Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live webinar. Download supplemental course materials.

Valeri LeBeau: I will be your host today for this class, Planning Interventions for Children with Deafness and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Today’s webinar is the first in a two-part series that will help you understand where to start. I would like to welcome our experts on deafness with autism, Dr. Christy Borders and Dr. Stacy Jones Bock.

Functional Behavior Assessment

Dr. Christy Borders: The purpose of our presentation today is to provide an overview of the functional behavior assessment (FBA) process. We understand that children with strong behavioral needs can be frustrating at times. When you are supporting a child with deafness and an autism spectrum disorder (ASD), the level of frustration for both the teacher and the student multiplies. Why? Because the impact of ASD on a student who is deaf or hard of hearing is incredibly complex, and the strategies for supporting these students are typically novel for teachers, parents, and related service providers, sometimes going beyond our own expertise.

Dr. Stacy Bock: I wanted to take a minute to tell you how we arrived at this topic. Christy and I got together about five years ago and we began a conversation about deafness plus an additional disability, most specifically, autism. During our conversation, we realized that we had both supported a student with a dual diagnosis.

I was called in to consult with a teacher of the hearing impaired on severe behavior, which included aggression, refusal of the student to wear his cochlear implants, and his use of some self-stimulatory behavior. I gave my basic interventions with which they needed to start, but we had a very difficult time with the student in that environment. He was transferred to a communication- and behavior-based classroom in a public school setting. He began flourishing in that environment, and his negative behaviors subsided. His communication was a combination of pictures and sign, and that increased. His self-stimulatory behavior was almost nonexistent. He transitioned fairly independently. He did so well that the school transferred him back to the self-contained program for students that were deaf and hard of hearing.

Unfortunately, all of his previous behaviors were back in full force about a week after he was back. That is when my colleague, Dr. Borders, was called in to evaluate him. After her consultation, we both realized we recommended the exact same interventions for this child. As behaviorists, my area being autism and her area being deaf and hearing-of-hearing, it did not surprise us that our recommendations were the same. It also did not surprise us that we were both frustrated because we saw a child with so much potential go back and forth through an educational system. The trajectory of his education was not something that was climbing. We felt that he could have been much further along if he would have had consistent, appropriate education at that time.

Dr. Borders: Have you ever thought that your student was just being defiant? “He threw his cochlear implant across the room, for no reason. Why does he do the things he does? How can I make it stop? If he just had language, then his behavior would disappear.” If you have said any of these things, you should consider performing an FBA to determine the function of behavior. It is important that we take a moment and remember that behavior equals communication. The student is not acting in ways to be defiant or spite you. Instead, a student will use their behavior to communicate because it works. We need to find out the function of these inappropriate behaviors.

Functional assessment is a process that allows you to understand the function or purpose of the student’s behavior. It allows you to look beyond the behavior to uncover the communicative message.

What is the Function of a Behavior?

What is meant by the function? The function is the payoff that the individual receives by engaging in the behavior. All behavior occurs for a reason. Without a reason, there would be no behavior. I try to remember back to when my children were young and did not have any verbal communication; they communicated with their behavior. Sometimes they pulled me to what they wanted. Sometimes they climbed on tables and chairs to reach what they wanted. When I could not understand what they wanted, they would cry, bite, scream, throw things, and sometimes melt down. Does that behavior sound familiar?

Dr. Bock: Through this process, we need to see what payoff the child is getting by engaging in the behavior. Then we can identify and teach a socially appropriate way for the individual to communicate. We do not want to aim to extinguish behaviors. That is very important. If you walk away with two messages today, one would be that all behavior equals communication and the second would be not to work to extinguish behaviors. Unfortunately, if you do not replace a behavior that is serving a function, it oftentimes is replaced by even worse behavior.

History of Functional Behavior Assessment

To understand why FBA is important, I think it is necessary to talk about behavior support and behavior change, and how we arrived at this process across the years. Although FBA as a concept is as old as behavioral psychology, the current trend toward widespread implementation in schools began in the 1990s. FBA was originally used clinically in the 1960s and 1970s to try to understand why individuals engaged in self-injurious behaviors. This was the age of behavioral psychoanalysis, which had an emphasis on getting rid of inappropriate behavior by trying to understand where the individual was in the process of psychodevelopment. How could we move that individual to the next stage? FBA was an emerging concept, but not the primary behavioral psychology philosophy of the time.

