Introduction

This is a transcript of an AudiologyOnline live webinar. Please download supplemental course materials.

This presentation is part of a series on various aspects of our hearing aid fitting process. Today I want to concentrate on the concept of satisfaction. This is a concept to which, as audiologists, we do not necessarily pay a lot of attention. Some of us do more than others, depending on orientation, work setting, et cetera. Satisfaction, when viewed from healthcare or other commercial industries, is a very big component of the evaluation in terms of the effect of intervention, treatment or purchase. I would like to spend a little time talking globally about satisfaction and then specifically get into some details of how the hearing aid fitting process can be modified to make sure that we are using a focus on satisfaction.

One of the best ways to start is by taking a look at the way we go about fitting hearing aids in general. If you step back from day-to-day practice and think globally about the way hearing aids are fit, we tend to use procedures that require us to measure things about the patient ahead of time, which will allow us to predict what we think should work well for the patient, and to fit and verify amplification based on those predictions. Many of our procedures are built around this model. It is what we use on a daily basis, and, in many ways, it is a very efficient way to work. The problem is that we spend a significant amount of clinical time with patients beyond that point. In other words, there are a significant number of patients where the fitting was not quite right, even after all the work and planning we did ahead of time. Because of this, we spend a significant amount of time in the follow-up phase, where that time is typically spent on fixing problems.

In my viewpoint, the problem is that we take the patient’s input rather grudgingly. We have a lot of confidence in our measurements, instruments and predictions in order to create a fitting. When that is not quite right and the patient wants something else, we go into this other phase that is not particularly well-defined in our field. When you think about that other phase, even right from the start, we tend to use very negative language in that phase. It is the fixing period. It is the problem-solving period. It is follow-up. These are terms that send the message to ourselves and to the patients that somehow the patient does not like what we did the first time. How dare the patient question the “Great and Powerful Oz” in all of us? We make a prediction and we think the patient should like it.

We tend not to view that follow-up in a very positive context. We do not talk about it as customization or personalization of the fit. We do not act as if we expect to have to modify anything from the original fitting that was somehow optimized for that patient in order to get to a final fitting. Hopefully I will be able to shift you from a “fixing” mindset to much more of a positive mindset, where the stages that follow the initial fitting as viewed as “customization” or “personalization.”

There are a few patients that are fit, left to go on about their lives and are never heard from again. A significant number of patients require some further intervention on the fitting. It is going to happen anyway, and we might as well think of that as something positive, designed to improve the satisfaction of the patient.

I am going to get a little philosophical for you. When you go through the literature on the psychology of design and why we design things the way we do (not just in the hearing aid field), one of the things to remember is that tools, including hearing aids tools, are expected to develop over time. The first shot at anything is never perfect. Humans expect tools to be further and further refined until they become optimized. The hammers that you buy today at the hardware store do not look like the hammers that were used by the cavemen. They have been developed and improved over time, and when things get better, they are assumed to be better.

Thinking of a hearing aid fitting as a tool that should evolve over time to get better and better is one way to put the hearing aid process in a very positive light. When you engage a patient into making choices about the way something is designed for them, or when you give them a role of customizing a fitting for them, there is actually a neurophysiological effect in which the neural tracks that convey positive aspects of an option become more entrenched, especially when the patient is able to verbalize a preference one way or the other. There is a neurophysiological basis for preference, where the more the patient expresses their preference, the more they like what they chose. It is a self-generating type of machinery, whereby asking the patient’s opinion and including the patient’s opinion in the next stage, the acceptance of that solution becomes even greater on the part of the patient.

Lessons from Other Professions

We are not the only profession that looks at satisfaction. There are many other professions, especially in the medically-related fields, where satisfaction is a key element to the way they evaluate their own processes. There is an abundance of literature in the field and a lot of focus on it. I am sure that you have noticed over the last decade or so that there is tremendous emphasis on patient satisfaction in the marketing of healthcare. Billboards immediately come to mind. This is not by accident. These healthcare industries have realized the economic impact of focusing on satisfaction.

