Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live webinar. Download supplemental course materials.

Learning Outcomes

The learning outcomes for the presentation are to identify three advantages of using a combined otoacoustic emission (OAE) and automated auditory brainstem response (ABR) hearing screening approach, cite a clinical guideline that recommends the use of combined OAE and automated ABR hearing screening, and describe how OAEs and automated ABR techniques are used in well-baby nursery versus intensive care nursery or neonatal natal intensive care nursery (NICU).

Agenda

I will start with an introduction which will cover newborn hearing screening in general, and then I will focus more on the two techniques individually. I will give a historical overview and pay tribute to some of the people who got us where we are over a 40-year history. Then we will talk about the rationale for why we should combine OAEs and ABR for screening children, which will include a brief review of the literature. I want you to be able cite that evidence in the case that you need to uphold your position for such screening measures in your place of employment. It is very compelling. Then I will mention some of the clinical guidelines for implementation of this combined technique. At the end, I will provide a summary of our discussion today.

Hearing screening of newborn infants with OAEs and automated ABR is not the end-all or final goal for any audiologist; it is the very beginning. We sometimes get hung up on different parts of this process, whether it is identification which includes the screening, the diagnosis, or the intervention. The ultimate goal is better outcomes for patients, and screening is the very first part of this. I do not minimize the role of screening; a good screening strategy sets you up for a more accurate diagnosis and also contributes tremendously to earlier intervention.

Early Hearing Detection and Intervention

In the area of early hearing detection and intervention, which is called EHDI, there is a real concern. In the United States, close to 100% of all babies are being screened, but when you look the number of babies who do not pass the screen and should be seen for diagnostic testing and receive intervention, that number drops from 100% to in some states to around 30% to 40%. In other words, only 30% to 40% of the children who fail hearing screening end up getting the intervention they need. The outcome clearly is not being achieved.

If the majority of children are not getting these later services on time, then the outcome will always be suboptimal. A good hearing screening program, including OAEs and ABR, can have a domino effect on this sequence of events. Earlier intervention can be tied directly to a good screening program, which means a better outcome. Screening is a very important link in the intervention chain, and you can improve the rest of the process by screening in the most effective and efficient way.

It is important for all audiologists to realize that we are not interested in defining hearing thresholds at the outset. We start by finding which children might have a hearing loss, then we then we go on to define how much hearing loss some of these children have. However, that is not our goal. Hearing, in and of itself, is not the most important process that we are trying to affect. Hearing is essential for oral language, and language and writing is the primary mode of communication. Communication is essential for quality of life. In this complex world in which we live, without the ability to communicate effectively, you cannot survive, at least not economically. What we are doing is more than just finding kids with hearing loss; we are changing lives. We can have a huge impact on whether or not many citizens will be self-sufficient and able to provide for themselves and their family. Our efforts go far beyond finding a hearing loss.

History of Newborn Hearing Screening

The earliest work on newborn hearing screening goes back to the 1960s. Without a doubt, if you had to identify one person who made more of a contribution to newborn hearing screening than anyone else, it would be Marion Downs. I like to pay tribute to this remarkable woman. Her efforts of studying over 17,000 neonates in the late 1960s led to the very first Joint Committee on Infant Hearing in 1982, which she organized herself. That was about the time many of us were beginning to go to our directors of neonatology and say that we need to have an at-risk hearing screening program.

At-Risk Screening

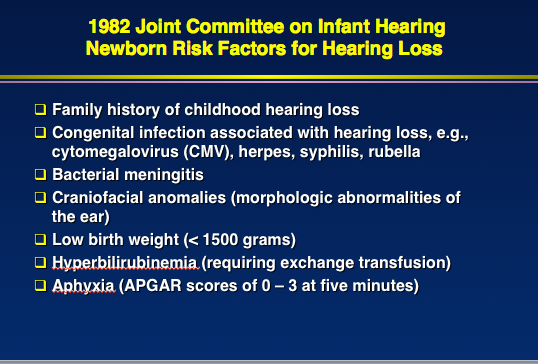

The risk factors are relatively small in number (Figure 1), but they were quite effective in identifying which children were most likely to have a hearing loss. There were some problems with the at-risk approach, but at least we were beginning the process of finding children who had a hearing loss that would impact speech and language development, communication, and quality of life.

Figure 1. List of newborn risk factors for hearing loss from the 1982 Joint Committee on Infant Hearing.

