Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the webinar, Delivering Culturally Competent Care: Strategies for Clinicians, presented by Kathleen Weissberg, OTD, OTR/L.

Learning Objectives

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Define cultural and linguistic competency.

- List cultural and social factors that may have an impact on a patient's experience of illness.

- Describe factors that affect a therapist's ability to provide culturally and linguistically competent care

Introduction and Overview

During this course, we are going to define cultural and linguistic competency. I will shorten that to “cultural competency” throughout the rest of the session rather than saying the longer full phrase, “cultural and linguistic competency.” We will discuss cultural and social factors that may have an impact on a patient's experience of illness. Finally, I will describe factors that affect a therapist's ability to provide culturally and linguistically competent care.

Definitions and Terminology

We continue to have concerns about disparities in healthcare and the need for healthcare systems to accommodate increasingly diverse patient populations. Cultural and linguistic competency has become more a matter of national concern.

Cultural and linguistic competency. But what is cultural and linguistic competency? Cultural and linguistic competency can be defined as “the capacity for individuals and organizations to work and communicate effectively in cross-cultural situations.” This capacity is supported through policy, structures, practices, procedures, and dedicated resources that take into account and are responsive to diverse populations, cultures and languages.

The cultural and linguistic differences between you and your patients can result in miscommunication, a lack of understanding regarding their diagnosis or their treatment, and other consequences that can negatively affect their health outcomes. Developing cultural competency can help you to minimize communication errors, increase your understanding, and overcome barriers that may affect the care you are providing to your patients. Also, cultural competency includes increasing your awareness of communities and their perspectives, and becoming more self-aware of your own personal attitudes, beliefs, biases and behaviors that can impact your patient care. This can help you improve your patients’ quality of care, their access to care, and certainly, their health outcomes.

Culture. Culture is the integrated pattern of thoughts, communication, actions, customs, beliefs, values, and institutions associated wholly or partly with racial, ethnic or linguistic groups as well as religious, spiritual, biological, geographical, or sociological characteristics. That is quite a mouthful. Culture is dynamic in nature, and an individual may identify with multiple cultures over the course of his or her lifetime. As we said, cultural competency is that capacity for individuals - and organizations as well - to work with and communicate effectively in cross-cultural situations.

Culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS). Culturally and linguistically appropriate services are services that are respectful of and responsive to individual cultural health beliefs, practices, preferred languages, health literacy levels and communication needs. These include any services employed by all members of an organization, regardless of size.

In the handouts, I have included the National Standards for Culturally Competent Care; those are the CLAS standards. We are not going to review them in this course, but they are the guidelines for culturally competent care in various organizations.

Persons with Limited English Proficiency (LEP). These are individuals who are unable to communicate effectively in English, and may have difficulty reading or writing in English. Limited English Proficiency refers to a level of proficiency that is insufficient to ensure equal access to services without language assistance.

Health. Health encompasses many different aspects: physical, mental, social, spiritual and the like.

Health disparities. Health disparities are a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with disadvantages. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have greater obstacles based on their racial or ethnic group, their religion, their socioeconomic status, their gender, age, mental health, physical disability, sexual orientation, etc. These are characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.

Healthcare disparities. Healthcare disparities are differences in the receipt of, experiences with, and quality of healthcare that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, but rather to some of those other types of issues that we just discussed.

Other Definitions of Culture

There are obviously other definitions of culture:

- “A culture, in the anthropological sense, is the set of beliefs, rules of behavior, and customary behaviors maintained, practiced, and transmitted in a given society. Different cultures may be found in a society as a whole or in its segments, for example, in its ethnics groups or social classes.” (Hahn, 1995)

- “The cluster of learned and shared beliefs, values (enrichment, individualism, collectivism, etc.), practices (rituals and ceremonies), behaviors (roles, customs, traditions, etc.), symbols (institutions, language, ideas, objects, and artifacts), and attitudes (moral, political, religious) that are characteristic of a particular group of people and that are communicated from one generation to another.” (Gardiner & Kosmitzki, 2005)

What is Culture?

So again, what is culture? Well, culture is learned, as we just said. It is transmitted from one generation to the next. You learn culture through interactions with others; by listening to, by observing, and assessing those interactions within your own family network.

Culture is localized. It is from those interactions that you identify and learn what defines the cultural universe that you share with other members of your society. Those meaningful elements are shared by some, but not everyone, within that society. We need to recognize the difference; the fact that some in a community may share in these elements, while others do not.

Culture is patterned. Patterning is essential for social behavior and the creation and maintenance of a society. It is essential for individuals within a group to develop patterns of behavior that minimize ambiguity and help them to avoid having to renegotiate every social interaction that arises.

Culture confers and expresses values. Values define concepts and behaviors that are important to that cultural system. Those values are embedded in the culture and in the individual behavioral decisions and choices.

Finally, culture is persistent but adaptive. So it is stable, but it also adapts. The cultural knowledge of an individual will continue to change over his life course as he encounters new objects, new situations, and different things in his environment. Those experiences will shape each individual person.

Why is Cultural Competence Important?

Culture shapes our language, our behaviors, our values, and our institutions, and delivering care in a culturally appropriate manner is a key way to help improve quality of care for diverse patients. Culturally appropriate services are shown to improve quality, increase patient safety, and definitely boost patient satisfaction.

