Editor's note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live webinar. Download supplemental course materials.

Valeri LeBeau: Today’s learning event, Core Strategies for Supporting Children with Deafness and Autism Spectrum Disorders: Part 2, concludes this special series sponsored by Advanced Bionics. As professionals, we are challenged to provide the best interventions for children who have this dual diagnosis. Today’s webinar will take a deeper look at how to plan for a child with hearing loss and autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Dr. Stacey Jones Bock: We are going to take a few minutes to talk about evidence-based practices. When you are supporting children with deafness and autism, it is incredibly important that you refer to the adjacent field. For instance, we need to look at both deaf strategies as well as strategies in the autism spectrum realm. This is why we are starting with evidence-based practices.

The terminology “evidence-based practice” comes from the field of medicine in the 1990’s. It means using research to inform your practice. We know that medical trials are steeped in research. For accountability measures, we as educators are also somewhat steeped in research. Once medicine coined that term, it spread quickly to our discipline.

In education, the call for teaching practices to be supported by scientific research extends back to No Child Left Behind (NCLB), which was signed into law in 2002, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA) of 2004. Even though this legislation provided motivation for the use of evidence-based practices in the greater education community, the autism community demanded effective, scientifically based practices even prior to NCLB and IDEA mandates. Their true demand came from the rise in the prevalence of ASD. It also came from the challenging behaviors that can be associated with the disorder, and because the field of autism has also attracted a high number of what we consider controversial treatments and intervention strategies that have little to no empirical support with “supposed” great results.

Defining Evidence-Based Practice

Definitions of evidence-based practice have been debated in the field for many years, especially with the increase in the numbers of cases of autism, which I just discussed. At that time, there was a great deal of pressure for schools and districts to provide services that were proven to be effective. If you think about an increase in a population of children, which at that time was an increase in students with ASD, also think about your district having an increased need for highly trained professionals. Then think about in what methods they should be trained. Therein lies a problem.

At that time, parents and advocates for children with ASD wished for programs for children. For instance, in the 1990’s, the program of choice was the Lovaas Discrete Trial Training Model. At that time, it was one of the only programs that had data to support a child’s learning.

In 2001, the National Academy of Sciences created a community to identify evidence-based practices for children with autism. They looked at comprehensive program models, such as the Lovaas program. They stated that scientific research consisted of four things: empirical investigation, linking findings to a theory of practice, providing a coherent chain of reasoning, and replicating and generalizing across studies. They tried to define how we know that this practice is going to work for multiple children with autism. They were the ones to set guidelines at that time.

Recent Activity

Over the years, several efforts have been made to critically review the research and look further at identifying evidence-based practices for children on the spectrum. Each study contributed to building a theoretical framework for evaluating and identifying evidence-based practices for children with ASD. Most recently, two centers published their findings. These were the National Autism Center’s National Standards Report and the National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders. Let’s take a look at some of the information that came from those reports.

The National Standards Project (NSP) was conducted to establish a set of standards for effective, research-validated educational and behavioral interventions for children on the spectrum. The goal of the NSP was to investigate the research behind all interventions available for children and adolescents with ASD. This committee developed a scientific merit rating scale to objectively evaluate the research that was out there on this population. They used different dimensions and looked at research design, measurement of independent variables, the participants themselves, eligibility, and then the treatments and interventions. There were components that looked at professional judgment, values and preferences for families.

Here is a list of some established treatments. You will notice that two of those are in bold type. The first one is Antecedent Package and the second one is Behavioral Package.

- Antecedent Package

- Behavioral Package

- Comprehensive Behavioral Treatment for Young Children

- Joint Attention Intervention

- Modeling

- Naturalistic Teaching Strategies

- Peer Training Package

- Pivotal Response Treatment

- Schedules

- Self-management

- Story-based Intervention Package

When we look at these, it is important that we point out that many of the interventions that we are looking at as being effective for children with a dual diagnosis of deafness and autism are based out of the antecedent package and behavioral package.

The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders also published some data. We looked at both of those centers and identified the common interventions that were found to be evidence-based practices by both centers. We felt comfortable with that list and in recommending and researching in those areas. The commonalities of those findings resulted in 14 interventions, as follows:

- Antecedent-Based Instruction

- Differential Reinforcement

- Discrete Trial Instruction

- Visual Supports

- Functional Communication Training

- Video Modeling

- Naturalistic Intervention

- Task Analysis

- Parent-Implemented Interventions

- Peer-Mediated Instruction

- Social Narratives

- Prompting

- Reinforcement

- Self-Management

Those interventions in bold are the ones that we felt, across both centers, could easily be implemented with the dual diagnosis population. We are going to break down these interventions and talk with you about the implementation of some of those.

