Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live seminar. Download supplemental course materials.

APD Course Series

Today I will begin with an introduction, not just to this particular lecture, but to the auditory processing disorders webinar series on AudiologyOnline. Then we will talk about some definitions of auditory processing disorders (APD) and risk factors for APD, both for children and adults, as well as disorders co-existing with APD. Throughout those topics, I am going to be citing the research literature, which is growing exponentially.

This is the first of a series of four webinars on APD on AudiologyOnline. I will be giving last course in this series as well. It will focus on evidence-based assessment and intervention strategies and techniques. As guest editor of this series, I invited two other presenters who are both up and coming researchers in this area. Jeff Weihing is at the University of Louisville. I first met Jeff at UConn when I was visiting there and was very impressed with him. He is now a faculty member at the University of Louisville, and he is very productive in his research, both with Frank Musiek and now independently. He is going to talk about one of the oldest and most well-respected types of tests in the APD test battery, and that is dichotic listening tests - here is a link to his course. Any APD test battery must have at least one or two dichotic tests, and it has also led to a very interesting and effective treatment program for APD.

The other presenter in this series is Wayne Wilson from the University of Queensland in Australia. Wayne obtained his PhD in South Africa. He asked me to be on his dissertation committee because he was studying auditory brainstem response in patients with severe head injuries, and I have done a lot of work in that area. That was in the early 1990s, before I had ever met him. Like many people from South Africa, he is living now in Australia. Over the years, Wayne has carved out several areas of expertise; one of them is APD. He is going to give a unique perspective on APD - here is a link to his course. I invite you to take the rest of the webinars in this series, and I think you will find it to be an informative package of courses.

We cannot do justice to the topic of APD in one hour. Even in this series, we are only brushing the surface. In fact, we could carve out any area of APD and easily spend four or five sessions on it alone. You can get more timely information on APD in a new book series called the Handbook of Central Auditory Processing Disorders (Musiek & Chermak, 2013a; 2013b); this is a second edition of the book, which has been expanded. I have no financial interest in this whatsoever. Volume 1 is Auditory Neuroscience and Diagnoses. There is a lot of practical information, but it also covers a lot of basic information that you need to have. There are many well-known people in this area who contributed to the book, such as Frank Musiek, Gail Chermak, Nina Kraus, Teri Bellis, Jeff Weihing, and Sam Atcherson. The second volume of the book has 23 chapters as well and is called Comprehensive Intervention, which covers intervention, rationale and the science behind APD.

Not only do we know a lot about the underlying mechanisms and processes that lead to APD, but we also have good test batteries. They are going to get better over the years, but in 2014, we can evaluate auditory processing disorders and distinguish them from the most common co-existing disorders. Most importantly, I am going to emphasize the intervention. Even if you can diagnose a problem, you have not done much if you cannot intervene effectively.

Our final measure of how well we are doing is the outcome of the patient. If you cannot help children and adults with APD be more effective communicators, to be be more successful in school and better readers, or to keep their jobs and communicate as much as they need to in any given situation, then you have not done much. This second volume of the Handbook of Central Auditory Processing Disorders (Musiek & Chermak, 2013a; 2013b) hits upon all the treatment options available right now. I strongly recommend it to you.

History

Let’s go back to Northwestern University in 1954. At that time, Helmer Myklebust, who was a psychologist, was on the faculty. Not only was he a pioneer in APD assessment, but he also was a founder of the field of learning disabilities. He was a brilliant man who became interested in hearing in his first job as a psychologist at the Tennessee School for the Deaf. He stayed interested in auditory function throughout his life. I recently was asked and honored to write a preface for a new textbook that Jim Jerger is writing. The reason I mention this is that he talks in his book about Myklebust and how he was a student at Northwestern University at this same time.

Jerger took courses from Myklebust, and he went to the clinic. That was when Jim Jerger first realized that there was more to hearing than the audiogram. They would have children come to this clinic, which was kind of an auditory learning disabilities clinic, and they would observe normal audiograms. The parents would describe how they were not doing well in background noise, specifically, and that things were not going well in school. Even then, they realized that there were problems in the brain affecting hearing. Their methods of assessment were relatively limited, but the recognition of auditory processing disorders dates back to the early 1950s. Jim Jerger was so impressed that he ended up devoting much of his career to the evaluation of the APD, and he has passed that on to people like me and many of his colleagues around the world. Remember Helmer Myklebust when it comes to how APD got started. He was not the only person, but his work was certainly very important.