Demographic Changes

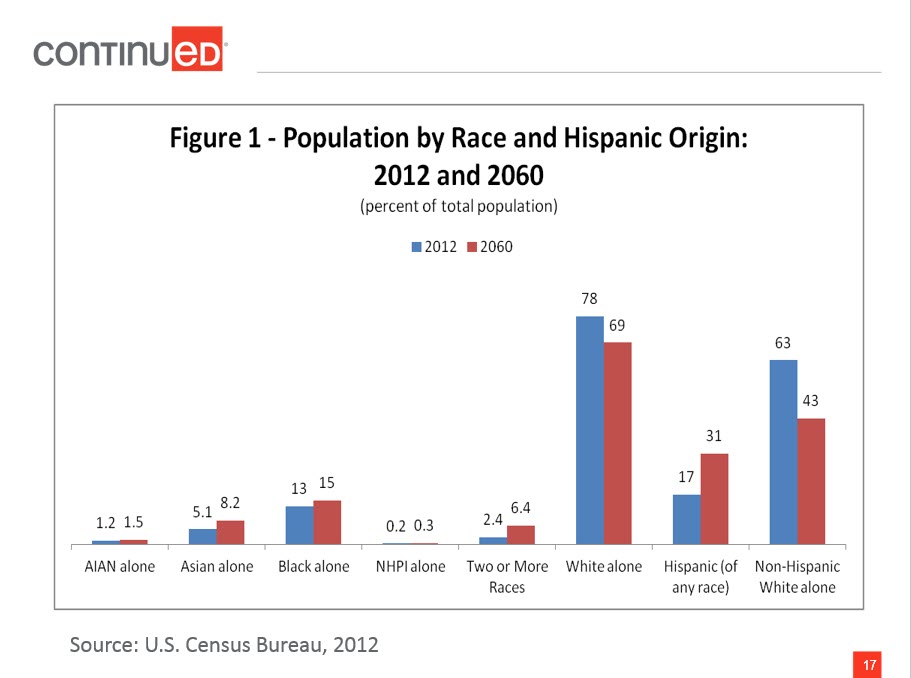

The United States has experienced increased cultural and linguistic diversity over the last several decades. The United States Census Bureau projects that by 2060, the United States will become an even more multicultural society. Demographic changes within the healthcare workforce, however, have not kept pace with society as a whole. About 70% of the allied health workforce is white/non-Hispanic, and because of that, cultural competency takes on a whole new level of importance. Workforce diversity can lessen that cultural gap that might exist between the provider, and the patient coming from a different background.

You can see in Figure 1 the anticipated demographic changes.

Figure 1. Population by race and Hispanic origin: 2012 and 2060.

From 2012 to 2060, white non-Hispanics will remain the largest single group, but will no longer be a majority. Thomas Mesenbourg from the US Census Bureau said, "The next half-century marks key points in continuing trends. The United States will become a plurality nation where the non-Hispanic white population remains the largest single group, but no group is in the majority. As the US increasingly becomes a more multiethnic, pluralistic, and linguistically diverse society, the possibilities for misunderstandings, mixed messages and errors in communication are inevitable. To address and/or prevent these disruptive factors while delivering care, cultural competence and sensitivity must be added to the knowledge and skills needed for therapy practice in the future." That is a direct quote.

Health and Healthcare Disparities

There are two reports that come out every year from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). These are called the National Healthcare Disparities Report and the Health Disparities and Inequalities Report, respectively. What is important about those reports is that they list contributing factors toward the persistence of health and healthcare disparities. Here are examples:

- Social determinants of health

- Lifestyle choices

- Patients’ care-seeking behavior

- Linguistic barriers

- Variations in the predisposition to seeking timely care

- Degree of trust

- Ability to pay for care

- Location, management, and delivery of health care services

- Clinical uncertainty

- Beliefs of health care practitioners

Social determinants of health - including education, income, or access to healthy food - is a contributing factor, as are lifestyle choices, the degree of trust that we might have in a care provider, and the ability to pay for care, whether directly or through insurance coverage. Even the beliefs of healthcare practitioners can factor in.

The health and healthcare disparities are well documented across many different cultural and linguistic groups. Individuals of different races, members of the lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender (LGBT) community, individuals with physical disabilities, and individuals in rural areas all may experience health and healthcare disparities at some point during their lifetimes.

Examples of healthcare disparities include the fact that racial and ethnic minorities experience disproportionately higher rates of chronic disease and disability, higher mortality rates, and lower quality of care compared to non-Hispanic whites. Suicide is the third leading cause of death among youth ages 15 to 24, and LGBT youth are more likely to attempt suicide when compared with their heterosexual peers. Individuals with lower incomes are more likely to experience preventable hospitalizations, compared to individuals with higher incomes.

Why Cultural Competency Matters

Again, delivering care and services in a culturally appropriate manner is one way that you can help to address health and healthcare disparities. Why does it matter? As I said earlier, culturally appropriate services are respectful of and responsive to individual cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy levels, and communication needs employed by all members of an organization. In healthcare settings, culture and language differences can result in misunderstanding, lack of compliance to the plan of care that you have established, and other factors that can negatively influence the clinical situation. Providing culturally appropriate care is especially urgent, because research has shown that many cultural groups receive lower quality healthcare even when all of the other factors (e.g., socioeconomic or access) are controlled. Remember that cultural groups are not just racial or ethnic or linguistic, but can be religious, spiritual, biological, geographical, and can also include those who have limited English proficiency, limited literacy skills, or those who are deaf or hard of hearing.

Terminology

We will talk more about this, but bias, stereotyping and prejudice can also contribute to healthcare disparities. Let's look at those terms in a little more detail.

- Bias: Bias is a preference or an inclination, especially one that inhibits impartial judgment. It could also mean an unfair act or policy stemming from prejudice.

- Assumption: An assumption is just that; it is an underlying assumption and an unconscious, taken-for-granted belief and value that helps determine behavior, perception and thoughts.

- Prejudice: Prejudice is a negative attitude toward a specific group of people.

- Stereotype: A stereotype is an oversimplified conception, opinion or belief about some aspect of an individual or a group of people.