I am going to make a couple of sweeping observations of some of the things that come out of that overall literature. One is that patient satisfaction has an interpersonal aspect to it. This means that patients have to feel that the professionals they are dealing with care about them as individuals. It is not just about being nice to a patient. It goes deeper, to the level whereby the course of treatment chosen for the patient is viewed as being developed based on knowledge about that individual’s needs and preferences. If the patient is given the opportunity to express what they want out of the process and they can see the healthcare provider taking those preferences into account, it significantly improves the overall satisfaction with the healthcare provider and with the outcome.

The second big observation is that the care environment matters. It is not enough just to be excellent at what you do. It is where the care is given and all the practical elements involved in that environment that matter and affect satisfaction, even down to practicalities like the cleanliness of bathrooms, ease of parking, friendliness of front office staff, et cetera. In our field, this is one thing to which we have paid more attention over the last decade or so. It is the notion that you have to get all the things right in your practice. Whether you are talking about a private practice audiologist or an audiologist working in a medical setting, the physical aspects and the practicalities of the environment affect the satisfaction. It is not just the care, but the entire care environment.

Fitting versus a Fitting Experience

This leads me to an important point: we need to differentiate between a good fitting and a good fitting experience. The patient, oftentimes, will not differentiate between the two. In other words, as an audiologist, you may do an excellent job of using technology to minimize the effects of sensorineural hearing loss for a patient. That, in my mind, is a very good fitting. But if there are aspects of the total experience that the patient has encountered that are not positive, then those are going to influence the patient’s assessment of the fitting. The quality of the audiology that you provide will be affected by whether or not it is easy to park at your facility. Although those things should logically be separate, patients do not always act logically. They are like kids, dogs, or spouses in that they do not always act in the most logical manner. Most of what I will be talking about today is going to be focused on getting the fitting to a point where it satisfies the patient. I want to make sure that we are clear that all the things that go into the fitting experience can affect the perception of how good the actual treatment is.

Acute Condition versus Chronic Disease

Mac Butts, who is a private practice audiologist in Richmond, Virginia, earlier this year provided responses in an article in the ASHA Leader (Oyler, 2012) about some of the things that he believes that we, as a field, could do better. One of things that he points out is that we should stop acting as if sensorineural hearing loss is an acute condition that we somehow cure. We need to do a better job of focusing on sensorineural hearing loss as a chronic disease that we help the patient manage. That is the simple reality of sensorineural hearing loss. We do not make sensorineural hearing loss go away in a patient. It is going to be there and might even get worse. This notion that we solve their hearing loss or make it go away is not true, but sometimes the actions we show suggest that is the case. Our job as a professional is to help the patient manage that situation. We cannot make the problem go away, but we can help the patient manage and cope with it through the use of technology, aural rehab, and other resources.

The reason I bring this up is that it goes back to the idea about satisfaction with the entire fitting experience. One part of the satisfaction element is that the patient sees this as something where you, as the professional, are helping them through a problem. This is a little different than the mindset of a first-time user and what they are expecting in an instant transformation. Those things are all true, but at the end of the day, this is a chronic disease, and the care that we wrap around our treatment is perceptible on the part of the patient. We should never forget that.

This brings up an interesting study that was reported over ten years ago by Cox and Alexander (2000) on benefit, satisfaction, and perception on the part of the patient. I want to walk you through this study, because it brings up a good point about the total fitting experience. This study looked at two questionnaires, one called the Satisfaction with Amplification in Daily Life (SADL) and one called the Expected Consequences of Hearing Aid Ownership (ECHO). The SADL is a classic sort of outcome measure, and the ECHO is a questionnaire developed to assess patient’s expectation before they enter the hearing aid process. The ECHO and the SADL are designed to be used as a pair so that the questions on the expectation are then assessed on the outcome.

Data in this study first looked at expectation compared to the outcome. This is a subset of the questionnaire that was related on the actual outcome of the fitting, or, in other words, whether or not the patient was doing better in matters of communication. What she noted was the classic situation where the expectations were higher than the outcome. Therefore, the expectation for outcome was higher than the patient was actually able to achieve. This is not new to any audiologist who has ever fit hearing aids. We know that patient’s expectations tend to be higher than the outcome.

