Learning Outcomes

After this course, learners will be able to:

- Define and discuss how to apply the principles of backward design.

- Define and discuss how to apply the levels and types of cognitive knowledge.

- Describe how to design formative and summative assessments appropriate for selected course objectives.

Introduction

This course design overview was developed to help audiologists with little or no background in course planning. We use the term “course” throughout, but these concepts can be applied to university courses, presentations, guest lectures, workshops, and the like. This course will cover the process of planning your teaching. We recognize that not all audiology instructors have had formal course design instruction before starting their teaching careers. Our backgrounds are in clinical audiology and teaching academically in clinical audiology programs. In addition, Dr. Billingsly is a PhD candidate in Instructional Technology, and Dr. Skinner has taken formal courses in course design and educational technology. Our goal is to give you a framework for developing your teaching plan. We encourage you to reach out to your university’s teaching support center or other course design experts for further resources and support.

Getting Started

This tutorial uses backward design as the framework for designing your course. In backward design - which could be thought of as matching Stephen Covey’s “Begin with the End in Mind” - our teaching practices are goal-oriented, fully aligned, and intentional. Wiggins & McTighe’s classic approach from Understanding by Design (2005) outlines three stages of developing a course:

- Identify the Desired Result

- Determine the Acceptable Evidence of Learning

- Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction

This approach is called “backward” design because it contrasts with the “traditional” approach, where the instructor first decides what content to cover, then delivers the content, then gives an exam. It is tempting to begin course planning with a list of topics; with backward design, the initial step is to determine what we want students to be able to do because they took our course. In backward design, the instructor can be assured that their course elements (e.g., content, practice activities, and assessment) will be tied together. Further, backward design is ideal for ensuring that competency-based standards (such as the ones used by accrediting bodies) can be adequately addressed. We have included an editable planning worksheet as an attachment to this course. The worksheet was designed for you to create a teaching plan using the three steps of backward design. The first pages of the worksheet are filled in with an example, followed by a blank worksheet for your use.

Step One: Identify the Desired Result

The initial step includes identifying the course goals, considering the level and type of knowledge students will acquire, and writing learning objectives.

Identify the Course Goals

The course goals are the “big ideas” - the most important knowledge and skills we want our students to gain. As you identify the big ideas in your course, consider your learners. Are they beginners or at a more intermediate level? What other knowledge or previous experiences do they bring to the class? What do you want them to be able to do or explain after finishing the course?

- Question 1: What are the “big ideas” in your course?

Consider the Levels and Types of Knowledge

Levels of Knowledge

Learning is generally categorized into three domains: cognitive (knowledge), psychomotor (skills), and affective (attitude) (Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, & Krathwohl, 1956). Even though audiology students learn all three, we focus here on the cognitive, or knowledge, domain. To identify what we expect students to learn, we need to consider what level and what type of knowledge we want our students to gain. The taxonomy of types and levels provides a structure to align learning objectives, instructional strategy, assessments, and course materials. This framework can help us to better understand what it is that we are planning to teach. It can also help us break down our expert knowledge and make it accessible to learners.

