

Back to our first question, which sets the stage for some of the meatier things: “How has audiology and the marketplace for services evolved?” I would argue that audiology has become synonymous with dispensing a device; everything revolves around that. The value of audiologists has been substituted by other professions, as well as by technology. In the era in which we live, consumers have access to a tremendous amount of information, including information that comes directly from manufacturers. Every manufacturer that I know has a consumer-oriented website, where people can do as much comparison shopping as they want. In this world where there is an abundance of information and a reasonable substitute for the services that audiology has performed over the last of many generations, it means that the profession is at a turning point.

The second thing I want to talk about that is changing as we speak is related to how audiology fits into the evolving healthcare system in the United States. As you may know, there is a tremendous amount of buzz in healthcare centered around cost, access, and value. How does audiology fit into some of those changes? Healthcare, in very general terms was very provider-centric and procedure-based under the old model (Topol, 2012). Most medical professions are reimbursed based on the procedures that they perform. Healthcare historically has been a very paternalistic, top-down system, where the physician or medical profession is known as the all-knowing expert, and the patient does not have access to much information and relies on the expert to tell them what to do.

Modern Healthcare

That old system has very rapidly evolved over the last few years. In the new healthcare model, you have the super convergence of an abundance of technology, such as the Internet, social networking, wireless sensors, imaging, genetic mapping at a relatively low cost, mobile connectivity and bandwidth. You have this technology that allows the consumer to now actively participate in the delivery of healthcare. Consumers are much more knowledgeable. They go to websites to sometimes self-diagnose themselves. They have apps that help them measure bodily functions and fitness. All of these things are changing, or creatively destroying, the way healthcare is delivered.

If there is one term that I think summarizes this movement, it is called the quantifiable self, which is our ability through the use of technology, namely smart phone apps and other kinds of body sensors that are produced inexpensively, to measure and learn a lot about how our body works without having to visit the physician. There is no shortage of these apps. Maybe one of the side questions might be, “How does audiology fit into this quantifiable self-movement?”

There are many exciting and interesting things currently happening in the medical literature. If you read the British Journal of Medicine, the New England Journal of Medicine or the Journal of the American Medical Association, you will realize that the modern system is evolving very rapidly. If there was an easy way to summarize what that evolution looks like, it would be the four P's of modern healthcare. Mainly due to modern technology and our ability to measure, the treatment and the diagnosis can be personalized on an individual basis. It is preventive, which means there are all kinds of opportunities to engage patients in the identification of a mild condition earlier rather than when the condition gets more serious. It is preemptive or interventional again. It is much more participatory. It is much easier for people to interact with their healthcare worker with modern technology.

The bigger question though for us would be “How do we fit into the system?” One way to look at this is that physicians are being trained differently and are approaching the marketplace differently because of those four P's. Physicians now are being taught and are embracing the concept that they are more or less the leader of a pit crew rather than a cowboy, who is intending to be the all-knowing expert (Gawande, 2013). When physicians view themselves more as leaders of the pit crew, I think there is an abundance of opportunities for us to get involved in working with their patients at a younger age when hearing loss might be milder. This pit crew mentality, especially amongst younger physicians, is something that we can leverage in our practices.

The National Institutes of Health looked at when males and females first notice that they have a mild hearing loss. About a third of males between the ages of 20 and 39 and another third between the ages of 40 and 59 are first noticing a hearing loss at a much younger age than when they first see us in our clinic (from Bouton, 2014). This data tells me that there is an opportunity to engage these people that are between the ages of 20 and 60 who are in the process of having their hearing monitored to make sure that they are not mishearing important parts of life.

If you dig deeper, there is more than enough opportunity around this concept of engaging people at a younger age when the loss might be less severe. You can look no further than the work of Frank Lin (2014) at John Hopkins. He is showing that age-related hearing loss is a public health concern. There is a rise of accountable care organizations, which tells you that physicians are being incentivized to practice preventive medicine; there is a role for audiology there.

There is also a rise of what we call population-based medicine. I already talked about quantifiable self-movement. We know that for every one audiologist or hearing instrument specialist, there are 12 primary care physicians. That tells you that there are more than enough physicians that need to hear about age-related hearing loss as a public health concern.