Some people claim there is still much debate about whether APD exists and that there is no consistent way to evaluate to them and certainly no way to treat them. That is just not true. That may have been true back in the1960s and 1970s to some extent, although I would likely have disagreed even then. We are going to spend a lot of time today talking about the evidence that makes me so confident to say that auditory processing disorders are real. They have a foundation in the auditory system that can be documented electrophysiologically with functional imaging and behavioral tests, and they can be diagnosed and managed effectively.

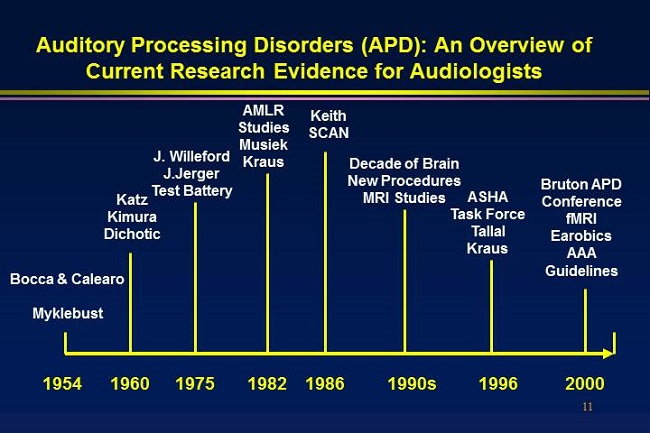

Let’s look at a timeline of research evidence for APD (Figure 1). Myklebust’s first APD study was in 1954. Interestingly, this was also the same year that three Italian otolaryngologists filtered out the high frequencies in some words and showed that patients with temporal lobe lesions in the auditory area could not repeat these words at all, whereas people with normal brains and normal hearing had no problem repeating these low-pass filtered words. Then, Jack Katz and Doreen Kimura developed clinical dichotic tests in the 1960s, which got the field moving. Theoretically, even in the 1960s as an audiologist, you could evaluate APD with a fairly sensitive test that we are still using today.

Figure 1. Timeline overview of current research evidence for audiologists.

Jack Willeford, who is deceased, and Jim Jerger developed the first test battery for APD back in the 1970s. They validated these tests and their sensitivity and specificity by finding patients at Baylor College of Medicine who had diagnosed brain abnormalities. They had cysts, strokes, tumors, abscesses, and various types of arterial malformations, and Willeford and Jerger showed that the tests that they were using then, many of which we still use, were truly sensitive to these problems in the central nervous system.

Bob Keith came along in the 1970s and was publishing books, but by the early to mid-1980s, he was developing tests, including a group of tests called the SCAN (Keith, 1994). It is a screening test battery, and he has done so much work to promote and document APD.

In the 1990s, APD testing took off. I was providing APD services throughout the ‘90s, and I distinctly remember many skeptics, including people that I was working with at Vanderbilt University at that time. As the ‘90s progressed, the research on fMRI, brain plasticity and neural science in general exploded. It was called the Decade of the Brain. It was all started by George H. W. Bush and Congress. They declared that we needed to know more about the brain and the central nervous system. We are still benefitting from that emphasis. Much of what I will be talking about today and the evidence underlying APD was first introduced back in the 1990s. By the mid to late 1990s, the American Speech-Language Hearing Association (ASHA) and other groups were beginning to develop criteria for diagnosing APD, including respectable definitions and strategies for management. Paula Tallal and Nina Kraus both showed electrophysiologically and behaviorally that APD did exist and it could be treated quickly with the right intervention. Since 2000, there have been numerous conferences, research efforts, thousands of papers and studies to lead us to where we are today.

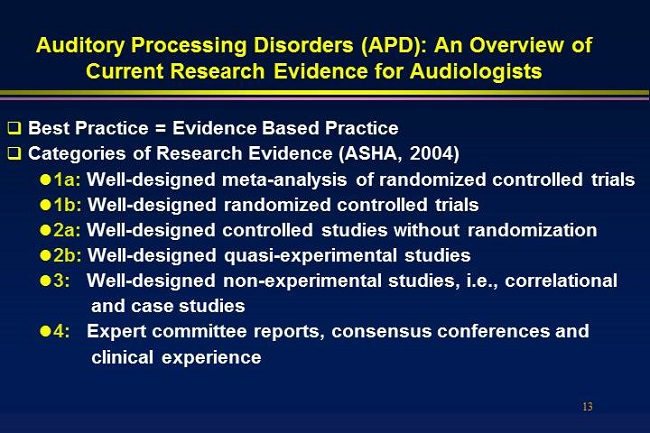

Not all evidence is created equal. Best practices are essentially evidence-based practice. Evidence-based practice, or EBP, is now a buzz word, but it is a reality. It is a process and rule that we live by. We always try to look to research evidence to support how we identify and manage children and adults with hearing loss. Most research articles and guidelines will reference the type of research they are citing. Some research is highly specific and collected with perfect experimental design and other research is more generic. There are different ways of categorizing research (Figure 2), but in this particular format, Category 4 is the weakest (ASHA, 2004). A lot of clinical experience seems to suggest that this works.