What is very interesting was that, on another subset of the ECHO and SADL related to service and costs, such as whether or not the patient felt that they were cared for well or whether they feel they received a good value for what they got, we saw a different picture. The outcome was at least as good, if not better, than the expectation going in. In this study, it was nice that those expectations were able to be achieved.

This brings up an interesting difference between the fitting experience and the fitting itself. Because of the nature of sensorineural hearing loss, we are never going to solve hearing loss totally, but we certainly can create in the patient’s mind the sense that they were well taken care of and they received good care out of the process, whether or not their hearing loss is totally solved.

What Drives Satisfaction?

If we get back to this issue of satisfaction and again look outside of our industry a little, an important study over 10 years ago from Jackson et al. (2001) was looking at satisfaction from primary caregivers across a variety of different dimensions. The most important single driving factor of satisfaction in the healthcare context is whether or not the patient’s expectations have been met. If a patient has unmet expectations, meaning they went into the process hoping and assuming that something was going to happen and that did not happen (condition was not better, they were not talked to in the right way, or they were not assessed in the way they expected), satisfaction ratings get hit very severely. There is a strong relationship between expectations and satisfaction.

It is an important lesson for us to learn because our expectation of the fitting process is often very audiological. We expect to improve speech communication abilities in quiet and noise, for example. That is typically the way we think about what we are trying to get out of a fitting. If that is not in line with what the patient is expecting out of the fitting, then no matter how good the fitting is, satisfaction may very well be low because we are not meeting the agenda that the patient had when they walked in. If we talk about agendas and we ask what drives satisfaction, it is whatever the patient considers important. That may or may not be the same thing that the audiologist considers important. We may focus on the highest level of performance in quiet or in noise, which is a very legitimate audiological way to look at the fitting of hearing aids, but if that is not in line with what the patient expects going in, then there may be a problem with patient satisfaction. One of the major points that I want to make throughout this seminar is that satisfaction is defined by the patient. The expectations and desires that the patient has are what will drive satisfaction and at the end of the day, whether or not the patient feels satisfied, the patient sets up that criteria of what it is going to take to be satisfied.

One person who has spent decades looking at the issue of satisfaction is Sergei Kochkin with his MarkeTrak surveys. That has been a big part of the influence of what satisfaction is all about. I would like to take a look at some of the things we can learn about satisfaction from the most recent MarkeTrak survey, which is MarkeTrak VIII (Kochkin, 2010). One of the things he points out about the evolution of satisfaction is that it has gotten better over the years. This is historical data over a series of MarkeTrak studies that indicate the numbers of patients who are satisfied with their hearing aid fitting are increasing. Dr. Kochkin notes that he changed the scale responses in a way that gave an artificial blip to the numbers from 2000 to 2004. Those satisfaction numbers continue to rise from 2004 to 2008. Satisfaction ratings are even higher in patients who have been wearing their hearing aids a year or less. If you take a look at where we stand right now on first-time users of hearing aids, we are at 81% satisfaction. The question is whether or not that is good enough. Is it okay that four or five patients who get fit with new hearing aids are saying that they are either satisfied or very satisfied with their fitting? That is not a bad number, but it could be better. I will let you decide whether we are doing well enough as an industry and as a field or not. Overall satisfaction, in general, is good for what we are doing.

Factors correlated with Overall Satisfaction

Dr. Kochkin (2010) also ran an analysis of the factors that predict overall satisfaction. A rating of satisfied or very satisfied with the hearing aid fitting can be driven by a variety of different subfactors. In good analytical form, he looked at this in quite significant detail. The top-ten factors correlated with overall satisfaction were as follows:

- Overall benefit

- Clarity of sound

- Value

- Natural sound

- Reliability of the hearing aid

- Richness or fidelity of sound

- Use in noisy situations

- Ability to hear in small groups

- Comfort with loud sounds

- Sound of voice (occlusion)

I would like to point out that not all of these factors are performance based. More specifically, of the top 10 factors, only three of them are actually related to how well the patient is performing with the hearing aids. These include overall benefit, use in noisy situations, and ability to hear in small groups. From an audiological perspective, that is what we tend to focus on. We focus on how well the patient is communicating when they get fit with hearing aids. However, when you take a look at overall satisfaction, those are only three of the top 10 reasons why patients feel that they are satisfied with whatever happened to them. I think it is important for us to keep in mind that when you put this back into the patient’s perception of satisfaction, you will see a different picture than if you think in audiological terms.

