Nearly a decade ago, University of Memphis professor, Dr. Robyn Cox authored an article entitled, “Waiting for evidence-based practice for your hearing aid fittings? It’s here" (Cox, 2004). Since the publication of this article, numerous scholarly papers and national professional associations have advocated for audiologists to adopt best practice guidelines and/or evidence-based practice in the dispensing of hearing aids (AAA, 2006). An entire issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Audiology (JAAA) was devoted to this topic (2005, Volume 16, number 7). Many audiologists are still reticent to implement these procedures into their clinical routines. This statement is based upon recently published survey data suggesting that the majority of audiologists do not routinely conduct several procedures considered to be best practices (Mueller & Picou, 2010; Humes, 2012). There are several potential reasons for not conducting these recommended best practices, including time constraints, lack of financial resources to invest in the necessary equipment, and a general lack of training. Another possible reason for not implementing best practice guidelines may be a perceived lack of reimbursement associated with conducting many of these procedures (Taylor, 2009). In this case, the rationale is that there is not an obvious financial incentive to conduct many of the procedures outlined in best practice guidelines.

The purpose of this article is to show how audiologists can navigate and be financially successful in the current fee-for-service system by generating revenue for the tests, procedures, and services that are believed to lead to optimal patient outcomes by utilizing published best practice guidelines. We will use the example of an adult patient with hearing impairment. While many of the procedures outlined in this article are supported by evidence, this article is not intended to be a “best practice” recommendation. Rather, this article provides guidance on what tests contribute to the hearing assessment, hearing aid evaluation and selection, and hearing aid fitting and follow-up appointments based on published guidelines. In addition, this article outlines who can be held financially responsible for what item or service, and provides examples of what codes are appropriate to utilize to represent these specific items and services. We have broken the patient-provider interaction for audiologists who dispense hearing aids to adults into four distinct steps, which illustrate best practice and outcome driven procedures. Additionally, we illustrate what codes can be used to maximize reimbursement for these procedures. It is important to note that reimbursement is not exclusive to third-party reimbursement. Instead, reimbursement can come from the patient, the third-party payer, or any additional funding source.

What Clinical Procedures Constitute Best Practices?

The most readily available clinical guidelines pertaining to the audiologic management of adult hearing impairment were published in Audiology Today in 2006 (Volume 18, number 5, pp. 32-36). This guideline was created by an American Academy of Audiology (AAA) task force chaired by Dr. Michael Valente and contained 43 specific recommendations related to assessment, technical aspects of intervention, audiologic rehabilitation and assessment of outcomes. A systematic evidence-based review was used to create this guideline. Using established evidence-based practice (EBP) methods, the task force determined that less than a 1/3 of the recommendations within the published guideline were supported by Level 1-2 evidence, which is considered the highest quality of evidence in an EBP paradigm. Although this indicates that additional high quality studies are needed in the field of audiology to support the clinical decision making process, audiologists can be confident that this guideline represents current best clinical practices.

Under the assessment guidelines the following components are included:

- Comprehensive case history

- Measuring loudness discomfort levels (LDLs)

- Otoscopic inspection and cerumen management

- Determine need for referral or treatment by physician

- Counsel patient on the results

- Assessment of hearing aid candidacy and motivation toward amplification

- Determine medical clearance as determined by FDA (1977)

- Identify type and magnitude of hearing loss via pure tone, speech and immitance audiometry

- Auditory needs assessment utilizing a variety of questionnaires, including the following:

- Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB)

- Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI)

- Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE)

- Expected Consequences of Hearing Aid Ownership (ECHO)

- Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile (GHABP)

- International Outcome Inventory- Hearing (IOI-HA)

Under the technical aspects of intervention several items related to the hearing aid selection process, such as the selection of style, use of manually adjusted features, type of signal processing, number of memories and various other issues related to selection of advanced features are mentioned. In addition, several procedures related to quality control as well as objective fitting and verification procedures are summarized in the document.