What Can Evidence-Based Interventions Do?

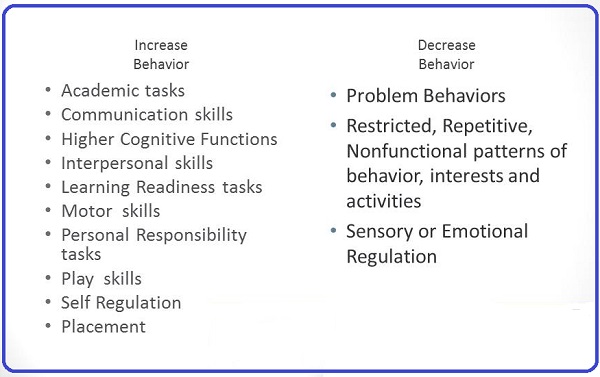

Figure 1 shows what these evidence-based interventions can do to increase or decrease behavior.

Figure 1. What evidence-based interventions can do to increase or decrease behaviors.

The skill areas you can increase behavior include performance in academic tasks, communication skills, interpersonal skills, learner readiness, play skills, and self-regulation. You can decrease problem behaviors, restrictive and repetitive nonfunctional patterns of behaviors interests and activities, the impact of sensory stimulation on a child and emotional regulation issues. All of these things have been identified in the literature to increase some behaviors and decrease others.

Dr. Christy Borders: Stacey has a long history of research and expertise in the area of autism, and my background is deafness. We combine our expertise into what happens with children that have both of these disorders simultaneously.

One of the things that Stacey went over briefly, which I would like to show you as well, is what evidence-based practice is in the field of autism. I assume most of the participants of this presentation are in the field of deafness. There is 50 years of research that has established the evidence-based practices in autism. Clearly, through this research we have evidence indicating that 14 practices will be effective for children with autism. In deaf education, our pedagogy and approach to learning has been around a long time, but we do not have the same body of research for evidence-based practices in our field, partly because we are a low-incidence population.

However, I think what makes our approach to deaf children and deaf education unique is the fact that we primarily use modeling, shaping, and prompting in our instruction. Across the spectrum of deafness, we utilize things like bilingual/bicultural strategy or auditory/oral strategy. We focus on using specific strategies to increase literacy skills, language skill, speech, listening, and reading. That is what comprises deaf education. We are good at modeling a practice that we expect a child to do, shaping their responses, prompting them to further extend on their response, and then using basic reinforcement. This is historically what deaf education has been for years, whether or not there is research documenting that specific sequence.

Where do Stacey and I recommend that teachers begin for children with this converging disability? The first place that we recommend starting for any child who is engaging too much or too little in a behavior is functional behavior assessment.

Functional Behavior Assessment

Our first recommendation is conducting a functional behavioral assessment (FBA). This means using this strategy of assessment for understanding the function or purpose of a student’s behavior. It is trying to figure out what the payoff is for a student to engage in a particular behavior. There is a reason why a student continues to engage in that behavior. Conducting an FBA helps you to identify the payoff and then select more appropriate means to get the same payoff. In other words, you can put an intervention in place that serves the same function to the student. They are communicating their desire with a behavior. This is where we would recommend always starting with a student that has a dual ASD/hearing disorder diagnosis.

It is important to know that some behaviors may serve more than one function for your students. For example, a child could be hitting for multiple reasons. They could be doing it to gain attention, to escape a situation, or to control a situation. It is also true that different behaviors may serve the same function. A student may throw a pencil, throw a tantrum, talk out in class, or refuse something all to gain attention. That relationship can go either way, and identifying what a student gets out of engaging in a specific behavior is critical when you are trying to develop meaningful consequences and interventions to replace negative behaviors.

Dr. Bock: An FBA is almost like peeling back the layers of an onion until you get down to the most usable component on the inside. If a behavior happens, it happens for a reason. If there was not a reason, the child would not have that behavior. Instead of looking at behavior on the surface for what it looks like, such as throwing an object or throwing themselves on the ground with a tantrum, refusing, or crawling under a desk, look beyond that superficial view of the behavior. You have to ask yourself why he or she is doing that.