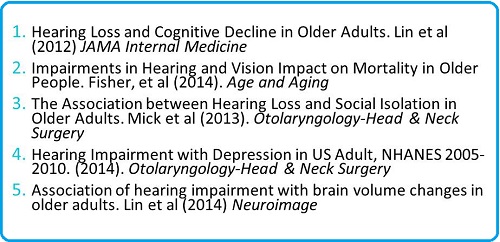

An important part of raising awareness within your community around this concept of the discipline of customer intimacy would be what I call pillars of community marketing. This is where you try to form deep long-lasting relationships with three primary areas of your community: patients, primary care physicians, and the community in general. When you are dealing with primary care physicians, your conversation needs to revolve around what I call the common soil argument, which is summarized by Dr. Lin (2014). This model maintains that hearing loss, some of the issues related to the changes in cognition, along with aging and microvascular diseases, like diabetes and cardiovascular disease, all share a common etiology that results in poor physical functioning and poor overall quality of life. If you want to learn more about this, I would point you to the five articles listed in Figure 3. All have been published in the last few years and delve into the relationship between various etiologies and their impact on age-related hearing loss.

Figure 3. Articles address hearing loss and its effects on cognition and mental functioning.

Some considerations for audiologists who are part of an evolving healthcare system are:

- Educating physicians on the consequences of untreated hearing loss;

- Engaging patients earlier in the process by using self-guiding assessment apps that help people screen their hearing;

- Thinking about hearing loss as part of a bigger picture, including quality of life;

- Using advertising that triggers positive engagement with individuals towards hearing care professionals

There is a good article from Curtis Alcock in the UK called Trigger Happy Hearing (Alcock, 2014) that talks about advertising and public awareness campaigns intended to trigger positive engagement with our profession.

Creating Value

Given this constellation of circumstances, how can audiologists continue to create value for patients and revenue for themselves in this time of change? A corollary to this question is, “What can we unbundle from the device?” That question, I hope, will make a little more sense as we move through the second half of today's material.

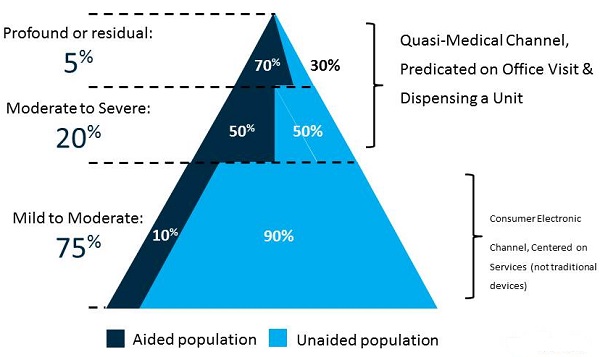

Let’s look at the market based on degree of hearing loss (Figure 4). I like to call this the great unmet need. This pyramid shows that 5% of those with a hearing impairment have a profound loss, and 70% of them are using a hearing aid or cochlear implant, which is not too surprising. If you move down to the middle of the pyramid, you see all of the individuals that have a moderate to severe loss, which comprises about 20% of the total hearing-impaired population. Roughly half of those people wear hearing aids, and the other half do not. Market penetration for the middle of the pyramid is 50%. Then, there is the “great unmet need,” which is 75% of the total hearing-impaired population with mild to moderate hearing loss. Only 10% are using hearing aids, and the other 90% are not. For obvious reasons, some of them are not using amplification because their loss does not warrant it yet. This is where there are some opportunities for us to create value.

Figure 4. Market segment based on degree of hearing loss. The unmet need lies in the greatest proportion of the pyramid, mild to moderate hearing loss, where only 10% of those hearing-impaired people are using amplification.

Another way to look at this is by of the items on the right side of the pyramid (Figure 4). I would argue that the middle and top of the pyramid is the medical channel. These are the people that do well under the existing practice model, where someone comes in for an office visit and hearing test, comes back for the fitting and then a series of follow-ups. It all revolves around the office visit and our ability to dispense and fine-tune hearing aids. However, for the bottom 75% of the pyramid, I would say that that model is not very effective. Those are people who are much more amenable to some type of an over-the-counter device or a service that may not even involve a hearing aid or any kind of an amplification device, or to working with a hearing professional remotely. For these milder losses, maybe there is a way to create value that is not predicated on making multiple office visits. Those are some things to think about when we talk about the great unmet need of the 75%. Remember that 90% of that group do not use or do not want or need hearing aids.