Lastly, the 2006 guideline makes specific recommendations relative to instruction, orientation, counseling and follow-up. Although no specific outcome measurement process is referenced in the guideline, the authors emphasize the importance of conducting and documenting outcome measures in order to validate the fitting for the individual patient. For comprehensive review of these best practice guidelines, please refer to https://www.audiology.org/

Coding for Audiologic Best Practice Procedures

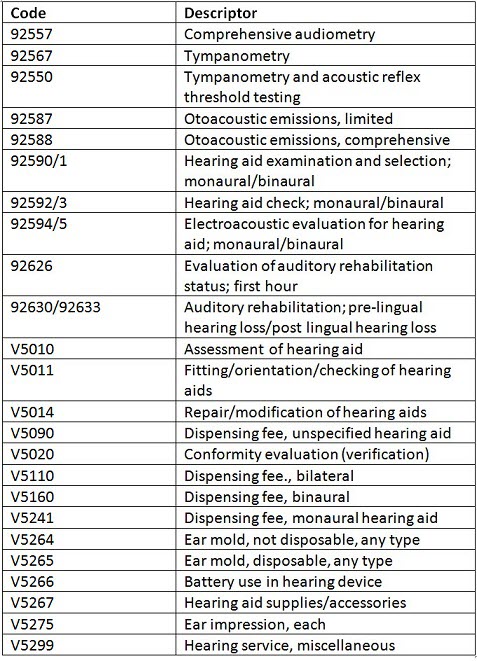

In order to appropriately code the processs and procedures that consitute audiological best practices, it is required to be familiar with the current CPT/HCPCS service codes that are the most commonly used to represent audiological and hearing aid services. Table 1 is a list of these codes along with a corresponding descriptor.

Table 1. CPT and HCPCS codes and descriptors for the most common audiological and hearing aid services.

Hearing assessment. Per the 2006 AAA guideline, the primary purpose of the hearing assessment is to appropriately identify the type and degree of hearing loss and rule out any medical or surgical conditions that could contraindicate hearing aid use and that warrant referral to a physician for an otologic evaluation. While published best practice guidelines should be used to develop your own comprehensive clinical protocol, it is important to remember that third-party payers do not cover the costs associated with any specific protocol. Instead, third-party payers typically only cover items or services that are deemed medically necessary to diagnose and/or treat a medical or surgical condition. It is important that audiologists read their managed care contracts and educate themselves on the coverage guidance and specifics for each payer. The hearing assessment test battery can include, but is not limited to, the following procedures and the use of the following codes. In addition, guidance as to the possible reimbursement for each code is provided.

- Air, bone, speech reception thresholds and speech recognition testing = 92557. This may be covered by a third-party payer when medically necessary, otherwise it is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Tympanometry and acoustic reflex thresholds = 92567 or 92550 (for both tympanometry and acoustic reflex threshold testing completed on the same patient if both completed on the same date of service). This may be covered by a third-party payer when medically necessary, otherwise it is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Acceptable Noise Level/most comfortable loudness level/uncomfortable loudness level = 92700. This is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Auditory memory (central auditory processing screening) = 92620-52. This may be covered by a third-party payer when medically necessary, otherwise it is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Otoacoustic emissions testing (with report and interpretation) = 92587 (limited; 3-11 distinct frequencies assessed per ear) or 92588 (comprehensive; 12 or more distinct frequencies assessed per ear). This may be covered by a third-party payer when medically necessary, otherwise it is the financial responsibility of the patient.

Hearing aid evaluation and selection. The hearing aid evaluation and selection is usually a separate appointment from the hearing assessment. The 2006 AAA guidelines suggest that in addition to conducting audiometric assessment, audiologists should be performing a thorough assessment of communication needs, lifestyle, expectations, motivation and self-perception of a hearing problem, as well as information & personal adjustment counseling. Several questionnaires, previously mentioned in this article were cited by the authors of the 2006 as possible choices in the hearing aid evaluation and selection process. In addition, according to other published review articles (Taylor, 2011), speech-in-noise testing should be conducted in order to evaluate a patient’s ability to understand speech in the presence of background noise.