Universal Newborn Hearing Screening

People started to talk seriously about universal hearing screening in the late 1990s. Harrison and Rousch (1996) did a study of children who had hearing loss, including exactly when somebody suspected they had the hearing loss, when the diagnosis took place, when they received a hearing aid, and when formal aural rehabilitation or audiological rehabilitation started. The conclusion of their study was that it was always too late.

Even with no risk factors and a severe to profound hearing loss, it was at least a year before the children were diagnosed. In some cases, it was more than two to three years before intervention took place. Clearly, this was a major delay. Even then in the 1990s, we knew it was not good for a child to be walking around with a hearing loss for years before intervention took place. “Early intervention” was not defined at this time, but we did know that “years” was too long.

Jerry Northern and Deborah Hayes (1994) analyzed data from around the country at the time when people were convinced that the at-risk approach was failing to identify up to half of all the babies. There are roughly 23,000 to 25,000 babies born with a hearing loss in the United States every year, and almost half of them were healthy at birth and had no risk factors. You can always count on about 10% of any baby population as having some risk factors, but the other 90% do not. While four million babies born every year sounds like a big number, consider larger populous countries. For instance, between 24,000,000 and 25,000,000 babies are born in India every year. When you start doing the math, you can predict that a huge number of babies in India or China have hearing loss which is going undetected. These children are not being identified until it is much too late. We cannot identify children with hearing loss without universal screening. We might start with an at-risk program, but we have to transition as quickly as possible to a universal hearing screening program.

A turning point for newborn hearing screening in the United States came in March of 1993, when the National Institutes of Health (NIH) organized a consensus conference on this topic. The goal was to develop position statements on newborn hearing screening and to make a decision as to how we should go about identifying children. Toward the end of the meeting, all major news media were there. As a result of this conference, this group said we need to be identifying all children and that they endorsed universal newborn hearing screening based on evidence and rationale for that.

At the same time in the mid-1990s, the Joint Committee expanded their position statement and also endorsed newborn hearing screening of all babies using one of two techniques: ABR and OAEs. After the NIH consensus conference, we realized that we needed more research to answer some fundamental questions. Two of those were, “How early is early intervention?” and, “Does early intervention help and is it really necessary?” Believe it or not, there was no systematic study in 1993 to prove that early intervention helped. It was all anecdotal evidence, case reports, and people’s clinical observations.

Christina Yoshinaga-Itano, a good friend and colleague of Marion Downs who worked with her at University of Colorado, took this challenge on. She designed a study and published the results in 1998. This study pushed forward universal newborn hearing screening, not just in the United States, but around the world. She found that if you identify these children with hearing loss in the neonatal area, an intervention begins by six months with hearing aids and rehabilitation.

It does not take much rehabilitation when you find a child with a hearing loss and intervene by six months; you let nature take over. Most children do not need to be taught to speak. When they are immersed in language, they acquire language. It is a unique ability to human beings. Before six months of age was then defined as “early intervention.” Beyond six months, she found that the impact of hearing loss on speech and language was greater. She also found that any degree of hearing loss still had an impact on speech and language. However, with intervention, language, speech, and communication can be normal.

By 1999, the American Academy of Pediatrics had seen enough evidence to endorse newborn hearing screening. This meant that universal newborn hearing screening was going to take place everywhere in the United States, because pediatricians are the gatekeepers for infant healthcare.

Then, national and state legislation was passed starting in 1999. By 2000, most states had laws in support of newborn hearing screening of all babies. Then the movement began to go international. Since then, many countries around the world have instituted universal newborn hearing screening, and efforts along this line are underway in many developing countries.

Rationale for Combined OAE and Automated ABR Approach

So why not perform one or the other, as was the earliest recommendation by the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing? Either one will work, but I am going to take the position that you need to have instrumentation that will allow for both OAEs and automated ABR. They are better used together in many situations than alone.

ABR

The ABR was discovered over 40 years ago by Jewett and Williston (1971) and revolutionized all of audiology. Suddenly, we were able to evaluate infants and young children just as well as adults. If you had a child who was quiet, lying still, or even sleeping, it was possible to document their hearing status. The neat thing about ABR that was immediately recognized as perfect for a clinical tool was that everyone’s ABR looks the same. All normal ABRs essentially look the same. When the ABR is absent or deviates from a consistent, normal pattern, you know there is a problem. Now we can utilize toneburst stimuli, click stimuli, and speech stimuli. Recording an ABR is much more sophisticated now than it was 40 years ago, but the basic principle is the same. This is a wonderful tool for early detection and diagnosis of hearing loss in infants.