I want to focus on some things we can do in our clinic to create value for the 75% of the population with hearing loss that does not come in to see us. The first goal is to attract younger patients. How can we attract patients with milder hearing loss at a younger age? How can we provide a service model that is less dependent on dispensing traditional devices? Can we find a unique value proposition that is not easily duplicated by other professions? These are very important questions, because if other professions can offer the same level of service (e.g., a reasonable substitute is available), that does not bode very well for the profession of audiology. We are looking for a way to add value and by offering a service that other professions cannot easily duplicate. I think the way to go about this is by decoupling services from the device. But how do we engage them early? How do we complete a functional assessment?

Individualizing Care

We will discuss a process for dealing with patients who are candidates for devices but still might value a service. Before I do that, however, I want to talk about an interesting model about individualized care that comes from Australia. This was published in February 2014 in the International Journal of Audiology by Grenness and colleagues. They conducted an analysis of a large group of very satisfied patients, and they found that the most important dimension that led to satisfaction was the ability of the clinician to offer individualized care. For most of us, that seems pretty obvious. They found that the two clinical processes that drove a patient's to feel that they were receiving impeccable individualized care was the audiologist’s ability to be effective at exchanging information as well as being effective at helping patients make decisions and solve problems. In this model, the researchers call it a therapeutic relationship. The main drivers of that therapeutic relationship were the audiologist’s ability to inform the patient in a meaningful way and get them more involved and participating in the interaction. If you can do those two things, it is much more likely to lead to the perception that care is individualized. This gives us valuable information about the patient’s perspective.

Based on that model, I have come up with five things that we can do to individualize care for those patients that do not ordinarily see us because their loss is too minimal, they are too young, or they do not think they have a problem. What are some things that we can do to attract those patients and offer them something of value for which they might be willing to pay? I came up with these five steps to individualizing care for mild to minimal hearing loss.

Engage People Early

The first one is to engage people at an earlier age in the process of hearing screening. To give you an example, Figure 5 shows a prototype of a public awareness announcements that we have come up with as part of an ADA task force. It shows someone at a very young age, and the verbiage uses the term mishear, not hearing loss. It talks about how you can take charge of your hearing. We think that this kind of proactive campaign is a way to engage people at a much earlier age in the process of understanding mishearing. Then they will come in to see you for a hearing screen. I think that is pretty well stated in the ad.

Figure 5. Public awareness announcement for hearing awareness.

Some other ways to do that would be to get patients involved in using an app to screen their hearing. There are kiosks available that now allow people to screen their hearing while they are waiting to get their medication at the pharmacy. Any kind of technology that gets patients engaged in the process, hopefully at a younger age, is very useful for our profession.

Consumers are searching for a provider. They are looking at technology and reading reviews about devices. We want to make sure that we are involved and have a presence in this technology. Abram Bailey is an audiologist and president of a company called Hearing Tracker. This tool allows professionals to have a presence on the web and in social media when people are searching for a provider or looking at hearing devices.

Address Real-life Communication Difficulties

The second step is to address the individual’s real-life communication difficulties. I want to talk about a functional communication assessment. It really has nothing to do with the audiogram. Rather than be guided by the results of the traditional audiogram with air, bone and speech, we can be guided by other functional communication assessment tools that will help us make decisions and guide the process, especially for those with minimal or mild hearing loss. We will review motivational interviewing, or scaling questions, which is a subsection of motivational interviewing, and then goal planning and assessment.

Motivational interviewing. The idea here with these milder losses is to get them more involved in the process. We need to connect the behavior change with the patient's values and what they care about and honor the patient's autonomy. These principles work with all of our patients, but based on what I have seen, done, and read, I think these principles of motivational interviewing are especially powerful with younger patients who have milder hearing loss. If you delve into the concept of motivational interviewing, there are probably two questions that warrant more consideration. That is the patient’s self-perception of the hearing handicap. How bad is it? The second concept is their willingness to receive help. Those are two completely separate concepts that warrant our attention in the motivational interviewing process.