If you look at factors that are related to sound quality or the seamlessness of the sound and also comfort, they make up five of the top 10 overall satisfaction factors. These factors are clarity, natural sound, richness or fidelity, comfort with loud sounds, and sound of voice (occlusion). Those are not necessarily dimensions that we jump to right away as audiologists. We do not typically include those in outcome measures. We usually only deal with those issues after the patient complains about them. This goes back to the negative sense of what some feel follow-up is all about: dealing with problems that patients bring up. The reality is that you see many factors on the list related to overall satisfaction, and these are things that go beyond whether or not they hear and understand speech better.

Another thing Kochkin (2010) points out is that the average number of patient visits is related to overall satisfaction, and the fewer visits the patient has to make in follow-up, the better the overall satisfaction. However, if you break that down in terms of whether or not the person who fit the hearing aids followed a certain procedure, you will see a significant increase in the number of visits that it takes to get the fitting right if neither verification or validation was done at the time of fitting or as a planned part of follow-up. Verification not only significantly decreases the number of follow-up visits, but it continues to decrease if both verification and validation are used.

There has been a lot of focus in our field on the impact of verification using real-ear measures on outcome, but validation has not been as well defined. We oftentimes do not know exactly what we want to validate. A recommendation I would make is that whatever validation is used should be done on the terms that the patient chooses. I will try to make that point throughout the rest of the lecture that in whatever you do, validate that the fitting is good. Verification is a technical issue and should be done. But in terms of validating whether or not the patient feels like this was a worthwhile fitting, I would strongly encourage you to put that validation in the hands of the patient. Let them decide what makes a good fitting for them.

Let’s look at a little more data. We conducted a large study at Oticon in 2010 of over 1,400 patients, roughly split between first-time users and experienced users from many different countries. There were a variety of questions we asked them. I would like to focus on one particular question that we used in this survey. I specifically want to focus on the difference between first-time users and experienced users, because this factors into the whole equation of trying to get the highest level of satisfaction.

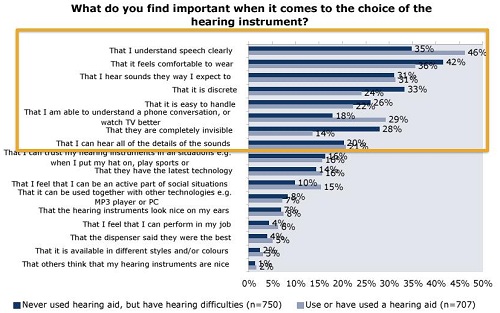

The question was, “What do you find important when it comes to the choice of the hearing instrument?” I would like to focus on the top six or seven responses on the part of the patient in places where a difference occurs between the first-time user and the experienced user (Figure 1). In the first answer, “That I understand speech clearly,” there is a significant difference between the first-time users and experienced users. The experienced users are more focused on this performance dimension than the first-time users. As you go through the other questions, the reason that the first-time users are not as focused on this is because they are focused on other things like cosmetics and comfort. The second answer, “That it feels comfortable to wear,” shows another significant difference. This is not as big of a concern with experienced users and first-time users, probably because they know that hearing aids can be made comfortable and are not as worried about it.

Figure 1. Oticon survey of first-time and experienced users. Dark blue bars represent first-time users; light blue represents experienced users.

One issue that comes up for first-time users is if the hearing aid is discrete and completely invisible. These are clearly cosmetic factors. What is important to first-timer users is different in many respects than what is important to experienced users. This should be factored into the assessment of what the hearing aid is doing for a patient or the way a patient feels about the hearing aid fitting.