- Discrimination: Discrimination involves actions that deny equal treatment to persons perceived to be members of some social category or group.

Everyone has biases. We all make assumptions about things and about other people. Those biases and those assumptions only become problems when they result in prejudicial or unfair treatment or discrimination, particularly when it involves the clinic setting.

Why Competency Matters

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommends that we adopt as our explicit purpose to continually reduce the burden of illness, injury and disability, and to improve health and health function. To reach that goal, we should aim to provide healthcare that is, first of all, safe, so as to avoid injuries from any of the care that is intended to help them. Care also needs to be effective, and based on scientific knowledge or the best available evidence. We must give the services to those who would benefit and refrain from providing services to those who would not benefit; in other words, we need to avoid overuse and underuse.

Care should be patient-centered, so it is respectful and takes into account patient preferences, needs and values. It needs to be timely, so as to reduce waits and sometimes harmful delays for those who need it. It should be efficient, avoiding waste of equipment or supplies or energy. Lastly, it must be equitable. The care we provide to our patients must not vary in quality because of gender, ethnicity, geographic location, or anything else.

Factors Affecting Competency

Self-Awareness

Let’s look at some of the factors that may affect competency, beginning with self-awareness. Awareness of your own values and those of the healthcare system in which you work is the foundation of culturally competent care. We are going to talk about some more definitions, such as ethnocentrism, essentialism, and power differences. Those can all affect your ability to provide culturally sensitive and appropriate care. Those beliefs could be very much conscious beliefs, or they could be unconscious beliefs based on your background, ethnicity, culture, and upbringing.

Ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism is a belief that “My way of life and my view of the world are inherently superior to, and more desirable than, anybody else’s.” In healthcare, this could prevent you, as the therapist, from working effectively with a patient who has beliefs or a culture different from your own, and that does not match your own ethnocentric worldview. When we don’t address ethnocentrism, it can compromise that patient-therapist relationship and lead to mistreatment, insufficient treatment, or, in extreme cases, abuse.

Essentialism

Essentialism defines groups as “essentially” different, with characteristics that are “natural” to a group. It means believing that all folks in a particular group are one way; it is almost like labeling, if you will. Essentialism does not take into account any sort of variation within a culture. If we believe in essentialism, it can lead us to stereotyping. In doing so, your treatment would focus on your beliefs about a larger group, rather than taking into account that each individual may have his/her own preferences or values.

Power Differences

Then there are power differences. You may not realize that these are there, but they are. These reflect the power imbalance in patient-provider relationships. Individuals with power may not even be aware of its daily effects. You may think that maybe you don’t have power as the therapist, but you do. In that relationship with your patient, you are seen to have power. Some cultural groups may feel powerless, quite frankly, when faced with institutionalized racism or other forms of privilege enjoyed by a dominant group. Without being aware of power differences and their effects, you as a therapist can perpetuate healthcare disparities.

What we need to do is specifically learn about a patient's “truth,” if you will, that is formed by their culture, language, experience, history, and sources of care, and then try to integrate that. Every one of your patients will come to you with his or her own truth, and it is up to you to try to uncover what that is, and what their perceptions are. You may have some stereotypes about patients from various cultural or linguistic backgrounds. Some therapists may impose beliefs in their health system that contradict the beliefs of their patients. Our ways of speaking, such as speaking louder or speaking slower in an exaggerated way, may transmit biased attitudes more visibly than the spoken message. Even nonverbal, like your posture and mannerisms, may demonstrate that you have a stereotype, or convey a stereotype to your patient that you are not aware of.

Positive Effects on Patients

As much as possible, it is really important to take cultural values and language into consideration when developing a care plan and delivering care because that positively impacts care, outcomes, quality, compliance, and satisfaction. When we can tailor our program to the individual needs of clients, their backgrounds, and their perceptions of illness, carryover and compliance are dramatically improved. Patients will benefit when we learn more about their cultures and become confident in our ability to care for diverse groups, and the research shows that patients are more satisfied with their healthcare interactions and they adhere to their treatment recommendations even more.

Factors with Negative Impact

There are factors with a negative impact. We have already reviewed these, but again, you have to understand where you are coming from. Self-assessment is so important because your bias, your discrimination, your ethnocentrism, your essentialism, your power differences will definitely have a negative impact on your care.

Self-Assessment Tools

Self-assessment tools can help you learn about your own assumptions, your biases, and your stereotypes. You might be thinking, "I do not have any of those; I treat everybody the same." That is actually not always a good thing because it does not take into account individual differences in our patients.

There are many self-assessment tools available in the public domain. I particularly like a tool published by Tawara Goode in 2009. It is listed in the references and it is a checklist related to promoting cultural and linguistic competency. It is a bit on the older side, but I think it is still really good. It looks at your values, your attitudes, the environment that you are working in, and your communication style.

Importance of Self-Assessment

The importance of a self-assessment tool like this is that it is a step in the process of improving your cultural competency. Awareness of your beliefs and attitudes will help to make sure that you are not providing inequitable care to patients based on assumptions, biases and stereotypes. Be aware of that, and treat your patients based on their perception of illness, not your own. I cannot stress enough that you need to examine this. If you don’t, it could lead to differential care or preferential treatment of some individuals. Stereotypes and biases are not isolated; they are closely related to how you have been socialized by your own group and by your provider culture.

Again, there are a lot of different tools available. The important piece is that you find one and do your own self-assessment.

Along with those self-assessments, there are many different tools in the public domain for organizational assessment. You may have already done this for yourself and are very self-aware but maybe your organization has not. Your organization needs to look at the printed materials that they are delivering; their posters that are in the community or the different pamphlets they make available. We want to make sure that the community we work in is equally aware.