Figure 2. Categories of research evidence (ASHA, 2004).

Standard of care is based on, to a large extent, what people are doing - expert committee reports, consensus conferences, et cetera. Category 3 is a study, not highly experimental, but perhaps a case study or correlational study. It is well-designed, but it is not randomized and does not have a control group.

As we work our way up to categories 1a and 1b, we are looking at well-designed studies (Figure 2). Evidence from Category 1b is the perfect study, individually, where you have a couple of groups. This could be studying a screening technique, a diagnostic techniques or an intervention technique. It does not have to be solely intervention. But where there are randomized groups, there is a control group, and an experimental group, and everyone is blind as to who is receiving what. Those are the kinds of studies you want to use.

There is then a level of evidence even higher than that – Category 1a. Review of literature is quite easy to do with the Internet, so people can now look at all the randomized controlled studies available and do a meta-analysis. This looks at the best of the controlled studies. You are taking the very best and then looking at them all together. That gives you even more power in terms of your conclusions. Evidence is important, and the better the evidence, the more confident we can be about our clinical practice.

Definitions

Let’s quickly review some definitions. There are many definitions for APD. Jim Jerger (2009) once said, “APD means different things to different people (p. 10).” That is true. If you are talking about APD with a speech pathologist, they sometimes refer to linguistic processing, not auditory processing. Psychologists often talk about auditory forms of cognitive processing, and even among audiologists, different people have different definitions. That is not necessarily a problem, as long as there are certain salient characteristics of APD upon which we can all agree.

One definition, which came out of the Bruton conference that Jim Jerger organized in Dallas in 2000, says, “APD is broadly defined as a deficit in the processing of information that is specific to the auditory modality,” (Jerger & Musiek, 2000). We can talk for an hour about this co-concept of modalities and whether you can even have APD if there are other problems in other modalities. The answer is yes, and that issue is discussed at length in the Handbook of APD (Musiek & Chermak, 2013).

The concept of specificity is important. When a patient has problems with background sound or experiences distraction when there are other types of stimulation and they are not communicating effectively, that could be due to many factors, such as tension problems, language problems, emotional problems, cognitive deficits, or an auditory nervous system problem. We need to be able to sort that out and be able to say there may be other problems that this child or adult has, but auditory processing is one of them, and we are confident of that.

I view APD a little differently than some others, in that it can happen anywhere in the auditory system. You can have deficits in auditory processing in the cochlea or the auditory nerve, as well as the central nervous system. To distinguish what we are talking about, many people use the term central auditory processing or they put central in parentheses to emphasize that that is where most of the diagnostic and intervention efforts are focused. But certainly a patient, whether adult or child, with a peripheral auditory processing problem and a central component is going to have more problems than just one or the other. I have seen many patients who start out with a peripheral problem, and they do okay with a hearing aid or with some assistive help. However, as they age, they may not realize it, but they develop a central auditory problem and their communication problems become serious. This scenario can happen the other way around, where the central problem presents first and a hearing loss develops later in life.

The next definition is from an ASHA task force that produced a document in 2005. “Auditory processing is “the efficiency and effectiveness by which the CNS utilizes auditory information.” They talk about the efficiency and effectiveness in how the central nervous system utilizes auditory information. That is a very important concept that is part of the definition. You can have people who function adequately in ideal situations with no background noise, where the speaker is speaking slowly with low-level auditory information, lots of redundancy, and the listener will do just fine. However, when you put them in a real-world situation they cannot handle it. Efficiency and effectiveness are important components of an auditory processing disorder, or inefficiency and lack of effectiveness, I should say.

Another document is a set of clinical guidelines which were the result of the American Academy of Audiology (AAA; 2010) task force that was published, peer-reviewed, and evidence-based. It talks about APD not just being a pediatric problem. For example, we have many veterans who have suffered traumatic brain injuries in combat from major blast explosions and now have APD. Many adults experience this as part of a normal aging process. It is not just a pediatric problem.