In the 1970s and 1980s, FBA was still clinically present, but behavioral modification was the guiding philosophy. Behavioral modification had an emphasis on eliminating the inappropriate behavior, sometimes by way of negative approaches that may have been punishing to the individual, such as isolated time out or physical restraint. I remember as a teacher going through something called Mandt training. During that time in the 1980s, we were taught the four-man carry so we could carry a child to another location. Those were so intrusive at the time, and I remember after using some of these types of interventions in the classroom that no one won. The child felt terrible; I felt terrible. I knew it was not something right to do. What we did learn that was important was that those negative behavioral approaches did not have a long-term impact on behavior change. We also learned that if we did not replace the inappropriate behavior, the individual would exacerbate the inappropriate behavior that he originally had or begin to exhibit totally different behavior.

In the 1990s, we had a resurgence of FBA. As I said, we learned that those negative approaches did not work. We then began to take a look at the FBA for students that had behavioral issues, which is now required as a part of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) as of 2004. Because it was a part of the law, it was added as a part of the child’s individualized education plan (IEP). If the child engaged in behavior which impacted his or her ability to learn, then we were required by law to perform a FBA and write goals and objectives, which included a behavior support plan.

Terminology

Dr. Borders: Before we begin walking through the process of what we do to complete an FBA, we think it is important that we go over some basic ABA terminology. The terms that we are using are important to understand and often misused.

Reinforcement. Reinforcement is an important concept that everyone understands. It is an item, activity or event that follows a behavior and leads to an increase in the chances that that behavior will occur again. When you are completing an FBA, it is important to determine what is reinforcing for the student you are supporting. Sometimes a specific reinforcer may not be available or you may not have many options to use with that student. It is important that you identify what is reinforcing for that student and use it immediately and consistently.

Dr. Bock: I also want you to think outside of the box. Here is an example. I worked with a child who had autism with severe tendencies. He loved hair. When I was working with him to teach a functional communication system, he would like to play with my hair. He would touch it and run his hands through it. I did not let that bother me at all, because I thought, “He is engaged.”

Then I learned that hair was very reinforcing for him. I would make him work for 10 minutes, and then I would bend my head over and let him fluff my hair. I had a freshman honor student with me at the time who said, “Dr. Bock, have you ever thought about going to the mall and getting him a fake hair piece?” I went out that day and bought a fake hair piece for $10; that was the reinforcer that I gave the child. It was brilliant. Think outside of the box. It will not always going to be something to eat. It will not always be a sticker, a gold star, et cetera. It may be something sensory or something that would not be reinforcing to anyone else.

Dr. Borders: It is important that you have many options from which to choose, and know that they may even be unavailable to you. When I worked with a group of 14-year-olds with autism and deafness, many of my students’ primary reinforcer was swimming. I will never have a swimming pool in my classroom. This is why you need to have many options.

Dr. Bock: Another thing to understand is that if a challenging behavior is occurring, it is being reinforced. A student may be reinforced by something that is perceived positive by many. However, a student may be reinforced by something that is seen as negative by the general population, too. If it continues to occur in your classroom, you know it is being reinforced by something.

Punishment. Dr. Borders: Another term we need to understand is punishment. Punishment is only something that reduces the chance that a behavior will occur again in the future. As we know from our history lesson earlier, approaches that use punishment and aversive techniques merely try to extinguish a behavior and are not effective over time.

Another consequence of using punishers is that the application itself may invoke aggression or more severe behavior from the student. For example, if a student with deafness and an ASD runs out of the classroom and the teacher decides to place the child in a Rifton chair with a belt and a table connected, which prohibits him from moving, the teacher may be surprised when the child begins in self-injurious behavior, such as head banging or biting his arm or hand. We should try to never use punishment as an option when supporting children with complex needs.

Antecedent. Dr. Bock: What is an antecedent? Antecedents are the events that precede the behavior. They can include personal and environmental factors. It is important to keep a record of when certain behaviors occur throughout the day, the settings the child is in, people that the child is around, and activities and situations that occur or are present before the child exhibits the target behavior. When we gather this information, we can help identify patterns of the behavior, which helps us to determine what the child is getting out of engaging in the inappropriate behavior.

Think of antecedent as the event that sets the behavior in motion. There are two ways an antecedent can work: slow triggers and fast triggers. They can occur with each other, or they can occur alone.