Models for Becoming Culturally Aware

How do you become more culturally aware? There are two models of care I am going to describe that address assessment or becoming more culturally aware.

Campinha-Bacote Culturally Competent Model of Care

The first one is the Campinha-Bacote Model of Care. It uses the “ASKED” mnemonic, related to five questions that helps you assess your level of cultural competency:

- Awareness

- Are you aware of your biases and the presence of racism?

- Skill

- Do you know how to conduct a cultural assessment in a sensitive manner?

- Knowledge

- Do you know about different cultures’ worldviews and the field of bio-cultural ecology?

- Encounters

- How many face-to-face interactions and other encounters have you had with people from different cultures?

- Desire

- Do you “want to” become culturally and linguistically competent?

Purnell Model for Cultural Competence

The next one is the Purnell Model for Cultural Competence. This one is great because it goes through many different domains of cultural competence. If you ever see this one played out, it looks like a bull's-eye. I am not going to read everything that is on the slides, but it first looks at the overview or the heritage of that person. Why did she immigrate here? What is her educational status? What is her occupation? How does all of that play into her view of health?

Communication is contextual use of language, and can be either verbal and/or nonverbal. It includes voice, volume, tone, and intonation. I come from a culture at home where everyone seems to be a loud talker. My husband always asks, "Why are they yelling at us?" But that is just how we are. Communication can include how we use our names, and what name a person prefers to be called. In other words, do you want to be called by your surname, or by your first name? In addition, eye contact and body language are obviously very important.

Family roles are very important. What is the role of the head of the household? Can that be a female, or does it have to be a male? What are the developmental tasks of children? What are their child-rearing practices? What are the roles of the aged and extended family members? Oftentimes in our clinical care, we deal with just the spouse, but maybe we also need to look at the extended family. There are workforce issues that we can look at as well.

I just used the term “biocultural ecology” with the other model; it has to do with looking at variations in skin color, physical differences in body stature, genetic, endemic and topographical diseases, and how the body metabolizes medications.

We should examine high-risk behaviors because some cultures may have riskier behaviors than others. This includes non-use of safety measures such as seat belts or helmets, or high-risk sexual practices.

Nutrition is another area. What meaning is given to food? What are their food choices, their rituals, and their taboos? How is food used during illness? How do they use food for health promotion and wellness?

Here are a few other aspects related to cultural competence. Pregnancy is an issue that we would look at. Death rituals include things such as bereavement behaviors and burial practices. Spirituality involves the behaviors that give meaning to life, and individual sources of strength.

As for healthcare practices, we would ask, what is the individual responsibility for health? What are their self-medicating practices? What are their views toward mental illness, organ transplantation, or organ donation? In addition, we look at their views of healthcare practitioners. What is the status, the use, the perception of traditional healthcare providers, healthcare plans, and healthcare settings?

These are all different areas that we want to look at to do a true cultural assessment. Do you need to go through a checklist of all of these? Of course not, but these are the things that we may want to try to uncover by simply asking our patients, "Tell me a little bit about you. Tell me about your family."

An Ongoing Process

The other thing to recognize when looking at cultural competence is that competency development is an ongoing process. Only over time are you going to promote understanding and skills for developing and delivering this type of care. The more you develop competency through repeated practice, the better you will recognize your own assumptions and your biases. Remember that the ability to understand yourself is the starting point for integrating any of that new knowledge about other cultures.

Understanding the Health-Related Experience

Disease vs. Illness

As we look at other cultures, it is important to look at the health-related experience. There is definitely a distinction between disease and illness that is important to understand when we are providing culturally competent care. Disease refers to physiological and psychological processes. Illness refers to the psychosocial meaning and experiences of the perceived disease for that individual, the family, and those who are associated with that individual, which might include external or extended family.

Individuals seek healthcare because of their experience with illness, but we are primarily trained to treat disease. A disconnect can result from providing something for the disease, when the patient's need is for treatment of the illness. These are two different concepts, and that can be a very significant issue in cross-cultural encounters. A culturally and linguistically competent therapist would address both a patient's disease and his or her perception of illness.

Gaining that understanding of the patient’s perception of illness is extremely valuable. For example, some cultures consider the onset of Alzheimer's disease or diabetes or hypertension as just part of the normal aging process, and they fail to seek treatment because they figure it is inevitable. Other patients may enter the American healthcare system with a goal of relieving their symptoms, and they expect medication to cure their illness immediately. Once their symptoms disappear, they stop taking their medication. Again, you have to understand where they are coming from.

Health and Illness

While providers often think of health and illness as matters of objective fact, the truth is that perceptions of health and illness, as well as beliefs and values about healthcare, are all influenced by culture. What is meant by health, how illness is defined, how the body is understood to function, what constitutes disability, and assumptions about how illness is caused are often culturally defined. Likewise, views about how illness can be cured and who does the curing are also influenced by cultural values and beliefs. If you have the opportunity to travel abroad in other countries, whether in a first-world country or a third-world country, it is interesting to ask some of these kinds of questions. It is quite amazing to find out how they perceive illness and who does the curing, and where they go for help. It is not always to the medical professional, the hospital or the physician.

Factors Influencing Illness

Again, numerous factors can influence a patient's experience of illness. Socioeconomic status and religious traditions can have an impact. Many people will go to a religious person for healing instead of a medical type of person; sometimes the religious and the medical are the same. Family relationships, beliefs about a supernatural world, fatalism, and understanding of the causation of illness all have an influence. Oftentimes people do not understand the true cause of the illness.