Patient Mindset Entering the Process

Remember earlier that I talked about how important meeting expectations is in order to achieve the highest level of satisfaction, and that if expectations are left unmet, satisfaction will be harmed. The problem in the hearing aid field is sometimes the patient’s expectations are not well stated. In other words, the patient may have a mindset or set of expectations of what the hearing aid process will be like, both for first-time users and experienced users, but they are not necessarily well-described when the patient enters the process. Some patients are not good communicators. Oftentimes they are not asked the right questions. There are many reasons why this could be the case. Given the strong relationship between expectations and satisfaction, I think it is incumbent upon the audiologist to make sure that they are assessing what the patient’s expectations are right from the start.

You might not get this information from the basic questions that many audiologists ask. “What brought you here today?” “Why did you come to see me?” Asking those questions is not tapping into their expectations of a hearing aid fitting. That is something that has to be assessed in more detail than just the general opening statement that we often give. If a patient comes in with clearly unrealistic expectations or expectations that are in a different dimension than the audiologist is expecting, then the audiologist might not be doing a good job of meeting the expectations that the patient has. The patient is in the driver’s seat. They are the ones who are setting the agenda. The key is to make sure that the audiologist knows what that agenda is.

Motivation

The other issue I want to talk about is motivation. I want you to think back about the last time one of your loved ones made you go somewhere or do something that you really did not want to do. Let’s say you had to go see a chick flick or something like that. If you really do not want to be there and your motivation is poor, think of how you perceive all the negatives in that experience. The popcorn was soggy. The theater was not cool enough. It was too loud and the seats were squeaky. All the negatives of that experience are what stick in your mind because you do not want to be there.

On the other hand, if you are excited to be there, no matter what the negatives are, you do not notice them because you are motivated to be there. Obviously, motivation is a big part of what we have to deal with. Many first-time users have weak or poor motivation. They do not want to be getting hearing aids. This is something they have been putting off, maybe because of issues with aging or they are wary about the process. They may feel they are in this position because family members are making them. If that is the case, being able to achieve satisfaction in a patient with poor motivation is very difficult.

Before you start trying to convince a patient that the hearing aid fitting you created for them is the best possible thing they could get, you need to assess their enthusiasm. If they are not in a mindset to accept the positives, then it will be an uphill battle. I would remind you how dependent a patient’s evaluation of the fitting experience is based on their motivation. If you are concerned at all about motivation, you want to make sure that you are dealing with the motivation upfront. No matter how good the fitting is, if the patient does not want it, they are going to find all the negatives to it. If you do not want to deal with the negatives as part of the follow-up process, take a look at whether or not you are doing enough upfront to make sure their motivation is, at best, at least neutral.

Patient or Consumer?

I want you to answer the question, “Do you deal with patients or consumers?” This really depends on your work setting, but many audiologists will say they deal with patients. They wear a white coat, have an advanced degree and provide medical care. That is fine, and I am all in favor of a very positive, professional image of what we do. But in many ways, it does not matter what you think in terms of whether or not the patient is viewing this as a consumer interaction. It is not a black-and-white situation. Many patients who enter the hearing health-care process, even in non-commercial settings such as hospitals, may still see themselves as a consumer, because in many respects, they are. They are going to be asked to make decisions about buying something at different technology levels. No matter how much we like to not to think about that, it is one of the things that they do.

Again, the driver of this discussion environment is the patient. They are the ones who are ultimately making this decision. The notion of a consumer seeking satisfaction with their purchase is a very strong notion. Every time you buy something, you expect to be satisfied. If you are not satisfied, you want to do something about it. Just because the audiologist does not like to think of themselves as selling a product, the patient often sees it that way, and satisfaction from a consumer standpoint has to be part of the way you think about this process.