One of the goals in evaluating APD often is to determine if this is a developmental problem, a neurodevelopmental problem or a true lesion, which is quite unusual. The same thing goes for adults. The clinical guidelines are certainly the best source of information on how to evaluate and intervene in children and adults. I also want to emphasize that APD is auditory specific. It is not a linguistic processing deficit; it is not a cognitive processing deficit, although those both might play a role. It is also not a form of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), although that, too, will be found in many patients with APD.

I was fortunate to be on the AAA task force with Frank Musiek, Teri Bellis, Gail Chermak, Jane Baran and a few others. If you want one document to guide your clinical practice, no matter where you live, this is a good starting point (AAA, 2010). You can download it from the Academy web site. It is very comprehensive and will bring you up to date on this topic. It provides evidence-based guidelines on how to evaluate it and intervene. It is more than just talking about APD.

Auditory processing is not just an auditory problem. I emphasize this when I lecture to speech pathologists or others. Auditory processing is the foundation of communication. It underlies phonological awareness, which is one of the most basic of the five reading skills. Children who are not able to recognize phonemes or speech sounds are not able to manipulate them, not able to link accurately the speech sounds to their representative graphemes or letters of the alphabet, and they cannot read well. They never will until that problem is addressed.

Auditory processing is directly linked to difficulties in auditorily distinguishing among speech sounds. Auditory processing is also fundamental to reading and spelling. This is a huge area in comprehension. Above comprehension, we could list things like academic success, quality of life, effective communication, and ability to compete in today’s world. Auditory processing is fundamental to communication in general. Most of what we learn up until grade two or three, and almost all of our critical day-to-day communication, involves auditory processing.

In children, there are many consequences of late APD identification. We have already mentioned quite a few of them, but APD is just as serious as a severe to profound peripheral hearing loss. In fact, it not only has academic implications and communicative implications, but as you will see, psychosocial problems also arise from APD. I have a couple of papers that I have published with former students on this. These patients with APD have such serious frustration and irritability, sometimes even clinical depression, that many of them should be seen by a clinical psychologist. Our research has shown that when the APD is effectively addressed, they do not have psychosocial problems anymore. It goes beyond just a hearing problem. It affects their whole life. If this problems is identified late, and by late I mean third or fourth grade or middle school, then the remediation is never as effective, lasts much longer in duration, and is more costly financially. Early identification is critical for APD, just as it is for peripheral hearing loss.

I am presuming that I am talking to audiologists, so I am not going to give you a lecture on central auditory system anatomy. Frank Musiek and Jane Baran (2006) have a wonderful book on auditory neuroanatomy. If you are at all interested in this topic or if you teach students, I strongly recommend it to you. I will emphasize that we do hear with our brain. The research from the 1990s onward has shown that a tremendous amount of auditory processing constantly takes place in the brainstem as well as the cortex. The other thing that is very important to recognize from the 1990s is neural plasticity. The brain can be changed. Just as the brain can be abnormally shaped by inadequate or inconsistent auditory stimulation, so can the brain be remediated or retrained by proper intervention. The research on that is paramount. I get into this concept and its relation to APD in my latest book (Hall, 2014). This book is geared toward undergraduate students, including people who are taking courses in speech pathology, who might actually be interested in audiology. We hear with our brainstem and cortex.

Decade of the Brain (1990s)

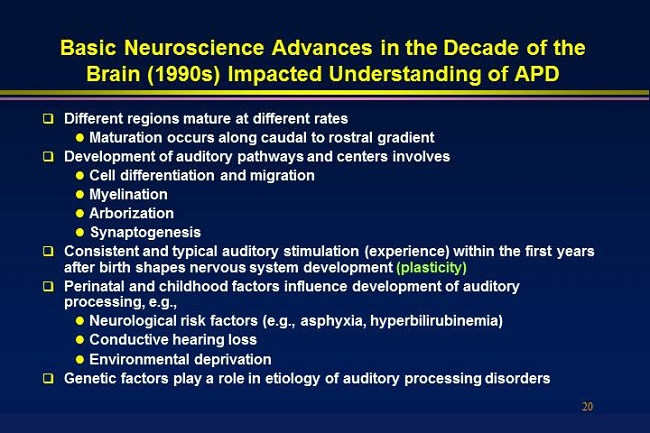

I have already emphasized the “Decade of the Brain” since the research from that decade and later underlies this whole course. We learned that there are many neurobiological aberrations or changes that can occur in children that will affect auditory processing. Many of these happen in infants and young children, but they can happen at any time. If there is some type of insult to the brain, such as a traumatic brain injury, that also can disrupt auditory processing. The good news is we can change it. With intense, appropriate and adequate intervention, we can change the brain. We can see dramatic changes in auditory processing within three to four weeks using some of these treatment programs, and almost always within a couple of months. I have shown in research with FM technology that just a single school year of using a personal, high-quality FM system gets most children to the point where they do not need to use it anymore (Johnston, John, Kreisman, Hall, & Crandell, 2009). The brain is changed. Neuroscience underlies everything we have talked about; a summary can be found in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Summary of neuroscience advances in the 1990s that impacted understanding of APD.