Robert Galambos established the validity of ABR as a pediatric tool for hearing assessment in his classic paper with Hecox in 1974. He proved that you could go into the nursery or audiology clinic and evaluate the hearing of any child using ABR. He published two other studies with colleagues in 1975 and 1979. He was no stranger to the ABR as he was Don Jewett’s mentor.

I was involved in the clinical effort of newborn hearing screening at Baylor. When Jim Jerger heard about the Galambos studies, he immediately said we need to set up our equipment to do ABRs. We started to do them in the audiology clinic and in the day surgery area when children needed to be sedated. This is a long and proud tradition.

As time went on, we began to do some studies of automated ABR. Without automation, universal screening is not possible. Audiologists alone cannot screen those four million babies born in the United States. We needed automation that would allow other people to do the screening. The parameters that we used to record ABR underwent study and modification, and now we have a very good test protocol for automated ABR in infants, which reduces the failure rate to the lowest level, but also assures us that we will detect all children with any significant hearing loss.

One of the big breakthroughs was the insert earphone in the mid-1980s. Insert earphones alone greatly reduced the failure rate, and they are still a very good transducer to use in pediatric ABR.

Automated ABR

One of the earliest studies on automated ABR was a multi-site study (Stewart, Mehl, Hall, Thomson, Carroll, & Hamlett, 2000). We found that the screening could be done any time after birth. This is one of the big advantages of ABR over OAE. This is why I think you always need to have both technologies. If you are screening a baby who was born within the previous 24 hours, use automated ABR. The failure rate is just as low with ABR as it will be two or three days later. With OAEs, however, the failure rate is very high within the first 24 hours.

In a study with more than 11,000 subjects, the failure rates were adequately low and met the American Academy of Pediatrics’ benchmarks. Our failure rate of 2% in this study was well under the 4% cutoff for the upper failure limit or benchmark for any screening program. We do not want to fail any more than 4%. We also found that our false positive results - how many babies failed who really should have passed - was also much lower than the benchmarks. Automated ABR works.

I am not promoting any particular company or device, but Figure 2 shows the Maico MB-11. It utilizes a one-piece device which includes both the earphone and the electrodes. It uses a very effective form of stimuli which is chirp. With this system, it is possible to perform an ABR within 15 to 30 seconds and pass an ear. Although ABR technology has been around for 40 years, it still continues to get better and better.

Figure 2. Macio MB-11 one-piece newborn hearing screener utilizing chirp stimuli.

Minimizing False-Positive Errors

One of the concerns, particularly in a country where there are millions of babies being born, is that we cannot be following millions of babies who end up with normal hearing. We have to minimize the false-positive rate. We have to fail the bare minimum of babies. One way of doing that is to combine ABR and OAE technology. Another strategy is to do a second screen with whatever technology you are using.

Clemens and Davis (2001) published a study showing that when babies were screened with automated ABR, 80% of the babies who failed passed when they were rescreened. Fewer than 4% of babies failed to begin with. At the second screening, the false-positives decreased from 3.9% to 0.8%.

How does that contribute to better outcome? If you only need to look for 0.8% of the babies who were screened, now you can put all your resources into bringing them back. At that rate, you are much more likely to get those children to come back. Almost all of those that fail on ABR screen have a hearing loss; that leads to earlier intervention and better outcomes.

OAE Technology

There is a long history of OAEs being used for newborn screening. In fact, OAEs were used for screening in the 1980s before they were used for anything else. Over the years, automation has come to OAE devices, and screening early on with transient OAEs has given way to screening with distortion product OAEs. The technology has improved. The devices have gotten smaller. The probes have gotten better, and the software for processing the OAEs in background noise has also improved.