We do know that first-time users and experienced users have different agendas when they come in. For first-time users, we believe the agenda is appearance, acceptance, and performance, and in that order in many cases. In other words, first-time users are concerned about the way hearing aids look. Next, their initial exposure to amplified sounds has to be positive. They have to make sure that it is comfortable and that it sounds relatively natural. Then eventually they will be focused on performance. If you remember the data I showed earlier from the international patient survey (Figure 1), appearance and comfort are very high on the agenda, and it is not just performance, although as audiologists, we oftentimes like to think about performance.

On the flip side, experienced users are typically looking for things to be better. “Compared to what I am currently wearing, if I get a new set of hearing aids will things get better?” The meaning of better might be driven either by performance or by sound quality. Interestingly, performance is not something that they will be able to provide feedback about right at the fitting, but they will be able to give feedback about sound quality. Although an experienced user may be looking for better performance, they may quickly focus on sound quality because that is what they can tangibly experience at the fitting session. How well they perform with the device in the real world has to wait until they actually get there. Do not forget that sound quality might be what they are focused in on, so use it to your advantage. Most modern hearing aids sound better than older hearing aids. If you are fit with a hearing aid today, it will sound better than a hearing aid you were fit with five years ago. This is the evolution of technology.

Patient-Defined Dimensions

Moving away from the overall fitting experience, audiologists have ideas about what dimensions patients will focus on during the actual fitting. Audiologists might ask, “Are you hearing better? Are they helping you where you hoped they would be helping you?” Those are two very legitimate questions to which we want to know the answer. They are two common dimensions that a patient might have, but they are not necessarily the only dimensions that the patient might have.

Other patient-defined dimensions can include questions such as, “Does it sound like you expect? Is it natural sounding? Is it comfortable when you are in noisy environments? Are you overwhelmed by the sound? Does it seem unnatural? Does it sound clear and pleasant?” There are many ways that the patient could be judging the fitting. These other ways tend to focus on what I describe as sound quality or seamlessness or clarity. However, they are more of the nonclinical measures of the effect of a fitting. I like to use the term “aesthetics.” Aesthetics is a real thing for patients because how it looks, feels, and, more specifically, how it sounds becomes very important. This is what the patient can experience immediately at the time of the fitting. This may fill up the consciousness of the patient and what they become focused on because they are experiencing it at the fitting. They cannot tell whether or not the hearing aids are helping out in real environments until they are out there, but they can tell how the hearing aids sound. This has to be factored into the whole process.

Getting the Sound Right

Let’s talk about what it takes to get the sound right. I want to remind you that you make a decision that affects what the patient experiences 16 hours a day, every day of their life. This means that the way the hearing aid sounds is the new way that sounds sound to them. As a professional, you are creating a new universe for them. This is a universe that they experience all of their waking hours, assuming they are wearing their hearing aids. Getting the sound of the hearing aid right is more important than we suggest in our field. We tend to think in terms of the performance of the hearing aid and how well the patient can perform with technology. That is important, but having the hearing aid sound good is also important.

I would like for you to listen to some sound samples. You will hear Choice A and Choice B. There are three parts to these samples: Conversation in a café, music, and then conversation in the car. I would like for you to think about which one sounds the way you would want it to.

Choice AChoice BDid you like the first sample or the second sample better? I want to point out that this is a difficult task, because it relies on auditory memory to be able to remember what you heard and make a comparison. If you are anything like the other groups I have used these sound samples with in the recent past, some of you like the first one and some of you like the second. That is fine, because people have differences in what sounds good to them. This goes back to the notion that you are deciding for the patient what sounds will sound like to them for the rest of their life. The process of asking them what sounds better, one or two, goes a long way to create a sound with which they are going to be happy.

Variability of Sound Preference

Variability of perception is something that just happens. People hear things differently, much like having different taste and visual preferences. There is no reason why this should not be brought up in the process, specifically since patients like to be asked their opinion. Asking for their preference on the way it sounds helps to improve satisfaction. When you look at any measure of auditory performance in sensorineural hearing-impaired ears, such as the difference limen for frequency or word recognition performance in noise, one thing that you can observe over and over is how variable perception is. Some patients have sound preferences, performances or abilities that work one way or another way. This variability of function within the hearing-impaired population is just something that happens.