We know a lot about auditory processing for different reasons. One way was through auditory evoked responses. In the interest of time, I am going to quickly go over this. The cortical responses and the auditory brainstem response (ABR) have yielded tremendous information about how the brain processes sound. The nice thing about auditory evoked responses is we do not have to rely on behavioral tests that are subject to motivation factors, listening factors, cognitive factors, language confounds, and attention. We can get very pure results on auditory processing using auditory evoked responses. One of the big breakthroughs has been not just ABR, but speech-evoked ABR. On her Web site at Northwestern University (www.soc.northwestern.edu/brainvolts/), Nina Kraus has files you can download relating to this; you can watch videos that she has. It is phenomenal the research that Nina is doing. It not only involves auditory processing with speech, but also with music. Paul Kileny and colleagues at University of Michigan (2014) published an article demonstrating that even the click ABR with two clicks presented very closely together can reveal timing deficits in the brainstem that are vital to language and reading.

Nina Kraus has used her speech-evoked ABR to show that the brainstem is constantly processing speech, and that when there is intervention for these problems, such as Earobics, a very simple intervention strategy, the brainstem changes. The brainstem itself has properties of neuroplasticity, not just the cortex. The entire speech stimulus produces a brain response to speech. There is a neural representation of the speech. This can be done on people of all ages.

The cortex, the thalamus, the primary auditory cortex, and the pathways running from them are vital for communication. Many of the results we get from the middle latency response plus our behavioral tests arise from the primary auditory cortex. There is a large body of literature available. You can search PubMed, the National Library of Medicine, or National Institutes of Health. You can find the abstracts online and locate the author information. I sometimes e-mail authors and ask them for a copy of their article. I have been getting dozens of articles this way. The auditory cortex, both through fMRI and cortical evoked responses, is being studied in depth. We know what the primary auditory cortex does, and we also know that posterior to the primary auditory cortex is the planum temporale. Research is showing that there are definite abnormalities in the size of these structures and how they function in patients with reading and auditory processing disorders, and even language. The research is exploding. I did a Medline search on auditory processing reading, and I received over 800 articles. I did auditory processing reading and functional MRI and found 300 articles.

The cortical response is being used regularly in the research lab to document reading and auditory processing deficits, particularly in the N1 and the P2 parameters. In fact, Jim Jerger’s book to be released in the next six months is called Auditory Event Related Potentials to Words. It will be very useful and easy to read. We also use the P300 response. The P300 response is delayed in patients with APD compared to normal listeners. This is not new information. The late Bob Jirsa (1992), who was in Connecticut, was studying P300 in patients with APD more than 20 years ago. I have also done some research with almost 200 subjects showing that these late responses are very often abnormal in patients coming in for an APD assessment (Hall, 1995).

The mismatch negativity response (MMN), although not a clinical procedure, has produced dozens of studies showing abnormal auditory processing in patients with APD. The same abnormal auditory processing can be found in infants who are born of parents who cannot read or parents who have language impairment. A great article by Naatanen and colleagues (2012) is Mismatched negativity: A unique window to disturbed auditory processing in aging and different clinical conditions. He talks about reading in this article as well.

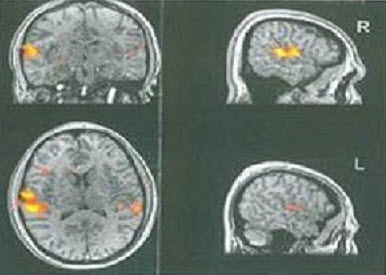

Functional MRI, which is abbreviated fMRI, is another tool that has been used to prove what regions of the brain are abnormally involved in auditory processing. There are well over 300 articles on this subject. Figure 4 shows an fMRI from one of my patients who had a very atypical right-ear deficit on all the dichotic tests. This boy was about 14 years old, struggling in school and failing. Because he had a right-ear deficit on every dichotic test, I kept thinking that it suggested that the left side of his brain may not be dominant for language as his auditory processing is taking place in the right side of the brain. His left ear scores were strong. His right ear scores were weak. Look at the left side of his brain on the fMRI (Figure 4). There is no activity there at all. All of his processing is taking place in the right hemisphere. This was just a simple clinical patient, but this is the kind of research that has exploded over recent years.