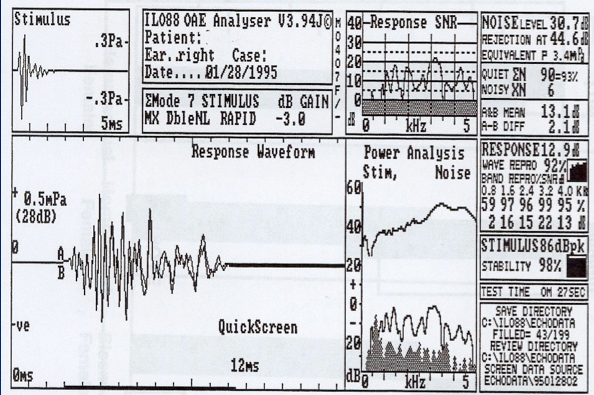

The first commercially available device in the U.S. was called the ILO88, introduced in 1988. Figure 3 shows the OAE waveform on this system. The stimulus is shown on the middle of the screen, and the OAE spectrum (white) rising above the background noise (gray) is shown on the right side. If you look at the signal-to-noise ratio, which is the size of the transient OAE compared to background noise, it was quite large. Anytime you have a signal-to-noise ratio or OAE-to-noise ratio of 6 dB or greater, it is a pass. The reproducibility (or correlation of the two waveforms) was almost 100% in this case. This is a pass by anyone's criteria.

Figure 3. TEOAE response screen from the Otodynamics ILO88 system.

OAE Validation

One study about OAE technology was done by a well-known pediatrician, Betty Vohr, and her colleagues (1998). She showed that it was possible to use OAEs as a primary screening tool, and the failure rates and over-refer rates (false-positive rates) were adequately low. Using a universal screening resulted in an average age of intervention that was within the first six months after birth. Over the years, hundreds of papers have described distortion product OAE screening techniques. Now there are number of DPOAE devices, dedicated to newborn hearing screening.

Review of Literature on Combine OAE and ABR Screening

When we are done with this section, you will say you had always thought you could get by with one or the other of these technologies, but now you are convinced that in a large percentage of babies, it is better to have both technologies available and utilize them in some babies.

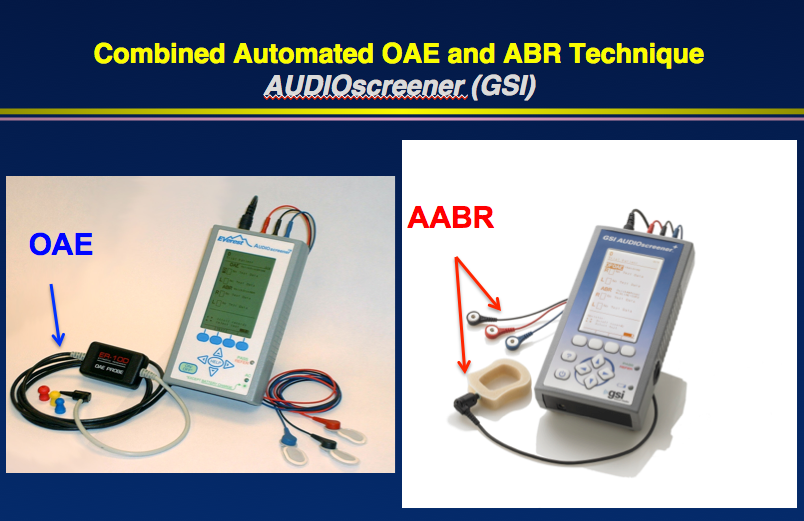

In 2004, I published a paper with Steven Smith and Gerry Popelka on combining these two technologies in the Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. Gerry Popelka developed a device called the AUDIOscreener, now marketed by GSI (Figure 4). This device included both OAE and ABR capability.

Figure 4. AUDIOscreener device with OAE and automated ABR technology.

This device has a probe which allows you to record OAEs. I have used this device in Head Start screenings and other OAE screenings. The same device also allows you to plug in earphones and a special headset with electrodes so that now you can perform the automated ABR. You can start either with ABR or OAEs and go to the other technology instantly just by pressing a button.

Our study in 2004 included 600 ears. We screened all of the babies with both technologies. Then we followed those children who had a refer result on either screen. The advantage of using both OAE and ABR is you can determine not only that the child did not pass the screening, but why they did not pass. This is a mini version of the crosscheck principle. OAEs and ABR are independent, as the mechanisms they examine are different. OAEs record sound produced by the outer hair cell activity in the ear canal, and the ABR records a neurophysiological response from the brain in response to sound.