Steps of the FBA

Dr. Borders: The number-one thing that we talk about when doing an FBA is that when you boil down a behavior to its function, you are able to remove emotion from the situation. It is not that the child is doing it because he is mad or just trying to get under your skin. Identifying the function removes an emotional response to behavior and find the functional intent behind the behavior. It sets a productive and positive approach to how to deal with behaviors that are difficult and impeding instruction. Let’s quickly discuss the steps for an FBA.

The first step is giving very clear description of the inappropriate behavior and then determining the antecedents. Antecedents are the things that happen before the behavior. You have to determine what things happen right before that behavior, so that we may change some of those things.

Through the process, you will identify the function of that behavior. Then you have to come up positive alternatives to that behavior. “How can I teach Stacy how to gain my attention appropriately? She does not have to throw a pencil at me.” That is a critical step to identifying these interventions.

You also want to look at what you or others have tried before, and determine if those methods worked or not. Lastly, always go through this process with data collection and data analysis.

Dr. Bock: Why do we look at data collection? I know people dislike writing down the numbers and tallying them. It is cumbersome when you are trying to teach, but the importance is there. If I say that the child tantrummed twice during the day, that does not sound so bad. However, if I collected the right data, I would go beyond that and collect how long the tantrum lasted. The child may have only tantrummed twice, but each tantrum lasted 50 minutes. In total, the child tantrummed 100 minutes through the day. That defines that behavior.

Let’s take it one step further. If, by collecting data and putting an intervention in place, I were able to reduce that by three minutes a day, where would I be at the end of a month? You could get rid of 80% of that behavior in a month with the correct intervention. It is important to collect that information so you know where you are standing.

In summary, our number one recommendation is to do an FBA. If you would like to learn more on FBA, please refer to Part 1 of this series.

Functional Communication

The second strategy is functional communication training (FCT). It is a basic, biological need for us to be able to communicate our wants and needs. It is also a human right. That is why we are starting at this level. We do not want a child engaging in behavior because they have no functional means to communicate what they need or want.

FCT is an intervention designed to decrease unwanted behaviors by replacing them with meaningful or functional communication. In other words, rather than having a student tantrum or use their behavior to have their needs addressed, the learner is taught to communicate their needs in a more socially accepting way. Are you concerned about a child’s needs if they are on the floor kicking and screaming? You are more concerned about the active behavior that is going on. It is probably not as effective for them, either.

In a social environment, they are not going to have their needs met until we provide them with functional communication. We would much rather have a student sign, use words or an alternative communication system, use gestures, or even point. With FCT, the emphasis of the communication is on functionality instead of the form. How functional is that communication for the child? We will take a child pointing at something they want. We are going to take a child gesturing, because we are looking at the functionality of that communication, not the form of the communication.

FCT relies on an accurate understanding of the function behind the problem behavior. Is it attention seeking? Is it trying to access a preferred item? Is it trying to escape or avoid something in the home or classroom? We have to know that in order to replace that behavior.

Implementation

We do not implement FCT until after we have completed the FBA and have identified the function of the unwanted behavior. For example, a child screams loudly multiple times a day. An FBA is performed and the results show that the student is yelling to escape the environment. The teacher then implements a take-a-break card, and the student is taught to hand the card to an adult in the environment, or sign “break” or say “break.” That alternative communication is honored immediately.

The steps of implementation are very similar to most interventions. We will talk about replacing an unwanted behavior with a more socially acceptable behavior. The focus of the new, acceptable behavior is always communication.

First, perform the FBA, identify the behavior and form a hypothesis. For example, Mindy bites students in her preschool classroom in a play area. After completing an FBA, the hypothesis of the biting behavior is to obtain a toy that another student is playing with at the time.

The second step is to match the function of the behavior to the message of the alternative communication that will be taught. For example, because Mindy is biting to gain access to a toy or another child’s possession, the functional communication training replacement could be having Mindy either hand or share a picture of the toy to the student or sign or gesture. In order for this to be successful, the other children would need to be informed in the environment as well, and Mindy would need to share her icon or provide her gesture in close proximity to the other child in the room. The new desired communication behavior has to be performed just as easily as or easier than the unwanted behavior.

During the training portion, you may have to physically guide the child over to the other preschooler and physically help the child show the picture or sign or gesture. They will not get their needs met if they are standing in a corner performing this behavior.