The first question centered around the perception of handicap can be answered by asking this scaling question to the patient: On a scale of 1 to 10, 1 being the worst and 10 being the best, how would you rate your overall ability (Palmer, Solodar, Hurley, Byrne, & Williams, 2009)? You will notice that this has nothing to do with the audiogram. There is no relationship between the scores on the audiogram and the patient’s self-perception of their possible handicapping condition. Patients who answer somewhere between an 8 and a 10 are probably not noticing much of a problem, or they are in denial. These are patients that probably would benefit from further education. Perhaps they would not benefit from a trial with some type of over-the-counter device or smartphone app for highly situational use. The bottom line with this group is to provide them with more educational information, and make sure you get them involved in the process of having their hearing screened on a routine basis.

Next, you have the people that answer 1 through 5. These are probably the people that fall in the middle to upper part of the pyramid (Figure 4). These are patients that are very amenable to the traditional hearing aid selection and fitting approach.

Finally, we have the people in the middle that answer between 6 and 7. These people account for about a third of the patient population we see. These are patients that are very amenable to some type of an at-home demonstration. Essentially, they need more information prior to making a decision. My point here is that we can use that scaling question to get a better feel for the patient's perception of a handicapping condition. However, just because someone is noticing a handicapping condition, it does not mean that they are willing, able, and ready to receive help. That is where this model of health behavior change comes in handy.

Health behavior change. Laplante-Lévesque, et al. (2012) have done a lot of work around the concept of readiness to receive help. There are four stages from when patients first notice a problem to when they take action. Those are pre-contemplation, contemplation, action, and maintenance. There are a certain set of behaviors associated with all four of these stages. You can use the following scaling question to cut right to the chase: On a scale of 1 to 10, 1 being not ready at all and 10 being ready today, how ready are you to move ahead with an agreeable treatment option? That is a question from the patient's point of view that helps you assess their readiness to move ahead with a particular recommendation.

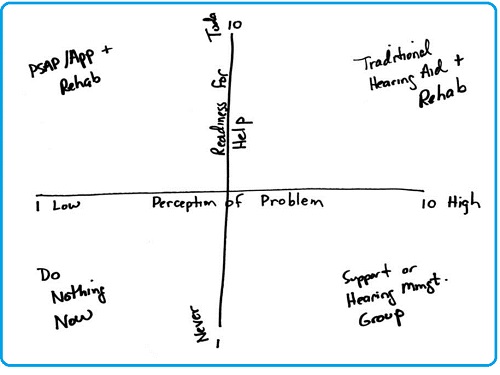

I am a big fan of the four-quadrant matrix as a decision-making tool. Figure 6 is a very crude diagram of how you can use those two scaling questions to come to a decision in a collaborative way with the patient. For the first four-quadrant matrix, on the horizontal axis, you have the 1 to 10 scaling question for the perception of the problem. Then on the vertical axis, you have the second question regarding their readiness to move ahead with the recommendation. When you cross the lines, you get four distinct quadrants. You move from low to high when you go from left to right, and you go from not ready to totally ready from bottom to top of the vertical line. This is what it looks like when you start thinking about the patient's perception of the problem and the readiness to receive help.

Figure 6. Decision-making matrix as a function of perception of problem (x-axis) and readiness for help (y-axis).

In the top left quadrant (Figure 6) where there is a low perception of the problem and a high readiness to do something about it, these patients might be willing to try some type of over-the-counter device, app, or perhaps come in for a hearing management workshop or group therapy session where they are learning to overcome some of the handicapping conditions related to hearing loss.

If the patients fall into the bottom left quadrant where they have a low perception of the handicapping condition and they are not ready for help at all, likely no amount of talking, persuading or cajoling is going to be effective. The best thing to do is to show them how to use a self-guided app, get them engaged in the process of screening their hearing on a routine basis, and raise their awareness about hearing loss and its effect on day-to-day functioning.