When you take two independent tests like this and add them together, you have a much more powerful combination. If you have normal results for both OAE and ABR, you can be almost 100% certain that that child has no auditory problem affecting the ear or the auditory nerve. If you have abnormal results for the OAEs, but normal for the ABR, the most logical explanation is a problem with the external or middle ear. You can rule out external ear canal problems by looking in the ear. Most of these problems are middle ear or vernix affecting the OAEs in the ear canal, but not the ABR.

These are often problems that we can solve. This is the kind of child that should be passing a screening or at least will be effectively managed medically. When both OAEs and ABR are abnormal, that is almost always a sensory hearing loss affecting the outer hair cells. These are the children we want to detect. When both technologies give a refer result, you have to bring that child back in. This is where early intervention has helped, because you can convince parents and physicians that this child has a problem. The odds of that child having hearing loss are almost 100%.

When the OAEs are normal and the ABR is abnormal, that almost always suggests a neural or retrocochlear pathology. It should be considered that they might have auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder. The other possibility is inner hair cell, which is rare. We found in our study that not only was it more efficient and effective to screen with both technologies, it led to a quicker diagnosis of hearing loss and more effective intervention.

You could say each technique has its advantages and disadvantages, but when you put the two techniques together, you can say the disadvantages of one of these techniques will be overcome by the advantages of the other. You can differentiate between conductive, sensorineural, and sometimes mixed. You might say is this not something we should be doing at a screening. We definitely need to do it in diagnostic testing, but at the screening level, we are not documenting how much of a problem, we are just saying there is a greater likelihood that this child has a conductive problem. Rather than managing this child audiologically, they need to get to an otolaryngologist or pediatrician first.

In our study (2004), we found by combining these two technologies, you get what is almost impossible with a single technology, and that is the best of both worlds. There is almost always a trade-off with a single screening technique. When you increase sensitivity, you lower the specificity. You might be picking up all the babies with a hearing problem, but you are also picking up a lot of children who do not have the problem you are looking for. You can increase specificity, but decrease sensitivity. However, when you are using two techniques, you can get almost 100% sensitivity and specificity, which is a huge advantage.

Additional Studies

We are not the only ones to do this study. Another study (Johnson, White, Widen, Gravel, James, Kennalley, et al., 2005) did this two-stage screening mainly to find out how many babies pass the ABR but fail the OAE. Are we passing babies with automated ABR who should be detected? They found that there were some children who had very mild high-frequency permanent hearing loss who did pass automated ABR, but they failed the OAE. That is another good reason for using both techniques.

Tobe et al. (2013) in China argued that both OAE and ABR are a good idea. Of course, China has somewhere between 20 and 22 million babies born every year. Another study by Kumar et al. (2015) out of India agrees that OAE and ABR together is the best approach for hearing screening, particularly of large numbers of babies.

Another recent finding shows that the failure rate for distortion product OAEs was relatively high (Xu & Li, 2005). If that was the only measure you took, you would be failing almost 15% of babies. However, if you start with OAE screening, which goes very quickly, and 15% of them fail, then use ABR, which cuts the failure rate down to 4.5%. That is one strategy used in well-baby nurseries.

Recent Findings

You will see in a moment that that is not the strategy we would use in the intensive care nursery. I did a study at University of Pretoria with student Michelle VanDyke and my colleague, De Wet Swanepoel (2015). We studied the outcomes with OAE and automated ABR in South Africa.

The first screening was done in the first 48 hours after birth. For the OAE screening, we used transient OAEs with the AUDIOscreener. For the ABR screening, we used the Maico MB-11. These were the available systems, but you could use any combination of OAE and ABR equipment. We included 150 babies, for 300 ears.

The differences in outcomes of pass/refer rates of OAE alone and ABR alone occurred for what time frame in which the screening took place. In the hospital, if someone gives you the choice and asks when you would like to have your newborn screened, my first response would be, “When is my baby to be discharged?” If they say the baby will be there for two days (48 hours), say that you would like them screened in the last 10 to 12 hours before discharge. Screening 10 minutes before leaving can be stressful because people are watching, wondering when you are going to be done with the screen. Do not time it too closely.

If they say healthy babies are discharged within the first 24 hours, then I would use ABR for certain. At under 24 hours, the failure rate is greater for both technologies than it is later, but the failure rate is far greater for OAEs at under 24 hours old than ABR.