Step three is the prompt the use of the replacement communication and reinforcement of desired behavior with the desired outcome. You, as the teacher, would need to stay in the play area, and when Mindy approached another student, you would prompt her to use the “share” icon or prompt her to sign or use a gesture. If she did, you would positively reinforce her. Likewise, she would be reinforced because she would receive that tangible item that she wanted.

It is a step-by-step teaching process. If she tried to bite the other student but was unsuccessful in her attempt in that engagement, then you would prompt the use of the “share” icon. There are two things that could happen when she approaches. You catch her and redirect her to the functional communication behavior you want her to perform, and you try to do that before she bites the other student.

Another important step of FCT is collecting the behavioral data. When teaching the FCT, I like to sabotage an environment. If I know that Mindy loves the Magic School Bus toy, then I will make sure that I place that toy with a peer in that environment. I know that she will automatically go there. I have set up the environment for that teaching situation.

Think about ways in which you can get communication going. If you are trying to teach a child who gets frustrated during meal time, and the frustration stems from not knowing how to request utensils or a drink, then place that child’s favorite edible item in front of you during snack time in order to sabotage the environment and set up the communication process. You can then begin that FCT.

Antecedent-Based Interventions: Reinforcement, Visual Strategies, & Choice-Making

Dr. Borders: We want to discuss three other interventions you can try. You start with FBA, and move on to FCT. After that, we move into the realm of antecedent-based interventions (ABI). ABIs include our other three suggested interventions to start: reinforcement, the use of visual strategies, and the use of choice.

ABIs are designed to modify the environment before the targeted negative behavior occurs. Again, if you know Mindy is on her way over to bite another child, then you are going to intervene and focus on teaching things like on-task behaviors. This is why the FBA is always our number one recommendation. You will observe in the setting where there problem behaviors occur. Many times for our students, there are multiple settings, and you need to determine if there are things specific to an environment that may trigger a behavior. Then you will determine the changes that you can make to that environment.

ABI Strategies

Dr. Bock: The first antecedent-based strategy is learner preference or reinforcement. Next is altering the environment for success. If you have child that has difficulty during transitions, altering the environment would be something like using transition warnings. This is something I believe we all do in the classroom.

Implementing pre-activity interventions is another strategy. This is getting the student ready for an activity that they will be doing. Using choice-making is another strategy. I cannot tell you how important choice-making is and how it becomes more important as the child ages.

We can alter how instruction is delivered to the child. What is required of that child in the environment is probably one of the most difficult things for us, as teachers, to change. However, it can be very important to use in order to lower incidences of behavior. Lastly, we can enrich the educational environment.

Learner Preferences

With learner preferences, you are incorporating a student’s special interests into a task or activity. If you know that this child loves Legos, then you can use Legos as manipulatives in a match activity. You can use Legos to teach color words. You can use Legos to build items that represent things in the environment to engage that child and then learn from those.

Discover a child’s strong likes. Then you figure out how to imbed that in teaching opportunities. Every child has likes, but when you are working with a child on the spectrum, they have what we consider special interests. Sometimes they may be obsessive special interests. They work very well to keep the child engaged.

Dr. Borders: It is not uncommon for us to hear, “All he ever wants to talk about is Legos. I am not going to talk about that because I am just reinforcing his focus on Legos all day long. Legos do not make the world go round.” However, I think that one of the things we find, as teachers, is if we can learn to use those obsessive or pervasive special interests, we can increase student engagement in the classroom. Something as simple as putting a picture of a Lego on a worksheet makes it reinforcing.

If you are having trouble getting a child to sit and work at the table, why not use something that they absolutely love to get them to engage in a task they would not do otherwise. We spend a lot of time helping teachers be okay with the use of special interests. It might change your approach, but we tend to find that works very well with students on the spectrum. We can also use those special interests as reinforcers.

Identify Reinforcers

Dr. Bock: So we have performed our FBA, we are looking at functional communication and are modifying our environment. Another key component is identifying what is reinforcing for that child. What do you go to work for daily? Why do you go to work? What do you get out of it? You might get some satisfaction that you are doing a job well. You are good at what you do. Hopefully, you receive a paycheck for going to work, which is an automatic reinforcement. Maybe you like the socialization that you get at work. You are gaining something out of going to work that is reinforcing for you.

With children, you need to perform some type of reinforcer preference assessment. This will be different for everyone. You do have to think outside of the box when identifying reinforcers. What is reinforcing for me is not going to be reinforcing for you or every child.