If they fall into the top right quadrant with a high perception of the problem/high readiness for help, then they are probably amenable to traditional solutions like hearing aids and our ability to conduct aural rehabilitation.

Then, we have the bottom right quadrant where the patient might have a high perception of the problem but is not ready to do anything about it yet. They do not want to make the investment, money or time, of getting used to hearing aids. Those patients may be more amenable to a softer kind of approach which revolves around a support group or a hearing management group.

My main point of showing this is to help you understand that there are several different possibilities of delivering services outside that of dispensing a traditional device. Assuming that you can get more patients in your door with a milder hearing loss, there other possible solutions here that have nothing to do with traditional amplification.

Provide an assortment of treatment options. That brings us to the third of my five steps, and that is to provide a full assortment of treatment options. I think you have a good feel for that in the matrix, but I wanted to discuss some research from Robin Cox (2014) that appeared recently for 20Q on AudiologyOnline. When you have the ability to expand some of your treatment options, you can help many more patients, particularly those with milder hearing loss. We have traditional hearing aids. We have hearing management groups, hearing skills training, an assistive listening device, cochlear implants, or nothing.

I want to share with you one example which comes from Louise Hickson out of Australia. She is a prolific researcher. She devised something called the Active Communication Education, or ACE program. This is a support group comprised of a relatively small number of people for a few hours a week over five weeks. This is very interactive with programmed instructions. It focuses on behavioral and attitude change. Hickson and colleagues (2007) published a randomized control study demonstrating that ACE is a very useful alternative to traditional hearing aid use. If you are looking for ways to expand your scope of practice and create value for an unmet segment of the population, I think offering services like this is highly beneficial.

Facilitate decision-making process and a plan. That brings me to step number four, which is to facilitate the decision-making process and a management plan. Rather than focusing on dispensing a device, I want you to re-think how we can offer services that do not center on the device. One way to do that is to use what is called a goal planning sheet. This work that comes from the 1980s (McKenna, 1987). As a side note, through 1999, there was a period of about 20 years where there was a tremendous amount of good research that came mainly from Europe and Australia about auditory training, hearing rehabilitation, goal planning, and motivational interviewing. When digital technology came out, many of us put all of our eggs in the technology basket, thinking the sophisticated digital product would overcome some of the long-term barriers associated with hearing loss. Having lived in the digital world for 20 years, we realize that in most cases, hearing aids still have some serious limitations. My challenge to you is to go back and revisit some of this research from the ‘80s and early ‘90s around hearing rehabilitation, goal planning, and behavior change.

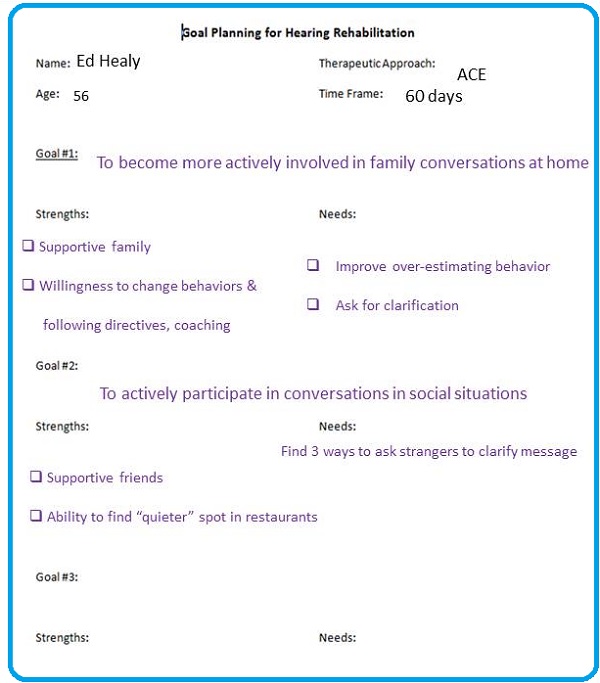

The result is rather than focusing on the device, you can now focus on the goals or behavior changes on which the patient needs to focus. Figure 7 is a Goal Planning for Hearing Rehabilitation form. It has the patient's name and age. It includes the therapeutic approach, and that could be hearing aids. It could be a hearing management group. In this case, it is the ACE program that I mentioned. It has the timeframe. I am going to work with this patient closely for the next 60 days. It has room for three goals; I only have two listed there.