For example, some Native Americans, American Indians and Alaskan natives believe healing will result from sacred ceremonies that rely on having visions and using plants and objects that are symbolic of the individual, the illness, or the treatment. Some Asian cultures believe that illness is caused by interference from malevolent spirits. Some Hispanic cultures practice traditional medicine that includes folk remedies. There is a rich tradition of using herbal and home remedies in the African-American culture. We are seeing a lot more home remedies in traditional culture as well.

Understanding the Patient

The takeaway is that understanding the patient's interpretation of his illness is closely related to understanding alternative sources of care. To explain and to treat illnesses, many cultures use traditional or folk models of care - treatment that is deeply grounded in cultural practices. Many folks use complementary types of medicine or alternative medicine, and sometimes that is related to culture, or sometimes it is driven by poverty or lack of access to conventional healthcare.

Guidelines to Address Folk Beliefs

Regardless, you need to understand that so that you can, if possible, incorporate that into your treatment plan. You want to provide culturally and linguistically competent care, and you want to be able to integrate those traditional care approaches with the conventional, evidence-based medical approaches. You do that by becoming aware of behaviors and beliefs in their community. Assess the likelihood of the patient or the family acting on those beliefs during an episode or a specific illness. You hope to arrive at a way to negotiate successfully between the two belief systems.

I think if we just scoff at patients’ traditionally held beliefs regarding medicine or illness or curing, we are not doing ourselves any favors. We need to try to understand, to the best of our abilities. Every patient is going to be different. When you can incorporate a patient or family’s belief system, then compliance improves and satisfaction improves. Elicit patients’ understanding of illness and their experience, and bring that in. This encourages patients to become partners in their own care so they are not just being driven by the care that we are delivering, but they are active participants therein.

Patient-Centered Care

Providers often ask me, "How in the world am I going to incorporate that into my plan of care?" I wish I could give one answer to that. You need to work with the patient to figure that out, to uncover what those meanings and rituals are, and to marry them together with your traditional ones. I think that is the crux of patient-centered care, is it not? This is what we talk about so much in healthcare now. Patient-centered care is an essential component of cultural and linguistic competency. It is an approach that involves being aware of the role that cultural health beliefs and practices play in a person's health-seeking behavior, and being able to negotiate that as well. The IOM states that patient-centered care “establishes a partnership among practitioners, patients and their families (when appropriate) to ensure that decisions respect patients' wants, needs and preferences, and solicits patients' input on the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care.” It is a holistic approach. It really looks at culture, and the social influences on health and on health beliefs.

Principles of Patient-Centered Care

You probably know these principles. We obviously want to treat everybody with dignity. Patient-centered care is unbiased; we share unbiased information with our patients and their families. On the flip side, as we receive information from them, we do not react to it in a negative way, or show any sort of bias or prejudice. We strengthen the patient's sense of control by allowing them to drive their care. And we collaborate with our patients, with their families, and with the broader community in deciding how the healthcare organization looks and functions. I think that is important because any patient who comes to you with her cultural background is going to be part of a larger community, and oftentimes, you are treating that community as much as you are treating the patient. The more we can involve the community, the better off we are.

Communication Techniques

Munoz and Luckmann (2005) came up with some basic transcultural communication techniques, and there is a little more information about them in one of the handouts.

Let’s say you are meeting someone for the first time, and he is from a different culture than your own. Approach slowly, be respectful, and ask, "How would you like to be approached? How would you like me to call you?" Sit a comfortable distance away. Make sure it is a quiet setting. Allow for time to explain, to listen, etc. In other words, make it a setting where he can speak to you more than you speak to him. In that way, you can uncover what he needs from you.

Balancing Knowledge-Centered and Skill-Centered Approaches

Obviously, with everything we are talking about, we need to balance knowledge and skill.

Knowledge-Centered Approach

A knowledge-centered approach relies on specific information about cultural beliefs of various groups, and on demographic data that highlight group differences. Understanding a culture can really help. It is valuable in providing competent care, and it gives you a framework, if you will, about that culture.

Cultural knowledge can help you to establish rapport, create a trusting relationship, and prevent unintended consequences or offenses. If you know a bit about that culture, you can approach somebody in a certain way. Knowledgeable of the culture can help to reduce misunderstandings.

However, if you only rely on a knowledge-centered approach, you are missing the boat. You are not taking into account that individual patient, her background, her values, and her perceptions. She may not fully ascribe to what her society or culture believes; she may have different beliefs, and you need to uncover those. That is why it is so important to communicate with the individual patient and learn about her specific health-related cultural beliefs.

Beliefs about health and illness can be categorized in many different ways; for example, by cause of illness, religious beliefs, historical influences, or role of the family. It is important to understand that all cultures, including the majority culture, hold health-related beliefs; every culture does.

Many cultures believe that illnesses have supernatural causes. Some individuals from parts of Latin America, for example, believe that physical illness can be caused by the “evil eye.”

As for religious beliefs, prayer can be seen as the method of healing and may serve as a compliment or an alternative to medical care in many cultures. Even looking at the culture at large, how often do we hear, "I am going to add you to my prayer circle," or “I will say prayers for you"? The belief in the power of prayer is one that we see in numerous cultures. There are also beliefs about the will of God that may impact individuals’ or families’ decisions to seek healthcare. They may believe that they are in God's hands, and there is nothing they can do to prevent or manage a disease, so they may not seek out healthcare or follow through with recommendations.

Historical and current disadvantages are commonalities for many minority populations. These disadvantages include racial discrimination, denial of equal education opportunities, economic discrimination, and political disenfranchisement. Although some of those barriers have been reduced or eliminated, disparities and inequities in healthcare still exist. There are various contemporary factors, too, that contribute to medical mistrust; these include the shortage of racial and ethnic minority healthcare providers; the disproportionately high number of minority patients residing in medically underserved areas; and a reliance on traditional non-Western cultural medical practices.