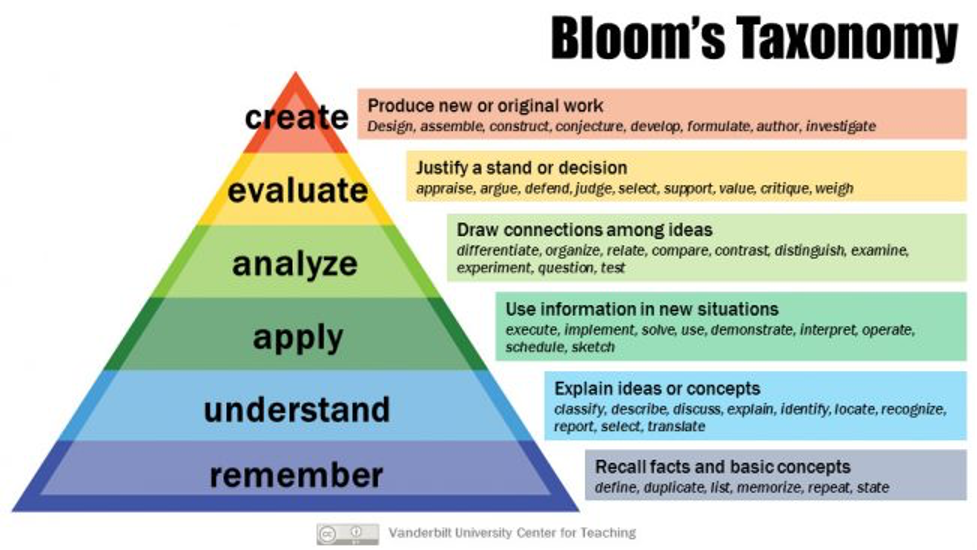

Bloom’s taxonomy details levels of learning, progressing through degrees of complexity. This section provides a brief overview; each section in this tutorial will have you consider the taxonomy when designing your course. Figure 1 illustrates and provides examples of the learning complexity at each level. An example of what our students learn at each level is outlined here, using acoustic stapedial reflex testing as an illustration.

- Remember: Define the terms ipsilateral and contralateral

- Understand: Draw a schematic of the ipsilateral and contralateral acoustic reflex pathways

- Apply: Predict the reflex pattern based on location of pathology in the auditory system

- Analyze: Given case history, pure tone air and bone thresholds, speech testing, tympanograms, and acoustic reflexes, identify the site of lesion shown in the test results

- Evaluate: Given an audiogram for a given site of lesion, determine whether acoustic reflex thresholds given are consistent or inconsistent with the diagnosis

- Create: Create a case for an imaginary patient with a given disorder, to include case history, audiogram, and immittance data

Figure 1. Bloom’s taxonomy levels with examples of the learning complexity at each level. Image credit: Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

For example, in developing this tutorial, we knew we were working with experienced professionals and adult learners, but also that some of our material may be new to those learners. Thus, we knew that our targeted cognitive processes would be a mixture of more simple entry points, leading toward higher levels.

- Question 2: What cognitive levels does your course target?

Types of Knowledge

The types of knowledge range from concrete to abstract. An example of what students learn within each is outlined here, using acoustic stapedial reflex testing again as an illustration.

- Factual knowledge (facts, terms, details): to perform reflexes, students must know terminology including ipsilateral, contralateral, reflex, stimulus; the anatomical and physiological components of the reflex arc; and the decibel.

- Conceptual knowledge (classifications, theories, models): to perform reflexes, students must know concepts such as ascending and descending pathways, the appropriate methods of obtaining thresholds, potential abnormalities or artifacts that might be present, the patterns of reflex results and their implications, and the relationship of auditory thresholds to reflex thresholds.

- Procedural knowledge (doing. investigating): to perform reflexes, students must know how to assemble the probe unit, obtain a seal and recognize a leak, manually control the equipment to pressurize and present a stimulus and decide when a full vs. an abbreviated reflex battery is indicated

- Metacognitive knowledge (reflective awareness): to perform reflexes, students must know how to structure their learning approaches, self-monitor, self-assess and self-correct in the other domains, and incorporate feedback from patients and preceptors/instructors.

For example, in developing this tutorial, we planned to address factual and conceptual knowledge of course design.

- Question 3: What types of knowledge does your course target?

Write the Learning Objectives

Ideally, your course will be designed so that each element leads to the same place: the attainment of the “big ideas” or goals for your course. After identifying the goals of your course, the next step is to write learning objectives, both course objectives and module/lecture objectives. Objectives are formatted similarly to what those in business might call “SMART goals” (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based). They are narrow, measurable elements of student performance. Your course objectives will be the larger or more challenging end-points, and the module or individual course session objectives will be smaller and more specific. Good objectives include four major components: audience, behavior, condition, and degree.

Each Objective Should Include:

Audience: who will be doing the behavior?

Behavior: what should the learner be able to do?

Condition: under what conditions do you want the learner to be able to do it?

Degree: how well must the behavior be done, what is the degree of mastery expected?

Measurable Action Words

The verbs used in objectives are actions that can be taken. Students should be able to use your learning objectives to assess their progress through the course, so we should avoid “fuzzy” words (like “understand” or “know”) that are hard for a student to measure. For example, consider the difference between these two objectives:

Upon successful completion of this course, a student will be able to:

- “Understand acoustic reflexes” vs.

- “Select, perform, and interpret ipsilateral and contralateral acoustic reflexes”

To create your learning objectives:

- Consider the levels of knowledge your students will be expected to achieve (lower-order to higher-order thinking skills). These are represented in the rows of Table 1 below.