I want to spend a few minutes talking about the idea of achieving fitting targets. Oftentimes, we work as if hearing aid fitting targets are the key to getting good perception out of a hearing aid. I want to point out that this is not necessarily the case. One thing you should remember is that most fitting targets, especially NAL-NL2, are based on loudness perception models. They assume a typical relationship between hearing threshold and loudness perception. Perception, however, varies markedly from patient to patient. A fitting target based on a normative assumption about how loud sound is, like the NAL strategies, does not necessarily account for the typical range of variability around predicted loudness perception. Getting that target exactly right might not be as precise as we would like to pretend.

A study performed in the Netherlands a while ago (Van Buuren, Festen & Plomp, 1995) looked at 25 different frequency responses per patient, varying the gain in the low frequencies and the high frequencies. They tested the patient’s speech understanding in noise. What we noticed on a speech-understanding-in-noise test like this where a lower score is better, was that most of the scores came within one dB or so of each other in terms of how well the patient performed. It is only when you get to situations where you get a lot of low-frequency response and not a lot of high-frequency response that you start to see speech understanding in noise start to decline. Beyond that specific condition, there are a broad range of conditions in which the patient does fairly well, meaning that there is not one special spot where the frequency response has to be in order for a patient to do well on a speech-understanding test.

For the same listeners under the same conditions, the investigators (Van Buuren, Festen & Plomp, 1995) asked about the dimensions of clearness and pleasantness. This is where we start to see more variation in terms of what patients would report as being very pleasant or very clear versus not so pleasant or not so clear. If you focus on creating the response based on a performance measure like speech understanding in noise, then there are many performance measures that are going to achieve that goal. However, if you want to see variation between settings, you have to go beyond something as specific as speech understanding in noise, and go to more subjective or aesthetic-based questions. In fact, we tend to break it down into the difference between aesthetics and performance; there are some dimensions that are related to subjective qualities of the fitting that the patient relates to, and some are related to how well the fitting allows the patient to perform on specific speech understanding tasks.

Fine Tuning: Aesthetics versus Performance

One of the things we often talked about in the old days was whether or not the hearing aid sounded good to a patient. If it sounded “good,” we knew that it was working well for the patient or that they would get used to it. We thought there was trade-off between what sounded good and what was comfortable to a patient versus what was necessary for good performance. That trade-off does not exist in our field anymore. We do a much better job of managing the broad range of input intensities and complexities so that we do not have to have this trade-off. You are not going to hear a patient say, “I hate the way a hearing aid sounds, but it seems to work for me.” You do not expect something to not be appealing and still work for you. The expectation is that it should both sound good and do the job that you want. This is the way we have to work. This one of those things you have to assess if you want to make sure that the patient’s input is put into the process, because you are trying to maximize satisfaction. This is why I would make the case that you do have to focus on the aesthetics, because you are doing a cross-check of how well the hearing aid is being accepted on the part of the patient. This will go hand-in-hand with good performance in most cases and will be more immediate and more perceptible on the part of the patient. They will report this back to you in a relatively specific way.

It is important that hearing aid technology works well for a patient. When you do talk about performance, you have to distinguish in your mind whether or not the patient is focusing on overall performance or performance in specific situations; some patients can be more specific than others. It relates back, again, to their expectations. Did the patient enter the process because they were hoping they would hear better overall, or did they enter the process because there were some specific key situations in which they wanted to perform better? If their satisfaction is going to be related to met or unmet expectations, then you want to know what they seem to be centering on. This is how you want to focus the discussion and customization of the hearing aid.

One of the reasons it becomes specific is that overall performance is very difficult to assess in the office or clinic. Again, this is not something the patient would know until they go out into real situations. Even if the patient is focused on key situations, it is difficult to assume that you can recreate those situations in the testing environment. This is why you may want to focus your follow-up much more on the aesthetics than performance because it is something that is a little easier to create in the testing environment.