The term slow trigger, or setting event, is used to describe the events that change the value of consequences in the student’s life. The occurrence of a setting event can explain why a request to complete a task results in a struggle and inappropriate behavior one day, but not the next. For instance, a student may find an academic test more aversive and will be more likely to engage in problem behavior to escape from this type of activity if he is ill or does not feel well. However, when he is feeling better and no longer sick, that same student will complete the same academic task and be reinforced by the teacher for completing the assignment. Those setting events can be physical, social, or biological. Setting events can precede or occur at the same time as the student engages in the challenging behavior.

Another example may be a lack of sleep the night before. During the first activity at school, the teacher might be surprised to see the student rip up his assignment and throw it on the floor. A concurrent setting event may include the presence of illness or pain. A student who is experiencing all these physical discomforts may strike an area that hurts, throw themselves on the floor, or rip up their papers.

Knowing what setting event is occurring is helpful and provides the team with a number of different intervention options. That is why communication between home and school is incredibly important. Mom or Dad might have insight into the child’s schedule or personal issues. Perhaps the child did not sleep. It is important that that information comes back to school so the teacher knows it.

Fast triggers are those antecedents that occur immediately before a student engages in an inappropriate behavior.

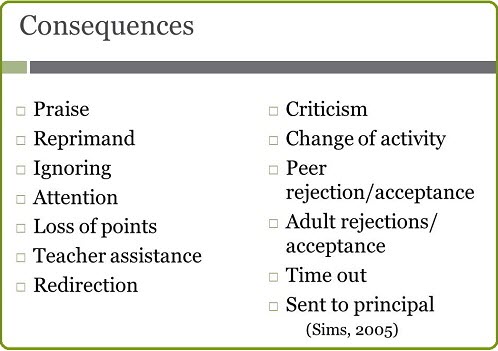

Consequences. Dr. Borders: In the FBA, we also look at consequences. Consequences are the events that happen after the behavior. Consequences are the contingency that maintains the behavior. They may be reinforcing, and as we know, this increases the likelihood that the behavior will occur again. Consequences may be punishing, which means it decreases the chance the behavior will happen again. Reinforcers and punishers are individualized. What is reinforcing to one child may be punishing to another.

Dr. Bock: A list of common consequences is listed in Figure 1. Let’s consider the consequence of praise. When praise is the consequence for the behavior, you will continually exhibit that behavior or behave in the same way to receive that reinforcer. The same goes for a child or a student you are supporting. If the consequence you are providing is reinforcing, the behavior may either be maintained at its current level, or it may increase and you will see the behavior more frequently. If the consequence is punishing to the child, then the behavior may not occur as frequently, but remember it will creep back up in some way. Children and adults are quick to learn that if they do one thing, they get either reinforcing or punishing consequences.

Figure 1. Common behavioral consequences.

Functions of Behavior

Dr. Borders: The FAB is the assessment of the functions of behavior. Children engage in challenging behaviors because it works for them. Generally, we talk about four categories of functions of behavior that have been empirically validated. An easy way to understand the functions of behavior is with the acronym SEAT, which stands for Sensory, Escape, Attention, Tangible.

One function of behavior is to meet a sensory need; that action feels good through one of the senses. How many of you are hair twirlers, gum chewers or pen tappers? You may not even know that you are exhibiting these behaviors, but as you do, you regulate your internal state. Individuals with deafness or hearing impairment and ASD often lack the ability to regulate or filter sensory information. Their nervous system seems to be over- or under-reactive.

Some behaviors that are performed for sensory input can include rocking, spinning, putting objects in the mouth, and hand flapping. When a child engages in these behaviors because they want to get away from something unpleasant, they may try to escape or avoid a particular sensory input. For instance, a student that throws their amplification across the room may be overwhelmed by the auditory input in their environment. While that may be one reason to throw a hearing aid, it could be serving any number of functions.

Dr. Bock: I also want to add power and control to the list of functions of behavior, although it is not a scientifically validated component. Many of our children are completely guided by adults in their everyday environment. They have very limited choice in where they want to go, what they want to do, and so on. Sometimes they go home and experience the same environment. Sometimes we may see a child act out just to gain some control over his or her environment and decisions they make.

Behaviors and functions can be reciprocal. A child could be hitting to serve multiple functions. They could be hitting to gain attention, to escape a situation, or for control. It is also true that different behaviors may serve the same function. A student may throw a pencil, tantrum, talk out, or refuse something all for attention. Gather as much information as you can about when, where, and why a behavior occurs to understand why the negative behavior occurs. We have to identify the correct function in order to develop a behavior support plan with meaningful consequences.