We cannot go with what we think is reinforcing for a child. We have to probe. Some methods for determining reinforcers are to ask a student if they are able to tell you what is reinforcing to them. You can have the student list those reinforcers in order of preference. The number one reinforcer is going to be the one that you use for the behavior that needs to be changed the most. This is why a ranking order is important.

You can also observe a student. We are often engaged with children who have low communication and high levels of behavior. If you watch them go into any room, observe what they go to. Maybe it is a DVD, a specific toy, or a specific food. You know that what they are going to is reinforcing for them. You can use those items for reinforcement.

You can also do a reinforcer sampling or preference assessment. In this case, place items in front of a child and see what they reach for first. You are structuring that environment. With the population of children that I have served over the past several years, I have had to do reinforcer sampling in order to ascertain what is reinforcing for them.

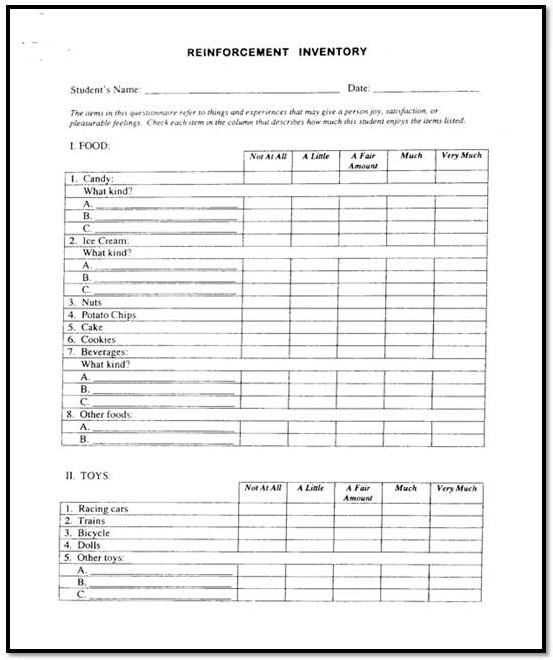

Figure 2 is a reinforcement inventory sheet. You can find different formats online. It looks at food, toys, and other things. If there are behaviors that need to be changed and food is a reinforcer, then you are going to use those things. It is not always going to be there, as you will need to fade that over time. However, in order to get the child to perform the new behavior, you may have to use things like food.

Figure 2. Example of a reinforcement inventory.

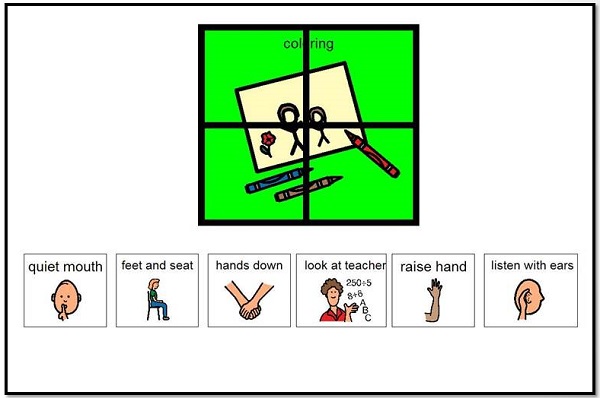

Another example is shown in Figure 3 for a child who likes to color. Notice that there are four different puzzle pieces there. The rules are on the sheet with quiet mouth, feet and seat, hands down, look at the teacher, raise your hand, and listen with ears. Those are some of the behaviors that we look at that child having in place, and as they perform those, they will earn a piece of that coloring puzzle. Once they have earned all four pieces, then they get to color.

Figure 3. Reinforcement activity for coloring.

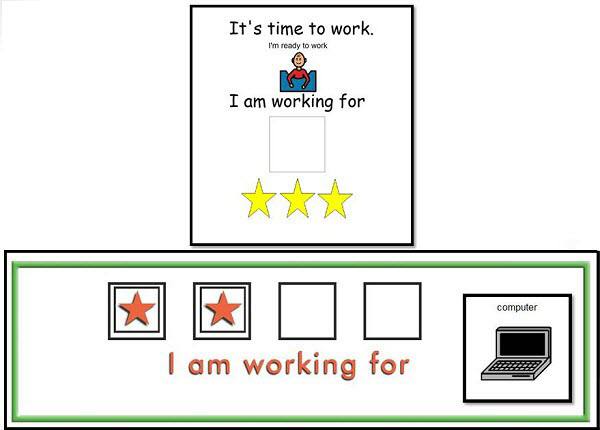

Figure 4 shows another example. The top says “It’s time to work, I’m ready to work and I’m working for _____.” You would place a picture of that child’s desired item in the blank space.