- Consider the types of knowledge students will be expected to achieve (concrete to abstract). These are represented in the columns of Table 1.

- Determine an appropriate action verb to describe what students should be able to do. Table 1 provides an example verb for each type/level combination.

- Specify the conditions under which they should be able to do this.

- Specify the degree of mastery expected to indicate success.

Cognitive Process Dimension (Bloom’s) | Knowledge Dimension | |||

Factual | Conceptual | Procedural | Metacognitive | |

Remember | List components of … | Recognize signs of … | Recall how to … | Identify strategies for … |

Understand | Summarize features of … | Classify x by y | Clarify instructions to … | Predict one’s response to … |

Apply | Respond to typical questions on … | Provide advice to novices in doing … | Carry out … | Use techniques to match one’s strengths in … |

Analyze | Select the most complete list of … | Differentiate x vs. y | Integrate activity x and rule y | Deconstruct one’s biases about … |

Evaluate | Check for consistency in sources of … | Determine relevance of results to … | Judge efficiency of technique in … | Reflect on one’s learning progress in … |

Create | Generate a log of activities in … | Assemble a test battery for … | Design efficient workflow to … | Create a learning portfolio |

Table 1. Adapted with permission from Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, Iowa State University. Levels of knowledge are represented in the rows. Types of knowledge are represented in the columns.

There are many lists of learning level verbs available, though most sort by level of cognitive process (Bloom’s taxonomy), and do not differentiate by type of knowledge. You may find it useful to try an online learning objective generator to help you format your course objectives.

Using the previous example of students learning acoustic stapedial reflex testing, we might decide that for first-semester students in their first assessment course, we are expecting an “Apply” level of cognitive process, and factual through procedural knowledge. Thus, our end-level objective for it could be:

Upon successful completion of this course, students will be able to carry out ipsilateral and contralateral acoustic reflex threshold measures on a compliant adult with minimal support.

On the other hand, if we had second-year students demonstrating previously-gained skills in a clinical setting, we might be expecting an “Evaluate” level of cognitive process at factual through metacognitive knowledge. Thus, our end-level combined objective for it could be:

Upon successful completion of this clinical experience, students will be able to accurately reflect on their clinical use of immittance evaluations, including how they consistently determined the relevance of clinical findings to diagnostic outcomes, and judge the efficiency with which they performed the testing on a diverse patient base in an outpatient clinic, with minimal support.

If you are teaching a course in an audiology program, you may be given course learning objectives that were developed by the department’s curriculum committee. We suggest you use these as guidelines to identify what type and level of knowledge is being taught in the course and ask for clarification if needed. In this case, you would only need to write learning objectives for individual course sessions or modules.

For example, in developing this tutorial, one of our objectives was, “Upon completion of this tutorial with a quiz score of 80% or better, participants will be able to independently write effective course objectives that align with the student, setting, and appropriate cognitive domains.”

- Question 4: What are your primary course objectives, using objective structure and measurable language?

Step Two: Determine Acceptable Evidence of Learning

Assessment of learning outcomes generally takes a two-tiered approach encompassing summative and formative assessment.

Summative Assessments

A summative assessment is used to see if the learning objective was met. These are typically conducted at the end of a unit or after a certain number of weeks of instruction, and at the end of the course. We recognize that there may be certain course formats or departmental policies that dictate the type of assessment that you can use. If not otherwise restricted, the format that you choose should measure the complexity of learning targeted in your learning objective.

In a written exam, if the learning objectives are at the remembering or understanding level for factual knowledge, multiple choice, fill-in-the-blank, matching, and ordering questions can assess this level of learning. Short answer or essay-type questions are a good choice for the “understand” and “apply” levels, particularly for procedural or metacognitive knowledge types.

For more complex levels of learning, presentations, projects, and portfolios allow the instructor to assess the student’s learning. A presentation, where students typically present to their class and answer questions, gives the instructor an opportunity to see how students analyze a topic. A project, which typically requires students to create something relevant to the course topic over a relatively long period of time, requires that students be at the evaluate or create knowledge level.

- Question 5: What will be your summative assessments, matching them to your course objectives?