Replacement Behaviors

When thinking about an alternative replacement behavior you want to teach, it has to be easier and more effective for the student, and it has to serve the same function. If a child hits to gain attention, then we have to provide that child with another way to gain attention. Maybe it is touching someone lightly on the arm, and we may have to hand-over-hand show that behavior and teach the child how to do it.

Dr. Borders: Do children with a dual diagnosis of deafness/hard-of-hearing and ASD communicate differently? How would you communicate your wants and needs if you had low language levels? Imagine your teacher offers you Cheez-It crackers for the mid-morning snack, but the smell of Cheez-Its turns your stomach. In fact, after they sit on your desk, you need to run across the room to get that smell out of your nose. However, you love Goldfish crackers. How do you tell your teacher that you want Goldfish crackers but not Cheez-It crackers? Do you throw the Cheez-Its across the room? Do you scream whenever the Cheez-Its are set in front of you? Would you rip open every cabinet door in the classroom to try and find the Goldfish, or would you grab you teacher’s arm and pull her to the snack cabinet?

With low communication levels, it is natural to use your behavior to indicate wants. But what if you were 16 years old and needed to communicate this message? Now you are bigger than your teacher, and if you grab her hand to pull her to the snack cabinet, does that look more like aggression than the communication of, “I don’t want Cheez-Its, and I would rather have Goldfish?”

Define the Inappropriate Behavior

Dr. Bock: The first thing we are going to do is identify the inappropriate target behavior. In your assessment, clearly and concisely describe the behavior. The test to collect baseline data is the Stranger test. This means that a behavior has to be described in a way that any stranger could read my description and then be able to see that behavior and say either yes the behavior occurred, or no the behavior did not occur.

Why is this important? When you are performing an FBA, you will need to obtain information from other people in your environment. If you are in that environment with multiple people, you all have to be talking about the same thing. By targeting a specific behavior, everyone will be able to recognize and agree when it is occurring and when it is not occurring. We have to be able to see it to measure it, and it has to be clearly understood by all.

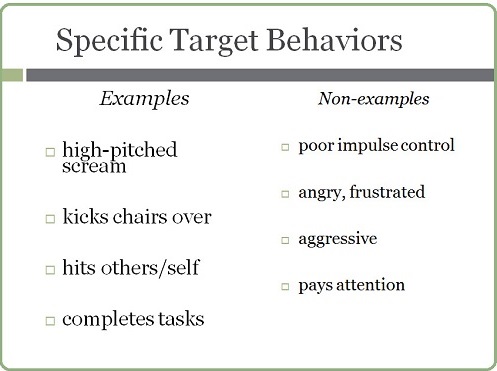

Figure 2 lists compares examples of specific behaviors and non-examples of behaviors. Target behaviors that are not operational or are poorly defined are prime reasons why FBA information can be invalid or incomplete. For example, if I see the child is angry or frustrated, what do you see? I would guess that if I asked five people what angry or frustrated looked like, each individual would come up with a different description. Why? Because behavior is subjective.

Figure 2. Comparison of specific behaviors and non-specific behaviors.

For example, some people cannot stand to have a child spit on them, but another person might be able to wipe that spit off and move on. Another person might hate to be pinched or kicked and another person might just rub the pinch or kick and move on. By specifically defining that behavior, we are making the behavior more objective. When behavior is objective, we are more likely to obtain information that we can use to support that individual. Objective definitions help us determine the function of the behavior so we can go on to develop support-centered interventions.

Dr. Borders: Our operational definition should be clear, observable, and measurable. We also need to think about what needs to be in that definition and what we need to collect. How long does it occur from start to finish? Does it occur more frequently around certain people? In what rooms or environments does it occur most often? Does it pass the Stranger test?

This information must be collected in data; not just subjective measurements. We need to collect information on the antecedents, which are those things that occur prior to the behavior, and also the consequences.

Data Collection

Baseline

Dr. Bock: Data collection plays an essential role when we are supporting behavior and developing a plan. To begin, it is important to establish a baseline measure of the important dimensions of the behavior such as frequency, rate, duration, latency, topography, force and locus. This baseline provides us with a clear measurable description of the behavior.

A baseline should consist of at least three data points, depending upon the behavior you are recording. Baseline data serves a descriptive function by telling us the student’s current performance level. In other words, it provides us with a foundation of where the behavior is.

It also provides us with a predictive function. By observing a trend in the behavior or the patterns of the data, we can see what is occurring before there is any intervention in place.