Figure 4. fMRI results from an 18-year old male APD patient with a right-ear dichotic deficit.

Risk Factors for APD in Children and Adults

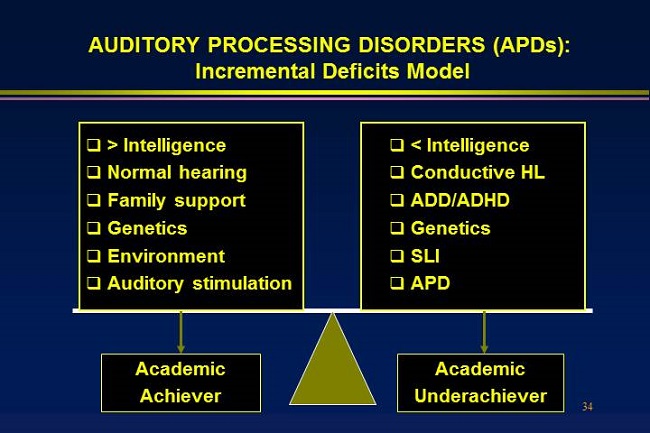

I developed a diagram of a scale that, on one side, shows the positive qualities to academic achievement, and on the other side of the scale, you see barriers to academic achievement, including APD (Figure 5). You will find children have different problems in different areas. You wonder what is really causing the academic underachievement. It is a combination of factors. There is a theory now called the multi-risk model for developmental learning/language problems, or APD, which means these problems co-exist, and they do interact. A child with APD is going to have more problems with reading or language than a child who has normal auditory processing. There is a huge amount of literature on this.

Figure 5. Incremental deficits model showing the factors that can contribute to academic success or academic underachievement.

There is no true, separate module for auditory function. The auditory system is closely connected to the reading and language system, and cognition underlies all of these tasks. This is one thing that has confused people over the years and made them think that we do not know if there really is an APD. There is, but it is closely linked to brain processing everywhere. Use today’s handout for a literature list or do your own search. You will find many relations between auditory processing, language, reading, attention, cognition, et cetera.

How do we find these children? What are the risk factors? If you find children who have had chronic otitis media in the preschool years, who had some type of insult to their brain as an infant, who are not doing well in school, or who have a family history of APD or hearing loss, there are genes now that are being discovered for auditory processing deficits. Family history is huge. Problems with tests that seem to be limited or primarily due to auditory stimuli probably hint at an APD. Even poor musical skills can underlie APD. That leads to a treatment option. The more a child is immersed in music from an early age, the more effective and efficient their auditory processing is. In fact, most children who are very musically inclined or at least exposed to music are the best readers. That research is being done by Nina Kraus and many others.

You can identify which adults should be evaluated through their medical history and audiological history. Almost anyone who is not doing well in communication, even though their audiogram suggests they should, or anyone who is not doing well with amplification, even though you have done all that can do to get a successful fit, should be considered for APD.

That leads to which disorders co-exist with APD. This is critical information because when we evaluate a patient for APD, we have to rule out or confirm these other disorders. If a child has ADHD or a language problem, it is going to affect how we go about evaluating them and how we interpret our test results. It is essentially an issue of differential diagnosis. Patients have a bunch of characteristics or signs or symptoms. Our goal is to determine whether the auditory system is responsible for some of them. These co-existing disorders co-exist because areas of the brain are all linked or connected. The primary auditory cortex is adjacent to the posterior auditory cortex, the planum temporale, which is adjacent to the angular gyrus where visual, sensory, and auditory information is all linked together. There are even pathways going from these areas to the frontal lobe. It is very important to recognize that APD is more than likely going to be associated with other disorders.

Co-existing Disorders

There is an obvious link between peripheral hearing and central hearing. Peripheral problems can lead to central problems, and central problems can result in even more deficits in peripheral problems. These disorders also include specific language impairment (SLI), reading and other learning disabilities, ADHD, and motion problems; all of these can co-exist with auditory processing. Dementia is a huge co-existing factor in adults. More literature now suggests that hearing loss in an older adult has a direct impact on cognition, and the more we effectively treat the hearing problems, including APD, the fewer cognitive problems the patient experiences. Any time you have a patient who is at risk for dementia, any cognitive deficit, or traumatic brain injury, or any patient who has a hearing loss and problems with communicating that exceed what you would expect from that hearing loss, you have to think about APD.