There is also the role of the family. In some cultures, as we have already said, family members are expected to play an important role in treatment decisions, and in others, they rely on the village to help to make that decision. In yet other communities, independence and individual decision-making are highly valued.

Some cultural and religious groups, such as Orthodox Jews or Middle Eastern patients, prefer healthcare providers that are the same gender as the patient. Since many Native Americans and Alaskan natives are bi-cultural, healthcare providers may blend Western and traditional healing practices for successful treatment and prevention of health problems.

In the United States, about one-third of adults are using some form of complementary or alternative medicine (CAM), though many fewer patients actually discuss it with their healthcare providers. For whatever reason, in the United States, healthcare providers are not always on board with those alternative medicines, and patients are hesitant to tell them about it because it is not respected, or it is left behind in favor of other traditional approaches. Many people are using different types of multivitamins or over-the-counter herbal supplements or other things that they are not necessarily telling the healthcare provider or physician about. Again, improved understanding of how the health-related belief system differs and how these differences influence healthcare practices will certainly help you.

Skill-Centered Approach

The reality is that it is not feasible to know every cultural belief that your patient holds. Instead, you want to seek out the patient's understanding of illness and treatment. A skill-centered approach involves developing individual cultural competency to provide patient-centered care, and developing communication skills to understand your patient's experience. The two important paths to this are through self-awareness, which we already talked about, and reflection about cultural identity and beliefs through experiences with cross-cultural encounters.

Principles. The process of cultural competency includes making progress toward adopting these principles. You need to understand yourself in terms of culture and reflect on your beliefs, as I just said. You need to understand how race, ethnicity, gender, etc. plays into the perception of healthcare for your patients. Also, you need to understand the community that you serve and the different cultures within that community. Depending on where you work, you may serve a specific community, and maybe that makes it easier because you can just tailor it down to the individual. But in many places, we have multiple types of cultures coming together and we need to really understand all of them.

We need to examine family beliefs, and we must develop cultural humility. We are not always right, correct? We need to practice cultural etiquette - respecting others and respecting their opinions.

Remember, too, that this is a commitment to lifelong learning. It is not a specific achievement, as in, “I am now culturally competent.” Instead, it is moving toward cultural competency as a lifelong achievement.

We need to balance knowledge-based approaches (without stereotyping our patients) with skill-centered approaches, and that is going to help deliver better care. You need that balance between the two approaches because if you rely only on knowledge, you might stereotype, and if you just rely on the skill-set, you might not understand the culture at large. Be sensitive to the health beliefs of your patients and balance those two things.

Incomplete information. The reality is that we are always working with incomplete information in culturally rich situations. No matter what we do, no matter how detailed, how sensitive, how thorough, how inquisitive, you cannot ask all of the questions. You cannot always know all the questions to ask. You may not ask the right questions at the right time. Even if you could figure out the right questions, you do not have enough time. You cannot alter the fact that it is just not possible. You need to make decisions, make recommendations, treat and help heal.

When time is limited. Within those time constraints, there are some things that you can do. Remember that every interaction is an opportunity to assess and to treat. Even if you just have 15 minutes, a casual conversation can provide a lot of really good information. Informal conversation during the course of another activity may provide the most useful information because the individual is focused on doing an activity, not on giving you the right answer; therefore, they may open up a bit more.

Attend to observed behavior. This is really important. For example, where does the patient's spouse sit when you are doing your intervention? If he is sitting on the floor, then that should lead you to think, "I need to address this somehow in my treatment. I need to work on having this person get down to floor level for a conversation or something."

Ask questions, demonstrate techniques, and practice the skills more than once. Repeated discussion is going to provide richer description, and over time, patients and families are going to gain more confidence with you, and the answers that they give you should probably be more complete.

Watch for verbal cues to meaning. Pay attention to pauses, hesitations, word choice, repetition, etc. Any of those are going to give you useful information about behavior and beliefs that patients cannot articulate directly. Likewise, those cues will give indications of any misunderstandings that may have occurred. Note also the behavioral cues to meaning, such as shifts in body posture, eye position, increased motor activity, twitches and the like; these can all help you interpret meanings.

Finally, check your information. As we have established, it is impossible to know everything about every culture. Even if you could, you would still need to incorporate individual factors. So as you gather your information - as you make interpretations, ask for clarification, ask for confirmation - check with the individual to make sure that he is understanding.

Culturally and Linguistically Competent Organizations

Culturally and linguistically competent organizations. These are organizations that accept and respect differences among and within different groups. They continually assess their policies, and adapt their service models to make sure they are meeting the needs of different cultures. Within these organizations, they are hiring staff who are unbiased, and who represent the cultural communities that are being served. They have a commitment to policies that will enhance services to a diverse clientele. Every organization, regardless of size, has a role in ensuring the delivery of culturally competent care.

Again, culturally competent care is respectful. A culturally and linguistically competent healthcare organization should have diverse staff. They will have qualified interpreters and translators, if that is necessary for their patient population. Signs and written instructions will be provided in the patients’ language(s). The organization will offer training to providers to help them better understand the culture. It is a journey, and so we want to provide ongoing training as often as needed to make sure we serve the folks that have entrusted their care to us. This becomes that much more important when somebody comes to us from a culture that perhaps we are not familiar with.

What Can You Do?

What can you do to support your organization? You can educate yourself; that is why you are completing this course. By using cultural and linguistic competency practices when interacting with your patients and colleagues, you can encourage others to do the same. You can educate your colleagues about the characteristics of culturally competent organizations. As a group, you can review those national standards for culturally competent organizations, and figure out where your organization stands. You can also consider the cultural and the language needs of your patients when you recruit and hire new staff. If you have somebody available to you from that culture, then perhaps that is the person to hire.