Figure 4. Open-ended reinforcement activity.

When providing reinforcement, you always want to move along the reinforcer hierarchy. We have primary reinforcers and secondary reinforcers. Primary reinforcers are food, edibles, and things that are sensory in nature. Sensory items could be a multitude of things such as soft touch, sitting in a basket swing, et cetera. Secondary reinforcers are those tangible items such as toys that the child likes. They are also privileges or activities. Maybe the child loves to go outside and swing or walk around the track at school.

Social is the highest level of reinforcement. You begin at primary and then you move on to secondary. You want to pair reinforceres. For example, you would pair a social reinforcement at that same time as you are providing a child with an edible. You are always trying to pair primary reinforcers with secondary reinforcers.

Altering the Environment

Dr. Borders: Altering the environment is an ABI. There are countless ways in which you could alter your environment to help decrease behavior in your setting.

The first way is by adding visuals. Visuals allow you to change the visual structure in the classroom by defining areas. Some classrooms are very organized, and visually you can see what is going to happen in which areas of the room. This helps students who may not know where to go or cannot navigate the classroom easily. With the use of visuals, they stay put, like they have been given a direction.

Directions given orally or through sign disappear, but when you use a visual, it stays there, and the student can continue to reference it over and over again. We highly recommend looking at the classroom or clinic environment to see if it is visually difficult to navigate. You can change seating or add space between students if they have difficulty keeping their hands to themselves or biting. Visual timers are also very helpful. It lets a student know how long they have to work before they can get to their reinforcer.

Pre-Activity Interventions

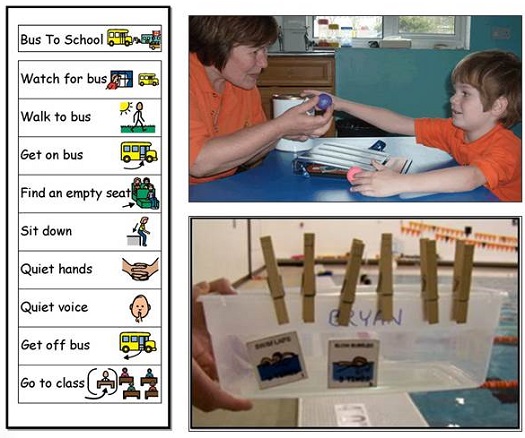

Dr. Bock: Pre-activity interventions include pre-teaching materials, providing transition warnings and mini-schedules or task organizers. Figure 5 shows examples of these. A mini schedule for the child lets them visually see what is occurring throughout the day and the behaviors that they are supposed to be performing during those times. There are many ways to give transition warnings. The task organizer at the bottom of Figure 5 was for a swimming lesson. The laundry clips were used for whenever they went down and did a lap and back, they would pull one off and put it in their box. Using those types of pre-activity interventions and visual strategies allows the child to become more independent in that process.

Figure 5. Examples of pre-activity interventions including mini schedules and task organizers.

One quick note about using visual or mini schedules is that teachers should make a good attempt at creating a schedule or visual representation of what they want the student to try, with as many detailed steps as possible. When you see a student break down, then you know that there need to be more steps added.

We talked a little bit about instructional delivery, but I want to point out that we should provide fewer verbals and to use more gestures, modeling, and prompting. We expect gestures from a child for our functional communications, but we as teachers oftentimes flood a child, with communication impairment, with too much communication. We need to pare that down.

Let me give you an example of one of our students, Nick. He loves drawing and does an amazing job. He likes to go on YouTube and watch videos. His edible is Lay’s Potato Chips. We have identified those reinforcers. Step two in the process is his identifying his unwanted behavior. He was on the computer non-stop and he would not help with any chores. Therefore, he was not learning any functional skills, and he was 16 at the time. We needed to find an ABI that matched the function.

After we did an FBA, we found out that he did not understand the request. He was frustrated that his mom kept asking what he should do. We gave him a task organizer that he could check off, and we also gave him a choice board. After he completed his tasks, then he was allowed to choose some type of reinforcer that he liked.