Summary

I hope at this point you feel that the research and evidence in support of APD identification, diagnosis, and intervention is growing dramatically and is rock solid. I encourage you to do a Medline/PubMed search (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/). You can keep up to date on everything. You can request these articles and read them just like someone in a medical center or university. As I was wrapping up my preparation of this, I typed in auditory processing disorder on PubMed. On January 28, 2014, there were 3,106 articles. The current research is extensive, and it is growing exponentially. I would say that of all the articles published in the literature on APD, 90% have likely occurred within the last 10 years.

That was a very superficial overview, but please refer back to your handout for references where you can locate additional information and articles.

Questions and Answers

I am a social worker. I frequently observe the psychosocial behavioral impact of APD on children and refer them for testing. My clinical interview often reveals early and ongoing otitis media.

Those are very perceptive and pertinent comments. The research was a little controversial for many years linking chronic otitis media in the preschool years with associated hearing loss, APD, language status and reading. Certainly, many children with middle ear problems and hearing loss in preschool years do not have these difficulties. There are a lot of variables that affect it. One is how quickly the problem is treated, and the other is the environment. Remember the scale diagram (Figure 5), the Incremental Deficits Model? One of the deficits on the right side was mild conductive hearing loss. The children who have one or more of those risk factors plus preschool history of middle ear disease are more likely to have APD. Also, if they come from a lower socioeconomic status, they are not going to have as much auditory stimulation, and that is just a research fact. If they do not have any musical experience or exposure, that will affect them in a negative way. The psychosocial problems are real.

When we did our research last year on this, the children we found who had APD had psychosocial deficits which were clinically relevant, but children who only had language impairment and no APD did not have the psychosocial component. We know that peripheral hearing loss affects psychosocial status. If you find a psychosocial difficulty and the child has had chronic middle ear problems, my advice would be to be as aggressive as possible in insisting on the diagnosis and intervention. The interventions can sometimes be relatively generic with a program like Earobics. That will never hurt, and it will help develop the auditory system and pre-reading skills. Music lessons are critical; the more auditory exposure the child has, the better. Remember also that FM technology would be perfect for someone with a mild residual hearing loss, perhaps 20 dbHL thresholds. Most people would not even call it a hearing loss, but that can influence a child’s classroom performance. If peripheral hearing deficits are due to a middle ear abnormality, sometimes the best option is an FM system.

When you discussed the brain dichotic deficit in the child’s fMRI, we lost your audio for a minute. Can you please repeat the information about the right-brain dichotic deficit?

Sure. This was a child who was referred by the mother. She was quite militant and pushy. This child had failed for years. He had horrible psychosocial problems. The mother was suing a school system for not identifying him. On every dichotic test I performed, his scores for the right ear showed 10%, 15% or 20%. On the left ear, where most children have deficits, his scores were close to 100%. He had a total reversal of the normal right-ear dominance. His left ear was dominant. She asked how we could verify what side of his brain was processing speech. I mentioned functional MRI and she took it upon herself to get him to a radiology center where they did this. It showed that he had a total reversal in his brain. That is a biological problem. He was born with it. I essentially testified in court that he had this APD without a doubt from day one. Had it been recognized when he was five or six, he could have had effective intervention that would have helped him.

Do you recommend FM systems to all children with APD?

That is a great question. I tend to be very result-focused when it comes to prescribing or recommending FM systems. My friend and colleague, the late Carl Crandell, had a different viewpoint. We would go to the schools, and he would tell them that every child needs an FM system, and I would debate this with him. I would agree, but it is not realistic. In terms of allocated resources, I think every child should benefit in the elementary school years from an FM system in the classroom. Nina Kraus’ work and our work clearly supports that, but when it comes to APD, my focus is usually on children who have problems in background noise, children who do not have perfectly normal hearing sensitivity, children who do not have normal otoacoustic emissions (OAEs), or children who I think need am improved acoustic signal. If that child is in a large class at an older school, yes I would definitely recommend an FM system. Nina Kraus’ research has shown that not only is school performance and psychosocial status improved, but so is reading (Hornickel, Zecker, Bradlow, & Kraus, 2012). If you must, err in the direction of getting the child a high-quality personal FM system. If there are limited resources, focus on the children who are most likely to benefit from it.

Can you cite any articles describing the genes associated with APD?