You can convene a committee, a workgroup, or a task force to address cultural and linguistic competency issues. You can ensure that the mission statement commits to cultural competency. We already talked about finding out who we serve, and how the services may need to differ. A self-assessment can be conducted for the organization.

Obviously, you cannot single-handedly establish a culturally competent organization, but you can certainly support and influence endeavors in your organization by being culturally competent yourself. In addition, you can recognize when you and/or others in your organization were not culturally competent, were not sensitive, or perhaps did have some stereotypes or biases. Do not be hesitant to bring those up and discuss them within the appropriate forum.

Incorporating into Daily Practice

What do you do in daily practice? First, interview your patients. Sometimes we are focused on getting through that assessment as quickly and efficiently as we can and writing up that plan of care. We would do well to step back and take the time to do a thorough interview and really get to know our patients. The more you get to know the individual up front, either during the initial interview or soon after, the better able you will be to establish a plan of care that is meaningful and will work for her.

Use what you have learned to listen, to explain, to acknowledge, to recommend, and to negotiate health information and instructions. Be that cultural broker, if you can, for your patient, to help her understand the healthcare situation or environment that she is in, and then try to marry that with her background.

It is so important to elicit the patient's health experience. Again, use what you have learned to identify the patient's explanation of illness, his treatment, and his traditional treatment practices. That goes such a long way to helping with carryover of the skills that you are teaching.

Therapists as Advocates/Advocacy Skills

Patient advocacy is an important part of our work. Advocating for patients is not just done in the work environment; you can practice advocacy on a daily basis. You can guide your patients through the healthcare system, provide referrals, and encourage communication. Given our history as patient advocates, therapists are ideally positioned to champion for cultural competency. We can advocate for patient satisfaction, fewer medical errors, and better access to healthcare. We have the combination of skills to communicate effectively with patients and their families and other healthcare providers, with knowledge of the cultural beliefs and practices of our patients. We can work collaboratively to promote change. We are willing and able to serve as a change agent. And we have a commitment to diversity and provision of quality care to everyone.

So, within your own organizations, be the advocate. I can almost guarantee that everybody listening to this training today is thinking of a scenario you have encountered where you did not act in a culturally sensitive way. Let's learn from those experiences. Let's do a quality assurance performance improvement process to figure out what we could be doing better to help our patients. That is really what it is all about. It is not about us; it is about them. We want to be the cultural broker to help them to navigate the healthcare system.

Case Study

I want to finish up with a short case study that pulls it all together.

Context

Let me give you the context of this case study first. It is a person who has diabetes. The prevalence of diabetes in the United States has increased dramatically over the past few decades. According to the CDC in 2011, approximately 26 million Americans have diabetes, and that is over 8% of the current population. That was a dramatic increase of about 2.5 million cases over 2008.

How does this break out? Racial and ethnic minorities have higher rates of diabetes. The rate is 16.1% for American Indians, and 11.8% for Hispanics. The rates for Puerto Ricans - and this is important for the case study - are high both in Puerto Rico and on the mainland, with slightly higher rates on the mainland.

There are many theories about reasons for the differences in the incidence of diabetes between racial and ethnic minority groups, including lack of access to adequate and appropriate health information and treatment. This speaks to our ability to be cultural brokers and use health literacy skills to provide patients with information in a way that is understandable. There is also a lack of culturally sensitive interventions. Because so much of diabetes treatment centers on lifestyle choices, such as diet and activity, interventions need to fit into cultural values and preferences.

Hispanics constituted about 15.5% of the United States population in 2010, and that number is projected to be about 20.1% by 2030. Approximately 9% of this group are from Puerto Rico. There are four million individuals from Puerto Rico living in the United States. Puerto Ricans have a 66% lower high school completion rate and a higher poverty rate than the United States population as a whole, and also as compared to other Hispanic groups. Forty percent of Puerto Ricans speak primarily Spanish at home, and report that they do not speak English proficiently.

Background

Here is the background. Dr. Hathaway's office in Chicago received a call from a woman who wanted to make an appointment for Mrs. Sylvia Hernandez. The caller reported that Mrs. H. was having some difficulty with weight loss, dizziness, thirst, and lack of energy. The receptionist requested any previous records, and prior to the appointment, the following information was provided by a Dr. Yao in New York City.

Medical History

Mrs. H. has Type II diabetes, diagnosed 20 years ago. Since her initial condition was stabilized, she has not been on insulin. Her medications have been adjusted and she currently takes multiple medications twice per day. She was instructed to monitor her blood sugar each morning and was shown by the nurse how to do so. She has moderate hypertension and is taking two medications to manage that condition.

I am already thinking, “She has limited English proficiency and she was instructed to monitor her blood sugar every morning. The nurse showed her how to do that probably once, right? Was that carried over? Probably not.”

Social History

The medical records include the following social history. It is unclear who provided it. Mrs. H. is a 62-year-old Puerto Rican woman who moved to the United States at the age of 18. She had just married; her husband was also 18. He had family in New York, and that is why they moved there. He was an auto mechanic. She stayed home to raise three kids: a son, age 38 now, and two daughters, ages 36 and 35. She lived in New York until her husband died from kidney failure secondary to long-term hypertension. At that time, she moved to Chicago to live with her oldest daughter.

Mrs. H. left school at the age of 16. She and her husband lived in a Puerto Rican neighborhood in New York where Spanish was the main language, and as a result, her English proficiency is very limited. Once her children were grown, she worked occasionally as a housekeeper.