There are still quite a few failures for OAEs and ABRs at 24-48 hours of age, but these are far less for ABR (36% OAE refer rate vs. 16% ABR refer rate). At greater than 48 hours, the OAE refer rate drops to 26%, but there are almost no failures with automated ABR at only 3%. If you have a nursery and some babies are being discharged earlier than others, use automated ABR on those babies and use transient OAEs on the babies being discharged later.

OAE and AABR Screening Techniques: 2007 Joint Committee on Infant Hearing Recommendations

The Joint Committee has developed evidence-based guidelines that focus on how we identify and diagnose hearing loss in infants and young children.

Well-Baby Nursery

The most recent document from 2007 clearly and unequivocally recommends, for the first time, screening babies in the well-baby nursery differently than those in the intensive care nursery. Well-baby nurseries can screen with either OAEs or ABR. However, in many cases, you will start with the OAEs. There is no reason why you cannot use OAEs in the well-baby nursery. If they fail, you can immediately screen with automated ABR.

NICU

In the intensive care nursery, using OAEs first is not the standard of care. That would be going against the Joint Committee recommendations. Because people recognize that most babies with auditory neuropathy will be found in the NICU, automated ABR is recommended for all babies there. I am not saying that most babies in the intensive care nursery have auditory neuropathy, but that is where most of the auditory neuropathy cases are going to be found.

In fact, people are now showing that the greater the hearing loss, the more likely the child has auditory neuropathy. Auditory neuropathy in the general hearing-impaired pediatric population may be around 5%, but when you get into the severe to profound categories, it rises to 15%. You cannot take a chance and be screening all the babies in the NICU with OAEs. You would be failing every baby with auditory neuropathy.

In the NICU, start with an automated ABR (AABR) screening. If they pass, you are done. You do not follow them unless they are at risk for progressive or delayed-onset hearing loss. If the AABR screening results in a "refer", then do OAEs right away. If they refer for OAEs also, then it is likely a sensory hearing loss. If they pass the OAEs when they have already failed the automated ABR, we now start thinking about neural loss.

Summary

I have presented you with plenty of evidence indicating that we should routinely consider OAE and automated ABR for newborn hearing screening. There are different ways of combining these two technologies.

In the well-baby nursery, we can start with OAEs. If they pass, let them go, but if they fail, immediately screen with automated ABR. If they pass the ABR, then we can consider it a pass. That will result in the lowest possible failure rate, meaning that only the babies we really need to follow are being identified. It is certainly appropriate to use both OAE and ABR in all babies, and it would only add an extra two or three minutes, particularly if you have a device which allows you to perform both techniques.

If you are in the intensive care nursery, there is no question that automated ABR must be done first. If you are screening babies in the well-baby nursery within 24 to 48 hours after birth, you might consider using automated ABR. Using this combined technology allows us to fail fewer newborns. This allows efficient screening techniques, and when the child fails, we will know why they are failing and we will get them to the diagnostic process much faster, which will lead to quicker intervention and better outcomes.

In the last 30 years, we have gone from where only at-risk children were being screened in certain settings to a point where universal hearing screening is the law of the land in the United States and other countries as well. Combining OAEs and ABR in screening will assure that you are using state-of-the-art strategies, standard of care, and following clinical guidelines for hearing screening.

Questions and Answers

Do you recommend DPOAE versus TEOAE for the screening?

For a baby born where no one suspects hearing loss and as a routine universal newborn hearing screening, either technology will work. There are some distinct advantages to the distortion product OAE in certain cases. If the child is getting ototoxic drugs, then I would definitely opt for the DPOAE, because you can manipulate the screening protocol and focus on higher frequencies where the ototoxicity is likely to present first.

One problem we ran into when we were using the transient OAEs in a study back in the early ‘90s was getting a quiet test environment. You cannot tell all the babies in the nursery to stop screaming. You do not have much choice with transients when it comes to noise. You cannot work your way around it with the stimuli.

With DPOAEs in a noisy setting, you always have the option of limiting your screening frequencies to maybe 2000 Hz and above, or even 4000 Hz and above where there is no background noise. That has been a backup I have used. The rationale for that is that almost all hearing loss in infants is going to affect the high-frequencies. If it affects all the frequencies, certainly you will still fail them if you are screening the highs.

If you are using OAEs in a diagnostic capacity for a child who is coming back from a screening or with a suspicion of a hearing loss, both transients and distortion products are produced in very different ways; the mechanisms are different. I would recommend using both TEOAEs and DPOAEs in diagnostic settings with children, but for well-baby screening, either one is adequate.