If we talk about aesthetics versus performance and assess aesthetics in the testing environment, there are a variety of things that have to be considered. First of all, you must have an idea of what sounds you want to use, which questions you want to ask and which device dimensions on which you are going to be focusing. The problem here is that you have three moving parts. It can be confusing as to whether or not you are using the right sounds, asking the right questions, and focusing on the right adjustments in the product in order to make the sound right for the patient. Also, you might have more than one dimension that the patient is focusing on, and they can focus on those dimensions in different weights of importance. One of the very first things that you want to do to get the fit right for the patient is to make sure you have a clear plan in your mind about what you are going to assess; make that plan clear to the patient. If the patient is confused about what you are asking and what they are listening to, then it can become an even bigger process. Getting clarity in this process becomes very important.

Patients can easily make decisions between this or that. Earlier, I gave you the option of listening to choice A or B and choosing the one you liked. Many patients can do this, especially if you have a very tight time limit between A versus B and if you can present it multiple times. It becomes easy to make that decision. This will be driven by the fitting software you are working with, and whether or not making those changes and having the patient listen to them immediately is a good thing. In general, patients are not going to be very specific about the good dimensions, but they tend to be more specific about what they do not like in the fitting. If something sounds good, it probably sounds good overall. If it does not sound good, the patient is more likely to bring it up. You might not know what that specific negative issue is until you ask them. One of the best questions to ask in follow-up is, “What do you notice about the sound?” When you ask this question and you give them time to be specific, they will probably bring up very specific things, some positive and some negative. You want to focus on minimizing those negatives.

Many people have looked into sound quality over the years. If you are looking for one specific question in regard to aesthetics that is strongly related to overall sound quality, it would be about clarity. Patients seem to be able to understand what the term clarity means, so this is a good question to ask. This needs to be better defined by our field, and more work will be done in this area.

Summary

Our focus should be on turning the follow-up process from a negative to a positive. We spend so much time trying to fix problems and problem-solve for our patients. I firmly believe if we can turn this more into a customization session or individualization session that is a positive experience, we can change the tenor of hearing aid fittings. The process does not have to be as negative as it sometimes feels for patients.

If I were to summarize the points I want to make in order to maximize satisfaction on the part of the patient, first and foremost, the total experience matters. Satisfaction is not just how good the fitting is, but also all the experiential things that go into. I would encourage you to uncover the expectations of your patients, because expectations are strongly related to outcome of satisfaction. You want to make sure that you understand what the patient’s expectations are going into the process. You also want to assess motivation. If the motivation is weak or poor, you will need to put some work into that before you can expect to move on. Poor motivation will kill satisfaction ratings each and every time.

You are going to be focused on performance in both specific and overall listening aspects, but almost more importantly for many patients are sound quality, comfort and seamlessness. All those aesthetic dimensions matter to a lot of patients. You want to make sure that you maximize the fitting in that area.

Finally, predictions are difficult. Making predictions about what should work for a patient ahead of time has always plagued our field. We are not very good at it. If we can change our approach and mindset to be less dependent on making predictions about what a patient should want and become more focused on doing a planned customization of the fitting based on the dimensions that are important to the patient, we can then achieve even higher levels of satisfaction.

References

Cox, R. M. & Alexander, G. C. (2000) "Measured satisfaction: What does it tell us?" Invited paper presented at the International Hearing Aid Research Conference, Lake Tahoe, CA.

Jackson, J. L., Chamberlin, J., & Kroenke, K. (2001). Predictors of patient satisfaction. Social Science and Medicine, 52, 609-620.

Kochkin, S. (2010). MarketTrak VIII: consumer satisfaction with hearing aids is slowly increasing. The Hearing Journal, 63(1), 19-20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30-32.

Oyler, A. (2012). The American hearing loss epidemic: few of 46 million with hearing loss seek treatment. The ASHA Leader. Retrieved from https://www.asha.org/

Van Buuren, R. A., Festen, J. M., & Plomp, R. (1995). Evaluation of a wide range of amplitude-frequency responses for the hearing impaired. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 38(1), 211-221.

Cite this content as:

Schum, D.J. (2012, November). Does the fitting satisfy the patient? AudiologyOnline, Article 11426. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com