Formative Assessments

A formative assessment is meant to identify current understanding and progress toward the learning objective. These are given regularly throughout the course, perhaps even multiple times within a course period. These assessments are generally not graded or are presented as “low stakes” (worth a small percentage of the final grade) activities. Formative assessments can help the instructor identify areas where further clarification or more time spent on a concept is needed. There are many formative assessment tools that are easy to learn and use. The examples below are not meant to be an exhaustive list of either the formative assessment types or the way in which they may be used but may give you ideas for how you might better understand students’ learning as they progress through your course, and perhaps inspire an internet search for more ideas.

Online polls and surveys: Online polling tools can be used to give students practice with concepts and to identify where students may be struggling. Questions can be targeted to match the level of learning. Responses can be reviewed as soon as they are submitted, giving the instructor the opportunity to spend more time where needed.

Entry or exit ticket: Students are given a prompt and submit a quick response either at the beginning or end of the class.

“Muddiest point”: Students are asked to indicate what concept is the most difficult for them after the lesson. These can be submitted and reviewed by the instructor at the next session or can be reviewed on the spot.

Formative assessments may enhance student metacognition by helping them to identify their progress toward a learning goal. This is helpful for students who may be overestimating their understanding of a concept. Formative assessments can also increase student engagement during class time or provide structured reviews during their work time outside of class. To get started using formative assessments, we recommend deciding what you want to learn about students’ progress. Do you want a general feel for how well they understand a concept, do you want to make sure they understand certain concepts before going further or moving on, or do you want to see how prepared students are for your summative assessment? Then decide if you want to do the activity before, during, or at the end of the course period. Select an activity that matches what you are using the assessment for and is easy for you to implement.

- Question 6: What formative assessments will you use, matching them to your objectives and your summative assessment?

Step Three: Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction

Planning the learning experiences involves considering your instructional strategy and planning the course content.

Instructional Strategy

The instructional strategy refers to the overall framework within which your students interact with your course content. Instructional strategies range from predominantly teacher-directed, where the focus in the classroom is primarily on the instructor to predominantly student-centered, where students have more choice in their learning and learning is customized to the student. The Table 2 below illustrates a selection of commonly used instructional strategies in audiology education.

Instructional Strategy Type | Name | Example |

Teacher-Centered | Lecture | Instructor presents content in lecture format |

Teacher-Centered | Worked Examples | Students follow along to a step-by-step example |

Teacher-Centered | Interactive Lecture | Instructor pauses one or more times during the lecture to give students time to interact with the course material |

Student-Centered | Case-Based Learning | Students learn by reading about and working through cases |

Student-Centered | Problem-Based Learning | Students learn material through solving large, open-ended problems |

Table 2. Selection of commonly used instructional strategies in audiology education.

Within any given course, more than one instructional strategy may be chosen. Teacher-directed instructional strategies are suitable for the foundational levels of Bloom’s taxonomy, while student-centered strategies are more suitable for the higher levels. This is not to imply that one approach is superior; the instructional strategy should match the complexity of learning that is targeted in the particular course.

- Question 7: Which instructional strategies will best prepare your students for your assessments?

Course Content

Now that you have identified your learning objectives, selected your summative and formative assessments, and considered your instructional strategy, it’s time to develop the content of your course. Course content can be delivered in a variety of ways and we encourage creativity and variety in this area. This section will review some important considerations when developing (or editing existing) content.

Content Delivery Forms

As most of us are aware, it is common to use slides created with PowerPoint, Google Slides, or similar. This is a great tool to deliver content, keeping in mind some basic design principles.

- Choose a template that does not detract from the information on the slide. Keep text to a minimum and make use of empty space.

- Spread the information across two or more slides if you find that one slide is becoming too crowded with text.

- Use graphs and tables, either created by you or copied and credited from another source, when information can be easily conveyed in this way.

- When applicable, use art or other images to convey information.

- Make sure that your slides are designed for accessibility:

- Select font type and color contrast that are accessible to students with low vision.

- Use alt text or image descriptions for any images, tables, and graphs.

- Make sure any embedded videos are subtitled/captioned.

- Reach out to your university’s accessibility coordinator or teaching and learning center for guidance for each of these.