The last step was our collection of data. When a task was completed, he checked the sheet, and by doing that we were able to collect data on how many times he took out the trash, how many times he took care of the recycling, et cetera. This example illustrates a child that did not know what to do, but we put the supports in place, he could independently do it, was reinforcing himself, and we were able to make quantifiable progress.

Dr. Borders: Again, visual supports can be any visual tool that you present to support that student throughout the day. It could be something like schedules, labeling the environment, clear visual boundaries, organization systems, choice boards, and scripts. Giving choice gives them some ownership in their learning, and those can include pictures, words, objects, or even pictures of the sign can be used.

Visuals must be taught. You cannot just put them into the environment and expect a student to know how to use them. You have to teach it. It could happen after one trial, but it may take weeks for that to become meaningful for a student in context.

Next Steps

Now that we have completed the most important steps, let us leave you with the next three recommendations: Task analysis, Shaping, Differential reinforcement. We recommend if you are comfortable with the steps we have outlined today that you look into task analysis, shaping of behavior and furthering your reinforcements into differential reinforcement of behavior as a way to shape behaviors.

Questions and Answers

You mentioned the different types of visual aids in a classroom such as objects, line drawings, and photographs. How important is it for teams to work together, whether it is with an occupational therapist, a vision specialist, speech language pathologist, or parents, to determine the child’s ability to understand and to choose the appropriate visual aid? For instance, if they are unable to process line drawings, we would move towards photographs?

You have to look at the level of attraction for the child. If they cannot use line drawings, I would move back to real pictures prior to moving to real objects. If you have a child who is not responding to a real picture of the item, then you are going to have to move back to real objects.

We typically have to move back to objects when the child is very young or whenever there is an associated intellectual impairment. Those are two things you need to think of, but you also need to be able to work the other direction. We do not often pair a word with an object, but we like to place a word on pictures on everything so that the child begins to associate that script or word with it.

It is important that you pay attention. If you do not have a child responding, then you need to look at what you are doing and the level of abstraction. You hit an important point as well. The speech language pathologist, audiologist, the teacher, the parent, and everyone else involved needs to be using the same level of abstraction and the same level of supports. Once you do find the level of abstraction that is appropriate for the child, everyone has to be on the same page and move together into increasing to less abstract. You must consider level of abstraction as a team.

How many years of research are there in ASD?

We are looking probably at 75 years of research, specifically though at the intervention research that is out there. The field has gone back 50 years and analyzed that information. Our field, even though ASD has always been there, is not as rich and does not have as much history. I think because of those severe behaviors and the impact on the child’s ability to learn, socialize and communicate, there has been a greater rush to gather more scientific information.

The evidence-based practices that we shared at the beginning were taken from 922 empirical research articles that addressed and showed evidence of those practices. In the field of deaf education, there were only 20 over the last 40 years that met the scientific merit requirement for evidence-based practices. The difference in the amount of empirical research conducted between deaf and hard-of-hearing and ASD is very different based on the number of the people and the ability to get a control group. That is one of the reasons that we looked so heavily to interventions established in the field of ASD.

What would you recommend for a family with a child who has hearing loss and ASD who has chosen a spoken language approach, yet has not seen adequate progress in listening and spoken language skills?

I would recommend adding pictures to instruction to aid in bridging that gap between where they are with their spoken language and their level of abstraction. Part of the reason we always recommend the use of pictures or icons is because that signal does not go away.

If the child has trouble processing or attending, those directions can go away, but giving them a picture that they can exchange or add to communication, they can continue to reference that item because it is more salient. I would highly recommend adding something to the listening and spoken language signal that will not go away.

I have had parents say that they want their child to talk, so they do not want to put in a different type of augmentative or alternative communication for their child. The research shows that if the child is going to talk, having that augmentative or alternative form of communication, in fact, facilitates speech. Putting in the alternate form will be much more valuable. I am not saying to get rid of the words in his environment, but you should put an alternate form in place.

The other piece we can look at with a spoken language approach is to make sure they are working very closely with their audiologist so whatever technology they are using on their ears is programmed adequately and that they are making the most gain from their hearing aid or cochlear implant. The child needs to have the best access to the auditory sound to continue to develop listening and spoken language, in conjunction with a multifaceted approach.

Cite this Content as:

Bock, S.J., & Borders, C. (2015, February). Core strategies for supporting children with deafness and autism spectrum disorders: part 2. AudiologyOnline, Article 13190. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.