Although audiologists are encouraged to conduct the hearing aid evaluation and selection procedures outlined in the previous paragraph, it is important that audiologists read and analyze each individual third-party payer contract and its associated fee schedule and to address, with the payer, specific codes or families of codes that are not mentioned or listed in the contract or fee schedule. Third-party payers address the hearing aid process differently. Many of these procedures are reimbursable, by either the patient or the third-party payer, when the following codes are used:

- Hearing aid evaluation and selection = 92590/1 or V5010. This is typically covered if the patient has a hearing aid benefit; otherwise this can be bundled into the cost of the hearing aid and/or is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Earmold impression, each (if applicable) = V5275. This is typically covered if the patient has a hearing aid benefit; otherwise this can be bundled into the cost of the hearing aid and/or is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Communication needs assessment and other questionnaires or inventories that evaluate satisfaction, motivation and perceived hearing handicap (e.g., COSI, HHIE, IOI-HA and/or ECHO = 92626. This is the financial responsibility of the patient; if this took less than 30 minutes of testing, add the -52 modifier to indicate a reduced service.

- Speech-in-Noise tests (e.g., Quick-SIN and/or HINT) included in 92626. This is paid privately by the patient; if testing took less than 30 minutes to conduct, add the -52 modifier to indicate a reduced service.

Hearing aid fitting. The 2006 AAA guidelines as well as other experts (Taylor & Mueller, 2011) suggest the routine use of probe microphone measures in order to verify an independently validated prescriptive fitting target (e.g., NAL-NL2). One recently published report indicates that verification of a prescriptive targets leads to a better outcome (higher self-perceived benefit) than a manufacturer’s first fit approach (Abrams, Chisholm, McManus, & McArdle, 2012). Other elements of a comprehensive hearing aid fitting protocol recommended in the 2006 AAA guidelines include electro-acoustic analysis and patient orientation to the instruments being fitted. It is very important that audiologists read and analyze each individual third-party payer contract and its associated fee schedule and address, with the payer, specific codes or families of codes that are not mentioned or listed in the contract or fee schedule. Third-party payers address the hearing aid process differently. There are several possible codes that can be used to bill for various tests and procedures that might be conducted during the hearing aid fitting appointment, such as:

- Electroacoustic analysis = 92594/5. Directional microphone test included in 92594/5. This code is typically covered if the patient has a hearing aid benefit; otherwise it can be bundled into the cost of the hearing aid and/or is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Fitting and orientation = V5011. This code is typically covered if the patient has a hearing aid benefit; otherwise it can be bundled into the cost of the aid or is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Dispensing fee = V5---. Aided loudness testing is included in V5020. This is often covered if the patient has a hearing aid benefit; otherwise it can be bundled into the cost of the heairng aid and/or is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Probe microphone verification = V5020. Aided loudness testing included is included in V5020. This is typically covered if the patient has a hearing aid benefit; otherwise it is bundled into the cost of the hearing aid and/or is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Auditory training/aural rehabilitation-individual or group/counseling = 92630/33. This is typically the financial responsibility of the patient unless specifically covered by the third-party payer.

- Earmold, custom, each (if applicable) = V5264. This is typically covered if the patient has a hearing aid benefit; otherwise it is bundled into the cost of the heairng aid and/or is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Mold/insert/dome, each (if applicable) = V5265. This is typically covered if the patient has a hearing aid benefit; otherwise it is bundled into the cost of the hearing aid and/or is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Battery, each = V5266. This is typically covered if the patient has a hearing aid benefit; otherwise it is bundled into the cost of the hearing aid or the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Hearing aid supply or accessory, each = V5267. This is typically the financial responsibility of the patient unless specifically covered by the third-party payer.