Figure 7. Goal Planning for Hearing Rehabilitation form.

The first goal is to become more actively involved in family conversations at home. The second goal is to actively participate in social conversations. You will notice under each goal that strengths are listed. What is the patient doing well? To what do they have access that is going to help them achieve the goal? What are some things that they might need or perhaps have to address in order to achieve the goal?

Under goals (Figure 7), the strengths are the things the patient has to their advantage. In this example, strengths are a supportive family and a willingness to change behaviors and follow directives and being open to coaching. Strengths were identified during the initial interview process. We want to make sure we keep those in mind and leverage those things as we work with the patient. As far as needs are concerned, we found that this patient was overestimating their behavior to communicate in noise. We honed in on the fact that they need to ask for clarification. The point here is that you are focusing on changes in behavior and not on tweaking a device. I would say that this type of a tool is a highly effective way to engage with patients, no matter the amount of hearing loss or what their outlook is towards amplification or help.

A big part of this is getting the patient to commit to the recommendation. I would add that our industry could use more research on the use of what are called commitment devices. The idea here is the patient has to do something. They have to have a strategy in place that is going to help them achieve the goal. A recent article from the Journal of the American Medical Association (Rogers, Milkman, & Volpp, 2014) shows a number of different commitment devices, the description, and then the goal that might be involved. A good example of a universal commitment device would be if patient has to put money in a deposit contract and otherwise forfeit the money if they fail to achieve the goal. I am not saying that you literally take money from the patient and they do not get it back, but this is something that maybe they do at home with their spouse. The main idea here is that commitment devices are highly effective when you are focusing on trying to change patients’ outlook and behavior.

Follow-up, document and advocate. That brings me to the last step which is follow-up, document and advocate. Again, the overarching idea here is that you want to be more collaborative with the patient, and there are some tools that are highly effective at doing that. One would be a patient journal, to get the patient involved in writing down a few notes on how things are working with respect to the treatment recommendation on a daily basis. In this case, we are talking about hearing aids, but it certainly does not have to be confined to that. I am involved in one study that has not yet been published that shows that patients who are involved in the journaling process report a higher level of interaction and engagement with the professional when they are allowed to journal. A journal is also nice way to tease out some of the more subtle benefits of hearing aid use if that happens to be the treatment option.

Another tool that you can use to measure improvement, regardless of the treatment strategy, is the SSQ12 (Noble, Jensen, Naylor, Bhullar, & Akeroyd, 2013). This is a short version of the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing (SSQ) questionnaire. This can be used for patients who are working on behavioral changes, even those that do not wear hearing aids, in order to gauge the effectiveness of whatever treatment option you are giving. If you are interested in the SSQ as a way to measure the effectiveness of your treatment recommendation, you can go to the website, https://www.ihr.mrc.ac.uk/products/display/ssq, and download a copy of the SSQ, along with the normative data.

Conclusions

Here are some final thoughts with respect of our topic, The Reconstruction of Audiology. The first one is to think about how you can offer different service packages for different segments of the market. I have talked about how we need to tap into the market with minimal and mild hearing loss. The traditional solutions revolving around the devices have shown, over time, to be highly ineffective at engaging that segment of the market.

Number two, we need to find approaches for managing hearing the health of younger individuals with mild hearing loss. This has to do with how we trigger positive interaction, and I would again encourage you to read Trigger-Happy Hearing, which has to do with the way that we market and advertise our services.

Number three, strive to become a pillar of community, which means within your town or your area. Make sure that you have branded yourself as the expert around all matters related to hearing and better communication. Hearing aids are only one small part of that.

Number four, look at ways to unbundle specific services and broaden the scope of your practice. I will show you an example of what I mean by that in a minute. It summarizes what we talked about.

Number six is to remember that hearing aids are a means to an end. The desired end result is a positive behavior change in our patient and the formation of a more favorable outlook on life or their ability to become more actively involved in life; a hearing aid is not always part of that equation. One of the biggest mistakes we made in our profession years ago, in my opinion, was focusing too much on digital technology. By doing so, we missed out on some other golden opportunities.