The New Handbook of Auditory Evoked Responses (Hall, 2006) does get into the genetic link. That has been known for many years for learning disabilities. There is at least a two-to-one ratio, sometimes three-to-one, of males to females in APD and learning disabilities and attention deficits. More recently, researchers have looked for a familial link. They find two adults who cannot read, are dyslexic or cannot read well and have always struggled. Very often, they end up marrying each other. They know there is a potential for genetic factor and they look at the MMN or fMRI in infants of those children before they have even had a chance to learn to read. These children have abnormal performance. That is how they have tracked it down. I cannot cite articles, but if you do a Medline search on genetics or hereditary auditory processing or hereditary language, you will find the articles. They are all recent within the last four or five years.

Can you comment on the recent indication that the Dichotic Digits Test (DDT) and Pitch Pattern Sequence (PPS) tests are the most sensitive in the APD battery?

First of all, auditory processing disorders are on a spectrum. They are heterogeneous. In other words, there are different types of auditory processes and children can have disordered processes in different areas. No one test is going to be sensitive to all children, so you want a battery of tests. Most tests tend to be sensitive, but not specific. The battery of tests gives you the sensitivity as well as the specificity. To properly manage children, you need to look at the results of a battery of tests. Some children only have problems with sequencing. I have run into children who have grossly abnormal scores for pitch pattern sequence or duration pattern sequence, but everything else is normal. Other children only have problems in background noise. Many other children have primarily temporal auditory processing deficits.

My research, as well as others, has shown that you are most likely to pick up on disordered children with a dichotic listening test if you only had one measure you could use. Dichotic listening involves auditory memory and temporal processing. The information has to get quickly up to both hemispheres. It does not involve speech in noise. It is closely related to reading performance. That is not a bad starting point. My research has shown that if you use a test like the Staggered Spondaic Word (SSW) test in kindergarten children, you can pick up the children who cannot learn to read. They are going to be closely tied to the children who also have language impairment. I would say to not only use a dichotic test, however, the dichotic tests seem to be very sensitive to most auditory processing deficits.

References

American Academy of Audiology (August 24, 2010). American Academy of Audiology clinical practice guidelines: Diagnosis, treatment and management of children and adults with central auditory processing disorder. Retrieved from https://www.audiology.org/resources/documentlibrary/Documents/CAPD Guidelines 8-2010.pdf

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2004). Evidence-based practice in communication disorders: An introduction [Technical Report]. Available from www.asha.org/policy. doi:10.1044/policy.TR2004-00001#sthash.sINGARqX.dpuf

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2005). (Central) auditory processing disorders [Technical Report]. Available from www.asha.org/policy. doi:10.1044/policy.TR2005-00043#sthash.K1aZasmE.dpuf

Hall, J. W., III. (2014). Introduction to Audiology Today. Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Hall, J. W., III (2006). New handbook of auditory evoked potentials. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Hornickel, J., Zecker, S. G., Bradlow, A. R., & Kraus, N. (2012). Assistive listening devices drive neuroplasticity in children with dyslexia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(41), 16731-16736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206628109.

Jerger, J. (2009). The concept of auditory processing disorder: A brief history. In A. Cacace & D. McFarland (Eds.), Controversies in central auditory processing disorder (pp. 1-14). San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Jerger, J., & Musiek, F. (2000). Report of the consensus conference on the diagnosis of auditory processing disorders in school-aged children. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 11(9), 467-474.

Johnston, K. N., John, A. B., Kreisman, N. V., Hall, J. W., III, & Crandell, C. C. (2009). Multiple benefits of personal FM system use by children with auditory processing disorder (APD). International Journal of Audiology, 48(6), 371-383. doi: 10.1080/14992020802687516.

Jirsa, R. E. (1992). The clinical utility of the P3 ERP in children with auditory processing disorders. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35, 903-912.

Keith, R. W. (1994). SCAN–A: A test for auditory processing disorders in adolescents and adults. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Musiek, F. E., & Baran, J. A. (2006). The auditory system: Anatomy, physiology, and clinical correlates. Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Musiek, F. E., & Chermak, G. D. (2013a). Handbook of central auditory processing disorder, volume I: Auditory neuroscience and diagnosis. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Musiek, F. E., & Chermak, G. D. (2013b). Handbook of central auditory processing disorder, volume II: Comprehensive intervention. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Myklebust, H. (1954). Auditory disorders in children: A manual for differential diagnosis. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton.

Naatanen, R., Kujala, T., Escera, C., Baldeweg, T., Kreegipuu, K., et al. (2012). The mismatch negativity response (MMN) -- A unique window to disturbed auditory processing in ageing and different clinical conditions. Clinical Neurophysiology, 123(3), 424-458. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.09.020.

Cite this content as:

Hall, J.W., III (2014, June). Auditory processing disorders: an overview of current research evidence for audiologists. AudiologyOnline, Article 12703. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com