When choosing what aspects of behavior to capture, ask yourself which dimension, if changed, would result in the greatest benefit to the child you are supporting. For instance, if you are interested in a child’s tantrumming behavior, is the duration of the tantrum the most important dimension or is the intensity the most important? If the goal is to decrease the amount of time the child engages in tantrumming, then you would choose to collect duration information on the behavior.

Observation

Dr. Borders: You have already developed a clear definition of the targeted behavior. Now you will gather additional information about the variables that are maintaining behaviors using different methods. Those could include interviewing, a review of student records, or direct observation.

We highly recommend direct observation because it provides the most accurate representation of the student’s behavior. It involves directly observing a student’s behavior in their natural environment and then analyzing the antecedents or the environmental events that immediately precede that behavior and the consequences. If we look at things that happen right before and right after that behavior, then we can start to predict when the behavior will occur and why it is occurring.

Dr. Bock: Let me give you another example. You will be collecting on one of the dimensions (frequency, rate, duration, latency, topography, force and locus), depending on the behavior. Think about this. If I said the child had two tantrums at school today, you may not think that is very bad. We can get through two tantrums. But if I said the child trantrummed for over 90 minutes two times that day, that description gives you a better idea of what that behavior looks like. You have to pick up on the correct dimension.

Graph the Behavior

The next thing we want you to do is graph that behavior. The power of graphically displaying data cannot be overstated. Teachers make tally marks frequently documenting occurrences of behaviors. This is only one step into data collection. They need to take the next step and look at it visually. Presenting that data in a visual manner clearly communicates what is happening with the behavior that may not be apparent otherwise. Behavior can change so slowly that you would not see it without putting it on a graph.

Dr. Borders: At this point, we have the definition, you have collected data, and you have graphed initial information. Now where is your data taking you? What is the function or the payoff for the student? There may be multiple functions for the behavior, but this is the time when you need to develop your “If-then” statement. I always recommend that you focus first on the function that the student most often uses that behavior for. For example, if the speech language pathologist comes in to pull Tommy out for speech and he hides under the desk, the payoff is that Tommy can delay or get out of going to speech class.

Form a Hypothesis

Dr. Bock: Once you have your hypothesis, the replacement behavior can be taught. However, the replacement behavior has to match the same communicative intent as the inappropriate behavior.

Let’s talk about Tommy. He hid under his desk to avoid going to speech class. A replacement behavior would be to request a five-minute break in a quiet area prior to transitioning to the speech class. This is not reinforcing the inappropriate behavior. Would you rather lose five minutes of speech or the whole speech session? You would reinforce him for choosing the five-minute break instead of crawling under the desk. Over time, you would decrease the amount of break time you would give before Tommy had to transition to speech.

Here are the questions you have to ask yourself when you are coming up with a replacement behavior. How much time does the behavior take? How hard it is to do? How easy is it for someone else to understand the intent, and how quick is the payoff? What is the easiest, fastest, and most effective consistent way to gather someone’s attention? For example, screaming will get someone’s attention more quickly than raising a hand.

Behavioral Intervention Plan

Dr. Borders: Once you have determined your hypothesis for why this behavior is happening and what the function is, we develop a behavior support plan or intervention plan. Through this plan, the team develops an action strategy that details the specific steps to teach the replacement behavior. This intervention plan will be included in the student’s IEP.

The purpose of doing the FBA is to gain a clear picture of what is maintaining the inappropriate behavior so that interventions can be effective and efficient. First, we identify a teachable replacement behavior that matches the function of the inappropriate behavior. If it does not match the function, it will not be used by the student. This may mean that you change current antecedents in the environment that cue that behavior, teach new or more socially appropriate behaviors, and identify highly reinforcing items. Keep in mind that the closer the intervention plan reflects the assessment findings, the more likely that intervention is to be successful.

Dr. Bock: Behavior support plans include a summary of the findings of the FBA, student strengths, a summary of all prior interventions, and positive behavioral supports.

First, there is a statement that includes a description about the behavior. It should include antecedents and setting events most often associated with the behavior, maintaining consequence and the perceived function or the purpose of why the child is exhibiting the behavior. This is a positive approach.

The student’s strengths and abilities are included so we can build off them. Unfortunately, when we are looking at a negative, inappropriate, or atypical behavior, sometimes that function is on the negative component. Let’s switch gears and find out what that child does well. You will need to include all previously used interventions so that the team has an idea of what has and has not worked in the past. And, of course, the plan includes the replacement behavior and how to teach this new behavior.