I would like to give you a feel for some of the exciting things that are happening. Some of you might know Ian Windmill from the University of Mississippi Medical Center. He has come up with an interesting way to look at unbundling for straightforward versus complex cases in three different interactions (Windmill, 2014). One is the assessment of hearing status and hearing handicap. The second is audiological decision-making, and the third is treatment and counseling. If you are looking for ways to unbundle services, consider reading this article. Admittedly, we have a lot of work to do as a profession when it comes to unbundling our services. I am presenting this as food for thought.

Preminger and Laplante-Lévesque (2104) created a nice diagram to address our unique value proposition and how we can broaden our scope of practice. It shows how the rehabilitation part of what we do intermingles and cuts across the healthy aging process and cognitive changes to the brain. If there is any way that we can operationalize services around helping people cope with the aging process and perhaps identify ways to retrain the brain and become better communicators, we might be able to offer those services that are not duplicated by other professions. Admittedly, we have a lot of work to do in these areas, but I am presenting this as something to think about as we move into the future.

I will leave you with a quote from Steve Jobs, “The people who think they are crazy enough to change the world are the ones who do so.” I would strongly encourage you to look for ways in your practice to attract these younger patients with mild hearing loss. Think about ways to deliver services that do not revolve around the dispensing of a device. We already do a good job in that area, but it is not something that the majority of the market values. It is up to us to create some new value propositions.

References

Alock, C. (2014, June). Trigger happy hearing. Audiology Practices, 6(2), 8-16.

Bouton, K. (2014, January). Consumer perspective on the impact of hearing loss. Presentation at Hearing loss and healthy aging: An Institue of Medicine/National Research Council (IOM/NRC) workshop. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from www.iom.edu

Cox, R. (April, 2014). 20Q: Hearing aid provision and the challenge of change. AudiologyOnline, Article 12596. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

Gawande, A. (2011, May 26). Cowboys and pit crews. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com

Grenness, C., Hickson, L., Laplante-Lévesque, A., & Davidson, B. (2014). Patient-centered audiological rehabilitation: perspectives of older adults who own hearing aids. International Journal of Audiology, 53(Suppl 1), S68-S75. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.866280.

Hickson, L., Worrall, L., & Scarinci, N. (2007). A randomized controlled trial evaluating the active communication education program for older people with hearing impairment. Ear and Hearing, 28(2), 212-230.

Laplante-Lévesque, A., Knudsen, L. V., Preminger, J. E., Jones, L., Nielsen, E., Oberg, M., et al. (2012). Hearing help-seeking and rehabilitation: perspectives of adults with hearing impairment. International Journal of Audiology, 51(2), 93-102. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2011.606284.

Lin, F. (2014). What are the consequences of hearing loss for older adults? Retrieved from https://www.linresearch.org/research.html

McKenna, L. (1987). Goal planning in audiological rehabilitation. British Journal of Audiology, 21(1), 5-11.

Noble, W., Jensen, N. S., Naylor, G., Bhullar, N., Akeroyd, M. A. (2013). A short form of the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing scale suitable for clinical use: The SSQ12. International Journal of Audiology, 52(6), 409-412. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.781278.

Palmer, C. V., Solodar, H. S., Hurley, W. R., Byrne, D. C., Williams, K. O. (2009). Self-perception of hearing ability as a strong predictor of hearing aid purchase. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 20(6), 341-347.

Preminger, J. E., & Laplante-Lévesque, A. (2014). Perceptions of age and brain in relation to hearing help-seeking and rehabilitation. Ear and Hearing, 35(1), 19-29. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31829c065c

Rogers, T., Milkman, K. L., Volpp, K. G. (2014). Commitment devices: Using initiatives to change behavior. Journal of the American Medical Association, 311(20), 2065-2066. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3485.

Topol, E. (2102). The creative destruction of medicine: How the digital revolution will create better health care. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Treacy, M., & Wiersema, F. (1997). The discipline of market leaders. New York, NY: Perseus Books.

Cite this content as:

Taylor, B. (2014, August). Ideas into action: Unbundling services and individualizing patient care. AudiologyOnline, Article 12871. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com