What protocol would you recommend for those who fail the OAE but pass the automated ABR?

There are several ways of addressing that combination of failing OAEs abut passing automated ABR. The likely suspicion there is a problem in the ear canal. The first thing I would do is to look and see if there is any lotion-like substance on the probe tip. If so, that suggests that it is vernix. Put the probe in and out a few times. Clean the probe and you may very well pass the OAE.

If there is no evidence of vernix and you have an otoscope, take quick look. If the ear canals look clear, then we begin to suspect that it is middle ear. In that case, certainly you could use tympanometry. There are some nice devices on the market which allow you to go back and forth from OAE to tympanometry or wideband reflectance very quickly. Research in a number of good papers shows if you combine some middle ear measurement technique, like wideband reflectance or tympanometry, with the OAE, it is a much more effective strategy.

At the very least, if you do not have tympanometry, you want to follow that baby who failed the OAE and passed the automated ABR very quickly, because it may be a transient problem. I certainly would not get a parent excited or concerned about that. If the child were to come back to the clinic for a follow-up screening and have the same result (fail OAE, pass automated ABR), I definitely would go on and do tympanometry or some measure of middle ear function. That is the most likely explanation for that combination.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Newborn and Infant Hearing. (1999). Newborn and infant hearing loss: detection and intervention. Pediatrics, 103(2), 527–529.

Hecox, K. E., & Galambos, R. (1974). Brainstem auditory evoked responses in human infants and adults. Archives of Otolaryngology, 99.

Hall, J. W. III., Smith, S. D., & Popelka, G. R. (2004). Newborn hearing screening with combined otoacoustic emissions and auditory brainstem response. Journal of American Academy of Audiology, 15(6), 414-425.

Harrison, M., & Rousch, J. (1996). Age of suspicion, identification, and intervention for infants and young children with hearing loss: a national study. Ear and Hearing, 17(1), 55-62.

Jewett, D. L., & Williston, J. S. (1971). Auditory evoked far fields averaged from the scalp of humans. Brain, 94(4), 681-696.

Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. (2007). Year 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics, 120(4), 898-921. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2333.

Kumar, A., Shah, N., Patel, K. B., & Vishwakarma, R. (2015). Hearing screening in a tertiary care hospital in India. Journal of Clinical Diagnostic Research, 9(3), MC01-4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11640.5698

Northern, J., & Hayes, D. (1994). Universal screening for infant hearing impairment: necessary, beneficial, and justifiable. Audiology Today, 6(3), 10–13.

Schulman-Galambos, C., & Galambos, R. (1975). Brain stem evoked responses in premature infants. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 18(3), 456-465.

Schulman-Galambos, C., & Galambos, R. (1979). Brain stem evoked response audiometry in newborn hearing screening. Archives of Otolaryngology, 105(2), 86-90.

Stewart, D. L., Mehl, A., Hall, J. W. III, Thomason, V., Carroll, M., & Hamlett, J. (2000). Universal newborn hearing screening with automated auditory brainstem response: a multisite investigation. Journal of Perinatology, 20(8 Pt 2), S128-131.

Tobe, R. G., Mori, R., Xu, L., Han, D., & Shibuya, K. (2013). Cost-effectiveness analysis of a national neonatal hearing screening program in China: conditions for the scale-up. PLoS ONE 8(1), e51990. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051990

van Dyk, M., Swanepoel de., W., & Hall, J. W. III. (2015). Outcomes with OAE and AABR screening in the first 48 h - Implications for newborn hearing screening in developing countries. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 79(7), 1034-1040. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.04.02

Vohr, B. R., Carty, L. M., Moore, P. E., & Letourneau, K. (1998). The Rhode Island Hearing Assessment Program: experience with statewide hearing screening (1993-1996). The Journal of Pediatrics, 133(3), 353-357.

Xu, Z., & Li, J. (2005). Performance of two hearing screening protocols in the NICU. B-ENT, 1(1), 11-15.

Yoshinaga-Itano, C., Sedey, A. L., Coulter, D. K. & Mehl, A. L. (1998). Language of early- and later-identified children with hearing loss. Pediatrics, 102(5), 1161-1171.

Cite this Content as:

Hall, J.W.,III. (2015, October). Combined OAE and AABR approach for newborn hearing screening. AudiologyOnline, Article 15543. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.