The behavior support plan should be carefully and thoughtfully developed. Step-by-step strategies that may be used to reduce the likelihood of the student engaging in the inappropriate behavior are specified. Reactions the team members may make to the behavior or the ways to respond to the student that will not reinforce the behavior are integrated. If restrictive interventions or crisis interventions are deemed necessary, the exact plan for implementation must be included. You also have to include a process for not engaging in restrictive or crisis interventions. Methods for evaluation and the measurement criteria, or the data points we discussed, must to be agreed on by the team members and must be included as well.

Goal of Intervention: Replacement Behavior

Dr. Borders: The final piece of the FBA and the key to the behavior intervention plan is the identification of these replacement behaviors that are going to be taught. As stated previously, the replacement behavior must be carefully considered to ensure that the student will see it as positive and as a good alternative to the inappropriate behavior that they have been using.

First, replacement behaviors need to be relevant. We might consider how successful students and peers behave in the environment and what they do under similar circumstances.

Second, replacement behavior must be more effective than the problem behavior. If the decision is between an inappropriate behavior that works well and a replacement behavior that does not, the student will always continue with the problem behavior.

Third, replacement behaviors must be at least as efficient as the problem behavior. If the replacement behavior works, but requires a good deal of effort or works more slowly than the problem behavior, the student is likely to return to the more efficient problem behavior. If it works, but it is harder to perform, the student will not do it.

Dr. Bock: Over time, you will need to revisit and review the FBA and the behavior support plan that you created. As a student progresses, they may meet many of the short and long-term goals the team and family have hoped for. New behaviors may emerge that the current interventions do not target. Revisiting the entire FBA process to understand new challenging behaviors may be warranted so that new interventions can be developed and implemented. Even if the behavior is no longer exhibited, I always recommend keeping the FBA and the behavior support plan in place. That way, if the behavior re-emerges, there is a plan and you are not starting over from scratch. It also reminds you what has been successful in the past.

Questions and Answers

If a team is unfamiliar with FBAs, who should initiate an FBA on the team?

I think the school psychologist can often help you. Your social worker is a great place to start also. They are going to have the child’s information and the parent information as well. In school environments, you may have a behavior interventionist. I want to warn you to never back out of the process. You are the teacher or you are the support person. You know a lot about the child, and your information is incredibly important.

When a child screams, and then mom says, “Ask me nicely,” and then the child does ask nicely to get something, what do you suggest as an appropriate replacement behavior?

You will have to implement an intervention and then fade. Initially, if mom says, “Ask nicely” by signing it or speaking it, what she may do instead is pause and then say, “Ask nicely.” That pause allows that child to process. The pause becomes a part of the behavioral intervention chain. Over time, mom might pair a hand gesture or point to a smile on her lips for nice smile to provide something else so she is not verbally or sign-prompting the child to do that. The pause time is important for the child because it makes them stop and realize that mom wants them to ask nicely. She should fade the verbal or signed prompt over time. Understand that signing and verbalizing are the hardest prompts to fade. You always want to try to add a gesture some type of a pause in that behavioral chain.

Should each discipline perform their own FBA, or should one team member own that FBA?

No, I would never recommend that each different party involved with a student and family have separate plans. What needs to happen with a child with complex learning needs, which often happens with children with dual diagnoses, is that all of the team members need to be brought into that table to develop one plan so they can all perform uniformly with that one child. We cannot look at each one of our disciplines separately.

The child has been escalating hitting behaviors in day care and the staff is responding inappropriately. Could you explain how to educate the staff?

If the child is hitting the staff, you will do it differently than if the child is hitting other children. I can sometimes observe for a few minutes and figure out that the child is either trying to gain attention or the child has not learned from the other students or teachers in the environment. For example, if the child has not learned something as simple as sharing, they will just take what they want.

To educate the staff, you have to come up with the function and say, “I think Johnny is doing this because he wants your attention.” And if he is, then I would say, “Let’s find a different way for Johnny to gain your attention.” Those are redirections. You will need an adult in somewhat close proximity to that child at all times when you are initiating an intervention. As the child reaches out to hit another child, if for attention, you would gently guide that child’s hand to your hand or your arm to touch base and to gain the adult’s attention. That would be a pure physical redirection on that. Then you will want to say, “Give that child your immediate attention.” You do not want to say, “In a minute, Johnny.” Then that intervention or redirection will not work. I think the best way to teach the staff is to model it with them.

Cite this content as:

Borders, C., & Bock, S.J. (2014, December). Core strategies for supporting children with deafness and autism spectrum disorder: part 1. AudiologyOnline, Article 13116. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com