Hearing aid follow-up. The 2006 AAA evidence-based practice guidelines suggest that a successful hearing aid fitting include a plan for detailed and comprehensive follow-up care, including the use of counseling, auditory training and aural rehabilitation services. Many aspects of evidence-based follow-up care have codes and are reimbursable procedures, by either the patient or the third-party payer.

- Hearing aid check = 92592/3 or V5011. This is typically covered if the patient has a hearing aid benefit and the benefit has not been exhausted at the hearing aid fitting; otherwise it can be bundled into the cost of the hearing aid and/or is the financial responsibility of the patient.

- Hearing aid reprogramming (repair/modification of a hearing aid) = V5014. This is typically the financial responsibility of the patient unless specifically covered by the third-party payer.

- Auditory training/aural rehabilitation-individual or group/counseling = 92630/33. This is typically the financial responsibility of the patient unless specifically covered by the third-party payer.

Future Directions for Evidence-Based Care?

The implementation of evidence-based practice decision-making by audiologists when combined with their clinical experience and judgment is believed to minimize variability in outcomes and optimize patient benefit. Although the 2006 AAA best practice guidelines are comprehensive, additional higher levels of evidence are still needed. We are hopeful that AAA will reconvene this panel of audiologists to update this guideline with newly published, relevant evidence in the near future, and if so, the appropriate coding and reimbursement will vary accordingly. In the meantime, we believe this published standard represents the gold standard for high quality, evidence-based delivery of hearing aid services and have provided an example and guidance for maximizing reimbursement.

Summary

The primary objective of this article was to draw attention to the fact that evidence-based care can also produce a revenue stream, from either the third-party payer or the patient. Contrary to published claims (Taylor, 2009), we believe that audiologists have a financial incentive to conduct a comprehensive best practice protocol. It is the decision of the audiologists to decide if they want to pass these fees onto patients in a bundled or unbundled format, as there are advantages and disadvantages of each that are beyond the scope of this article. Finally, audiologists must continue to educate themselves on the codes and their appropriate uses and to integrate them and their associated cost into their hearing aid dispensing model and protocol. Research has shown that the use of a clinical protocol, largely based on a foundation of solid evidence improves patient performance, increases patient satisfaction and reduces hearing aid returns (Kochin, 2010). We believe it also can yield increases in revenue for the audiology practice.

References

Abrams, H.B., Chisholm, T.H., McManus, M., & McArdle, R. (2012). Initial-fit approach versus verified prescription: comparing self-perceived hearing aid benefit. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 23(10), 768-778.

Cox, R. (2004). Waiting for evidence-based practice for your hearing aid fittings? It’s here. Hearing Journal, 57(8), 10-17.

Cox, R.Special issue devoted to evidence-based practice. (2005). Journal of the Academy of Audiology. July-August. Guest Editor: Robyn Cox

Humes, L. (2012). Verification and validation : the chasm between protocol and practice. Hearing Journal, 65(3), 8-12.

Kochkin, S., Beck, D.L., Christensen, L.A., Compton-Conley, C., Fligor, B.J., Kricos, P.B.,...Turner, R.G. (2010). MarkeTrak VIII: The impact of the hearing healthcare professional on hearing aid user success. Hearing Review, 14(4), 12-34.

Mueller, H.G., & Picou, E. (2010). Survey examines popularity of real-ear probe-microphone measures. Hearing Journal, 63, 27-32.

Taylor, B. (2009). Survey of current business practices reveals opportunities for improvement. Hearing Journal, 62(9), 24-31.

Taylor, B. (2011). Using speech-in-noise testing to make better hearing aid selection decisions. AudiologyOnline, Article #832. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

Taylor, B., & Mueller, H. G. (2011). Fitting and dispensing hearing aids. San Diego: Plural Publishing Inc.

Cite this content as:

Taylor, B., & Cavitt, K. (2013, January). Evidence-based hearing aid dispensing practice: Financial incentives for audiologists. AudiologyOnline, Article #11520. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com/