Office Visit

The doctor’s appointment was made by her daughter, with whom she lives. However, Mrs. H. comes to the office alone. She tells her doctor, "I feel tired all the time and I have no energy. I do not want to do anything, but I am supposed to fix supper for everyone. I am thirsty a lot, and I am getting too skinny. Sometimes I sweat too much. I feel really bad."

Occupational Therapy

The daughter accompanied Mrs. H. to the OT appointment. The daughter reports that her mom is a good cook. She enjoys hearty Puerto Rican food. She helps her daughter by cooking for the family a couple of times per week. She pitches in with light housekeeping. She used to watch her grandchildren while her daughter worked, but the children are adolescents now, and they have little time for her. She misses them and fills the time by watching Spanish-language soap operas. In the winters, she is housebound because of the weather. She spends most evenings watching television in her room so she will not interfere with her daughter's family.

She is a devout Catholic that goes to mass every Sunday unless the weather is bad. Recently, her church decided that they were going to close as a result of cuts imposed by the diocese. The church she is being directed to is a mile away, and that is either going to require a car or public transportation. She never learned to drive – she is dependent on others for transportation - but she does not want to ask her daughter to take her places.

Her daughter states as they leave the appointment, "She does not do any of this now. I think she has just gotten lazy. She does not get out of bed some days."

Physical Therapy

An interpreter was used during this appointment. Through the interpreter, Mrs. H. indicates that she never exercised, even when she lived in New York City. They resided in a fourth-floor walkup, and taking the stairs was her only exercise. In her current residence, there is an elevator. She is transported by a van to the senior center. Twice a week, there is an exercise program at the senior center; she participates because her friends do, but she hates it. Otherwise, she has no physical activity.

Nutrition

Mrs. H. prefers traditional Puerto Rican food, so when she cooks those two or three nights a week, she draws on those food items. Her daughter provides the meals the remaining days of the week, bringing in food from various fast food restaurants because they are so busy. Mrs. H. is about 30 pounds overweight. She says, "The doctor said something about sugar, but I do not worry about it. I just eat what I have always eaten because that is the best thing to do when you do not feel well." There is an example of that cultural attribution to food as it relates to health.

A participant has commented, "Not driving is pretty common for women her age in Puerto Rico; my mom does not drive either." Thank you for sharing that, and I will tell you, that is true. In many cultures, women do not drive. My grandmother did not drive, my great-aunt did not drive, and a lot of family members do not. We have to certainly consider that that is a typical thing in many cultures.

Questions to Ponder

I am not going to give you the answers to these questions, but I want you to think about them. For your own discipline, what other information would you need to know in order to determine why she is having difficulty? What background information might you need to know about beliefs held by individuals from Puerto Rico, and/or her family? As noted in her social history, her English is limited, so what strategies do you need to use to make sure that you get an accurate history from her, and that your findings are accurate? How certain are you that the information from her previous physician, or even her daughter, is accurate, and what steps can you take to make sure they are accurate?

What do you see as your unique role for your discipline in working with this particular client? What other disciplines might be helpful in the situation, and whom might you work with? In this case, she is well and able, but we do not know if she has a communication disorder at all, or if she is having any sort of swallowing issues. You need to take that into consideration; how does her background fit into that, and particularly her love of Puerto Rican food?

How might your own ethnicity and language impact your assessment and the care that you deliver to this person? How would it be different if she were from a different ethnic, racial or socioeconomic background? For example, what if she was from the working class, or what if she was Vietnamese, or Muslim? Thinking about how that situation might differ.

Follow-up

This is a real scenario. Mrs. H. has a chronic condition that is going to require continual monitoring. Here is what they ended up doing for this particular patient: the dietitian gave her suggestions that were very consistent with her dietary preferences, and taught her how to prepare those foods so that they were better for her disease. Mrs. H. worked with the OT and the PT to find things that were enjoyable for her so that she had more activity in her day. They worked on her health literacy so that she could better communicate with various healthcare professionals. Part of that was teaching her how to test for her insulin, administer insulin, etc.

Three months after the initial appointments, her lab values were fine, and she had more energy. She still has not found any activities that she really likes, but OT and PT are going to continue to follow up. All of these disciplines looked at her culture, her background, and where she came from. All of those things are critically important because they influence her health and her perception of illness and how she is presenting today.

Questions and Answers

Q: Do you have a grasp on how well this is covered in allied health graduate programs these days? Are our speech/OT/PT students receiving much in the way of cultural competency training, or does that tend to happen on the job?

A: My experience has been that very, very little is happening at the graduate school level, unfortunately. I think much of what they are getting is when they are out in the field, doing their clinical fellowship or on-site types of training or starting their first job. If the site where they are going is culturally competent or working toward it, they are getting plenty of training. If the site is not, then I do not think that they are.

Somebody in our audience is commenting that she had an entire semester class on the topic. I will tell you that I teach at a couple of different universities, and this is not being covered to a large degree. I think the good news is that if you look at what Medicare and other types of insurance companies are doing, there is a big push for education about this out in the community, so I think we are going to see more and more of it. Another participant is chiming in, "We had excellent training in a master's program, very specific to different groups." Again, I think that might be regional or program-specific.

One of our attendees makes an excellent point: "I had a course on it in grad school, but it is hard to know how to apply that until you are actually out in the workplace, and you see how what you learned might be applied in the real-world context."

This whole concept goes hand-in-hand with health literacy; there is a push for education related to health literacy. I think it, again, depends on where you went to school, what your training was, and how recently you went. I can only speak for myself; even in my doctoral program, it is not something we covered. I went to school in a very culturally rich community, and it was somewhat intuitive to me, but I do not think it was something that we were taught, per se.

Citation

Weissberg, K. (2019). Delivering Culturally Competent Care: Strategies for Clinicians. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20095. Retrieved from www.speechpathology.com