Other forms of content delivery include online videos, Audiology Online courses, podcasts, and written materials such as textbooks and journal articles. Each of these formats provides a perspective that can supplement and support what the instructor develops and presents. Make sure when selecting content that it is accessible. When your time for planning and availability of resources allows, it is beneficial to provide students with options. For example, you may create an assignment where students can either watch a particular video or read a particular article. The way in which content is delivered is going to depend on the instructional strategy. We also recommend incorporating collaborative assignments, both inside and outside of class, into your content delivery plan.

- Question 8: What forms of content delivery will you use within your instructional strategies, matching them to your assessments in support of the learning objectives?

Avoiding Expert Blind Spots

Equally important to the format of the content delivery, if not more so, is delivering content that is designed for the current understanding and professional developmental level of the student. There can be a large mismatch between the novice level of our students and our expert level as instructors. This mismatch is sometimes referred to as an “expert blind spot” (Nathan & Petrosino, 2003). After someone develops expertise, they can forget how difficult certain topics were to learn. They assume that students are keeping up with what they are saying because the material they present is easy for them. However, the instructor is quite possibly leaving out certain important foundational concepts or not giving students enough time to process new (to them) concepts.

One manifestation of the expert blind spot in clinical instruction is when an instructor describes how to carry out a clinical procedure. The literature tells us that when experts, even award-winning teachers, teach a procedure to students, they leave out up to 70% of crucial steps (Sullivan et al., 2014.) If you’ve ever participated in or observed the “exact instructions challenge” for making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, you have seen expert blind spots in action. In this challenge, someone who knows how to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich writes out step-by-step instructions. Another person takes these instructions and follows them word for word. The instruction-writer tends to leave out important details such as opening the jar of peanut butter or specifying which side of the bread to use. This is because they figured the sandwich maker already knew these important details or they forgot to include them because the process is so automatic.

We offer the following suggestions for addressing your expert blind spots.

- First, acknowledge that these exist and they may in fact be difficult to identify.

- When planning course materials, stop and think about what your students actually know coming into your course and what they need to know to meet the learning objectives. As experts, it is sometimes more interesting to talk about advanced concepts, but if you are talking above your students’ understanding, you won’t be able to teach them very much.

- Allow your students plenty of time to process and practice new information.

- If you expect students to have base-level knowledge before your class begins, a pre-test can identify gaps and remind students of areas where they need to review.

- If you notice students consistently struggle in a certain area, it’s possible that you’ve gone too quickly or left out important information. Go back to the basics and identify everything that students need to understand a concept.

- It can be helpful to ask a more advanced student for help, as they are somewhere in between novice and expert and can help you better understand the challenges of the novice learner.

- Consider Bloom’s taxonomy, ensuring you aren’t asking students to apply or analyze when they don’t yet remember or understand.

- If you have the time, you might try to learn something new and remind yourself how difficult it is.

- Question 9: How will you address your expert blind spots?

Summary

Backward course design may initially seem counter-intuitive. However, we can apply that concept to anything we do in audiology. Let’s use a hearing aid fitting as an example. In a hearing aid fitting, our objective is to reach audibility goals and patient benefit and satisfaction. Our assessments are probe microphone verification of target match and carefully selected validation measures. With these tools at the ready, we can design the content (programming) of the fitting to meet patient needs. So, too, in the classroom, with the objectives and assessments in mind, we can accurately prescribe the necessary content to support student progress toward meeting the learning objectives. We hope that you find this course immediately applicable to your course design efforts. In our combined 15+ years of teaching, we’ve seen that courses that are designed intentionally, using educational theory, result in better student outcomes and a more enjoyable - and less stressful - teaching experience.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the guidance we both have received from our respective universities’ faculty development programs, A.T. Still University Teaching and Learning Center, and Northern Illinois University’s Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning.

References

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved November 16, 2023 from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay.

Covey, S. R. (2020). The 7 habits of highly effective people. Simon & Schuster.

Heer, R. (2012). A model of learning objectives—based on A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching, Iowa State University.

Nathan, M. J., & Petrosino, A. (2003). Expert blind spot among preservice teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 40(4), 905-928.

Sullivan, M. E., Yates, K. A., Inaba, K., Lam, L., & Clark, R. E. (2014). The use of cognitive task analysis to reveal the instructional limitations of experts in the teaching of procedural skills. Academic Medicine, 89(5), 811-816.

Citation

Skinner, K., & Billingsly, D. (2024). A course design overview for audiology instruction. AudiologyOnline, Article 28840. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com